History

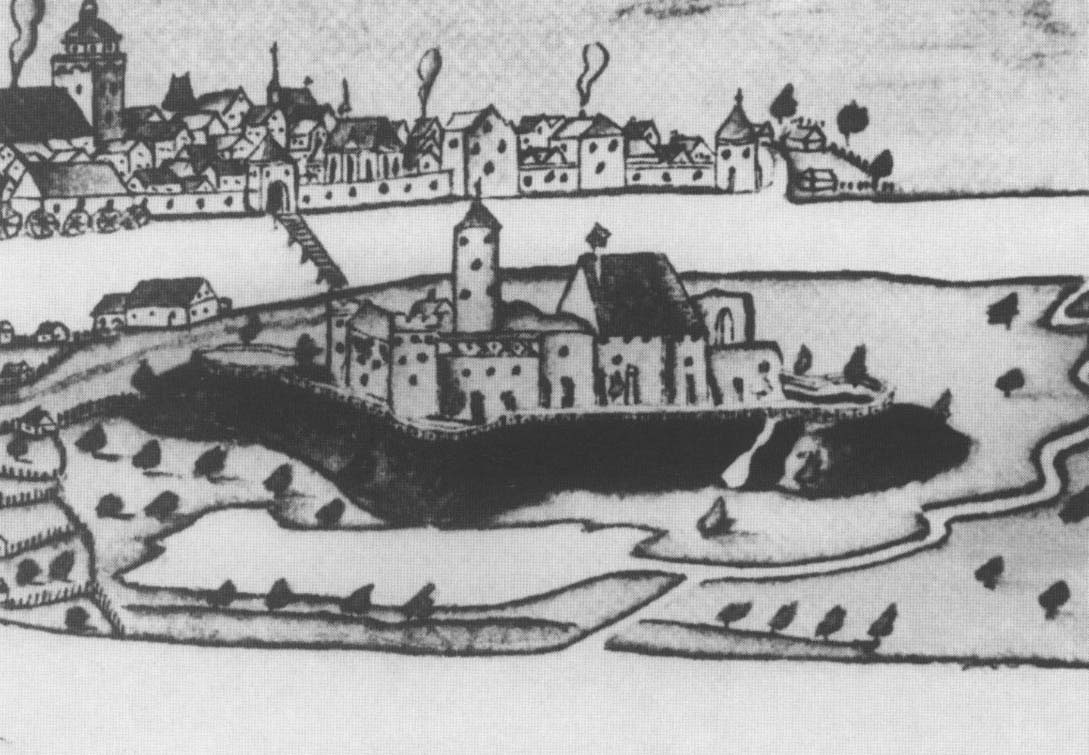

The construction of the castle began on the initiative of Prince Kazimierz I in 1228, as one of the oldest brick strongholds in the Piast dynasty domain. It was built on the site of an old stronghold of the Opole tribe, which had existed on the Odra island since the end of the 8th century. In the times of the Piast’s monarchy, the stronghold was one of the most important centers in Silesia, and from the moment of the fragmentation of the realm it was associated with the titularity of princes. In 1198, in document the Bishop of Wrocław, Jarosław, son of Prince Bolesław the Tall, was called “dominus de Opol”, while in a document from 1215 and in another privilege for the inhabitants of Leśnica from 1217, Prince Casimir I used the term “dux de Opel “.

The founding of a town on the right bank of the Oder River by Kazimierz I in the years 1211-1217, on the site of a market settlement, resulted in the relocation of the inhabitants of the timber stronghold from Pasieki Island to a new place, thanks to which the construction of a castle could be started on the tip of the island called Ostrówek. Its castellan, Klemens of Ruszcza, and his brother Wierzbięta agreed to share the burden of works with the prince, in exchange for nine villages and other profits. In 1228, the replacement of the wooden buildings with brick ones began, and the construction of a defensive wall in place of the earth ramparts. The main construction works were completed around 1260, in the times of Kazimierz I’s son, Prince Władysław I, when the nunnery in Staniątki near Kraków was released from the obligations of participating in the construction.

Work on the expansion of the castle was continued by the founder’s grandson and son of Władysław I, Prince Bolesław I, who built the main castle house in the years 1283-1289. In a document from 1289, he donated 100 Frankish lans to the monastery in Czarnowąsy, located in the forest next to the Opole castle, then called “new”, which probably referred to the recently completed representative house. Then, around 1300, on the initiative of Bolesław I, a cylindrical Piast’s Tower was built, and in 1307, the bishop of Wrocław, Henry of Wierzbno, consecrated the castle chapel dedicated to John the Evangelist, the apostles Peter and Paul and Mary Magdalene, for which he donated a tithe from the village of Niewodniki. Prince Bolesław also donated 6 lans for the chapel in Gosławice. During the reign of Bolko II, the castle was enlarged by a house with a burgrave’s apartment.

The castle was the seat of the Opole Piasts dynasty until the death of its last representative, John II the Good in 1532. On this occasion, the imperial commissioners of Ferdinand Habsburg, who then became the owner of Opole, made a list of the castle inventory. According to it, in the armory there were 13 armours, 3 helmets, 28 halberds, 260 landsknechstowskich javelins, 57 old handcannons, 23 new handcannons, 77 large handcannons, 34 new javelins and 14 forms for casting missiles. In addition, in the prince’s bedroom there were two beds with quilts, sheets and pillows, a table, two benches, a trunk and some glowing stone. The treasury had 600,000 florins, many valuables, 10 saltpeter stones, 4 powder stones, 2 brass boilers, a vessel for carrying water and a crate with bullets for handcannons, a pantry with a kitchen had: 19 boilers, two iron pans, 14 tin dishes, 12 tin plates, 17 spits, 3 mortars, 4 tin candlesticks. The cellar stored a barrel of old wine, two meads and four barrels of beer from Świdnica. There were 3 forged wagons, a light, horse-drawn carriage and 5 horses with harness in the yard. The Habsburgs seized movable goods to Vienna and gave the duchy in pledge.

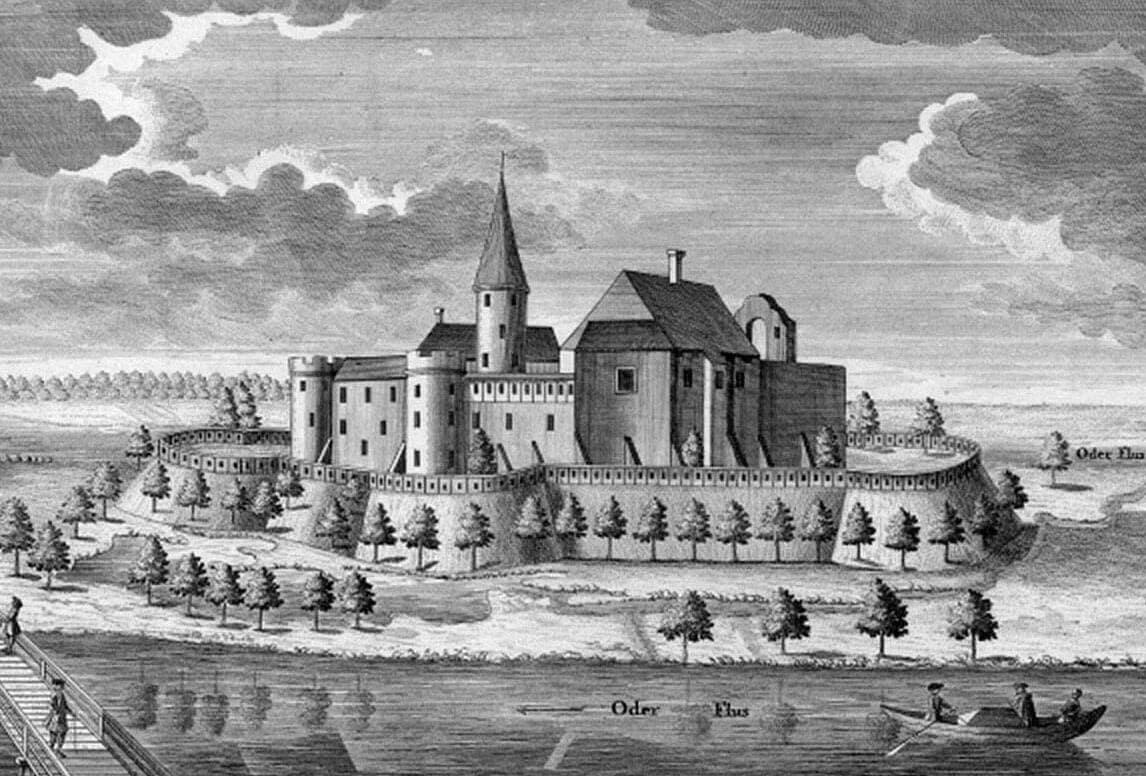

In 1552, the Duchy of Opole-Racibórz was granted to the duchess of Transylvania, Izabela, daughter of king Sigismund the Old. When she came to Opole she found the castle neglected and deprived of equipment. Only Jan Oppersdorf took up the renewal and expansion of the castle in 1557-1566. On his initiative eastern and southern wings were rebuilt. At the end of the 16th century, the castle was enriched with fortifications that made it an early modern fortress during the Thirty Years’ War. Unfortunately, in 1615 it was destroyed by a fire, although in 1633 and 1634 it managed to repulse the siege of imperial forces of general Goetz. Yet after the war, castle was dilapidated and neglected, so the bad condition did not allow the Polish king Kazimierz to live in it when he arrived in Silesia in 1655. With time, the buildings of the castle began to be demolish. First, in 1730 the burned western wing was removed, and in 1838-1855 the castle walls were pulled down and the moat was filled up. Earlier, in 1737 and 1739 additional damages were provided by further fires. In 1928-1931, by virtue of the decision of the German authorities, the rest of the castle was pulled down, keeping only a cylindrical tower thanks to the protests of the Polish minority.

Architecture

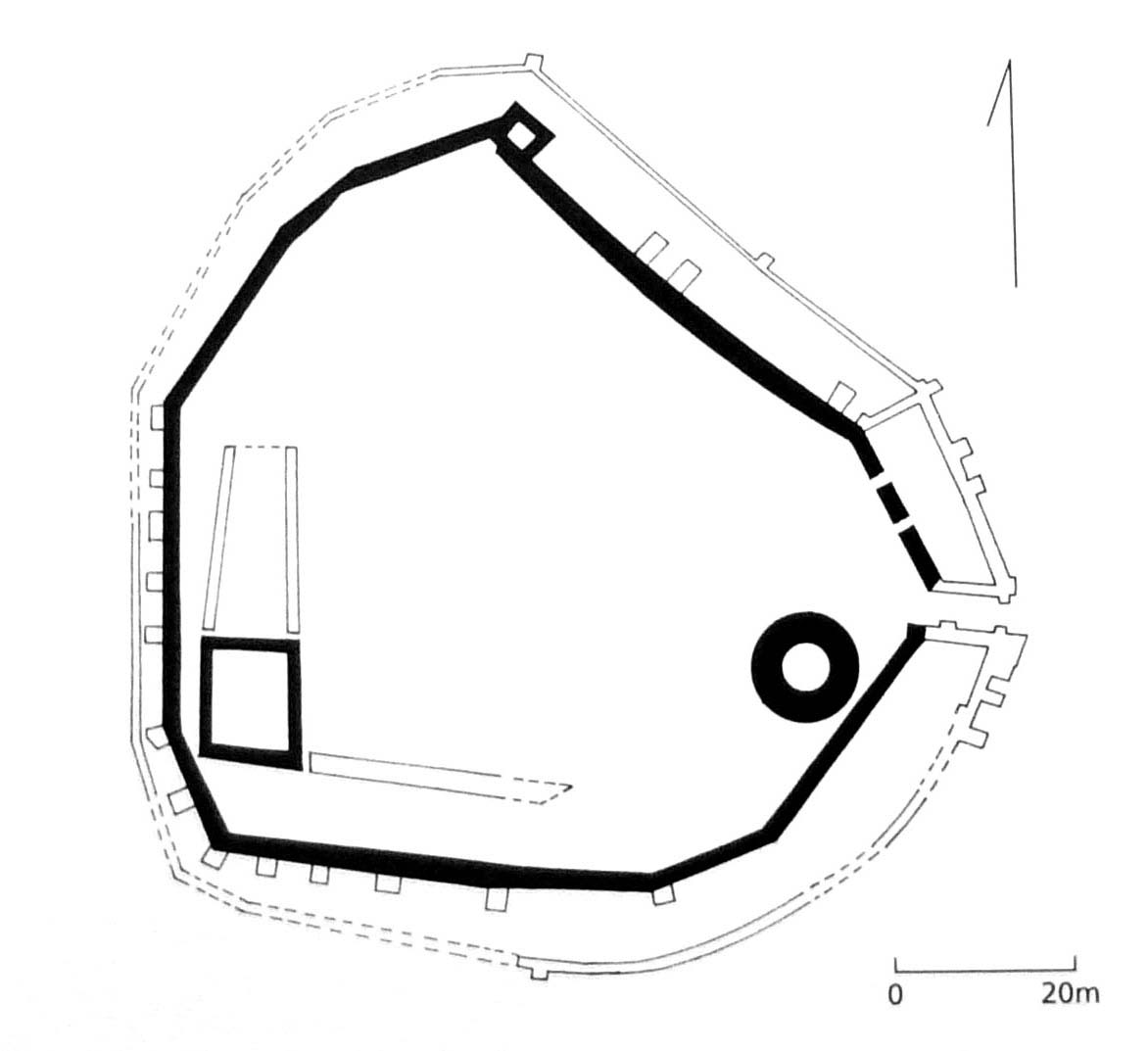

The Opole castle was built on the site of an early medieval stronghold, in the northern, swampy part of the island, in the area of Ostrówek, a headland of Pasieka Island washed by the waters of the Odra River. It consisted of a polygonal outline of massive defensive wall 2-3 meters thick, roughly repeating the course of the wood and earth ramparts of the stronghold, a small four-sided tower protruding in front of the perimeter of the walls in the north, and a four-sided, detached residential building measuring 12 x 15 meters, perhaps of a tower-like form. This keep was located in the south-west corner of the complex, i.e. on the opposite side of the gate, in theoretically the safest place in the courtyard.

The defensive wall of the castle was built as a full wall in sections that were particularly important for defensive reasons (e.g. near the entrance gate to the courtyard). On the northern and eastern sides, the curtains were made in the opus emplectum technique, so it had brick faces on the outside and inside, while the core was filled with limestone rubble and mortar. Moreover, stone was used in the plinth and in places in the higher parts. The top of the wall had a battlement, i.e. a breastwork behind which there was a wall-walk. Due to the considerable thickness of the wall, it was probably not widened with a wooden porch, but it could have been connected with a wooden footbridge to the floors of some buildings in the courtyard (e.g. a keep or a later bergfried tower). The defensive wall was built on the leveled ramparts of the stronghold, so it was exposed to subsidence and static problems, and as a result, from the 14th century it had to be supported with buttresses and re-faced in some sections.

In the 1280s, the castle was enlarged with a representative and residential building. Next to the older keep from the north, a two-story house was built, elongated in plan, located with its longer axis parallel to the neighboring curtain. In its upper storey there was a chapel dedicated to John the Evangelist, the apostles Peter and Paul and Mary Magdalene, and two or three chambers. The ground floor probably housed three rooms in a one line, layout typical of the Middle Ages (central vestibule and two side rooms). In the 14th century, the building was to be raised by a third floor. It was probably covered with a high gable roof, probably based on stepped gables (such gables of the oblong building were shown in a veduta from the first half of the 16th century). The second floor was to be accessible via an external spiral staircase.

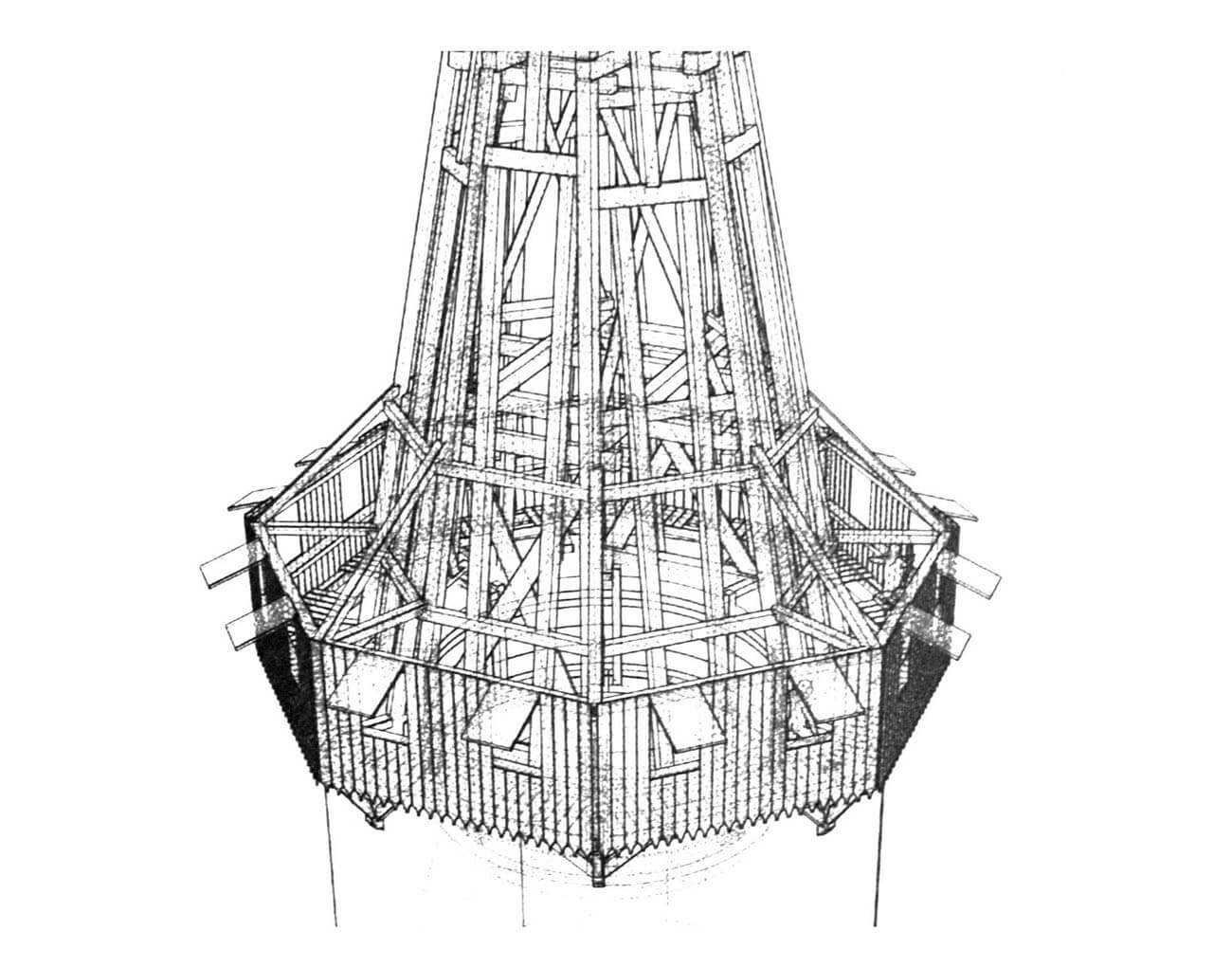

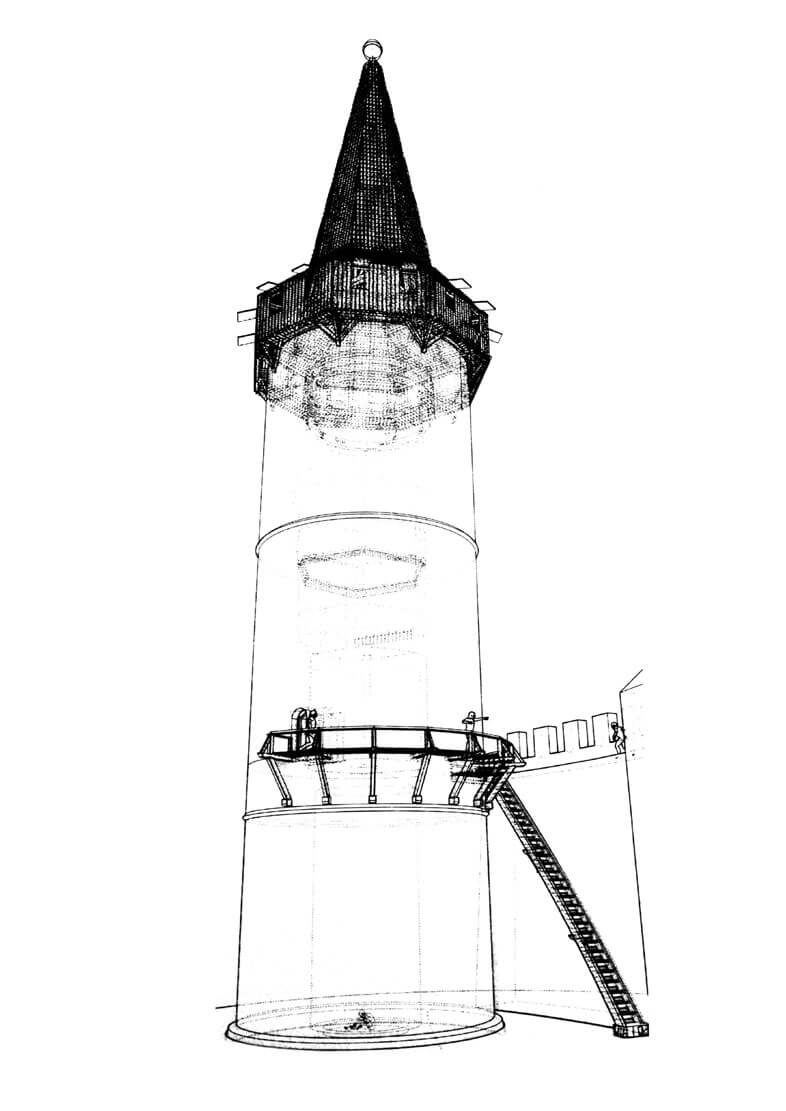

Around 1300, at the entrance gate, in the south-eastern part of the complex, a cylindrical tower was built, today known as the Piast’s Tower, which was a typical example of a bergfried, i.e. a tower of final defense. It was built of bricks and set on a 6-meter deep field-stone foundation. The thickness of its walls in the ground floor was over 3 meters, and the height was about 30 meters. It was not included in the perimeter of the defensive walls, but located in close proximity to them. Originally, the entrance to it was about 10 meters above the level of the courtyard, at the height of the first floor, and was accessible through a wooden gallery from the crown of the defensive wall. In case of danger, gallery could be easily dismantled, and the door to the bergfried itself was blocked with four bars set in openings in the wall (at the end of the Middle Ages, the original entrance was transformed into a window opening, and the new entrence was placed on the same level, but on the south-eastern side, so that it connected with a nearby building). Inside the tower, there was a round, high prison dungeon on the lowest storey, originally accessible only through an opening in the ceiling, and above a smaller, hexagonal room, perhaps a guardhouse, located at the entrance level. Both chambers were topped with brick barrel vaults, although the upper one was only from the end of the Middle Ages. Above, there were three more hexagonal floors, covered with wooden ceilings. To the second floor led a late gothic tunnel stairs created by fencing part of the room with a wall (originally only ladders were used to move). The top storey was used for active defense. It was probably originally topped with a high roof and a surrounding hoarding porch.

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, more buildings were added to the perimeter wall in the southern and western part of the courtyard. The area of the gate was also expanded, which in the times of Bolko II (1313-1356) was equipped with a gatehouse with a burgrave’s apartment on the first floor. The gatehouse protruded partially in front of the main defensive perimeter, and its outer corners were connected with the later outer wall of the zwinger. Next to the gate there were stables, supposedly able to accommodate as many as 80 horses, and in front of it, forming the eastern wing of the castle, the house of the duchesses, also known as the “Widow’s Court”. It is known that near the main tower there was a two-story kitchen and a bakery, in front of which there was a well, protected by a wooden casing.

Current state

Today, the only remnant of the castle of the Opole princes on Ostrówek is the cylindrical tower known as Piasts Tower, which is the city’s symbol. Currently, it is squeezed between the former registry building and the amphitheater. Despite the fact that here and there you can read that the pre-war office building is one of the most magnificent examples of modernist architecture, it actually disfigures the castle surroundings and has nothing to do with the historical appearance of the island. The tower itself, after a recent refurbishment, has been made available for sightseeing, which is presented in an interesting way, despite the lack of significant exhibits. Unfortunately, during the restaurant, the ahistorical crown of the tower was not changed.

bibliografia:

Kastek T., Krzywka M., Mruczek R., Wyniki badań archeologiczno – architektonicznych na terenie zamku piastowskiego na Ostrówku w Opolu w sezonach 2011-2012, “Opolski Informator Konserwatorski”, nr 11, Opole 2013.

Lasota C., Małachowicz M., Wyniki badań architektonicznych “Wieży Piastowskiej” w Opolu na Ostrówku, “Opolski Informator Konserwatorski”, nr 10, Opole 2012.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Popłonyk U., Opole, Warszawa 1970.

Siemko P., Zamki na Górnym Śląsku od ich powstania do końca wojny trzydziestoletniej, Katowice 2023.

Zajączkowska U., Zamek piastowski w Opolu, Opole 2001.