Historia

The Cistercian abbey in Oliwa was founded in 1186 by prince Sambor I of Gdańsk, although the first efforts regarding the foundation could have been carried out as early as 1178. Prince brought the monks from Kołbacz, and as the Kołbacz abbey was founded only a dozen years earlier, perhaps also from the mother monastery in Esrom in Denmark. The brothers were led by the first abbot of Oliwa, the Dane Dithardus, although in 1191 a new Danish monks arrived in Oliwa, perhaps because of some split or offense committed by the first monks, which did not appeal to the general chapter of Citeaux. The reasons for the ducal foundation could be devotional, but also important were the political results: honoring the reign of the Gdańsk princes, or establishing the resting place of the ruling dynasty, and economic, in the form of introducing and spreading new techniques in agriculture and crafts in Pomerania. Perhaps it also thought about acquiring missionaries to be sent to the still pagan Prussian territories in Pomesania.

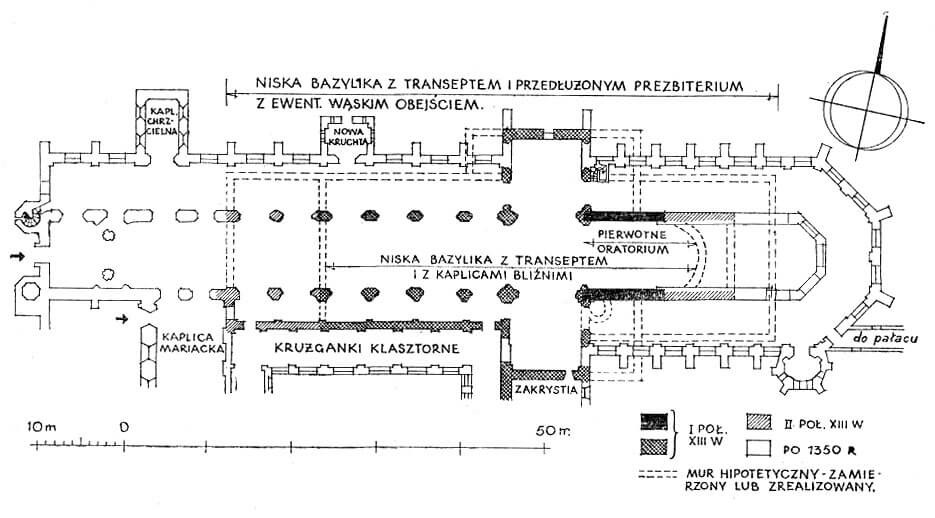

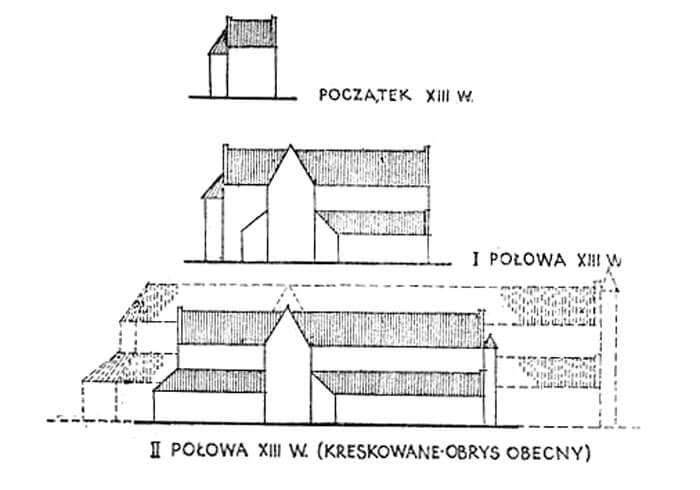

The original community had only twelve monks, therefore they only erected a Romanesque oratory and wooden residential buildings. It was not until the beginning of the 13th century that the oratory was adapted to the chancel, to which a transept and side chapels were added. First, the southern transept was erected, and after 1224 the northern one. After the invasion of the Prussians in 1236, the construction of the nave of the church began, as well as the first brick buildings of the monastery claustrum. Before 1243, the central nave was to be built up to the fourth bay, and then it was extended to the sixth bay, closed with a façade with a stair turret. These works were interrupted several times due to the invasions of the Prussians and the Teutonic Knights. In the second half of the 13th century, the eastern part of the church was rebuilt, the chancel was extended and the apse was removed, giving the church the shape that functioned until the Gothic reconstruction.

As early as in the 12th century, the monastery received several villages and valuable privileges enabling it to obtain income from fishing, along with the possibility of fishing at sea and on the shore within the borders of the Duchy of Gdańsk. More income came from the mills on the Strzyża River, as well as from the tithe from all taverns belonging to the Gdańsk stronghold, from the tithing from the duty, income from the Raciąż stronghold, or from the tithe of the princes’ cattle. The abbey was also released from all servant duties in favor of the prince, which gave monks greater rights over the subject population and was released from war obligations, with the exception of the reconstruction of the stronghold and the coast in Gdańsk. The further growth of monastic estates took place in the 13th century thanks to the grants of the nobility and rulers. Their first general charter confirmation was issued in 1224 by prince Świętopełk. While at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries the abbey had 17 villages, in 1245 it already had 35 settlements, and in 1283 the monks owned land in 42 villages.

The monastery was looted and burned down by the pagan Prussians for the first time in 1226, in retaliation for the invasions of Polish princes in 1222 and 1223. The monks, together with Abbot Etheler, were to be kidnapped and soon killed at the gates of Gdańsk. New monks soon arrived from Kołbacz and began to rebuild abbey, but in 1236 the Prussians invaded Oliwa again, this time in retaliation for the armed expedition provoked by Pope Gregory IX, who called for a crusade against the Baltic pagans. Unable to occupy Gdańsk, the Prussians destroyed the Cistercian monastery and tortured 6 lay brothers and 34 villagers. The abbey also experienced several Christian crusades led by the Teutonic Knights, conducting an invasive policy towards Gdańsk Pomerania and interfering in the territorial disputes of prince Świętopełk with brothers Sambor and Racibor. When in 1243 the anti-Teutonic uprising of already Christian Prussians broke out, the order accused Świętopełk of inciting and supporting them, and in 1246 invaded the vicinity of Gdańsk and burned down the abbey and its farms. The next devastating invasions took place in 1247 and 1252, while Świętopełk was supposed to shelter and defend himself in the monastery during the latter.

In the second half of the thirteenth century, the invasions on Oliwa ceased, but in 1276 prince Sambor, favoring the Teutonic Knights, handed over them the Gniew land taken from the Cistercians. This conquest was of great strategic importance for the Teutonic Order, as it crossed the land and water route connecting the Polish lands with the sea. The Cistercians tried to assert their rights at conventions and during negotiations, but to no avail. Ultimately, in 1283, they had to cut themselves off from the Gniew region in exchange for compensation for 16 villages obtained from prince Mściwoj II. The abbey of Oliwa also had a long-lasting dispute with Michał, the bishop of Kuyavia. It concerned the tithing of monastic goods, and the abbey was even excommunicated during it. Ultimately, the agreement was reached in 1249 thanks to the prince Świętopełek. The bishop resigned from the tithes of Oliwa in exchange for two villages, thanks to which the archbishopric of Gniezno retained its influence in Pomerania. After the Gdańsk massacre in 1308, Oliwa, along with the entire Pomerania, fell under the rule of the Teutonic Knights. The then abbot Rüdiger was to buried in Oliwa at the church of St. James Pomeranian knights killed during the fights, which was probably caused, among other things, by the monks maintaining close relations with Polish king Władysław Łokietek. Property and territorial disputes between the Cistercian monastery and the Teutonic Knights lasted long. They only expired in 1342, when the Grand Master Ludolf König von Wattzau recognized all the Cistercian claims.

At the beginning of the 14th century, the Oliwa Abbey became a powerful economic force with about 58 villages. Although the number of donations decreased then, the salary of the abbey was increased by purchasing land from petty chivalry. The good economic situation was interrupted by misfortunes. In 1350, due to inept cleaning of the kitchen chimney, the fire consumed the abbey completely. Only the walls of the church, the dormitory and the refectory were to survive. The church was rebuilt in the Gothic style, thanks to new grants and the support of the Teutonic Knights. At the same time, the nave was extended by four bays, the chancel was also extended and the ambulatory connected with the chapel of Holy Cross. At that time, a great refectory and a lavatory were built in the monastery. These works lasted almost throughout the second half of the 14th century.

The beginning of the 15th century was not successful for the monastery: high taxes imposed by the Teutonic Knights, epidemics and wars. The Oliwa Cistercians had to send people, carts, sleighs and horses to the Teutonic armed expeditions. The Teutonic Knights, ruined after the defeat of Grunwald, needed money to pay the mercenaries’ wages and purchase weapons, so they imposed new taxes, also on the clergy. The constant marches of troops, spoilage of the coin, the collapse of trade and high prices brought about great economic damage, and the situation was worsened by the epidemics of 1416 and 1427. Soon after, in 1433, Pomerania was invaded by Czech Hussites, allied with Poles. The then abbot of Oliwa, Bernard, had to take refuge with the monks in Gdańsk, where he lived in his own granary.

When the Thirteen Years’ War broke out in 1454, the abbey supported the Prussian Union and the Polish king in the war with the Teutonic Order. The reasons for this were probably economic, the desire to benefit from the revival of trade with Poland and numerous political freedoms, which is why during the protracted fights the abbey often granted loans to pay for the allied mercenary troops. In 1460, after the Teutonic Knights had captured Lębork, Puck and Bytów, Polish troops of Gotard from Radlin and Wawrzyniec Schrank fortified the abbey, staying there until next year and taking part in the fights that devastated the monastery lands. Eventually, after 1466, as a result of the Toruń Peace, Oliwa and all Gdańsk Pomerania passed into Polish hands as Royal Prussia.

The abbey’s relations with Polish rulers were vivid in the second half of the 15th century. In 1467, Kazimierz Jagiellończyk, at the request of Abbot Paweł, approved all the possessions, privileges and rights received from Pomeranian dukes, kings and Teutonic Knights, and his successor, King Alexander, also came to Oliwa. In 1512, Sigismund I the Old, at the request of the abbot and the all monks, renewed and at the same time confirmed the agreement of the Oliwa monastery with the Norbertine nuns from Żuków regarding the property in Kępa Oksywska, about which the abbey had been arguing with the sisters for many years. In addition, organizational changes took place at the beginning of the 16th century. From 1508, the abbey of Oliwa had the right to be visited by the abbot of Pelplin, due to the loosening of older filial connections from the end of the 15th century and the transition of Oliwa and Pelplin abbeys to the Baltic Cistercian province.

In the years 1519-1521, during the ongoing Polish-Teutonic war, mercenary German troops rushing to help the great master Albrecht were repulsed near Gdańsk and, according to the records, during the retreat, they passed through Oliwa. Undoubtedly, this must have led to the devastation of monastic property. In 1561, the monastery helped king Sigismund August during the Livonian War and guaranteed the loan of Gdańsk for the king, which was never repaid. For this reason, the Gdańsk demanded money from the guarantors, but the Warsaw Sejm of 1573 and the abbot of Oliwa, Kasper Geschkau, opposed it. In 1577, during the dispute between Gdańsk and King Stefan Batory, the same abbot took the side of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. This led to the attack of Gdańsk Protestants on the monastery and severe damages, especially in terms of the furnishings of the abbey church. A year later, Gdańsk finally recognized Batory’s authority and was forced to pay 20,000 guilders in compensation. Thanks to this and the generous grants of the king and Polish magnates, the monastery was rebuilt roughly in its former shape and style, and thanks to the good relations of the monks with Polish rulers, they took care of the abbey during the spreading Reformation, rejecting the demands of the Pomeranian nobility wanting to drive the brothers out of Oliwa.

Kasper Geschkau raised the Oliwa monastery from economic ruin and survived the period of the onslaught of Protestantism, but the internal life in the abbey did not improve. In 1569, the number of monks was only about 12, and after the death of Kasper, the chronicler of Oliwa, Adler, described the relations there as catastrophic. Discipline in the monastery fell to such an extent that no masses were celebrated, monks escaped from the enclosure, and the goods of the order were squandered. It was only when Hieronim Rozrażewski took over the rule over the diocese of Włocławek in 1581 that the religious life improved. Under the Geschkau Abbot, the construction of new vaults over the nave and transept was completed in 1582. In the times of Abbot Dawid Konarski at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, the monastery was surrounded by defensive walls, the church’s interior was changed to Renaissance and the library collections were enriched.

In 1626, the monastery was plundered by the Swedish army during the war with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, although the brothers survived the hard times by escaping to safe Gdańsk. Due to the fact that the abbey church had lost a large part of its furnishings, subsequent abbots founded a new, this time baroque interior of the temple. In 1636, the abbey was visited by King Władysław IV, the papal nuncio Honorius Visconti and a French envoy, and in the rebuilt abbey, after the destruction of the Swedish Deluge, a Swedish-Polish peace treaty was signed in 1660.

In the 18th century, despite the requisition from the Northern War period and the devastation caused by the plague of 1709, the abbey avoided major damages. The activity of the monastery ended in 1772, with the first partition of Poland, when Oliwa came under Prussian rule. In 1820, the authorities prohibited the admission of novices, and in 1831 liquidated the abbey. Its goods were divided between the city of Gdańsk and the Prussian king. The novitiate, priorat and infirmary were demolished, and some of the buildings were adapted to the needs of the parish. The Cistercians returned to Oliwa right after the Second World War, but they did not regain the abbey in which the parish operated.

Architektura

The Oliwa abbey was founded at the foot of a hill, in a muddy valley stretching all the way to the sea coast, about 3 km away. A small stream flowed through this valley towards the Bay of Gdańsk, the clean water of which was crucial for the daily functioning of the abbey.

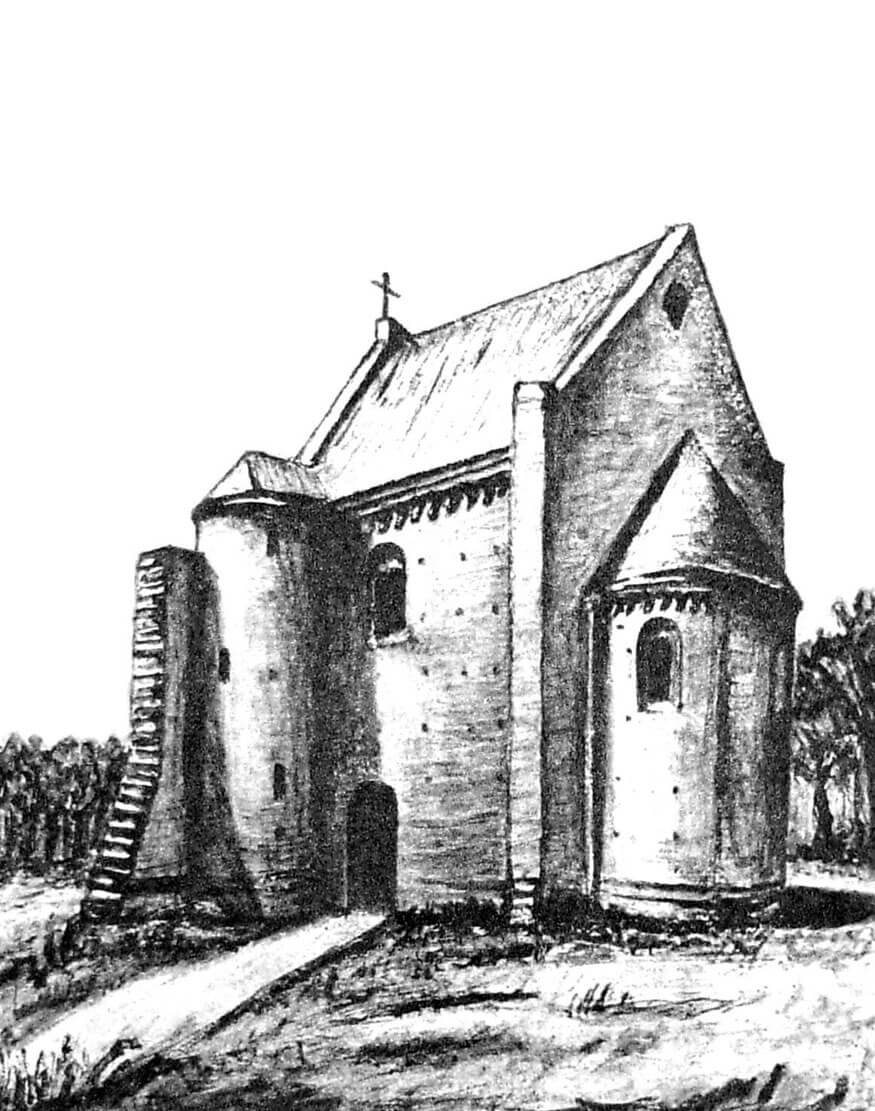

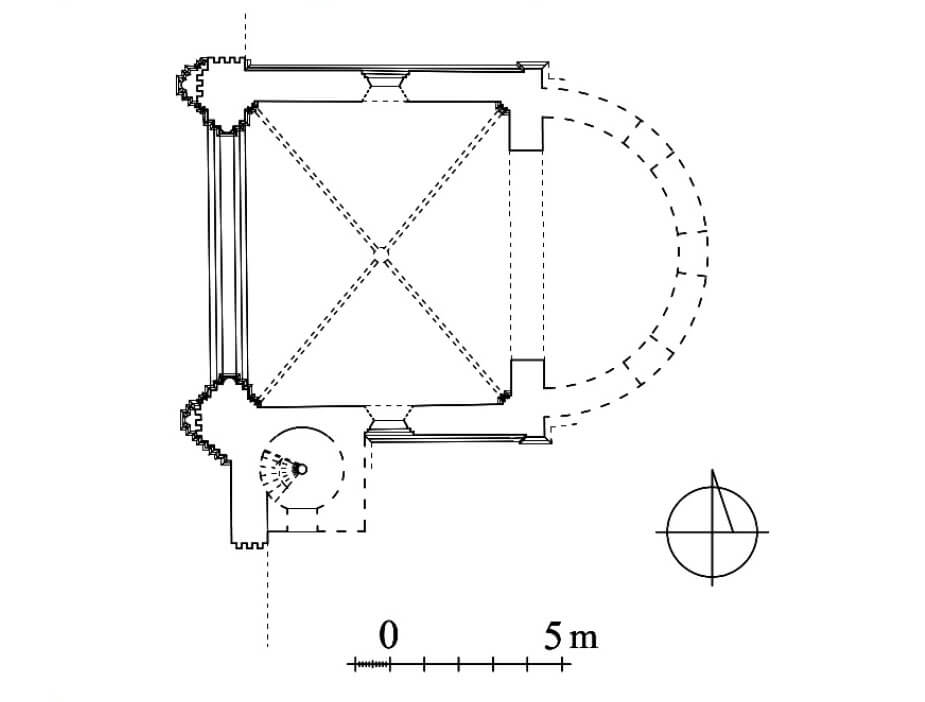

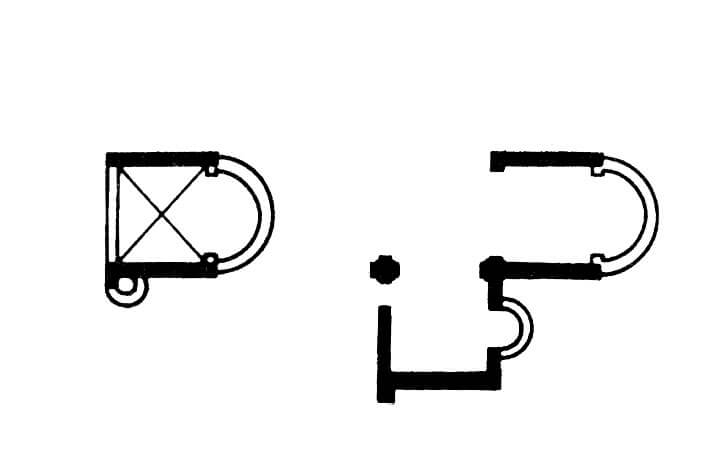

The oldest brick building in the abbey was a small church – oratory from the fourth quarter of the 12th century. It was a brick building on a stone foundation, a single nave, probably closed on the eastern side with a semicircular apse. A round turret with stairs leading to the attic was adjacent to its from south-west. The corners of the oratory were covered with pilaster strips, and the whole was crowned with an under-eaves frieze made of double semicircular arcades. The interior, topped with a cross vault, was illuminated by two semicircular windows with diagonal jambs flanked by shafts.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the construction of the southern arm of the transept began, while the older oratory in the planned new, larger church took over the role of the chancel. The started transept was added to the south-west corner of the oratory, and its walls were 3 meters higher. They were topped, as in the older building, with a frieze made of double, semicircular arcades. In addition, the southern gable was filled with a decorative opus spicatum bond, with vertical shafts passing into semicircular arcades on the consoles. The corners of the transept were covered with pilaster strips, and the interior was illuminated by windows about 2.5 meters wide, probably two-light. With an arcade on the axis of the eastern wall, the interior of the southern arm of the transept opened onto the apse. The builders planned to put on the vaults, but they did not implement it. The raise of the transept resulted in the reconstruction of the oratory. The vault and the stair turret colliding with the new walls were removed and the walls were also raised to a new height. The old windows were also bricked up, new windows were pierced out much higher, so that they crossed the original under-eaves frieze. They were probably given the form of two-light biforas.

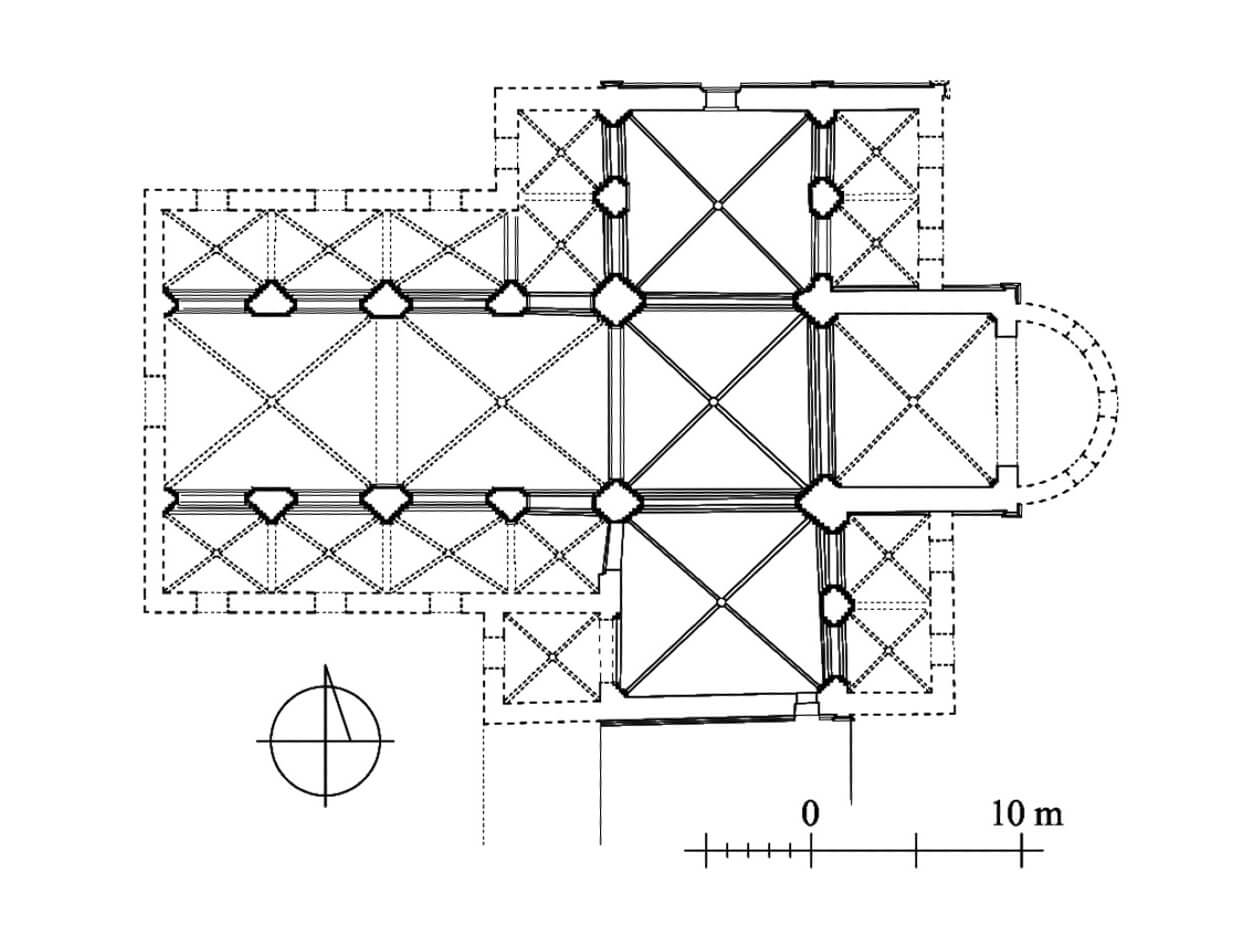

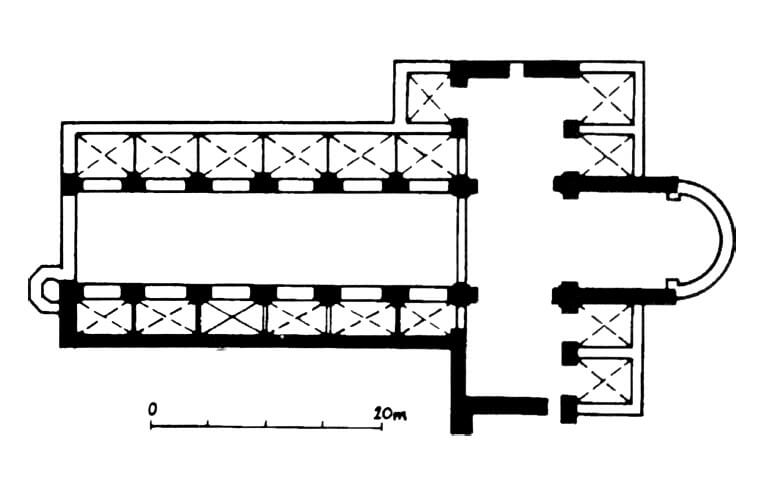

The third phase of the construction of the monastery church, as a result of which it received the form of a typically Cistercian temple, took place in the second quarter of the 13th century. At first, the construction was continued at the northern transept, but with the change of architectural detail, different decorations and a different format of bricks. On the eastern side of the northern transept there are two, twin, rectangular chapels, connected in the interior with the transept by ogival arcades. The same shape was given to the southern arm, where the apse was removed and the arcades were pierced to two single-bay chapels, although the northern part of the transept additionally received a pair of chapels also on the west side.

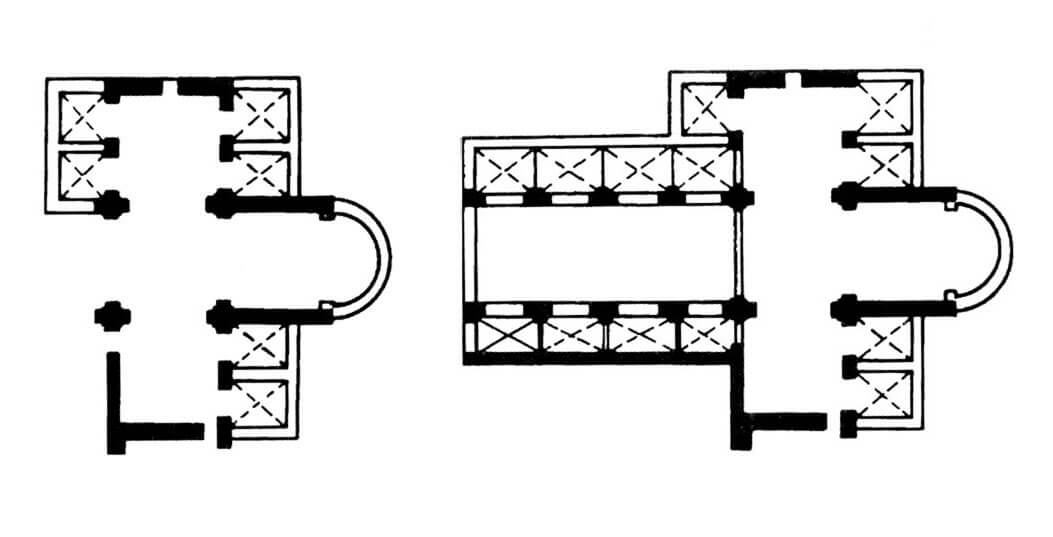

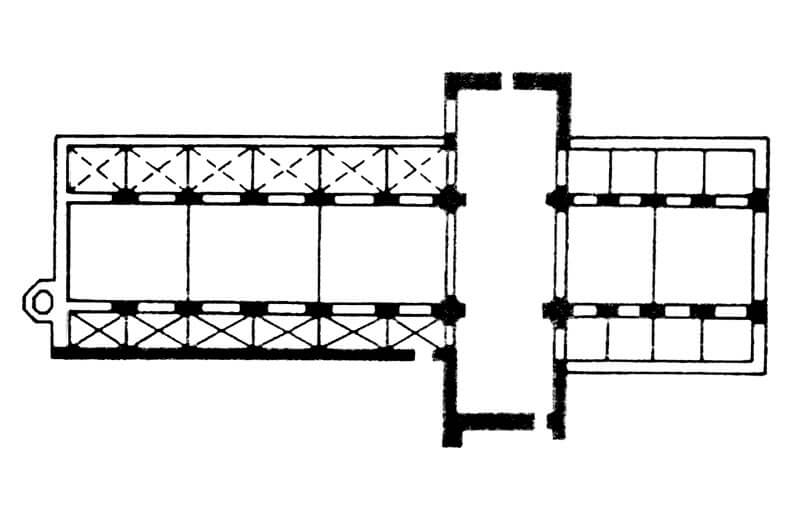

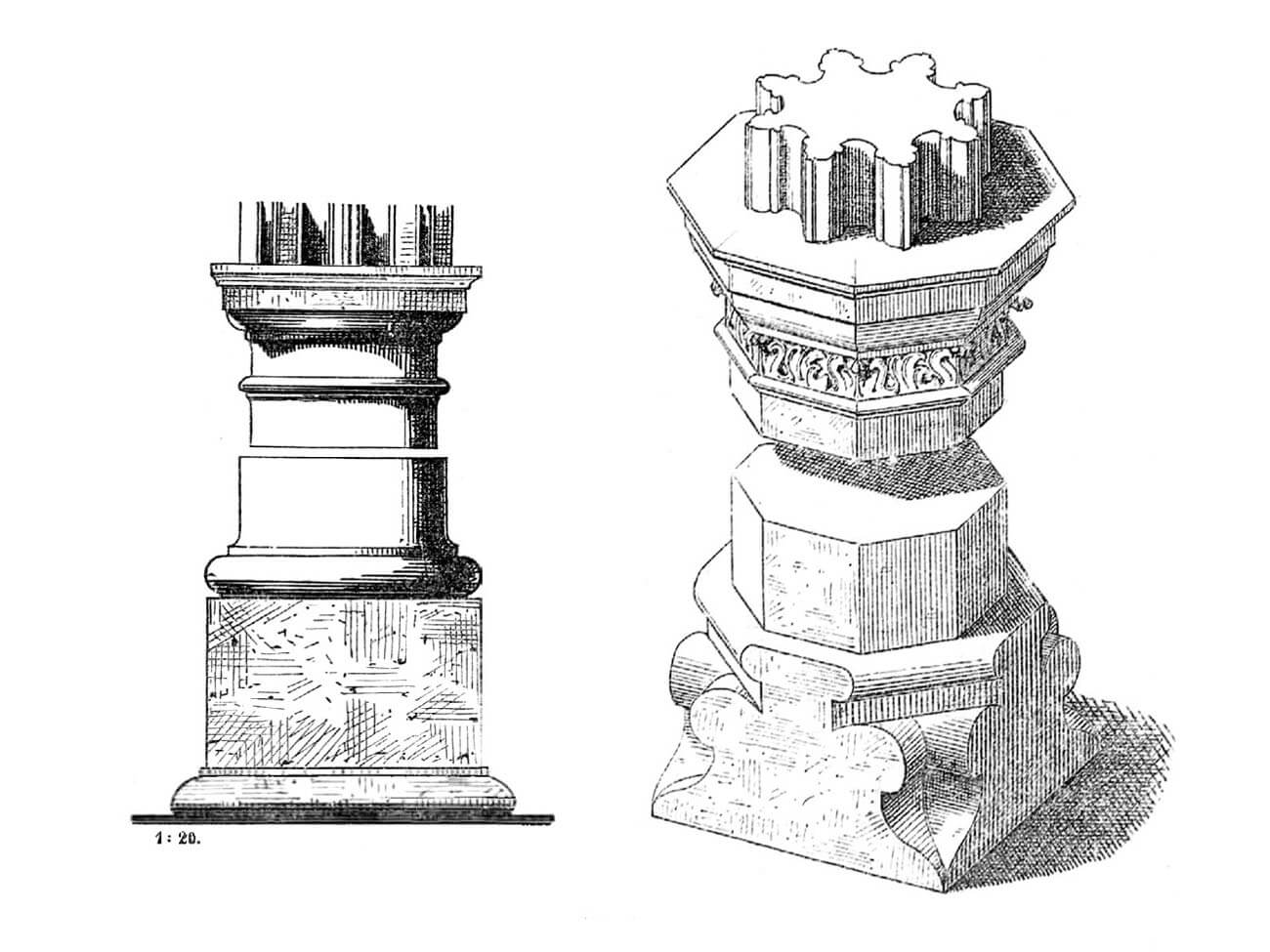

After a short break in the works, most likely caused by another attack by the Prussians in 1236, the construction of the nave in the form of a three-aisle basilica was erected in a tied system (each bay of the central nave was twice larger than bay of the aisle). On the external façades, there were lesene – buttresses with pilasters inside, and on the axis of each bay there was a two-light window, framed by a shaft moulding. Inside, the walls of the central nave were supported by fragmented pillars and pierced with pointed arcades, the arches of which flowed down into half-columns with trapezoidal capitals. The rhythm of the arcades marked the division into bays in the aisles, topped with cross vaults. One of the numerous invasions on the abbey, this time perhaps of the Teutonic Order, caused a short break in the work on the nave, after which a new-shaped window was inserted in the northern wall – large and one-light. In order to maintain the integrity of the nave, the previous two-light windows were rebuilt, and the whole of the six-bay nave was closed from the west with a facade flanked from the south with a staircase turret. At that time, the church had the shape of a Latin cross, consisting of a three-aisle nave, a transept with eastern chapels and a chancel (the so-called Bernardine plan), with only the side aisles covered with vaults. As Cistercian churches were inaccessible to the faithful at that time, large pilgrimage processions did not yet take place there, so they did not need large chancel. Large naves and transepts with side chapels were to house numerous side altars, of which there was to be as many as monks, so that each of them could celebrate a private liturgy. A feature of the early Cistercian churches was also simplicity and the lack of great decorativeness, manifested, inter alia, in the towerless facades. In Oliwa, an additional characteristic feature were large planes of the walls, devoid of architectural detail and horizontal divisions, and striking with the monumental appearance of the walls, rhythmicized with arcades and flat pilaster strips.

The fourth stage of the expansion of the abbey church from the second half of the 13th century led to significant changes in its appearance. At that time, the apse at the chancel (the former, elevated oratory from the 12th century) was demolished and placed one bay to the east. The twin chapels at the transept were also demolished, and in their place two early Gothic side aisles were erected, opened with four ogival arcades onto the central nave of the choir. Their eastern closure is not certain, it was probably rectangular or the central nave of the chancel ended in a semicircle, there could also be shallow altar recesses in the walls. When the Bernardine plan was abandoned, however, church was not only limited to the horizontal extension of the eastern part, but the walls of the chancel and transept were raised. These changes were related primarily to the improvement of the economic situation of the abbey and the rapidly growing number of monks, who had to fit into the church and for whom side altars had to be placed.

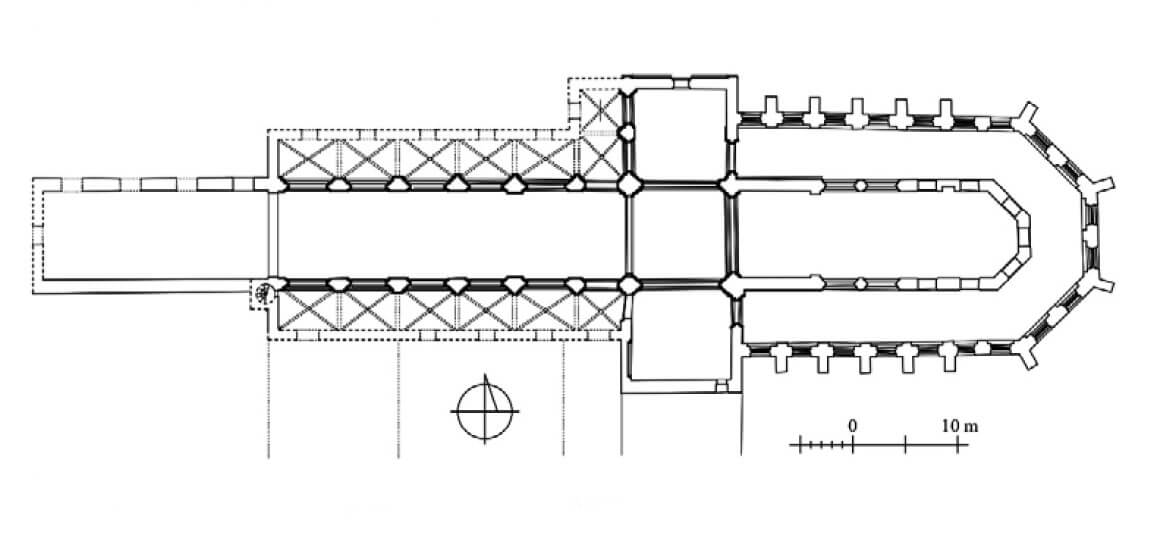

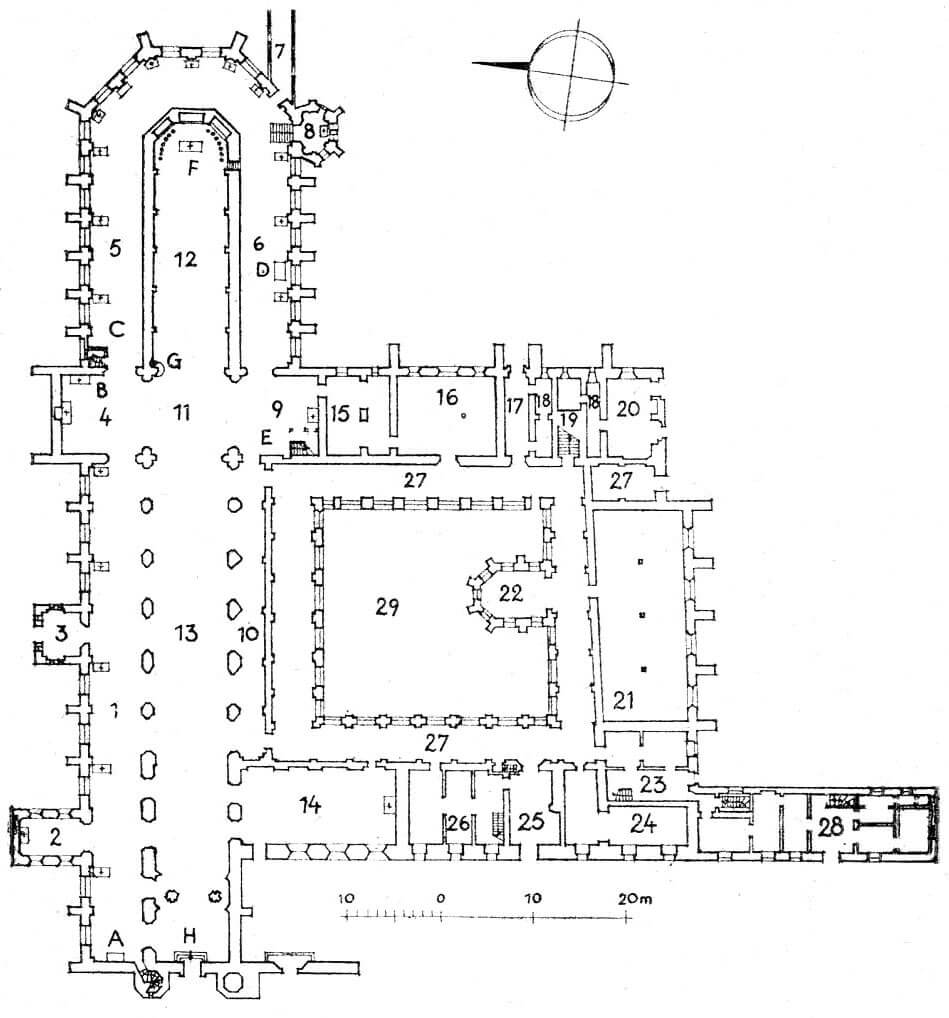

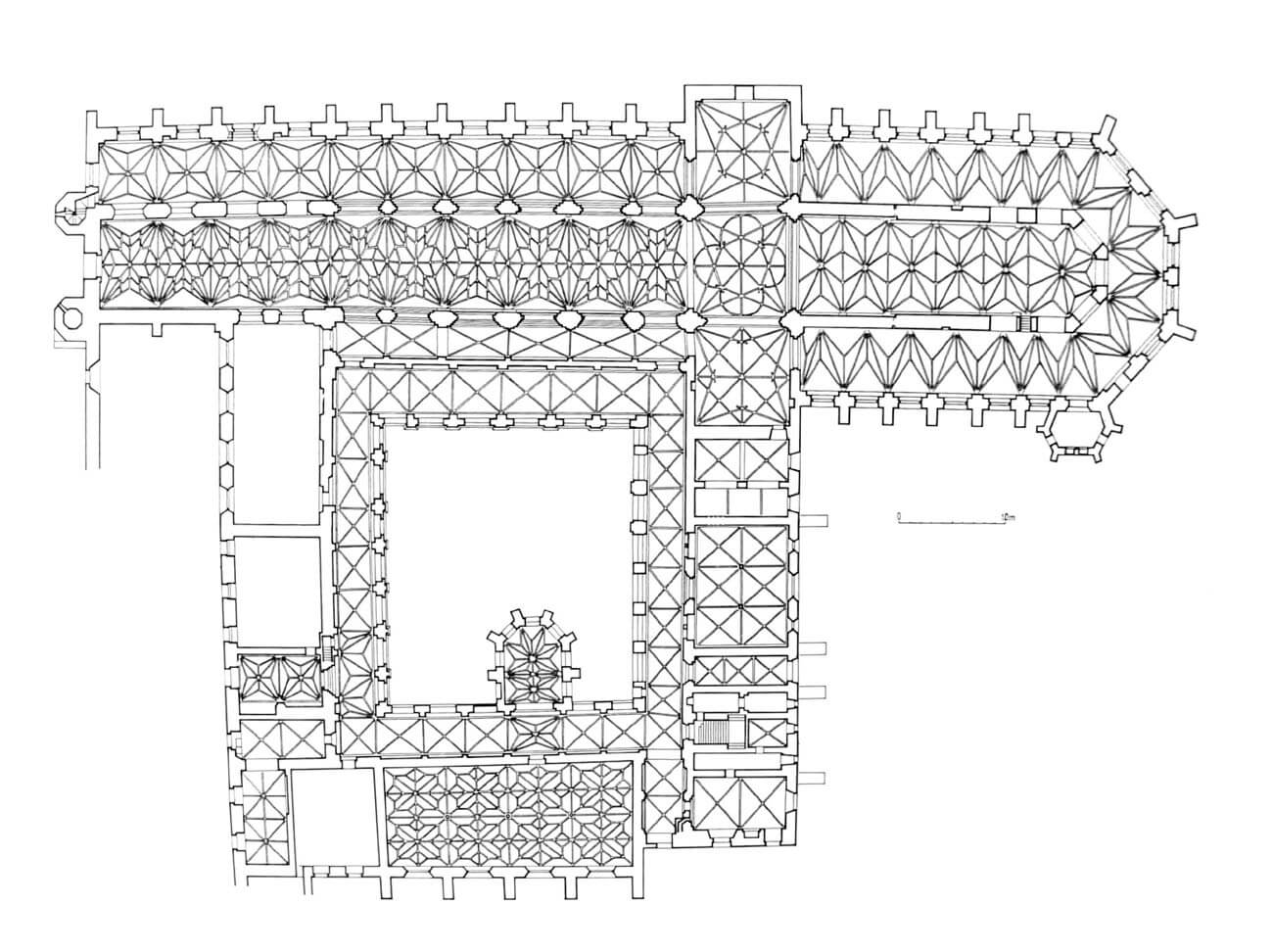

The reconstruction of the monastery after the destruction in 1350 shaped its basic Gothic look. First, the nave on the west side was extended with an elongated four-bay chapel, which was then transformed into the central nave with a side aisle added from the north (the old northern aisle was demolished to adapt the Gothic aisle to the extended nave). In addition, the rectangular chancel was extended by two bays to the east and, in accordance with new trends, it was ended polygonally. The nave was also raised to the height of the eastern part of the church. The church was then in the form of a ten-bay basilica with central nave, two aisles, a transept and a three-aisle, polygonal chancel with an ambulatory, with a total external length of as much as 107 meters (one of the longest Gothic churches in Poland). The western façade was diversified with two slender towers, 46 meters high, the northern aisle was widened, and a polygonal chapel of Holy Cross was built at the southern wall of the ambulatory. The northern aisle, the ambulatory and the chapel of Holy Cross were reinforced with buttresses.

Inside, in the chancel, a stellar-net vault with a guiding rib was installed, lowered on head-shaped corbels, in the northern aisle a four-arm stellar vault based on tracery and mask corbels (one with the image of a hybrid), in the ambulatory three-supported vault from the second half of the 14th century or the beginning of the 15th century. In the southern aisle, an older cross-rib vault from the 13th century was left. The central nave was covered with a net-stellar vault with inscribed an eight-pointed star. It was supported on pilaster strips, which were lowered to the floor between the second and third as well as the sixth and seventh bays, and overhanged in the remaining bays. A stellar vault with interwoven ribs was used in the transept.

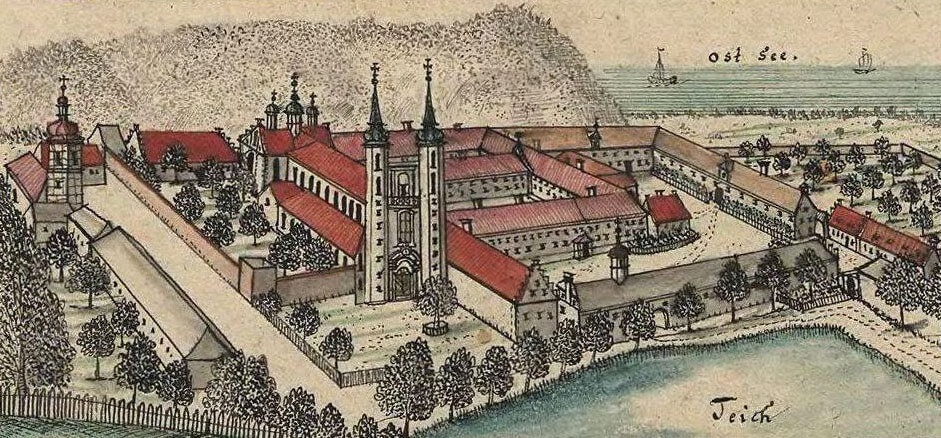

The complex of monastery buildings was erected on the south side of the church, on a quadrilateral plan with an internal square patio, surrounded by cloisters connecting the ground floor rooms. In the oldest and most important east wing, on the ground floor, there was a two-part sacristy, and on its southern side, the chapter house, i.e. the place of daily meetings of the brothers under the leadership of the abbot, where the daily matters of the abbey were discussed, and the vicious monks were deliberated and judged. It received the form of a two-aisle, three-bay room, covered with a cross vault supported by two columns. Further south there was a passage to the cemetery and gardens at the back of the abbey, and a prison located next to it, located just behind the stairs leading to the second floor. The last room of the east wing was the fraternity in which the monks performed manual works, especially in the winter time. The first floor was filled with the monks’ dormitory, connected to the transept of the church on one side and latrines on the opposite.

There was a Great Refectory in the south wing. Its interior received two aisles, four bays in length, covered with a stellar vault supported by three columns and corbels decorated with the coats of arms of church and state officials from the end of the 16th century. From the west, the refectory was adjacent to the kitchen, while from the north, in front of the entrance from the cloisters, in the courtyard of the patio, there was a polygonal closed lavatory in which monks could wash before meals.

The west wing originally housed lay brothers’ rooms with their separate refectory (a Small Refectory, also called the “Hall of Peace”), a kitchen and a dormitory. The Small Refectory was covered with a cross-rib vault and an eight-field vault. In the west wing there was also St. Mary’s Chapel, first recorded in 1577. There was probably also a gate providing communication with the area in front of the monastery claustrum.

Current state

The church and abbey in Oliwa, preserved to this day, is a testimony to many architectural changes, both medieval and early modern. The lower part of the walls of the two western bays of the chancel are the side walls of a small oratory from the 12th century, while the transept and the four eastern bays of the nave (without the northern aisle) with the raised chancel survived from the first half of the 13th century. The fifth and sixth bays of the nave, counting from the east, come from the second half of the 13th century, while from the time of the Gothic expansion after 1350 are the four western bays of the nave with western towers, the entire outer wall of the northern aisle and the ambulatory with the southern chapel of Holy Cross, with the western facade significantly transformed in the early modern period. The vaults of the northern aisle, chancel and ambulatory with decorative ceramic supports are also Gothic. The vaults of the nave and transept with painted corbels in the form of shields were founded in 1582. The claustrum buildings basically have the form obtained after the reconstruction at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, but it come from the 13th century (east wing) and the 14th century (southern and western wings). At the monastery complex there is a 14th-century granary, and the eastern part of the abbot’s palace dates back to the 15th century, although it lost its medieval stylistic features.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Dąbrowski K., Opactwo cystersów w Oliwie od XII do XVI wieku, Gdańsk 1975.

Die Bau- und Kunstdenkmäler der Provinz Westpreußen, der Landkreis Danzig, Danzig 1885.

Wetesko L., Romańska i wczesnogotycka architektura kościoła pocysterskiego w Oliwie (XII-XIII w.), „Nasza Przeszłość” nr 83, 1994.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.

Wyrwa A.M., Opactwa cysterskie na Pomorzu, Warszawa 1999.