History

The document of the foundation of Toruń was issued by the Teutonic Order in 1233. This privilege guaranteed the townspeople the right to elect each year the vogt, the judge who was the head of the court consisting of seven, and later, after 1312, of twelve judges. A town council was also established, first confirmed in 1251. Initially, the council and the court were separate organs, but at the beginning of the fourteenth century, the council made the judiciary dependent on it and took over all power in the Toruń.

In 1259, on the basis of the privilege of the lieutenant of national master, Gerhard von Hirzberg, issued at the request of the townspeople, a merchant’s house was erected in the Old Town square. Unlike the shambles and stalls, which were the place of sale of guild products and were associated with the local market, the merchant’s house was to be an institution connected with long-distance trade. Its construction was a landmark event for the town, which for a long time was the only one in the Teutonic state to obtain such a privilege. Even cities as large as Kraków or Wrocław only with time bought the market privileges from the hands of a sovereign, while the Toruń merchant house was from the very beginning a municipal institution. The idea of owning a commercial building probably arose under the influence of contacts with Lübeck and Flemish cities, where halls and other market buildings have long been the property of the townspeople. In the new merchant house, rooms for the town authorities have probably also found their place. It is known that the council employed a writer, and the town office already in the thirteenth century received and sent statutes, both general and guild, and kept accounting books. In addition, the town council received significant amounts of money or valuable items for storage (e.g. half a barrel of gold and half a barrel of silver from Władysław Opolczyk).

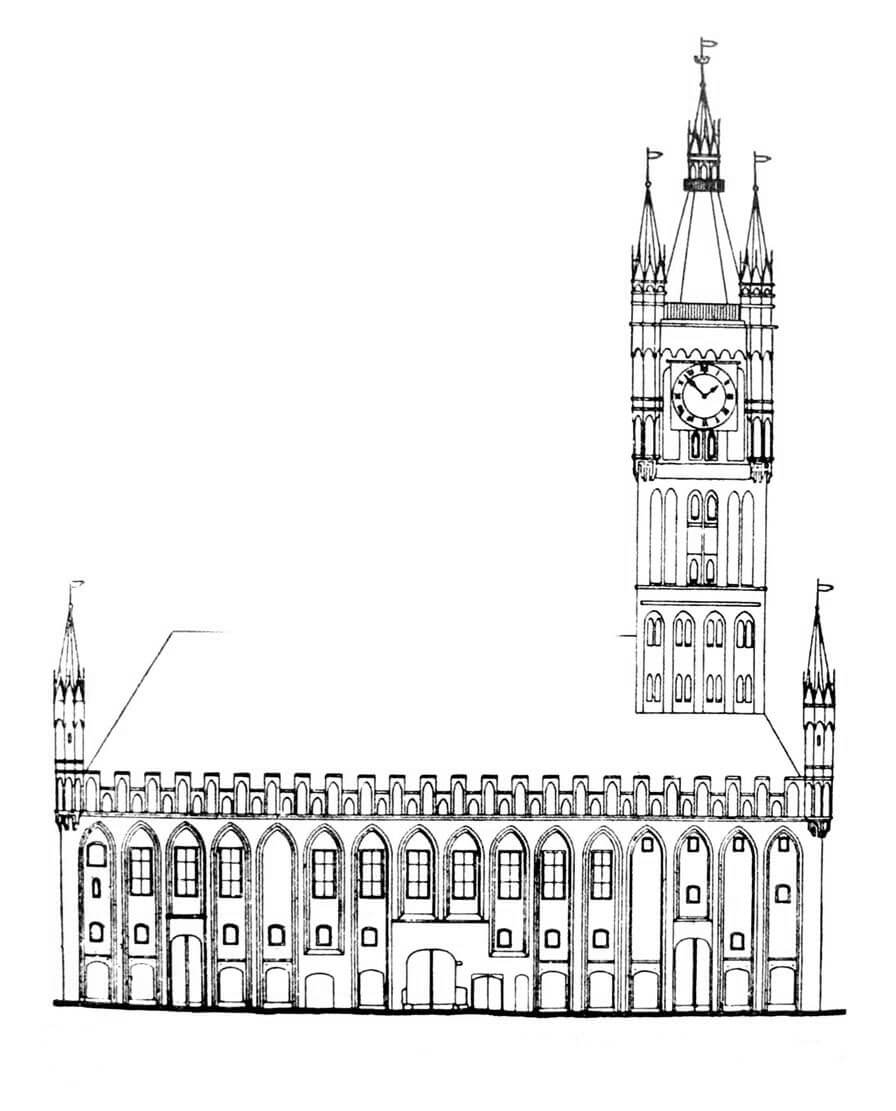

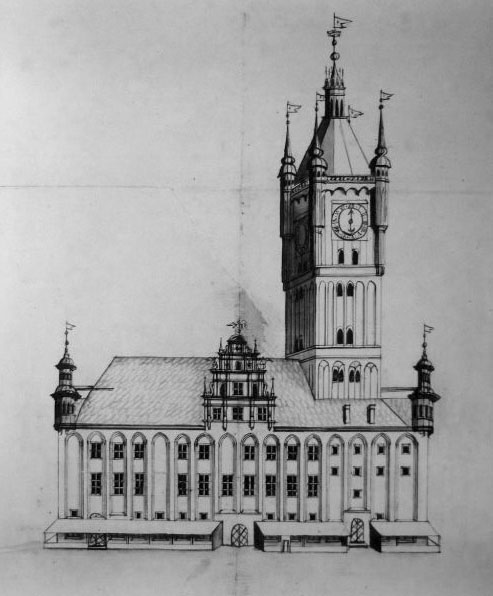

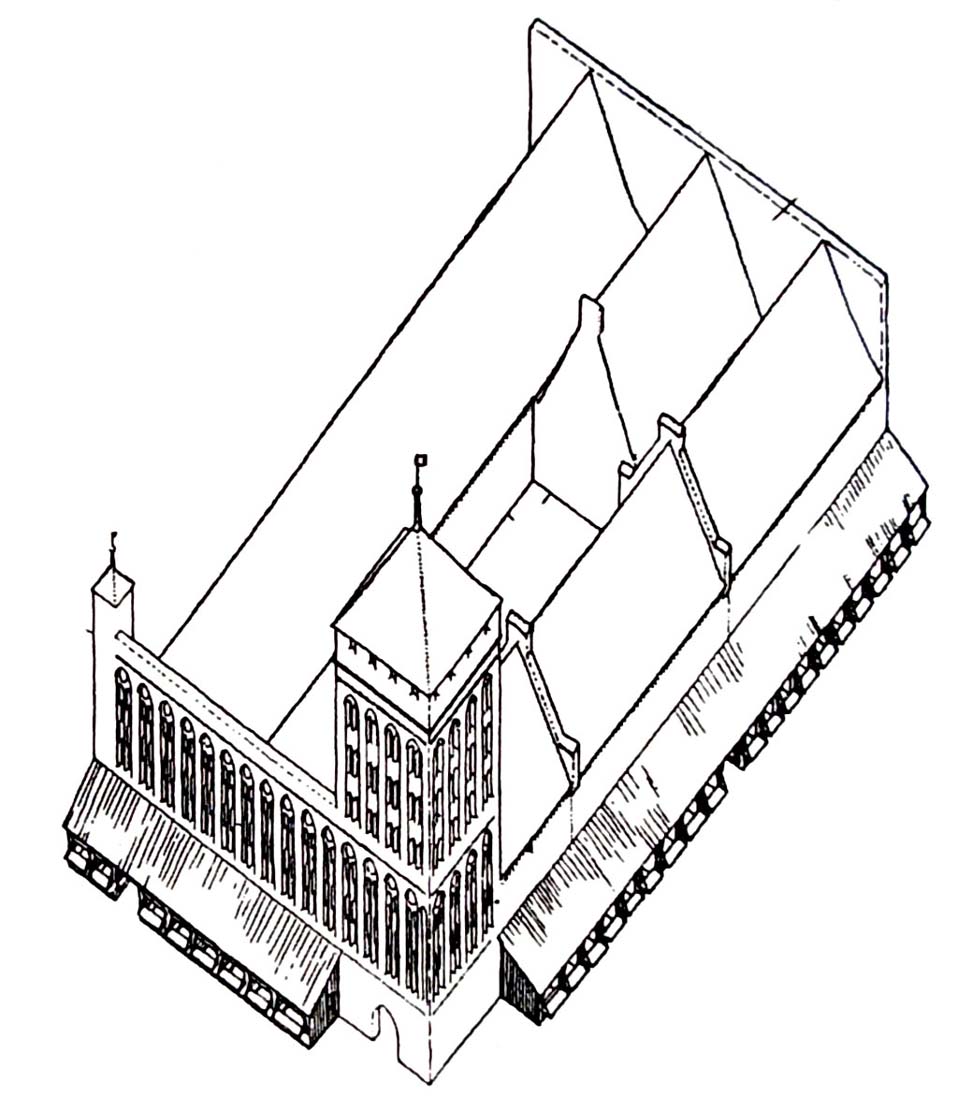

In 1274 Toruń obtained another privilege, this time allowing the construction of bread stalls, during which a tower was also erected. The mid-market buildings thus formed, remained unchanged until the end of the fourteenth century, when due to the poor technical condition of old buildings, supposedly threatening to collapse, a great expansion of the merchant house was carried out. It took place in the years 1391-1399, at the height of the development of medieval Toruń, probably under the direction of the Polish town builder, master Andrew (Andris), on the basis of the privilege of the Teutonic Grand Master Konrad von Wallenrode from 1393. At that time, old commercial buildings were demolished, leaving only the tower, and the administrative, commercial and judicial functions were combined in one building, which was a solution not often found in Europe at that time. The town hall gained the shape of a four-wing building on a rectangular plan with an internal courtyard.

In the years 1602-1605, on the initiative of the mayor Henryk Stroband, a mannerist reconstruction was carried out, consisted in raising the building by one floor. It did not erode the Gothic character of the town hall, as the architect extended the Gothic arches with pointed bows. Instead, it introduced new elements such as cornered overhanging turrets and gables in the middle of each wing.

In 1703, during the siege of the town by the Swedish army, there was a serious fire in the town hall. As a result, almost all interior decorations were destroyed, the gables collapsed, and the building until 1722 was left without a roof. In the years 1722-1737 reconstruction was performed. New gables were erected, interiors reconstructed, and from the west avant-corps was added of the late Baroque forms. In 1869 it was replaced by the surviving neo-Gothic one. In the 19th century, some interiors were remodeled.

In the years 1957-1964 a general renovation and adaptation of the museum was carried out. The most important work was to strengthen the walls and vaults, restore the interiors of the old appearance by demolishing partition walls from the nineteenth century, and uncover some of the medieval architectural elements that were being bricked up later.

Architecture

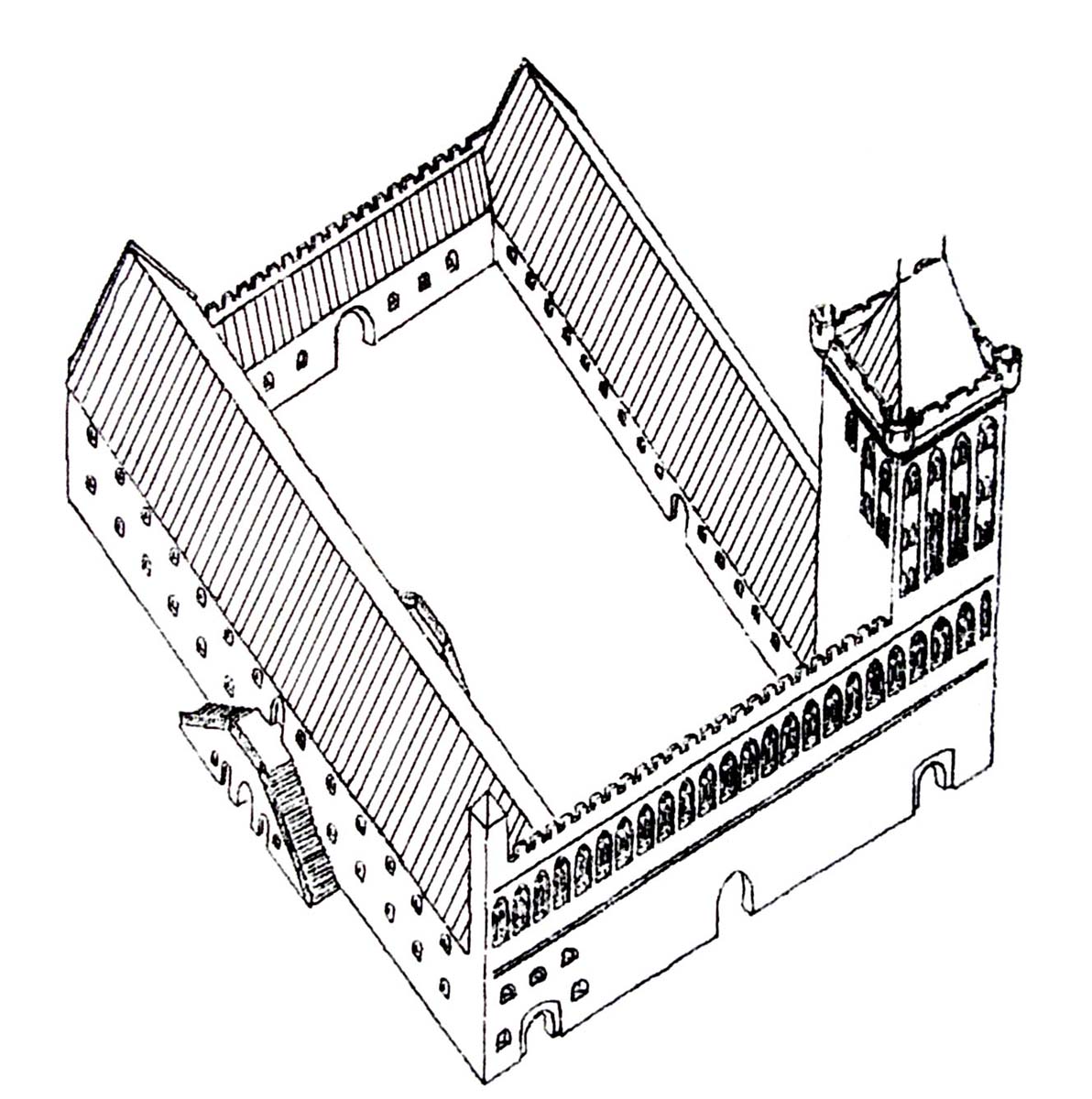

At the end of the 13th century, the buildings of the Old Town square consisted of two elongated, parallel buildings. From the west there was a two-story merchant house used by the trade patriciate, and from the east a building containing bread stalls. The gable walls of both buildings were connected by a screen wall, while a tower adjoined the stalls from the south. In addition, in the northern part of the market buildings, between the cloth hall and stalls, there was a one-story and brick house of the court and near the north-west corner of the cloth hall there was a building of the weight in which various goods were weighed. The whole complex was probably surrounded by one-story buildings used by smaller merchants. They were probably timber, with mono pitched roofs and had their counters lowered outside.

The merchant’s house was built on a rectangular square with dimensions of 9 x 45 meters. It had two floors, with the stairs probably leading to the upper floor, similar to those used in other medieval market halls. They were probably halfway across the building and connected to the hall entrances. They could have consisted of two flights of steps leading to a common platform on the first floor level, which was also used to read town council announcements. In this case, they had to be turned to the west, broader side of the market, where townspeople gathered. Under the platform was the entrance to the ground floor of the building, and on the sides, under the stairs, rooms intended for the town residents. Another similar staircase was probably from the courtyard side. The interior of the merchant’s house was probably a large hall with a wooden ceiling supported on a row of poles. There must have been separate chambers for merchants, confirmed in written sources from 1330. On the first floor, at one end of the hall, there were probably rooms of the town council.

Bread stalls stood on the eastern side of the merchant’s house, on the plan of an elongated rectangle. Probably it was a brick one-storey building, because no medieval record mentions stairs and rooms above the stalls. Inside it housed a long hall covered with a wooden ceiling, supported on one row of poles. The building probably had four entrances located halfway along each side. The southern entrance led to a four-sided tower.

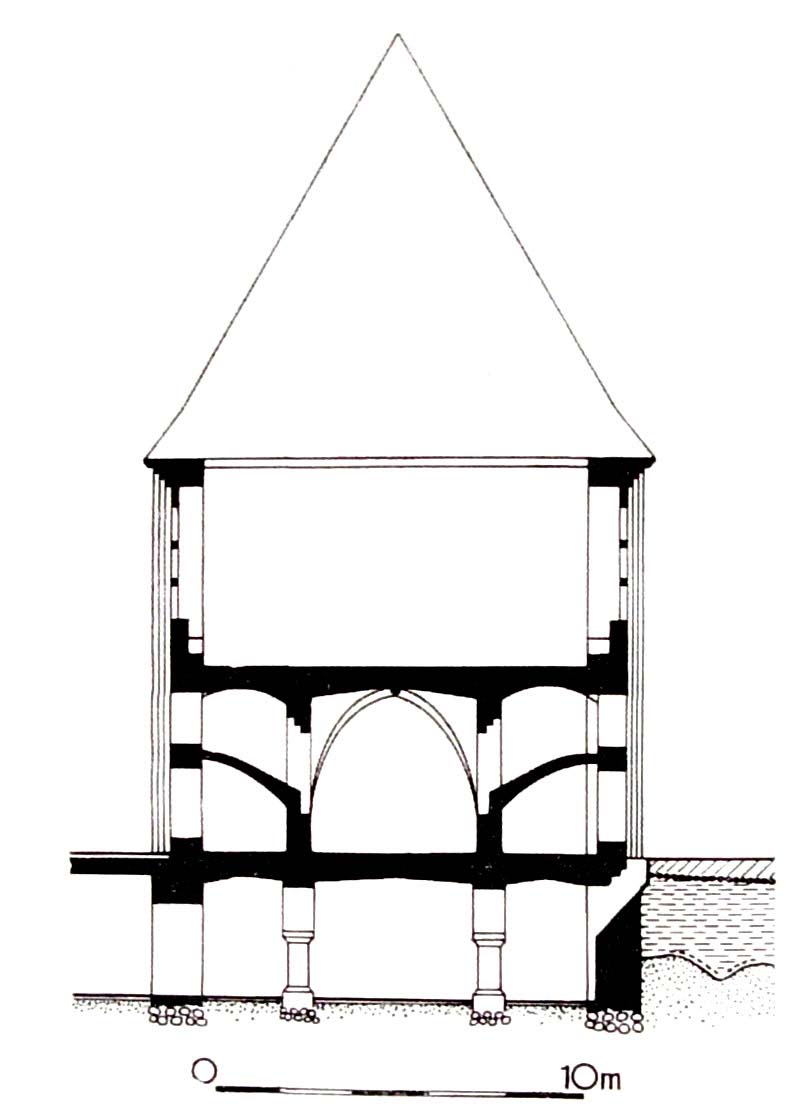

The town hall tower was erected in the south-eastern corner of the market square, at the intersection of the two most important roads of the Old Town. It was built on a square plan with a side of 7.7 meters and in the 13th century it was about 23 meters high. Its ground floor served as a passage to stalls, which is why large entrance openings were pierced in the southern and northern façades. In the eastern and western walls, there were three deep niches with stone seats perpendicular to each other, but they were bricked up probably due to the tower being raised in 1385. At that time, a cross vault was founded on the ground floor, which replaced the original wooden ceiling at a height of 2.7 meters. Below there was a barrel vaulted cellar, to which the entrance led directly from the market square on steep stone steps. The southern wall of the upper part of the tower was divided by four high panels in which small, twin pointed arches (some with windows) were placed on four floors. The eastern wall received similar fragmentation, with the difference that the arcade frieze does not pass through it, while the northern and western facades, as less important and less visible, were developed with less decoration. It is not known what the original top of the tower was. It can only be assumed that, following the model of Flemish beffroi, it had a porch with a battlement, circular bartizans in the corners and was covered with a hip roof. The faces of the outer walls of the tower were painted in red, and the arcades of the frieze were decorated with painting ornaments in tracery patterns in white and black.

A screen wall was connected to the tower, probably modeled on a similar building from Lübeck (although it was not connected to the tower there). It was a monumental, large and smooth surface, decorated with a row of pointed arches. The reason for its creation were solely aesthetic and representative, namely the creation of a screen for a group of market buildings. Its orientation to the south, towards the sun, certainly increased its artistic value.

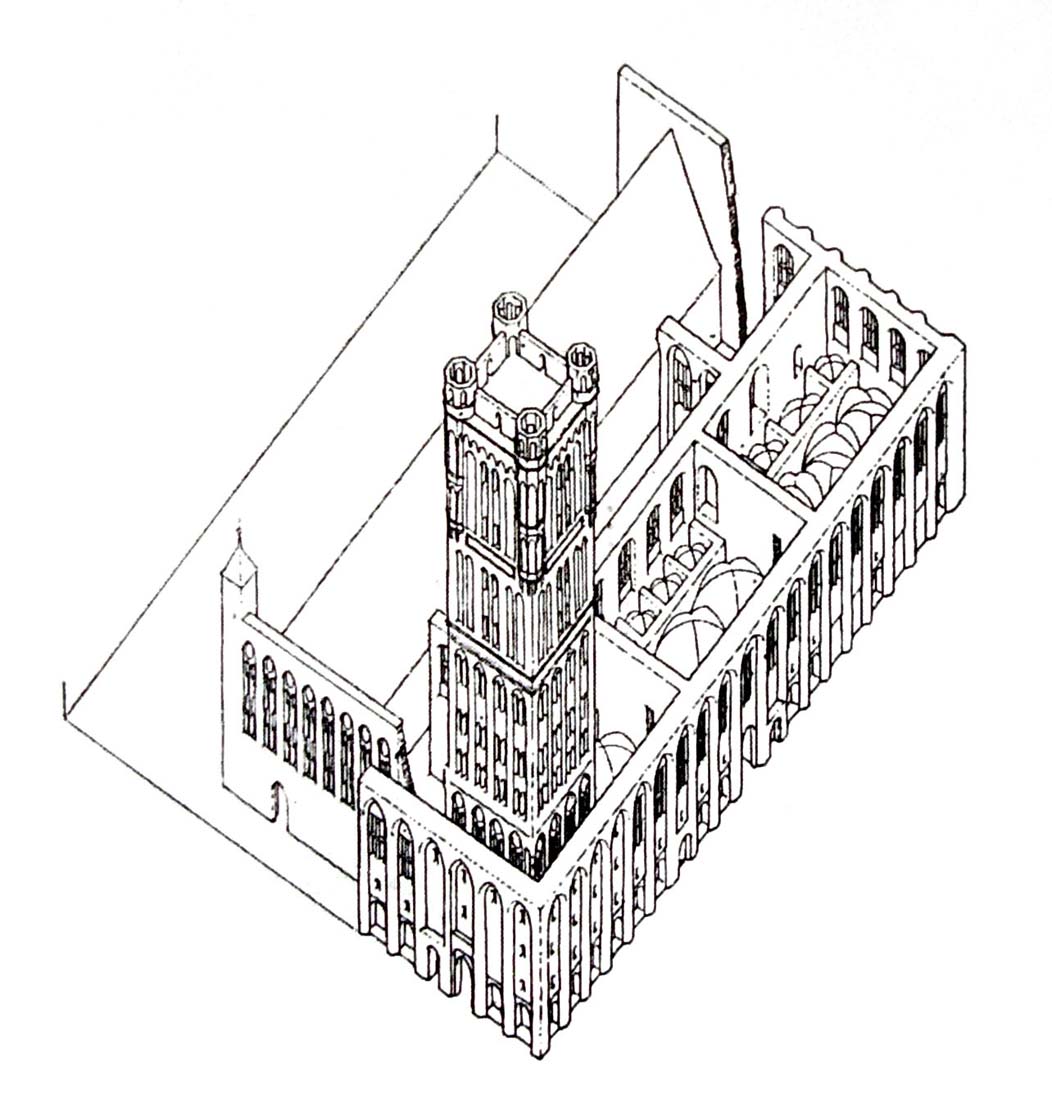

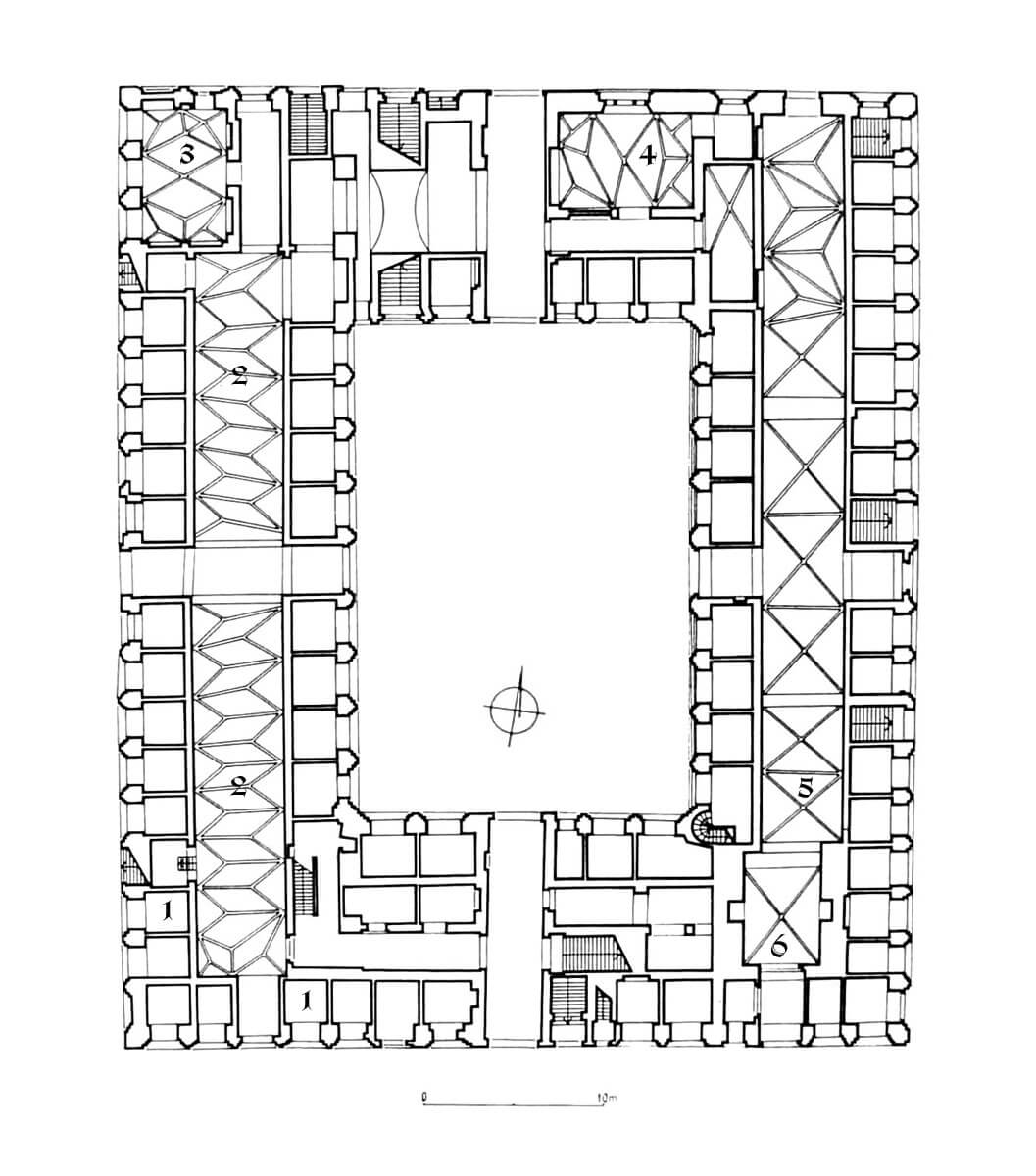

In 1391, the old buildings were partially demolished except for the tower to create a quadrangular complex in their place, measuring about 44×52 meters with an internal courtyard and a quadrilateral tower at the confluence of the southern and eastern wings. The large façades were divided by the rhythm of vertical recesses, both from the courtyard and the market sides, which gave the building a high uniformity. All the niches ran through the entire height of the facade, except for those that housed basement entrances and gates. Placing window on three levels allowed the use of different sizes of openings. The whole building obtained a compact form, probably not by accident similar to the commandry castles of the Teutonic Order.

All wings and the town hall’s courtyard had a basement. Under the east wing, the chambers were divided into three routes with a wider central route, and their vaults were supported by massive stone columns. Under the courtyard, two routes were created, separated from each other by a space without a basement and adjacent to the west and east wings. Each contained four rooms with a square-like plan, topped with barrel vaults. Wine was stored in the cellars, but most of all, it was wine and beer were drunk there (in the Gdańsk Cellar recorded since 1549). The basement chambers were named according to their location (e.g. “near the weight”, “under the weight”, “under the tower”), according to the emblems above the entrances (“under the lion”, “under roosters”, “under the dragon”) or by surnames or tenants’ names (“Hugh’s basement near the weight”).

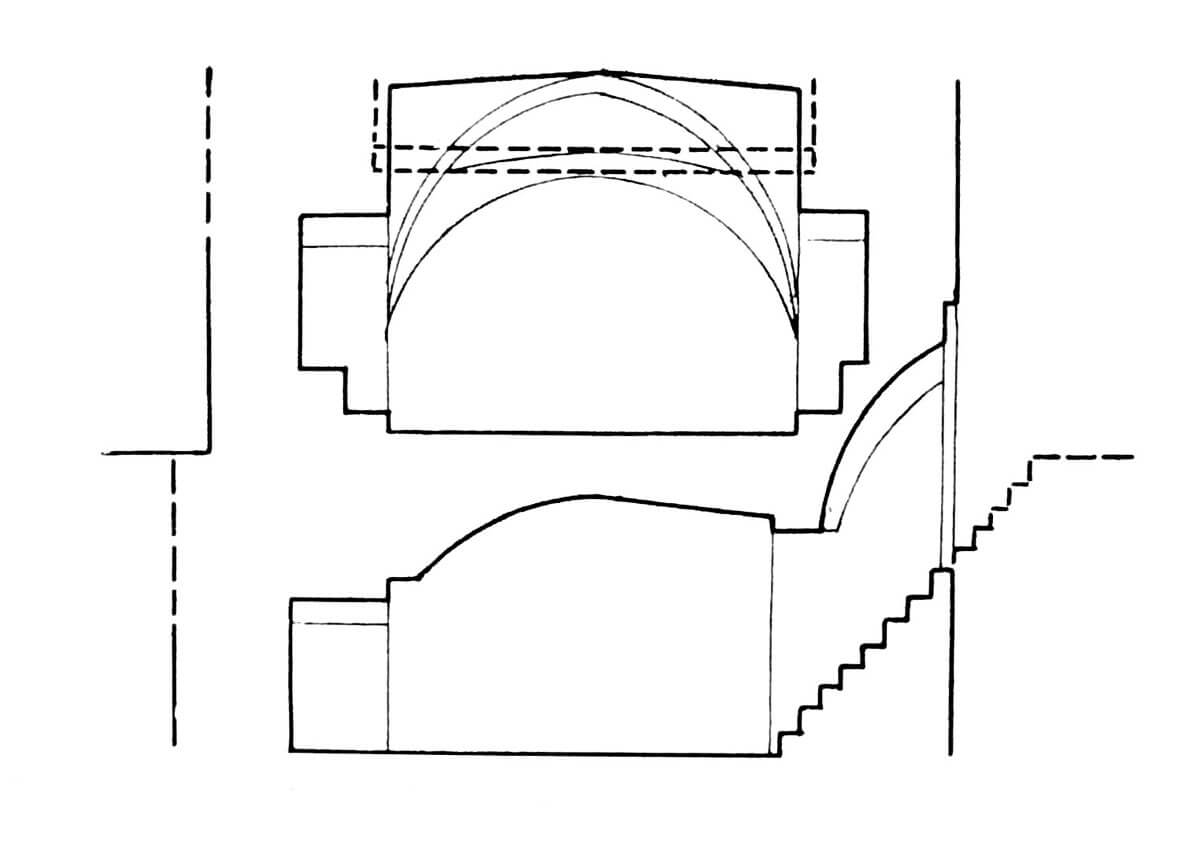

The ground floor was a great market hall. In the east and west wing, the vaulted halls served rich merchants, while the stalls for poorer merchants were along the halls, accessible only from the outside. In the middle of each wing there were wide passages to the courtyard, of which perhaps north and south were intended for wagons, and the rest for pedestrians. The east and west wings housed long halls, the first for stalls, the second for the cloth hall. The western hall was shortened from the north for the weigh room (available directly from the market from the north), while the eastern hall connected with the passage under the tower. The northern wing was a courtroom, open to three sides so that hearings could be heard. Behind it, from the east side was the chamber in which the court meetings were held, and next to the pre-trial detention in a stall adapted for this purpose from the courtyard side. The ground floor yet contained a small chamber in the south wing, between the passage and the cloth hall, accessible only from the gate side. Its purpose is unknown, but it probably was not related to trade. All rooms on the ground floor were vaulted. Bread stalls and the cloth hall had cross-rib vaults, weight and court rooms have rib, three-support vaults. The free flow of people was ensured by entrances from both ends (from the north and south), as well as passages in the middle of the building leading to the courtyard. Around from outside and from the courtyard, the ground floor of the town hall was surrounded by the aforementioned row of stalls – low, separated rooms, accessible only through large openings in the external walls. The window sill of these openings also served as a counter for spreading goods. At night, the stalls were closed with lowered timber shutters, which on the day after being lifted, formed a roof protecting against sun and rain. This arrangement of the stalls complicated the lighting of the inner halls of the town hall, which was solved by placing a window over each stall.

The first floor became the seat of the town council and its offices. The largest room on the first floor, located in the west wing the Great Burgher Hall (Long Hall), was the site of important urban events. Kings were met in it, and also the parliaments of the Royal Prussia took place here. Clothiers used the hall on weekdays, and from the beginning of the 16th century the council held elections in it. Its original lighting was provided by two rows of openings arranged on two levels. The lower row was formed by small, narrow openings located at the height of the window sill, above which there were highly pierced proper windows. Probably the Great Burgher Hall did not have a ceiling, but an open roof truss, as did the cloth hall in Bruges and Ypres. In the east wing, rooms of the town administration, e.g. the chancellery, cash registers, were situated, all covered with ceilings. The windows that lit them originally had brick seats inside the window niches. Vertical communication was provided by staircases located in the southern and northern wing, a narrow staircase at the southeast corner also directly connected the first floor with the basement. The tower, raised in 1385 by two floors, served as a watchtower, and the bells hung in it called councilors to meetings. The tower also had a clock, which was already repaired in 1415 and 1417. The added part of the tower was decorated with slender blendes, separated by a plaster belt frieze. The upper floor was topped with an arcaded frieze and polygonal projections in the corners, supported on stone corbels, above which there was a soaring helmet. These projections received quite an original form, similar only to the one on the west facade of the teutonic palace of the great masters in Malbork.

The Town Hall was an integral part of the entire market square, a huge commercial seat, around which long rows of stalls and wagons were set up on market days, and wells were used on a daily basis. Some parts of the market had their designated purpose, e.g. the wider western part called the “tournament square”, served as a fish market, the northern one was occupied by a coal market, and nearby there was a herb market and a dairy market nearby. Court judgments were also carried out on the market, so a pillory was located in the southeast corner of the town hall.

Current state

At present, the town hall is seat of the main branch of the District Museum. On the ground floor of the eastern wing, collections of Gothic and late Gothic art are collected, mainly from Toruń and from Silesia. In the west wing there are collections of medieval and modern artistic crafts of Toruń, as well as stone fragments of the decoration of the Teutonic Castle. The floor serves primarily as a gallery of modern painting. The second floor is reserved for temporary exhibitions. You can also enter the town hall tower, which is the oldest of the preserved market towers in Central and Eastern Europe. Opening hours and other practical information can be found on the official website of the museum here.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Dybaś B., Toruń, Toruń 2009.

Gąsiorowski E., Ratusz staromiejski w Toruniu, Toruń 2004.

Herrmann C., Mittelalterliche Architektur im Preussenland, Petersberg 2007.

Pawlak R., Polska. Zabytkowe ratusze, Warszawa 2003.