History

The church of Corpus Christi was built in the place of the former settlement of Błonie, where according to legend, at the end of the fourteenth century hostes stolen and desecrated by Jews were found. Shortly after these events, a wooden chapel was established in the place where the host was found, and the growing fame of this place meant that in 1406 kong Władysław Jagiełło founded a Gothic church and a Carmelite monastery. The church was personally important for Władysław Jagiełło, who vowed before the Grunwald campaign that he would make a pilgrimage to it, which he realized after the battle, when he sent the war spoils to the Poznań church (Gothic monstrance) and in 1419, when he went to it from Pobiedziska. The king also visited the Corpus Christi church after other victorious war campaigns, and according to the chronicler Jan Długosz, also before expeditions.

The square for the construction of the church was donated in 1406, at which time a commission was formed consisting of representatives of the Poznań bishop, the staroste of Wielkopolska and city councilors, who were to supervise the construction works. In the years 1424-1425 a transport of bricks and stones was recorded from Starołęka, a village on the Warta river belonging to the monastery, and in 1433 it was reported about the transfer of funds by Jan Pakuła for stained glass. By the beginning of the 1430s, most of the chancel was erected, perhaps together with its vault and the monastery buildings (in 1426 there was a record of Catherine, the wife of Nicholas, a brazier from Piaski “pro fabrica Conventuali loci Corporis Christi”).

The church and monastery gained their full Gothic form in the years around 1465-1480. The long break that took place between the completion of the chancel of the church and the beginning of the construction of the nave probably resulted from the unstable political situation after the death of King Jagiełło, when the monastery could not count on the support of the new ruler, Władysław III, who was mainly involved in Hungarian affairs. In 1465, King Kazimierz Jagiellończyk donated the area for a brickyard, while until 1478 the Carmelite convent was in dispute with Wojciech Łobżański for payment of 150 fines for the completing of the last parts of the church. The work could be delayed because of the wetland, for it is known that in 1472 the papal bull granted an indulgence for some reconstruction, and thus removal of unknown damages, possibly related to floods. The effort of the state related to the Thirteen Years’ War conducted until 1466, could also have been a hindrance.

In 1657 the monastery was burned by the Brandenburgers. Destruction was removed only in 1664, when the vault of the nave was rebuilt, Baroque façade was added and plastered. At the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the extension of the southern aisle, a stubby tower was erected, and in 1726 the Chapel of Our Lady of the Scapular was erected on the north side of the chancel. In 1826 the Prussian government dissoluted the monastery, and the abandoned site began to decline. The church was repaired by the Reformers in 1856. The new owners carried out a thorough renovation. At the same time the monastery buildings were taken by the Prussian army, changed into barracks, and then into prison. In 1899 thanks to archbishop Florian Stablewski, church became a parish for Wilda, Rybak and Piaski. During World War II the Germans changed the church to a warehouse destroying many of the monuments. During the fighting in 1945, part of the vault and two of the five chancel windows with tracery were destroyed. Renovation was carried out in 1946-1947.

Architecture

Originally, the church was far away from the buildings of the Poznań suburbs, south of the Wrocław Gate. It was separated from them by one of the branches of the Warta River, called Struga Karmelicka. It was located in wetlands and marshy areas, which also required a lot of work and dragged the construction process.

The church was built of bricks laid in a Flemish bond, with the use of head-laid, fired to black colour zendrówka. What’s more, originally in the Middle Ages, the nave of the church was faced with glazed yellow-green bricks, which certainly reflected the sun’s rays, creating the effect of a shiny surface. This created a clear contrast with the glaze-free chancel and the stone decoration of the windows.

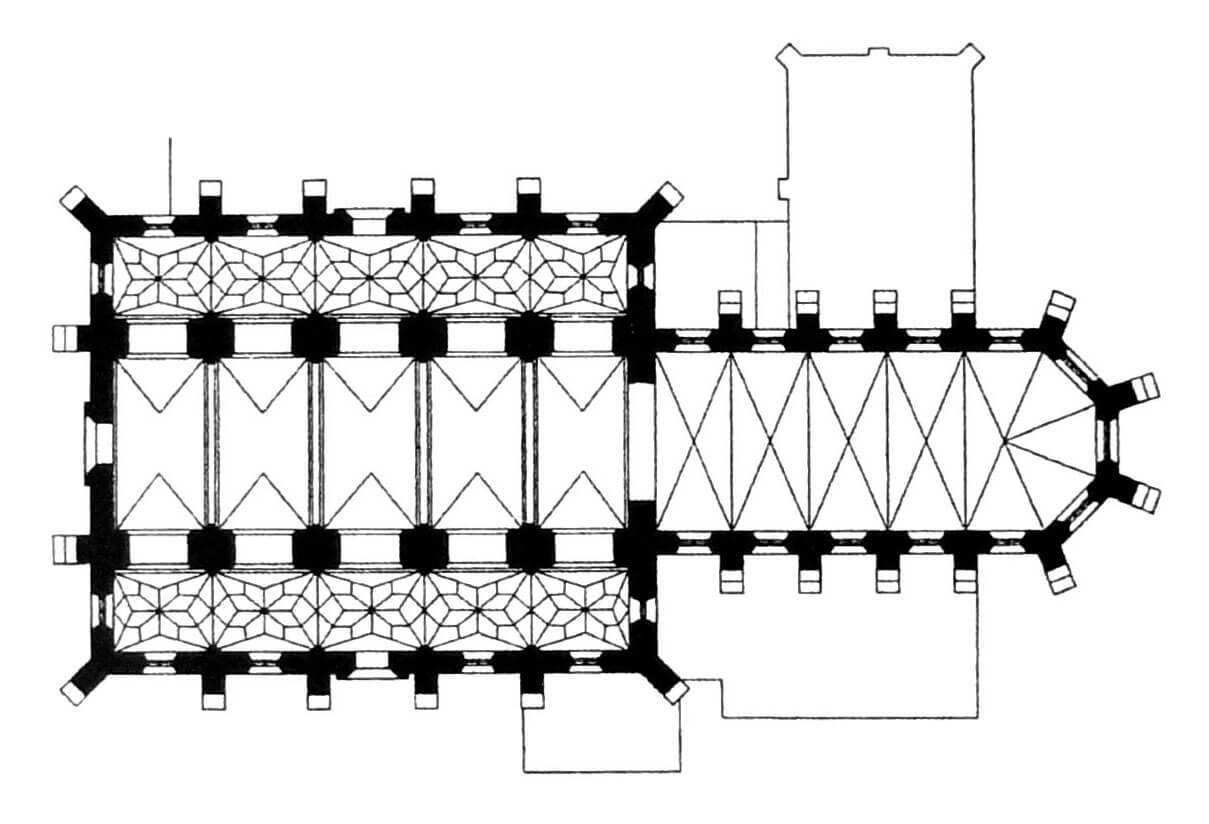

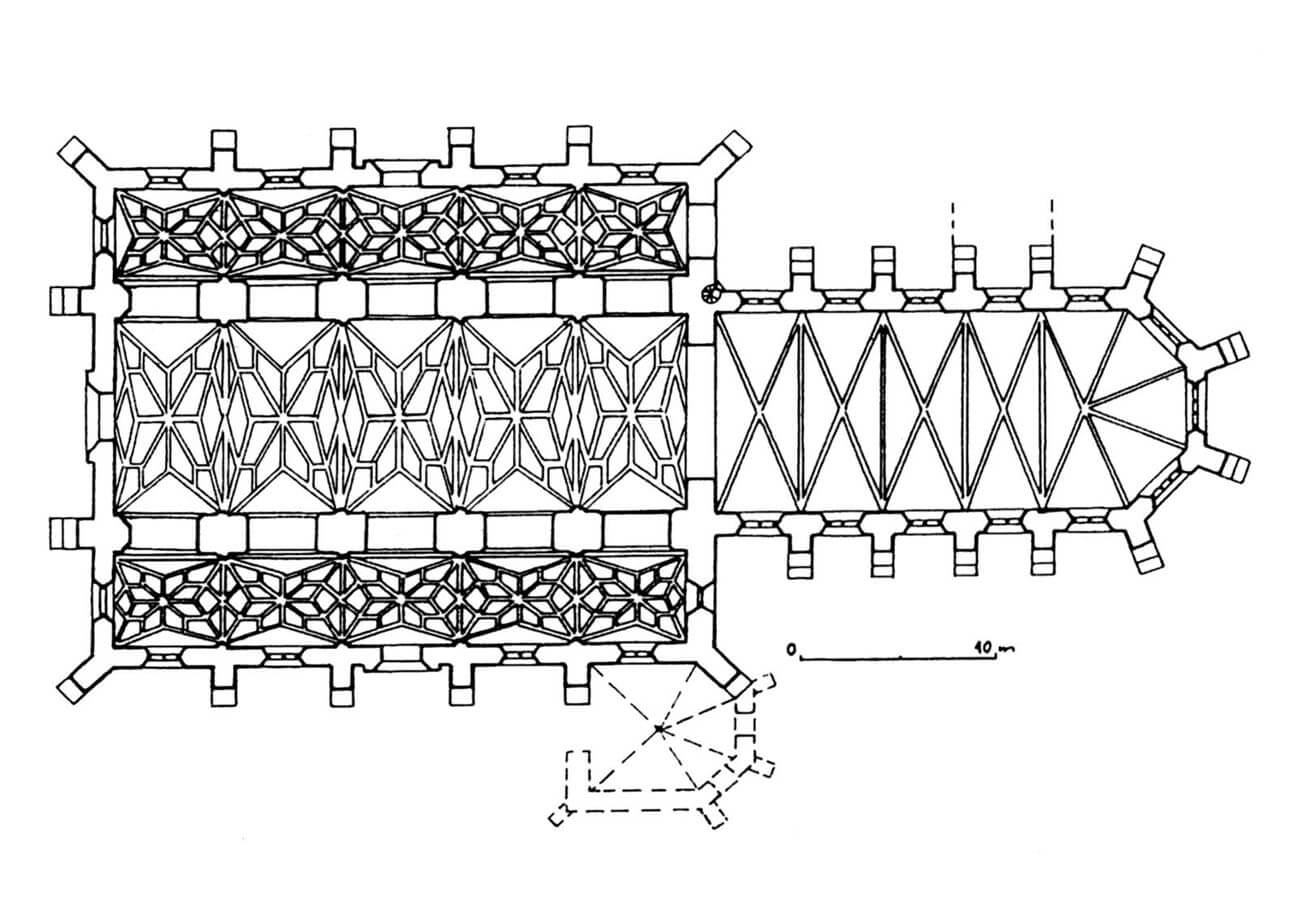

The church was built as a pseudobasilica with five-bay central nave and two aisles, in which the aisles were separated by ogival arcades, supported on moulded pillars. An elongated, four-bay, polygonal ended chancel with the same height as the nave was attached to the nave, which was an unusual solution in the Gothic architecture of Greater Poland (Wielkopolska). A small chapel in the form of a aisleless annex with a three-sided closure adjoined the eastern bay of the southern aisle. The whole was a lofty structure, but compact, slender by the high buttresses surrounding it, once crowned with pinnacles.

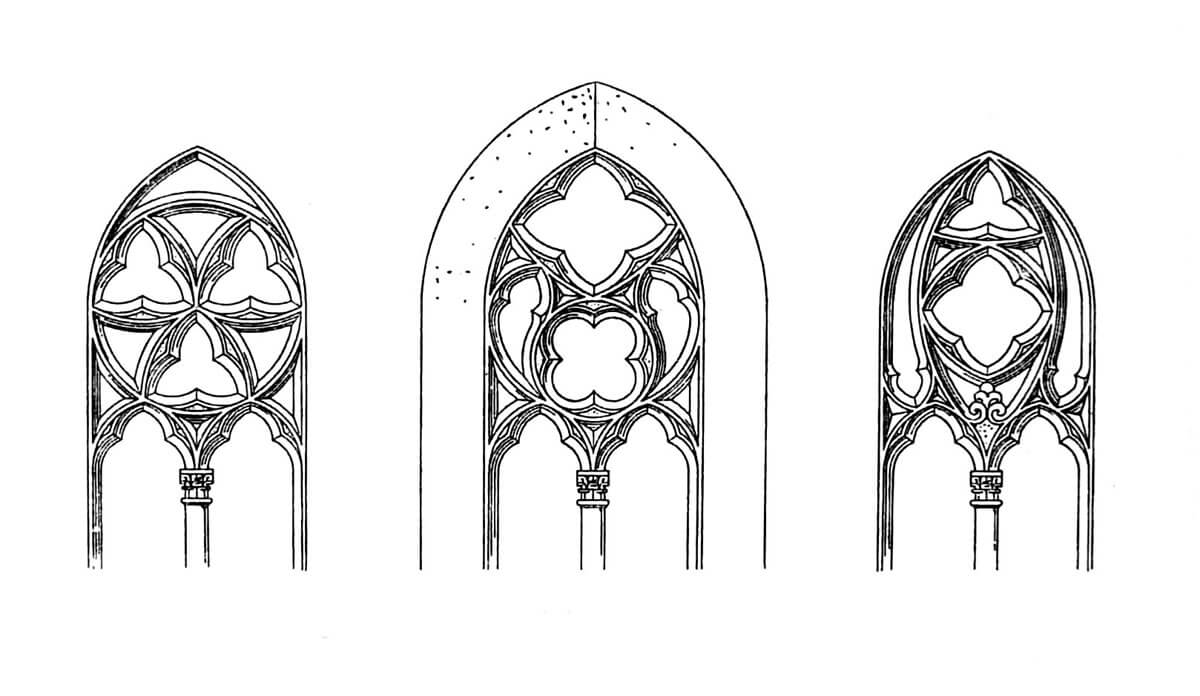

Three portals made of glazed, colored bricks led to the church. The most important from the west leading to the central nave and one from the north and south to the aisles. The interior of the church was illuminated by high Gothic ogival windows filled with stone tracery in the chancel and simpler shafts in the nave. The dark central nave was illuminated only through thick pointed arcades and windows of the aisles, characterized by high height. It contrasted with a much brighter chancel with large windows.

The chancel was covered with a Gothic cross-rib vault, while stellar vaults were founded in the aisles and in the central nave. Powerful, very massive inter-nave pillars were founded on a square plan and fitted with brick moulding in the corners. Placing such large pillars with their dense spacing dictated by the bay divisions previously defined in the longitudinal walls, made the aisles of the church largely independent interiors, connected by narrow arcades, extremely deep, and at the same time relatively low (compared to the height of the central nave). The builders probably sought to reduce the span of the arcades between the aisles, and thus increase their number, due to the unfavorable foundation of the church on wet ground.

Inter-nave pillars separated rectangular bays in the central nave, positioned transversely in relation to the church axis, and twice narrower, close to squares bays in the aisles. The chancel uses bays as wide as in the nave, but slightly shallower. The interior façades of the chancel were devoid of articulation, except for the elongated window openings set in splayed recesses closed with pointed arches. Both main parts of the church were separated by a soaring arcade of the chancel arch and originally a rood screen, whose height probably reached the moulded part of the arcade.

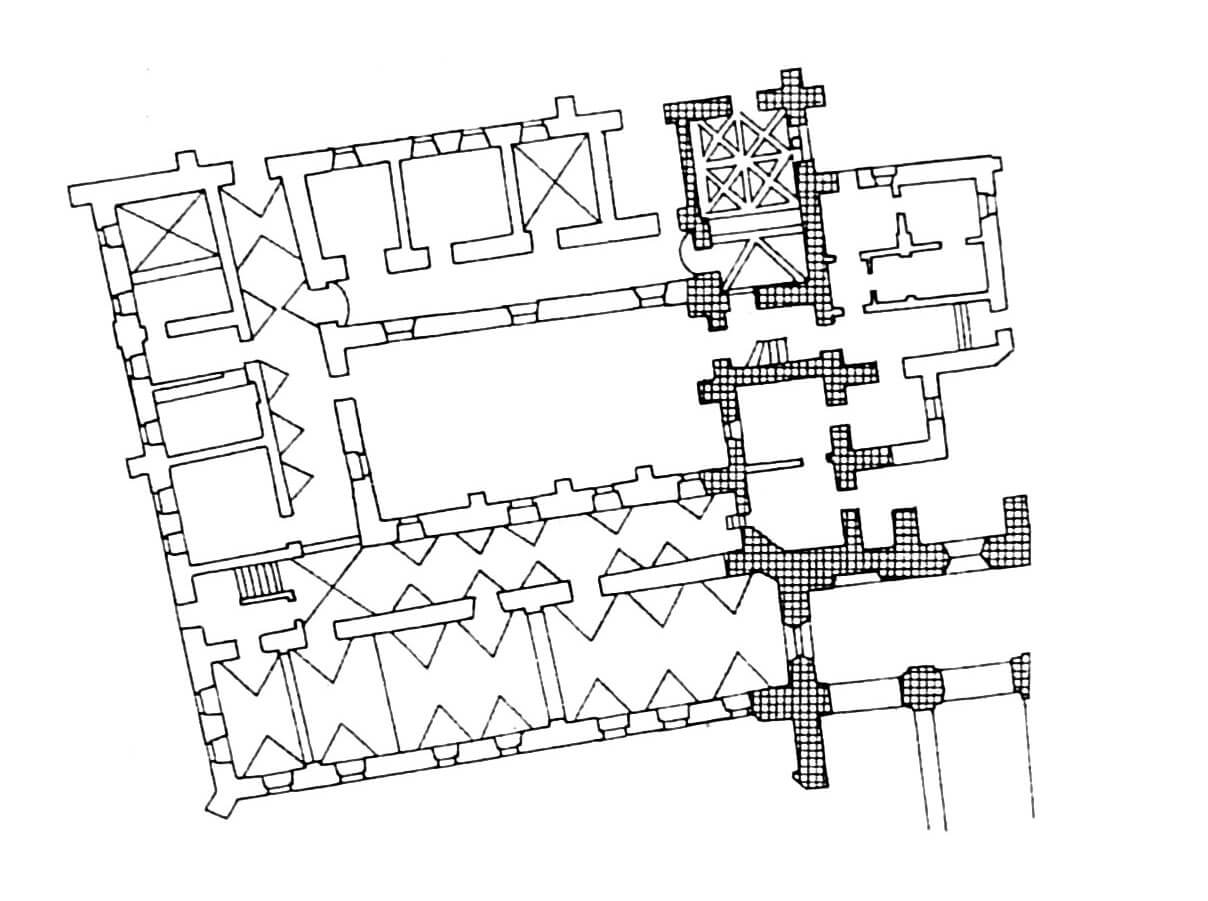

From the north-west, monastery buildings were attached to the church. Initially, it was a single, long, two-story house, adjacent to the corner of the northern aisle with its shorter side. Therefore, the buildings did not constitute a typical monastery quadrum with a garth in the middle, or in the Middle Ages, only the above eastern range had a brick form, and the rest were timber. In the brick building, one of the rooms, probably a former refectory, was covered over two bays with a late Gothic net and rib vault.

Current state

The Corpus Christi church is a unique building for the Wielkopolska region, because nowhere outside Poznań has such a long and high chancel connected with a pseudo-basilica nave of similar proportions appeared. The church has survived to modern times in a fairly good condition, as for Poznań Gothic buildings, which is mainly due to the small damages from the Second World War. On the other hand, considerable accusations are often made of the interwar renovation, during which the western and northern portal fittings and numerous fragments of the Gothic face of the walls were completely replaced. The former decoration of the church, stone tracery from the 15th century, survived only in three windows of the chancel . Unfortunately, all the gables of the church existing today are early modern, only the lower fragment of the eastern half-gable of the southern aisle has survived. Similarly, the original vault of the central nave, replaced in the 17th century, has not survived.

On the façade of the first bay of the nave from the east, there is a bricked-up ogival arcade with two segmental arches and an outline of the line of vaults and recesses. These are traces of the no longer existing Gothic chapel of the Three Hosts, replaced with an early modern chapel on the northern side of the church.

The monastery buildings near the church underwent a thorough reconstruction after the Swedish Deluge, when three more wings were probably added to the medieval east range, forming a regular quadrilateral. Currently, they have a modest, almost stylless character, with medieval vaults in only one room.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Kowalski Z., Gotyk wielkopolski. Architektura sakralna XIII-XVI wieku, Poznań 2010.

Kusztelski A., Kościół Bożego Ciała w Poznaniu, późnośredniowieczne sanktuarium, jagiellońska fundacja. Historia i architektura, “Nasza Przeszłość”, 94/2000.

Ratajczak T., Kościół Bożego Ciała w Poznaniu, Poznań 2014.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 1, architektura sakralna, Kalisz 2007.

Walczak M., Kościoły gotyckie w Polsce, Kraków 2015.