History

Officially, the Franciscans settled in Krosno in 1378 by the decision of the bishop of Przemyśl, Erik, but they had to act in the town much earlier, certainly before establishing a parish, which would be indicated by a dispute between the Krosno parish priest, Klemens, and the Franciscans, on the performance of their parish functions. The beginnings of the parish were connected with the incorporation of Krosno to the Polish kingdom by Casimir the Great in 1340 and the foundation of the town, so the monks had to come to Krosno in the first half of the 14th century or perhaps even in the 13th century, as part of a colonization and missionary campaign.

In 1397, Queen Jadwiga approved the granting of land to the Krosno friary, and canceled the patronage of the town council over the church and the Franciscan friary. It also forbade the mayor and councilors to interfere in the affairs of the friary under the threat of a severe financial penalty, and this was confirmed by King Władysław Jagiełło who stayed in Krosno in 1407. These steps were caused by the fact that the town authorities made claims to the management and care of the church, friary, its furnishings and property. The most sensitive issue was the inspection of liturgical and decorative vessels in the church equipment, which came from the donations and gifts of the inhabitants of Krosno. The patronage of the town council was also the result of the tradition according to which the Franciscans, after arriving in Krosno, were to settle at the town chapel.

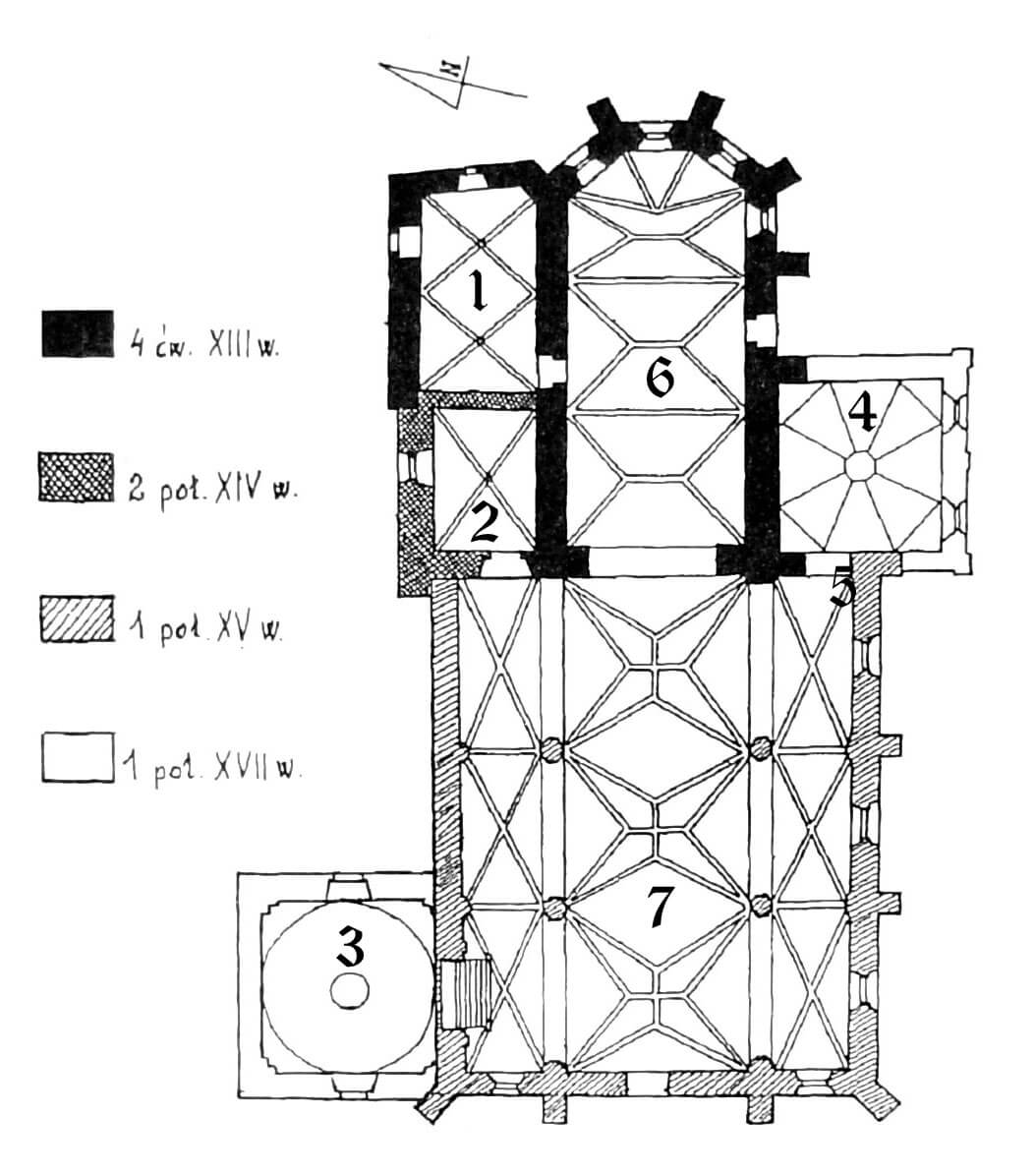

The fire of Krosno in 1399, contrary to previous assumptions, probably did not severely devastate the friary, because a year later the Franciscans, with the permission of King Władysław Jagiełło and the staroste of Sanok Ścibor, purchased a town plot for 300 fines of Prague groschen, and in 1402 they could afford an additional donation of 100 fines, in order to fortify the south-eastern part of the town. It is unlikely that it was only then that the brothers moved from the right to the left bank of the Wisłok River, where they were to start building a new church, but they most likely operated within the charter town from the very beginning and used the purchased plot to expand the church and monastery. It was then that they added an aisled nave to the older chancel with a sacristy. The decoration and furnishing of the friary church continued until the beginning of the 16th century. In 1510 in Rome, the Czech-Polish provincial, Walenty of Krosno, obtained indulgences for the donors, as a result of which the church was equipped with 11 altars, stalls, paintings and sculptures.

The Franciscan friary in Krosno was not only of local importance. It was also a support for the missionary action in Rus. This role appeared especially after the union of Poland with Lithuania in 1386, when huge Ruthenian-Lithuanian territories were opened for missionary work. The second important role of the friary was its defensive function, caused by being included in the town fortifications. In the event of an invasion, the friary undertook to man the nearby tower with its own crew and, for this purpose, always have armaments prepared, which was indeed often recorded by the inventories. The defense system passed the test in 1657 during the siege of Krosno by the army of the Transylvanian prince George II Rákóczi.

In 1591, the voivode of Sandomierz, Jerzy Mniszech founded new, brick friary buildings. In 1615, the early modern chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary was erected in the corner between the chancel and the southern aisle of the church, and in 1647 Stanisław Oświęcim, a courtier of King Władysław IV, added the Oświęcims Chapel. Despite these foundations, the Protestant Reformation brought stagnation, and even a serious regression, in the activities of the Franciscan friary. Public processions disappeared, the brotherhood of the Blessed Virgin Mary ceased to exist, the number of calls to the novitiate decisively decreased, as a result of which in 1581 the number of monks in the Krosno friary dropped to two. The situation began to improve at the beginning of the 17th century after the introduction of the first reforms of religious education and the creation of the cult of the image of Our Lady of Murkowa.

In the 18th century, wars, natural disasters, plague and economic crisis resulted in impoverishment, depopulation and the decline of the town and, consequently, the friary. During the Northern War, the Swedes plundered the church, and poverty prevailed in the depopulated community. In 1717, part of the friary was ruined. Renovations could only be carried out in 1731, thanks to a donation from the landowner Antoni Baranowski. The friary survived in this state until the dissolution of the friary imposed by Emperor Joseph II in 1782. It is true that at the beginning of the 19th century a part of the church was allocated to grain storage, but thanks to the efforts of the townspeople and monks, the community was allowed to return to the friary.

In 1872, as a result of a fire, almost all the interior of the church burnt. Its consequence was also the collapse of the Gothic vault of the chancel and the destruction of the roof structure. The renovation of the building was carried out in the years 1899-1904, which was combined with the regothisation of the church, by removing most of its elements from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Architecture

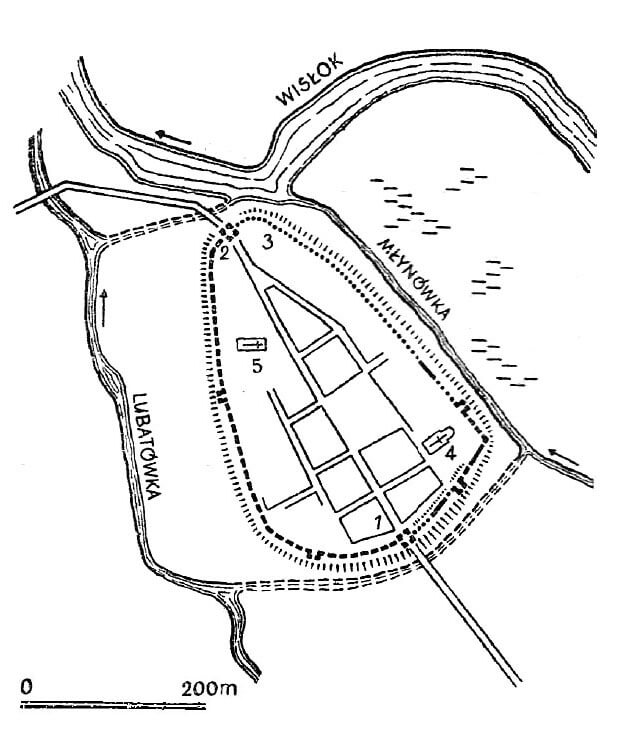

The Franciscan friary at the beginning of the 15th century was located in the south-eastern part of the town, in the corner of the defensive wall built by King Casimir the Great, between the lower tower on one side and the higher tower on the other, near the Hungarian Gate. A narrow street led from it to the Franciscan walls. Wąska Street, also known as Do Franciszkanów, led from the market square to the church. The town council operated in the tenement house at the corner of Franciszkańska Street and the market square, while the almshouse was located on Franciszkańska Street.

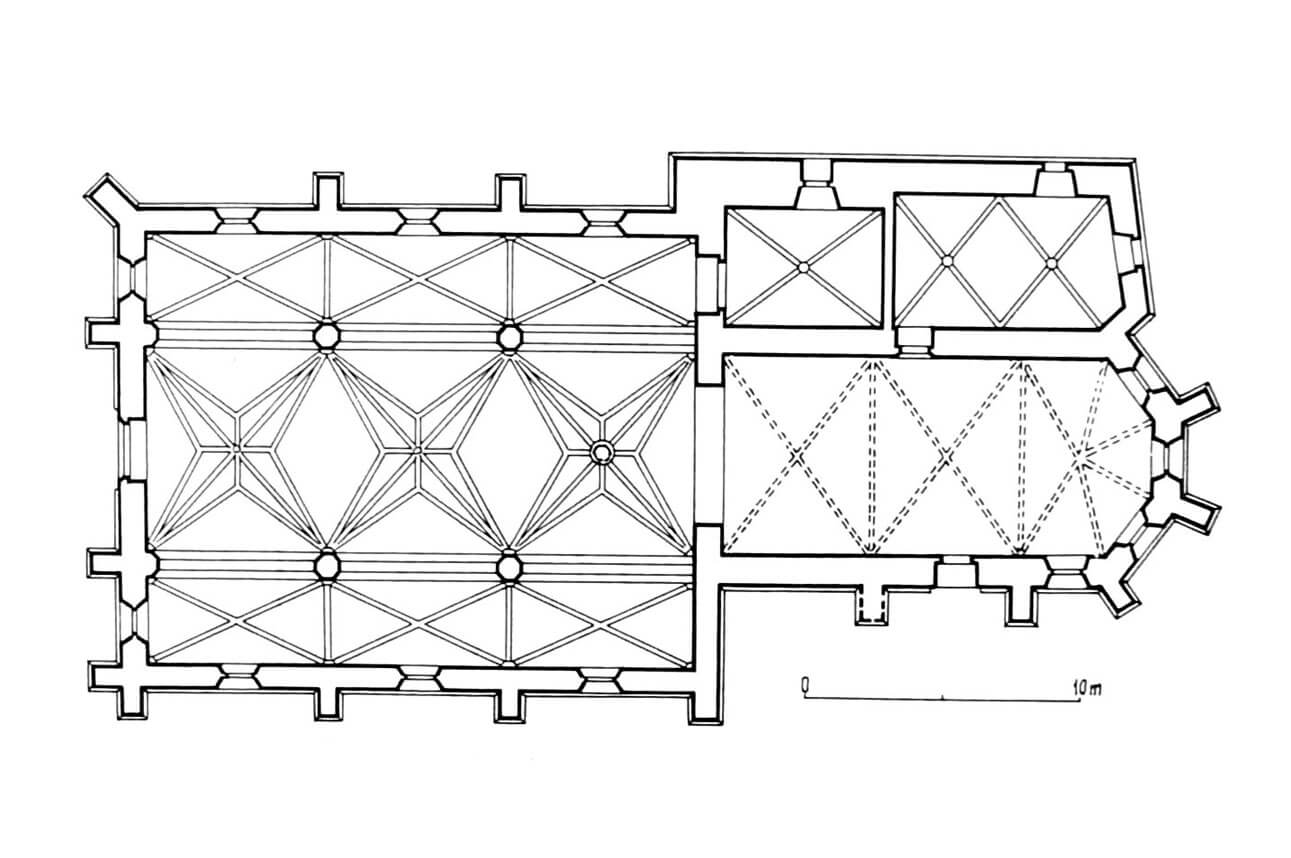

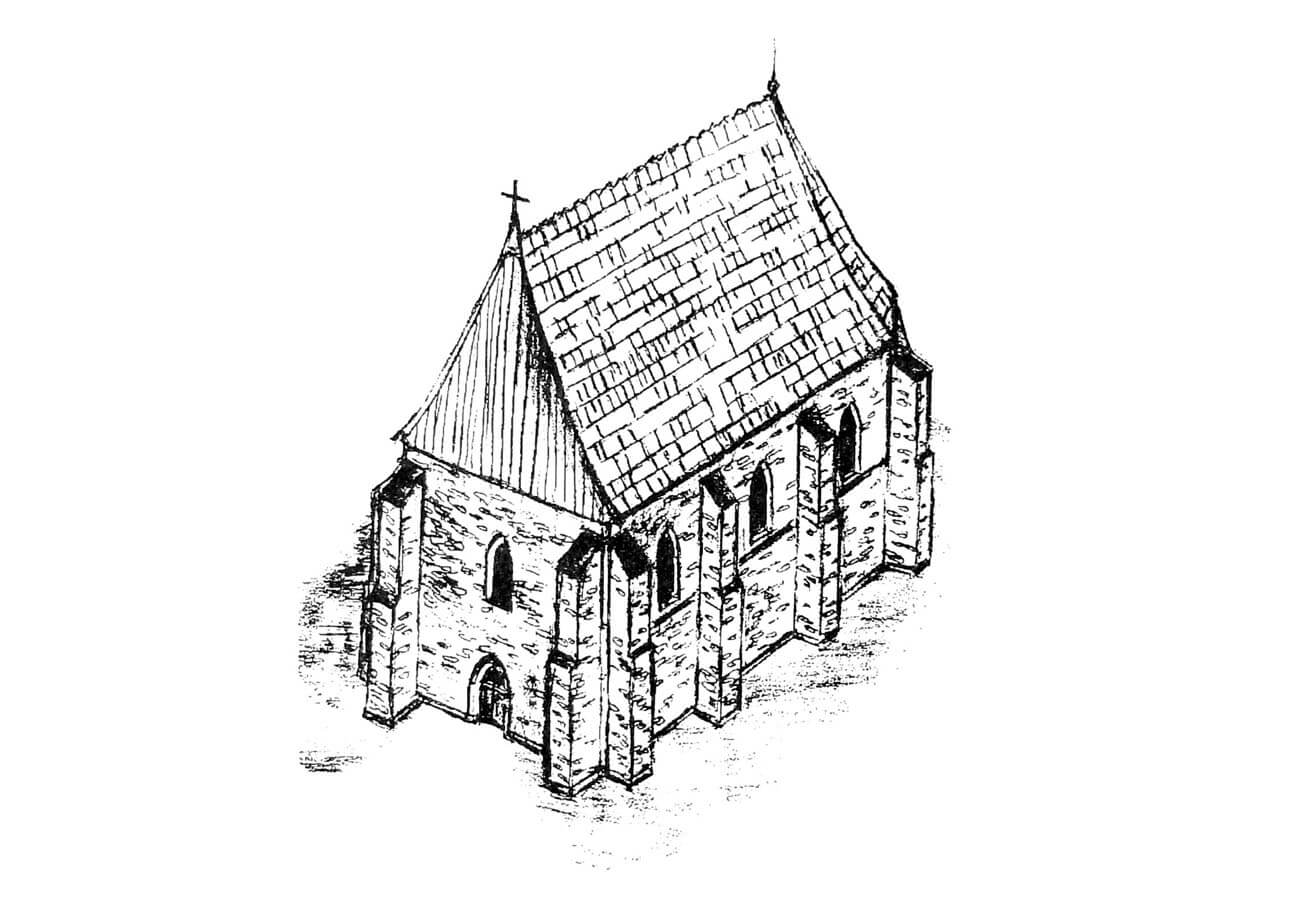

The friary church from the beginning of the 15th century was an orientated building, with central nave and two aisles of a three-bay pseudo-basilica arrangement (the central nave higher than the aisles, but without its own windows), with a chancel slightly narrower than the central nave, three-bay, polygonal ended in the east. The chancel and the sacristy located on its northern side were the earliest church from the 13th or 14th century, originally built of sandstone, enlarged in the second half of the 14th century by the chapel of the Transfiguration at the western wall of the sacristy. As a small aisleless building measuring 7.3 x 16.7 meters, with walls up to 1.5-1.6 meters thick on the ground floor, the original church functioned until the nave was built. During the expansion, the walls of the chancel were raised by 4 meters, to 12 meters high, using bricks laid in a Flemish bond, so that about 2/3 of the height was now sandstone, and the rest was a thinner brick wall with a decorative zendrówka pattern.

When nave was added, advanced construction works had to be carried out, because the chancel was built on a lower ground level than the rest of the church (this is evidenced by the plinth running around the chancel and aisles). A shaft was made in the chancel and the floor was raised to the level of the central nave floor, probably also the vault in the chancel was raised. The nave had walls 1.2-1.3 meters thick, inside covered with a vault supported by four stone, octagonal pillars between the aisles and three pairs of half-pillars (from the east, west and north). The sculptor’s chisel did not make any rich decorations on the stone bosses of the stellar vault of the central nave. The brick ribs were springing from the pyramidal corbels with six-sided bases. A cross-rib vault was installed in the aisles, sacristy and northern chapel. The vault above the chancel was probably cross-rib, based on stone corbels suspended at a height of about 9.3 meters. The stone ribs were fastened with bosses, which had rich architectural details in the form of shields and plant rosettes carved in sandstone.

The entrance to the church was formed by a pointed and moulded portal placed on the axis from the west. Above it there was a cornice, and higher there was a tall, three-light, pointed-arch window, splayed on both sides, flanked by slightly smaller two-light windows in the aisles. The whole was topped with a triangular gable, filled with pyramidally arranged blendes, of which the two middle ones were of the same height. There were probably brick or stone pinnacles springing from the gable steps. The under-window cornice also ran around the side walls of the aisles, and was also run along the buttresses surrounding the nave from the west and south. The older chancel was reinforced with stepped buttresses from the east and south. They were tied to the walls, which would indicate that it was planned to install a vault inside from the very beginning.

The original friary buildings from the beginning of the 15th century, located on the south side of the church, were of wooden construction until the end of the century. In 1402, it was decided to fortify the monastery. It received stone and brick walls, over one and a half meters thick, from which a new town wall ran further in two directions. The Franciscans were also to protect the windows with iron bars both in the room (refectory) and in residential cells. They also received a permit to run a drainage channel under the new, outer line of the defensive wall.

At the end of the 16th century, in the friary building, there were two large rooms (summer and winter refectory) a kitchen, and monks’ living quarters on the first floor. The refectory was covered with a decorated larch ceiling. According to the opinion of those times, the friary looked more like a castle than a traditional monastery. It was surrounded on all sides by a wall, while on both sides the complex was surrounded by a double wall, known as the upper and lower one. From the north-east side, behind the double wall, there was a road to the mills, and behind it there was a mill-house, which brought water to them from the Wisłok. Only at a certain distance did the river flow.

Current state

The current appearance of the friary church is due to a thorough renovation and regothization at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. The eastern and southern walls of the chancel were refaced, the early modern annexes from the west and south were demolished, the original appearance of the west façade was restored, including the reconstructed gable. New window traceries were also made, while the early modern southern and northern chapels and the early modern vault in the chancel have not been demolished. The 15th century vault has been preserved in the sacristy and in the nave, the latter of which is one of the oldest preserved nave vaults in the region. The friary buildings have completely lost their original stylistic features.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Łopatkiewicz P., Średniowieczny kościół franciszkański w Krośnie, Krosno 1993.

Widawski J., Miejskie mury obronne w państwie polskim do początku XV wieku, Warszawa 1973.

Zwiercan A., O franciszkanach w Krośnie do końca XVIII wieku. W 600-lecie kanonicznej erekcji klasztoru w Krośnie, “Nasza Przeszłość”, tom 51, 1979.