History

The Legnica stronghold was one of the oldest and most important settlement centres in Silesia in the early Middle Ages. The first wood and earth buildings were built around the 8th century by the Slavic tribe of Trzebowianie. Then, around 985, during the time of Mieszko I, two-part ramparts were built in order to secure Silesia after its annexation to the Piast state. In place of this stronghold, at the end of the 12th or beginning of the 13th century, a castle was built, which was one of the first brick fortresses in Polish lands. It was the main residence of Prince Bolesław I the Tall and his son Henry the Bearded. Henry was one of the strongest princes of the era of feudal fragmentation. Having received a rich Silesian district from his father, in 1232 he took power over Małopolska and captured Kraków, and by 1234 he had taken part of Wielkopolska region. Although he failed to seize the crown, he organized a magnificent center, equipped with architectural attributes associated with royal power since the Carolingian era, such as a brick palas with a great hall and a chapel, built in the 1220s. Initially, the prince wanted to establish his seat in Henryków, but eventually decided on Legnica, a stronghold located in the vicinity of the intensively colonized and economically vibrant areas of western Silesia. Perhaps this choice was also related to the desire to leave Wrocław and move away from the center of episcopal power.

The oldest records of the castle buildings appeared in 1149, when Prince Bolesław the Curly gave the chapel of St. Benedict in Legnica to the abbey in Ołbin in Wrocław, and in 1193, when the chapel in Legnica was mentioned as the property of the Ołbin Abbey. In 1201, the chapel in Legnica under the dedication of St. Laurentius, while in 1253 a double dedication of the chapel of St. Benedict and Laurentius was recorded. The castle itself was recorded in documents in 1241, and in 1256 and 1257 it was mentioned together with the towers.

With the death of Henry the Bearded in 1238, Legnica passed to his son Henry the Pious. He continued to rebuild the castle into a fully brick structure, but this work was interrupted by the Mongol invasion in 1241. However, the strength of the Legnica castle was already great enough to successfully defend itself against a siege. In 1249, during the division of Silesia, Legnica passed to the son of Henry the Pious, the young Bolesław the Horned. The ruler knew Legnica castle quite well, as he had previously been imprisoned there by his brother Henry III. In 1256, he himself used a cell in one of the castle towers to imprison the Bishop of Wrocław, Thomas I. A year later, however, the castle guards failed to protect him from being kidnapped from Legnica by his brother, Prince Konrad.

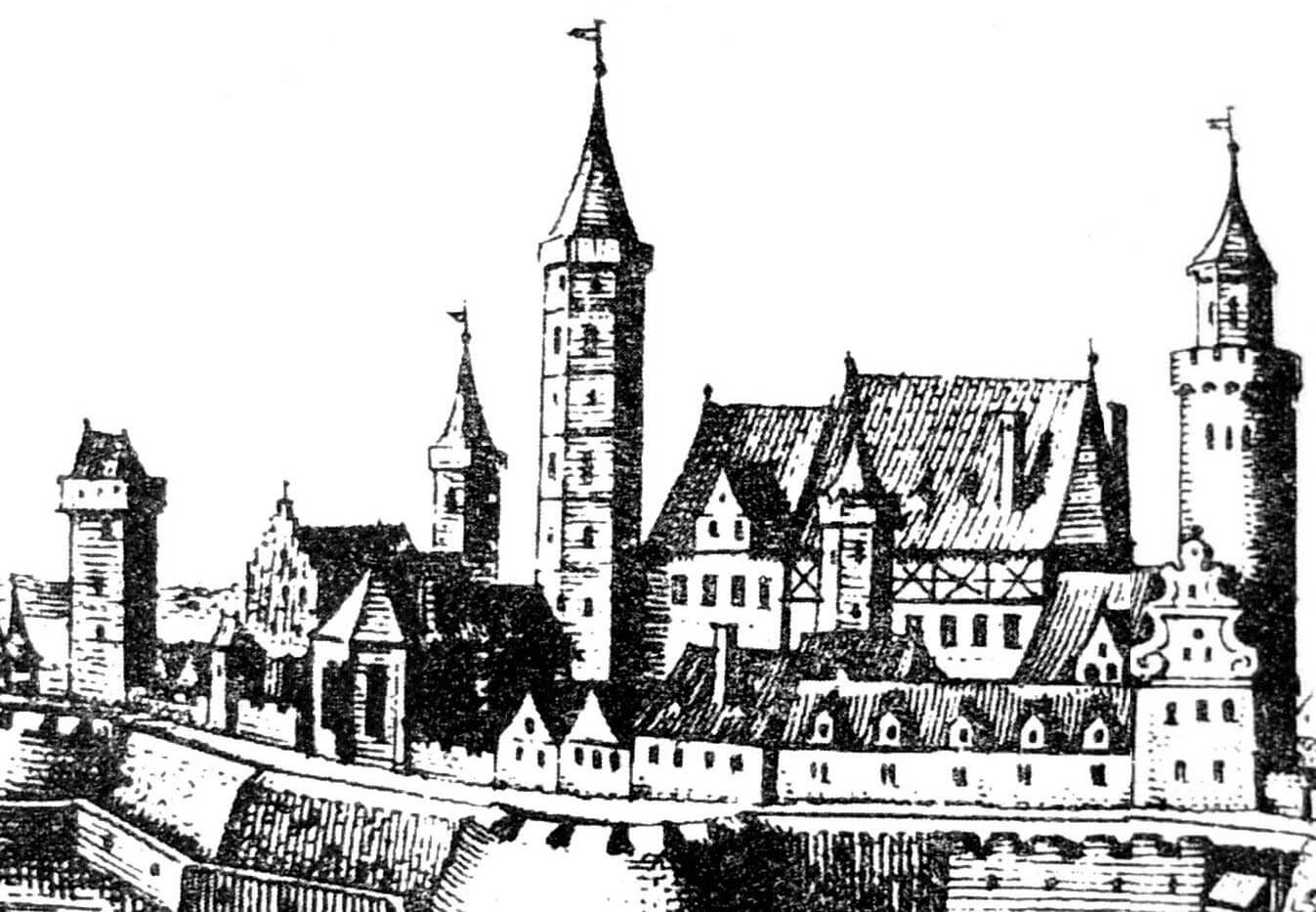

In the first half of the 15th century, the Prince of Legnica, Louis II, initiated the reconstruction of the castle, which was to improve the comfort of the old-fashioned, too poor and uncomfortable seat at that time, and to raise its towers so that they would become a visible sign of the ruler’s prestige. While staying in Saint Denis near Paris in 1416, he hired an architect, then sent an appropriate sum of money, designs and a stonemason to Legnica. He also asked the burgrave and the city council to carry out all the work according to the plans. The reconstruction of the castle was continued by Frederick I, under whom the Romanesque palas was transformed in the late Gothic style, and in the years 1527-1533 by Frederick II, when Renaissance forms began to be introduced to the interior design of the building, while the fortifications were reinforced with ramparts and four corner bastions. Then, at the end of the 16th century, a Renaissance building was erected, filling the space between St. Peter’s Tower and the palas. Its addition and the reconstruction of the palace were probably related to the lively social life that was held at the castle at that time. It hosted many rulers, and numerous receptions and feasts were organized. Among them was the wedding of Prince Henry IX to Sophia, daughter of George Hohenzollern in 1560, or a five-day feast on the occasion of the visit of Emperor Maximilian, which was supposed to be attended by over two thousand guests.

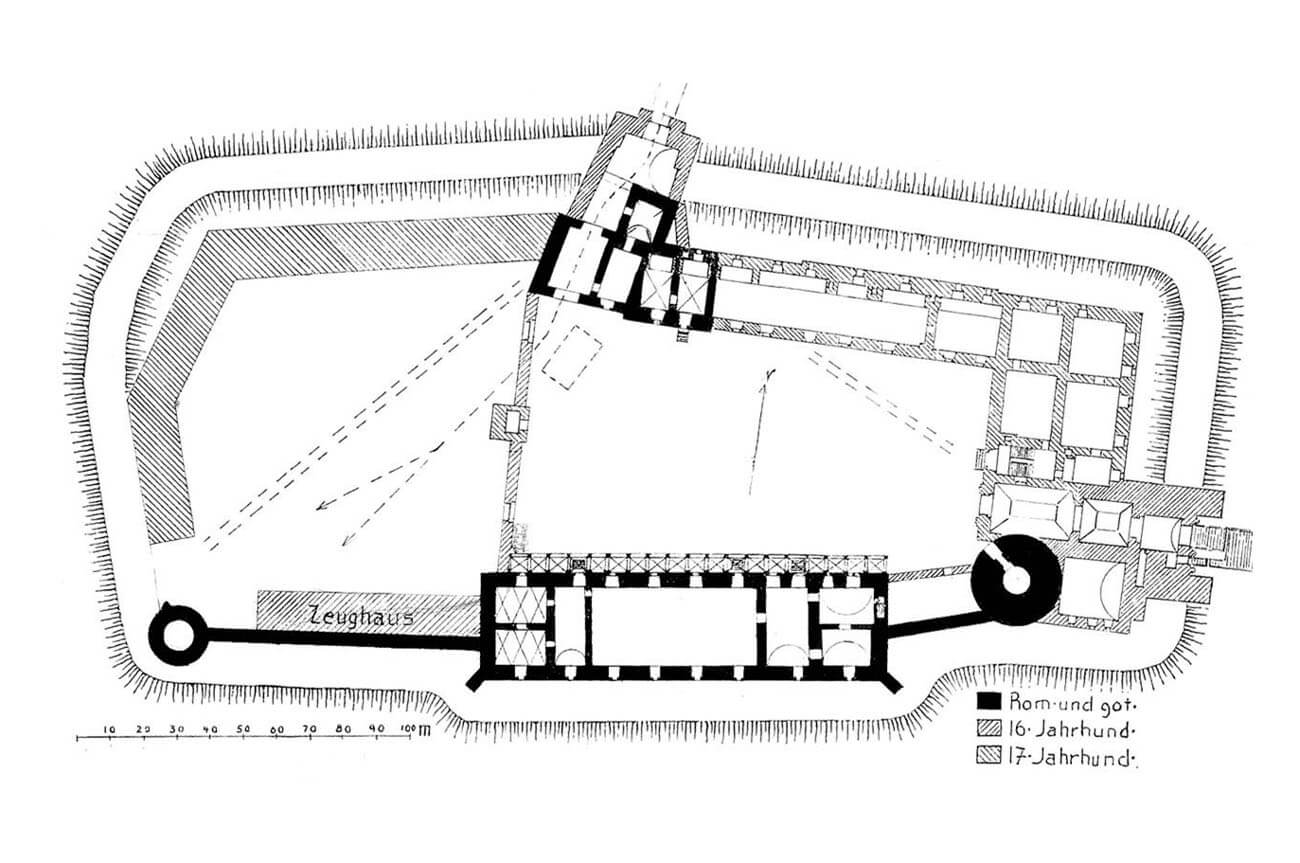

The greatest changes to the castle’s architecture were made in the first half of the 17th century. Prince George Rudolf ordered the demolition of part of the medieval buildings, including the defensive wall from the north, and in 1621 he slightened the magnificent Romanesque palace chapel. However, he funded the early modern northern and eastern wings, closing the courtyard with the clock tower from the west. In addition, the northern gate was rebuilt and a long arsenal building was erected in the economic part of the castle. The modernization and transformation of the castle in the late Renaissance style lasted until the 1670s. In 1675, when the Legnica-Brzeg line of Piast dynasty died out, the castle came under the rule of Habsburg governors, and the introduction of further changes to the development slowed down. It was not until the residence was destroyed by fire in 1711, that the subsequent reconstruction gave it the character of a Baroque palace. Subsequent fires affected the old castle in 1835, 1840 and for the last time in 1945. The last reconstruction of the castle was carried out in the 1960s.

Architecture

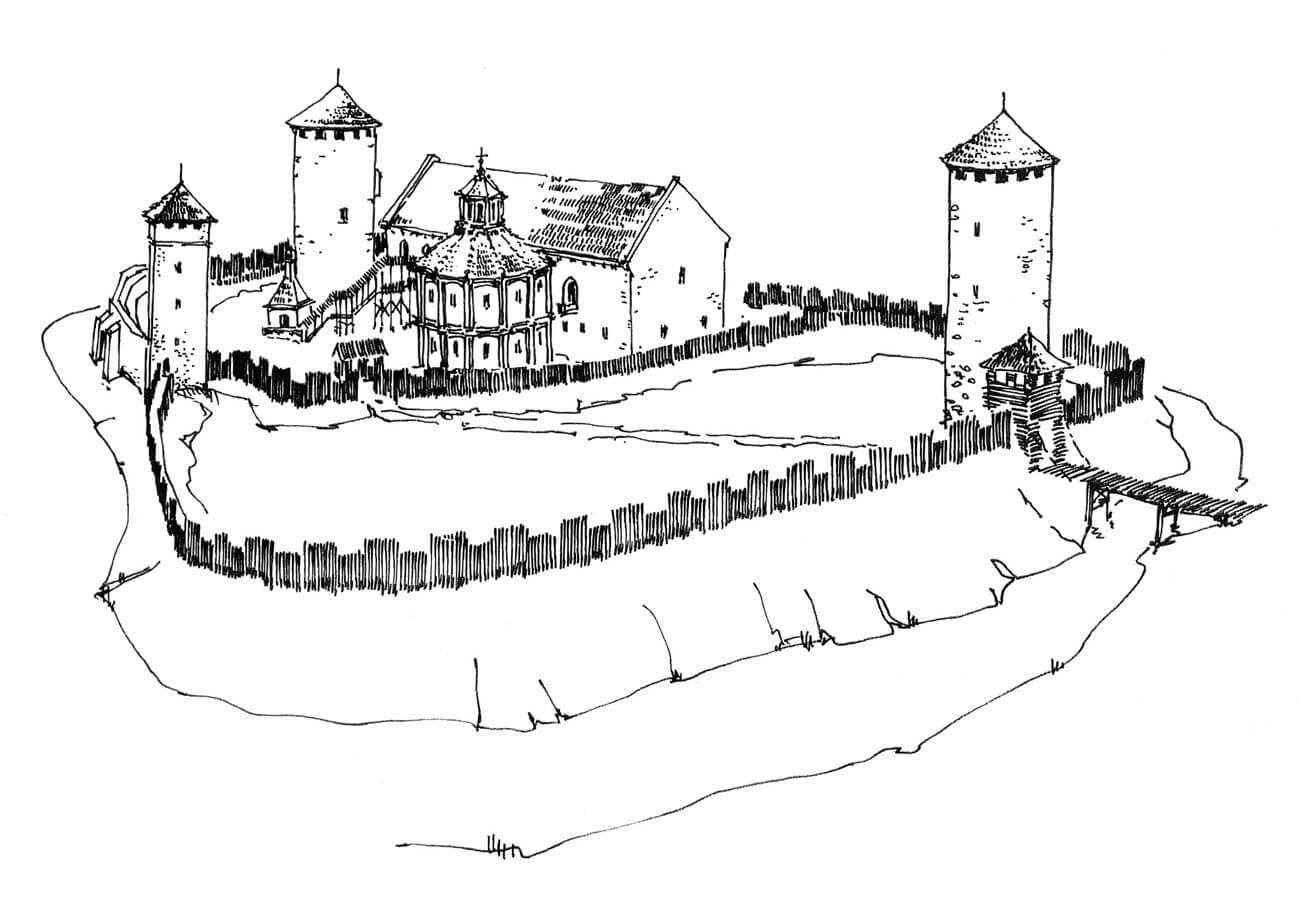

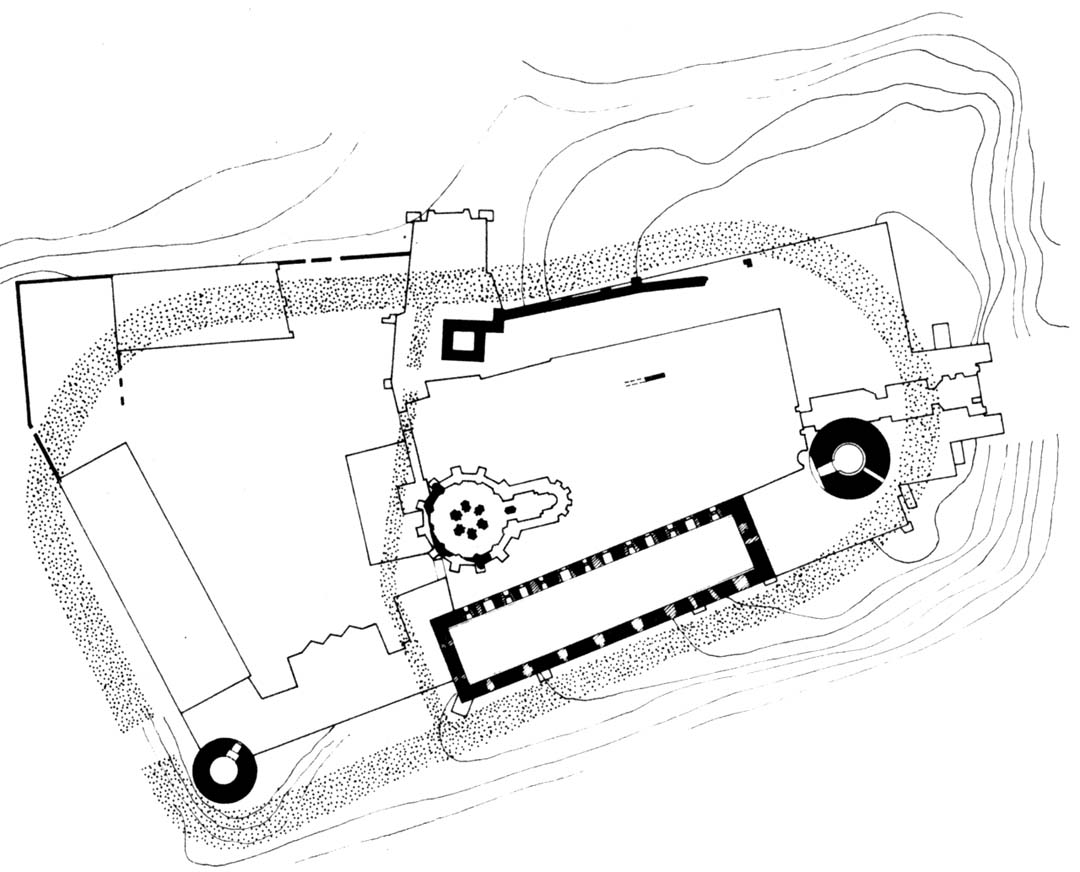

The castle from the beginning of the 13th century was situated on the site of an older stronghold, on the western side of the Kaczawa River and on the southern side of the Czarna Woda River that flows into it. It consisted of a circuit of wood and earth fortifications outlining an elongated shape on the east-west line with rounded corners. Inside the circuit, a transverse fortification divided the castle area into two parts: a slightly larger eastern one, where the most important residential and representative buildings were concentrated, and a smaller western one with the character of an outer bailey, perhaps with the castellan’s house. A settlement was formed on the southern side of the castle, and then a fortified town, whose defensive walls were connected to the castle from the east and west at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries. The town and the castle were separated from each other by a moat.

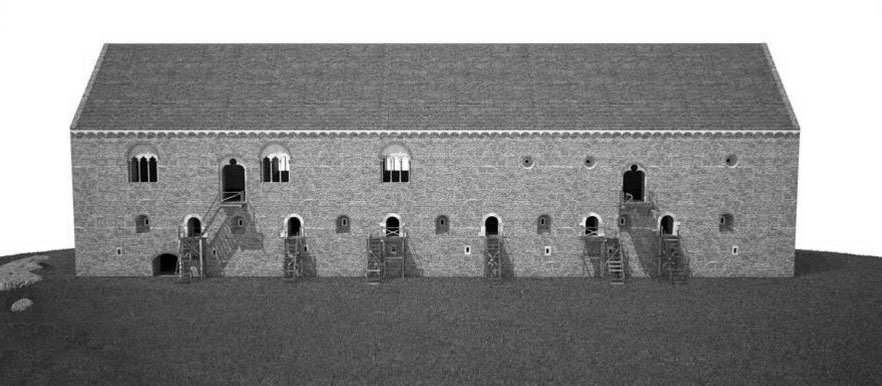

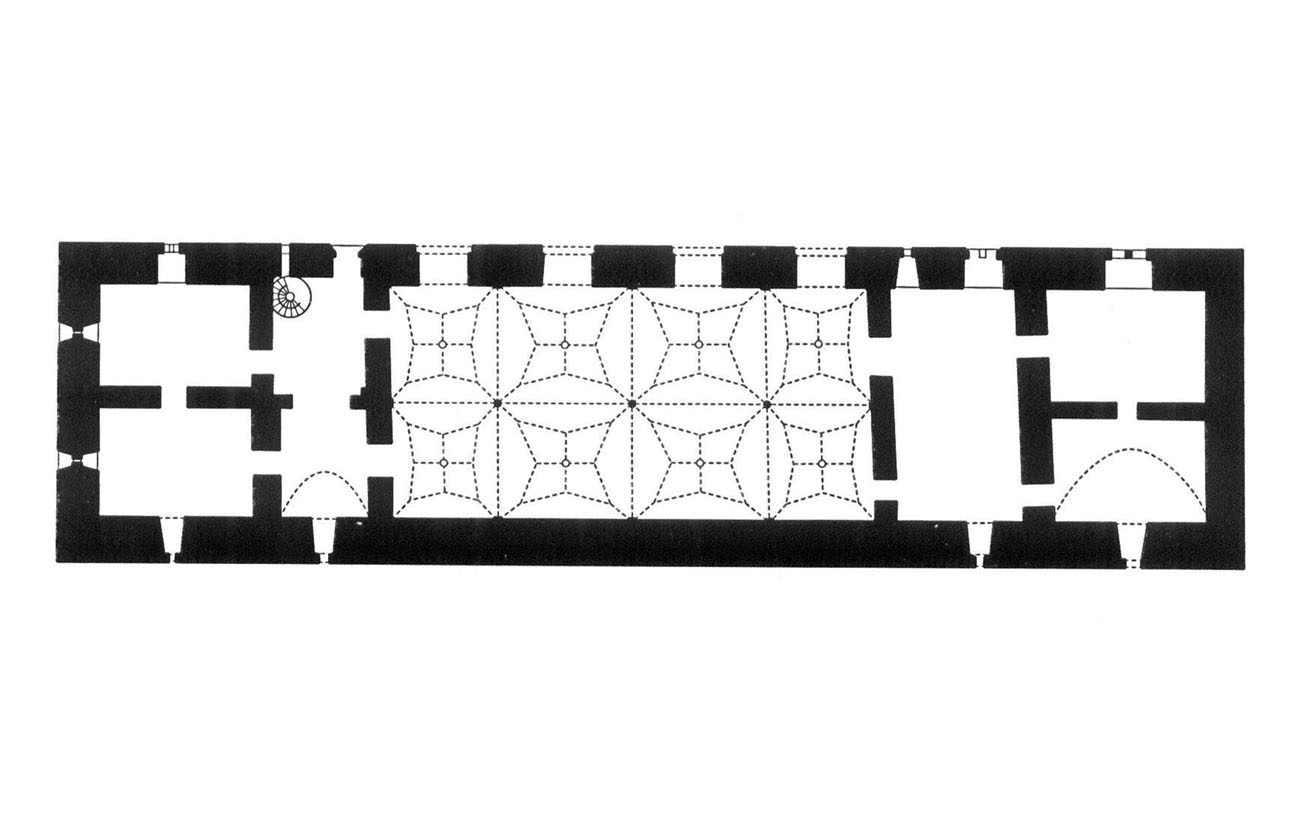

In the southern part of the castle, parallel to the fortifications with its longer sides, there was a large Romanesque palace measuring 16.1 x 61.5 meters, built of bricks laid in a monk bond, with carefully jointed elevations and sandstone window and portal frames. Due to the unstable ground, the building was built along the longer sides on strong stone foundation pillars, between which ten arches of bricks and flat stones were stretched. Above ground, the building was three-storey, about 12 meters high from the level of the courtyard to the crowning cornice, with peripheral walls 2-2.1 meters thick (the external southern wall was slightly thicker than the northern wall facing the courtyard). The whole was covered by a gable roof, supported on triangular gables on the east and west.

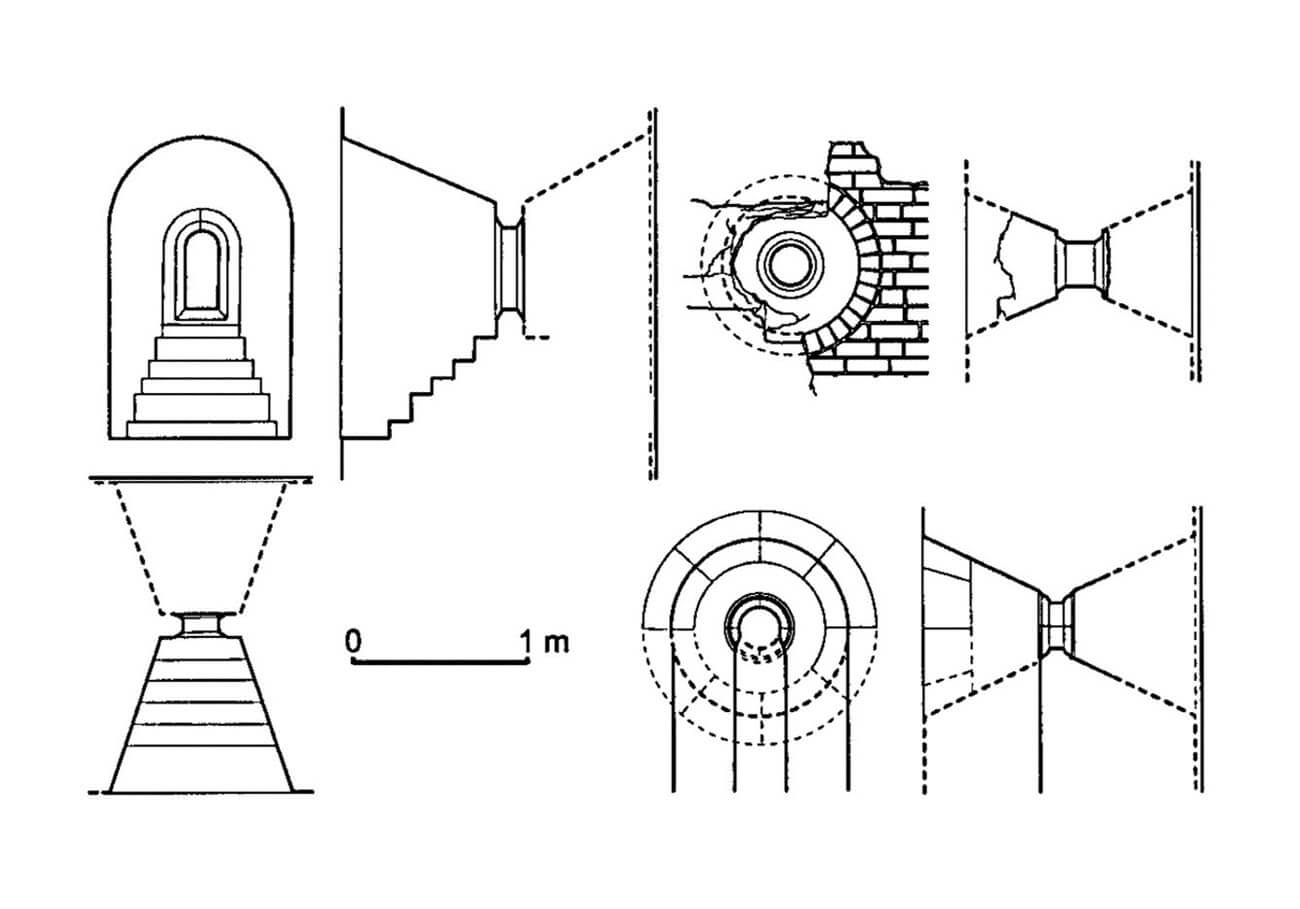

The lowest storey of the palas had an economic function. From the courtyard side it was illuminated by nine slit openings splayed towards the interior, while from the south there were no openings, because the palace wall was directly adjacent to the earth rampart. Two slit windows also illuminated the ground floor from the east and west through the shorter walls of the building. The entrance led from the courtyard through a wide, segmental portal, located at the eastern end of the northern elevation. The entire lowest floor was covered with a wooden ceiling, based on a beam running along the building, supported by wooden pillars and probably divided by light screens into smaller interiors containing pantries.

Above the utility ground floor there was a residential first floor, 2.5 meters high. From the courtyard side it had a row of alternating entrances and small, splayed windows. Six entrances were enclosed by sandstone portals with semicircular heads, and seven windows were also semicircle. This would allow to assume that the first floor was originally divided into six rooms by screens, one of which was lit from the courtyard side by two windows, and the others by single windows, with both windows and doors being lockable (the doors were equipped with bars). Since the portals were located at a height of about 3.5 meters above the courtyard, wooden stairs must have led to them. The first floor was covered similarly to the ground floor – with flat wooden ceilings.

The second floor of the palatium, judging by its 6-meter height, was occupied by a representative hall and three princely chambers. In the eastern part there was a great hall with maximum dimensions of 32 x 13.5 meters, lit by six impressive, semicircular, two-light openings placed opposite each other, created three on the north and three on the south. These openings, about 2.5 meters wide and over 3 meters high, were closed from the inside with wooden shutters, blocked by long bars set in holes in the wall. The interior of the hall was probably divided into two aisles by pillars and covered with a beamed ceiling. The entrance was located centrally in the northern wall, from where it led directly from the courtyard. In addition, in the thickness of the eastern wall there was a barrel-vaulted passage, only 0.8 meters wide, equipped with a small slit opening and a piscina. It probably led to the latrine. The western part of the second floor of the palatium was occupied by three princely chambers. Their lighting was provided by round openings pierced from the north, as well as one large southern window, similar in form to those used in the hall. Only one portal led from the outside to the residential chambers, located opposite the castle chapel. Inside, one of the rooms was heated by a corner fireplace, while another passage in the thickness of the wall led to the latrine (it may have connected two rooms).

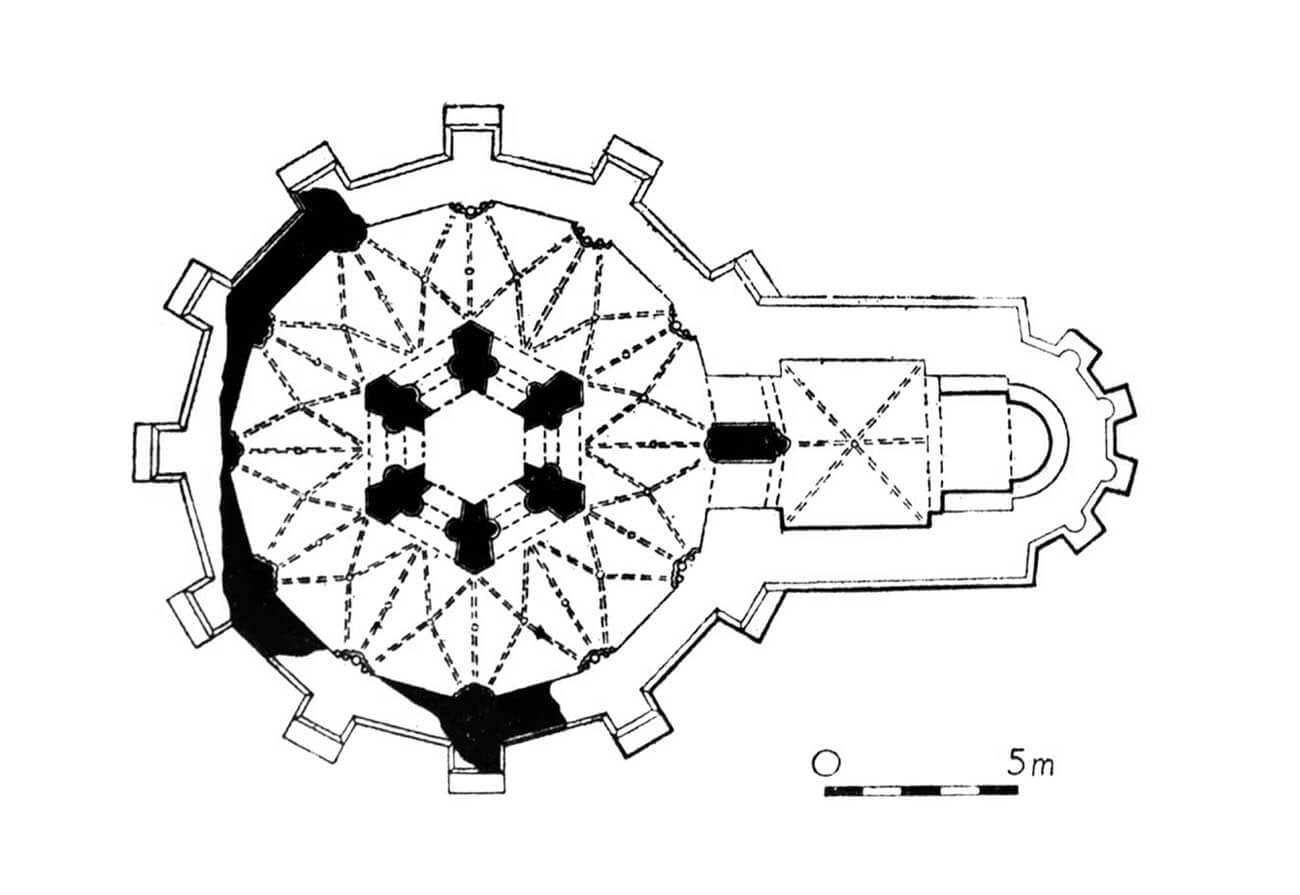

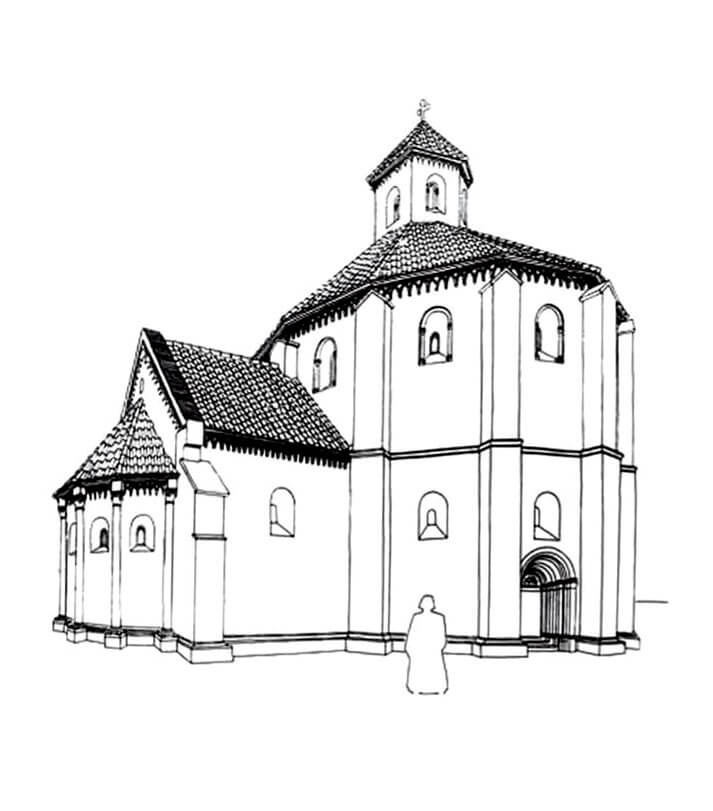

At the northern elevation of the palace since 1220-1230 there was a chapel, one of the most magnificent sacral buildings at that time in terms of spatial layout and architectural decoration, without any equivalents in other parts of Poland, modelled on the Rhineland architecture of that time, with possible influence from the Templar chapels. It was built of bricks in the monk bond, except for the pillars and architectural details made of sandstone ashlars. It was a free-standing, one or two-storey building on the plan of a regular polygon with a diameter of about 12.5 meters, with a nearly square chancel separated in the east, ended with a polygonal apse. The eastern part, i.e. the chancel and the apse, had dimensions of 4.3 x 7 meters. The external polygon was measured out extremely rigorously, because its regularity was not broken even when solving the difficult problem of connecting the nave of the chapel with the chancel. The walls of the chapel were surrounded from the outside by a moulded stone plinth and supported by corner lesenes – buttresses. In addition, the external elevations were decorated with late Romanesque friezes. The nave of the chapel was probably crowned by a steep roof with a lantern, while the chancel was covered with a gable roof.

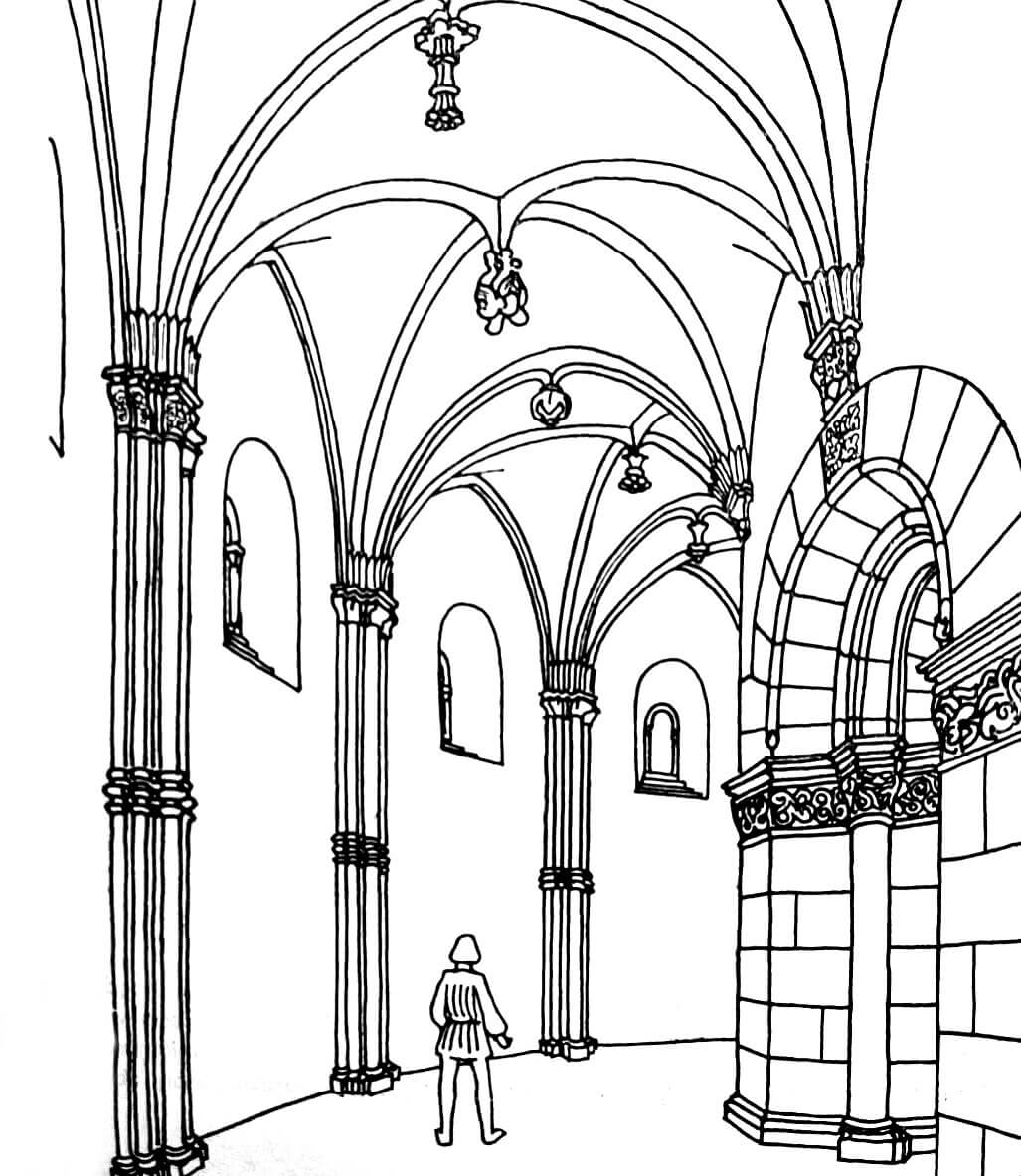

The interior of the chapel nave was designed on a hexagonal plan with a dodecagon-shaped ambulatory (circular aisle), while the apse inside had a semicircular shape. The chancel arcade connecting the nave with the presbytery was doubled, with a rarely used pillar on the axis (thanks to it, the principle of the correspondence of one hexagonal wall to two dodecagonal walls and the unchanged rhythm of the vaults were preserved). Six wedge-shaped pillars, set centrally in the polygonal interior, separated the circular aisle from the narrow, opened central space. The chancel and the circular aisle were plastered and covered with cross-rib vaults. Its structure supported from the outside by small buttresses, pointed arches between the bays and fully developed, richly moulded ribs, testified to the use of Gothic techniques, while the stylization of the ornamentation of the bases, plinths, capitals, cornices and bosses belonged to the late phase of Romanesque. The hanging bosses were particularly lavishly shaped, with representations of dragons, birds and various plant motifs. The capitals supporting the archivolts of the arcades were decorated with semi-palmette braid. The friezes with semi-palmette, lily, rosette, acanthus motifs, carved very plastically or even openwork, showed great richness of plant ornamentation. The corner shafts, of which the larger, central one supported the transverse rib, were topped with corinthine capitals. In the lower part, but only on the side of the ambulatory, there was a moulded stone plinth, which, together with the 0.5-meter difference in the level of the raised central part, architecturally emphasized the body of the building.

The chapel’s chancel probably had one level, while the nave could have housed a second storey, as indicated by the thickness of the walls, the proximity of the palatium and the similarity of the plan to other central two-storey buildings. In such a case, the upper floor would have housed the prince’s private chapel, which could have been connected by a porch to the residence, while the open central part of the chapel, lit by a lantern, could have been intended for the placement of relics or a baptismal font. On the other hand, the single-storey chapel would be indicated by a departure from the principle of gradation of interior decoration applicable in double chapels (in Legnica, the architectural decoration was too rich for the ground floor), while the considerable thickness of the wall could have been necessary due to the vaults. Moreover, the internal hexagon formed by pillars did not have to form an opening in the floor of the second storey, but could have directly supported the lantern.

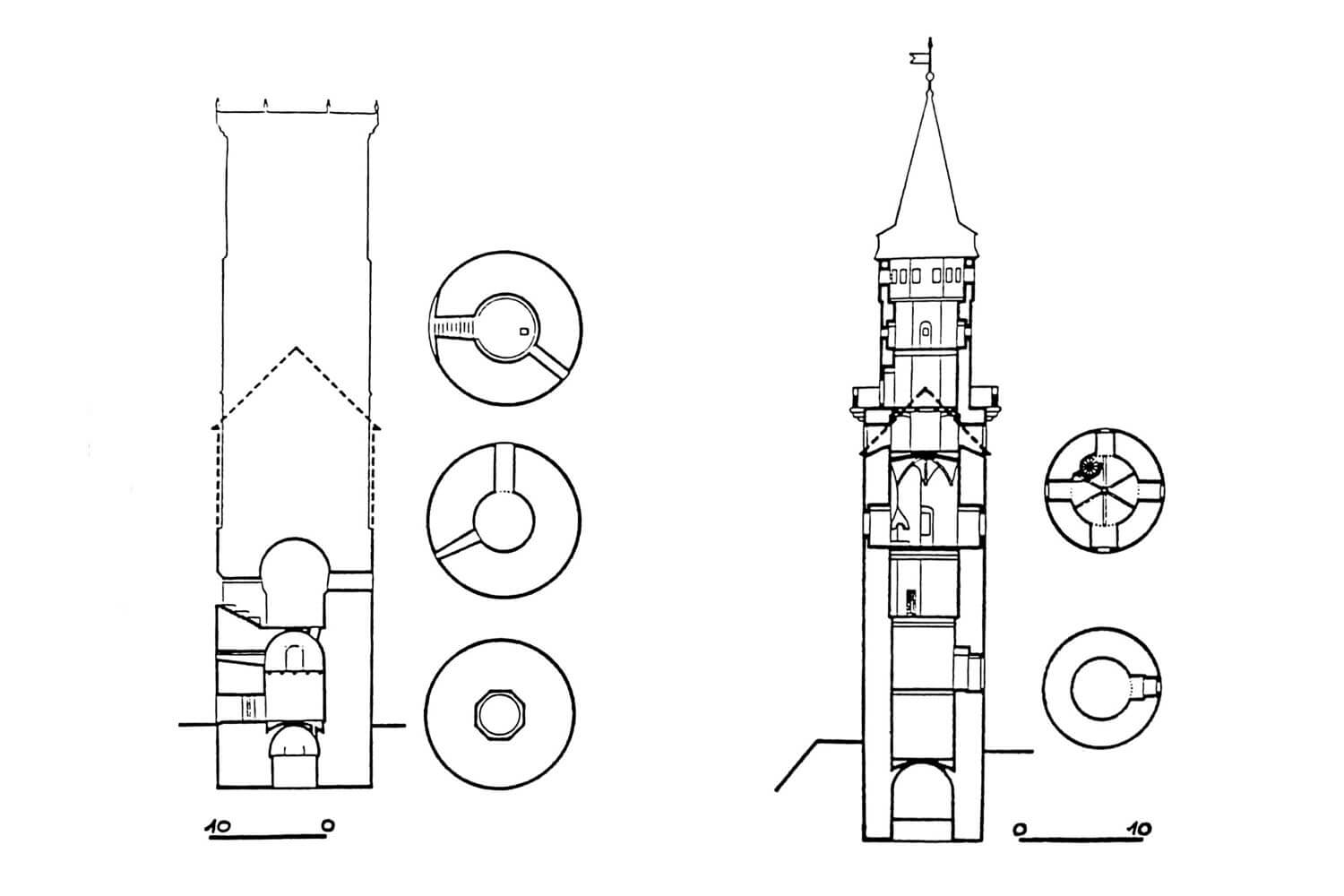

In the first half of the 13th century, three defensive brick towers were built on the castle grounds, which reinforced the older, wood and earth rampart surrounding the entire complex. On the eastern side, in the main part of the castle, a cylindrical St. Peter’s Tower was erected, located about 14 meters from the palatium. The smaller western courtyard and the entrance gate to the castle were protected by the cylindrical St. Jadwiga’s Tower, located in the south-western corner of the ramparts. The third tower, called Lubińska, stood at the northern section of the defensive perimeter, where it probably flanked the passage connecting the two parts of the castle and at the same time guarded the main perimeter of the ramparts. It was the only one connected to a short section of the brick defensive wall since the moment it was built. It was also the only one that did not serve as a bergfried.

The eastern tower of St. Peter was built on a circular plan with an internal diameter of about 5 meters, with walls thick 4.5 meters at ground level. It originally reached a height of about 25 meters. In its ground floor there was a prison covered with an octagonal vault, the top of which turned into a dome. It was the base of the floor of the upper storey of the tower, which was probably intended for guards or another cell. Both rooms were connected by small, round holes punched in the vault of the ground floor. Above it was the entrance storey covered with a wooden ceiling. On the highest storey of the tower there was a heated living room, above which in the Romanesque period there was only a defensive gallery with battlements. The heated chamber was probably intended to be the last refuge for the prince and his family in the event of the castle being captured by enemies.

The St. Jadwiga’s Tower had an internal diameter of 6 meters with walls 2.5 meters thick, so it was slightly less massive. In the 13th century it reached a height of about 20 meters. The lowest floor housed a cell, the entrance was located approximately at the height of the crown of the ramparts, the next floor was occupied by a heated living room, and above it there was a defensive gallery. Compared to the St. Jadwiga’s Tower, the tower called Lubińska had much more modest dimensions. It was built on a square plan with sides about 4.6 meters long and walls only 1 meter thick. For this reason, it was probably the lowest of the three towers.

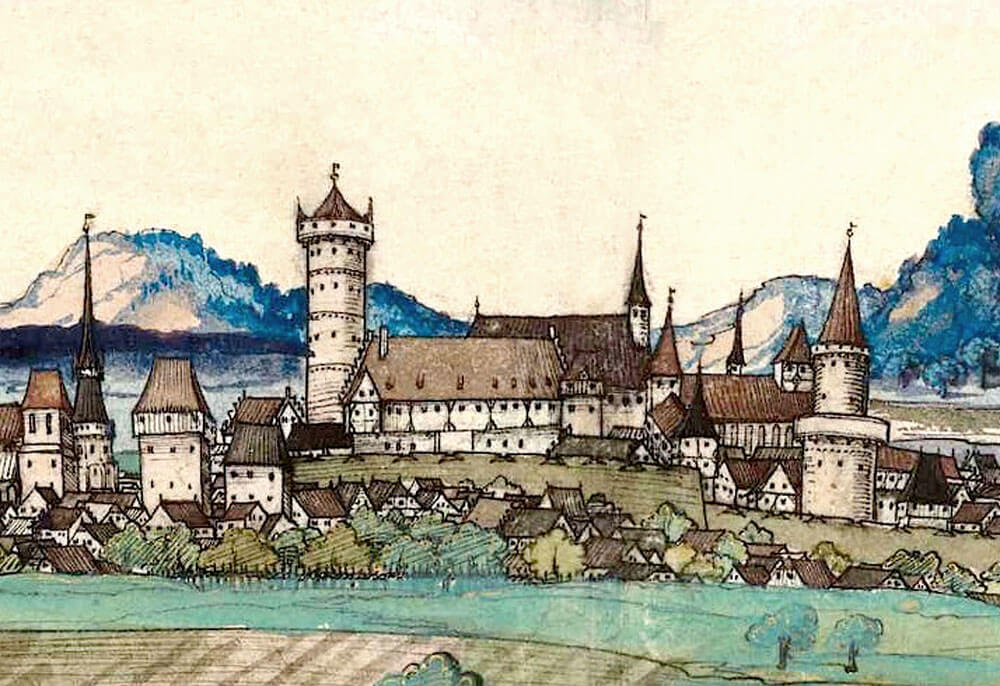

In the first half of the 15th century, St. Peter’s Tower was raised by a polygonal part about 30 meters high, which made it almost twice as high. The elevations of the Gothic part were divided by narrow openings and cornices with strongly protruding gargoyles in the form of torsos and animal heads. The impressive crowning cornice was topped with an openwork stone balustrade with slender pinnacles placed on the bends of the octagon. St. Jadwiga’s Tower, standing next to the gate leading to the city, received a cylindrical superstructure with a typically French parapet set on strongly protruding two-stage stone consoles. In the middle of the platform created at the level of this storey, a narrower angular superstructure with a polygonal spire was erected. The room located on the storey under the battlement was equipped with large windows with ashlar frames, a fireplace and a rib vault. The walls and vault of this room were decorated at the end of the Middle Ages with polychromes with a motif of a complicated plant twig, in which the figures of knights with inscriptions on banderole were embedded.

In the second half of the 15th century, the Prince of Brzeg, Frederick I, rebuilt the palatium, which lost its original division into two low storeys and a high upper floor, replaced by three floors of almost equal height. The late Gothic lowest storey had the height of the former ground floor and the first floor, the second one was at the level of the former princely floor, while the third late Gothic floor was built on in its entirety. Above it, there was probably still a low storey of half-timbered construction. In the ground floor, which retained its economic purpose, a massive barrel vault was installed. The second and third floors acquired a symmetrical plan with a large representative hall in the middle and two residential spaces on the sides, consisting of a vestibule and two rooms each. The central hall was covered with rib vault, supported by three polygonal stone pillars in the axis of the chamber. It could only be entered from the side vestibules, which were accessed from the courtyard through pointed arch portals with tracery decorating the transoms above the doors. The upper central hall was covered with a wooden ceiling and equipped with large pointed arch niches with stone seats on the sides. The lighting of the smaller interiors was provided by pointed windows, externally in stone frames with curtain arch decoration. In addition, the facades were diversified by the bay windows of the palace, which was covered with a steeper roof. In one of the vestibules there was a spiral staircase leading to the lowest floor, but vertical communication was primarily provided by external wooden porches from the courtyard side.

In the 15th century, the castle was already protected by a brick defensive wall along its entire perimeter, connected to the city defensive walls from the east and west. The external defense zone was a watered moat, also integrated with the city moat. The entrance from the city side led from the west, through the gate near the tower of St. Jadwiga, while from the outside, bypassing the city, the road to the castle led from the north, through the gate at the Lubińska Tower. This second gate was reinforced at the end of the Middle Ages with a polygonal bastion, or a type of foregate with an elongated shape and thick and low walls, equipped with embrasures for firearms.

Current state

The medieval Legnica Castle was unmatched in Silesia in terms of its ideological, artistic and architectural programme. Its founder, Prince Henry the Bearded, referred to the court architecture of the first Piasts, but also to the imperial palases of the Hohenstaufen dynasty. From this buildings only the towers of St. Peter and St. Jadwiga have survived to the present day, both with Gothic upper parts. Also the block of the palace has survived (former Romanesque palatium), with visible peripheral walls up to 12 metres high and remains of old window and entrance openings. Only relics uncovered during conservation work remained from the Romanesque chapel and the Lubińska Tower was completely demolished after the fire in 1711. Recently, the Legnica Castle has undergone revitalisation. It is accessible to tourists, but it is visited only to a limited extent due to the educational institutions located in historic buildings.

bibliography:

Chorowska M., Rezydencje średniowieczne na Śląsku, Wrocław 2003.

Grzybkowski A., Średniowieczne kaplice zamkowe Piastów Śląskich, Warszawa 1990.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Przyłęcki M., Budowle i zespoły obronne na Śląsku, Warszawa 1998.

Rozpędowski J., Różycka E., Zamek legnicki, Wrocław 1968.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.

Świechowski Z., Sztuka romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 1990.

Wagner A., Murowane budowle obronne w Polsce X – XVII wieku, tom 1, Warszawa 2019.