History

The first, unfortified settlement was probably established near the ford on the Barycz River at the end of the 9th or the beginning of the 10th century. Around the second half of the 10th century, a stronghold was built to the south of it, and the older open settlement was transformed into an unfortified borough. From the 12th century, there was already a castellan’s seat in Milicz, but some of the local estates belonged to the Gniezno archbishopric and later to the Wrocław chapter. The first information in documents of the bishop’s stronghold (“Miliche castello”) was recorded in the papal bull of Innocent II from 1136, the next one in the bull of Hadrian IV from 1155 (“Milice”). In the mid-13th century, Milicz was still partly owned by the bishop and partly by the prince, which led to conflicts between secular and ecclesiastical authorities, resolved by an agreement in 1249. The document signed at that time simultaneously listed the bishop’s and prince’s castellans, defined their competences and income. Thanks to the stabilization of the legal situation, as well as the fact that Bishop Thomas II obtained complete exemption from servitudes, taxes and fees paid to the prince after 1290, a brick castle was founded in Milicz at the end of the 13th century. Dominating the timber buildings of Milicz, it was a symbol of the bishop’s high position. In addition to its residential function, it could also be a place of court hearings and the execution of decisions.

Around 1290, Milicz became part of the Duchy of Głogów, and in the first or second decade of the 14th century, the castle briefly became a pledge of Palatine Albert. However, in 1319, it passed into the bishop’s direct ownership. In 1337, the Czech king John of Luxembourg began negotiations to take over Milicz, but the pope forbade the bishop and the chapter from giving up the castle without his consent. In 1339 at the latest, the king forced the castellan-archdeacon Henry of Wierzbno to surrender the castle, after he had formed an armed unit at the expense of the Wrocław citizens, with which he set off to Milicz (Henry of Wierzbno was to surrender the castle in exchange for two bottles of French wine). In response, in 1340, the Wrocław bishop Nanker excommunicated the ruler. Eventually, his successor, bishop Przecław of Pogorzela, agreed to the patronage of the Czech crown over the Wrocław diocese and lifted the excommunication, while John returned Milicz to him. Also, Charles IV, Jan’s son and successor, issued a document in 1342, in which he returned the Milicz castle to the Church, renounced all claims on behalf of the Czech crown and confirmed the rights of the Wrocław diocese.

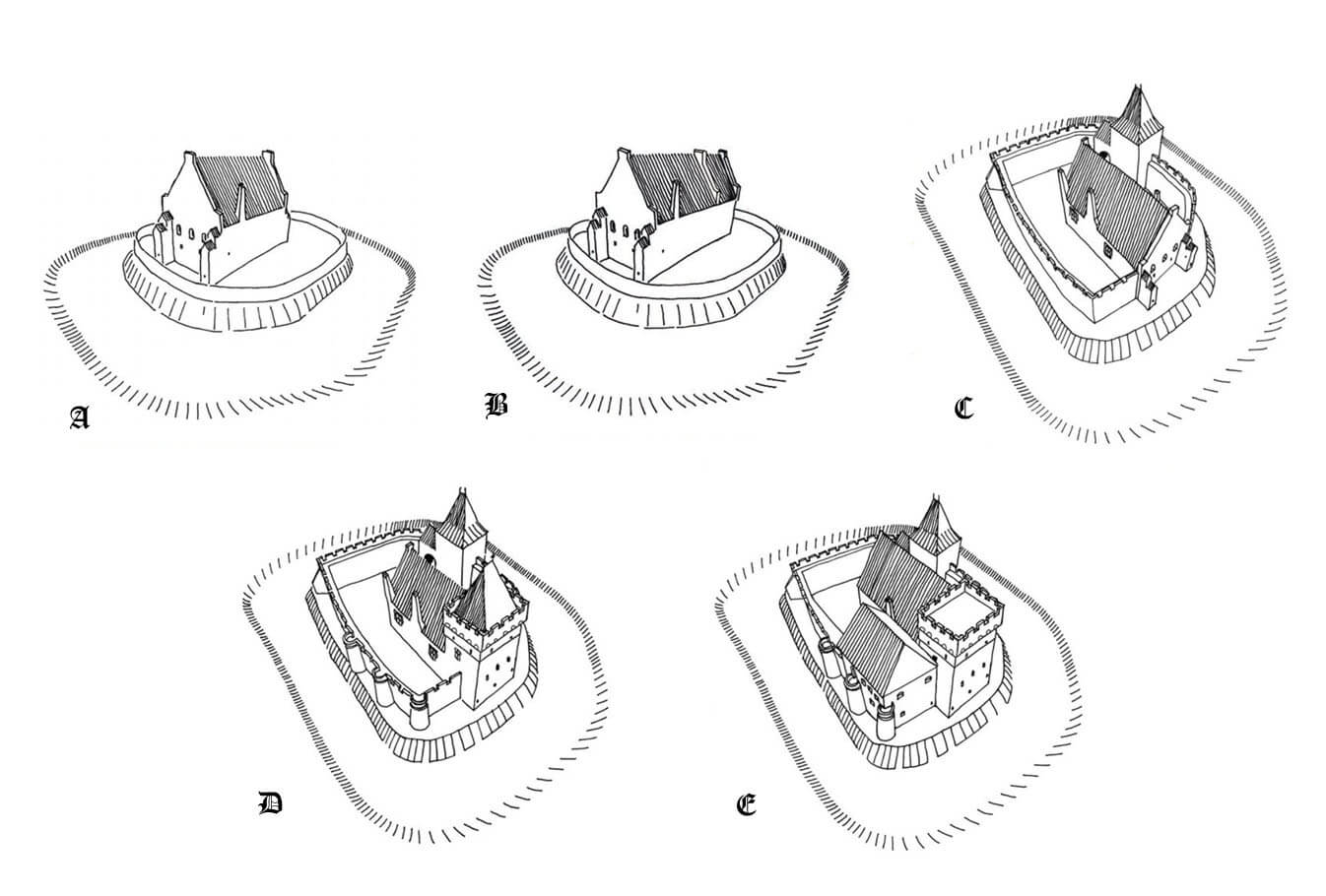

In 1358, the bishop and chapter, as the sole owners of the estate in Milicz, sold the castle, town, customs and 26 villages to Prince Konrad I of Oleśnica for 1,500 marks. The prince purchased Milicz because the maintenance costs and the necessity to pay its castellan or starost (“capitaneus”) were too high for the previous owners (52 fines “pro conservatione et custodia”), and moreover, the income was intended to expand the estate of the bishop’s Nysa-Otmuchów domain. However, the “castrum Militz” was still to be opened by Konrad at the request of the bishop or the king of Bohemia. The new owner placed his administrator in the castle, whose authority covered the entire Milicz district, including the town. Moreover, after purchasing Milicz, Konrad of Oleśnica expanded the castle, slightly increasing its living space and modernizing the fortifications.

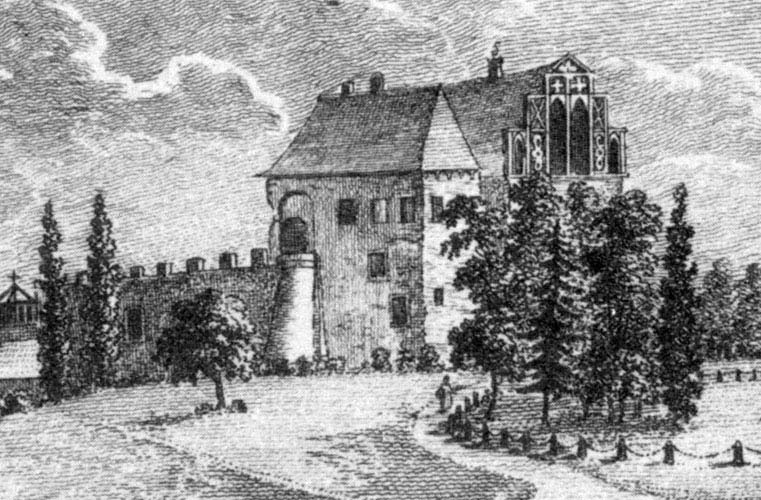

In 1432, the castle and the town were destroyed during the Hussite invasion. Rebuilt after the war, probably around the 1460s, from 1494 it was the property of Sigismund Kurzbach, royal subcamerarius and starost of Buda, who received the Milicz estate from King Vladislaus II Jagiellon. The new owner began construction work on the castle in 1508, led by Master Leonhart Gogel, and further modernization took place after the fire in 1536. In 1590, the castle came into the possession of the von Maltzan family, to whom it belonged until 1945. In the 17th century, further early modern reconstructions took place, but the castle lost its importance, especially since in 1616, after being struck by lightning, the tower (the gatehouse or the tower built in the 16th century on the southern part of the residential building) burned down and collapsed, killing five people. At the end of the 17th century, the defensive perimeter wall was dismantled, and at the end of the 18th century, a cotton mill was set up in the castle, which was destroyed by fire in 1797. Although attempts were made to repair it in the neo-Gothic style, the building was eventually abandoned by the mid-19th century and fell into complete ruin.

Architecture

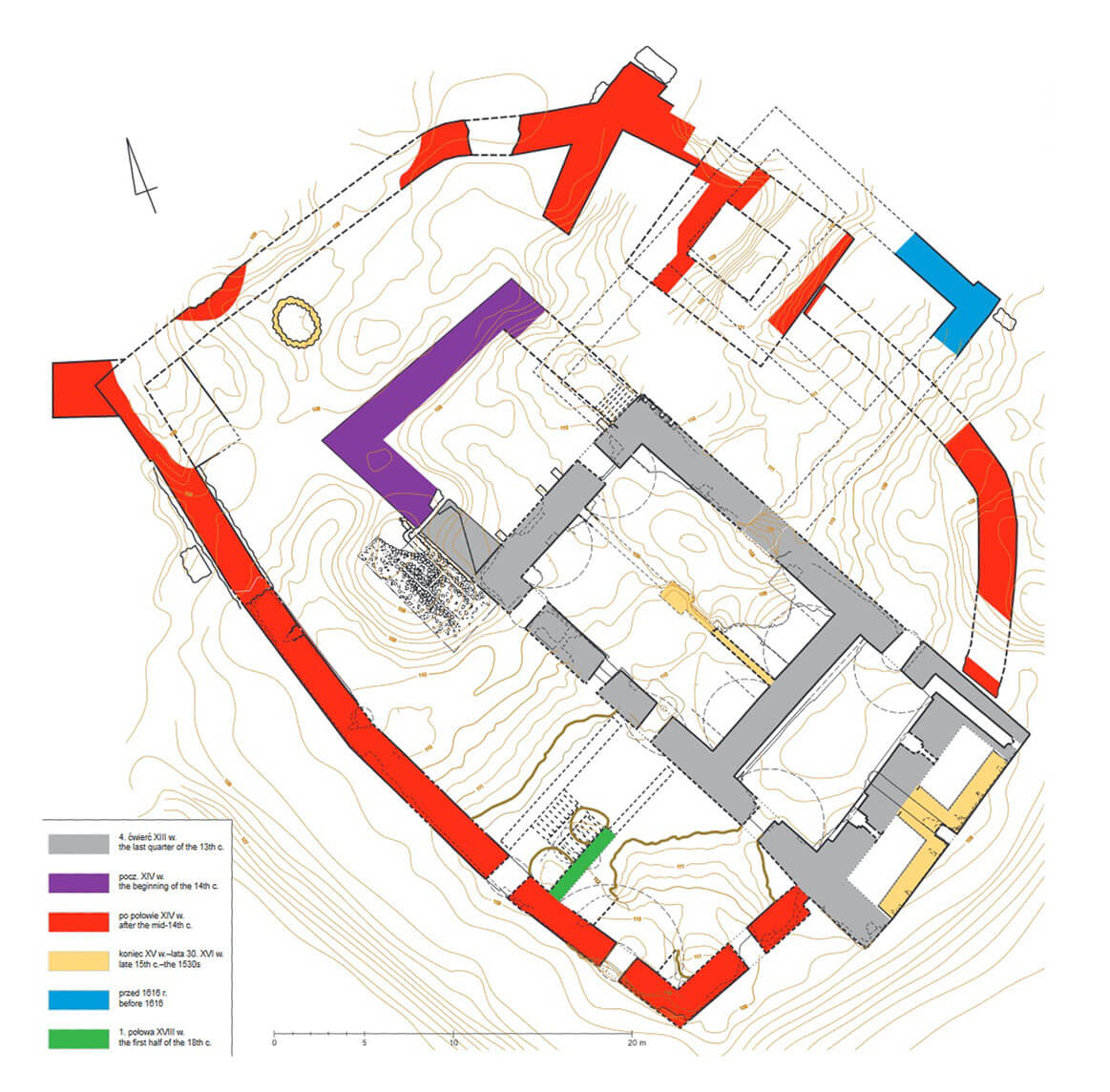

The castle was built in the Barycz River valley, on the southern side of its bed, on an artificially created plateau with an area of approximately 50 x 60 meters. It was built on a plan close to an oval, surrounded by a watered moat and an earth rampart, probably topped with a wooden palisade. The moat was created by digging through an old riverbed, probably connected by a canal. It was 15 meters wide and its banks were covered with fascine. The entrance to the courtyard must have been via a long wooden bridge, probably located in the north-eastern part of the perimeter.

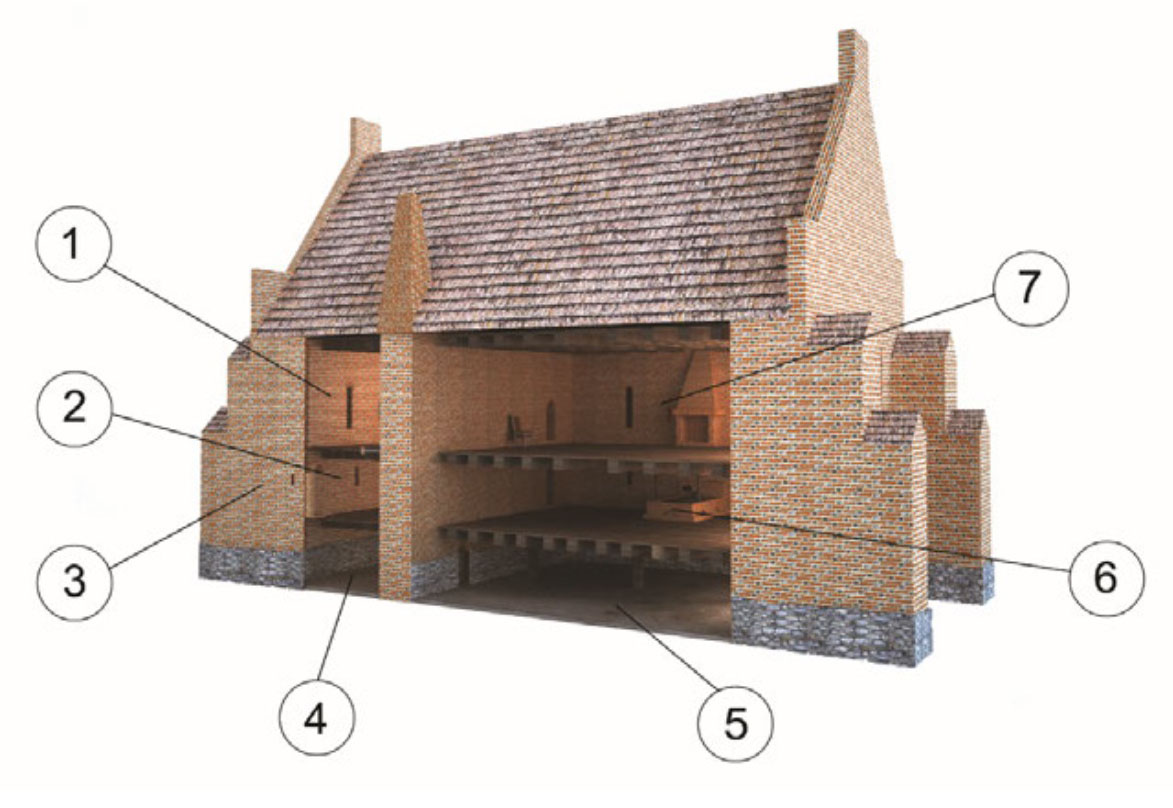

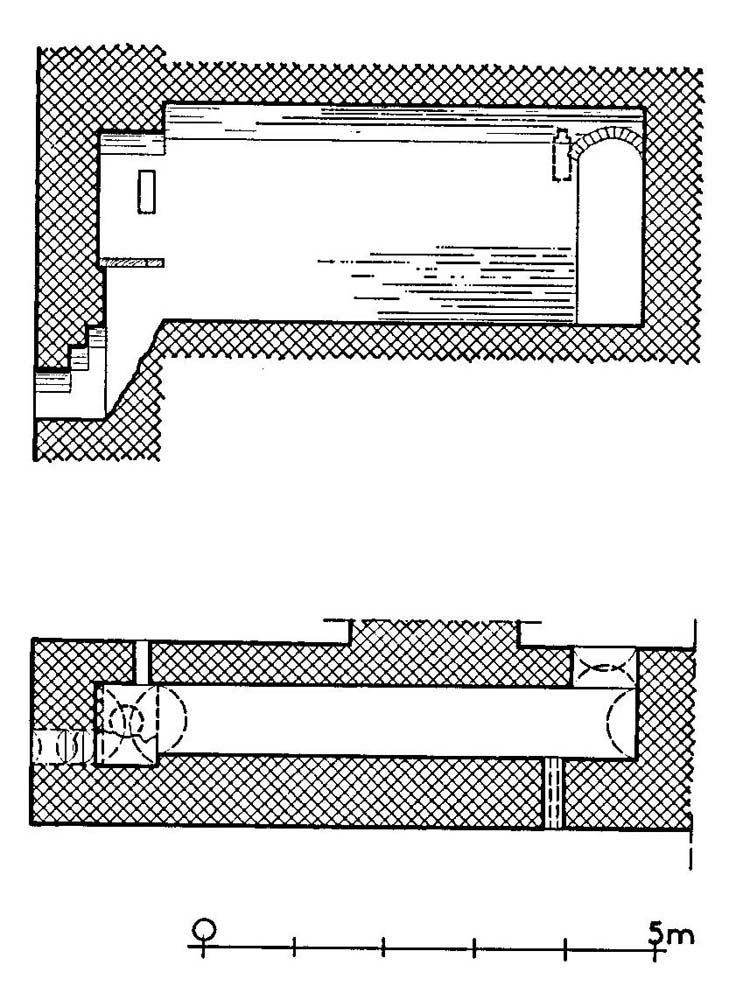

The main element of the oldest layout from the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries was a quadrangular building, elongated on the north-south axis, measuring 14.5 x 25-26.3 meters, located in the southern part of the courtyard, so that one of its shorter walls formed part of the defensive perimeter. It had three storeys, a two-part interior and four external, massive buttresses, located on the extension of the longer walls. It was built of stones on the ground floor (which was partially embedded in the embankment) and of bricks in a Flemish bond on the level of the two upper floors. The thickness of the walls in the lowest, stone parts was about 3.5 meters, while the upper, brick parts of the wall were about 1.9 meters thick. The entrance to the building led directly from the outside, via separate wooden stairs to the second and third floors, so that neither guests nor servants had to pass through the living quarters.

The interior of the castle house on each floor was divided into two rooms: smaller southern one and larger northern one, all covered with wooden ceilings. In the larger ground floor room, due to its lofty area, the ceiling could have been supported by a timber post, or this part was covered with a brick vault from the beginning. It is not known whether there was internal vertical communication between the floors, if so, it was probably in the form of simple wooden stairs pierced through holes in the ceilings. The ground floor contained two rooms for utility purposes. It probably contained pantries and stores for wine and food, as none of the rooms had windows. Alternatively, one of them could have served as a prison cell if episcopal courts were held in the castle.

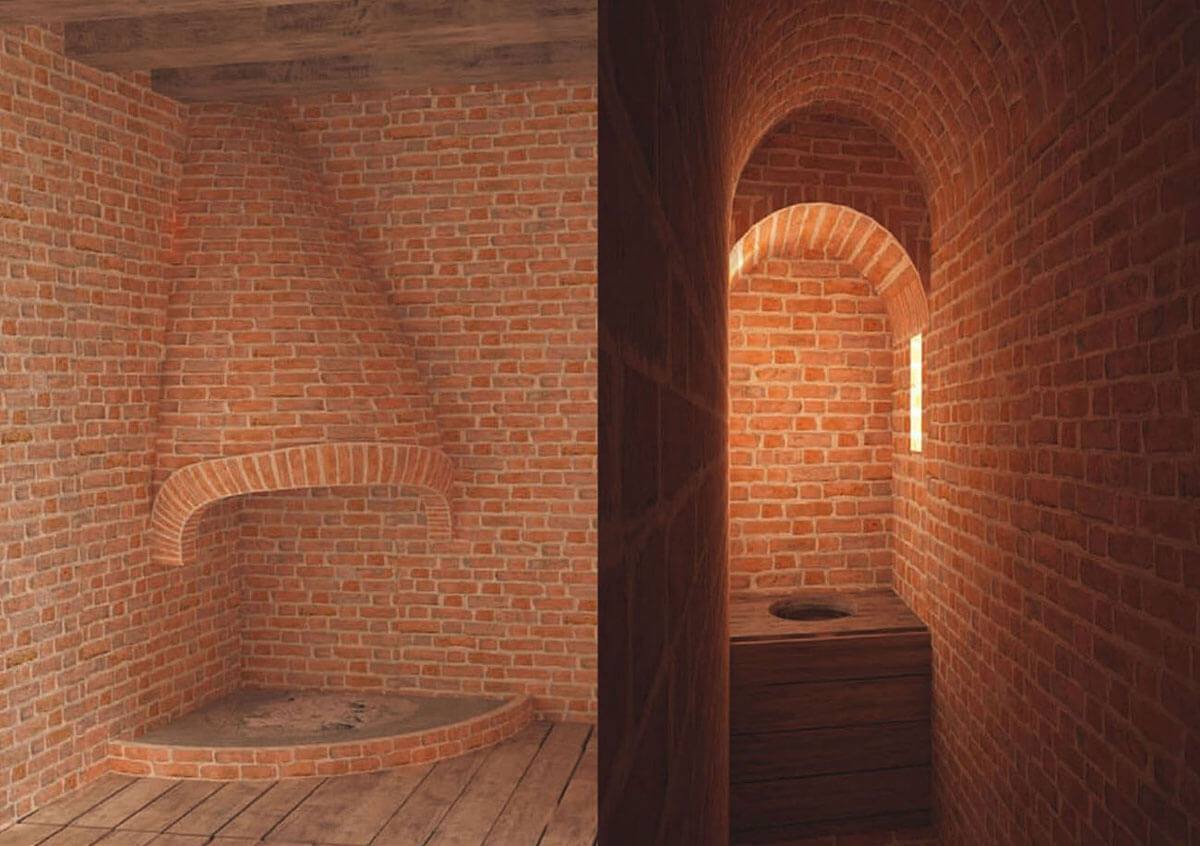

The second floor in the larger room housed the kitchen, lit by windows in the longitudinal walls and perhaps in the northern wall. The hearth functioned in the middle of the western part, probably as a clay and brick quadrangular structure with a hood to remove smoke. The smaller living room was lit from the south by two slit openings, from the inside set in niches with segmental heads, and heated by a north-eastern corner fireplace. What’s more, the room was connected to the latrine in the eastern from the southern buttresses, which was reached by a passage in the thickness of the wall, only 0.7 meters wide and 5.3 meters long. The passage was lit by two slits and it also had a small niche for a lamp or a candle. Waste was drained from the latrine through an oblique shaft covered with brick arches, directly into the moat.

On the third floor of the building, the most important room was a large representative chamber measuring 11 x 14.2 meters, heated by a fireplace placed in the middle of the western wall. The smaller southern chamber measuring 5.7-6.7 x 11.2 meters served residential purposes. It was lit by three narrow and high windows and equipped with a fireplace in the southwestern corner. The latrine for the southern chamber was created in the western buttress. The waste shaft ran vertically in it, but at the bottom it also turned into a diagonal chute. Probably in the rooms on both floors there were also various wall niches that served as shelves, cabinets, or washbasins with bowls and vessels for water.

Around the second half of the 14th century, after the castle plateau was enlarged, the residential building was extended on the northern side, obtaining the form of a tripartite palace with a length of about 37.5 meters. During the expansion, two older buttresses were used, extended, raised and closed from the north by a wall running at a slight angle. Three additional rooms were placed in the new part, one on each floor. It is possible that the larger Gothic windows were also pierced at that time. The entire house acquired considerable dimensions with a tripartite arrangement of storeys typical of the Middle Ages, probably covered with a gable roof, common to the newer and older parts of the building, but divided by the original brick northern gable.

In the second half of the 14th century or in the 15th century, the castle was expanded with a brick perimeter of the defensive wall, roughly repeating the outline of the older ramparts. In the south, the wall was connected to the corners of the house, so that its southern elevation was part of the defensive perimeter, and two buttresses still protruded towards the moat. On the three remaining sides, a narrow, paved courtyard with a well was created between the house and the wall. A quadrangular gatehouse was built in the line of the wall, located on the north-eastern side. The wall was built using the opus emplectum technique, with a core filled with brick rubble and bog iron ore, and a face made of bricks in a Flemish bond, interwoven with zendrówka black bricks, similarly to a residential building.

In the first quarter of the 16th century, the southern part of the building, probably due to its location in the line of fortifications and the desire to enlarge the living space, was built up to a tower-like form. This was done by closing the free space between the southern buttresses with a wall parallel to the gable of the house and a second, thicker wall perpendicular to it. Thanks to this, the elevation was smoothed and extended by about 3.5 meters. A little later, a beamed ceiling was installed at the lowest level, and above it two bays of barrel vaults were built, covering two small chambers connected with the older living room. The passages to the chambers were created using the old side windows, while the central window was transformed into an entrance to a passage in the thickness of the perpendicular wall between the chambers, ended with a window and a latrine shaft. In addition, during the reconstruction, barrel vaults were installed in the former southern chambers on the second and third floors, and barrel-groin vaults supported by a central pillar were installed in two rooms under the great hall. Three small, rounded turrets were built by the peripheral wall in the southwestern part of the castle.

Current state

Fragments of the brick, overgrown with vegetation walls of the medieval castle and the remains of buildings erected in the early modern period have survived to this day. The walls of the southern part have survived almost to their full height, the middle to about half height, while the outline of the northern part was uncovered during archaeological excavations. Traces of the moat that once surrounded the castle are also visible. Among the architectural details, the remains of latrines in the thickness of the buttresses are a unique elements, including the original fragment of the stone toilet cover. The original windows have survived only in fragments at the level of the second floor. The lowest floor is still mostly covered with rubble. The monument urgently needs renovation, which would make possible to visit it and, more importantly, stop its degradation.

bibliography:

Atlas historyczny miast polskich. Tom IV Śląsk, red. R.Czaja, red. M.Młynarska-Kaletynowa, red. R.Eysmontt, zeszyt 7 Milicz, Wrocław 2017.

Chorowska M., Rezydencje średniowieczne na Śląsku, Wrocław 2003.

Chorowska M., Kudła A., Architektura i historia średniowiecznego zamku w Miliczu [in:] Nie tylko zamki: szkice ofiarowane profesorowi Jerzemu Rozpędowskiemu w siedemdziesiątą piątą rocznicę urodzin, Wrocław 2005.

Kolenda J., Markiewicz M., 3D visualization as a method of a research hypotheses presentation – the case of the medieval palace in Milicz, “Przegląd Archeologiczny”, Vol. 63/2015.

Kolenda J., Markiewicz M., Medieval bishops palace in Milicz. 3D Reconstruction as a Method of a Research Hypotheses Presentation, “Studies in Digital Heritage”, Vol. 1, No. 2/2017.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Nowakowski D., Śląskie obiekty typu motte, Wrocław 2017.