History

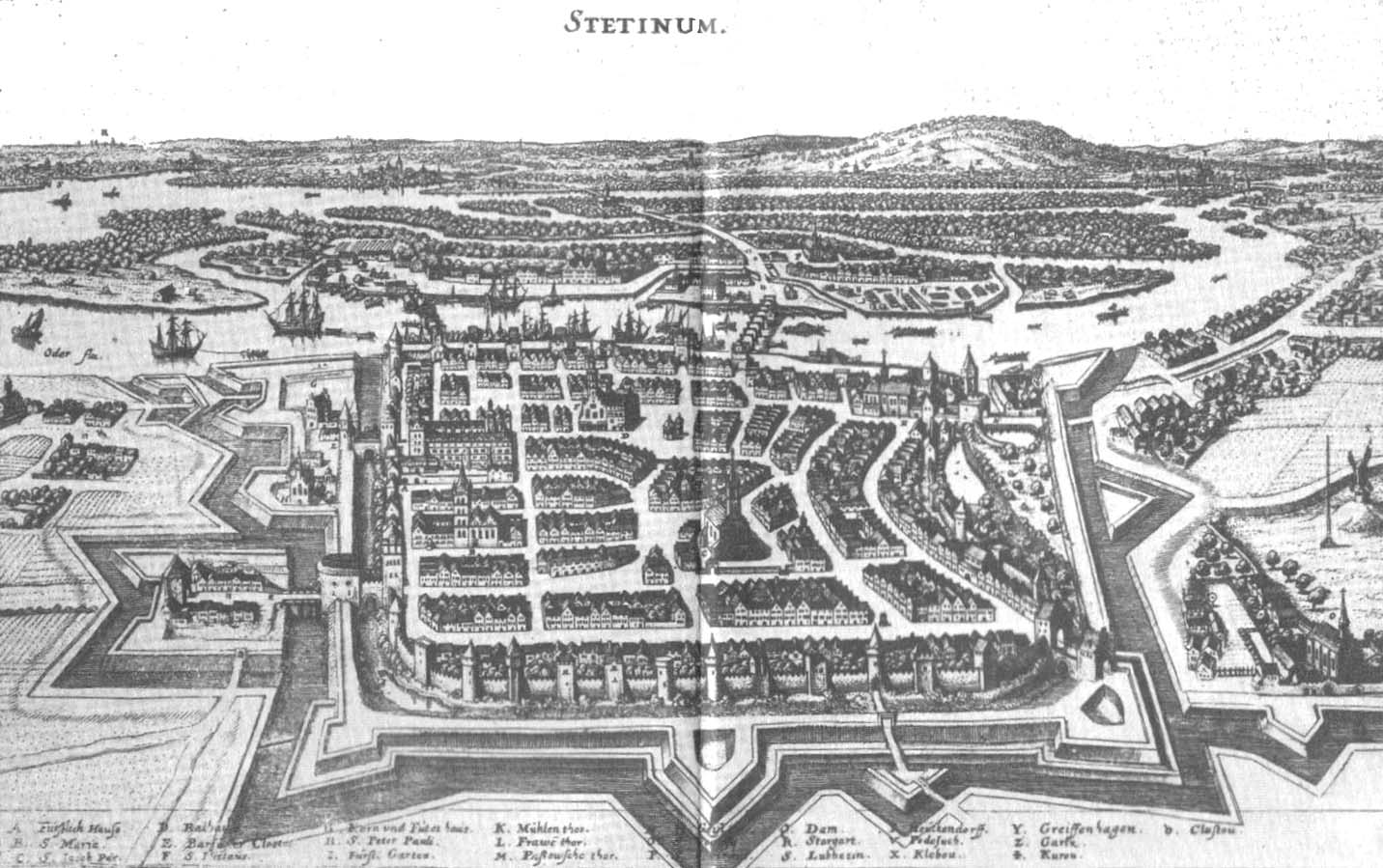

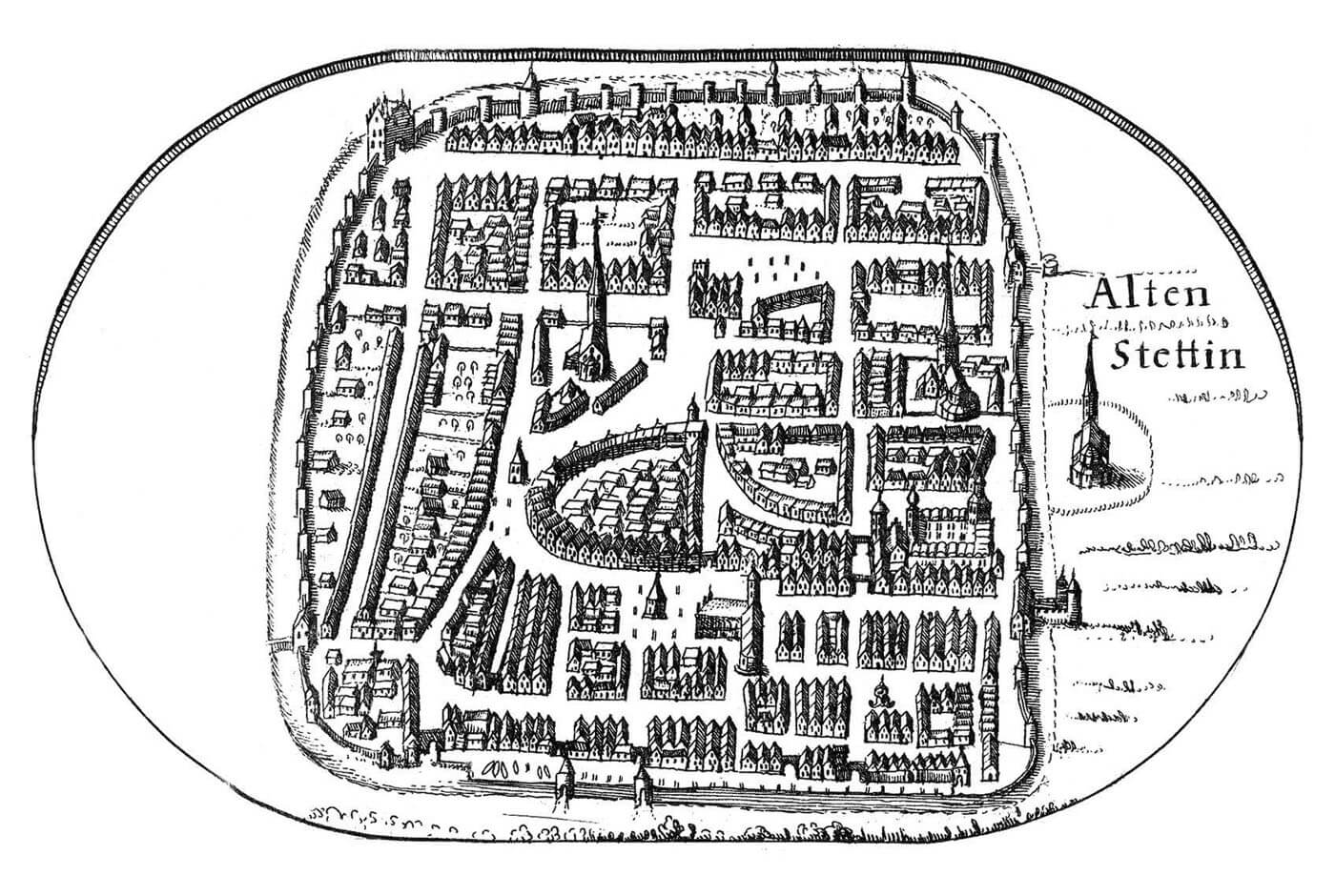

Already in the 7th and 6th centuries BC on the west bank of the Odra there was a hillfort of people from the Lusatian culture, and in the early Middle Ages an important Pomeranian wood and earth stronghold, defending the Oder river ford and being the center of the pagan cult of the Pomorzans. At the end of the tenth century incorporated into the Polish borders, after the death of Boleslaw Chrobry in 1025, it transformed into an independent merchant republic, again subordinated to Poland in 1121 by Bolesław Krzywousty. In 1189, the Szczecin settlement was conquered and burnt by the Danes, but it was quickly rebuilt thanks to the German and Flemish settlers for whom prince Barnim I in 1237-1243 established the town under Magdeburg law, from 1295 raised to the capital of the Pomeranian Duchy.

By the middle of the 13th century, Szczecin had wooden-earth fortifications. The construction of brick fortifications was probably started after the town was founded by Prince Barnim I. The first mention in documents about the defensive walls was recorded in 1283, although already in 1268 the Mill Gate was noted. Their completion must have taken a long time, since in 1318 there was a dispute between the city council and the Franciscan order regarding the financing of the construction of fortifications in the area of the church and friary. At the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, the town was already surrounded by fortifications, the course of which did not change until the end of the Middle Ages. The town walls were then renovated and strengthened many times, e.g. by extending the gates or deepening the moat.

Medieval town walls lost their importance with the advent of early modern bastion fortifications. Erected around Szczecin by the Swedes at the beginning of the 17th century, the new fortifications were still linked to the medieval defense system, which served as the second line of defense of the city. The destruction of almost all of the medieval defensive walls took place only as a consequence of the construction of new fortifications of the Szczecin fortress in the years 1724 – 1740 by Frederick William I. In the second half of the 18th century, their remains were demolished and the existing sections of the moat were filled up.

Architecture

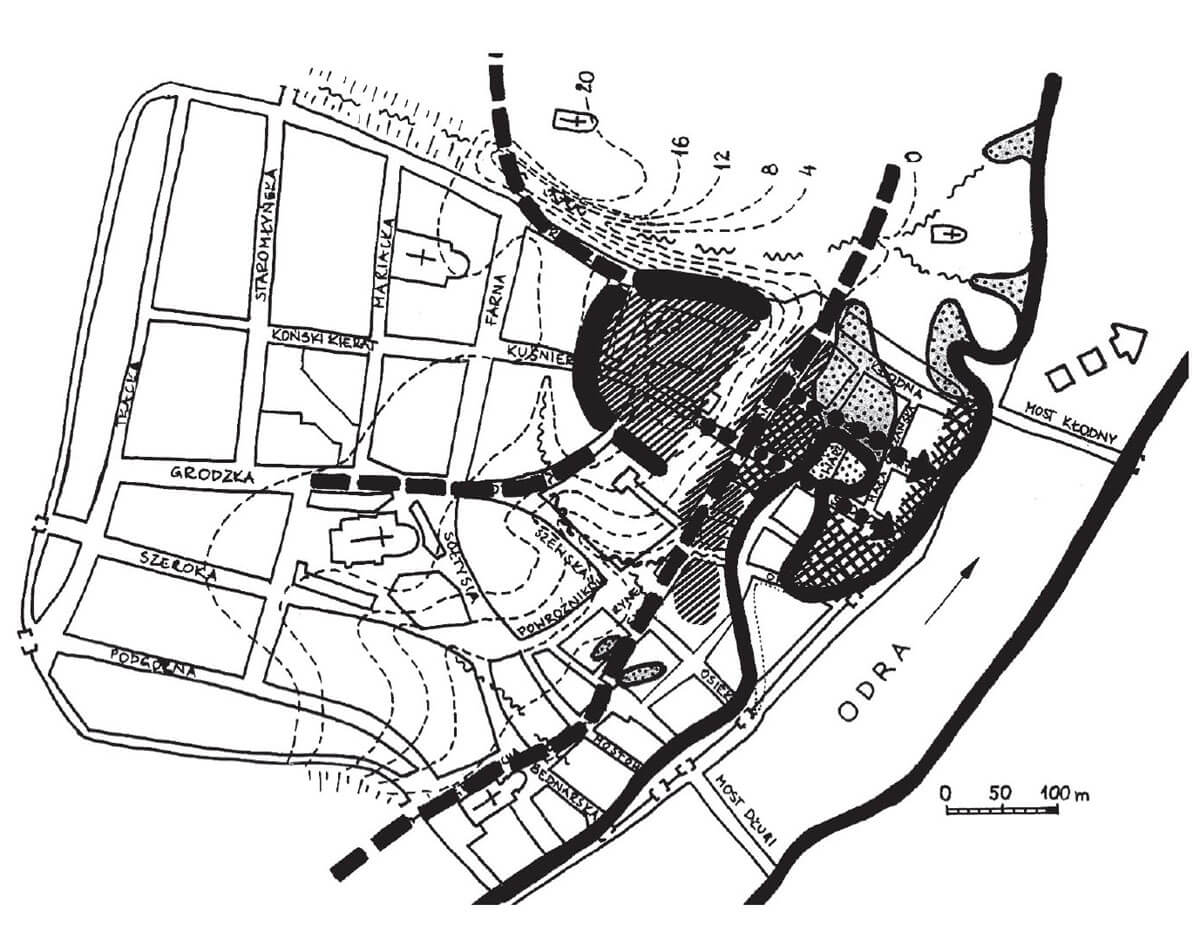

The oldest Slavic settlement from the 8th-9th centuries occupied the area of the later ducal castle, about 1 ha in size, near the river crossing. Its location was decisively influenced by favorable terrain conditions and the possibility of using the earth ramparts of an older settlement of the Lusatian culture. The ditch separated the part located in the highest part of the hill, which probably served sacral functions, and the residential part extending in a semicircle on the eastern side of the hill with dense buildings cut by narrow streets. At the foot of the hill, there was a harbor for crossing to Dąbie and for fishing boats and commercial vessels. It can be assumed that this port was located on the western shore of the relatively shallow Odra bay, which cut into the land and ran approximately parallel to the main riverbed to the area of the later Fish Market. Most likely it was not equipped with quays, but rather boats were pulled up to the gently sloping shore.

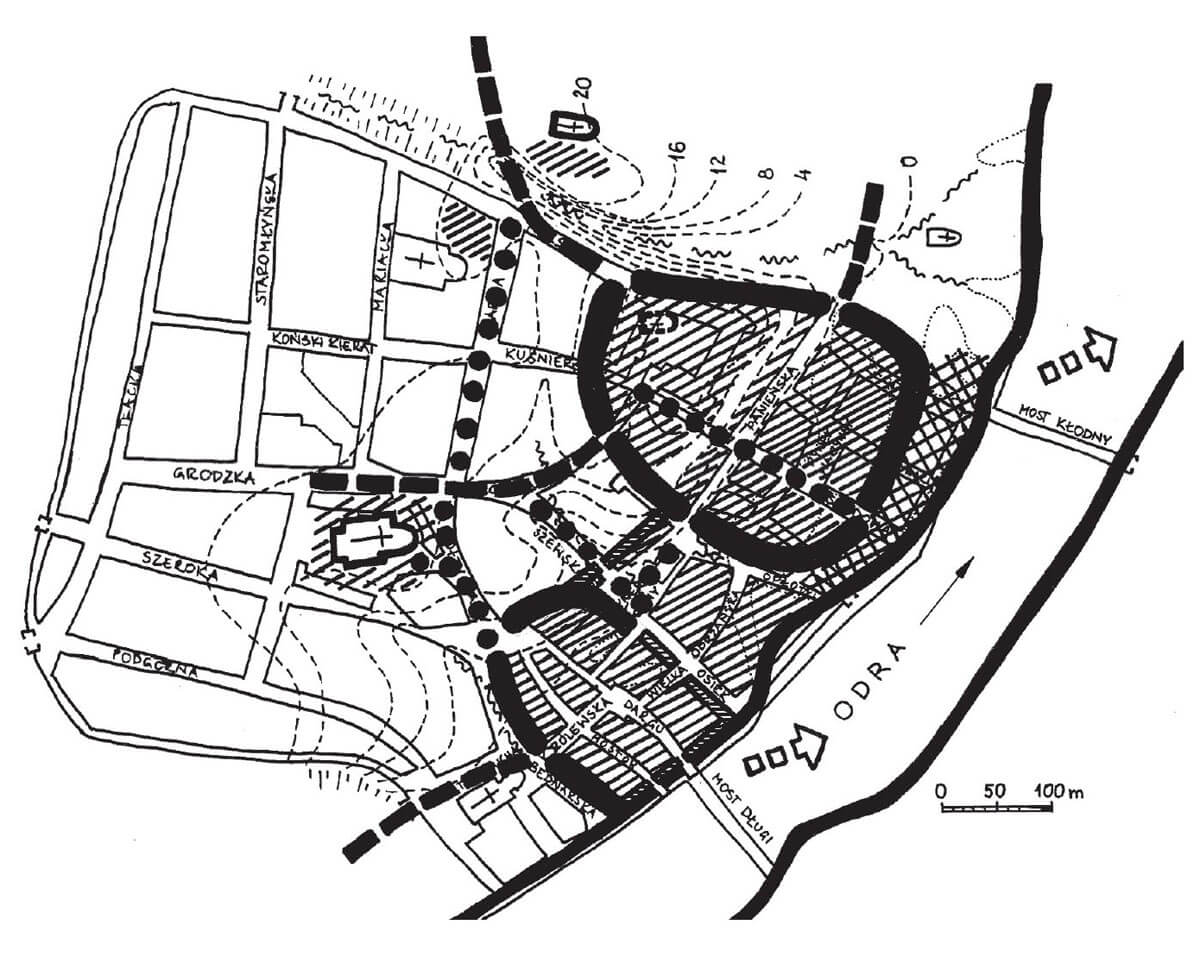

Around the middle of the 9th century, horseshoe ramparts were erected on the Castle Hill, which separated an area of about 1.2 ha. The northern and western embankment of the settlement was additionally surrounded by deep valleys of streams flowing down the slope of the Odra valley, while presumably the stronghold was not fortified from the east. Perhaps the steep natural slope of the Odra valley provided sufficient protection or lighter wooden structures were used there. Along with the earthworks, the buildings were reorganized: the western part retained its sacral character, while the rest of the stronghold focused on craft and merchant activities. Timbered houses, often surrounded by fences, began to appear along the streets covered with wood. Until the mid-11th century, the stronghold was probably accessible through two gates: northern and southern, leading to the main routes running along the Odra River.

In the middle of the 10th century, at the foot of the hillfort, scattered buildings were created, grouped in two parts separated by a stream flowing from the plateau. In the initial phase of development, the spatial layout of this coastal settlement was rather random and unstable. In the 10th century, the plots still occupied relatively small areas and were separated by paths, squares or fences. These areas were also used as a place for boat repairs and craft activities, which were burdensome for the inhabitants of the main hillfort for various reasons. At that time, the spatial layout of the then harbor of Szczecin changed. Probably due to the already significant eutrophication of the bay, in the situation of low water levels it was impossible to enter the original port, so another one, probably located directly on the Oder, had to function.

In the second half of the 10th century or at the beginning of the 11th century, the buildings of the settlement located at the foot of the hill, began to be built from the south and north with earth ramparts connected with the fortifications of the main hillfort. The outer bailey was accessible by gates from the north and south, and the eastern side was not fortified until the end of the 1080s. It can be assumed that by that time the earth fortifications had to enter the waters of the Oder Bay. In the third quarter of the 11th century, in the eastern part of the outer bailey, a ditch faced with wood was made, probably simultaneously serving a defensive, anti-flood and drainage functions. Probably as a result of drainage and at the same time continuous filling of the Odra Bay, in the second half of the 11th century it was completely drained, and thus the harbor by the bay definitely lost its function. The area east of the defensive ditch became the new port of Szczecin. The spatial separation of the port area from the buildings of the outer bailey made it possible to control people moving within its area, which was probably convenient from the point of view of the safety of reloading and boatbuilding works.

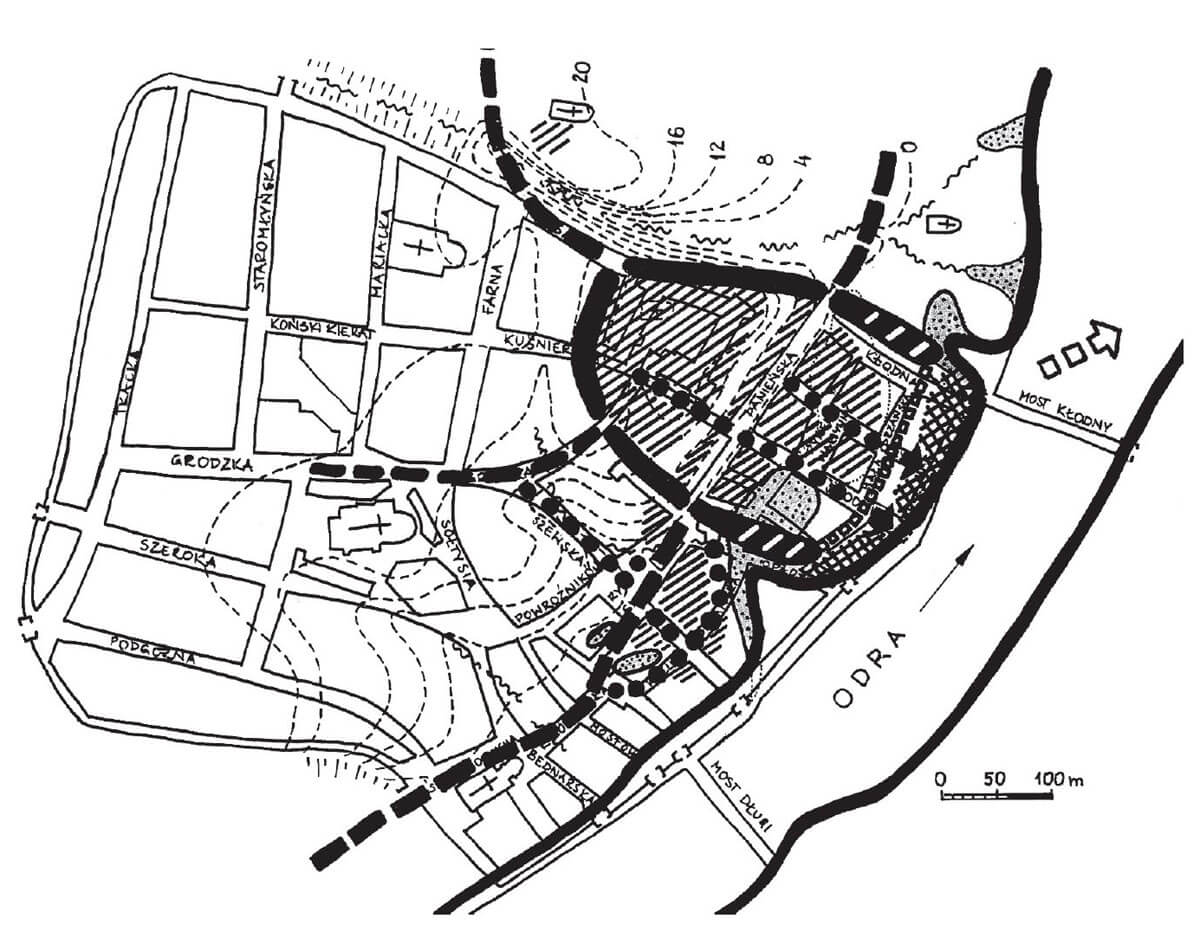

In the 80s of the 11th century, in the place of the former east ditch, a shaft of a hook structure with a clay core was made, closing the outer bailey from the east. After the destruction and rebuilding in the first quarter of the 12th century, it was already a chest structure rampart, it was about 30 meters wide at the base and was shifted in relation to the old embankment to the east, towards the Odra riverbed. Along the inner edge of the rampart there was a passage around the bailey. After the fire in 1138, another rampart was built, also about 30 meters wide at the base. Its outer edge has been moved a few meters east of the previous one. At the expense of the inner part of the rampart, a wide circumferential street was developed, covered with wood. The outer bailey was fortified in this way and occupied an area of approximately 4 ha and consisted of about 400–500 households. As a result of the growing importance of roads leading to the river, at the expense of the roads parallel to the Oder, the previously dominant longitudinal layout of plots was replaced at the end of the 11th century by a latitudinal layout, the main axis of which was a wooden street running towards the Oder. At that time, the outer bailey was the economic center of Szczecin, while the stronghold on the hill was a religious and administrative center. Open settlements also developed around the ramparts and the outer baily, including the settlement at the church of St. Peter and Paul, built to the north-west of the hillfort.

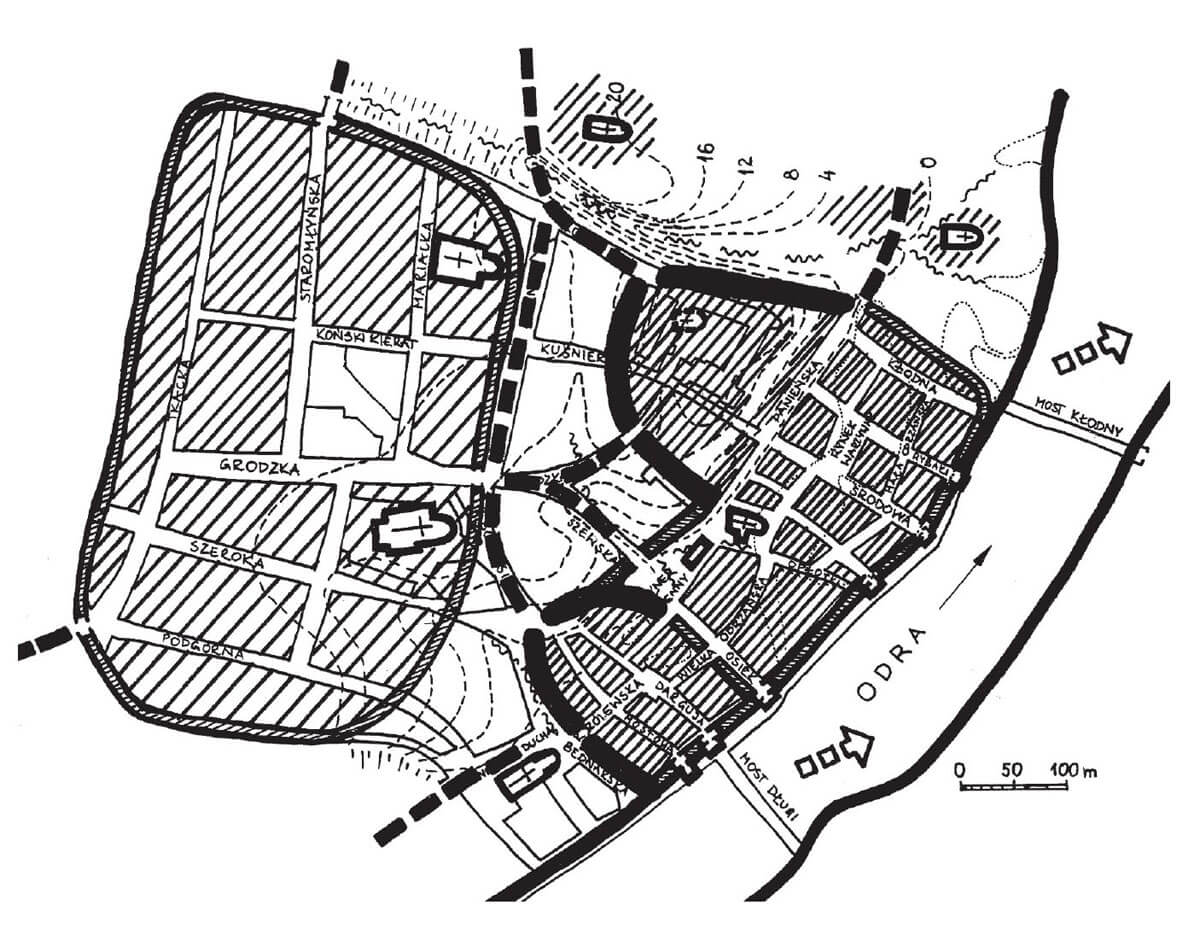

Around the middle of the 12th century, a settlement of German merchants was created in Szczecin, surrounded by fortifications at the end of the 12th century, thanks to which a second outer bailey, next to the Slavic one, was created. It was located south of the Slavic borough, on the Oder, at the Havening port and at the church of St. Nicholas. Perhaps there was also a second, older, German open settlement at the church of St. James. It seems unlikely that there was no fortifications around the inhabited space between the outer baileys. So it can be assumed that some defensive structures connected both settlements: Slavic and German.

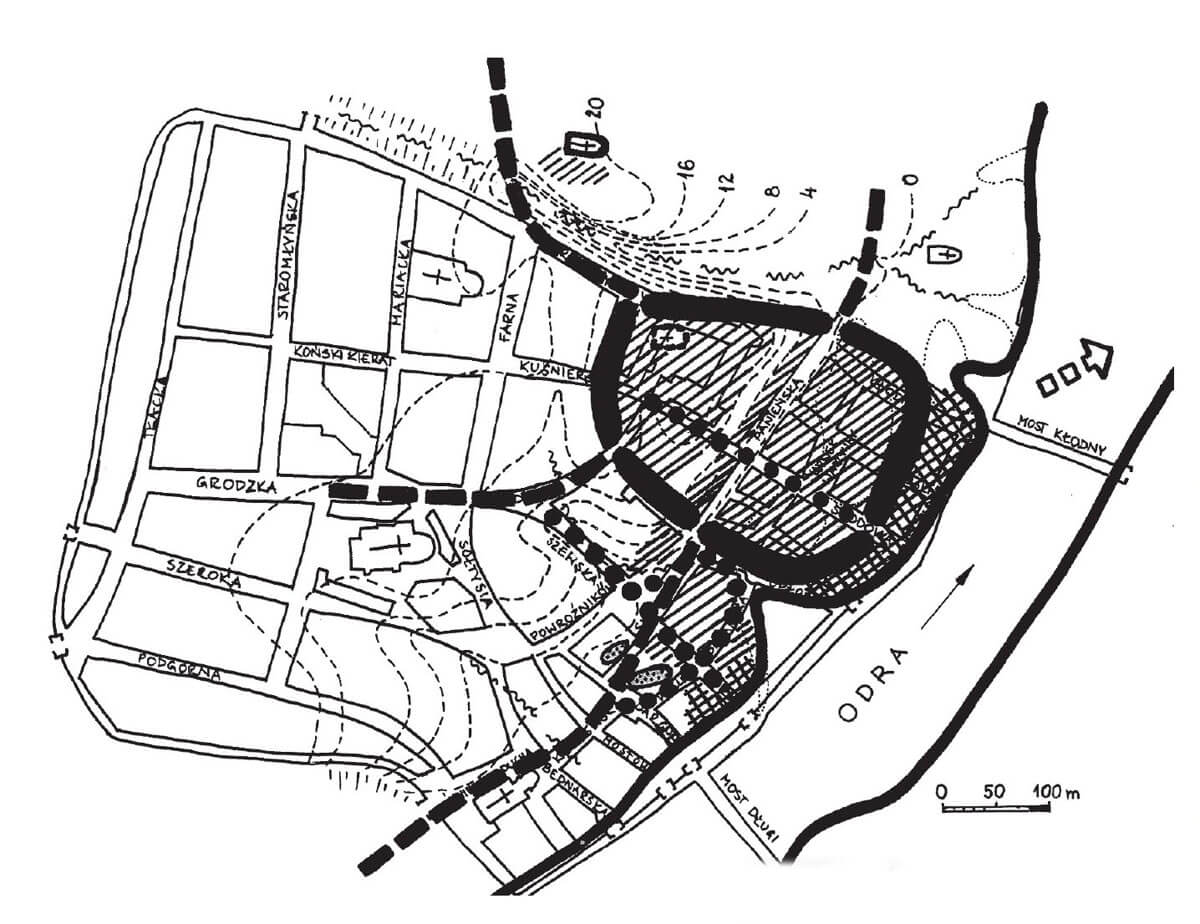

The foundation of the town in the second quarter of the 13th century led to the creation of the “upper town” in previously loosely inhabited areas located on the plateau west of the hillfort and the demarcation of the “lower town” by connecting the German borough with the Slavic borough (as a result of the liquidation of the southern and eastern ramparts of the Slavic outer bailey) . In 1249, Duke Barnim I also included the main hillfort within the town. It can be presumed that due to the lack of space, the inhabitants of the “lower town” modeled on the solutions previously used in the German port, therefore, along the area of the former Slavic borough, wooden piers were erected into the water, analogous to those in Havening port. The most important role in the “lower town” was played by the Sienny Market, next to the town hall, the church of St. Nicholas and streets leading to the port gates.

The connection of the outer baileys was the first stage of preparations for the construction of the town’s defensive walls. Gradually, the “upper town”, “lower town”, the space between them and the marshy surroundings of the Franciscan friary began to be enclosed with brick fortifications. It allowed to unite the adjoining elements of the agglomeration into one coherent structure, which in the 13th century was surrounded by a fairly dense network of villages. Right next to the town walls, along the Oder, there were settlements inhabited by fishermen called Wiks (Upper Wik in the south, Lower Wik stretching from the Cistercian convent in the north to the village of Grabowo). In 1283, a wooden bridge was also built to the opposite bank of the Oder (Long Bridge), and in 1299 the Stone Dike, which made it possible to cross the Odra River to Dąbie, making the crossing by the former Slavic outer bailey to lose its significance. The construction of the Long Bridge made it possible to develop the opposite bank of the Oder. In 1283 the town bought the right-bank area of the later Łasztownia, where vessels were ballasted and ships were built.

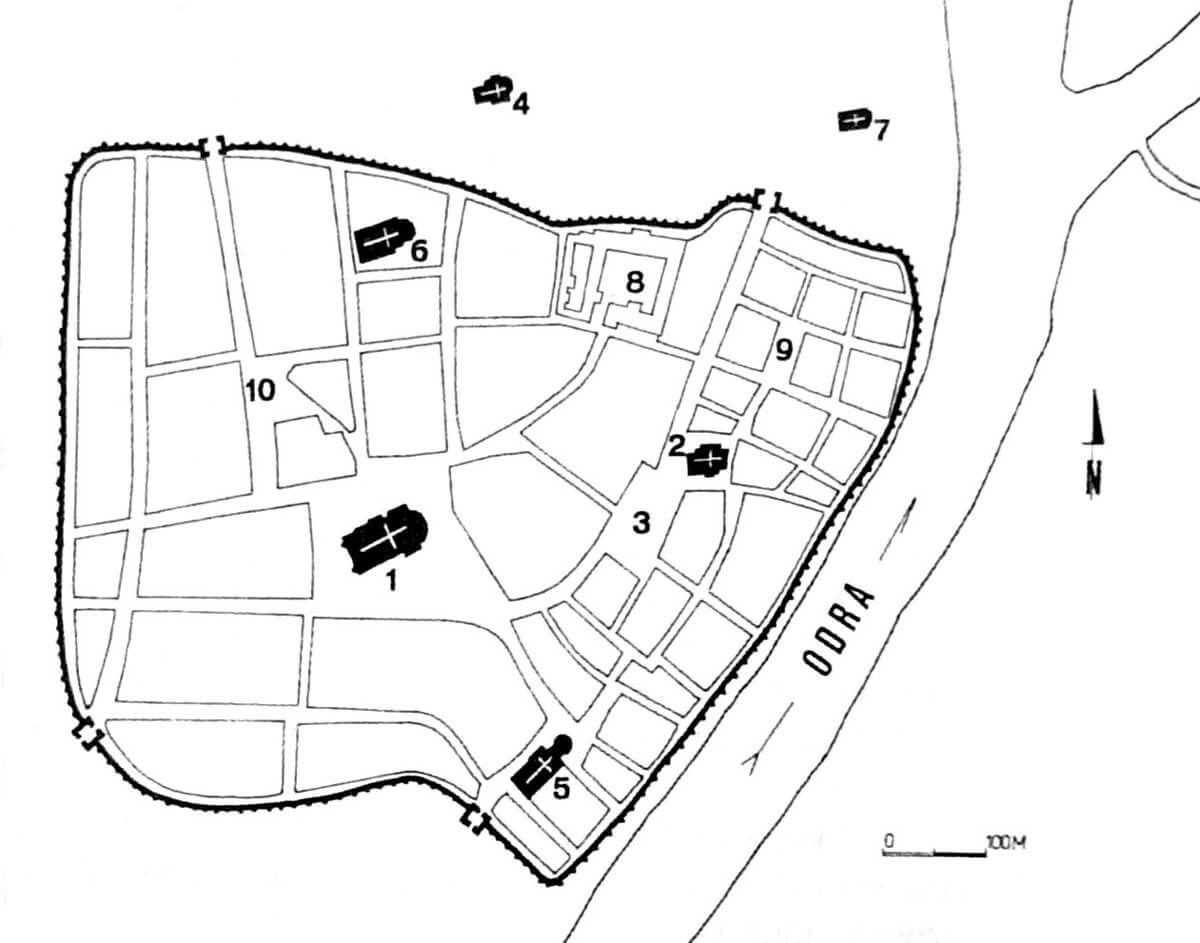

The defensive walls of Szczecin had finally an irregular shape in plan, about 2,500 meters long, slightly elongated on the east-west line, adjacent to the Oder from the east. They were built of bricks on a stone plinth, but the inner core was made of stone rubble bonded with lime mortar. The wall was about 5 to 8-9 meters high. The bricks were laid in a monk bond or Flemish bond. Its thickness at the base was up to 2 meters and it gradually decreased up to 1 meter. The wall was crowned with a battlement, it can be assumed, therefore, that in its crown there was a wall-walk, placed on an offset, perhaps widened with a timber porch due to the small width at the higher levels of the wall. Access to it from the town side was possible thanks to narrow, underwall streets, located parallel to their course.

The fortifications were reinforced with half towers of rectangular or semicircular shape. Initially, they were open from the town side, divided into three floors, the highest of which was an open combat deck. With time, most of the half towers were rebuilt, turning them into full towers. In addition to rectangular half towers, the town walls had cylindrical towers, with diameters from about 6.6 to 9 meters, built in the most sensitive places of the perimeter, for example in the corners of the fortifications. There were about 46 towers in total, of which 9 cylindrical towers and 37 half towers. They were placed quite regularly, every 25-30 meters, and partially extended in front of the adjacent curtains (by about 1.5 meters), so that it was possible to conduct flanking fire and fire an effective crossbow shot.

To the town led four main gates: Mill Gate from north, Virgin Gate from north-east, Holy Ghost Gate from south and Passau Gate from south-west. In addition, there were 7 water wicket gates and two passages located from the wharf. Water gates and wickets, to a lesser extent, had military functions, but above all, they regulated and supervised the communication between the town and the port quay with stores, granaries and piers, where the town’s busy economic and commercial life took place. The water gates did not have such extensive architectural forms as the four main gates, but they took on interesting shapes with rich decorations, especially in the case of the gates of the Long Bridge and St. Mary’s Bridge. The entire ring of fortifications was surrounded by an earth rampart and a moat, and at least from the end of the Middle Ages, the moat was doubled, and an earth embankment ran between them. On the north side, the moat was filled with water, while on the south it could be a dry ditch.

The Mill Gate led to the mills on the Osówka stream. It consisted of a four-sided gatehouse, covered with a gable roof with a ridge perpendicular to the passage, based on Gothic gables. Around the first half of the fourteenth century, it was preceded by a semicircular foregate, connected with the gatehouse by a brick neck. The entrance to the foregate was provided by a drawbridge over the moat. In 1472, an additional polygonal tower was erected in the foreground with a passage in the ground floor, which was surrounded by a timber palisade.

The Virgin Gate was situated near the Cistercian nunnery, on the site of the passage that used to lead to the Slavic suburb. Initially, it had the same form as the Mill Gate, but around the middle of the 15th century, a neck and an external gateway were added, flanked by two cylindrical towers.

The Gate of the Holy Spirit derives its name from the Holy Spirit Hospital, located outside the town walls in the area of Upper Wik. The first gate of the Holy Spirit from the turn of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was located deeper to the north in relation to the second gate, which was established after including the so-called Passau quarter with the Franciscan friary of St. John the Evangelist. At the end of the Middle Ages, the gate complex consisted of a main gate of the gable type and a neck and barbican on a semicircular plan.

The tower of the Passau Gate had a form similar to the other Szczecin gates, so it was of the gable type, but with a ridge parallel to the gate passage. The main gate was connected by a neck placed over the moat with the front gate and with a bridge built over another moat. In front of the gate complex, over time, a tower or gatehouse was erected on a rectangular plan, which had a gable form. It was connected to the palisade, so it was more of a checkpoint in the suburbs than a real defensive work. In the vicinity of the gate, outside the town walls, there was a hospital complex dedicated to St. George.

Current state

From the old medieval fortifications to our time, only Virgin Tower, also known as the Tower of the Seven Coats, is preserved, as well as a fragment of the wall at Podgórna Street, once adjacent to the gate of the Holy Spirit. Moreover, at Św. Ducha 5 Street, the relics of the cylindrical tower and fragments of the defensive wall were discovered, which, after archaeological research, were incorporated into modern buildings, and their course was marked at ground level. The walls of the Virgin Tower at the level two upper floors are a reconstruction, as it was partially dismantled at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, and then transformed into a burgher’s house. Its original silhouette was revealed only after the destruction of World War II. Historians link the name of the Seven Coats Tower to the guild of tailors, who laid down for the maintenance of the building.

bibliography:

Kozłowska I., Fortyfikacje Szczecina, [b.r.] Szczecin.

Krośnicka K., Rekonstrukcja ewolucji układu przestrzennego średniowiecznego miasta i portu Szczecin, “Architectus”, nr 4 (48), 2016.

Pilch J., Kowalski S., Leksykon zabytków Pomorza Zachodniego i ziemi lubuskiej, Warszawa 2012.

Rębkowski M., Pierwsze lokacje miast w księstwie zachodniopomorskim. Przemiany przestrzenne i kulturowe, Kołobrzeg 2001.