History

The abbey was founded in 1179 by the bishop of Kraków Gedka, as a daughter of the Cistercian convent of Morimond in Burgundy. In 1249, Prince Bolesław the Chaste gave the monks ownership of the Bochnia salts and granted the privilege of mining metals, providing the abbey with high income and development opportunities. Unfortunately, eleven years later Wąchock was invaded by the Mongols, robbing and killing monks, as well as burning the monastery church. After the destruction of 1260, Bolesław the Chaste gave the abbey new goods and brought more Cistercians from Morimond, and around 1270 the bishop of Kraków Paweł from Przemankowo consecrated the rebuilt monastery church.

Probably in the fourteenth century, the monastery cloister was rebuilt and a separate building for the abbot was built outside the monastery buildings. At the end of the 15th century, abbot Jan Klecisz raised the gables of the church and covered it with a new roof, while in the 16th century minor changes were introduced by the abbots in the church’s interior, in the southern part of the east wing and in the abbot’s house, which was covered with sgrafitti.

In 1637 there was a dangerous fire, which significantly affected the later appearance of the abbey. During the reconstruction, the western wing in particular underwent a thorough transformation in the Baroque style, it was also decided to build the second floor over the entire enclosure, which required the unification of the height of the former vaults and led to the modernization of the dormitory in the eastern wing. The reconstruction works were interrupted in 1656 by the invasion of Transylvanian troops of George Rákóczi, because of which destructions were removed until 1695.

Another rebuilding of the church and monastery took place around 1750. After plastering the internal walls of the church, they were decorated with frescoes, and the chapel of Wincenty Kadłubek was added to the northern aisle. These were the last Baroque changes, because at the end of the 18th century the abbey crisis began, which from 1797 was only a prior. In 1819, a government commission dissolved it and the Cistercians were forced to leave the monastery, which was sealed and closed. The monks returned to Wąchock only in 1951. In the meantime, the monastery church began to function as a parish church.

Architecture

The Wąchock Abbey was located on the left bank of the Kamienna River, flowing on the northern and eastern sides of the monastery, in areas in the 12th century not yet inhabited and rich in natural resources (stones, beech and fir forests, iron ore). At that time those areas were wetlands, occupied by bogs with small clumps.

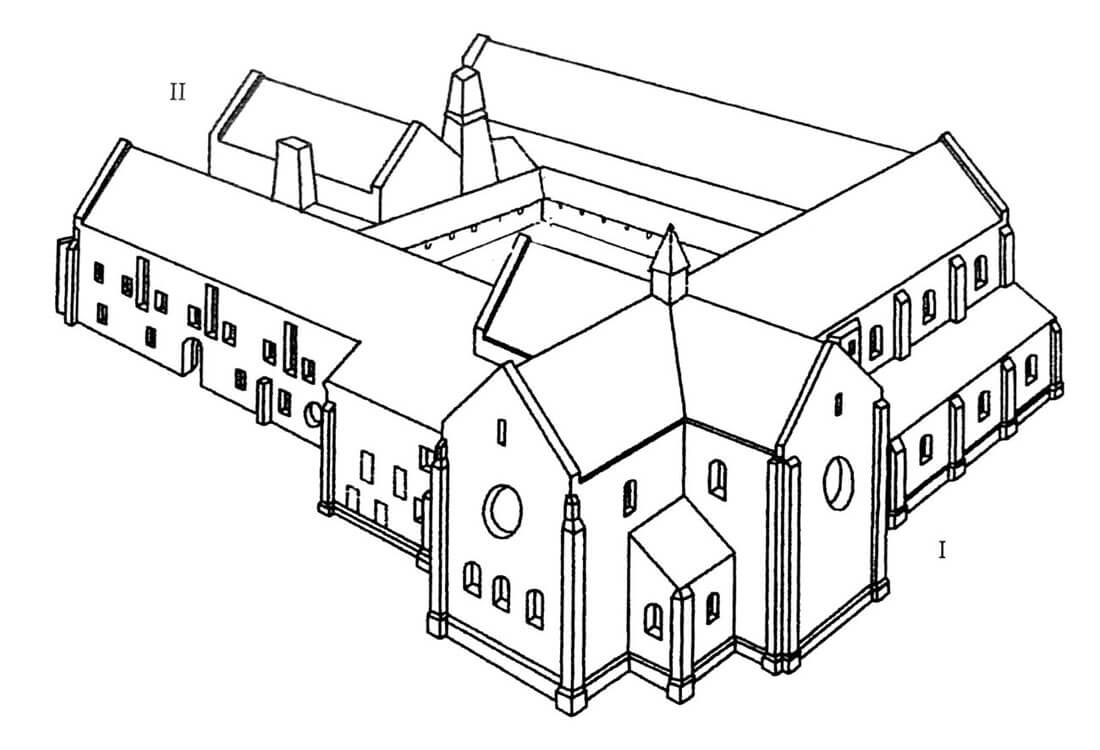

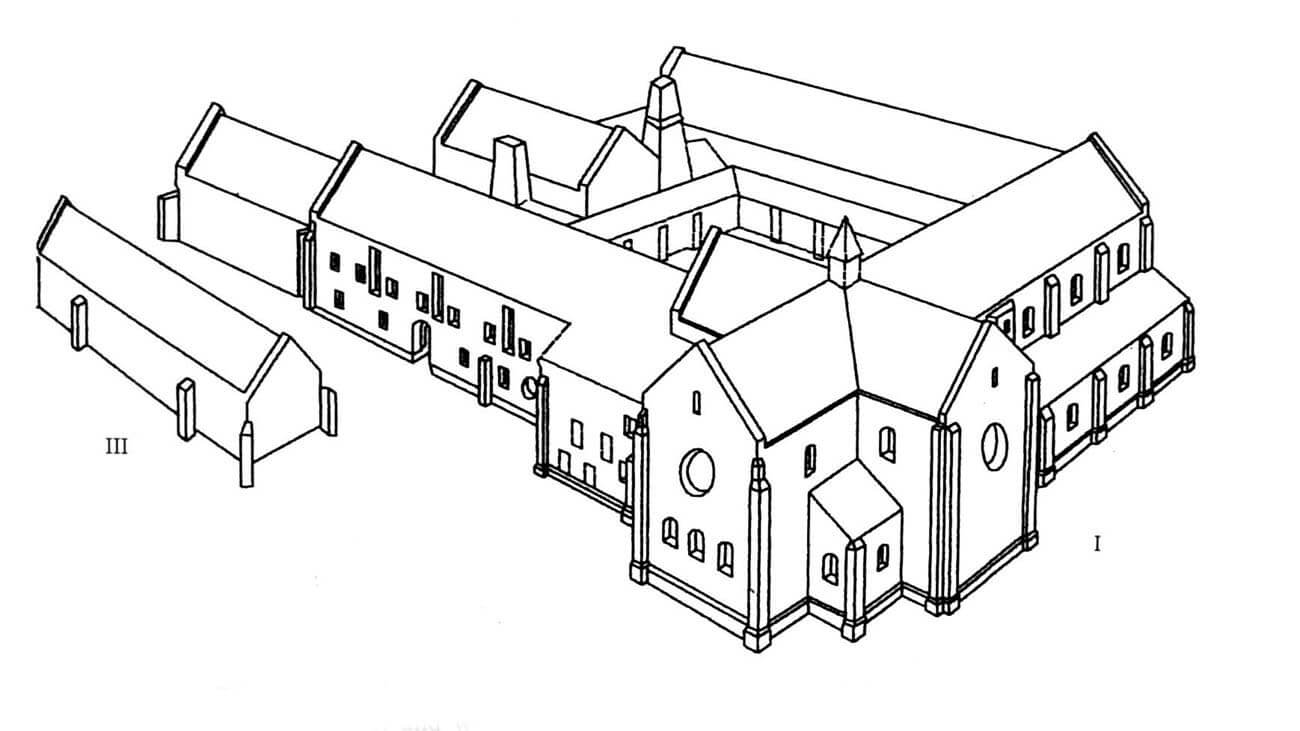

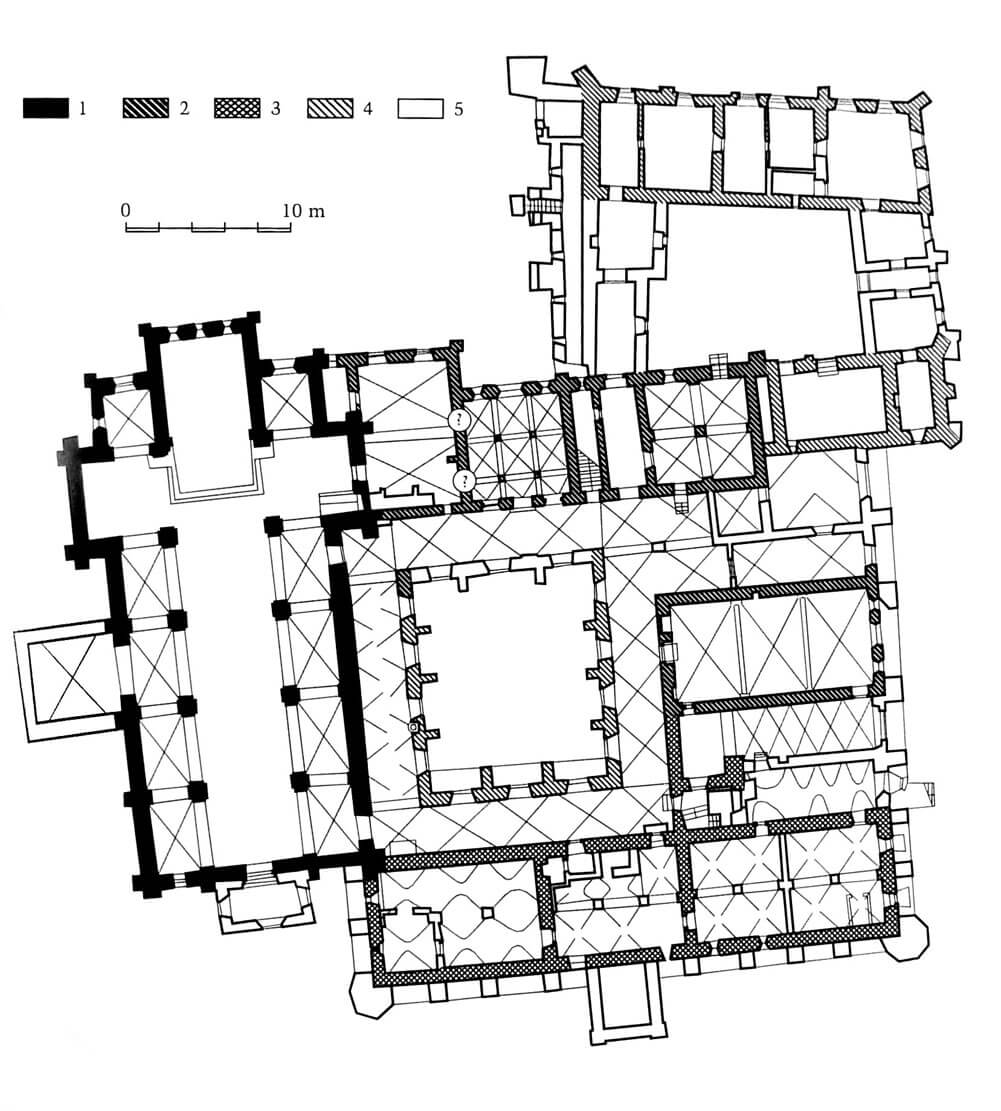

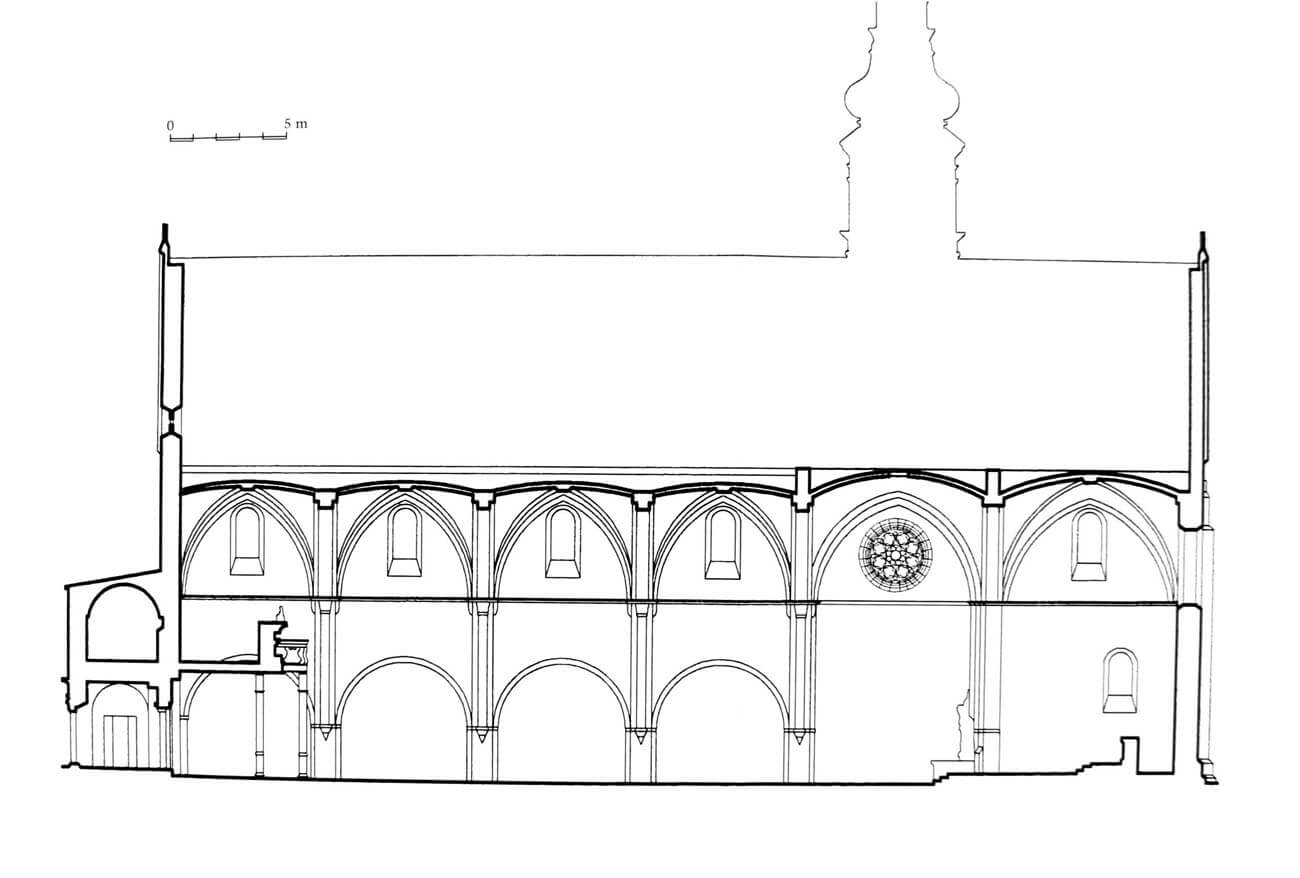

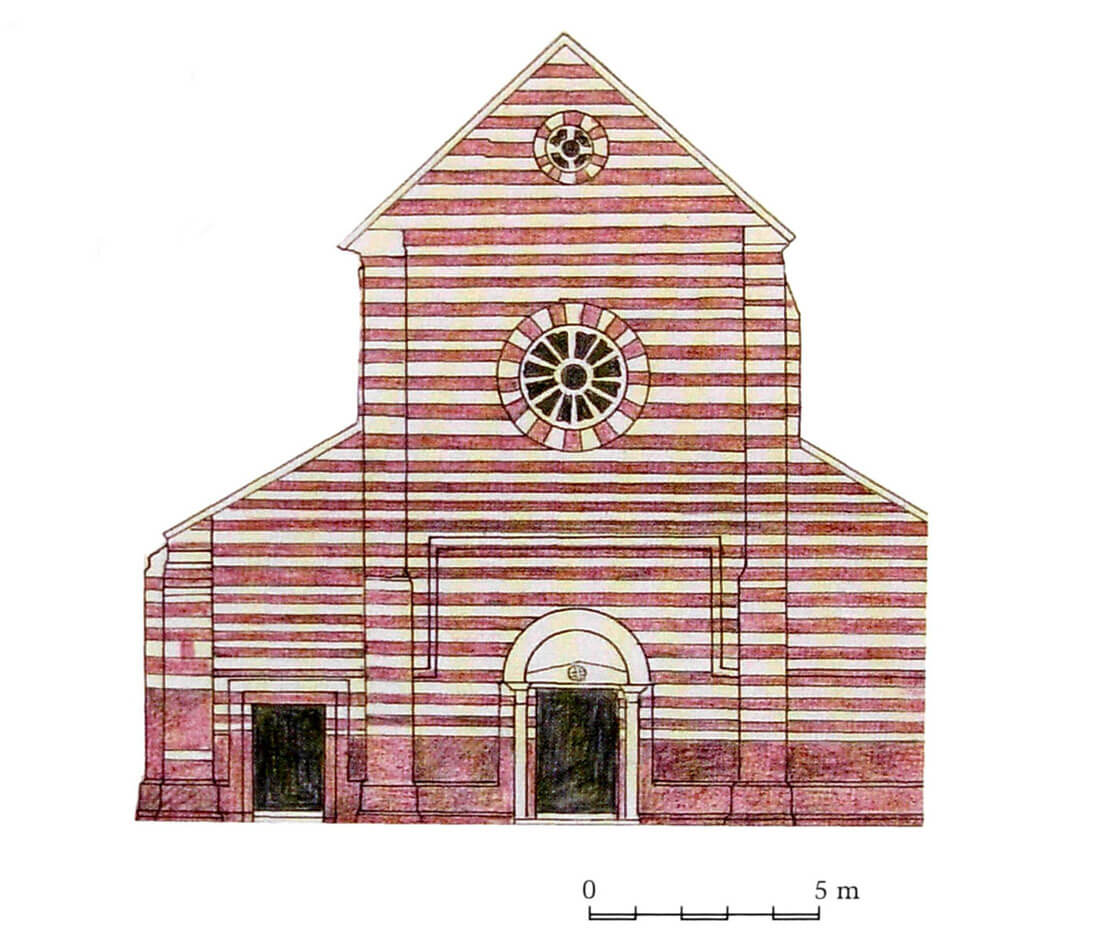

The abbey complex included the church of the Assumed Virgin Mary and Saint Florian and monastery buildings. The church, erected until around the second quarter of the thirteenth century, received the form of a orientated building as a towerless basilica with two aisles, on the Latin cross plan. Its facades were erected in the opus emplectum technique with the face formed of characteristic sandstone blocks arranged in two-colored stripes: yellowish and brown-red. A four-bay nave with dimensions of 17.2 x 26 meters was built of them, with a particularly carefully made west facade, a transept measuring 21.1 x 6.4 meters and a four-sided, single-bay chancel with a length of 7.4 meters and a width of 6.3 meters. The chancel was adjacent from the north and south by side chapels, opened to transept.

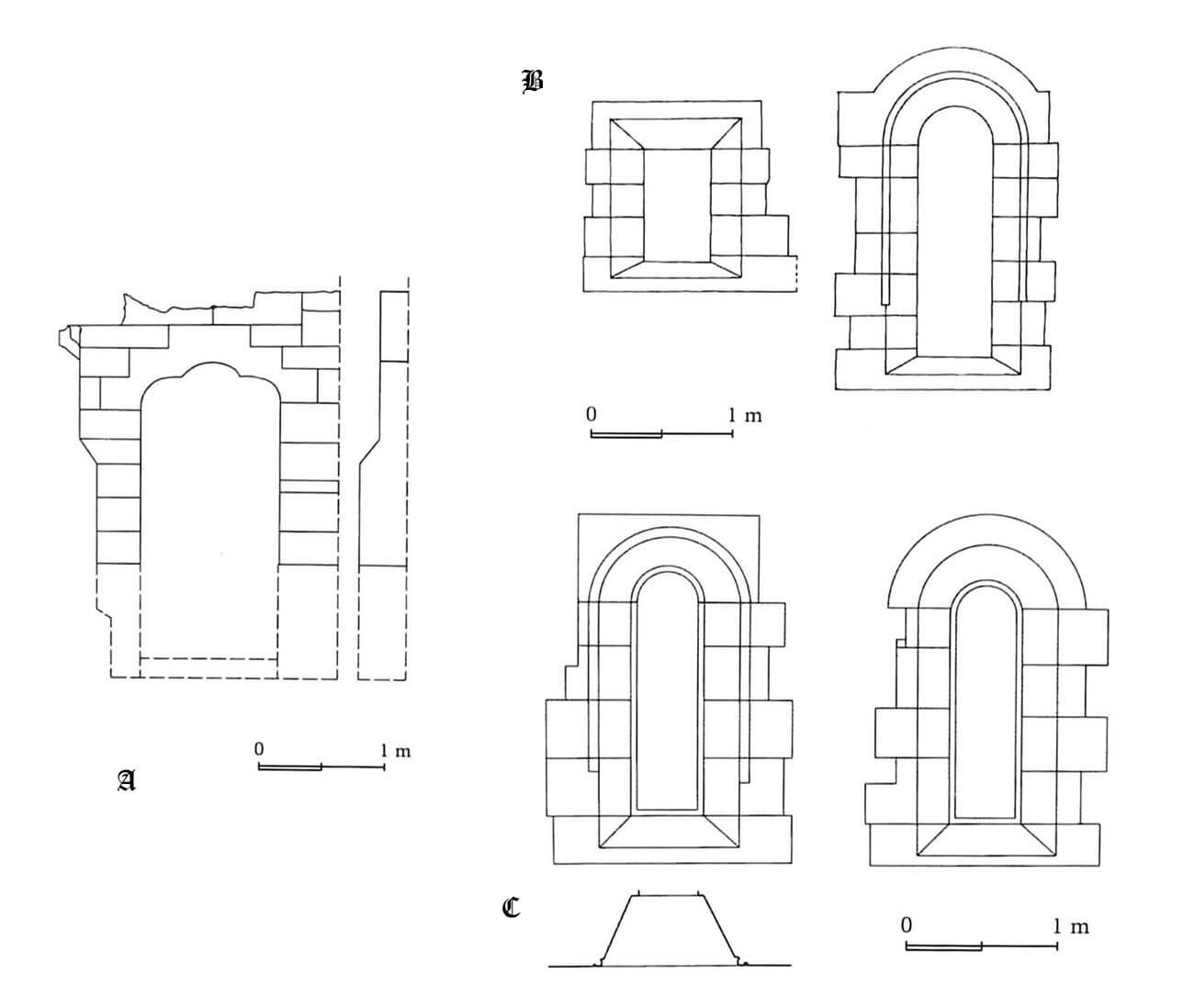

The west facade of the church was decorated with a rosette and a triangular gable. At the ground floor of the west and south façades, two rectangular portals were placed, with the main west decorated with columns with spirally decorated stems, pseudo-Corinthian heads and moulded bases. The columns originally supported a semi-circular tympanum with a relief in the form of a circle with an isosceles cross in the middle. The church was illuminated by small windows with semicircular finials. In addition, moulded frames of round windows, originally decorated with traceries, were placed in the gables. Gothic transformations of the church were limited to raising the gables by about 4 meters, replacing the roofs and inserting a late-Gothic portal in the place of the western entry.

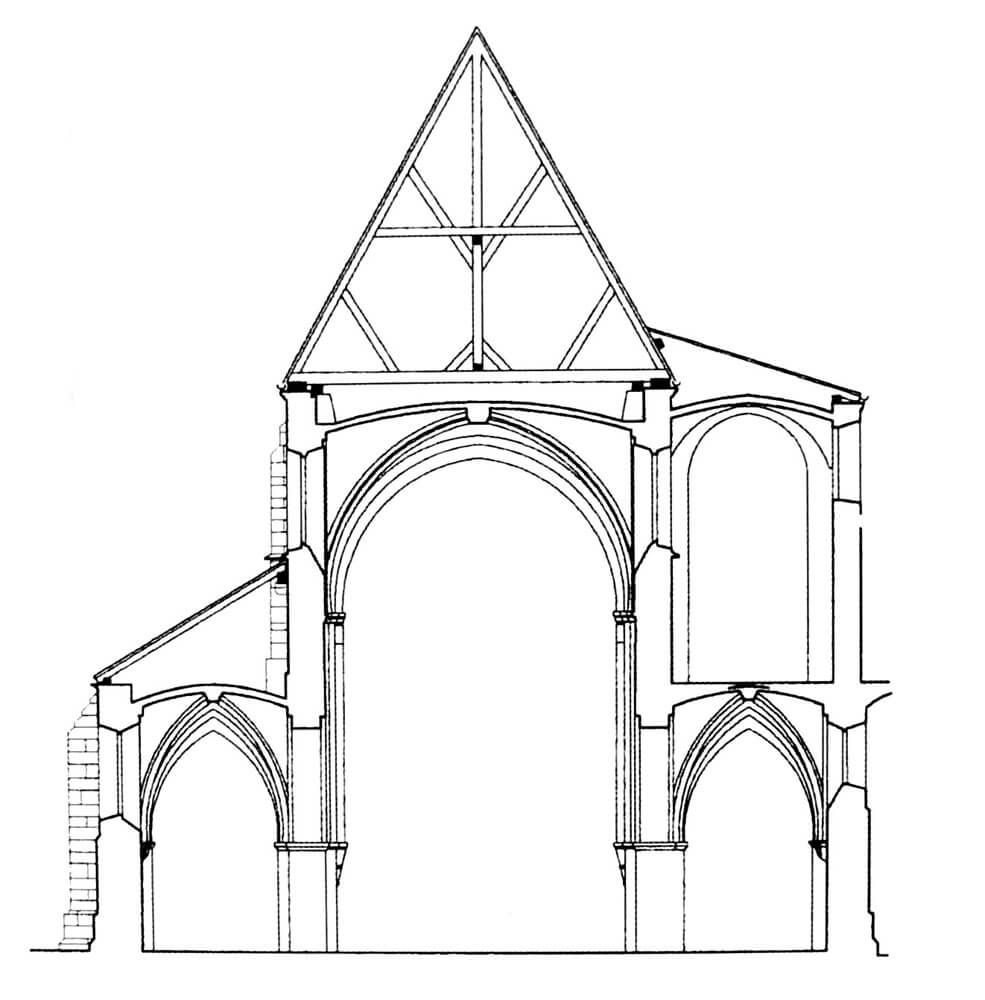

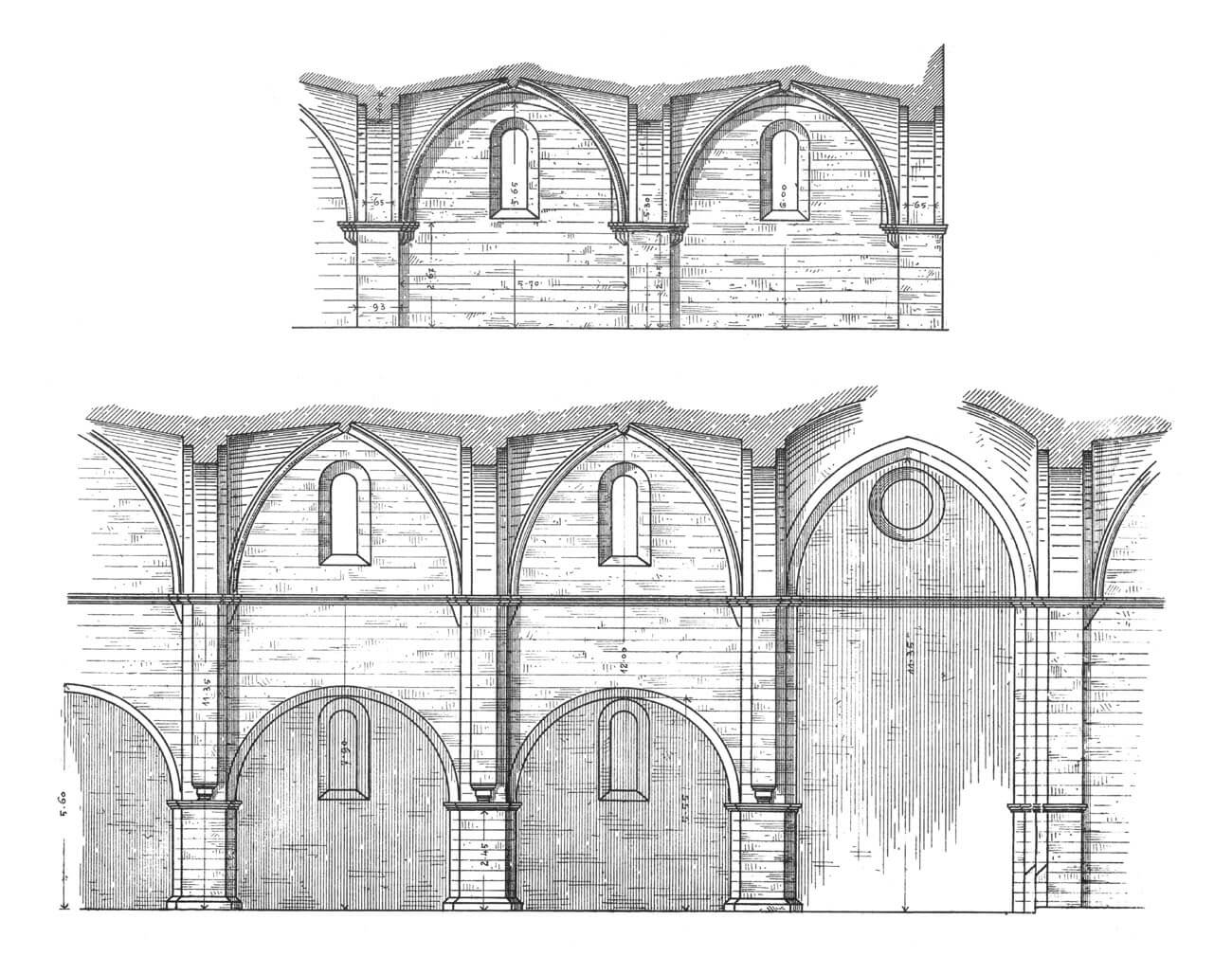

The interior of the church was covered with rib vaults, located in the bays on a rectangular plan. Their ribs were based on suspended semi-columns or pilasters and reinforced with external buttresses, which in the corners received a cross form. The arch bands in the central nave were placed on suspended semi-columns with inverted cone-shaped corbels and leafy heads, and in the aisles on pilasters. In the aisles support was provided by impost cornices of the inter-nave and wall pillars, while the springers of the ribs on the sides of the arch bands were in the form of corbels shaped as inverted cones. The aisles were separated by semicircular arcades, above which the upper level was separated by a band cornice, passing into the imposts of pilasters and corbels. Similar divisions were used in the transept and chancel, but the supports were shaped differently. The original color of the interior of the church was probably also based on two colors (as well as external facades). It is known that the window frames were painted in white and black stripes, referring to the arrangement of stone blocks.

The communication of the church with the area in front of the abbey and with the buildings was provided by the two aforementioned portals in the west facade and a portal in the eastern bay of the southern aisle, leading to the cloister. The sacristy and the dormitory on the first floor were also connected to the transept. The attic over the northern aisle was probably accessed by stairs located in the western wall of the transept. Further on to the attic above the central nave and the chancel, one could go through a staircase located at the north wall of the central nave and placed in a bay window based on a squinch.

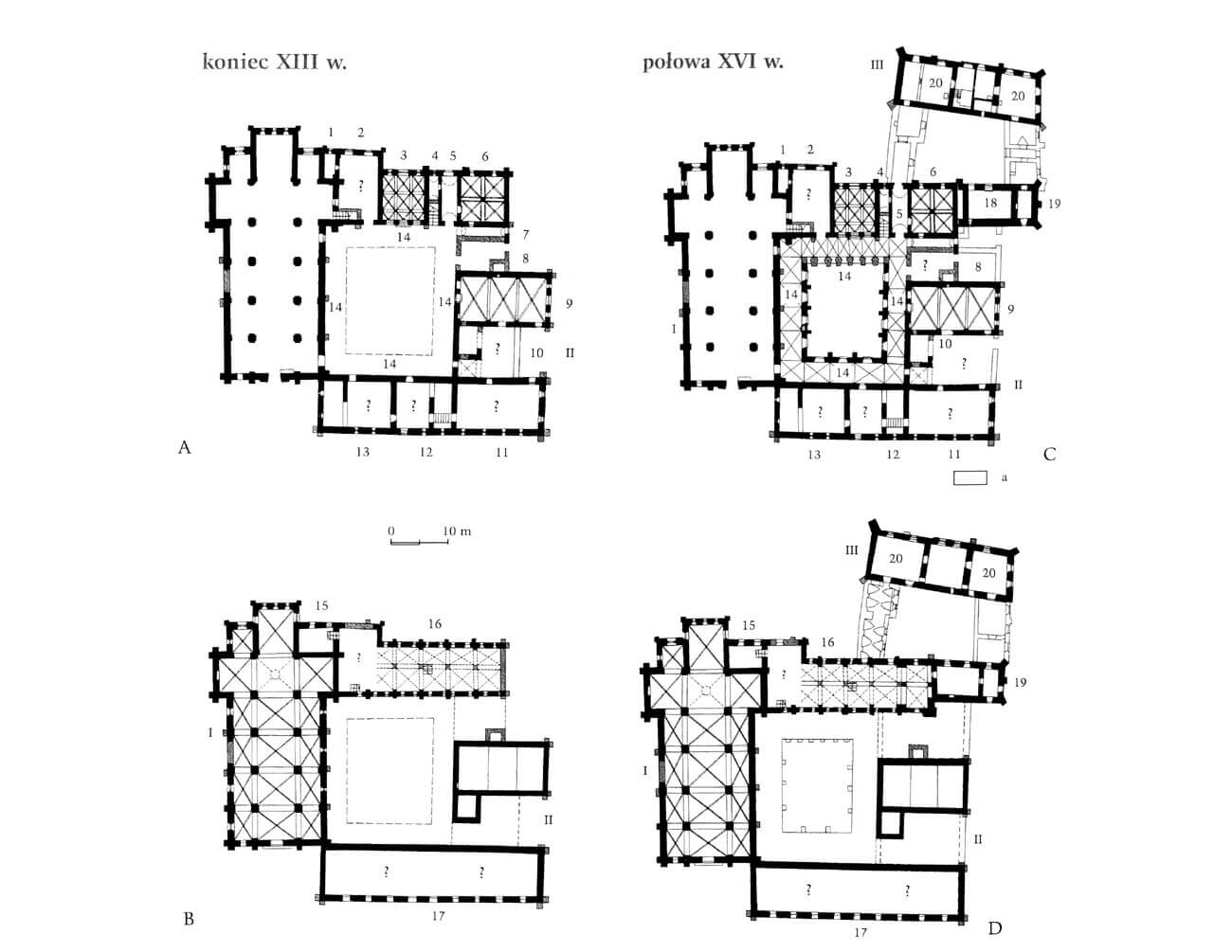

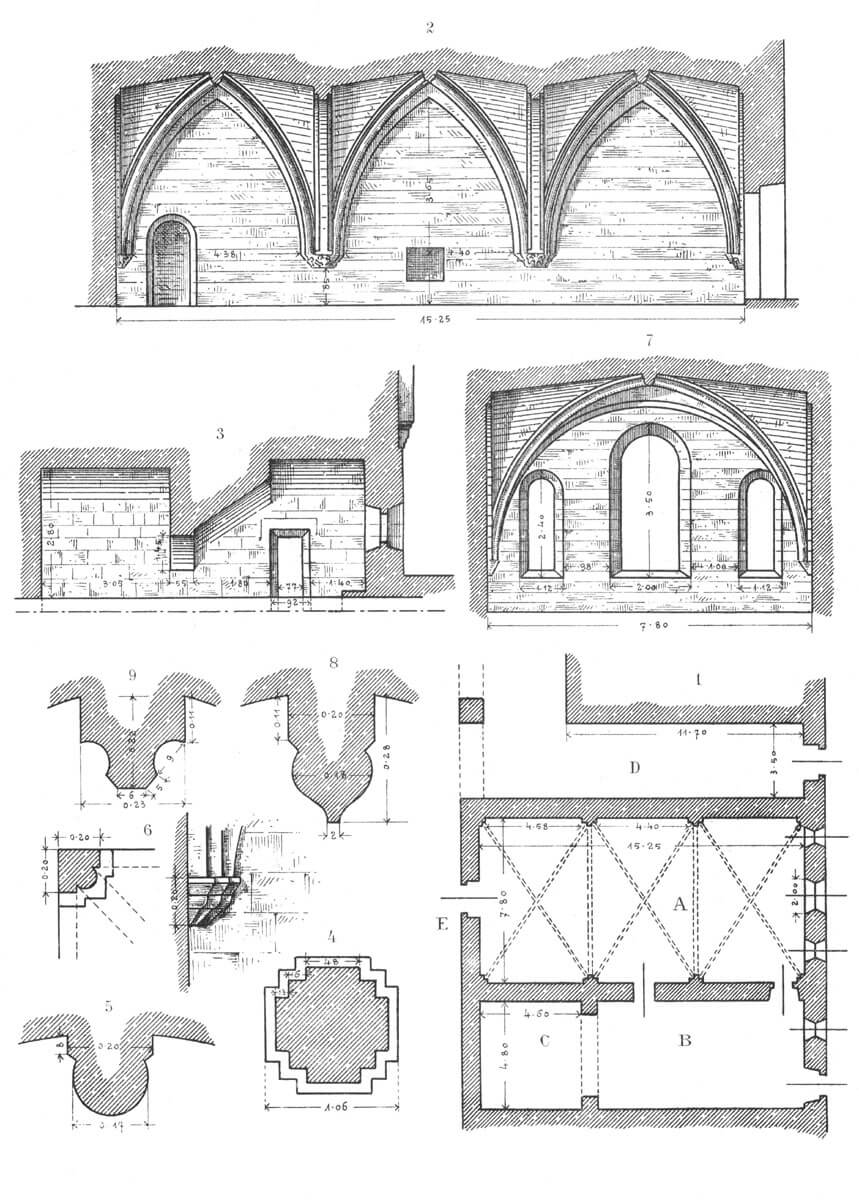

From the south, a enclosure quadrangle was attached to the church in the second quarter of the thirteenth century, located around a cloister running around a inner courtyard of 14.3 x 16.7 meters. At the ground floor of the oldest and most carefully erected east wing, 7.8 meters wide, a small treasury was placed from the north (between the side chapel and the transept), the sacristy bordering the southern wall of the transept, then the chapter house, that is, the meeting place of the monks and a staircase leading to the first floor to the dormitory, under which prison cell was located, connected by a passage with an impressive eastern vestibule, covered with a barrel vault. The last room of the east wing was a fraternity, that is a day room for performing manual work, especially on cold winter days. In the late Middle Ages, the east wing was extended by a two-storey extension with latrines, probably located above the canal that was flushing the impurities.

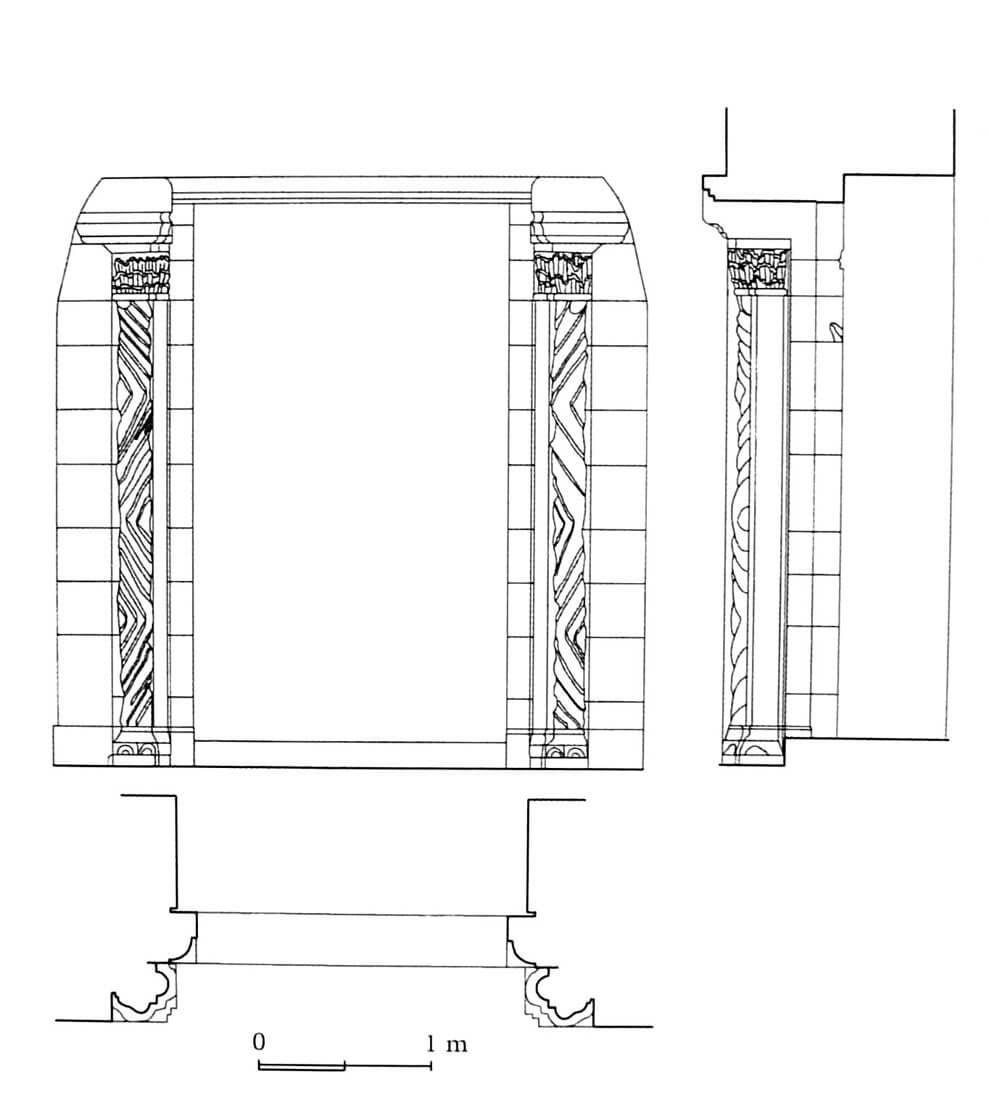

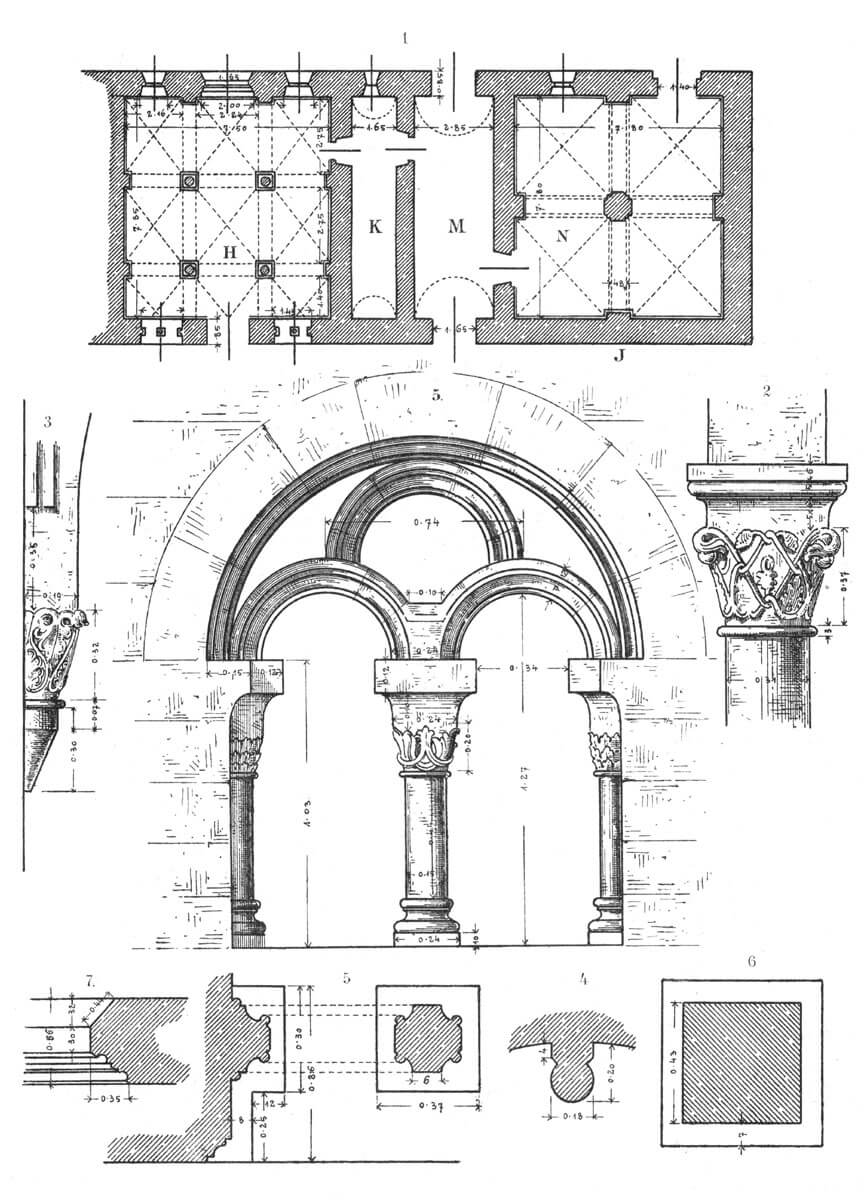

The chapter house was founded on a square plan (7.8 x 7.5 meters) with a rib vault supported by four columns. The entrance to it led from the cloisters through a stately portal with a semicircular archivolt and columns at the sides. On its sides were symmetrical arranged two-light window openings with columns and openwork traceries. All the heads and bases and tracery arcades were decorated with carved ornament. The chapter hall lighting was also provided by a large moulded rosette in the eastern wall with two windows with semicircular finials on the sides. Nine bays of the rib vault were supported on band arches, and the ribs were fastened with bosses. A construction trick was used, consisting in attaching not full bays to the wall from the cloister side, but their halves, so that the vault would not obscure the chapter house windows from the cloister side. Ribs were based on the already mentioned four columns with richly decorated heads, originally covered with colorful polychrome, and on the wall corbels. The bases of the columns were decorated with crockets resembling of animal heads and curling lilies, while on the heads of the corbels there were leaf motifs, sometimes sticking out of the animal mouths. On the sides of the room, next to the walls, originally there were stone benches on which the brothers sat during daily sessions.

The fraternity also called the brothers’ day room was a chamber on a square plan with a rib vault supported by a single, centrally placed pillar. Its stepps were an extension of stone ribs and band arches, which were supported by pilasters on the walls. In addition, in the corners of the fraternity, the ribs were placed on stepped corbels. The interior of the room was illuminated by two rectangular windows located in the eastern wall, while communication was provided by the portal leading to the cloister. The second entrance was probably pierced in the place of the window in the 16th century, after the extension of the wing to the south. Functional architecture devoid of decorations proved the functional character of this room.

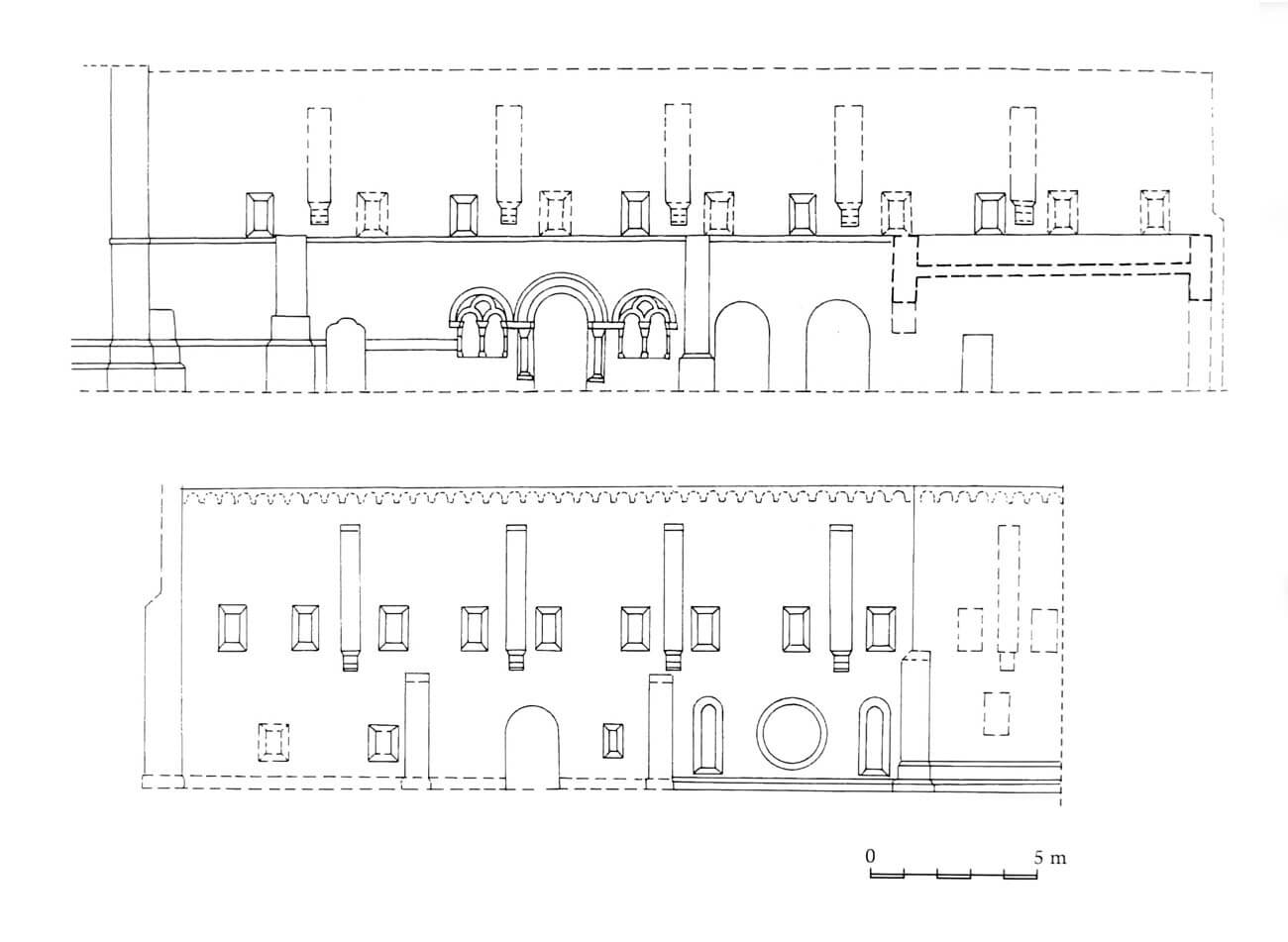

The floor of the entire east wing was occupied by the brothers’ bedroom, a dormitory. It was a two-aisle and six-bay hall, 4.8 meters high, i.e. half a meter higher than the ground floor. You entered it with the so-called day stairs from the side of the cloister and night stairs connected it to the church transept to facilitate the transition to evening prayers. On the eastern side there was an annex illuminated with two windows. Perhaps it was the abbot’s room, before he moved to a separate building. The dormitory was topped with a rib vault supported by wall pilasters and central supports. From the outside, the pilasters were reinforced with suspended lesenes, placed on moulded corbels, above which there was an arcaded frieze. Lighting was provided by small, rectangular windows placed on one level, 12 from the east and 12 from the west wall. During the Gothic period, latrines were added to the southern side, to which two magnificent openings were pierced, perhaps also the function of the abbot’s chamber was changed in connection with the construction of a separate building for him.

The southern wing, of the same width as the eastern wing, housed a refectory with a rib vault and a kitchen made less carefully, perhaps added after a construction break related to the Mongol invasion of 1260. The easternmost part of the southern wing was a narrow, one-story vestibule with a height of about 2.8 meters. It led south, probably to a latrine, perhaps made of wood. In the north-west corner of the vestibule, relics of a floor heating furnace have been discovered, a remnant of the Gothic expansion of the calefactory, which was located west of the vestibule. Calefactory, that is warming room was a chamber, which was the one of the few in the abbey that was heated throughout the winter. The oven placed in it probably also transferred heat to the refectory located next to it, as evidenced by a heating channel in the thickness of the wall with an outlet in the dining room.

The refectory was a spacious, three-bay, rectangular room with a height of 6.4 meters, which was accessed by a semi-circular portal at the north wall, from the cloister. On the sides of the entrance were placed two rectangular niches for dishes, and in the southern bay at a height of half a meter above the floor a semicircular niche for a lector who read while the brothers consumed meals. In the west wall, in the central bay, an opening for serving food was opened in order to facilitate communication with the kitchen. The interior of the refectory was illuminated by three semi-circular windows. This light fell on the rib vaults supported on stone, moulded arch bands and ribs fastened with carved bosses. The walls of the refectory were covered with polychrome. They were pale yellow with painted red lines imitating the arrangement of stone blocks, and additionally painted with a few circles decorated with floral flagella. The arches and ribs were painted in light gray, red and blue-black stripes, while the arch bands were entirely covered in light gray and dismembered with red stripes.

The walls of the kitchen adjacent to the west were made after refectory was erected (a toothing was left in the walls of the dining room for planning further expansion) and a little less carefully. The upper part of the kitchen was built differently, from unworked stones and not from ashlar stones. Its north-eastern part was occupied by a large furnace, above which a large chimney on a square plan was placed. To the west of it, a rectangular part of the kitchen was crowned with a rib vault, above which another room once existed, perhaps a drying room using heat from the chimney flue.

The west wing, measuring 8.1 meters in width according to the layout of typical Cistercian monasteries, was intended for lay brothers. The northern room probably originally contained a two-aisle cellar. To the south of it, the central chamber could act as an entrance vestibule to the abbey, from where it went down a narrow descent with three stairs to a south also two-aisle room located in the south, probably a lay brothers’ refectory adjacent to the kitchen. The west wing was two-story with a lay brothers bedroom upstairs.

The cloister was erected in the second quarter of the 13th century along with the east wing. At that time it was still covered with a wooden roof truss (based on the offset and on the wall on the other side) and a mono-pitched roof. It was used to move between all ranges and to exit to the inner patio, where herbs and vegetables were grown. In addition, it had the function of a place where monks rested, studied, contemplated and performed some rituals or processions. During the Gothic period, the cloister was thoroughly rebuilt and crowned with stone vaults.

Probably in the fourteenth century, on the eastern side of the cloister buildings, a separate, free-standing abbot’s house was built, laid out on the plan of an elongated trapezoid with a slightly sloping southern wall. Its walls, made of erratic stones, were reinforced from the outside with corner buttresses and two buttresses in the middle of the eastern façade. The interior is divided into three main parts. The middle one probably served as a entry lobby, while the side ones had a residential and representative role.

Current state

Wąchock is today one of the best preserved medieval abbeys in Poland. The original church and the four-wing enclosure buildings have survived to a large extent. Despite subsequent transformations, as a result of renovations carried out since the end of the 19th century, its Romanesque relics were exposed, and post-medieval plaster removed from the walls, although the interior remained Baroque due to the early modern polychromies and furnishings. The original block of the church is partly obscured by the 17th-century chapel of St. Wincenty on the north side and a large western porch, housing the original main portal. Unfortunately, the windows in the northern facade and in the side chapels were enlarged in the early modern period. The original one have survived in the facades of the chancel, transept and southern aisle. The vaults with their supporting system have been almost completely preserved, with the exception of the crossing.

Among the monastery buildings, a valuable chapter house with an original rib vault and a refectory in the southern wing have survived. The chapter house reflects on the most beautiful and richly decorated Romanesque interior in Poland, although it suffered due to the removal of stone benches, impost cornices and the lower parts of the corbels. The Romanesque barrel vaulted prison cell, vestibule and day room have also been preserved. The walls of the west wing suffered the most during the fire of 1637, so this part was later thoroughly rebuilt. Its walls were covered with thick plaster and provided with external arcades. The vaults of the Gothic cloister have not survived.

bibliography:

Jarzewicz J., Kościoły romańskie w Polsce, Kraków 2014.

Łużyniecka E., Kunkel R., Świechowski Z., Architektura opactw cysterskich. Małopolskie filie Morimond, Wrocław 2008.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.