History

The abbey founded probably Kazimierz I the Restorer in 1044, after the crisis of a young state, triggered by the pagan rebellion and the Czech invasion. The Benedictines were to support the reconstruction of the state and the Church. The first abbot was Aaron, who also served as bishop of Cracow and archbishop. It is possible, however, that the Tyniec abbey was founded for the Benedictines, previously present in Kraków, only by the son of Kazimierz the Restorer, Bolesław II the Generous. Because according to the document of legate Giles from around 1125, the abbey’s income was supposed to come from this ruler.

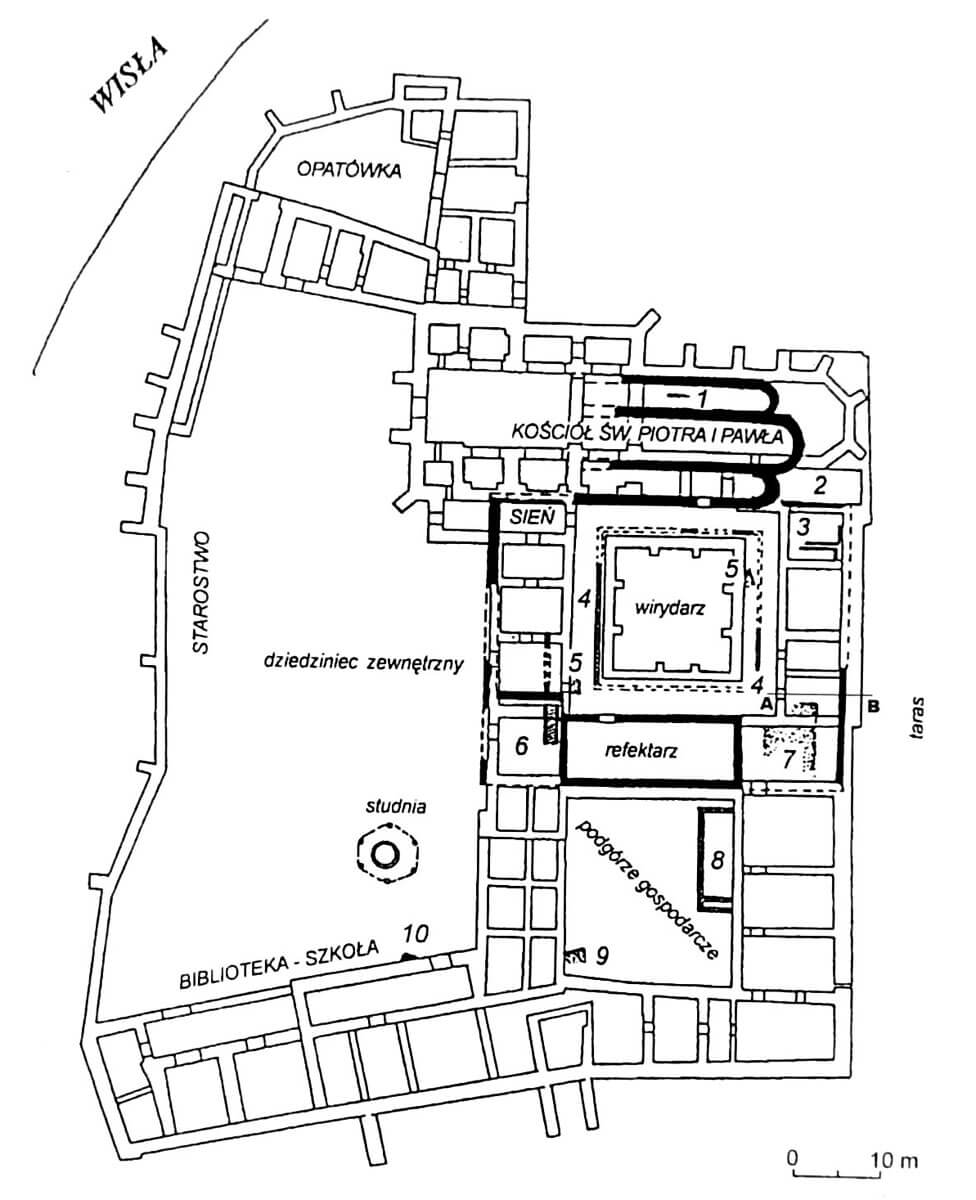

In the second half of the 11th century, a complex of Romanesque buildings was built: a three-aisle basilica and the oldest stone monastery buildings. In the mid-13th century, the abbey was secured with fortifications (probably located on the opposite side of the Vistula, in Piekary) in connection with the battles for the Kraków throne between Konrad Mazowiecki and his allies and Bolesław the Chaste. Despite this, in 1260 the abbey was destroyed by the Mongol invasion, after which the buildings were rebuilt in the early Gothic style.

In 1306, Tyniec was devastated as a result of an attack by Gerlach de Culpen, an ally of the bishop of Kraków, Jan Muskata, who fought against Prince Władysław Łokietek. At that time (or in the second half of the 13th century) a castle was erected on the abbey, which was to serve as a border royal stronghold, but already in the 14th century it was rather a fortified residence of the abbot, the center for managing of the abbey property and the place of exercising the judiciary. If this building had any strategic significance, it lost it in the second half of the 15th century, when in 1457 King Kazimierz Jagiellończyk bought the Duchy of Oświęcim and Zator. It was their neighborhood and hostile relations with the abbey that caused that some of the abbey goods suffered at that time, and one of the monks, sent as an envoy with a petition to the princes to Zator, was flogged and beaten, and as a result he died. The last sign of king’s interest in the Tyniec castle was the privilege issued by Sigismund the Old in 1509 for the allocation of salt in the Wieliczka salt mine to support the collapsing stronghold. In this document, however, there was no mention of the royal crew, or of any special function performed by the castle, much less that it was owned by the monarch. Perhaps, in a petition addressed to the king, the abbot referred to the motives related to the function of the abbey as a watchtower in an attempt to raise funds for the renovation works. The castle itself was rather a defensive residence of the abbot, in which perhaps Queen Jadwiga, who visited the abbey in 1394, stayed overnight, or the chronicler Jan Długosz lived with the young princes in 1467 and at the beginning of 1468, and many other guests of Tyniec abbots.

In the third quarter of the 15th century, during the time of abbot Maciej Skawinka, the abbey was rebuilt in the Gothic style, in the second half of the 16th century, the Tyniec castle was substantially rebuilt in the Renaissance style by abbot Hieronim Krzyżanowski, and at the end of the 16th century, abbot Andrzej Brzechwa rebuilt and enlarged the monastery buildings. In the following centuries works were carried out in the abbey in the Baroque style, which began with the transformation of the church around 1616-1622. The convent was ravaged and burnt by the Swedes in 1656, but soon its buildings were rebuilt and enlarged. The abbey suffered further destruction due to their transformation into a fortress of the Bar Confederates at the end of the 18th century. In 1817, the convent was liquidated. After the period of neglect in the nineteenth century, the monks returned to Tyniec in 1939, and in 1947 began rebuilding the dilapidated complex.

The abbey was situated on the limestone Monastery Hill, descending on the western side with vertical, rocky slopes towards the Vistula River. Also from the south and east the slopes were high, which made the only convenient access road possible from the north. There was a river crossing near the abbey, but it was important primarily for local transport.

The oldest stone sacral building on Tyniec Hill, dating from the 60-70s of the 11th century, was to be a rectangular chapel (located on the site of the later sacristy), with dimensions of about 6.5 x 9 meters and a height of about 8 meters. After 1260, the chapel, destroyed during the Mongol invasion, was replaced with a new one, on the plan of an elongated rectangle closed from the east with an apse. It had dimensions of 3.60 x 12 meters with three square bays separated by arch bands, and a cross vault supported by half-columns. A portal embedded in the southern wall led to the chapel.

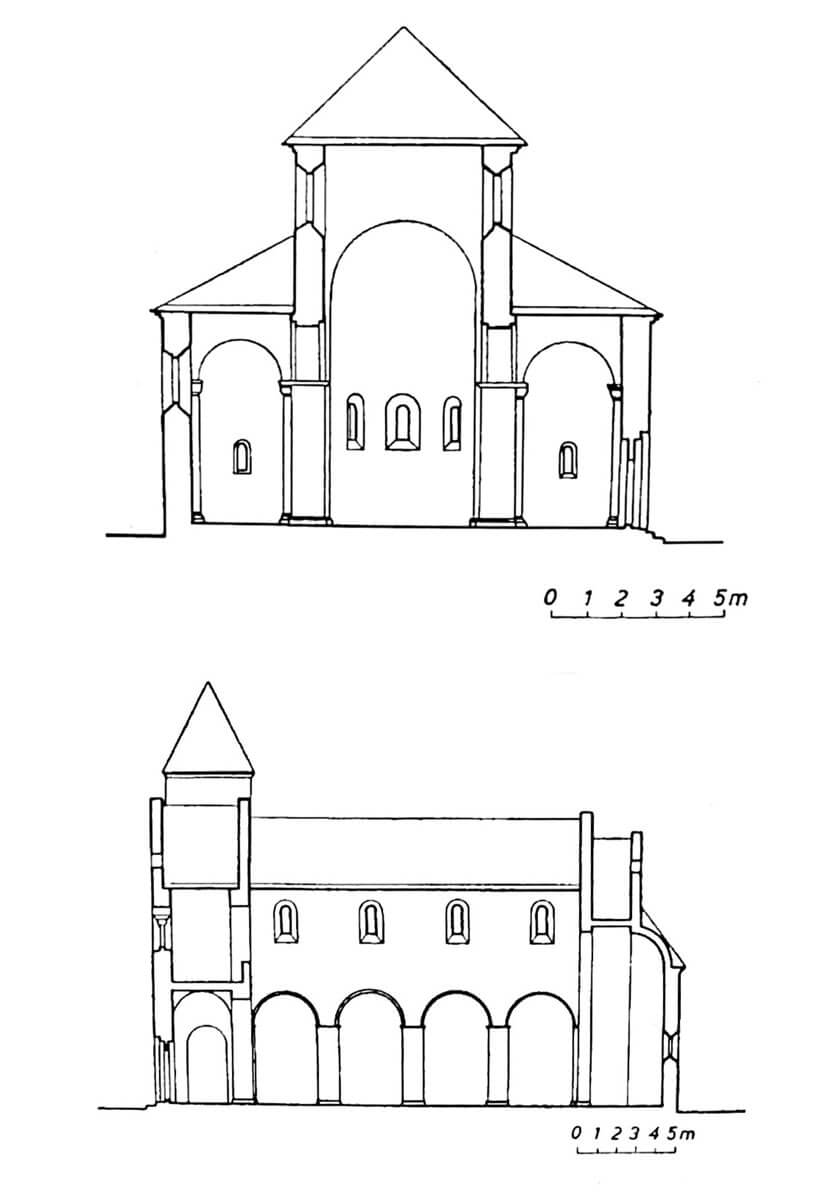

The Romanesque church from the times of Kazimierz the Restorer was built in the opus emplectum technique of sandstone cubes (reinforced in the corners with larger blocks), a three-aisle basilica without a transept, probably with two or possibly one tower on the west. From the east, the building was probably closed with three apses, one at the end of each aisle. The middle one was preceded by a short presbytery four-sided bay. The form of the church in the form of a transept-free basilica was common in Romanesque architecture, with the Benedictine abbeys closest to the Tyniec church being located in the settlements of Hronsky Beńadik, Diakovce, Somogyvar and Kapornakp. Tyniec also showed great architectural ties with the Wawel church of St. Geron (stonework, a cord motif on the half-columns and vaults in the aisles). The Tyniec church was 24.1 meters long and 12.1 meters wide. The aisles were separated from each other by pillars, in the nave with square one with half-columns from the side of the aisles and cross one in the western bay. There was an avant-corps about 1 meter long on the extension of the nave in the west facade. The eastern choir was conch-vaulted (apses) and barrel-vaulted (presbytery), the central nave was covered with a ceiling or an open roof truss, while the aisles had a cross vault with arch bands. The tripartite western part included a vestibule open with arcades towards the aisles. In the central part of the façade, flanked by two towers, there was a gallery.

In the second half of the thirteenth century, or at the beginning of the fourteenth century, the church was rebuilt in the early Gothic style. It was partially added to the northern wall of the Romanesque basilica with the use of limestone and sandstone blocks. In the third quarter of the 15th century, the church was rebuilt in the Gothic style into a four-bay hall with central nave and two aisles, with an elongated, three-bay, pentagonally ended chancel and a chapel in the extension of the southern aisle and a square tower in the north-western part. The walls of the church were enclosed with a plinth and buttresses, set at an angle in the corners. The southern windows of the church were splayed on both sides, equipped with two-light tracery.

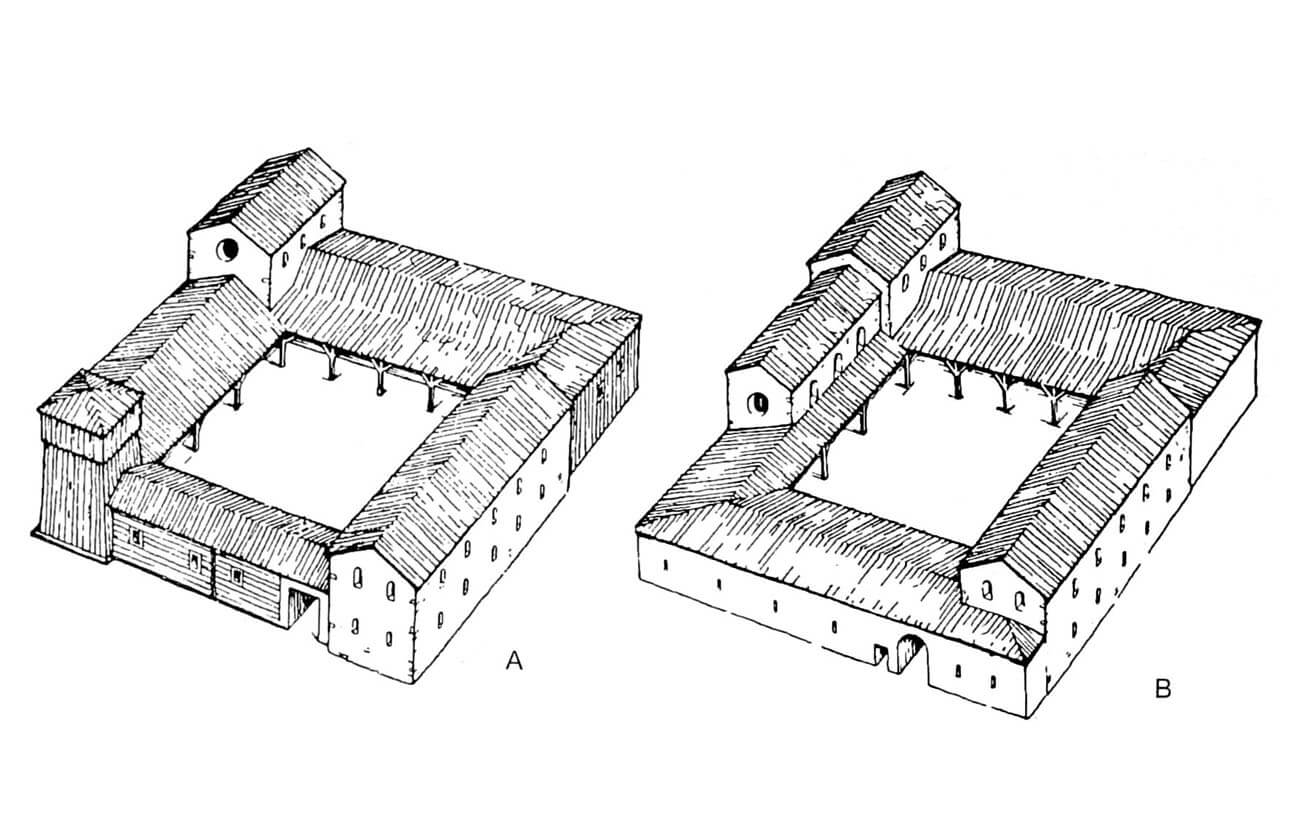

From the south, the church was adjoined by Romanesque monastery buildings surrounding the courtyard, 14 meters long sides with originally wooden cloisters. In the oldest phase, only the building on the south side, measuring 8.6 x 19.8 meters, functioned. It was made of limestone with which the sandstone window openings and the portal (both preserved in the western wall). The building had two floors: probably there was a refectory at the bottom, and a dormitory at the top. The refectory floor was slightly more than half a meter lower than the level of the cloister and less than two meters below the oratory (church) floor, which was located at the opposite end of the monastery complex, surrounded by a wooden fence. What’s more, in the Gothic period, the interior of the refectory was deepened by about 1.5 meters, using a secondary Romanesque cube. The cellar of unknown function thus obtained was plastered and whitewashed.

With time, a Romanesque stone west wing also appeared (probably with the function of a cellarium), added with the shorter side to the church. In its southern part there was a vaulted channel 4.6 meters long and less than a meter high, closed in a semicircle from the south. It was made of limestone, covered with a barrel vault, and in both of its gable walls there were rectangular openings framed with sandstone. The continuation of the northern opening was a brick canal located in the thickness of the Romanesque wall. The whole could function as a sewage system or be a kind of rainwater cistern. Other buildings, probably wooden, could have been located along the fence. The courtyard in the center was transformed into cloisters over time. The Romanesque cloisters were probably not fully built due to the invasions, but the found relics may indicate that it was planned to put openings to the inner patio with arcades based on double columns.

Rebuilt after being destroyed by the Mongols in 1260, the monastery was surrounded by a 1.5-meter-thick sandstone wall. The entire complex was then a square plan with a side of 40 meters, and there was a gate located in the south-west corner. The southern wing with the refectory and kitchen still functioned, the west wing with the cellarium, over time also the stone buildings of the eastern wing were formed, in which the sacristy by the church, chapter house and a new dormitory were placed. In the late Gothic period, three, already two-story wings of the claustrum still functioned. The chapter house, originally covered with a timber ceiling, was crowned with a cross-rib vault with a bas-relief Rawicz coat of arms on a circular boss. The cloisters from the inner garth side were supported by buttresses, while inside they were vaulted with ribs fastened with bosses with the abbey’s coats of arms, Rawicz, Jelita and house marks. Their lighting was provided by large, pointed windows, splayed on both sides. The extension of the complex on the south side, where originally there were freestanding wooden auxiliary buildings, created another three-wing complex with an internal, second patio. In its south-west part there was a library.

The entrance to the abbey was located on the north-west side. Due to its key location, a stronghold was erected there, and then a 14th-century castle, which was more of a gatehouse and a fortified abbot’s residence with guest rooms for visitors to the abbey, than a typical castle with a permanent crew. It was probably founded on a plan similar to a triangle, with one tower over the Vistula embankment and two residential wings. The castle and monastery buildings of the abbey were surrounded by thick walls, equipped with a walkway for guards and battlement.

Current state

Today in the Tyniec monastery there are both Romanesque and Gothic and unfortunately Baroque elements. From the earliest period, the walls of the church have preserved up to about 5 meters high, the wall between the temple and the cloisters with the Romanesque portal and the walls of the refectory. The cloisters come from the 15th century, with the exception of the southern arm, which was demolished in the 19th century and then reconstructed. The chancel of the church now also has Gothic forms, as are the walls in the southern and western parts of the monastic complex. Among the Gothic architectural details, there are bas-relief bosses of the vaults in the chapter house and cloisters, a window in the treasury topped with a trefoil, a moulded portal in the west wing, a portal in the southern part of the abbey, and a western portal in the church. The abbey still performs religious functions, but its part is open to the public. Practical information for tourists can be found on the abbey website here.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Bober M., Architektura przedromańska i romańska w Krakowie. Badania i interpretacje, Rzeszów 2008.

Jarzewicz J., Kościoły romańskie w Polsce, Kraków 2014.

Gronowski M., Zamek w Tyńcu, “Średniowiecze Polskie i Powszechne”, 1 (5), 2009.

Kamińska M., Aktualny stan badań i nowe koncepcje interpretacyjne romańskiego Tyńca [w:] Kraków romański, red. J.M.Małecki, Kraków 2014.

Krasnowolski B., Leksykon zabytków architektury Małopolski, Warszawa 2013.

Sztuka polska przedromańska i romańska do schyłku XIII wieku, red. M. Walicki, Warszawa 1971.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.

Świechowski Z., Sztuka romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 1990.