History

The nunnery in Trzebnica was founded in 1202, after several years of efforts, by Prince Henry the Bearded, acting under the influence of his wife Jadwiga (Hedwig). It became the seat of the first female convent in Poland, intended for Benedictines, brought a year later from the monastery of St. Teodor at Bamberg and settled in Trzebnica, a market village mentioned in the first half of the 12th century. A few days after the arrival of the nuns, they received the approval of the head of the Polish Church, the Archbishop of Gniezno, Henryk Kietlicz, and selected a first abbes named Petrussa. Prince Henry gave the nunnery rich salary, which included Trzebnica and 12 surrounding villages, and Cistercians from Lubiąż also offered help.

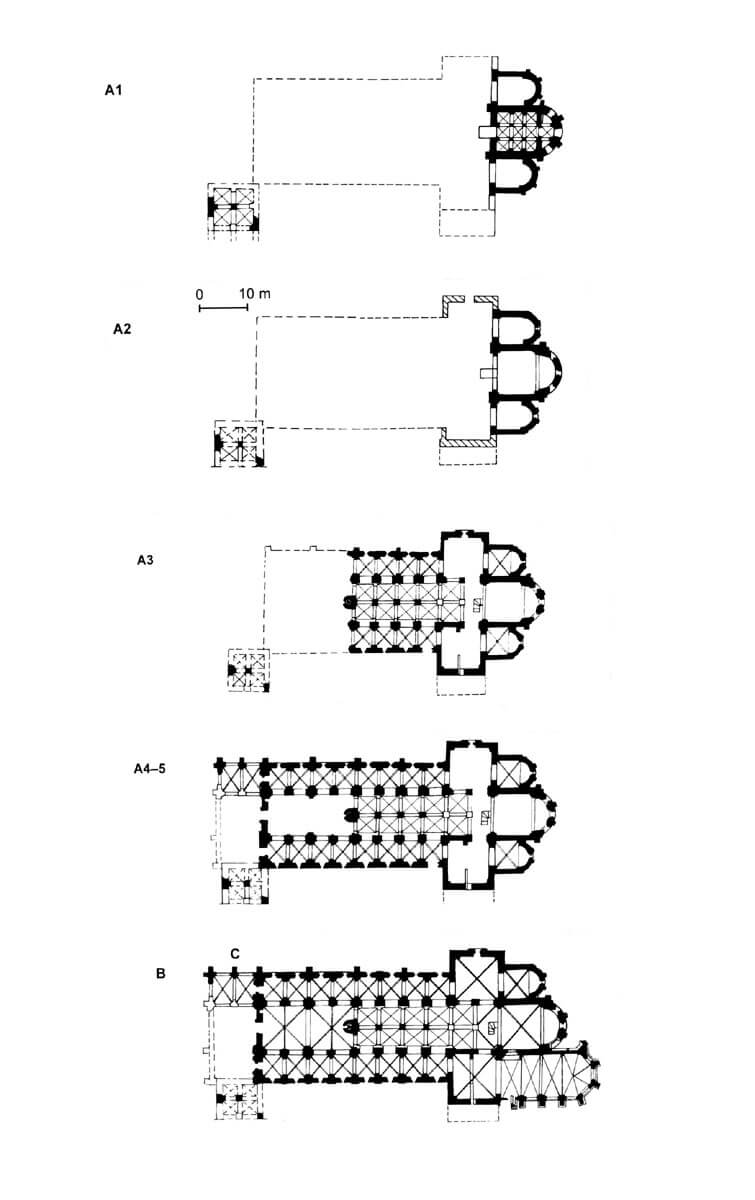

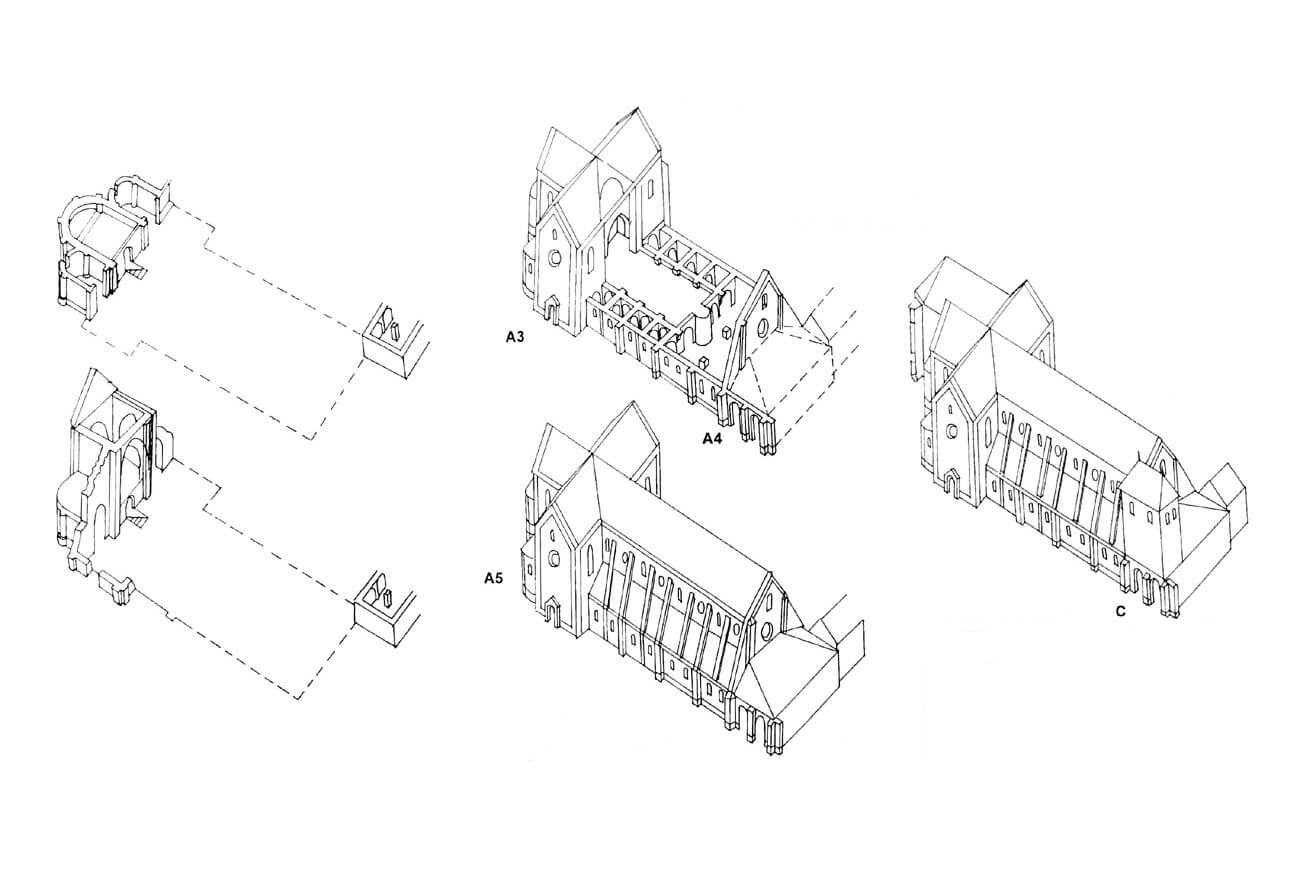

Soon after the arrival of the convent in Trzebnica, the construction of one of the first brick churches in the Romanesque style in Poland began. The first reference to the construction dates back to 1204, when prince Henry the Bearded gave the nunnery a certain Dalemir to prepare the mortar. In 1208, a grant was issued for the stonemason James, and in 1214, an indulgence was granted to visitors to the monastery crypt on the anniversary of its consecration. It was erected together with the chancel and side chapels in the first stage of works. The rest of the church was completed in the second stage, differing in architectural details and the difference in level between the chancel and the transept, which probably resulted from a change in the concept and construction workshop. The consecration of the completed church took place in 1219.

In 1218, the Trzebnica convent was incorporated into the male Cistercian abbeys and subordinated to the older male abbey, elected by the Cistercian General Chapter. Initially, they were the abbots of Saxony’s Pforta, but a year later this function was entrusted to the abbots of Lubiąż Abbey. When in 1218 the first abbes of Trzebnica died, Gertruda was chosen her successor, daughter of duchess Jadwiga, although in practice it was the mother, a later saint, who had the decisive voice in matters of the nunnery. In the 1230s she moved permanently to Trzebnica, but did not make order vows. Her high position, personality and special authority meant that the abbey had a wide impact on external life. In 1238, the Prince Henry the Bearded was buried in it, and in 1243 Jadwiga herself. After her canonization in 1267, a mass influx of pilgrims to Trzebnica began and the cult of this saint developed. That is why in the years 1268-1269 the grandson of the duchess, Władysław, the archbishop of Salzburg, founded the chapel of St. Hedwig, which was the first building in Poland built entirely in the Gothic style. The remains of St. Hedwig were placed in the chapel, the Czech king Ottokar II also married there. The high rank of the abbey is also evidenced by the fact that from 1214 Czech princesses lived here and grew up for several years: Agnes with her sister Anna, later wife of Henry the Pious. From the very beginning, the basilica became the mausoleum of the Silesian Piasts, in total 22 representatives of this family were buried here, and by 1515 all the abbeses were elected from among the members of this dynasty.

In 1414 a fire broke out in the abbey. Hussites invasions combined with the devastation of abbey and monasteries lands in 1432 and 1433, and then the destruction in 1475 by the Hungarian army of Corvinus, initiated a long period of decline and stagnation of the nunnery, perpetuated by Silesian entanglement with religious disputes connected with the expansion of Protestantism. In 1464, as a result of a lightning strike in the church, the roof of the chapel was destroyed, however, the nunnery survived. Another fire touched the monastery and church in 1486, then in 1505 and 1595. As a result, the nunnery was partially burnt, and in 1626 ravaged by the Danish army of Count Mansfeld..

It was not until the increasing prosperity of Silesia and its recatholisation, after the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648 and the victorious war with Turkey, created an economically and politically advantageous base for increasing the worship of St. Hedwig, with which both Poles and Catholic Habsburgs were identified. The first works on the renovation of the temple began in 1676. The baroquesation of the church and abbey took place in the second half of the 17th century and in the 18th century. In 1810 the nunnery was secularized. The valuable collection and numerous interior furnishings were transferred to Wrocław, and in the monastery a military hospital was created. In 1870 the owners of the nunnery became Knights Hospitaller, and in 1889 the Sisters of Mercy of St. Borromeo. Both orders have managed hospitals in their parts. In the 1930s renovation works were started, also continued after the war. After the transfer of the hospital, all the monastery buildings were taken over by the Sisters of Mercy of St. Borromeo.

Architecture

The Trzebnica abbey was located in the not too deep valley of the Cat’s Mountains, in the vicinity of dense forests, although Trzebnica itself was already a developed market settlement with a parish church and probably with a prince’s seat on the north-west edge of the village. The area of the nunnery descending from west to east was surrounded by a wall, with the abbey church built in the highest place. A small river flowed east of the monastery, swamps and ponds stretched to the south. The convent consisted of a church, claustrum buildings and utility, economic rooms.

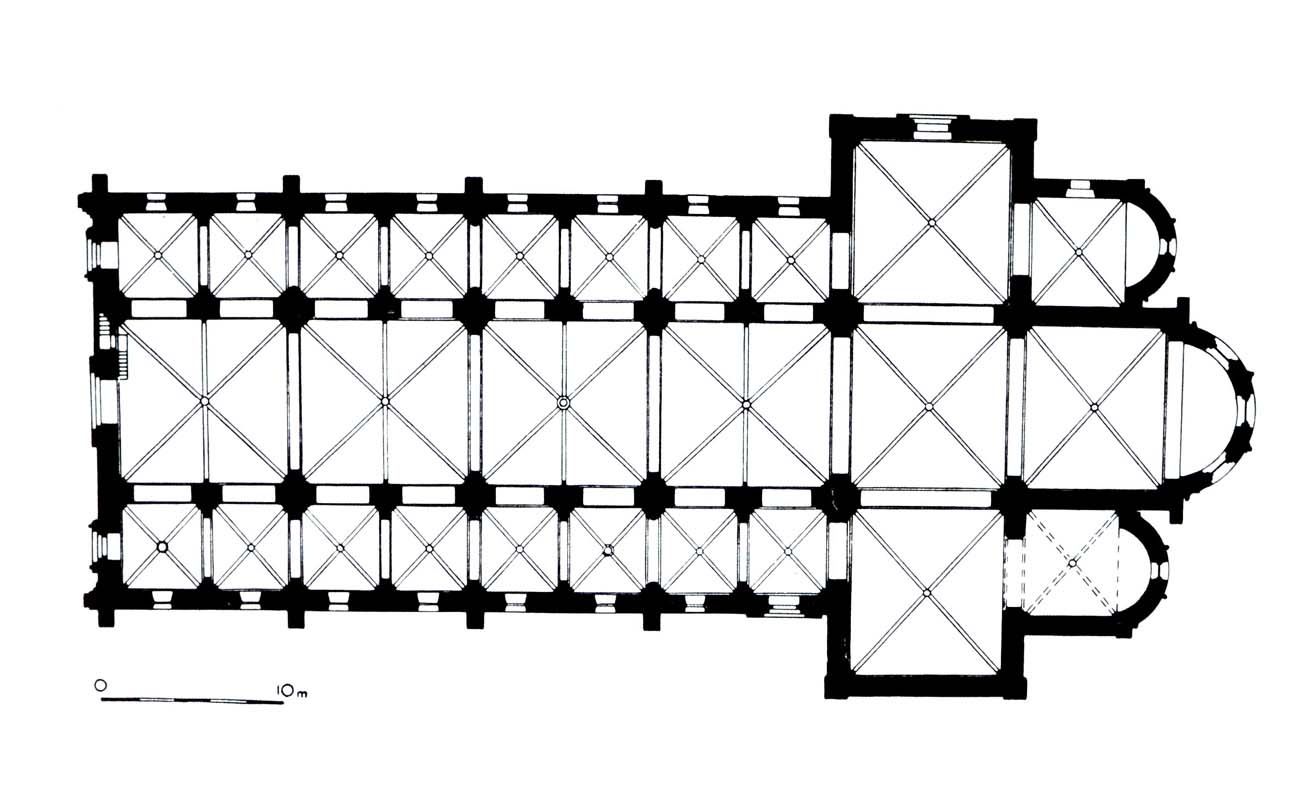

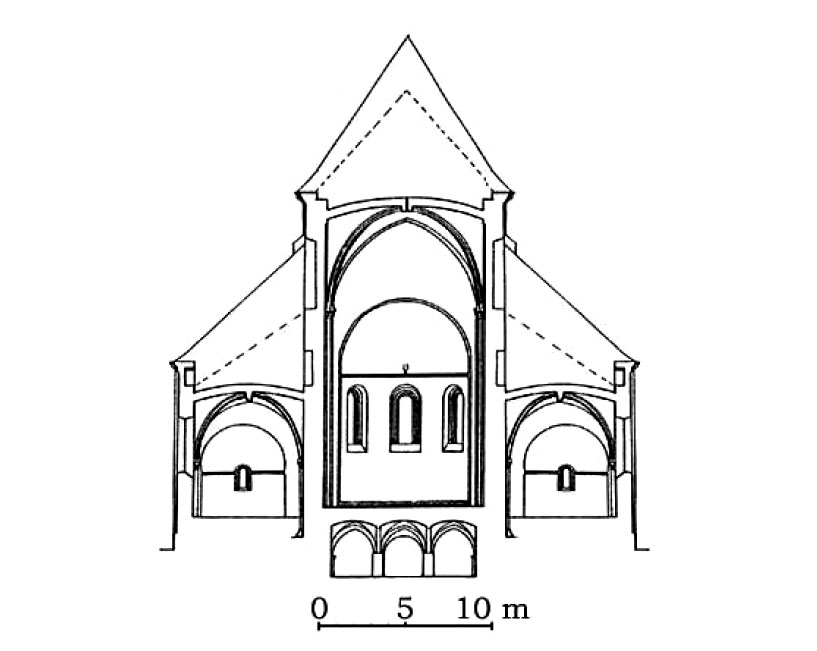

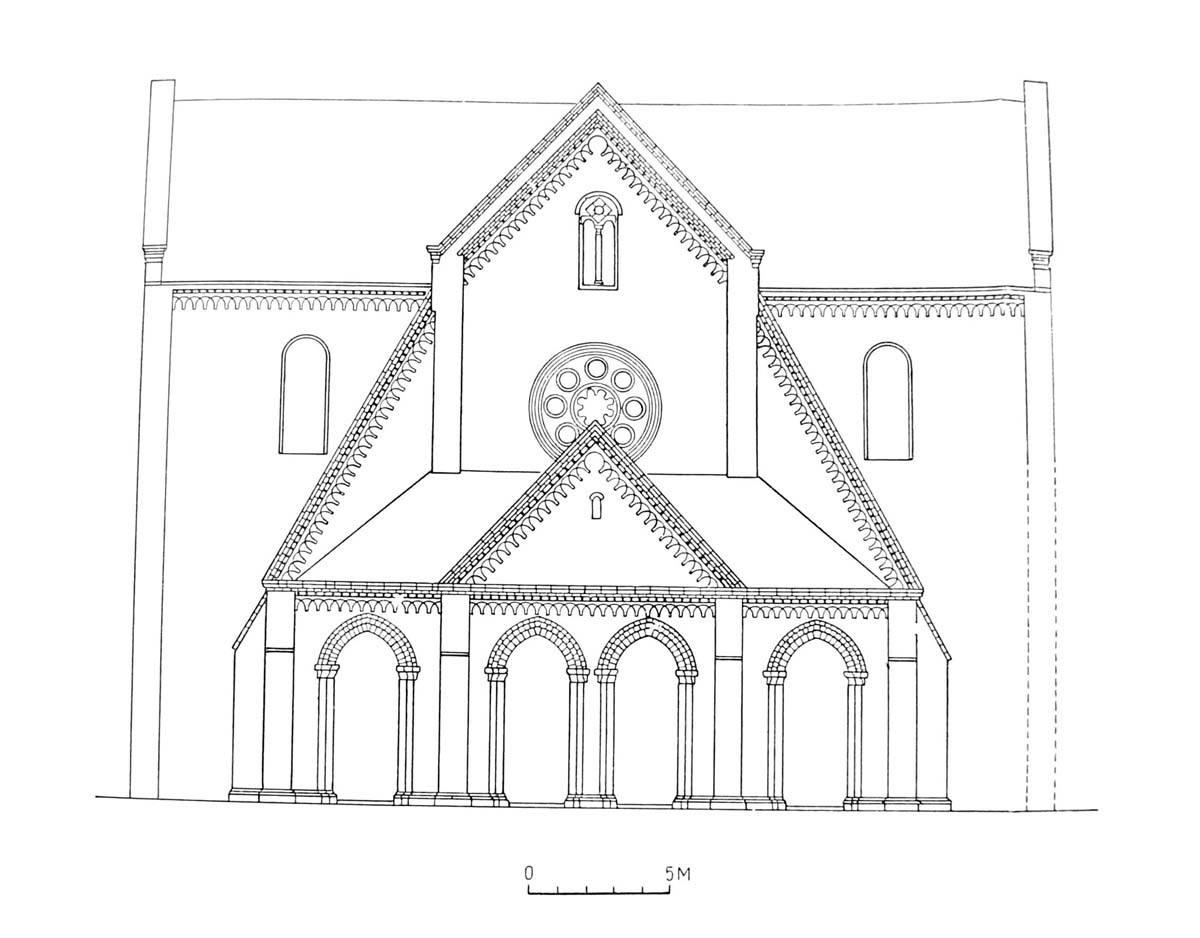

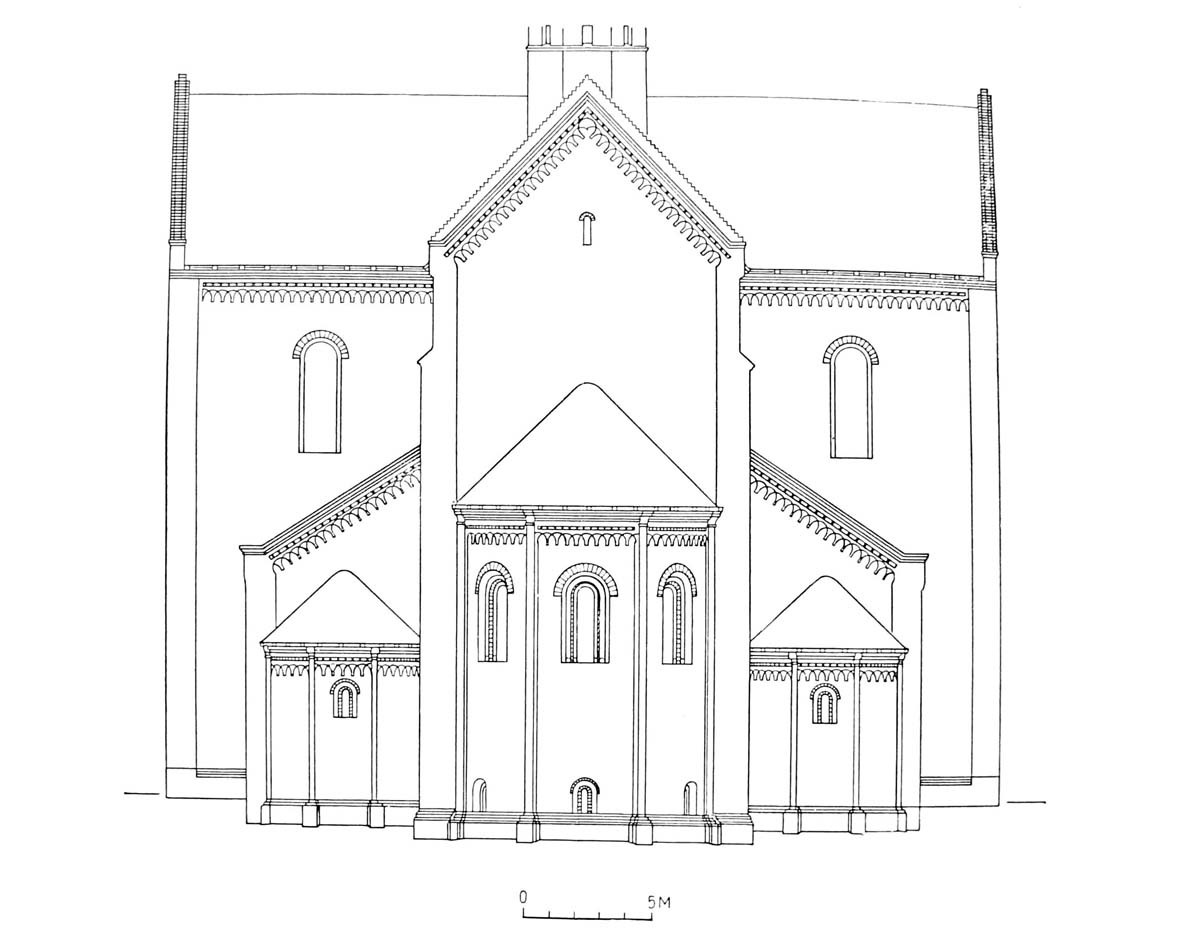

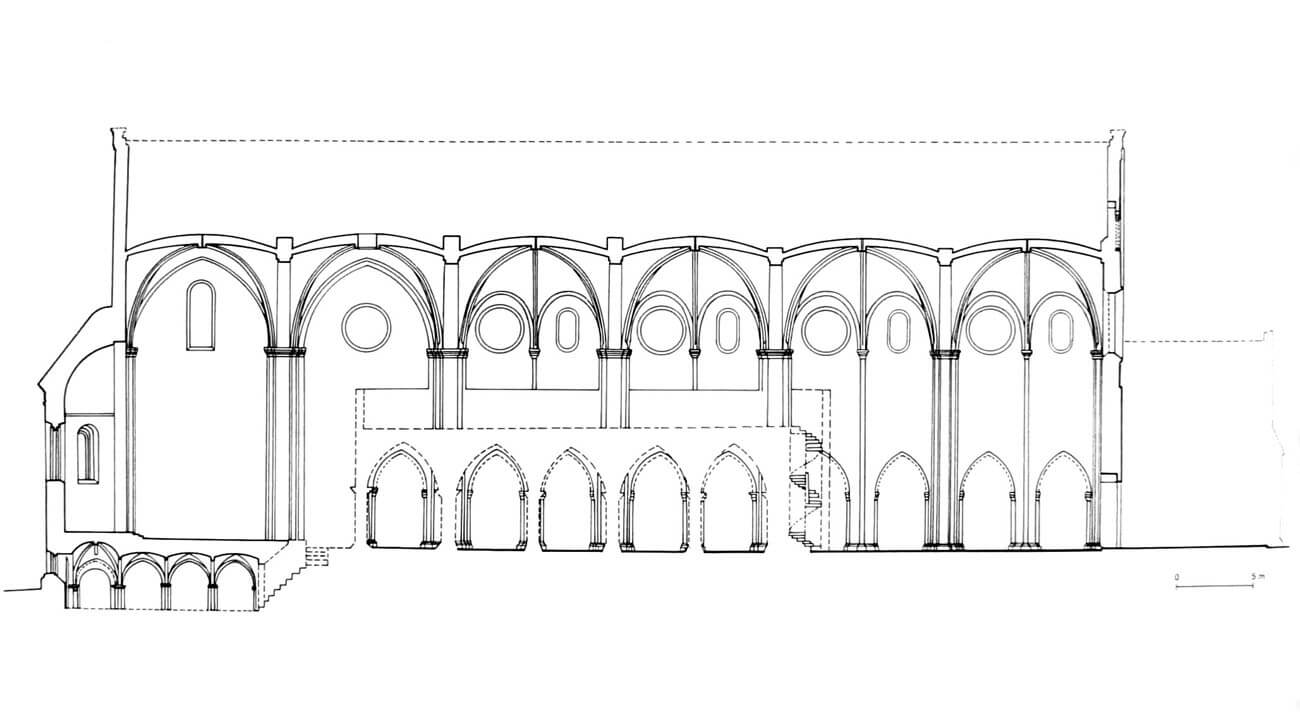

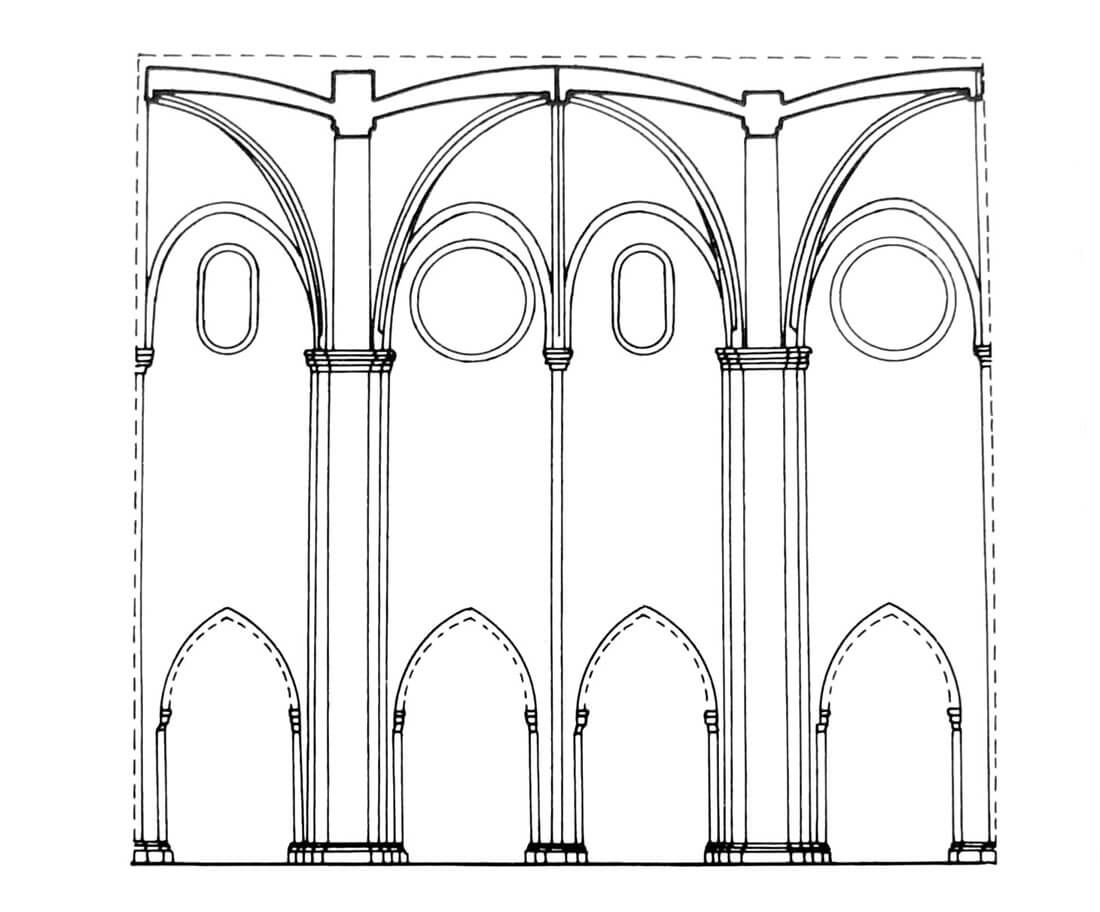

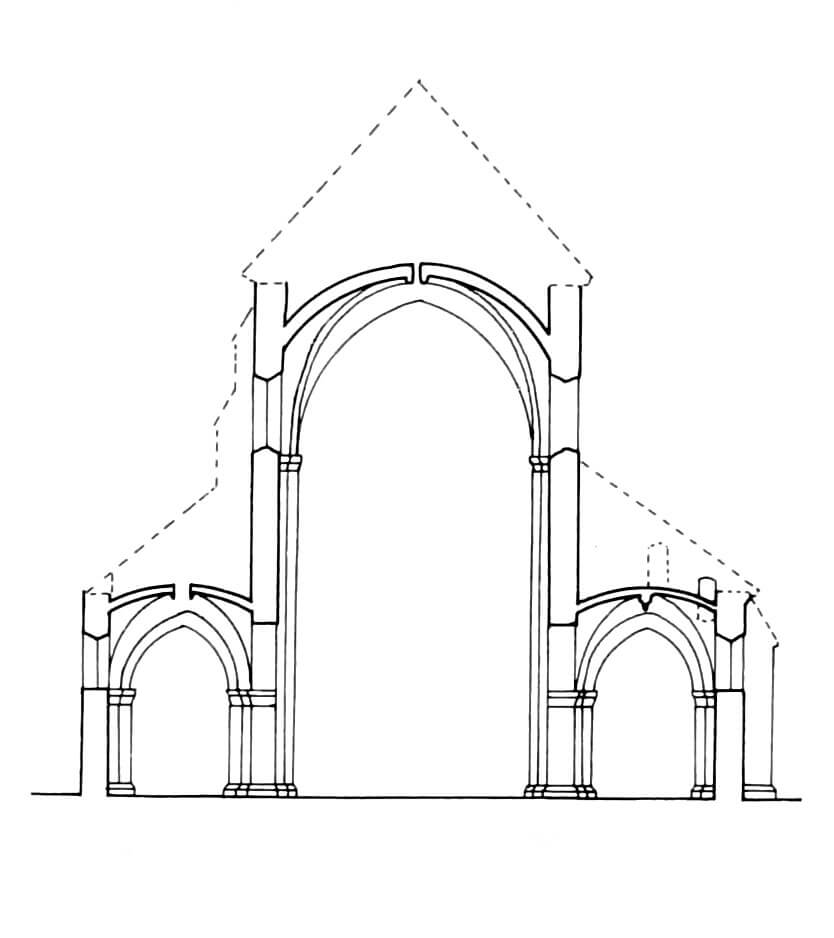

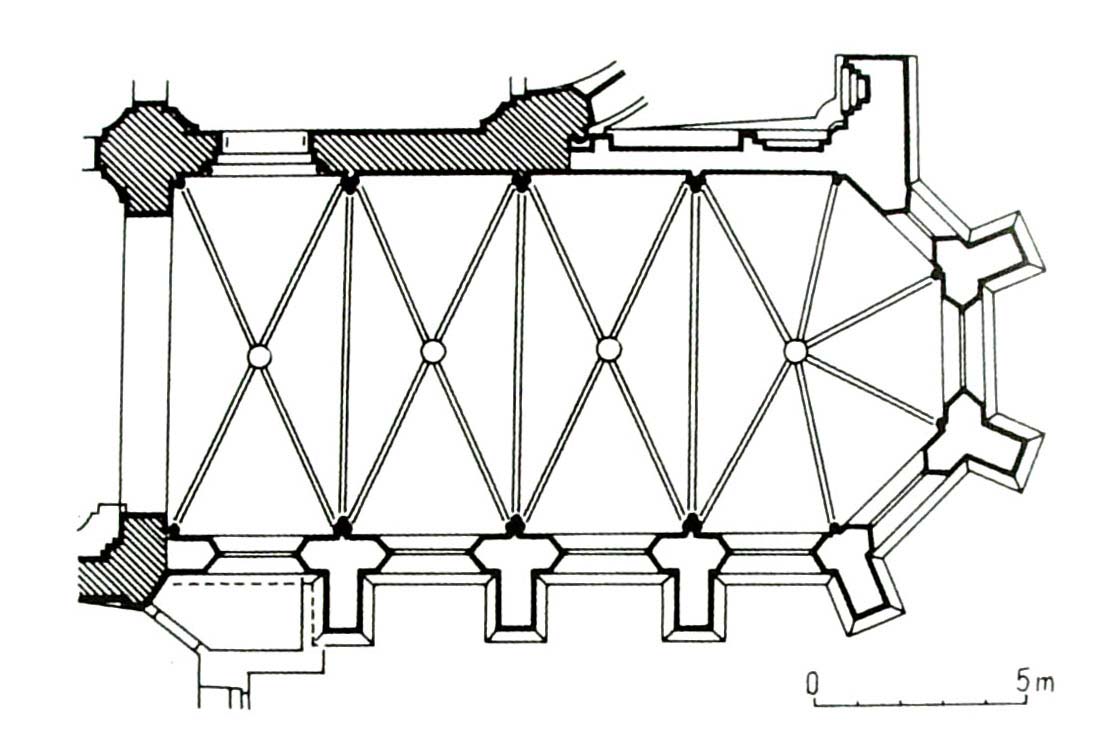

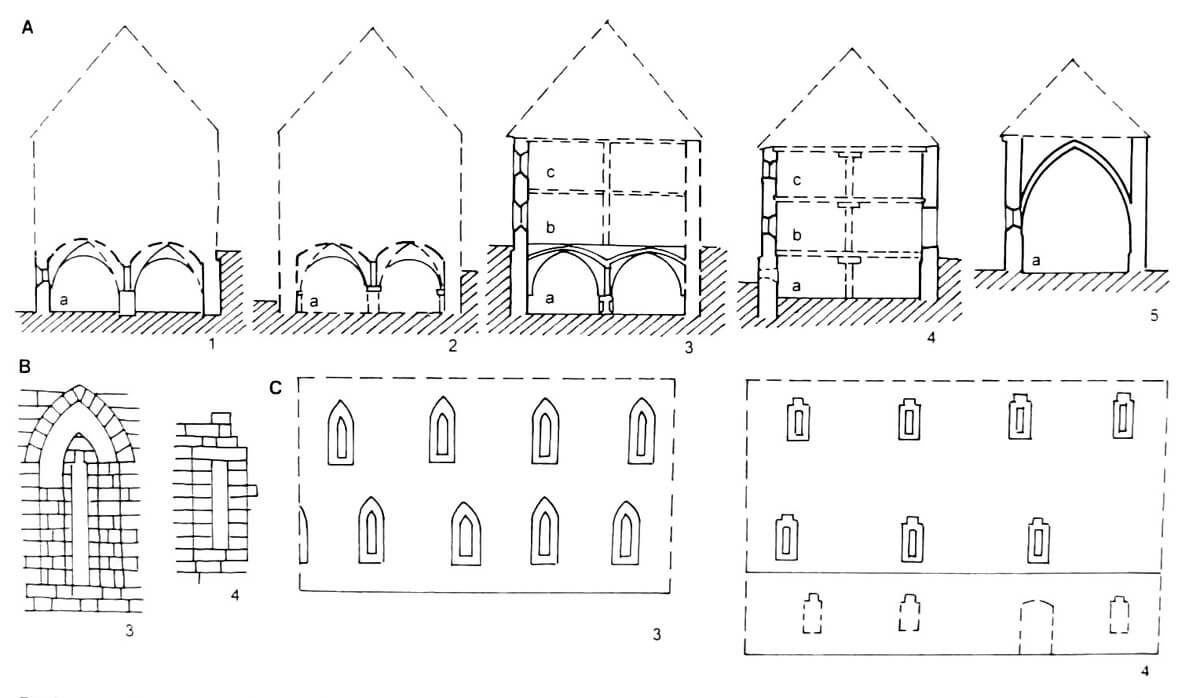

The nunnery and parish church of St. Bartholomew the Apostle and Saint Hedwig was built of bricks in the monk bond, using stones in structural and decorative elements. Originally, it was a three-aisle basilica with a transept, an chancel closed with an apse and two chapels on its sides, and a large arcade porch at the west facade. The outer façades of the church were surrounded by a frieze of interpenetrating arcades, over which a decorative strip of oblique bricks ran. The same frieze was framed the gables which edges were made of stone ashlar. The interior of the central nave was alternately lit by round and elliptical windows, and the walls were supported from the north by impressive buttresses reaching above the aisles. The northern facade of the aisle was divided into two parts. The western fragment was founded on a moulded pedestal and divided with buttresses, while the eastern part did not have a pedestal, and the wall was divided with buttresses and pilaster strips. The west facade of the church was topped with a triangular gable, which was continued by impressive buttresses reaching the walls of the aisles. The gable was pierced with a two-light window and below with a round rosette.

Inside the church, a rib vaults were used. The interior of the chancel received dimensions 7.9 x 9 meters, transept 29.1 x 8.9 meters, the central nave width 9 meters, and the aisles 4.5 meters wide. The whole church (without the porch) was 62 meters long. Its last element erected in the Middle Ages was a high west tower, adjacent to the northern aisle and placed at the west portal. It was crowned with a hip roof, below which window openings and arcades in the ground floor were pierced.

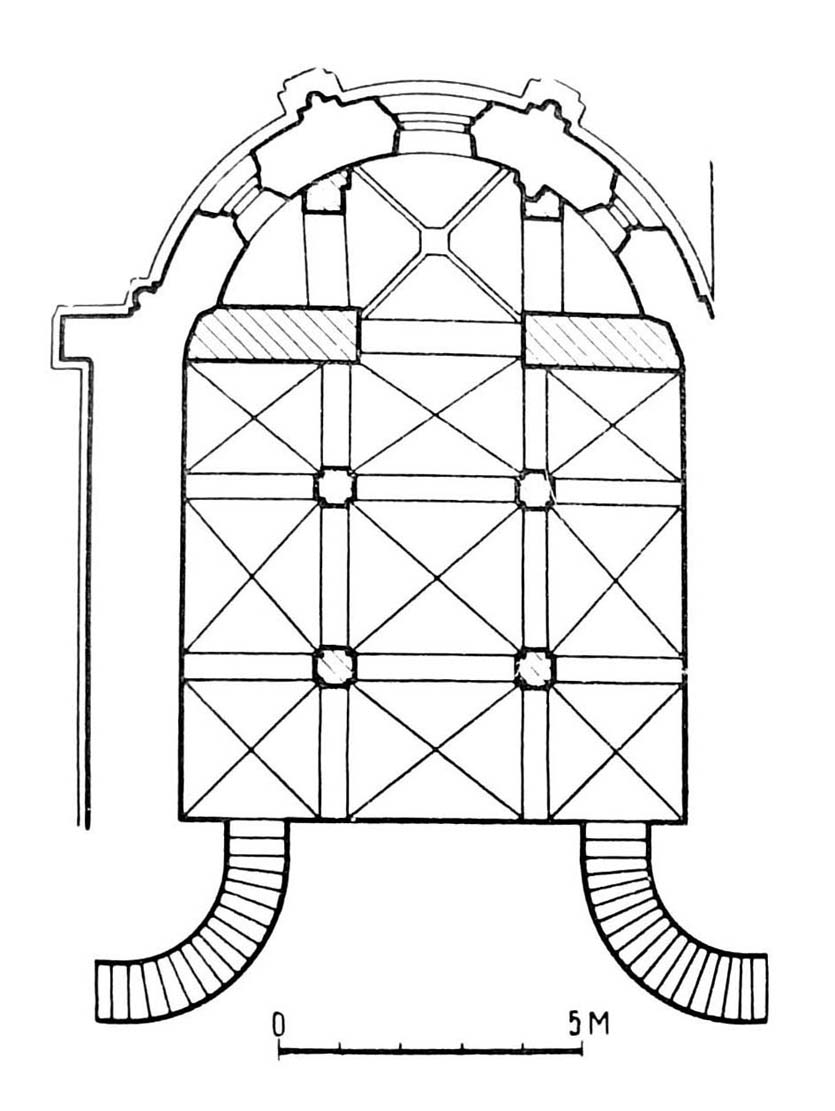

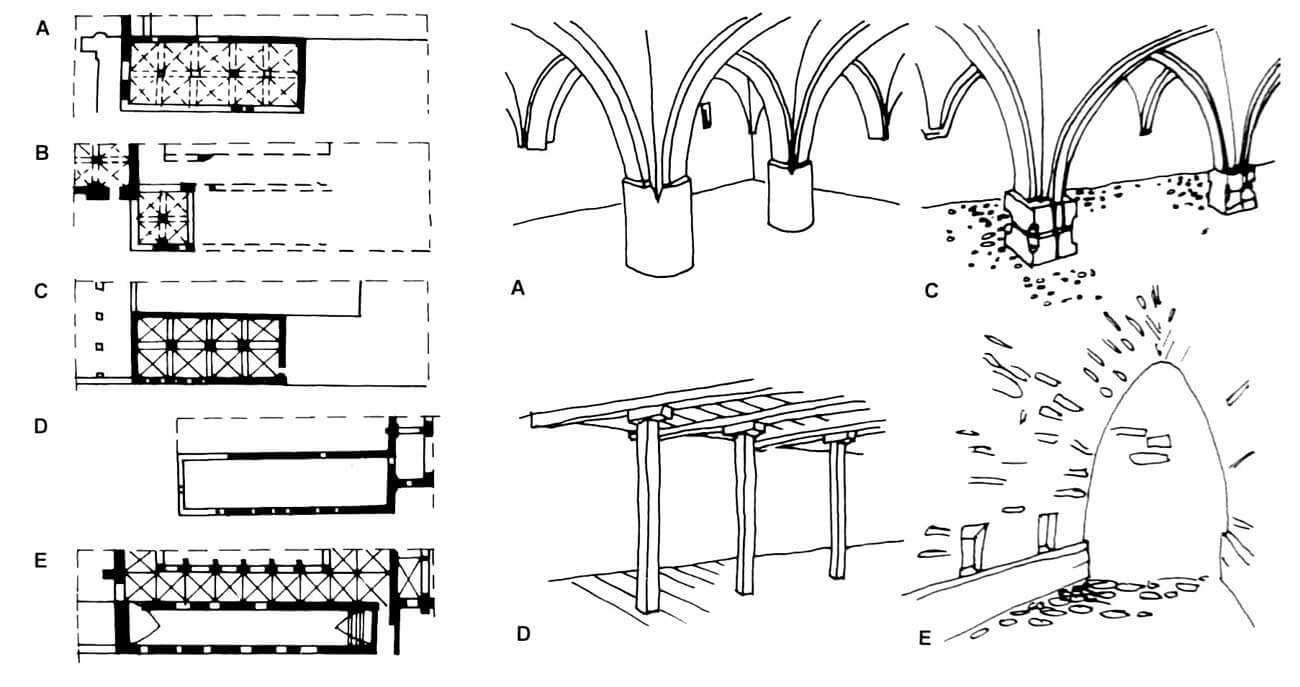

Unique in Cistercian architecture was the three-aisle crypt under the chancel and the matroneum (gallery) of nuns, built not as usual in the western part, but in two eastern bays of the central nave and extending up to middle of the transept. A round staircase located in the middle of the central nave led to the gallery, and from the gallery, one could also go to the rooms of the first floor of eastern range. The construction of the crypt was structurally justified, as the area fell from west to east, reaching a height difference of around 2.7 meters at the apse. Its creation probably resulted partly from the desire to level utility floors in the church. It was partially embedded in the ground, a three-aisle and three-bay room on a square plan with an apse in the east in which lighting windows were placed. The interior of the crypt was covered with cross vaults, of which only the apse received ribs and a bosses. The vaults were supported on narrow buttresses, brick pillars and columns.

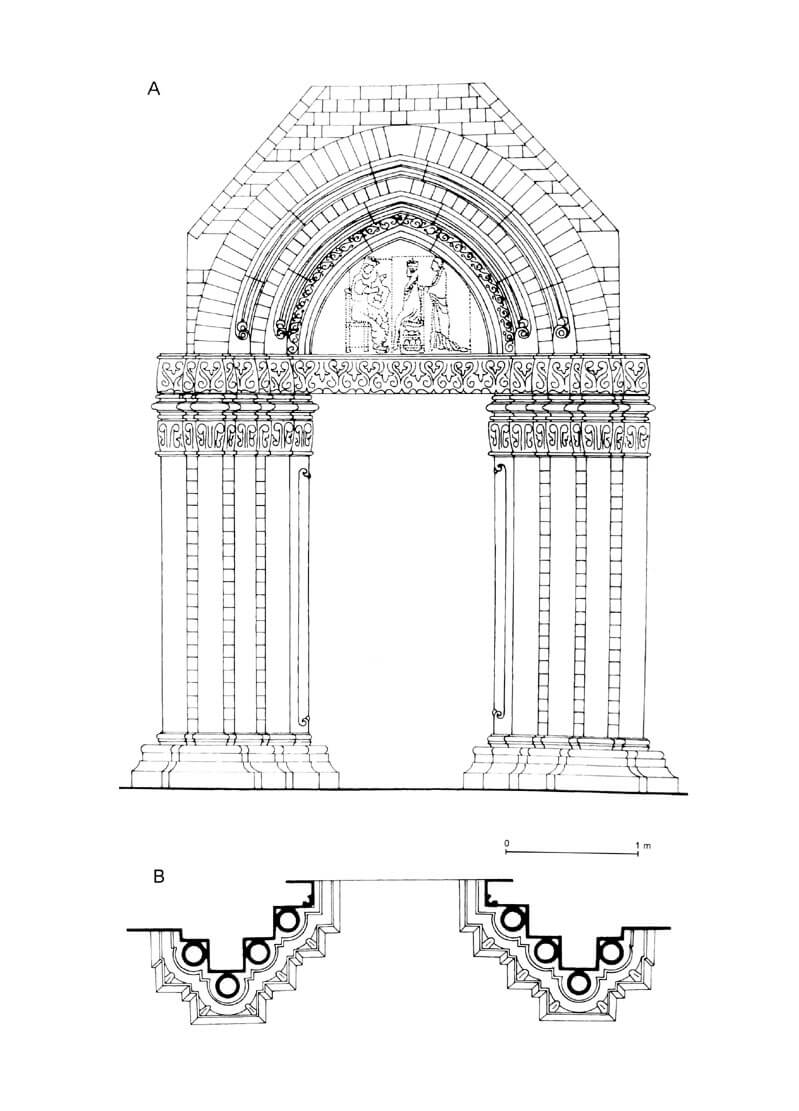

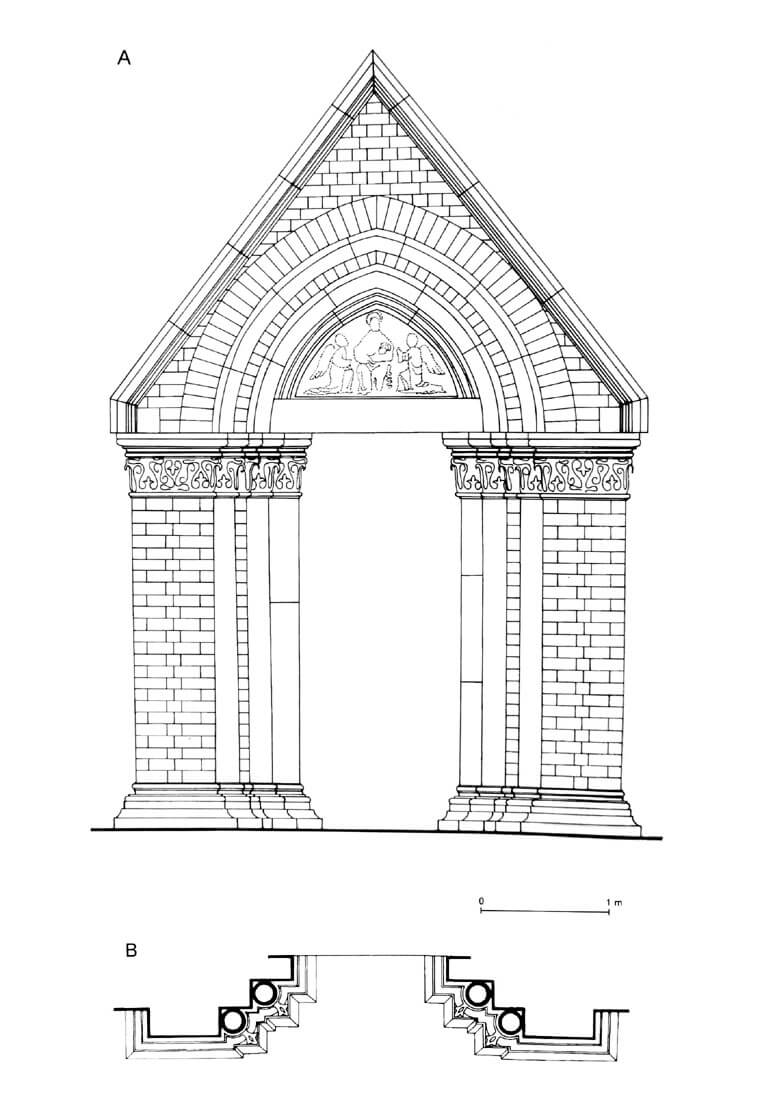

Unique in the church was the richness of late-Romanesque figural sculpture used in it. Three western portals, the main entrances to the temple, stood out from the outside. The most decorative element in the nave were column’s bases with the so-called crockets of various forms: some resembled animals, others resembled leaves of plants. The chalice heads of columns, as well as the cube and chalice-cube heads of the wall shafts, on which the vaulted ribs were supported, had a simple form, although in the chancel they were covered with decorations of animal and vegetable forms. Similar ornaments were used on the bosses of the aisles, while the simple forms had the bosses of the central nave and transept vaults. The walls of the church were originally brick with white joints, not covered with plasters. On the other hand, the details were polychrome, painted in red, blue and white. The floors were also multi-colored, laid out of ceramic, small, smooth tiles of geometric forms and square tiles decorated with convex ornaments in the form of plaits, griffins, dragons or centaurs, coated with yellow, brown and green glaze.

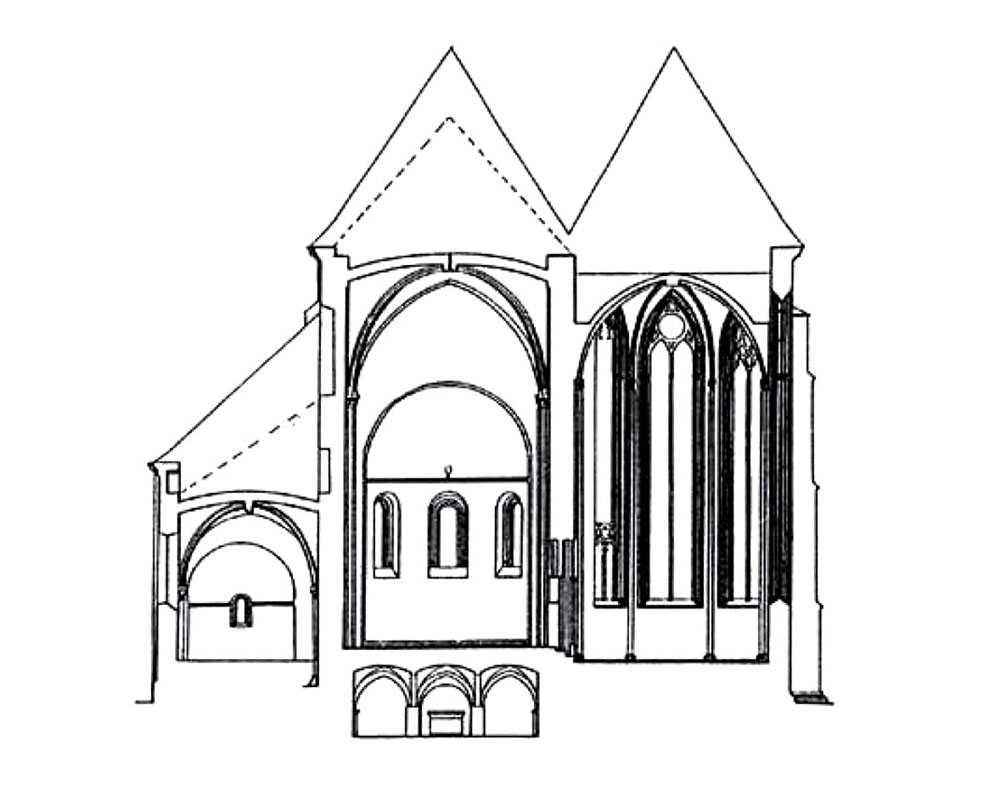

In the eastern part of the church, on the southern side of the chancel, there was a three-bay chapel of St. Hedwig built, the first building in the Polish lands erected entirely in the Gothic style. It transplanted many French solutions to Silesia, including the local variety of the “glass cage”, i.e. buildings with walls dematerialized by large tracery windows. During its erection, it was planned to expand the chancel of the church, which is why the binding of the future eastern wall of the chancel was built and windows were made in the northern wall of the chapel. The expansion finally never took place and the windows were bricked up.

St. Hedwig’s Chapel was built on the plan of an elongated rectangle, the walls of which were fastened with buttresses and a plinth with a moulded cornice. The external elements of the chapel were not plastered. The redness of the bricks was accompanied by the whiteness of specially painted joints, and the arcade frieze under the eaves had a similar color scheme. Because a cross-rib vault was built inside, and there was a rib beetween each bay, all the wall-shafts on the longer walls were placed in bundles of three, while single-shafts were created in the corners. The shafts were placed on octagonal pedestals with moulded bases, and they were also equipped with capitals with floral decorations. The windows were framed with columns with chalice-shaped capitals. In the center of the chapel the tomb of St. Hedwig was placed, originally stone, covered with a wooden canopy. In the southern wall there were two- and three-arcade niches for sedilia in red sandstone frames crowned with trefoils. The entrance to the chapel led from a chancel, by a stone, moulded portal with columns in the jambs and bas-relief leaves of ivy, oak and vines.

On the southern side, the church was adjoined by claustrum buildings. They consisted of three wings arranged around a square inner patio with a cloister. We only know that in the west wing at the basement level there was a cellar (pantry, warehouse), topped with a cross vault without ribs and set on narrow arch bands, wall pilasters and a massive pillar made of sandstone. The brick walls were not originally covered with plaster, while the vaults were probably whitewashed. The oldest floor of the cellarium was built in the form of a raw clay concave, supplemented with brick bands at the pillar and perimeter walls. Above must have been located the rooms intended for lay brothers – the refectory where they ate and the fraternity where they worked, especially in the winter. The upper floor probably housed a dormitory of lay brothers, which was probably illuminated only by narrow slit windows to maintain a tolerable temperature in an unheated room. Initially, it could have been one common room, later in the Middle Ages separated by wooden partition walls separating individual sleeping cells.

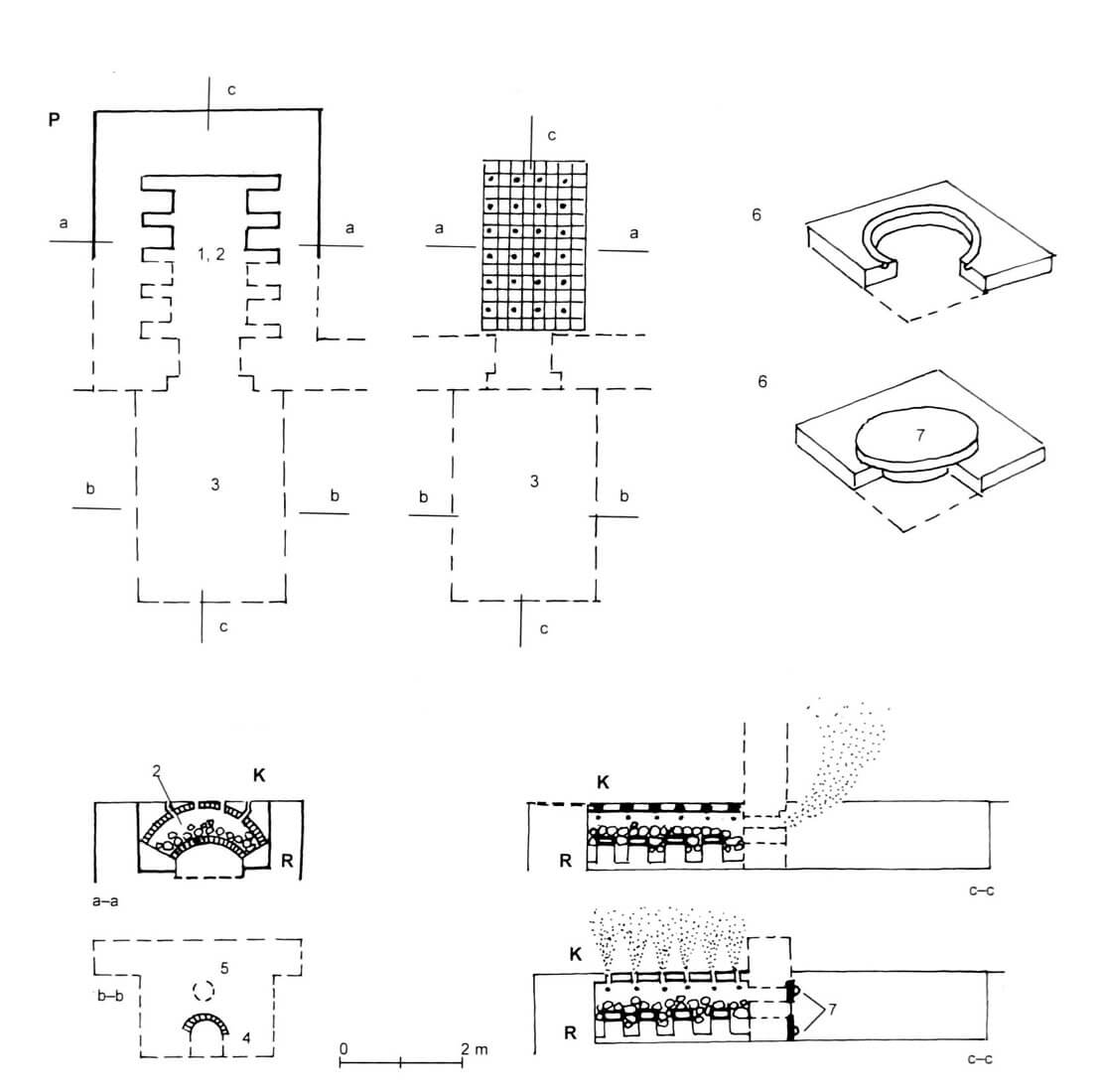

The southern wing housed a calefactory with a hypocaustum type furnace, which was the only one warmed place in the nunnery during the winter, which provide heat by the air supplied through channels in the floor. Fuel for the furnace was supplied from a recess located outside, next to the building wall. Under the floor of the room, below, there was a fireplace with a grate in the form of brick arches. Above it was a heating chamber, partly filled with stones and covered with a barrel vault, in which holes of channels leading to holes in the floor tiles were made. When the fuel was burned in the furnace, the smoke escaped through a channel located in the ventilation hole, and the holes in the floor were closed with ceramic tiles. After heating the stones, the flames were extinguished, the inlet to the hearth and the ventilation holes were covered, and the covers in the floor were removed so that heated air would flow into the room. The calefactory was probably a multi-bay room covered with vaults supported on columns. A refectory and a magnificent kitchen with a double hearth stove adjoined it from the west.

It can be assumed that in the east wing there was a chapter house and a dormitory on the upper floor. The appearance of these rooms is not known, but the chapter houses were one of the most exquisitely decorated rooms in their monasteries. It was there that the brothers gathered every day under the leadership of the abbot, and sitting on the stone benches placed along the walls of the chapter house, they discussed the problems of the convent and conducted courts over the vicious monks. In Cistercian abbeys, chapter houses were also often used to bury deceased abbots. Most often they were adjacent to the sacristies and armaria (chambers for handy book collection) from the side of the church and to the vestibules leading to the nunnery areas outside the enclosure. Fraternities of monks were also placed in the eastern wings, which were most often used as scriptorium, located close to the warming rooms, so that the brothers could warm their fingers frozen while writing. The upper floors of the eastern wings always housed the brothers’ dormitories, connected on one side with the church’s transept to allow access to night prayers and with latrines on the opposite side, which had to be built over special water channels or streams.

Current state

The nunnery church has preserved its original spatial arrangement. The main changes consisted in the demolition of the right chapel at the chancel (replaced by the magnificent Gothic chapel of St. Hedwig) and the demolition of the western porch and medieval tower, replaced by an early modern one. The angle of the roofs over the northern aisle was increased, the original apse vault at the chancel was demolished and its walls were raised. The quadrangular pillars of the crypt come from the 17th or 18th century and replaced the medieval columns or pillars with columns. Unfortunately, due to the Baroque rebuilding, most of the church’s window openings were transformed. Only the windows of the apse and chapel of St. John, some oval windows of the central nave and rosette and slide in the west wall have survived. Inside, the original system of vault supports has been preserved, but is partly covered with Baroque stucco. Fragmentally collapsed vaults have been rebuilt in their former form, although in the northern aisle they lack bosses. From the entrance openings, the northern portal of the transept and one of the western portals have been preserved.

Medieval nunnery buildings were demolished in the early modern period, a new building were erected in their place. Some of the relics of the medieval buildings have been preserved under Baroque plasters and below the present functional levels. A fragment of the cellary with vault and pier, part of the refectory walls and the ground level of kitchen stoves are visible. The greatest treasure of the nunnery and its best-preserved element from the 13th century is the chapel of St. Hedwig.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Jarzewicz J., Kościoły romańskie w Polsce, Kraków 2014.

Łużyniecka E., Architektura klasztorów cysterskich, Wrocław 2002.

Łużyniecka E., Konczewski P., Cellarium z XIII w. w klauzurze dawnego opactwa cysterek w Trzebnicy, “Architectus” 2(46), 2016.

Świechowski Z., Architektura na Śląsku do połowy XIII wieku, Warszawa 1955.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.

Walczak M., Kościoły gotyckie w Polsce, Kraków 2015.