History

At the beginning of the establishment of the Pelplin abbey was a dispute between the Tczew prince Sambor II and the Cistercian monastery in Oliwa. The prince questioned the right of Oliwa monks to lands located in his district, especially in the fertile land of Gniew, and founding a new abbey was to be a counterweight to the abbots of Oliwa. Therefore, in 1258, Sambor’s nephew, prince Mszczuj II, brought the Cistercians under the leadership of abbot Werner from distant Bad Doberan in Mecklenburg. This decision could also be influenced by the Mecklenburg origin of Sambor’s wife. The monks were initially settled in the village of Pogódki, but in 1274 the prince donated the monks a new salary, granting them Pelplin, to which the monks moved two years later. The reason for translocation could be more favorable settlement conditions, more fertile lands, or less marshy areas. To emphasize the connection with the main abbey, the new seat was named Neu Doberan, but the local name Pelplin quickly adopted.

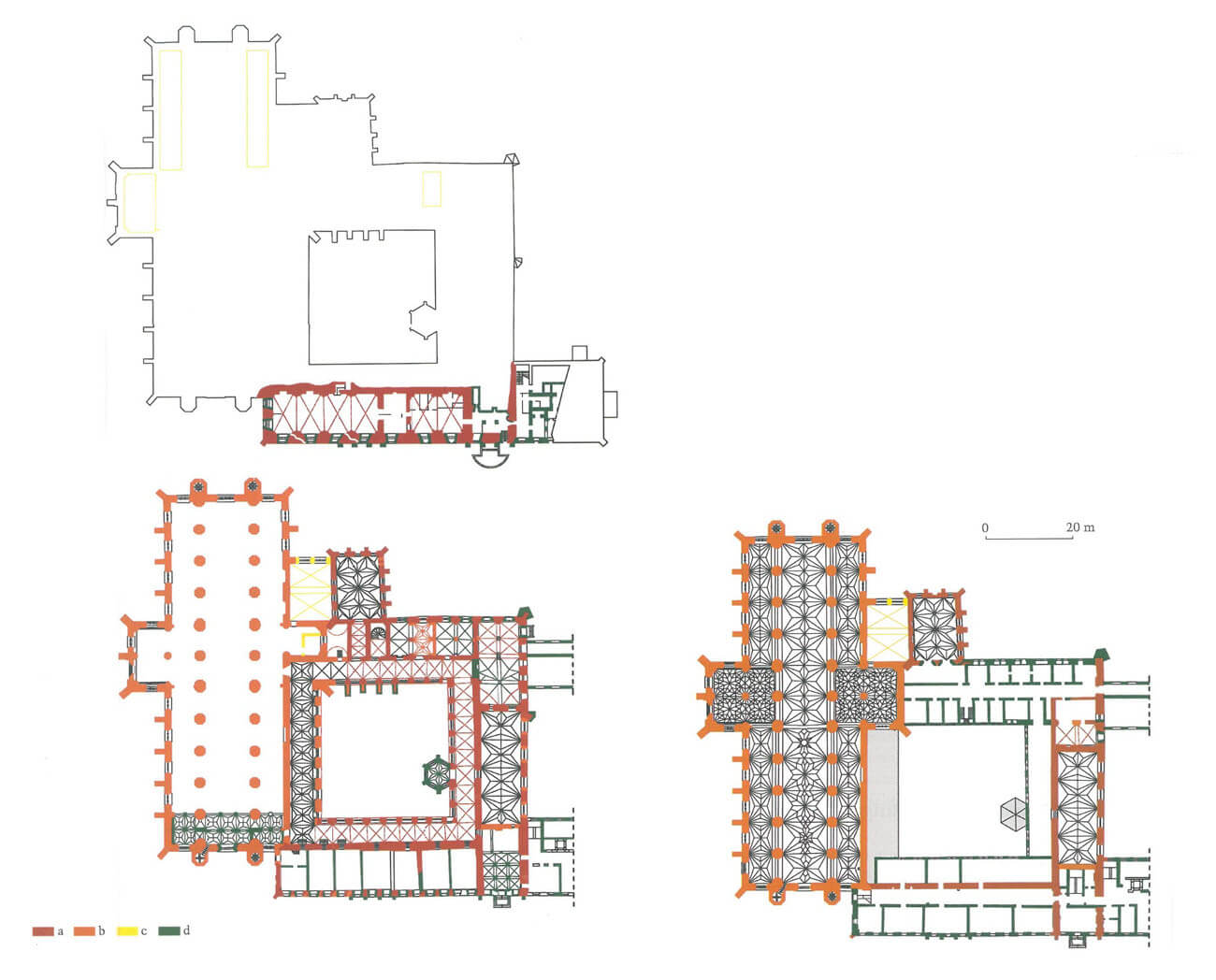

The construction of brick enclosure buildings probably began soon after the arrival of the monks to Pelplin between 1274 and 1276, with their size and location modeled on the native Bad Doberan Abbey (numerous toothing left in various places indicate that expansion was planned from the beginning). The first above-ground parts of the church were probably built in the second half of the fourteenth century, with the construction interrupted by numerous disasters, e.g. the collapse of the vaults in 1399 or the burning of the temple in 1433. Records comes from the years 1366 and 1377 about the acquisition of wood and stone by monks for construction purposes. In 1396, the Chełmno bishop Wikbold Dobilstein wrote in the will money for the construction of the church, we also know about indulgences from the 15th century, supporting construction works. At the time of the consecration of the main altar in 1472, the presbytery, central nave, central part of the church and southern aisle were completed. Finishing works, however, lasted quite a long time, and as their completion can be considered information from 1556 about the erection of the ridge turret at the crossing of the naves and about the year later completion of the transept vaults by the Anton Schultes from Gdańsk.

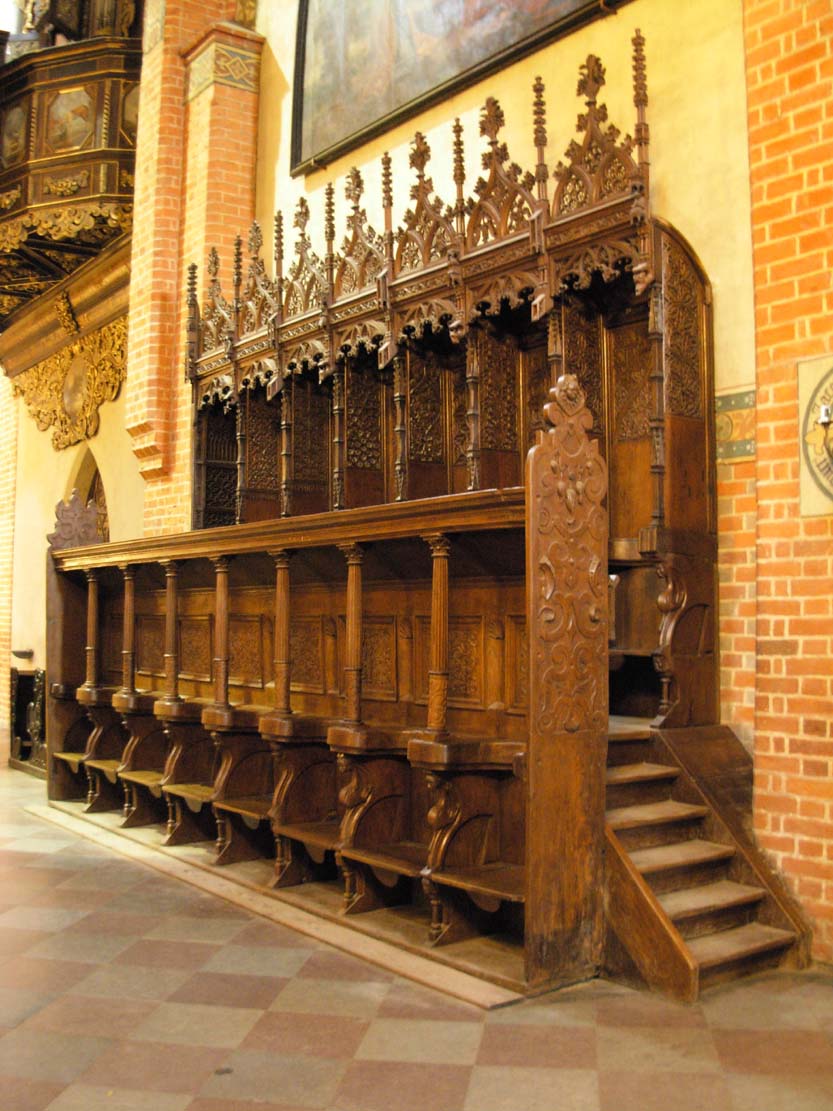

The abbey’s history was accompanied by a complicated political situation. In 1283, Pelplin was within the Teutonic state, while his possessions remained in the lands of Pomeranian dukes for a quarter of a century. Despite this, at the beginning the abbey received important privileges conducive to the development of its economy. In 1301, the monastery property was released from episcopal tithes, and from 1303 the abbey could founded its villages under German law. After the capture of East Pomerania by the Teutonic Knights in 1309, the Cistercians had to seek approval of their property and privileges. The situation stabilized only after 1421, when the Grand Teutonic Master Michael Küchmeister transferred the village of Pomyje to Pelplin Cistercians. Despite this, the end of the fourteenth and first half of the fifteenth century was a period of prosperity for the abbey, the time of two prominent abbots: Petr Honigfeld and Andrew of Rosenau was particularly marked by the increased activity of the monastery scriptorium. Documents, graduals, medical codecs were created there since the 14th century, the Bible and saint lists were also copied. An expression of the good condition of the abbey were also the elements of furnishing created in it, e.g. beautifully carved stalls from 1434-1454.

During the Polish-Teutonic war of 1410-1411, the abbey probably did not suffer any damage, although the Pelplin monks, due to the difficult situation, asked the Gniezno chapter for exemption from duties. In 1433, the monastery was ravaged and plundered during the invasion of the Hussites. All valuables were taken from the church, all the supplies were taken away and some of the monastery buildings were burnt. Leaving Pelplin, the Hussites set fire to the roof of the church, but it was extinguished by the local population. The difficult situation of the abbey was aggravated by the Thirteen Years’ War. In 1457, mercenary troops robbed the abbey, mill and bakery, killing two people. Further robberies took place in 1460 and 1462. From 1464, King Kazimierz Jagiellończyk took care of the abbey, confirming all previously granted privileges. What’s more, as compensation for losses incurred by the actions of mercenary troops, he donated 1,000 fines to the abbey.

In 1472, mostly completed monastery church was consecrated in the days of Abbot Sanderus, but two years later many monks died of the plague. The abbey also survived another crisis of the Reformation period, associated with an attempt to secularize order’s lands. At that time, it received help from King Sigismund I the Old, who prevented takeover by Protestants, in exchange for which the abbots were to pay for schools in Elbląg and Chełmno. In addition, from 1538 only Polish nobles could be elected to Pelplin abbots, and if there were no such monks, the king was to appoint a secular priest to this office. The last abbot chosen by the monks was a certain Szymon from Poznań, during whose in 1557 vaults were established in the church transept. In 1580, after the visitation recommended by the general chapter, the abbey was joined to the Polish Cistercian province, and twelve years later Mikołaj Kostka became abbot, who became famous for ordering income, built a new hospital, dormitory, refectory and infirmary for the sick.

The 17th century was prosperous for the abbey because of the Counter-Reformation that was underway, which resulted, among other things, in numerous donations from nobility and burghers returning to Catholicism. During this period, on the initiative of Abbot Rembowski, the interior of the temple was thoroughly made baroque, a prior house and a guest house were built. In the following years of the 17th century and the 18th century, despite numerous war contributions of the Northern War, crop failures and epidemics following them, the Pelplin Abbey was one of the most significant in Poland and was seen as a refuge of Catholicism in Royal Prussia. The situation changed completely after the first partition of Poland in 1772, as a result of which Pelplin was within Prussia. Prussian King Frederick II secularized church property, which caused the monastery to lose its importance and fall into debt. In 1810 the novices were banned, and in 1823 the order was dissoluted by Frederick William III. Although the former abbey lost its monastery character at that time, it retained its sacred function, because the capital of the territorially reorganized Chełmno diocese was moved to Pelplin, the monastery church was raised to the status of a cathedral, and a seminary was created in the place of the enclosure buildings. Due to the new function, the entire monastery complex has undergone extensive renovation and rebuilding, carried out in neo-Gothic style from the 1840s to the end of the century. During the Nazi occupation, the cathedral was closed, the seminar was reorganized into a police school and a prison, and Pelplin professors and canons were murdered. Fighting in 1945 caused some of the stained glass windows to break down in the church. Fortunately, the only bomb that fell into the building did not explode, but only damaged the roof and the vault.

Architecture

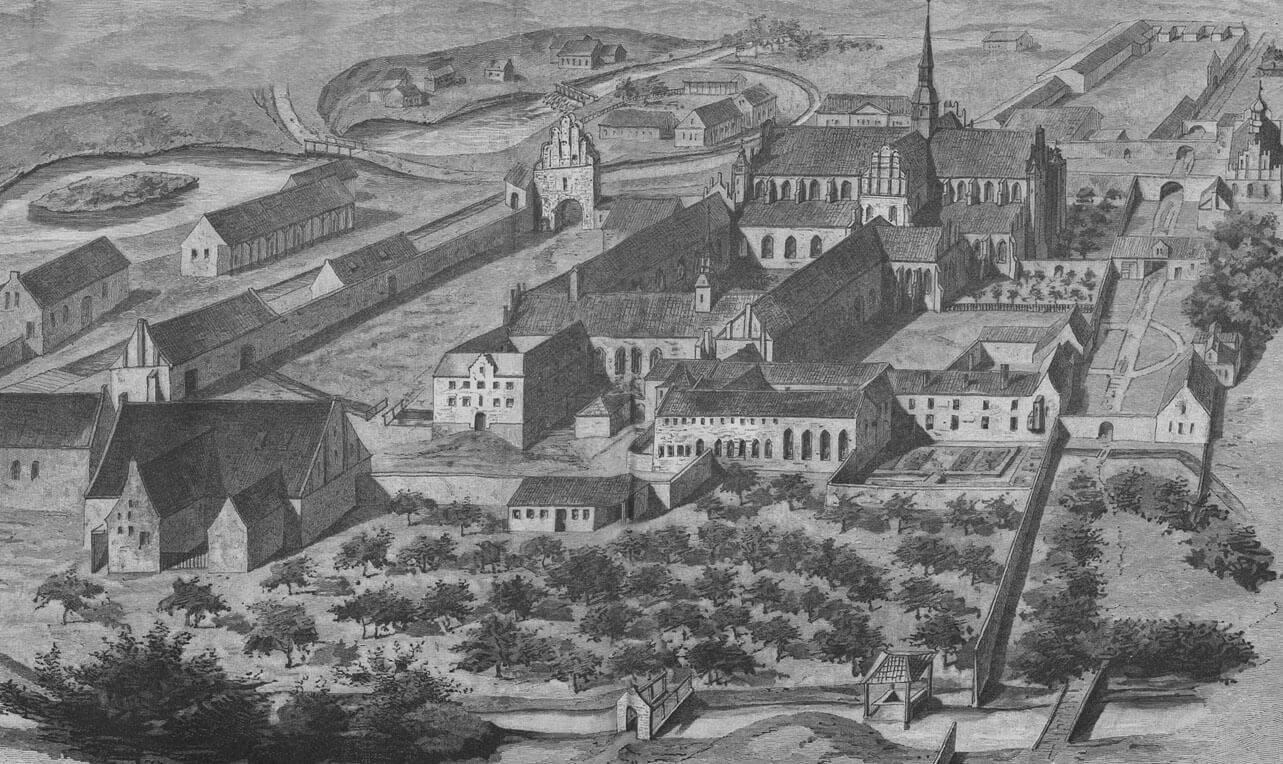

The abbey was erected on the left bank of the lower Wierzyca, in a small valley surrounded by low hills. Wierzyca in this section flowed along the north-south axis, but with numerous meanders. One of the larger bends was chosen for the foundation of the abbey, so that the river surrounded the monastery complex from the west and south, and at a slightly greater distance from the north. Near the abbey there was a local trail crossing Wierzyca, leading to Starogard in the west.

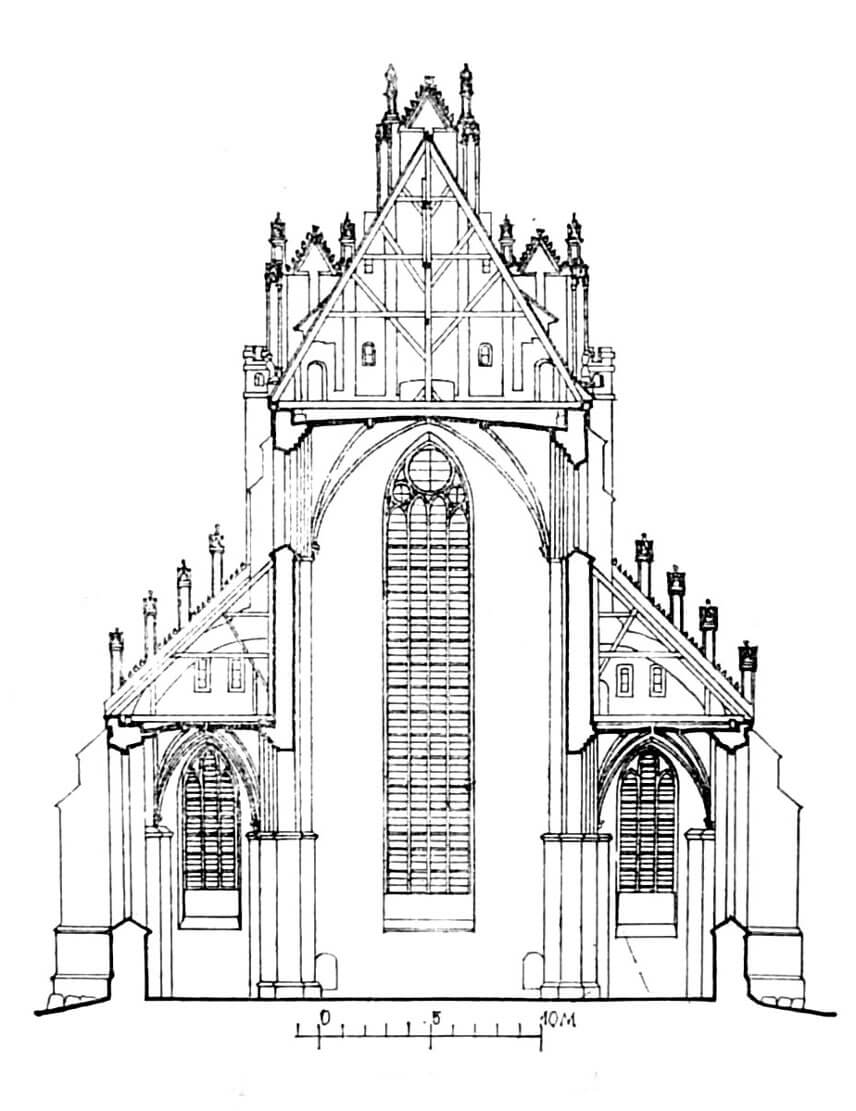

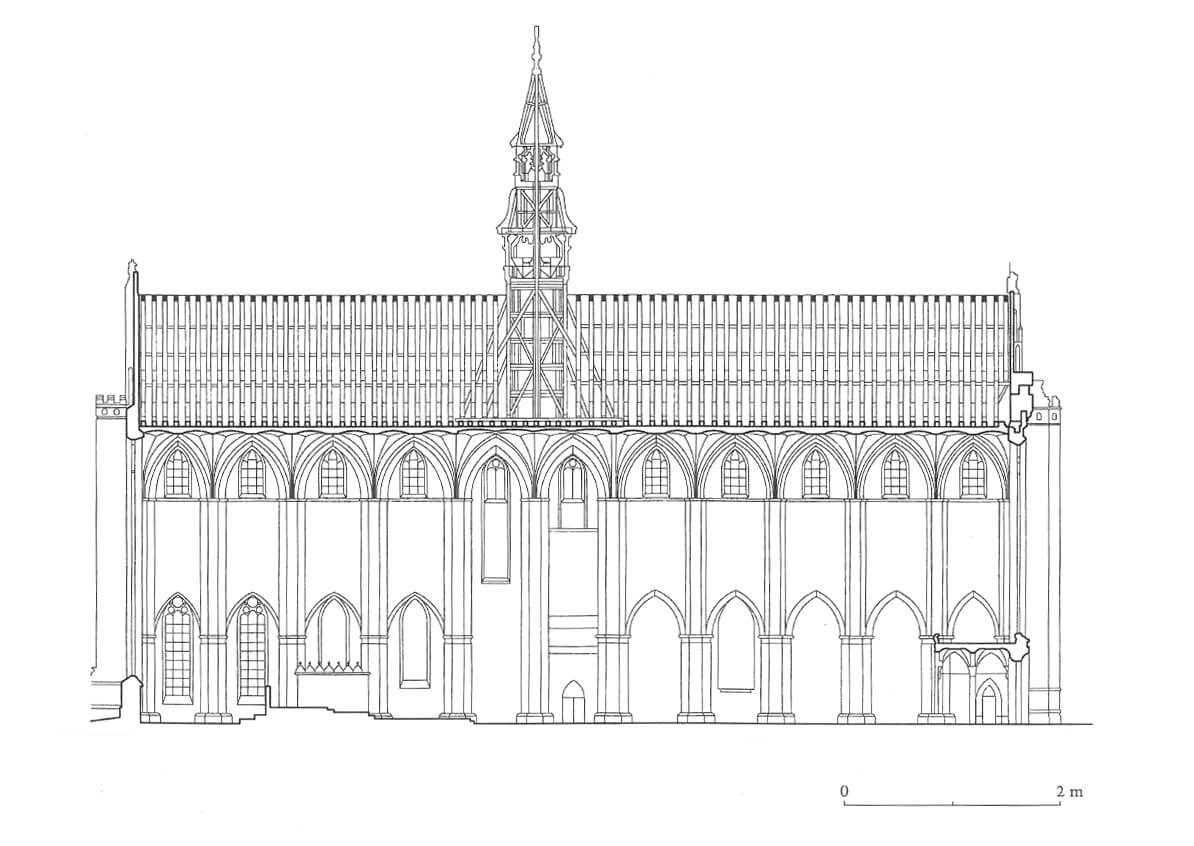

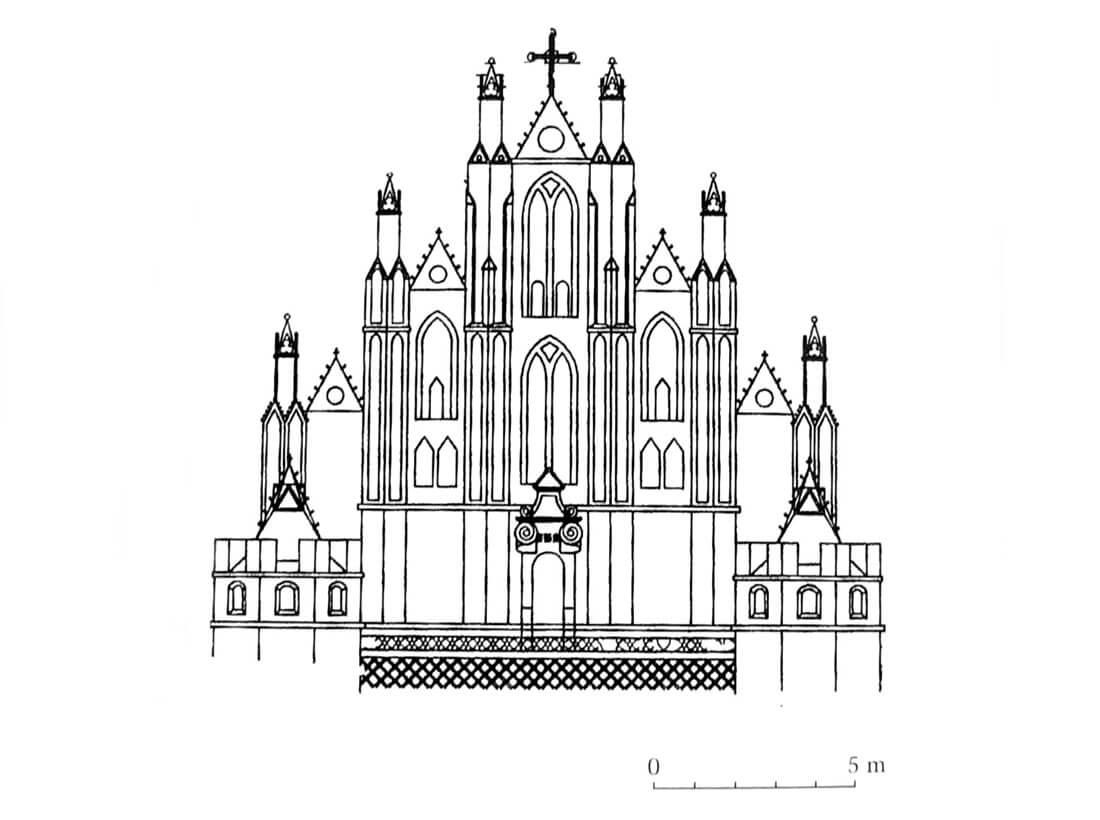

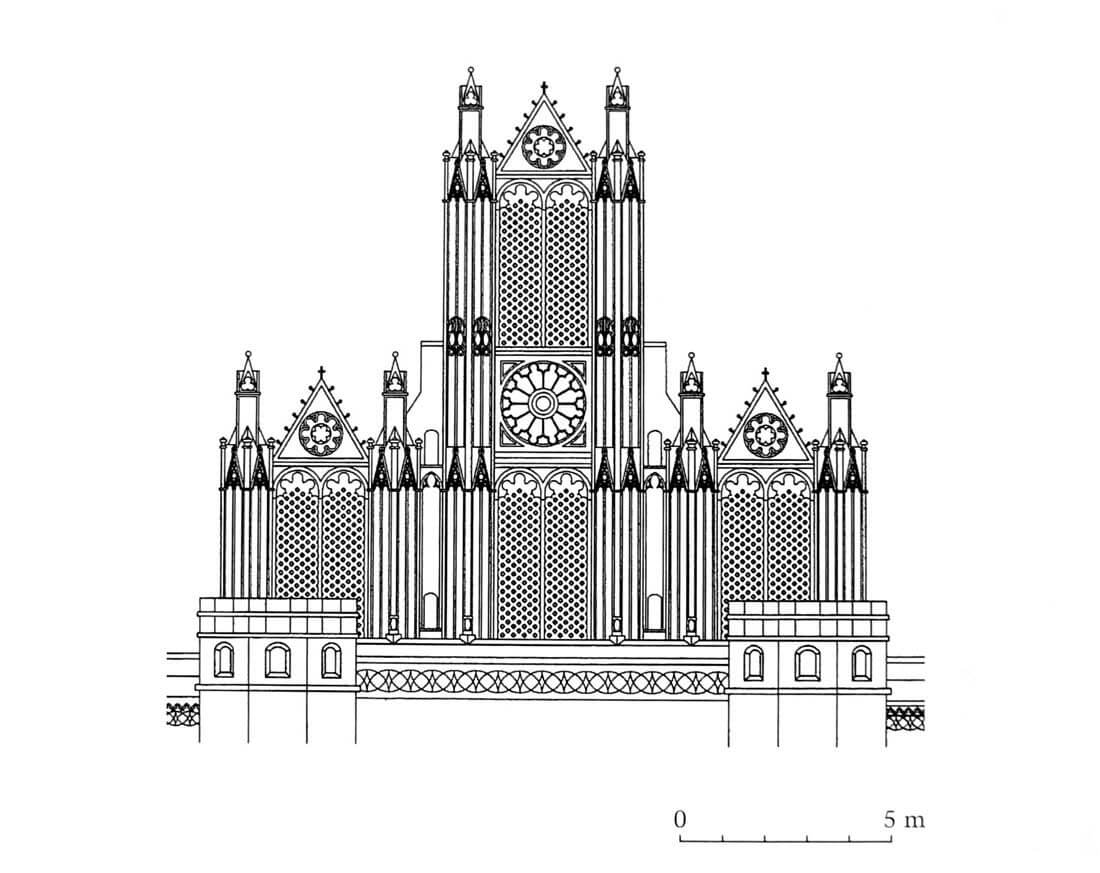

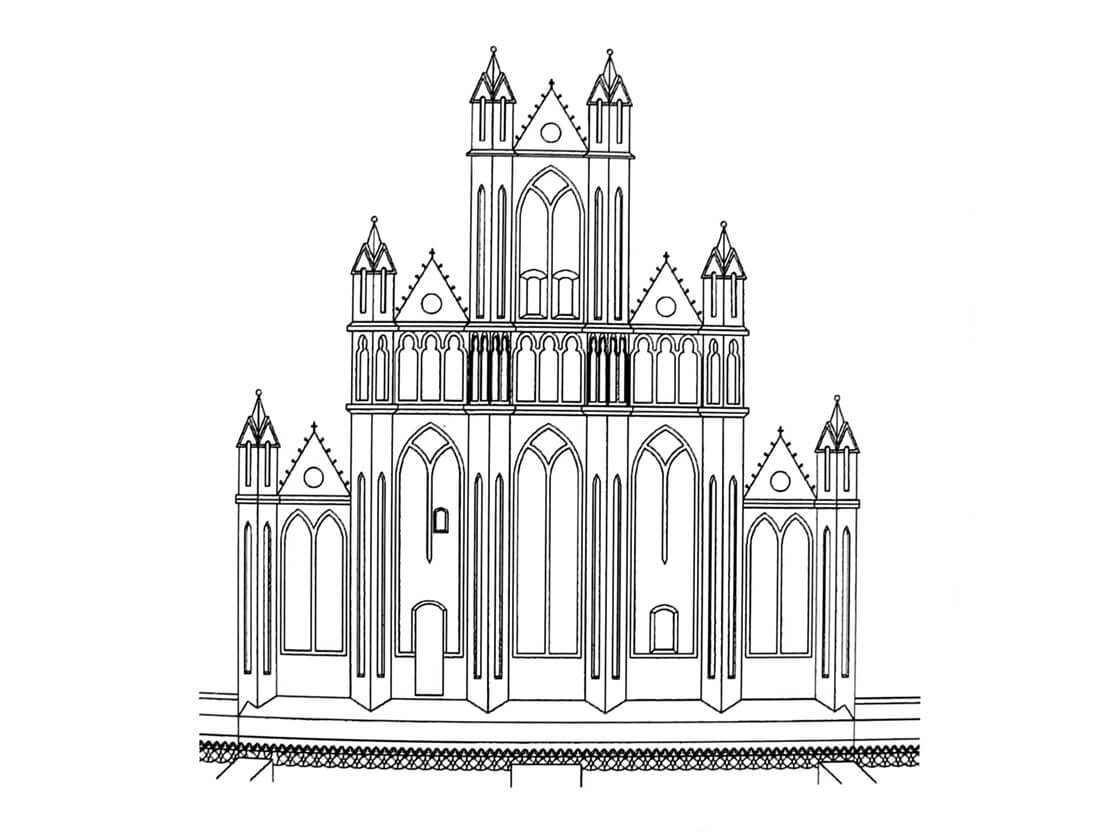

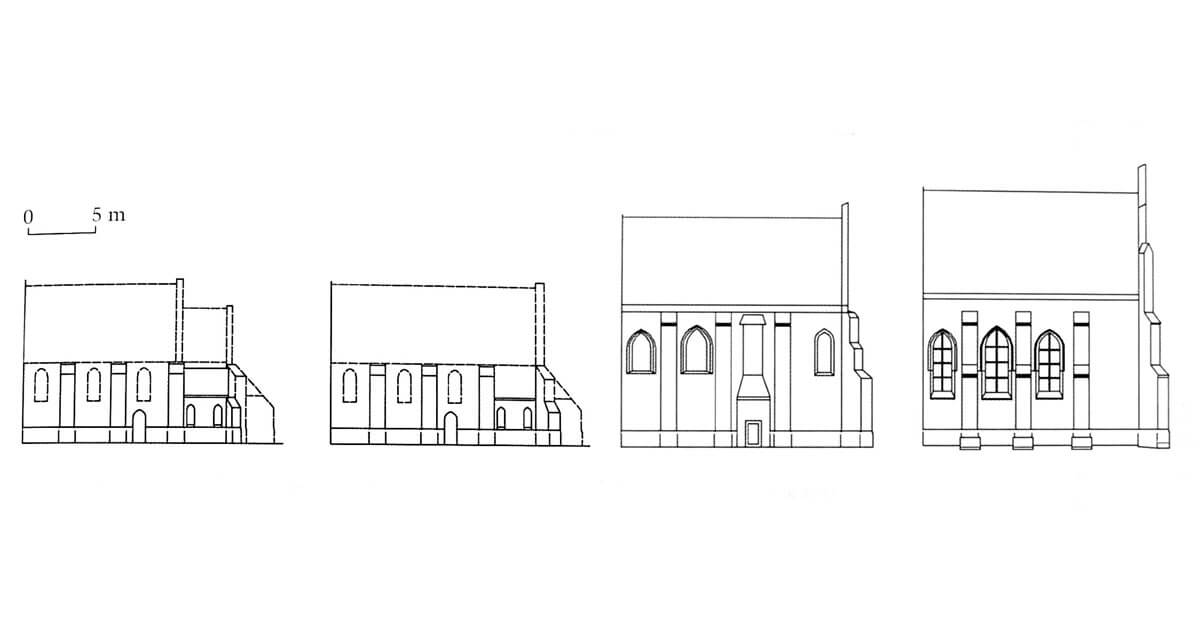

The monastery church was built as a magnificent three-aisle basilica on the plan of a Latin cross, with a five-bay nave, a two-bay transept of a hall arrangement consisting of two aisles and a four-bay, rectangular chancel, which flanked the aisles. The chancel was planned differently from the Doberan’s church one (where an ambulatory and wreath of chapels were used), giving it a form very similar to the western part of the church, differing only in the number of bays. Similar stair towers and the same basilica structure were used for the facades of the eastern and western parts. The length of the church was finally 83 meters, the maximum width was 45.6 meters, and the height of the nave and transept reached 26 meters, thanks to which the church in Pelplin was in Teutonic lands only second in size to St. Mary’s Basilica in Gdańsk.

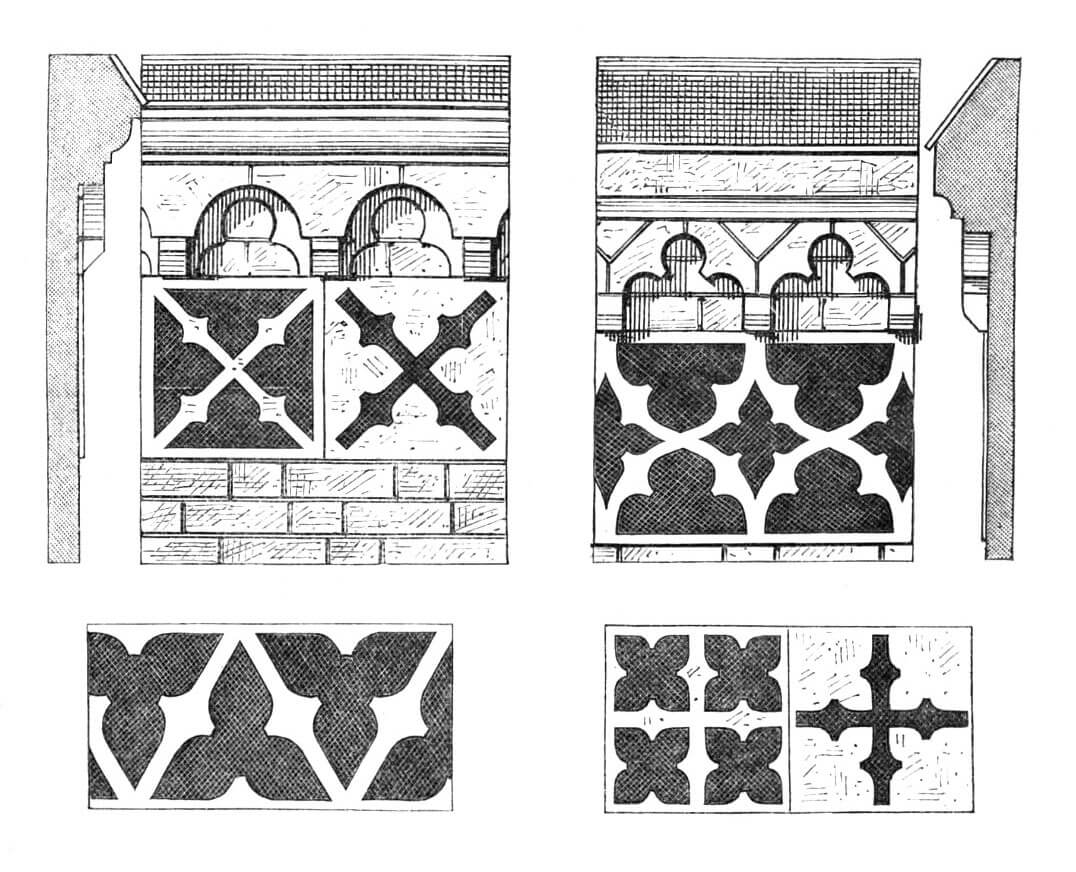

Outside, the walls of the temple were strengthened with buttresses, the structural system was also strengthened by flying buttresses, invisible to the naked eye, hidden in the roofs of the aisles. The facades were decorated with zendrówka bricks, crowned with arcade friezes and friezes with a quatrefoil motif. The front walls of the transept, and the west and east facades were crowned with richly decorated stepped gables. The aforementioned characteristic low octagonal stair towers flanking the façade of the central nave were also attached to the walls of the eastern and western elevations. They performed communication functions with attics, and at the same time replaced the buttresses, perhaps being part of the ideological militarization.

Entrances to the church led from three sides: from the west, north and south – from this last side two stepped portals led to the cloisters. The portal leading to the northern transept, or Porta Mortuorum, so-called because it originally led to the church cemetery, was richer. It was decorated with brick fittings and archivolts made partly of brick and partly of artificial stone, covered with relief carved decorations of angels and saints. The outer, most decorative archivolt was given the shape of an ogee arch fashionable in the late Middle Ages (tympanum is already a conservation creation from the 19th century). It was decorated with friezes with floral and geometric motifs. In the capitals of the portal there figures of prophets were set, above them figures of apostles and saints. Two external figures were placed under Gothic canopies.

The architecture of the interior of the transept’s arms is different from the rest of the church due to the diamond and net vaults used there, because the remaining parts of the temple were covered with a stellar vaults. The latter received different forms in the presbytery and different forms in the nave. The vaults were supported by octagonal, based on pedestals, inter-nave piers, which at the height of the walls of the nave were partially embedded in the face of the walls, creating ogival, moulded arcades. Vault ribs were also mounted on ceramic corbels with geometric and anthropomorphic motifs in the form of heads, busts, figurines of atlants and zoomorphic representations (e.g. sphinx, dragon, harpy, mermaid). The window zone was located high above the cornice, over which the walls of individual bays took the ogival form. The higher walls of the presbytery and the central nave were reinforced with moulded archs on which the vault bows were based, while in the lower side aisles wall bows were abandoned and in this way half-pillars were created ended in the places of the vaults beginnings. The purpose of this was to save building materials.

The southern part of the transept which is in contact with the monastery’s buildings was not well planned. In this place, the south-west bay became part of the cloister, which was unfavorable for structural reasons and could have contributed to the construction disaster. For this reason, the southern gable had to be repaired, and massive buttresses were set up in the corner of the cloisters garth and east wing to prevent cracks.

In the medieval church there was rich furnishings, among which were important benches for monks, abbot and celebrant. These wooden stalls with 42 seats were decorated with sculptures with architectural, animal, floral, tracery and figural motifs. Each seat was separated from the next by an openwork wall and topped with a fancy gable in the shape of a ogee arch. The motif for the decoration of the stalls were biblical scenes, fragments from the lives of saints and from Physiologus, the predecessor of later encyclopedias. The stalls were placed in the eastern part of the church, intended only for monks. For lay brothers and ordinary people, only the western part was available, separated by rood screen on the border of the third and fourth bays of the nave. Celebrant stalls were located at the main altar, stalls of monks in the central nave of the presbytery, and stalls of sick monks at the rood screen.

Adjacent to the church from the south, the enclosure complex was integrated with the cloisters surrounding the four-sided patio. Three of the cloister wings were covered with cross vaults with pear-shaped ribs, falling on the corbels with a predominance of figural (eastern cloister), tracery (southern cloister) and floral (western cloister) motifs. The northern, youngest part of the cloisters was covered with a stellar vault. It also received a greater width than the others (5.8 meters). In the fourteenth century, the cloister walls were covered with polychromes.

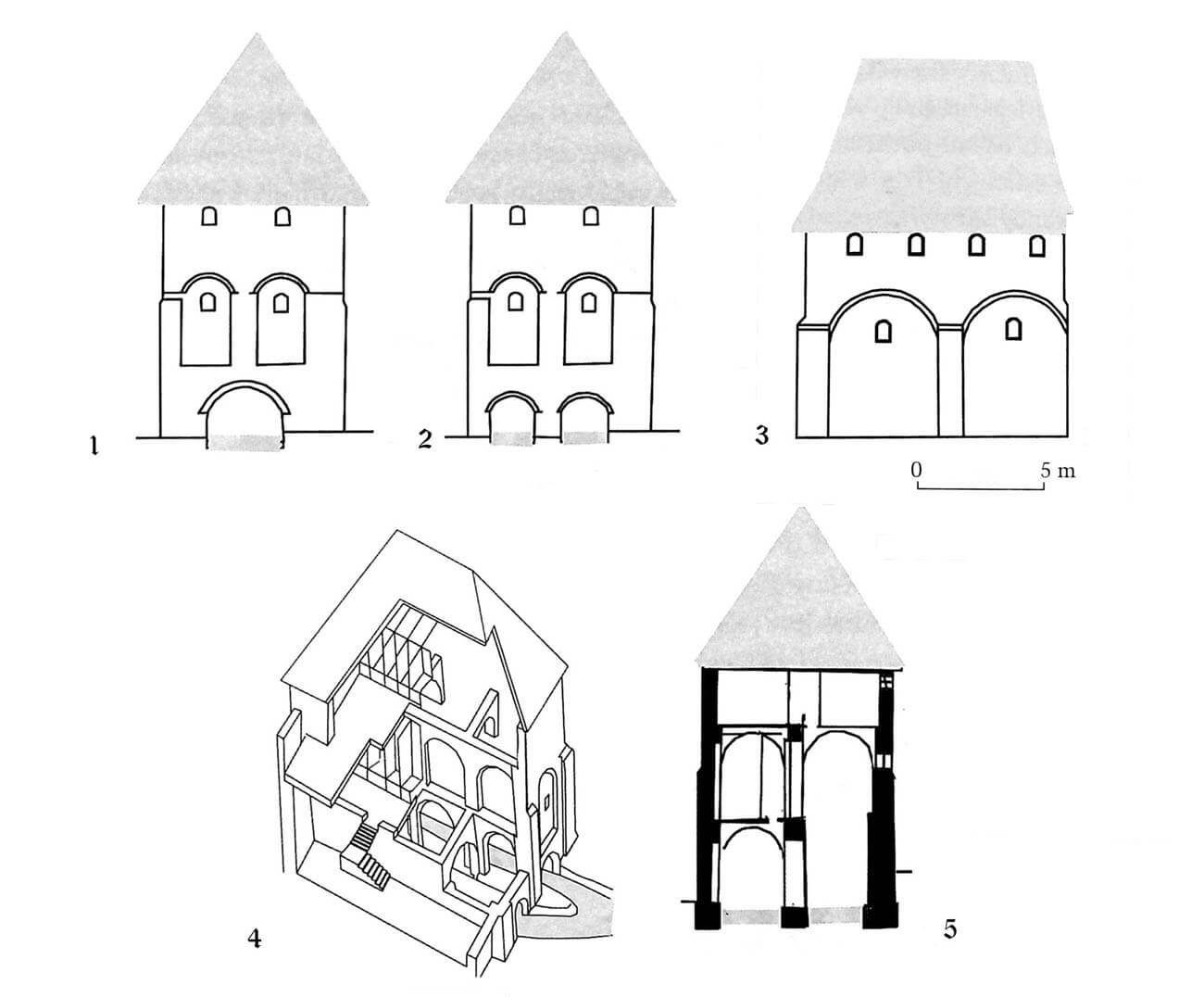

The oldest and most important eastern wing of the enclosure was located on the south side of the church transept. Its 13th-century oratory building (today’s Chapel of the Holy Cross) protruded from its rectangular building, which served as a monastery temple until the completion of the main church. After the church took over the sacred functions (probably in 1472), the oratory took over the role of chapter house and was crowned with a Gothic stellar shaped vault supported by three pillars and wall shafts. It was adjacent to the sacristy from the north, and connected to the cloister from the west by a vestibule. Next to the vestibule there was a staircase leading to the first floor of the east wing (perhaps with a prison underneath), and then in the middle of the wing the original chapter house was located, i.e. the abbey hall in which the brothers and the abbot discussed the most important matters of the monastery every day. After the chapter house was moved to the oratory, a two-bay vestibule with a stellar vault was created in its place. The last rooms of the east wing were probably the entrance lobby and the fraternity in the south, i.e. the place where the brothers worked, usually in the winter (fraternities in Cistercian monasteries were most often scriptorias). Its vault was based on massive stone, round columns with a flattened base, a thick shaft and cube-chalice head.

Traditionally, the entire upper floor of the east wing was occupied by a brothers’ dormitory, initially probably without partition walls. Probably in the thirteenth century, the monks’ mattresses were lying along the walls, and in the middle there was a free place providing communication with the northern transept of the church, where the brothers went to night and morning prayers. Lighting was provided by numerous, but small windows, on one side above the cloister roofs, and on the other to areas outside the enclosure. Separate cells were introduced in the dormitory in 1597.

The medieval southern wing from the east housed a calefaktory (warming room). It was the only room heated in the winter in which the scribes working in the nearby scriptorium were heated, and in which for the alleged health purposes blood was dropped. It was covered with a rib vault, lighting was provided by a small window from the south, and the fireplace gave heat – maybe two-sided, similar to that used at the castle in Malbork or in the Welsh abbey of Tintern. In Pelplin, it could heat the refectory adjacent to the west in addition to the calefactory. The refectory was originally a two-bay and two-aisle hall, perhaps covered with a rib vault supported by two columns (similar to a fraternity). Probably in the first half of the fifteenth century, due to the increase in the number of monks, the refectory was rebuilt. At that time, the vaults in the ground floor were demolished, the rooms on the first floor were liquidated, and the obtained long and high space was filled with a new four-bay room with a stellar vault. Its ribs were based on corbels carved like human heads and tracery decorations. The refectory was adjacent to the kitchen on the west side, probably filling the entire remaining part of the southern wing and characterized by a massive chimney known from old vedutas. From the north, in front of the entrance from the cloister to the refectory, there was lavabo, a kind of washroom in which the monks cleaned their hands before meals. It was enclosed by a polygonal, Gothic annex, probably similar to the one from the monastery in Osek. The southern part of the enclosure, exceptionally for Cistercian monasteries, was in Pelplin a two-story building with novitiate rooms on the first floor.

The west wing of the enclosure protruded its width in front of the west facade of the church and joined on the opposite side with the kitchen in the south wing. For this reason, it can be assumed that in that part it housed a refectory intended for lay brothers working on Cistercian farms. In addition, the ground floor of the west wing served as a warehouse and a monastery pantry – a cellarium, and the floor probably was a lay brothers bedroom. Interestingly, it was illuminated only from the outside, and from the side of the inner patio there were no windows. In the fourteenth century, the usable space of the wing was increased by inserting an additional, third floor, by raising the walls by 1.5 meters and lowering the ground floor level by about 1.2 meters. The only room on the former level remained a vestibule, at which basements were partially embedded in the ground, covered with rib vaults. The southern basement was two-bay and the northern four-bay, while the stairs led to the cloister from the vestibule. The second entrance was probably in the west wall. Above the southern basement there was still a lay brothers refectory with a niche in the wall and a opening for serving food from the kitchen. The highest floor was occupied by a lay brothers dormitory with a number of niches topped with segmental arches, probably intended for placing lighting (e.g. olive lamps, candles).

A latrine building protruded from the compact enclosure complex to the south, located above the canal and connected to the south wing by a covered porch. Its facades were divided into two parts in the ground floor with lesene-buttresses and semicircular bows. In the higher parts, the building was varied only by small windows topped with segmental arches. In addition, a wide opening remains in its western wall, probably leading to the channel under the building. In the fourteenth century south-east of the enclosure, on the canal a new building was erected with the chapel of St. Barbara, with its corner added to the latrine building. It probably housed a hospital noted in written sources.

In addition to the buildings centered around the cloisters, economic buildings with a brewery, malt house and granary were erected in the western part of the monastery complex, and a small Corpus Christi Church in the northern part, which probably stood on the site of the former monastery gate. The whole abbey was located in the bend of the Wierzyca River flowing from the west and south. It was important for the daily functioning of the monastery, the channel supplying Gothic mills and cleaning latrines was dug out of it. The large and small mill was located on the south-west side. The monastery was also surrounded by a wall within which two gates led, including the main one with the tower and the gatekeeper’s apartment on the north-west side.

Current state

The Pelplin Abbey belongs to the group of the most important monuments of Gothic architecture in Poland. It owes it mainly to the monastery church, as well as the early Gothic oratory, i.e. the later chapter house (today’s Holy Cross Chapel), one of the oldest in Gdańsk Pomerania, or the preserved cloisters with a moulded portal leading to the chapter house and wall paintings from the 15th century. The church has original spatial layout, while most of the architectural details have been renovated or replaced (window traceries, gables, cornices, some window jambs).

Unfortunately, most of the claustrum buildings were transformed during a thorough neo-Gothic reconstruction. The medieval walls have been preserved at the level of the first floor only in the southern wing. In the ground floor, the original or close to the original layout of the rooms has been preserved in the east and south wing, while the west wing was divided into new rooms, leaving the original division only in the basement. Today, modern buildings also stand on the site of medieval buildings on the southern and eastern side of the claustrum. Most of them have been removed, only the old latrine building has been partially preserved.

The church, cloisters with an inner garth, and the chapel of Holy Cross and cellars under the west wing are available to visitors. The other rooms are not accessible to tourists. You can only enter the Gothic, but rebuilt gatehouse and the mill building from the fourteenth century, where public institutions and service premises are located.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Ciemnołoński J., Pasierb J., Pelplin, Wrocław 1978.

Die Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler der Provinz Westpreußen, der Kreis Pr. Stargard, red. J.Heise, Danzig 1885.

Grzybkowski A., Gotycka architektura murowana w Polsce, Warszawa 2016.

Łużyniecka E., Pelplin i Doberan : architektura opactw cysterskich spokrewnionych filiacyjnie, Wrocław 2014.

Walczak M., Kościoły gotyckie w Polsce, Kraków 2015.

Wyrwa A.M., Opactwa cysterskie na Pomorzu, Warszawa 1999.