History

The first Slavic settlements in the vicinity of Kruszwica were established as early as the 8th-9th century. In the second half of the 10th century, a significant stronghold was established, situated on an island in the middle of Lake Gopło, with its marshy surroundings serving as a considerable barrier to overcome. Thanks to this, it could control one of the few crossings and the water and land routes running through there. The stronghold’s importance increased in the 11th century, when, in addition to its military function, it also began to play an administrative, residential and political role. At that time, it was one of the seats of the Piast rulers, which was also a convenient base for further penetration of Pomerania and Mazovia. This period ended with the destruction of the stronghold and the depopulation of the surrounding lands in 1096, during internal dynastic struggles. A bloody battle was to be fought at Gopło between the army of Prince Władysław Herman and his son Zbigniew, who rebelled against him, and who was supported by the inhabitants of Kruszwica.

A new stage in the functioning of Kruszwica took place in the 12th century and in the first half of the 13th century, when an unfortified early urban settlement with a significant craft and trade function developed on its territory. Its importance was confirmed by the construction of a stone church of St. Peter on the eastern shore of the lake and the establishment of a bishopric for a short time. In the second half of the 13th century, a smaller stronghold was built in the northern part of the former stronghold, perhaps with a chapel and a stone, cylindrical tower. It functioned as the center of the castellany, that is a mid-level administrative unit. In 1268, this stronghold (“castrum Cruszuiciense”), together with most of the castellany, passed to the Prince of Wielkopolska, Bolesław the Pious, and was burned by him in 1271, again during internal dynastic struggles. Around 1282, the Kruszwica castellany became the property of Prince Władysław the Elbow-high. The stronghold, or wooden castle, was reconstructed, as it was documented in sources in 1331 (“nobile castrum”), and in addition, the settlement on the western bank of Gopło was raised to the rank of a town. However, in 1332 Kruszwica was lost during the Polish-Teutonic War, when it was surrendered without a fight to the Teutonic Knights by the castellan Przezdrzew from the Leszczyc family. This began the Teutonic occupation of Kujawy Brzeskie region with Kruszwica, which lasted until 1337.

The entire Kujawy land was recaptured by King Kazimierz the Great in 1343. It was only after this date that the idea of building a brick castle could have been born, protecting Kujawy from the Teutonic Order and controlling an important trade route. The chronicler Janko of Czarnków reported that the castle was built on the initiative of Kazimierz the Great in the years 1350-1355. This monarch often stayed in Kruszwica, which was recorded in documents issued there in the years 1358, 1359, 1365, 1368. At that time, the castellan of Kruszwica was a trusted official of the king – Dobiesław from the Kościół of the Ogończyk coat of arms, and the function of burgrave was performed by a certain Jan. In the second half of the 14th century, the office of the starost of Kruszwica also appeared in documents. The first known one was Pietrasz Małocha from Małachów in 1377. The seat of judicial authorities and the archive were also located in the castle. The office of a judge was recorded in Kruszwica since 1242 (at that time it was certain Ubisław), which was confirmed by a document of the Płock church hierarchs, issued by Pope Gregory IX.

In 1382, a civil war broke out in Wielkopolska between the Grzymalit and Nałęcz families. The Kruszwica was captured by the supporters of Queen Jadwiga of Anjou and Prince Siemowit IV of Masovia, a pretender to the Polish crown. In 1383, Kruszwica Castle, one of the strongest strongholds in the kingdom, was captured without a fight, as a result of the surrender of the Kruszwica castellan to the army of Siemowit IV. Kujawy was seized by the Masovians, and the castle was taken by robber knights, who were venturing to the Wielkopolska-Kujawy border. Operating from Kruszwica, Michał of Kurów plundered the town of Kwieciszewo, the knight Sławiec invaded and robbed villages of the Gniezno archbishopric, and Abraham, the voivode of Płock and then starost of Kruszwica, transported numerous properties seized from Wielkopolska to the castle. During the fights, the Prince of Mazovia pledged Kruszwica to Wisław Czambor of the Rogala family, a known adventurer. His activities led to an unsuccessful attempt to capture the castle by Polish knights in 1391. The situation stabilized and the Kujawy with Kruszwica were incorporated into the Kingdom of Poland only in 1397, thanks to the efforts of King Władysław Jagiełło.

During the reign of Władysław Jagiełło, the castle as a royal residence may have lost some of its importance, because the monarch stayed in Kruszwica only twice, always during his journey from Kujawy to Wielkopolska, more often choosing Brześć Kujawski, Inowrocław or Radziejów. Jagiełło’s son, King Kazimierz IV Jagiellon, stayed in Kruszwica only once. Throughout the 15th century, the castle functioned as the seat of state offices, primarily the starost, who performed administrative and judicial functions on behalf of the king. It also served as a prison, as evidenced by the events of 1409, when Bernard, the former starost of Bydgoszcz, was imprisoned in the castle, accused of handing over the Bydgoszcz castle to the Teutonic Knights in exchange for a bribe. Kruszwica’s military role clearly decreased in the second half of the century, with the defeat of the Teutonic Order as a result of the Thirteen Years’ War. During the war, the castle avoided major damages.

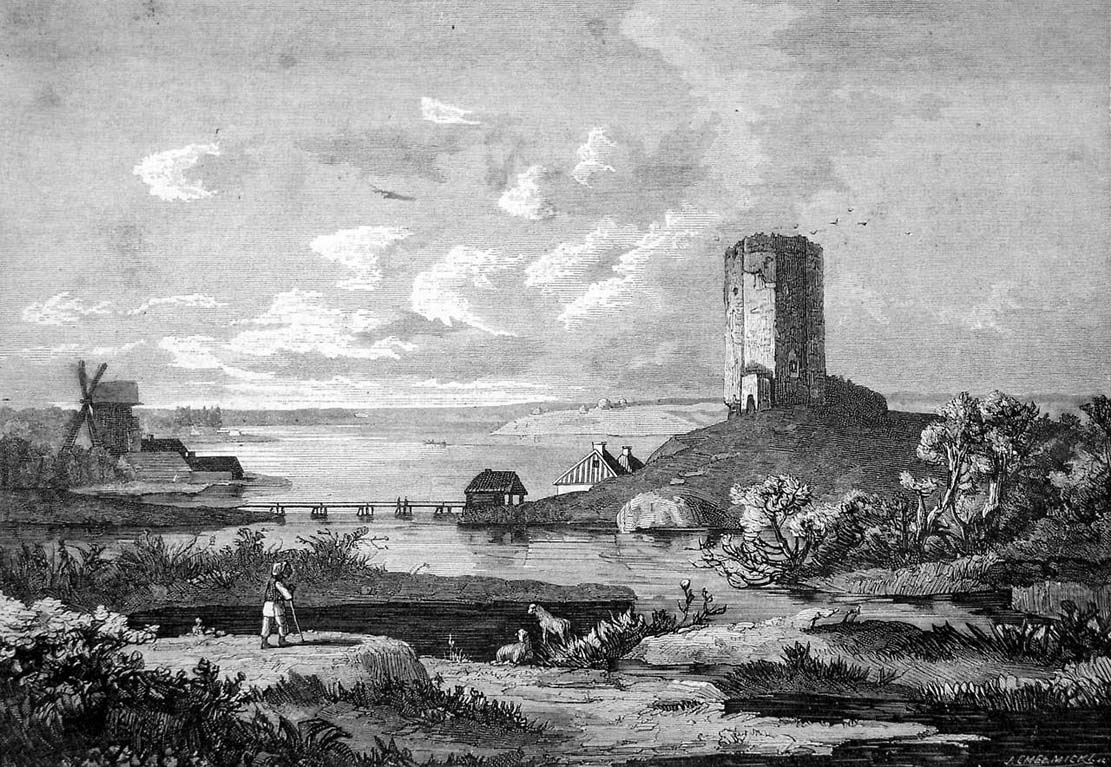

In the 16th century, Kruszwica Castle was destroyed by fire twice. The first time was in 1519, and then around 1588, during the castellany of Wojciech Niemojewski of the Szeliga coat of arms. After the latter, the castle was rebuilt around 1591, which was commemorated by a date engraved on the wall of the basement of one of the buildings. Renovation works and transformations introduced by the starosts residing in the castle led to a partial early modern change in the appearance of the castle. Moreover, when Kruszwica was occupied by the Swedes in 1655, they surrounded the castle with bastion fortifications. This began a two-year occupation, at the end of which the Swedes burned the castle on the order of General Jacob de la Gardie. In the survey of the Kruszwica starosty from 1659, it was recorded that the castle was ruined and the archive burned. No attempt was made to rebuild it, and in the 18th century the abandoned walls were gradually dismantled by the local population and tenants. Thorough demolition work was carried out after 1787 on the orders of the Prussian authorities. Only thanks to the efforts of Jan Mittelstaedt of Kołuda and his intervention with the Prussian King Frederick William IV, the slightening of the main tower and its adjacent curtains was stopped.

Architecture

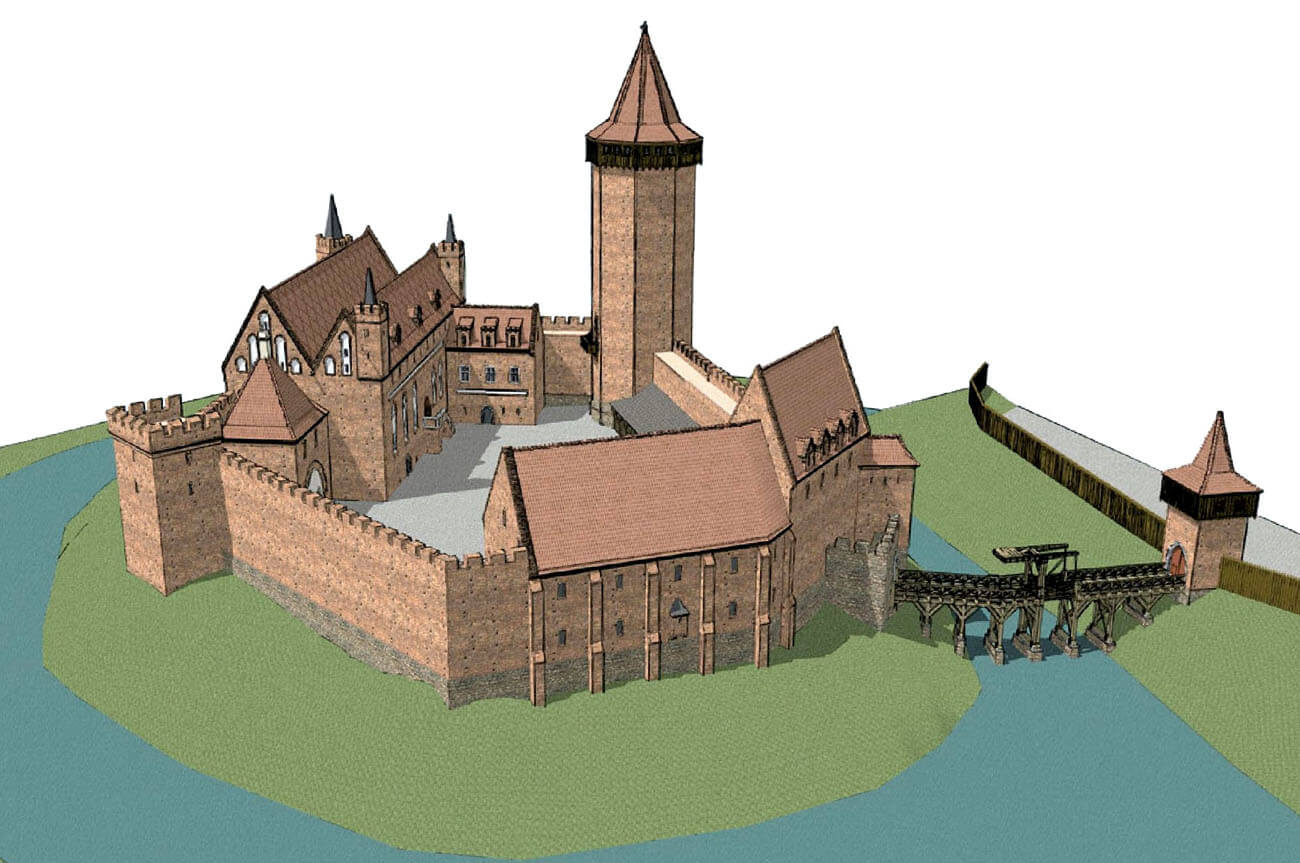

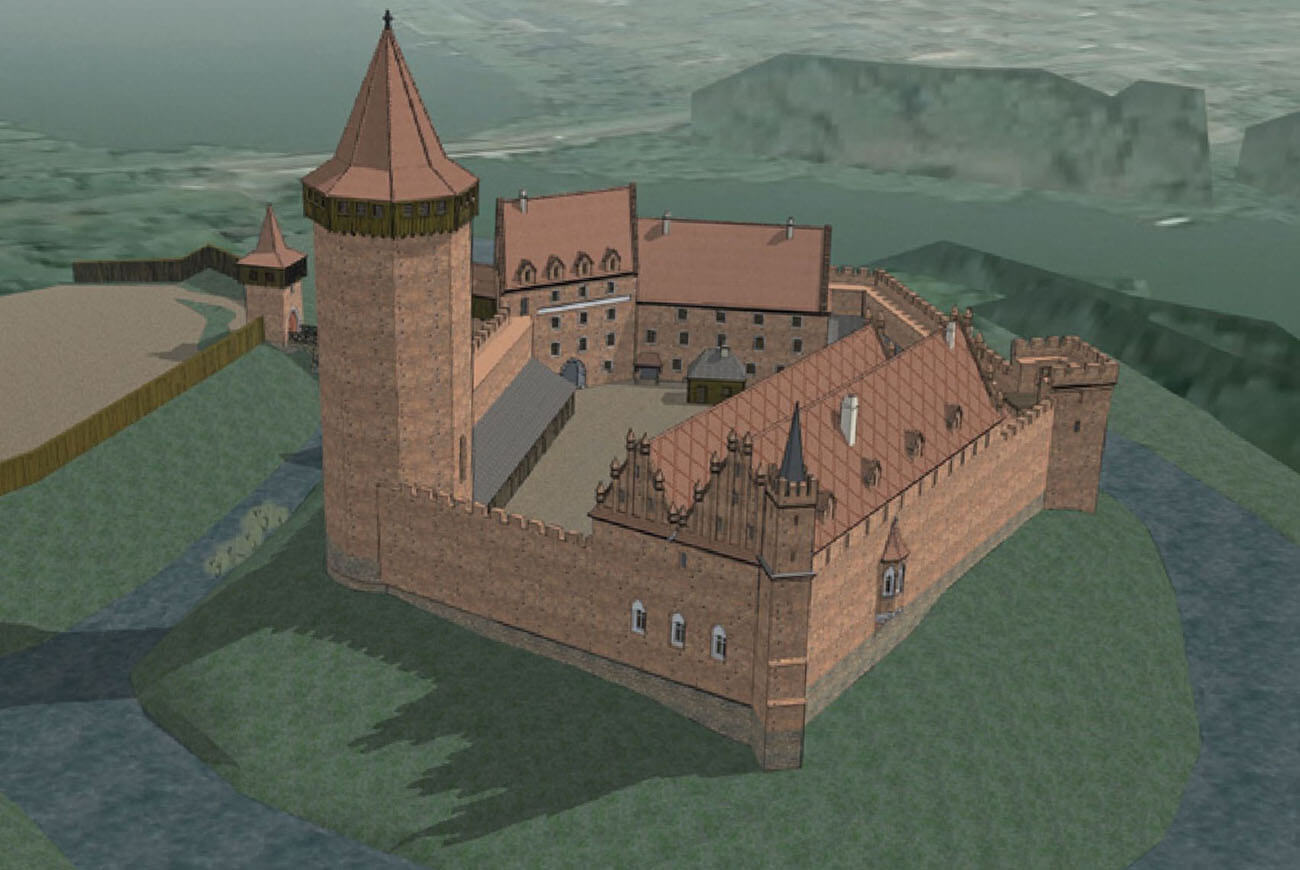

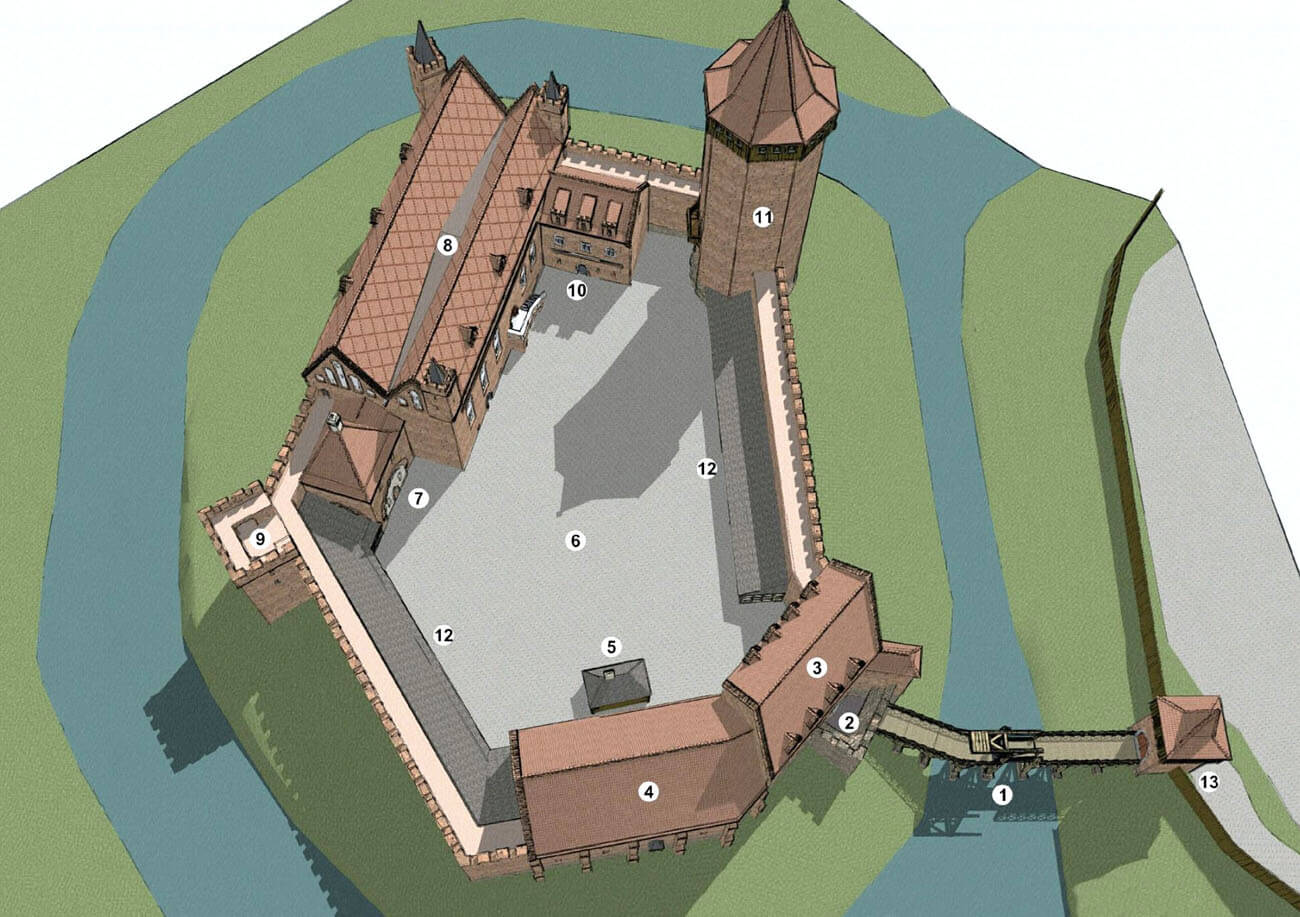

The brick castle was built on an island above the waters of Lake Gopło, in the southern part of the former stronghold, thanks to which it stood on a small elevation, from which it could control the vast, flat and marshy area. After leveling, before starting to erect the brick buildings, the castle area was additionally raised by about 4 meters with an earth. A canal was dug around it, acting as an irrigated moat, separating the castle from the outer bailey. The core of the castle consisted of a polygonal perimeter of defensive walls separating an internal courtyard measuring 62 x 57 meters. In their western corner, a massive tower with the function of a bergfried was located. Another tower, much smaller, quadrangular, perhaps opened from the courtyard side, could have been located in the south-eastern part, where it was strongly protruding in front of the neighboring curtains. The residential and utility buildings were erected at southern and eastern parts. The entrance with the gatehouse and later foregate was located on the north-eastern side. It was preceded by a drawbridge leading to the outer bailey.

The castle walls were built of hand-formed bricks, on a stone base made of partially worked glacial erratics. The brick part was created with a Flemish bond, bonded with sand-lime mortar. The core filling of the wall consisted of erratic boulders, rubble and bricks. The thickness of the curtains at the ground level reached 2.7-3.2 meters, the height reached 10.7 meters, and the crowning had the form of a crenellated parapet protecting the defenders’ wall-walk. Due to the considerable thickness of the curtains, this wakk-walk did not require widening with a wooden porch. The protecting it parapet provided an additional height of at least 1.5 meters. The wall was reinforced by two massive buttresses: in the south-west corner by the main building and in front of the north-east corner of the gatehouse. Both were probably topped with turrets, perhaps housing staircases.

The main castle gate was built in two stages. Initially, it was probably an ordinary opening in a protruding section of the defensive wall. It was flanked by a massive buttress mentioned above (probably topped with a turret or defensive porch), protruding towards the north-west. In the next, still medieval stage, the space between the buttress and the defensive wall was closed in the form of a probably unroofed foregate. Behind it, a two-story gatehouse was located, covered with a gable roof with four dormers. Its gateway could be secured by a portcullis and doors, the latter of which in the Middle Ages most often rotated on vertical beams (poles) set in sockets carved in stone or carved in wood. The gates were probably blocked with a bar. In front of the gate, the road led over a wooden drawbridge, connecting with the outer bailey. On its premises, the entrance to the bridge was secured by a quadrangular tower and a palisade.

The massive main tower in the western corner was built on an octagonal plan, 32 meters high and with an external diameter of 13 meters. It served as a bergfried, and therefore a place of final defense. In addition, it could serve as a prison and a place to store military equipment or supplies on a daily basis. It was topped with a wooden superstructure with a high pyramidal roof, perhaps in the form of a hoarding. The external elevations of the tower were separated by numerous putlog holes, left from the scaffolding used during construction. The tower had no windows or arrowslits, the defensive and observation storey was created only by the aforementioned wooden superstructure.

The lowest storey of the tower housed a cell in the form of a circular room with a diameter of only 3 meters, with walls made of stone. It was probably a relic of an older, cylindrical tower from the 13th century, brick-lined and raised in the 14th century. At that time, the cell was also covered with an octagonal and pointed brick vault, in which a communication opening was left in the middle. The entrance to the tower was placed on the second floor level. It led to a vestibule with two simple brick portals with pointed arches. Both were closed by bars from the vestibule side, using horizontal beams placed in the wall. The external recess would indicate the possibility of a drawbridge to the tower. The vestibule led to the guard’s room, placed on the vault above the cell. The guards’ room was probably heated by a fireplace. The upper floors of the tower were separated by wooden, flat ceilings with beams set in sockets in the wall. The last, eighth floor must have been connected to the hoarding porch.

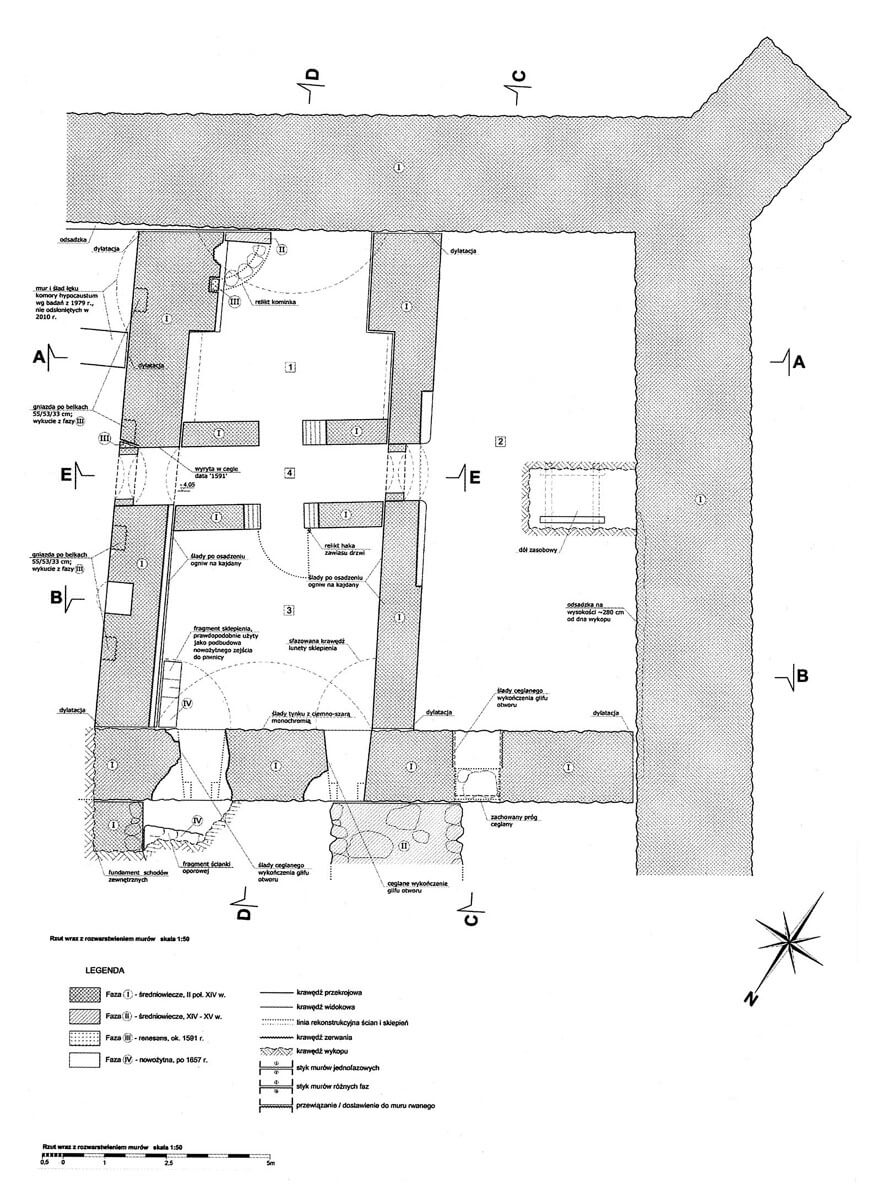

The main residential and representative house measuring 16 x 39 meters was built in the southern part of the courtyard. Like the other buildings, its walls were added to the perimeter wall without cutting a groove or leaving any visible toothing. It had a two-line division, a double gable roof supported by pairs of triangular gables, a quadrangular turret on a buttress, and two turrets flanking the front (northern) elevation. The thick defensive wall probably made it possible to walk around the building using the porch in the crown. The house had two floors, a ground floor and basements. The main entrance was located in the middle of the elevation from the courtyard side. It probably led via brick external stairs, to the court rooms, the archive, and then to the royal chambers.

Probably at the end of the 14th century or at the beginning of the 15th century, the building was enlarged by a smaller and lower two-storey western wing with internal dimensions of about 13 x 10 meters, which involved the necessity of bricking up one of the windows in the northern wall of the basement. In order to illuminate the added wing, windows were also made in the peripheral western wall. The new wing had no basement and its stone foundations did not differ from the older structure. It did not reach the main tower, leaving a part of free curtain on the side of the courtyard. On the east side, the main building was adjoined by a kitchen – a small, rectangular building covered with a hip roof with a centrally positioned bottle chimney, under which there was probably a pedestal for the hearth. Near it, or perhaps inside, there must have been a well.

The basements of the main building were barrel vaulted. Their single-chamber southern part served as storage, as a pit lined with planks was found there. The second part was divided into three rooms by a narrow passage, 5.3 meters long and 1.5 meters wide. The southern section was occupied by a guard’s room heated by a corner fireplace. The northern section served as a prison cell, as evidenced by traces of shackle links right by the floor. Light was provided there only by two small openings, one of which was covered by the western wing. In the southern corner there was a small space, dedicated for a hypocaust furnace, which accumulated heat through hot stones placed above the grate. From there, channels distributed heat to individual rooms of the building, where it was released through green-glazed holes in the floors.

The rooms on the ground floor and upper floors were covered with wooden ceilings supported by pillars or columns. On the ground floor there was a representative entrance hall with a single flight of stairs along the external curtain wall. Stairs led to the upper level of the ground floor in the western part. In addition, the ground floor was also connected to the kitchen in the east. On the first floor there were residential and representative chambers, equipped with numerous architectural details (e.g. a pointed, richly moulded sandstone portal). Customarily, the queen’s rooms were located on the left side of the entrance, and the king’s rooms on the right, although the functional purpose of individual rooms could have been changed by starosts and tenants. In the central part there could have been a court chamber, lit by three stone, four-light windows, probably also serving as a representative hall. On the axis of the external southern wall, partly in the thickness of the wall and partly in the form of a bay window, there could have been a castle chapel, probably dedicated to St. Vitus. The last, probably lower floor housed servants’ quarters and provided additional living space. Under the high roofs there could have been storage rooms and warehouses.

The eastern building of the castle was a structure with basement and two above-ground storeys, covered with a gable roof. Its external elevation was reinforced with several characteristic buttresses reaching the crown of the wall. Due to its location near the corner of the courtyard, the northern bay of the building was probably curved and connected to the gatehouse. In front of the eastern building in the courtyard stood a wooden bath with a stove. Between the main tower and the gatehouse there was a long and narrow utility building with a mono-pitched roof, adjacent to the defensive wall. It had a wooden or half-timbered structure. Its ridge height reached about 10 meters. A similar structure probably also existed between the kitchen and the eastern building. There could have been stables, granaries, storerooms and other rooms necessary for the everyday functioning of the castle’s inhabitants.

Current state

The castle hill has a form obtained today as a result of 18th-century demolition works and the leveling of the land in 1867. To this day, all that remains of the castle is the so-called Mouse Tower and fragments of the defensive wall that joined it on two sides (the name of the tower refers to the well-known legend of King Popiel eaten by mice, written down in the 1120s by an anonymous chronicler called Gallus, and associated with Kruszwica only at the end of the 13th century). Currently, the tower is a tourist attraction in Kruszwica and a viewpoint. Recently, a wooden bridge leading to the castle was built, and work is also underway to make the basements of the southern wing accessible.

bibliography:

Dzieduszycki W., Maciejewski M., Małachowicz M., Zamek Kruszwicki, Kruszwica 2014.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Pietrzak J., Zamki i dwory obronne w dobrach państwowych prowincji wielkopolskiej, Łódź 2003.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 2, architektura obronna, Kalisz 2011.

Zamek kazimierzowski w Kruszwicy. Najnowsze badania, red. J.Sawicka, W.Dzieduszycki, Poznań-Kruszwica 2024.