History

The construction of the church began in the first half of the fourteenth century, after a fire of the town from 1313, from which the previous church standing in this place survived. It had to be built of stone, because as a wooden it would have no chance of surviving the disaster. The decision to build a new, larger church had to be influenced by the rapid development of the settlement, transferred in the mid-thirteenth century to German law. Preparations for this great undertaking were probably undertaken much earlier, as evidenced by the pope’s issuing of indulgence letters as early as 1288-1303 and the scribe Henry donating in 1323 a half mark of rent for the construction of the parish church. A few years later, during the reign of Bolko II in 1327, an indulgence was granted to all those who contributed to the construction, decoration and lighting of the temple. Tradition ascribed the foundation stone to Bolko II of Świdnica in 1330.

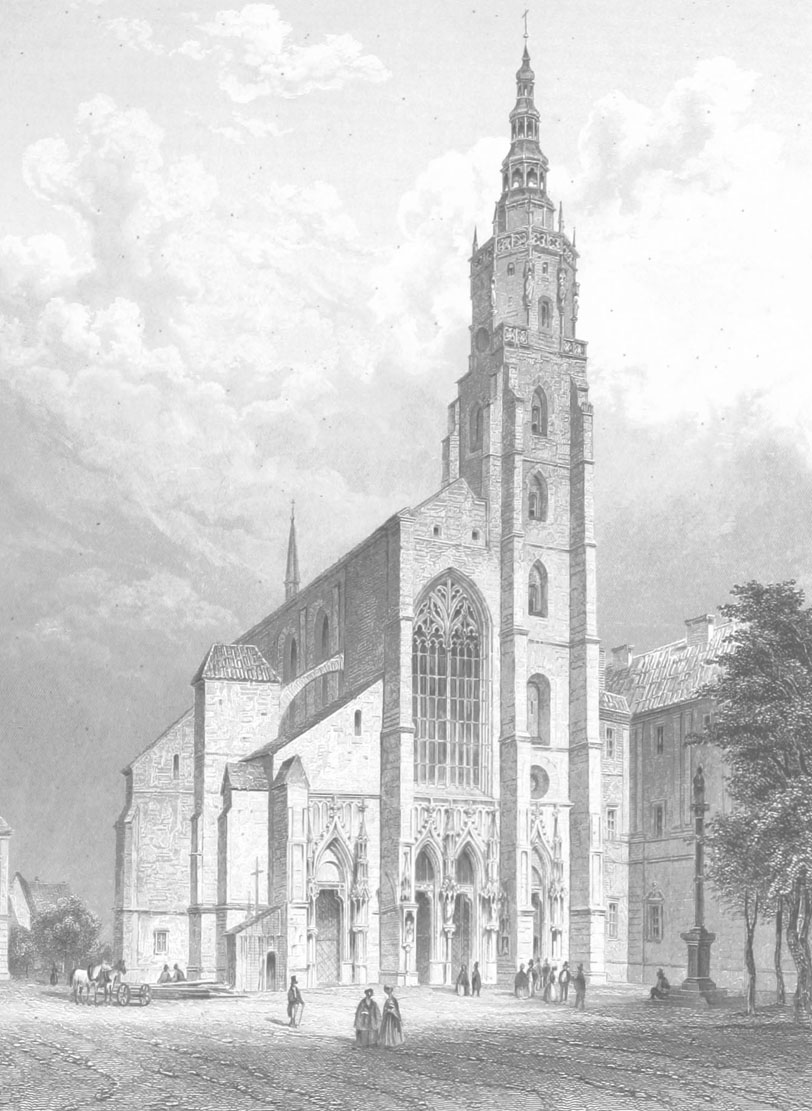

In 1353, the construction of the chancel was completed, and in 1385 a settlement was carried out between the city representative, Nicholas Lewe and master Apecz, the bricklayer. The construction works were probably managed by the stonemason, master James, who also supervised the construction of the parish church in Strzegom. Works stretched throughout the fifteenth century (in 1405 donations were recorded for the construction of the tower, in 1410 for repairs at the aisle, in the years 1456-1468 indulgences were granted to obtain funds for expansion, in 1486 the foundation of the roofs was recorded), until it was only in 1525 that the construction of one of the two planned towers was completed. Its builder was the stonemason Petr Czekyn (Zehin), one of the most talented masters from Saxony. The second, north tower was never completed.

In 1532, one of the city councilors entered the southern tower, where weapons were stored, accidentally caused a fire from which the roofs burned down and the vaults collapsed, and then the western gable also collapsed. The work on re-vaulting the church was entrusted to Lukas Schleierweber, who reportedly completed this task together with seven workers within a very short period of 14 weeks. Soon, in 1546, a huge window was placed in the renovated western wall, the roofs covered by the shingles were replaced with tiles and the tower was renovated.

In the years 1561-1629 the church was used by Protestants. In 1662, the patronage of the temple after a long dispute with the Poor Clares from Trzebnica was taken by the Jesuits, who baroqueized the interior at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries. After the secularization of the Jesuit order, the church was converted into a grain warehouse in 1757-1772 with the consent of the Prussian authorities. This resulted in the need for a thorough renovation carried out in the years 1893-1895. Unfortunately, because of it, the church lost many original architectural elements. Western portals were converted, the interior was painted with oil paints and the stonework of the stairs leading to the upper St. Mary’s Chapel was destroyed.

Architecture

The church was lit by pointed windows inserted between the buttresses, of which a large ogival window filled with tracery from the mid-16th century, located on the west facade deserves special attention. It received impressive dimensions: 18 meters high and 9 meters wide. Five very tall and narrow windows of the east closing of the central nave were also distinguished, pierced by almost the entire height and emphasizing the slender proportions of the nave. The light into the aisles came only through the windows of the chapels, most of which were opened to the interior of the church with all its width. The external façades of the church were placed on a plinth with a moulded cornice, and were also framed with a crowning cornice with gargoyles. The tower was divided into storeys by cordon cornices.

The entrance to the church was placed on four western portals from around 1421 (date carved on the figure of St. Wenceslas in the northern corner). They all received pointed closure of moulded jambs and (except the southern portal) gables with crockets. Carved symbols of Evangelists were mounted on the door supports, and the crucifixion scene in the tympanum of the tower’s portal. Each of the portals was flanked by bundles of slender columns with leafy capitals, which became the support for the carved figures of church patrons. They were covered with stately canopies bristling with pinnacles and crockets. The portal placed in the north wall of the church was shaped differently. It received a pointed and moulded form in the upper part, filled with a trefoil tracery, which was supported on figural, very small consoles. Interestingly, their themes were satirical, probably they were about Aristotle and Filis as well as Samson and Dalila. Figural performances (of greater than natural height) were also placed on the last floor of the tower, which goes into an octagon. There were columns at the corners, on which statues of saints were placed, carved in stone only from the front and sides. Their backs were peeled to reduce weight.

An interesting twelve-sided crypt resembling a chapel was placed under the chancel during the works from the end of the 14th or early 15th century. It caused the elevation of the chancel and the main altar above the level of the church and their excellent visibility from the farthest places of the interior. Crypt’s stellar vault was supported by a round pillar in which all ribs gathered concentrically. The other ends of the ribs were mounted on wall consoles in the shape of sandstone masks (only six survived). The 12-sided part of the crypt was connected to the octagonal room, which served as the vestibule accessible from the outside. Vestibule ribs converged concentrically to the central boss, and at the other ends flowed down and blended into the walls. As the crypt was partially hollowed out into the ground, the light reached it only through pointed windows, in the vestibule two-light and with traceries, in the proper crypt a bit simplified, embedded in deep niches.

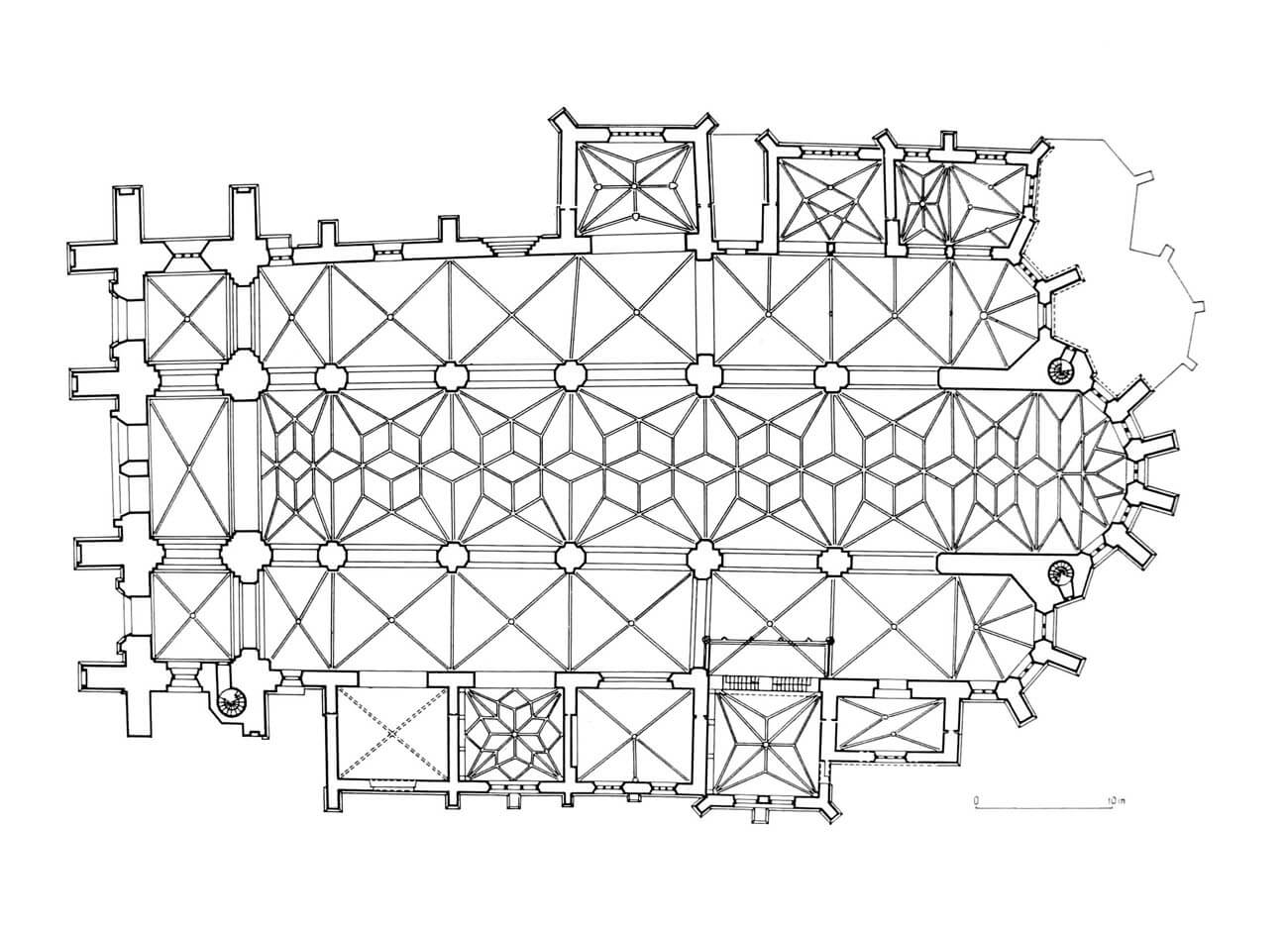

The central nave after the fire in 1535 was crowned with a net vault, set lower than the original vaults. It was opened to the aisles with pointed, moulded arcades, set on rectangular pillars with moulded corners and low plinths with moulded bases. From the side of the aisles pilaster strips were applied to the pillars. The north and south aisles were covered with cross vaults with ribs fastened with circular bosses and mounted on pyramidal and figural corbels. These corbels were decorated with small-figure sculptures, among which were Adam and Eve, St. George killing the dragon, lion tamer, Jonah and the whale, banishment from paradise and coats of arms of local families. Between the second and third bays from the east, semi-octagonal arch bands were used. The vaults of the northern annexes received cross, three-support and stellar forms.

Current state

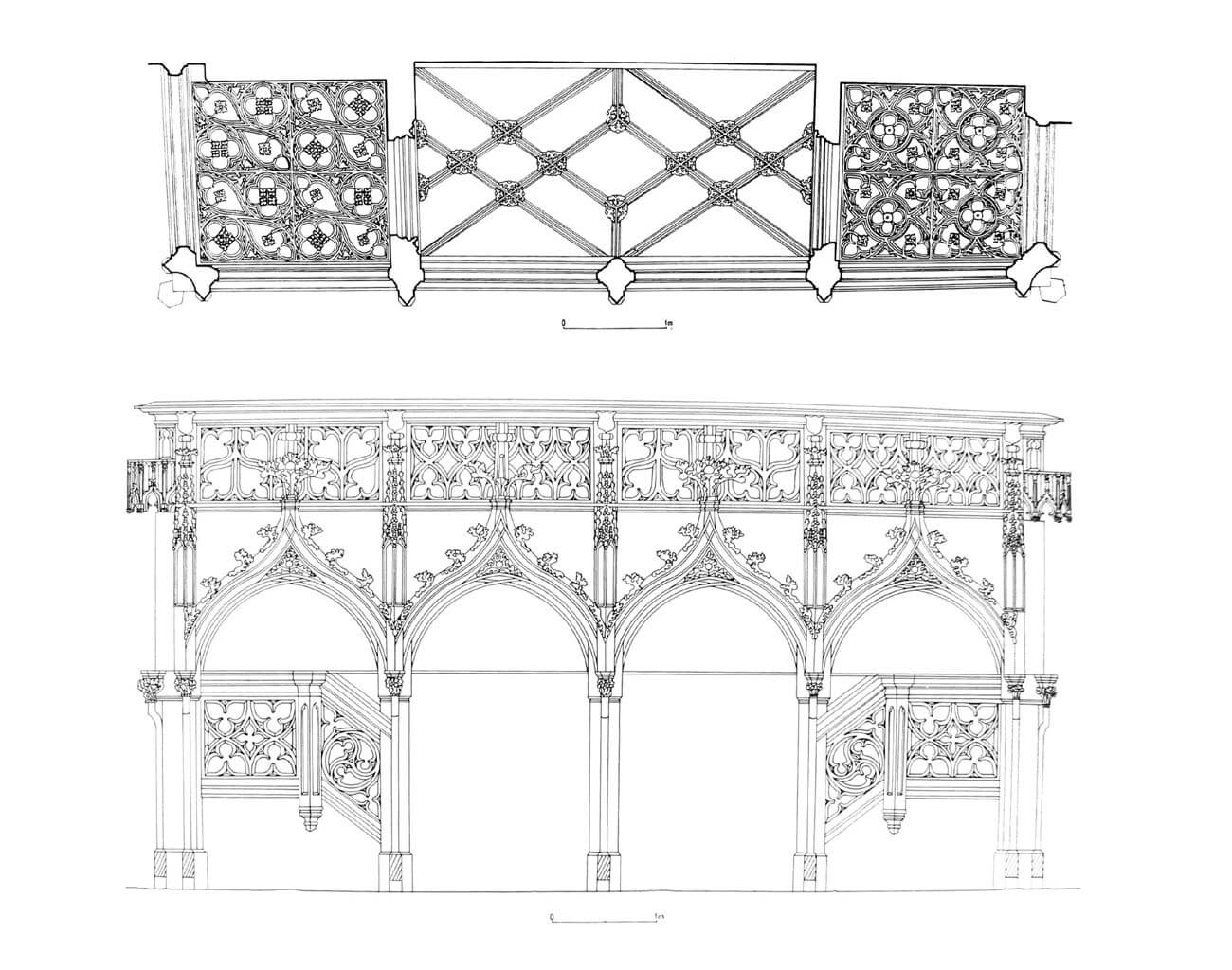

Despite the Baroque transformation of the interior and the unsuccessful renovation of the late nineteenth century, the church is today a great example of Gothic architecture, a combination of monumental momentum and architectural splendor. Among the survived elements of its medieval furnishings, the most valuable is a Gothic polyptych from 1492 made by students of Wit Stwosz. In addition, you can see the sacramentary and timber pietà from the late fifteenth century. In the parish garden, on the other hand, there are late-Gothic gargoyles removed during the renovation of the nineteenth century, and the original Gothic balustrade of the organ choir, which was replaced in the sixteenth century.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Hanulanka D., Świdnica, Warszawa 1961.

Pilch J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska, Warszawa 2005.

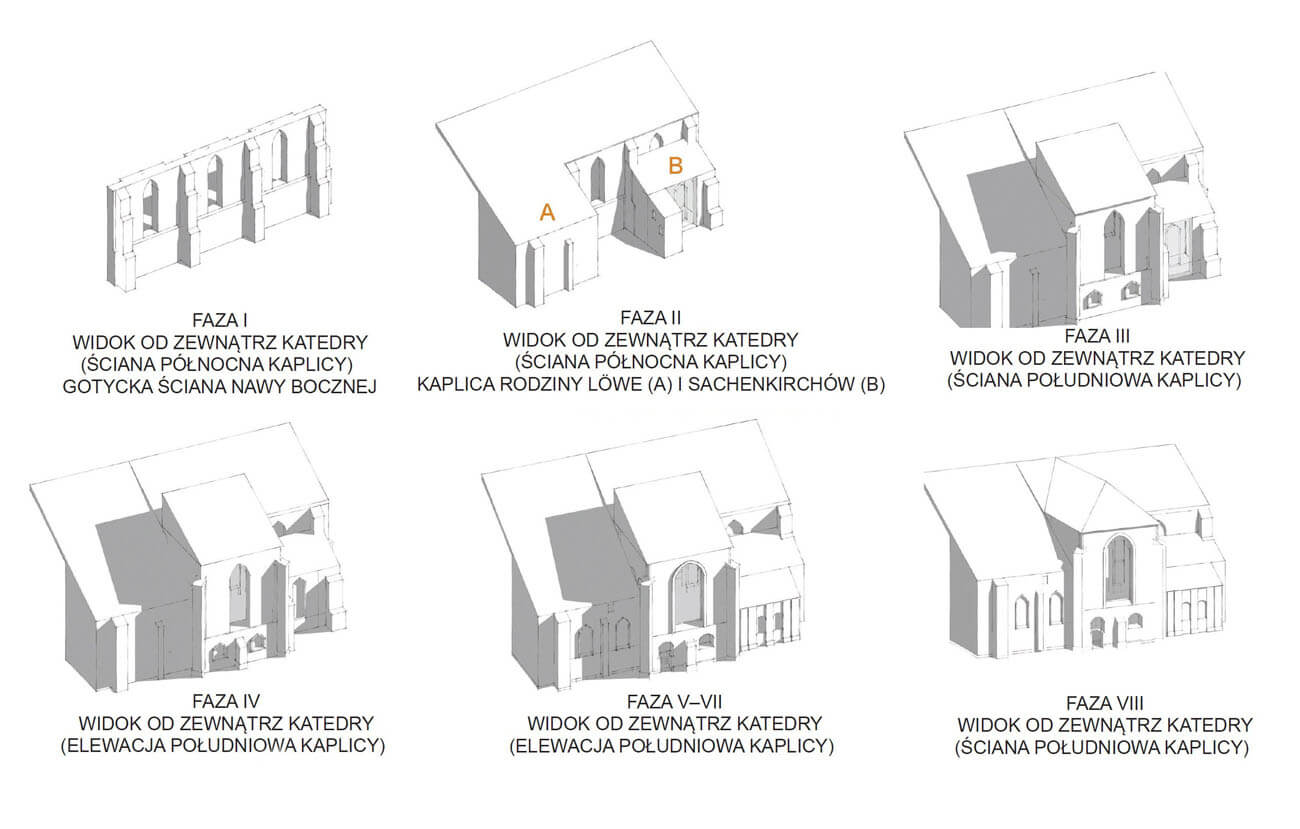

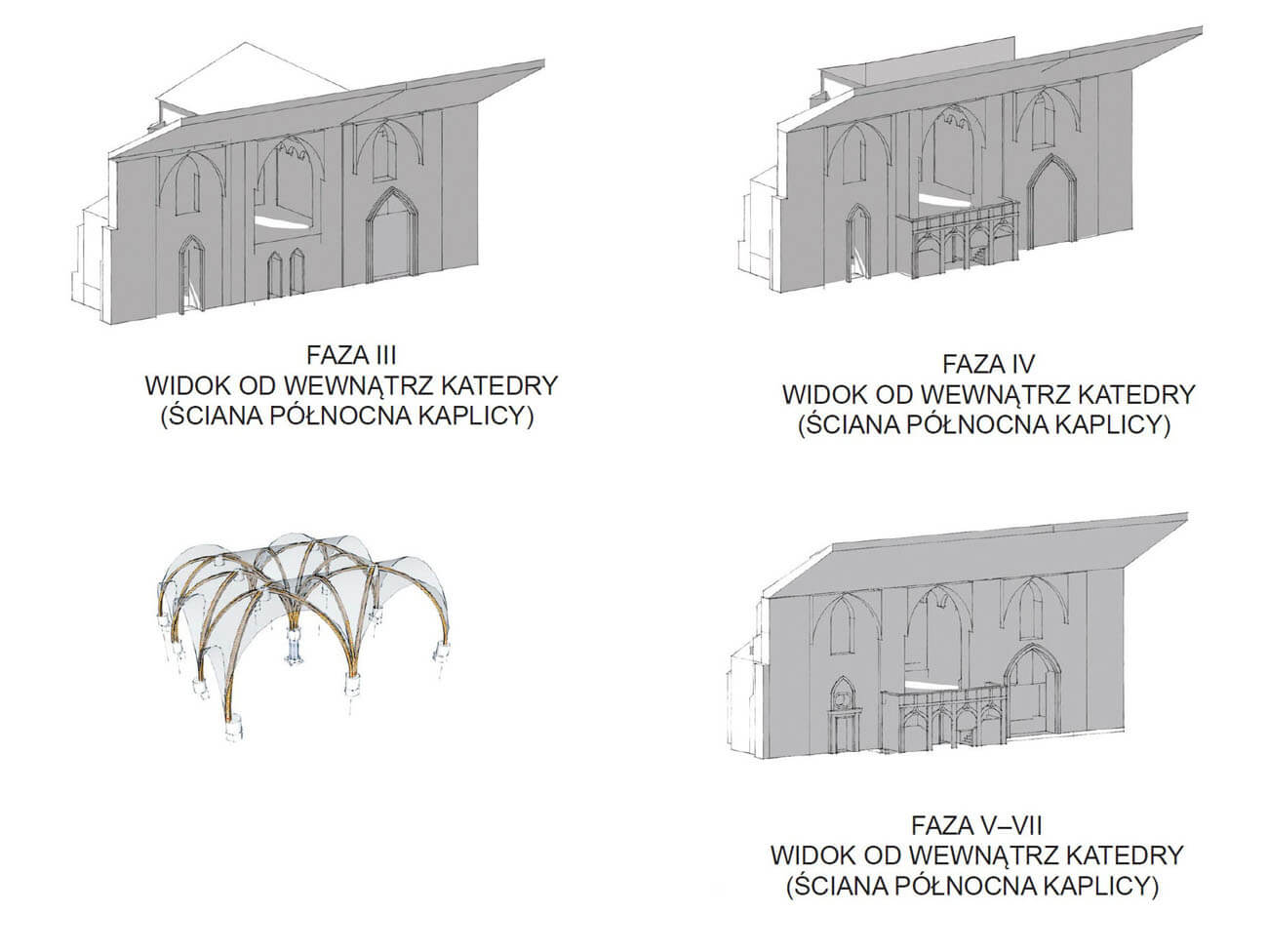

Smirnowa L., Wojciechowska G., Zgraja A., Badania architektoniczne kaplicy Mariackiej w świdnickiej katedrze [w:] Dziedzictwo architektoniczne. Badania oraz adaptacje budowli sakralnych i obronnych, red. E.Łużyniecka, Wrocław 2019.