History

The first record of Muszyna appeared in documents in 1288, when it passed into the hands of the bishops of Kraków, after their dispute with the heirs of Wysz from Niegowić was settled. At the beginning of the 14th century, the estate in Muszyna was in the hands of the Bishop of Kraków, Jan Muskata. It was probably then that a wooden and earth stronghold was built, about 100 meters to the north from the later castle. However, already around 1304 – 1308, Muskata lost its property as a result of the confiscation of Władysław Łokietek, due to fights with the ruler during the period of his unification of the fragmented Polish lands. In 1391, during the reign of Władysław Jagiełło, property was recovered for the bishopric of Cracow by bishop Jan of Radlica. In this grant the “castrum Musszina” was recorded.

The stone castle was built at the end of the 14th century or early 15th century. Although work cannot be ruled out on the initiative of Bishop Jan of Radlica, it is definitely more likely that the founder of the castle was Zbigniew Oleśnicki, holding the office of bishop in the years 1423 – 1455, known for his investing and construction activities. He also reorganized the Muszyna estates and established the offices of burgrave and starost of Muszyna. In such a case, the raid of Muszyna by Stibor of Stiboricz in 1410, commanding the troops of the Hungarian King Sigismund of Luxembourg, would still affect the old, timber castle, not a stone building. The then commander of the castle garrison, a certain Mikołaj Gładysz from Łosie, was supposed to surrender Muszyna due to its too weak castle crew.

The Muszyna castle in its original shape did not last long. Errors at the initial stage of construction, especially in the construction of foundations, as well as the low quality of masonry work led in 1455 to a major construction disaster certified by written sources. Certainly the gate and the north curtain wall adjacent to it from the east and west were destroyed. Such great damages, which the staroste of Muszyna, Jan Wielopolski estimated for a quarter of the castle, could not be repaired in a short time and with the means at his disposal. Therefore, the decision was made to make only temporary repairs at the defect locations using half-timbered structures.

The weakened fortifications of the castle certainly contributed to its fall in 1474, when the border land was devastated by the Hungarian invasion led by Thomas Tarczay. Undoubtedly, the battle that took place at that time was short, but extremely intense, as evidenced by the considerable number of military items found and numerous signs of burning from that period. In the same year, as a result of the agreement with Stara Wieś, Matthias Corvinus agreed to release the prisoners, return the stolen canons, return the castle and help in its reconstruction. The first major repair works were most probably undertaken only in 1488, but the castle regained its full splendor only at the beginning of the 16th century. The large-scale reconstruction probably absorbed significant funds and introduced many changes to the appearance of the building, referring to a higher standard of living (the stone window frames ordered in Bardejov in 1508 were to refer to the local town hall).

At the end of the 16th or at the beginning of the 17th century, the castle burnt down again. After this disaster, no residential buildings were rebuilt, and the function of the castle was limited to the role of a watchtower. It is known that on the castle were two-man guards, which were to grow five times in days of danger. The deteriorated stronghold was also prepared for defense during the Swedish invasion in 1655, gathering timber beams and boulders. Later documents fall silent about the castle. It probably played the role of the fortified seat of the bishop’s starosts and border stronghold until the middle of the 18th century, when it was abandoned and fell into disrepair. When Muszyna was captured by Austrian troops in 1770, the castle was no longer suitable for use.

Architecture

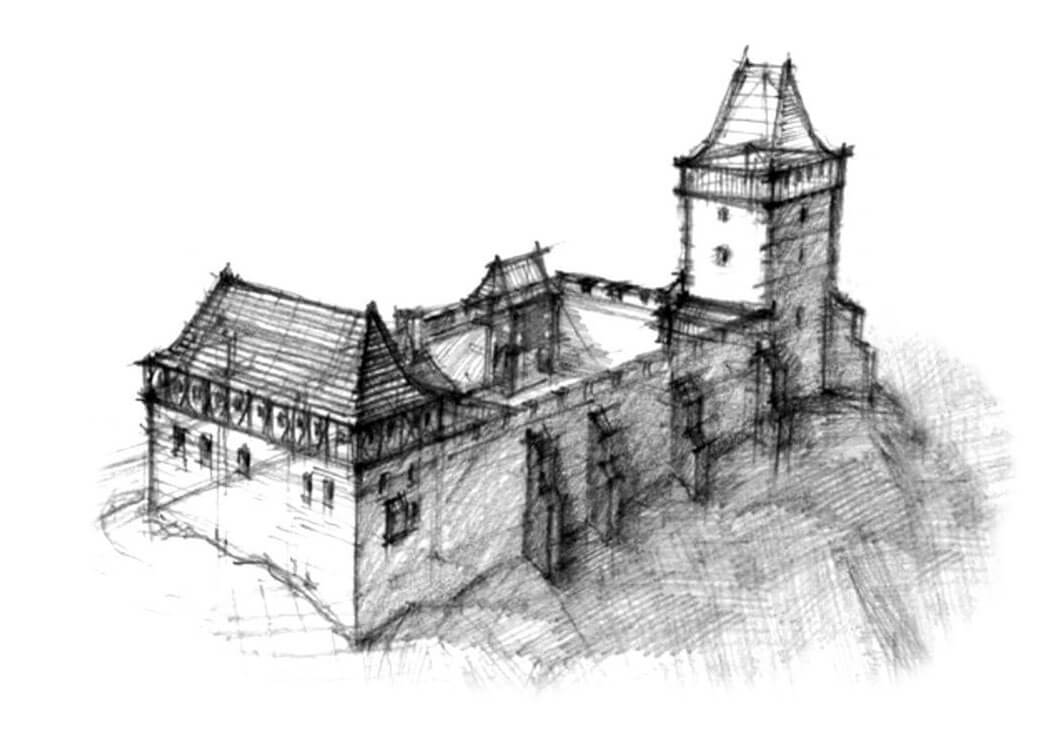

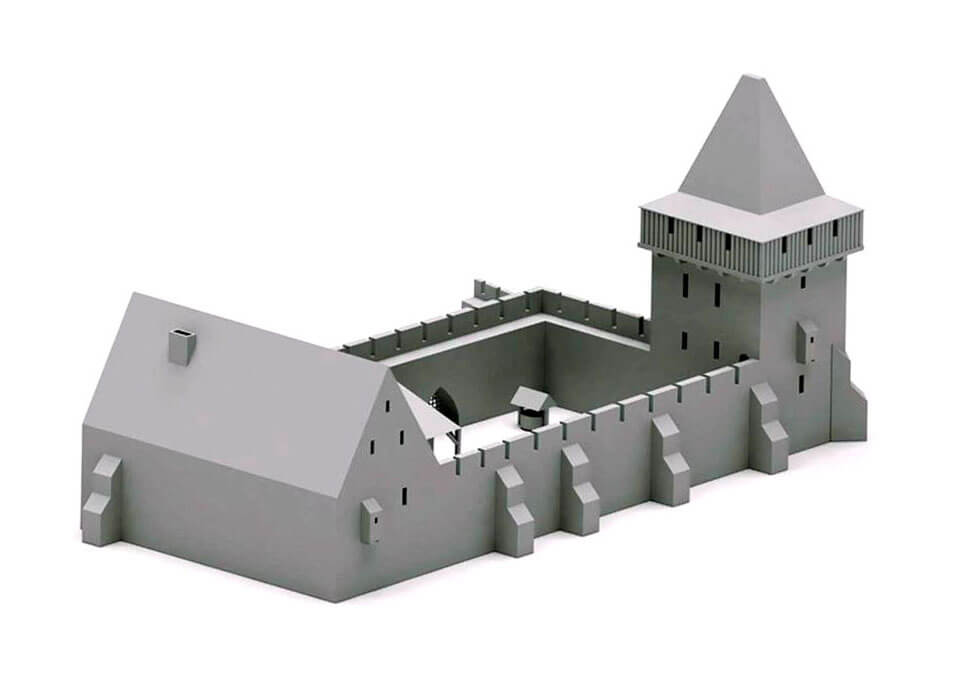

The castle was situated on the top of a high hill, at the end of a promontory towering over the bend of the Poprad River in the south. It had excellent natural defensive conditions because the slopes of the hill dropped steeply from three sides, leaving the only convenient access from the north, from the rest of the mountain range, where there was a natural depression in the ground, which, after deepening, acted as a ditch. Additionally, from the east and west at the foot of the castle promontory, the Muszynka and Złocki Potok rivers flowed into Poprad.

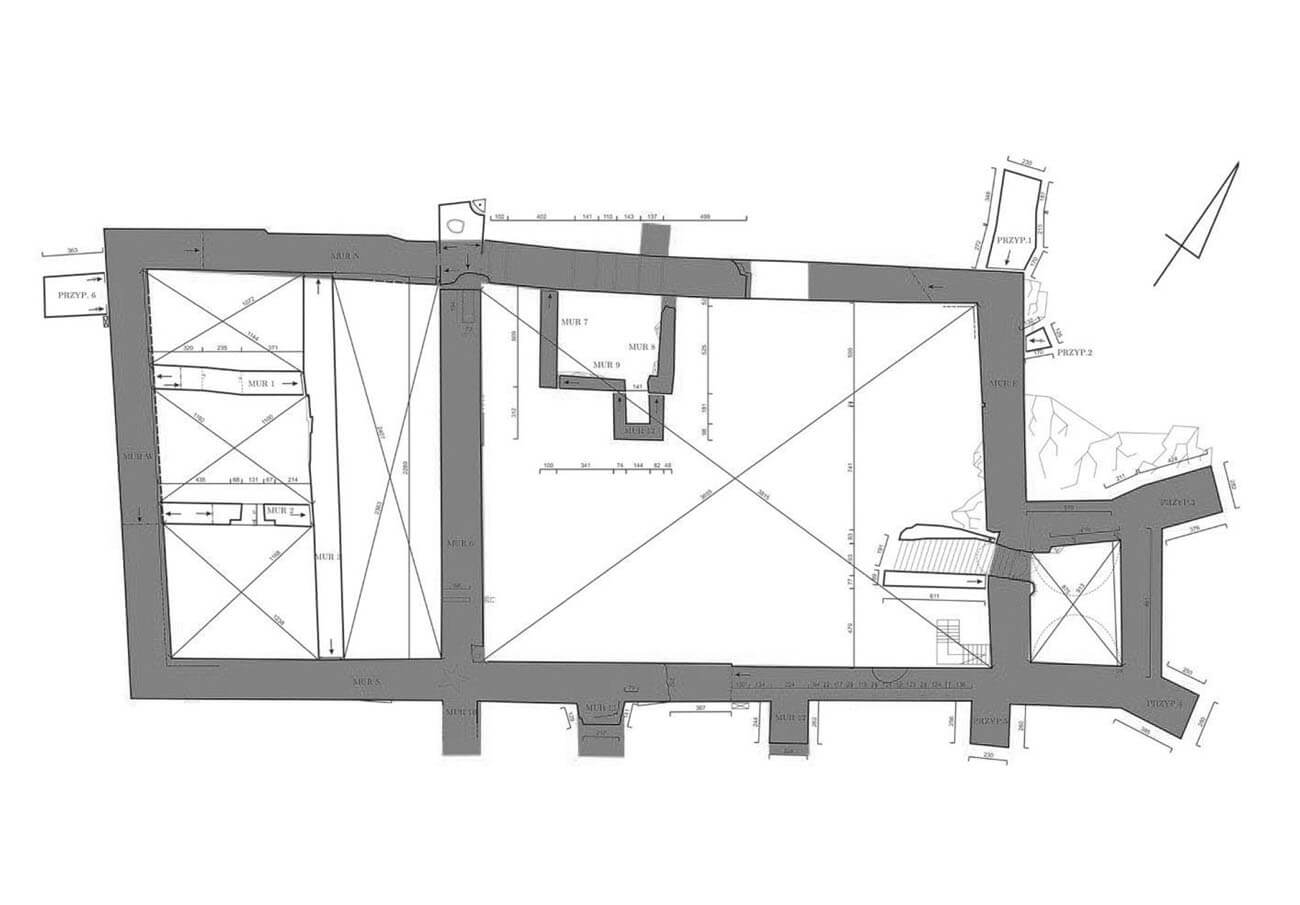

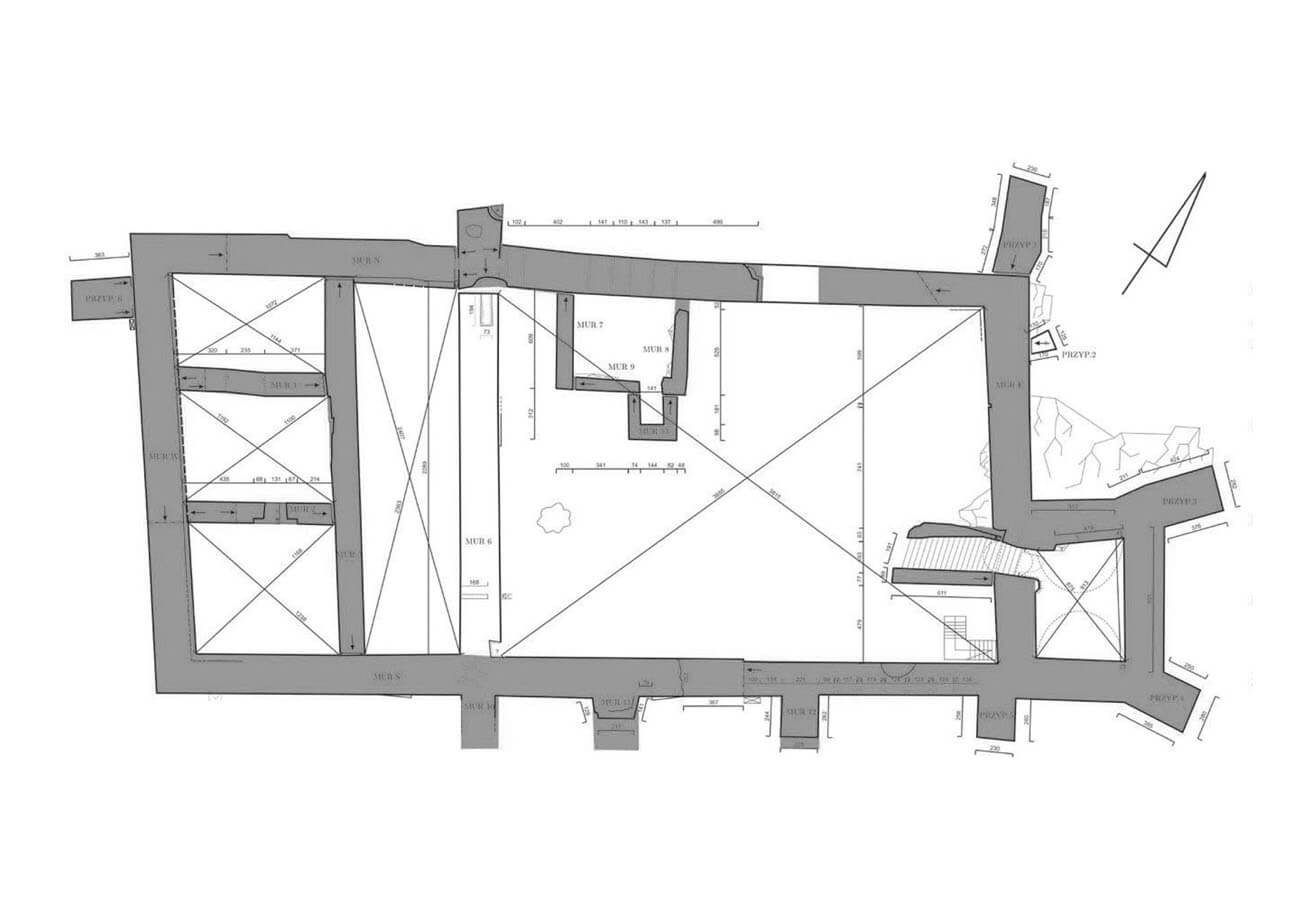

The castle had a rectangular shape in plan, with a length of approximately 57 metres and a width of 27 metres on the eastern side and 30 metres on the western side. Its perimeter was delimited by massive walls with a thickness of 2 to 2.5 meters, reinforced from the outside with irregular placed buttresses (especially from the side of steep southern slopes). In some sections of the wall were large, square putlog openings, were scaffolding functioned at the time of construction, which could be used later to erect more solid structures, e.g. hoarding porches. The main elements of the castle were two buildings located on the opposite sides of the courtyard from the east and west. The walls were built of local sandstone and of river boulders to a lesser extent, in the opus emplectum technique, using clay and lime-sand mortar for bonding. The walls were often built on rock, without foundations or with foundations only on some sections.

The eastern tower was built of carefully selected blocks of sandstone, laid in layers and joined with lime mortar. It received a plan of quadrangle with dimensions of about 10.3 x 12.2 meters and walls almost 2.5 meters thick. In the eastern corners it was reinforced with massive buttresses, and its ground floor interior was covered with a barrel vault. The height, by analogy with other buildings of this type, could be about 16-18 meters. It was probably one of the oldest elements of a stone castle, built together with the defensive perimeter of the walls at the end of the 14th century or at the beginning of the 15th century. Due to its large dimensions, it certainly served residential functions, it also flanked the access road.

The western building was built later, probably only during the reconstruction of the castle in the second half of the 15th century or at the beginning of the 16th century. A residential house measuring 13.5 x 28 meters was then added to the curtains of the wall, created by adding a 1.8-meter-thick wall from the side of the courtyard. The interior in the lowest storey was divided into three rooms with thinner transverse walls, 1.3-1.4 meters thick. It is possible that, as in other similar buildings of this type (e.g. bishops of Bodzentyn), it had three overground storeys.

The gate to the castle was located in the eastern part of the northern curtain wall. It was probably just an ordinary portal set in the wall, closed with a door, perhaps also with a drawbridge, because a ditch had been dug on the northern side of the castle. Another gate must have been located inside the perimeter, because two-thirds of the length of the castle courtyard was divided by a transverse wall, no less solid than the peripheral walls. Perhaps in this way the western part of an economic nature was separated from the eastern, residential part. It is also possible that the walls of the western part were lower, which could be indicated not by their width, which was almost identical to the rest of the castle, but by the lack of buttresses.

In the courtyard, right next to the gate, on its western side, there was a small stone building with interior dimensions of about 6 x 8 meters. It probably had an economic function. It could have served as a granary (large amounts of grain were found) or a pantry (the lowest storey was reached via steps below ground level). Later, it could also have housed an armoury (numerous military items and riding equipment were found). The space between the building, the curtain of the defensive wall and the transverse wall was closed off from the courtyard side with a timber wall covered with clay, creating an additional room measuring 3.5 x 6 metres. The courtyard itself was probably entirely paved with flat stones. It housed a well in the north-eastern part.

During the reconstruction at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the transverse wall was dismantled. Most likely, at that time, buildings were also added to the defensive wall in the eastern part of the courtyard, between the stairs to the basement of the quadrangular main tower and the northern curtain. It contained two rooms, the northern of which was lower than the southern one, due to the slope of the terrain. Their front wall was built of wood on a stone base, while the partition wall was made of wood and covered with clay, and then perhaps whitewashed. The rooms housed the castle kitchen and the adjacent utility room. Their interiors contained both ovens and open hearths. Sewage was drained outside the castle through a chute located in the eastern wall at the corner buttress.

During the late medieval reconstruction, the gate was left in its old place, but it is possible that the function of the external gate was taken over by one of the buttresses, added to the north-eastern corner of the perimeter wall, which was much longer than the others. It was not placed at an angle, as was customary, but almost on the same axis as the eastern curtain wall of the castle. It certainly cut off access to the northern slope, creating a kind of foregate situated at an right angle.

Current state

Until now, the relics of the lower parts of the four-sided eastern tower has survived, along with the passage to its basement, leading from the area of the former kitchen, and fragments of stone defensive walls, in the best condition visible especially near the tower. In recent years, they have been examined by archaeologists, slightly built-up, and a viewing platform has been created at the top of the tower. Admission to the castle grounds is free.

bibliography:

Chudzińska B., Zamek w Muszynie. Stan badań do roku 2010 [in:] Zamki w Karpatach, red. J.Gancarski, Krosno 2014.

Ginter A., Zamek w Muszynie w świetle najnowszych badań archeologiczno – architektonicznych “Almanach Muszyny”, Muszyna 2014.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Muszyna – Plaveč: Odkrywamy zapomnianą historię i kulturę polsko-słowackiego pogranicza, red. A.Ginter, J.Ginter, Muszyna 2019.