History

The defensive walls of Poznań were built around 1280 in the place of wooden-earth fortifications erected directly after the town location. By 1297, when the guards on the walls were mentioned, probably the majority of the work was done, but they could however continued in the 14th century. The work facilitated the size of the town, where already in the fourteenth century formed a team of building craftsmen. The construction of the walls and the castle was connected with the period of rule and the person of the prince, and later king, Przemysł II. He was an investor of fortifications, and it was only in the second half of the fourteenth or early fifteenth century that the fortifications became the property of the town and their maintenance became a concern of the townspeople.

The strength of the fortification was confirmed by the fact of repulsing the attack of John Luxembourg in 1331, during which the invaders were to lose 500 people and most of the siege machines. During the internal battles of the Grzymalites with Nałęcz families during the interregnum, the city (without the castle) was captured by the troops of the castellan of Nakło, Świdwa. The first known work on the modernization of fortifications was undertaken at the beginning of the 15th century. After 1411, they mainly concerned the cleaning of the moats. The most important investment of this period was, probably in the years 1431 – 1433, the construction of a second, outer belt of walls, which covered most of the perimeter from the west, north and south. In 1444, King Władysław III allowed the townspeople to buy the voigt office and gave the city 50 fines in order to expand the fortifications and dig moats. On repairs to the walls in the years 1493 – 1500, the Poznań authorities spent less than one fine a year, but more was spent on gates.

In the following centuries, the maintenance of the fortifications in a proper condition became the main problem for the city. In the 16th and 17th centuries, despite the devastating fires, wealthy Poznań was able to cope with the task, the more so because it acted with the help and encouragement of the monarchs. For example, the fortifications were rebuilt after a fire in 1536, during which 12 towers burned down, and after a fire in 1590, when King Sigismund the Old gave the city a mill called Bogdanka for 10 years. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the fortifications dilapidated, destroyed during the wars, so that during the Bar Confederation, the Russians had to supplement the defects in the wall with palisades.

Starting from the 15th century, defensive walls began to serve also non-military purposes. The first mention of the use of the tower on the mint comes from 1412, and for residential purposes from 1430. An example of the widely used adaptation of the towers was the reconstruction of three of them at the Dark Gate in the sixteenth century. With the process of rebuilding and using elements of fortifications for civil purposes, town council tried to fight. The defensive value of the fortifications was also weakened by the piercing of wicket gates, as well as the demolition of a significant part of the wall from the south, in connection with the construction of a complex of Jesuit buildings. The systematic demolition of the fortifications was initiated by the Prussians after the partitions of Poland in 1797. It lasted until the middle of the nineteenth century, but quite a few fragments of the walls were dismantled at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Architecture

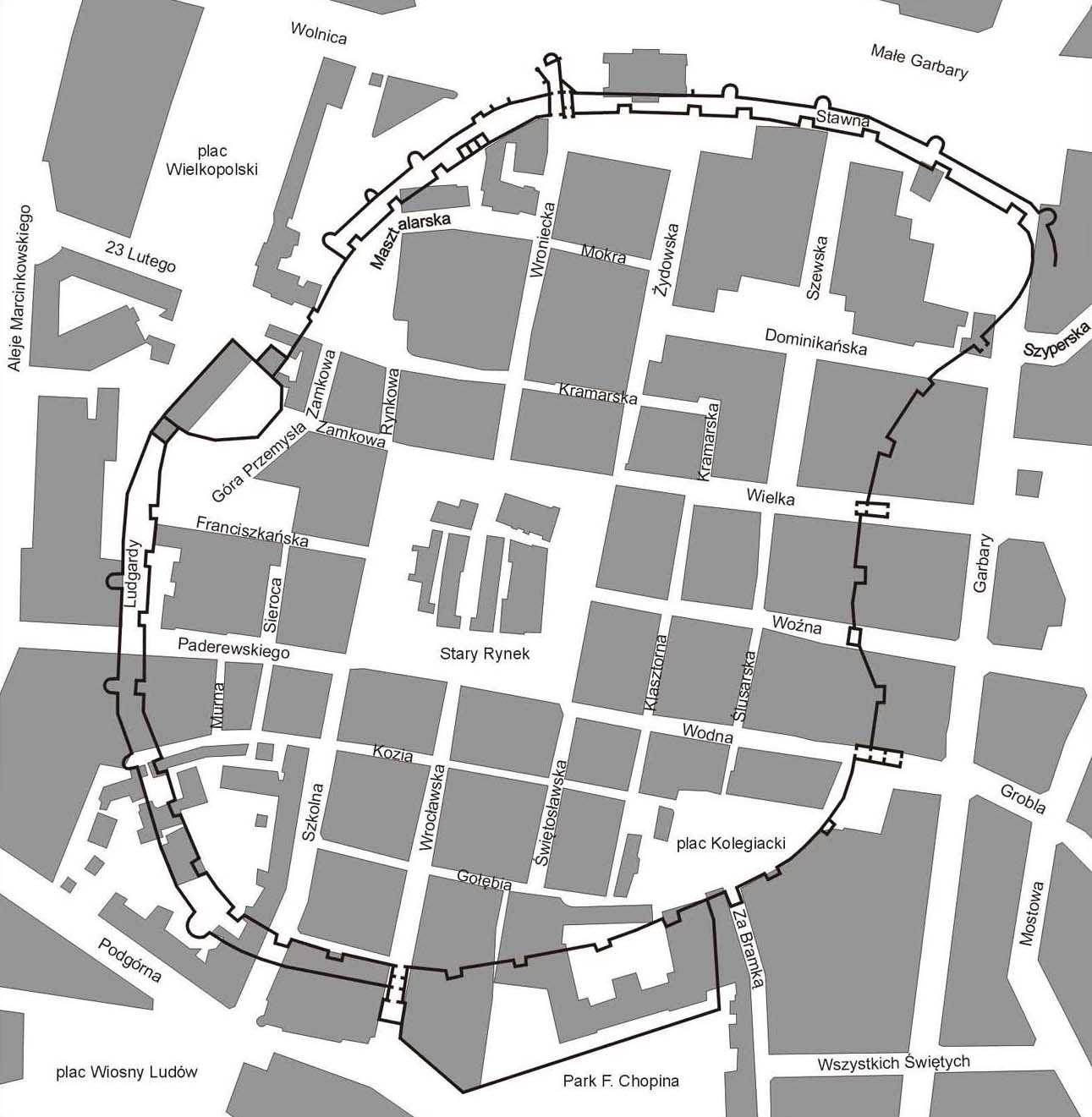

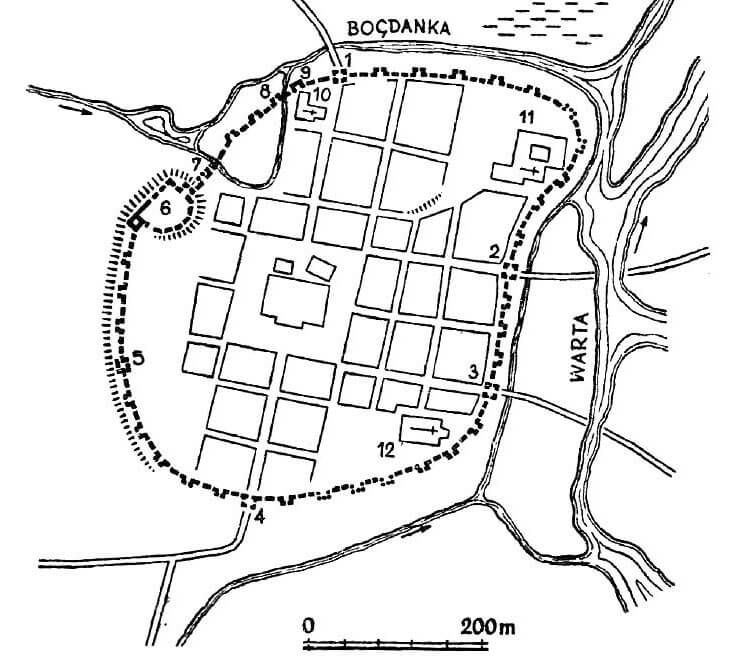

The perimeter of the defensive walls was approximately oval in shape, slightly elongated on the north-south line, adapted to the form of the terrain. Poznań occupied the area of the terrace of the floodplain of the Warta, bounded from the east by the riverbed, from the north by the lower course of the Bogdanka flowing into the Warta, and from the west by the slope of the castle hill. From the north-east, the line of walls bulged strongly to cover the earlier settlement of St. Gotthard. The eastern section was concave due to the course of the Warta valley. A slight flattening of the outline also occurred north of the castle and was related to the shape of the castle buildings earlier than the walls.

The area of the town within the walls was about 20 ha (about 500 x 440 meters), and the length of the fortification line about 1700 meters. From the town side, the walls surrounded a underwall street, whose course was interrupted only by a castle, occupying the western part of circuit. Immediately behind the underwall street, all the religious complexes of medieval Poznań were grouped: the Dominicans in the north-eastern part of the town, the Dominican sisters in the north-west and the parish church in the south-east. These buildings were so close to the wall that “only the paths divided them”. They could have additional defensive significance, in particular as observation points. The central point of the city was a market square from which twelve streets intersecting with two larger roads led towards the gates and walls.

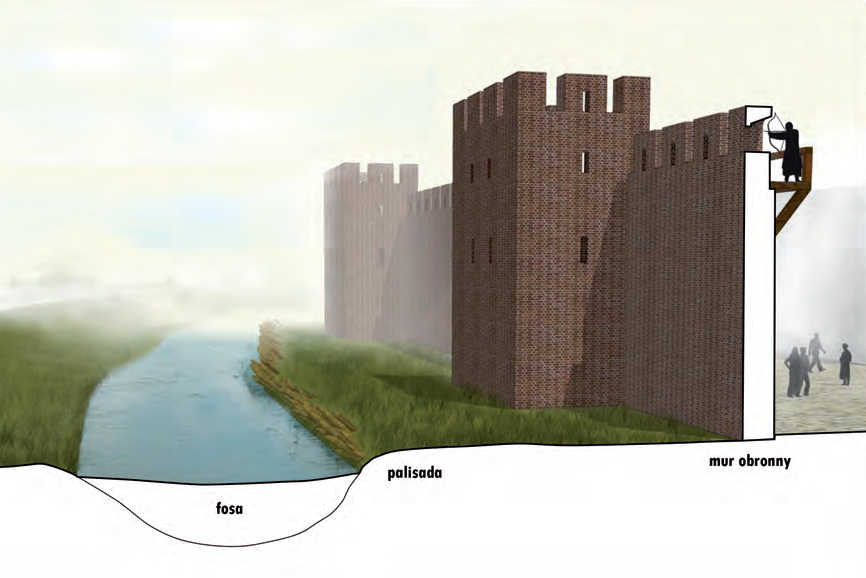

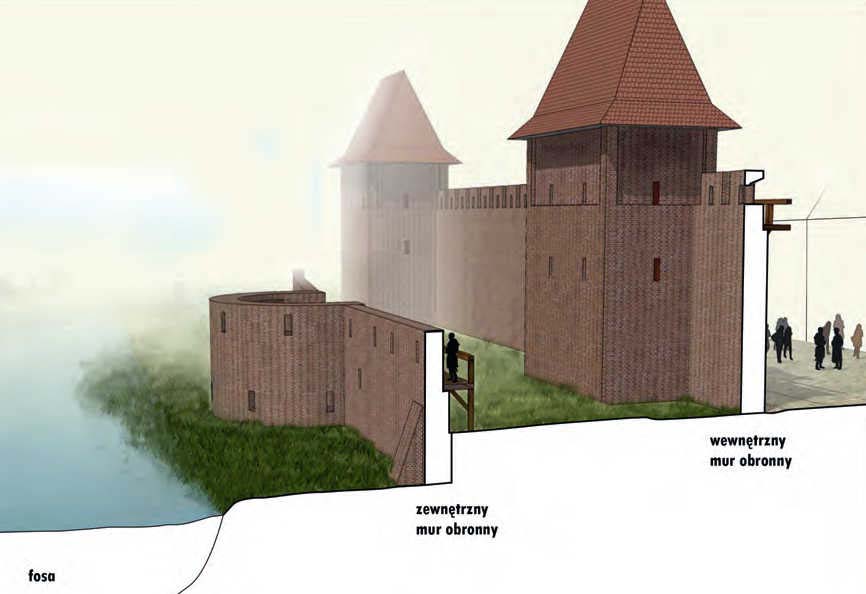

A defensive wall was built of brick tied in the monk bond and set on a stone foundation. It had a thickness of 1-1,2 meter. The height was, together with the battlement, probably more than 7 meters. It was crowned with a battlement, under which the defenders wall-walk ran from the inside. The merlons were about 2.1 meters long, and were separated by about 0.65 meters gaps. In the early modern period the crown of some sections of the walls was rebuilt. It received a simple closure, with a row of arrowslits below. Too little berm on a brick walkway required to be expanded with wooden platforms.

The wall was reinforced with about 35 identical towers, fairly regularly spaced around the circumference of every 35-45 meters. Their number and spacing put Poznań among the best fortified cities in Poland in the 14th century. The towers were rectangular in plan, extended in front of a wall. It were 7,60×5,35 meters and about 11 meters high. Were higher than the wall by one floor and open to the interior of the town. They were divided into four levels: ground floor with no arrowslits, the second floor with two narrow arrowslits in the front wall, the third floor corresponding to the level of wall-walk with two wider openings from the forehead. The third floor was based on a wider offset, which narrowed the wall to form a fourth floor – the battlement floor. It is not known whether it was with or without roof. Vertical communication took place with ladders, the third floor was probably connected by bridges to the wall-walk.

From the first half of the 15th century they were rebuilt. The earliest and most common way of remodeling was to close the originally open rear side of the tower with a new wall. Next to the half towers, in the south-west section of the wall, a square tower was located between the castle and the Wrocław Gate. It was extended on both sides in front of the wall, closed on all sides and much higher than other town defense objects. It was probably the primal one and it was the strongest point in the town fortification system. Similar objects were found in several other cities: Kalisz, Łęczyca.

Individual towers have been mentioned many times in documents. They were also determined, usually depending on the use by guilds (eg TailorTower, Shoemaker Tower), by the city (Town Tower), by church institutions (“Tower which the Virgins Hold”, “Tower that the Dominicans use”), or by private persons (Józefs Half tower). Often, the name of the street or other buildings was given (“The first tower from the Red Tower”).

The town had four gates. Wroniecka Gate from the north and Wrocław Gate from the south lay on the main axis of the route passing through the center of the market. The other two gates ran east: Great Gate crossing through Warta and Ostrów Tumski and Water Gate on the southern edge of the market. All the gates were probably primal, mentions about them appeared in the first half of the fifteenth century. Their architectural form is unfortunately poorly known. Probably housed in commonly used square or rectangular gatehouses, as we know it was for the Water Gate in the 15th century.

Gates were extended in various periods: upwards and forwards, in the form of foregates. The most powerful of which was created in front of the Wroniecka Gate. This is confirmed by historical views and plans of the town as well as several written accounts. The first alterations were probably made in the fifteenth century, including the construction of the external wall, reinforced with semicircular towers or bastions and external buttresses, built 9.4 – 9.7 meters away from the main wall (near the Wroniecka Gate). The foregate of the Wroniecka Gate consisted of up to three sections, 80 meters long and 6-7 meters wide, and was preceded by the backwaters of the Bogdanka River.

In addition to the main gates, there were several wicket gates for pedestrians in Poznań. These were probably simple passages, pierced in the wall mostly in the 15th-16th century, due to the expansion of the suburbs and various objects lying behind the walls. The earliest and perhaps the primal was the Castle Gate. It was under the cover of the castle and was the only exit from the town to the west.

The line of fortifications on the outside was reinforced by moats filled with water, brought from Bogdanka and the Carmelite stream. The first of these rivers flows around the town from the north west and north, entering the town with its bend, the second from the south-east and east, creating a parallel stream to the Warta river, closer to the town. From the south-west and the west, the moat probably was not originally, because digging the artificial channel on this relatively higher section would be very difficult and labor-intensive. It was also the only side that was additionally defended by the terrain. The rest of the moats were primal, as evidenced by references from the first half of the 15th century. Having built an outer wall, the defensive water system of Poznań has probably undergone further modification. Then, perhaps, the water ring was completed with a cross-cut from the south-west.

Current state

Until today have survived, fragments of the defensive wall at Ludgard street, a reconstructed section of the wall together with the “Firefighters” Tower and the Catherina Tower, the Gun Tower from the outer fortification ring and the southern part of the later outer walls near the former Wrocław Gate.

bibliography:

Banach B., Przemiany zabudowy miasta lokacyjnego w Poznaniu [in:] Civitas Posnaniensis. Studia z dziejów średniowiecznego Poznania, red. T.Jurek, Z.Kurnatowska, Poznań 2005.

Gostyński W., Pilarczyk Z., Poznań. Fortyfikacje miejskie, Poznań 2004.

Średniowieczny system obronny miasta Poznania. Odcinek północno-zachodni. Wyniki badań archeologicznych, red. P. Pawlak, Poznań 2013.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 2, architektura obronna, Kalisz 2011.

Widawski J., Miejskie mury obronne w państwie polskim do początku XV wieku, Warszawa 1973.