History

Collegium Maius was erected as the building of the Kraków Academy, founded by King Casimir the Great in 1364. Like other medieval universities, it consisted of autonomous colleges that were the workplace of the faculties. There were didactic classes in the colleges, and scholars lived and worked in them. They also had a separate administration and judiciary, gathered professors who worked in them, but also lived, rested, and spent most of their lives. The first seat of the university is unknown, probably some of the lectures were held at the royal castle or at the school at St. Mary’s Church. The beginnings of Collegium Maius date back to 1400, when King Władysław Jagiełło, after the university was renovated, handed over to it the corner tenement house of Szczepan Pęcherz from the beginning of the 14th century (in the years 1392-1395 belonging to the Kraków merchant Petr Gerhardsdorf), purchased for valuables donated a year earlier in the will of the queen Jadwiga.

In the fourteenth century, the academy was organized on the model of a university in Bologna, where students chose the rector. Only from the fifteenth century, the Parisian model was introduced, where professors elected the rector and deans. The primary faculty was supposed to be the faculty of law, as many as 8 law departments were founded, including 3 of canon law and 5 of Roman law. In addition, faculties of liberal arts and medicine were founded, but the Pope initially refused to establish a theological faculty. It was added after the reactivation of the university in 1400. In contrast to the Italian universities, whose livelihoods were the fees of students, the king provided profits from saltworks to the professors.

In 1403, the second building of the college of the University of Kraków, Collegium Iuriducum for lawyers, was built, and in 1449 Collegium Minus, but the main university building until the end of the 18th century was Collegium Maius. The rector was in office there (if he was not a lawyer), the deans of two and then three faculties (liberal arts education and theology, later also medicine) lived and worked there, as well as university elders, and from 1501 a notary. The Collegium Maius housed a library, a treasury, an archive and a prison. There were also meetings of scholars, members of colleges and faculties (called convocations). The oldest building of the college soon became insufficient for the expanding university. In 1417, with the consent of the king, the Kraków voivode, Piotr Szafraniec, purchased from a Jew called Szmul, two further adjacent buildings along with back outbuildings, and in 1434 another house was bought at St. Anna Street, formerly owned by the Jew Isaac. The acquired tenement houses were expanded and adapted for the needs of the university, and new buildings were erected in stages on the plots in the following years.

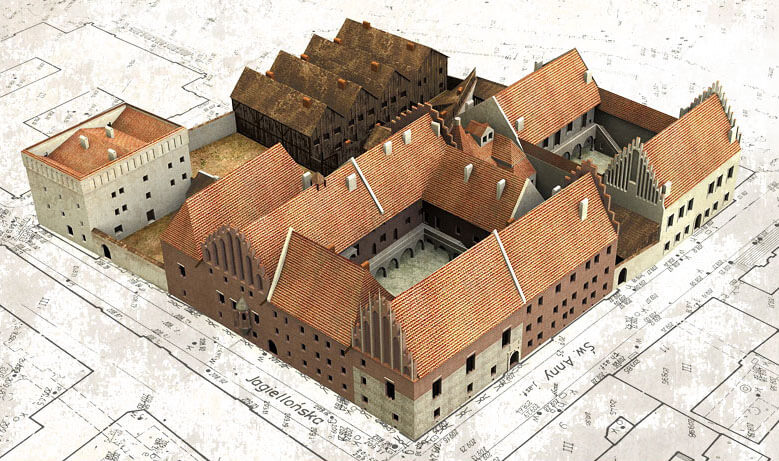

In 1462, a fire broke out in the Dominican monastery, which quickly spread to the neighboring tenement houses and the Collegium Maius. Thanks to the quick and efficient rescue of students and professors, the losses in the college were not large, and renovation began immediately. In 1469, the Długosz brothers bought a large part of the property of the Jewish community located at the back of the university buildings and handed them over to the university (later west wing of the college). Unfortunately, in 1492 another fire broke out at the Shoemaker Gate, which destroyed houses near the church of St. Anna, including the buildings of Collegium Maius, along with a new mechanical clock. The losses were large, but the decision was made to rebuild and expand the college, which was carried out thanks to financial aid, among others, by the bishop and chancellor of the Collegium Maius, Fryderyk Jagiellończyk and other state dignitaries. The university authorities were also lucky, because two years later, in the niche of Socrates’ Lecture wall, professors of theology found a treasure of 2508 zlotys, probably hidden and forgotten by the former owners of the tenement house. The money was used to erect stairs and an arcaded cloister, for the construction of which a contract was signed with the master Johan of Saxony in 1493. It is worth noting that the Collegium Maius was also shaped by the university scholars themselves, who discussed and made decisions about the vaults, the courtyard, the location of stairs and lecture rooms, as well as decorations and materials.

In 1507, an architect named Marek rebuilt the representative hall, and in 1511 the university purchased a wooden house belonging to a certain Goslar (Goldszlager) in which goldsmiths worked. The reason for the transaction was prosaic, because collegium wanted to end the noise of forging craftsmen, disturbing students and professors. Similarly, in 1580, Collegium Maius bought a nearby brewery, which was a nuisance for the university, from which the waste flowed into the courtyard of the university house, and what’s more to which the owner planned to add an upper floor, that would block the light in the lecture rooms. The final late Gothic appearance of the college was obtained a little earlier, around 1540, when the construction of the library and the professors’ garden were completed.

At the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, when the city fell into financial difficulties, Collegium Maius also ran into financial problems. In 1655 and in the years 1702-1707, Kraków experienced two Swedish invasions, but luckily for the university, they did not cause direct damages to the college buildings. Moreover, the lack of funds in the early modern period contributed to the lack of major Renaissance or Baroque transformations of the university, where work was limited to the most necessary renovations (including a massive buttress in the corner of the oldest house). They were urgent due to the foundation of the college in a wet area with numerous subterranean waters causing the walls to crack and landslides.

In the years 1777-1783 the history of the university as a community of self-governing colleges came to an end. The reforms were under the patronage of the author of changes, Hugo Kołłątaj. Ultimately, he obtained a permit from the National Education Commission to transform and extend the competences of the university, which took over the entire lower education. The reform liquidated professors’ residences in Collegium Maius, ended their collective life, moved most of the classrooms out of the building, only the library and archives were preserved there.

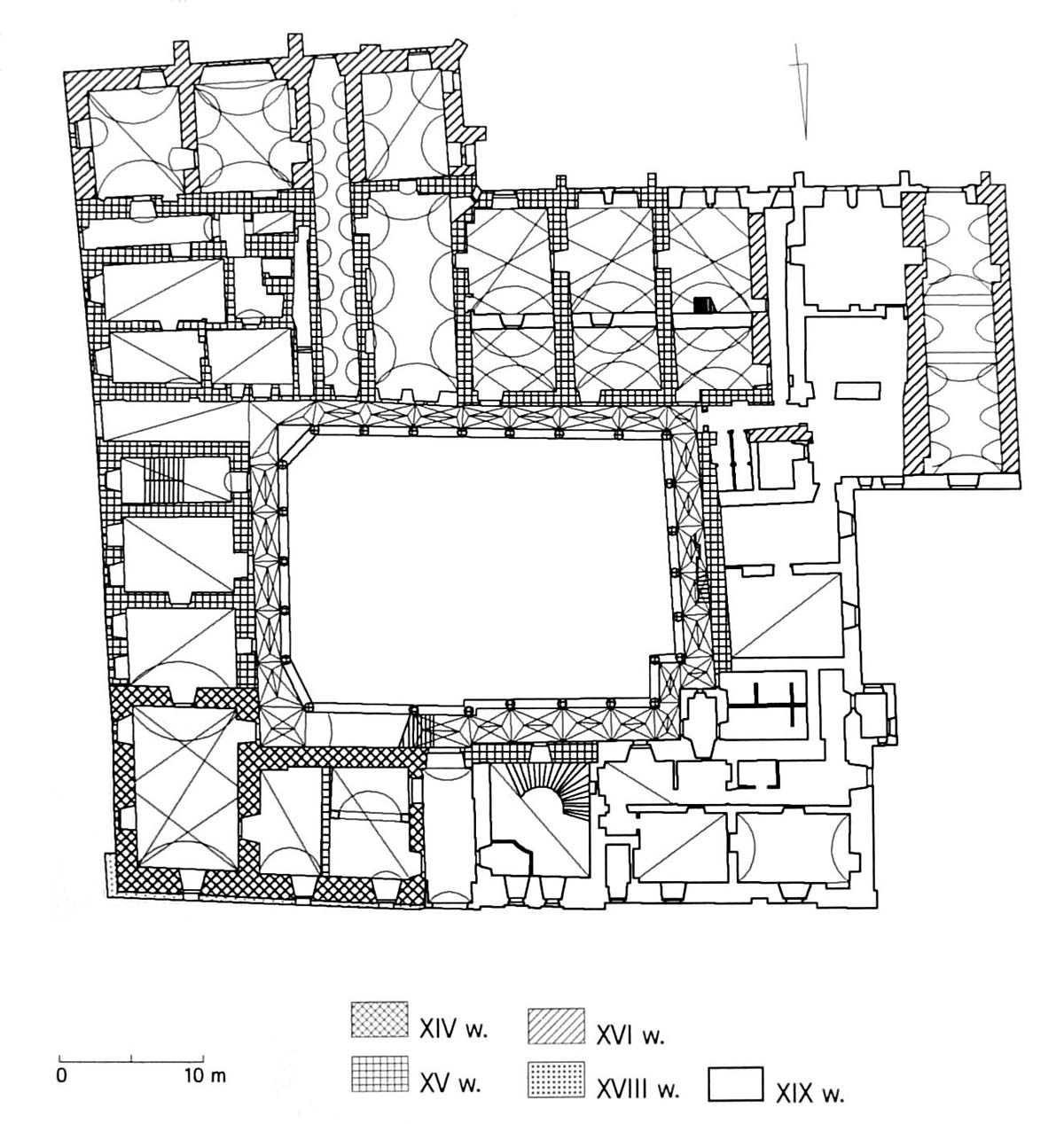

Until the mid-nineteenth century, the appearance and internal layout of Collegium Maius did not change much. It was only in the years 1840-1870 that the college was rebuilt in the neo-Gothic style in connection with the purpose of the building as the seat of the Jagiellonian Library. In the years 1949-1964, on the initiative of Professor Karol Estreicher, a comprehensive renovation of Collegium Maius was carried out, combined with the abandonment of the neo-Gothic style and restoring the original appearance.

Architecture

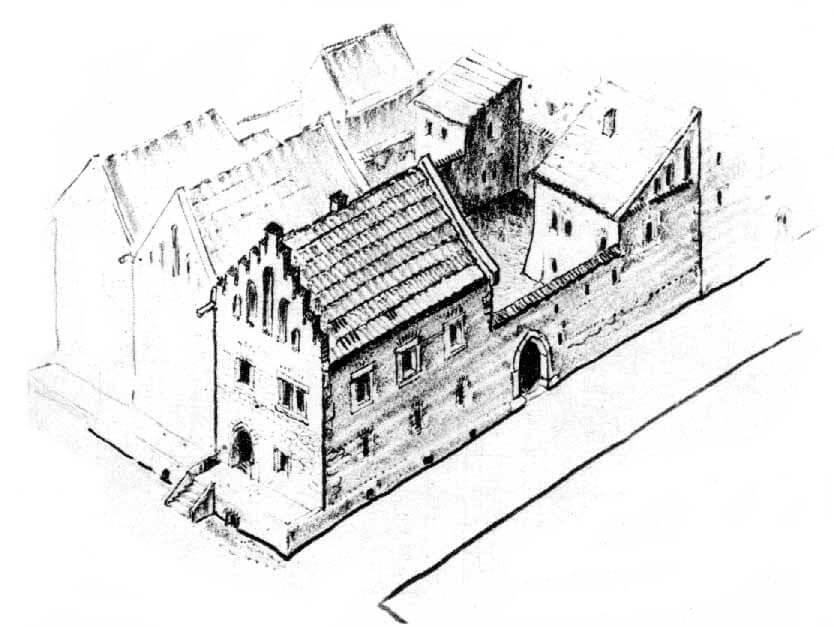

Collegium Maius was built of stones and bricks on a plan similar to a quadrilateral, created by joining a series of medieval tenement houses surrounding an internal courtyard. The oldest house of Collegium Maius was situated at the corner of Żydowska Street (St. Anna Street) and Zaułek Żydowski. It towered over the neighboring buildings, it was multi-storeyed, covered with a gable or hip roof, but not too large, about 10 x 20 meters in plan. It could have the form of a tower house. One hundred meters from the building there was a small church of St. Anna, and next to it the cemetery where university professors were later buried. Numerous wooden and brick houses were built in this place, stretching along the street to the nearby city walls. There was also a wooden synagogue near the walls, and another small cemetery outside the gate called Jew Postern.

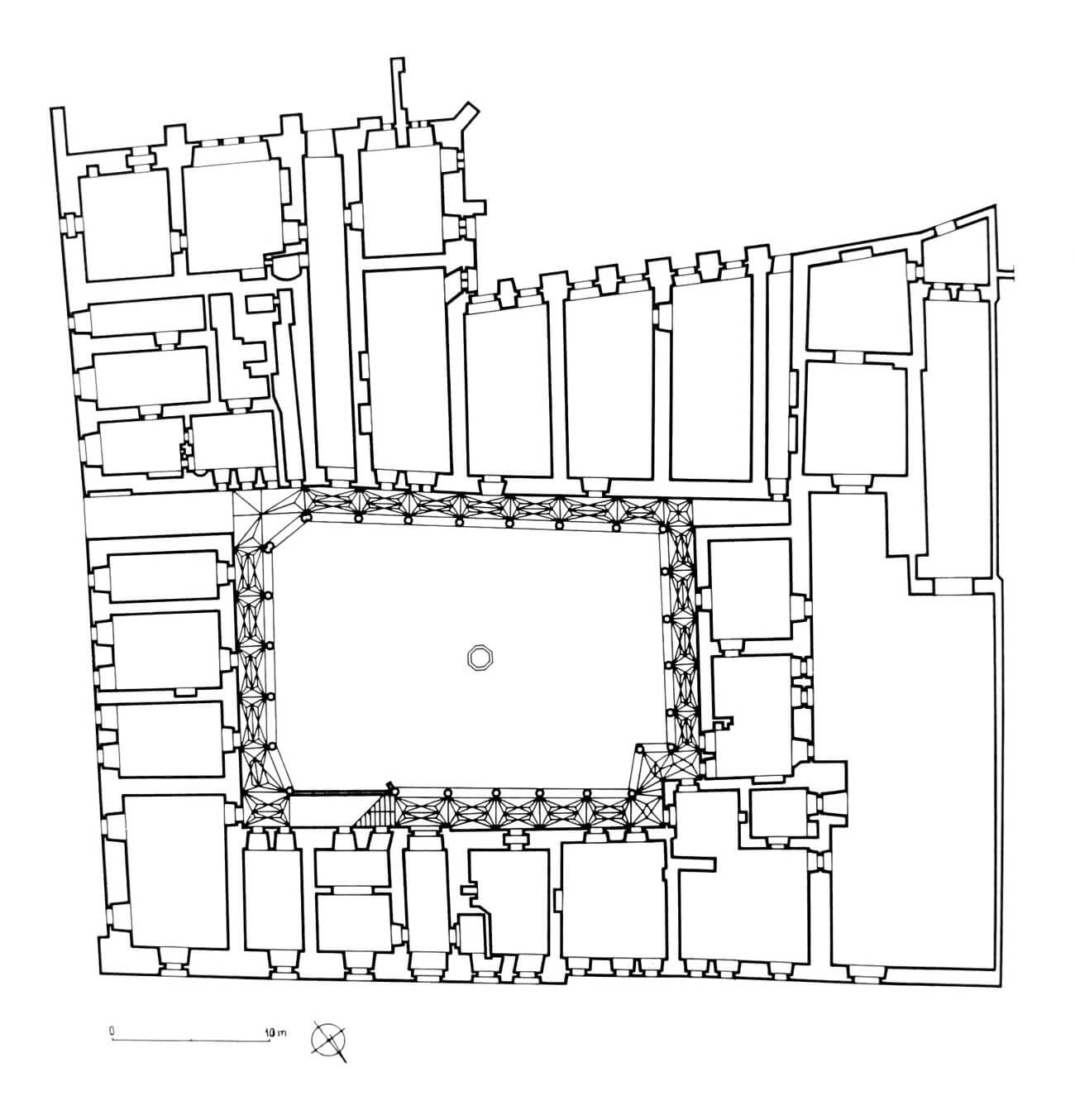

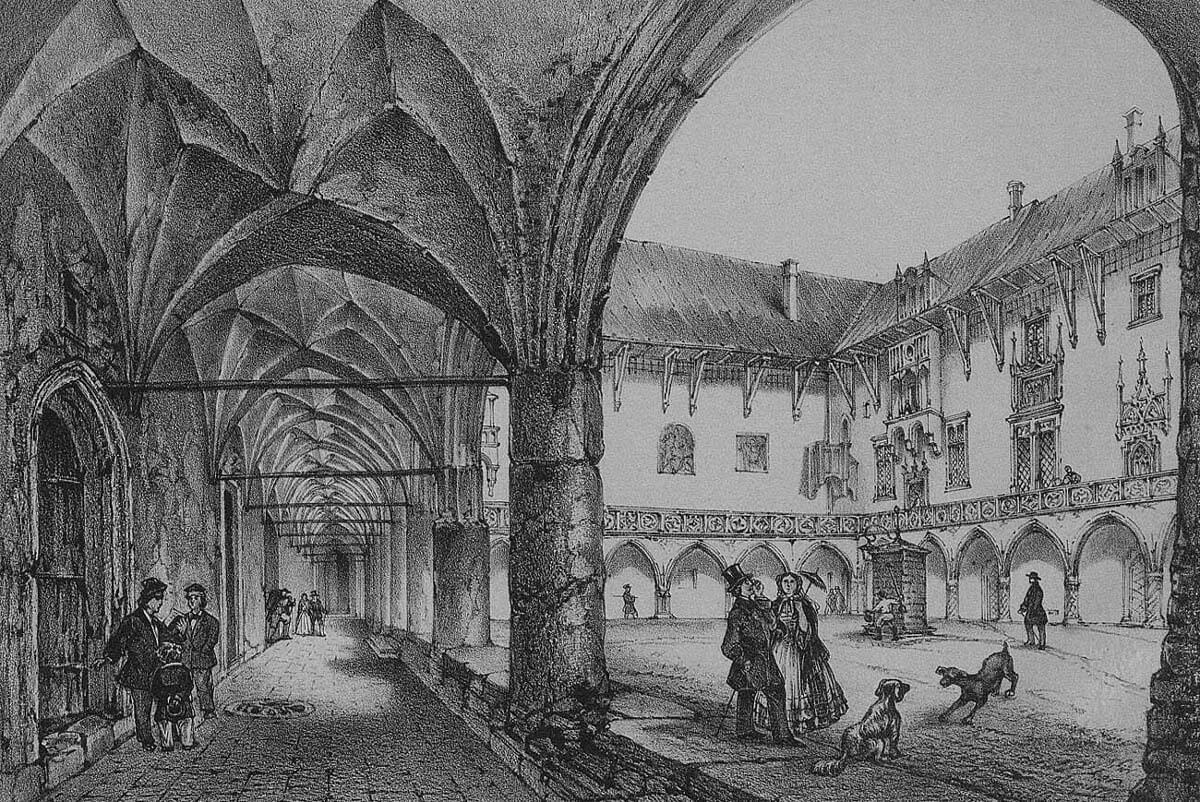

As a result of construction works from the second half of the 15th century, the town houses in the area of the college were combined into a harmonious complex, creating an arcaded courtyard surrounded by cloisters between them. The whole area was 2,587 square meters with all the buildings bricked, except for the oldest house made of stones. It was then decided that the erected buildings were to have three main floors with a basement, the first of which (ground floor) was to be used for lecture rooms, and the second and third for the professors’ apartments. The roofs were steep so that rainwater and melting snow could run off easily. At the beginning, they were covered with shingles, which were replaced with tiles in the second half of the 16th century. The facade at Jagiellońska Street received Gothic gables and a polygonal bay window. The Gothic portal led to the courtyard, which was surrounded by a cloister with a diamond vaults. Its pointed arcades were supported by moulded stone columns. Two pairs of stairs led to the first-floor porch. Water from the courtyard flowed through special sewers, drainage channels that ran under the gates to the street and further to the gutter. The canals were crossed by the pavement of the courtyard filled with limestone round stones, in the center of which there was a well from at least the end of the 15th century. In 1517, it received new lining, a shingle roof and was equipped with brass buckets.

Inside, on the ground floor, there were utility rooms (warehouses, guardhouses), a few living rooms for professors and, above all, lecture rooms. They were long, low-vaulted rooms, five to seven in number, dark and often damp, with cold walls. They were named after ancient scholars and philosophers: Socrates, Galen, Ptolemy, Pythagoras, Plato and others. They had separate entrances from the courtyard, so that students entering the rooms from inside and leaving the rooms would not be disturbed. The interiors of the lecture rooms were lit by a few windows and candlesticks, placed only by the pulpits, so that the lecturer could read books. In the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, there were no permanent benches in the lecture rooms, and students came with their own stools and benches, which they took after the lecture. In a few rooms there were boards for teaching purposes, but proffesors often decorated walls with paintings, related to the purpose of the lecture rooms (plans, maps, patterns and geometric symbols). At the end of the Middle Ages, students wrote down the words of lecturers on slate or wax tablets, using styluses, charcoal or chalk. Occasionally they wrote pen and ink on parchment and since the 16th century on paper.

Collegium Maius also housed a prison for rebellious and vicious students on the ground floor. It was an 11-meter long chamber with two recesses for bunks, the entrance to which was protected by a massive door with a lock. Over time, its walls became covered with inscriptions (not preserved to this day) created by bored inmates.

The library (Libraria) from 1519, the Common Chamber of professors (Stuba Communis) from around 1430 and the treasury were located on the first floor. There was also a richly decorated representative hall, the Lectorium Superius, also known as the Great Hall or the Jagiellonian Hall, the place of university ceremonies, and on a daily basis the lecture hall for theologians. It was equipped with five great, high-set, three-light windows, ensuring good lighting of the hall. In the 16th century, for security reasons, they were barred. In the central part, there was a pulpit for speeches, sermons and disputes, and next to it, two pairs of candlesticks were installed, which made it possible to conduct debates after dark, and benches for listeners and guests were also set up. In the years 1507-1510 the hall was enlarged and raised. Stairs, known as Professors Stairs led to it directly from the courtyard, and around 1520 a wooden ceiling was painted and decorated with rosettes with gilded roses.

Located in the central part, facing Jagiellońska Street, Stuba Communis was a multifunctional room, the heart of the college. There, professors at least once a day, and usually twice or three times, eaten meals. There also held meetings of scholars, during which, among other, rectors and other university officials were elected, discussion were made, and distinguished guests were feasted. Around 1439, the Stuba Communis was enlarged, among other things, by the bay window suspended on the facade of the building, possibly created under the influence of a similar bay window from 1390 in the Prague’s Carolinum (rib vaults were used in both). Inside there was a reading desk for a lector reading during meals, and from 1468 it was intended for an altar where services were not often held. The Common Room was covered with a wooden, flat ceiling and, as one of the first in the college, already in the 15th century, it was provided with heating, using a system of pipes placed in the thickness of the walls and led through chimneys. 20-25 professors (at the end of the Middle Ages) ate at three long tables, with cups and cutlery they brought. Initially, the kitchen was located in a separate building, which complicated the dining, due to the necessity to deliver food that was cooling down. It was only around 1508 that a new kitchen was located on the first floor of the college. Next to the Common Chamber, there was also a chamber with an archive and a treasury from the end of the 15th century. About 300 documents were then kept in a wardrobe with drawers, which were to facilitate access and keep order, while valuables, silverware, paintings or numismatic items probably lay loose.

The professors’ dwellings, or residences, were located on the ground floor, and on the first and second floors. At the end of the 15th century, there were 19 of them. They consisted of two or sometimes three rooms, the worst of which, because of dark and damp, were on the ground floor. The better dwellings on the upper floors were two-level, the most luxurious being next to the library. Between the individual rooms there were wooden doors with iron sheets nailed to them. As a rule, they were modest, without any special decorations, sometimes of poor wood, but usually locked with locks and padlocks. In the 15th century, the windows were covered with paper or a bladder stretched over a wooden frame. The bladders were greased with resin and covered with a mixture of flour and oil, thanks to which they could be resistant to frost. It was not until the end of the 16th century that these methods were replaced by glass that gave more light. For safety reasons, the windows on the ground floor were additionally covered with bars.

Built in 1519, the library or Libraria was high, five-bay. It occupied two storeys, consisting of two large, well-lit rooms with nine rectangular windows. At the time of its creation, it was one of the most progressive and magnificent in Europe, designed to be exaggerated, taking into account the future expansion of the stock of stored books (in the middle of the 16th century it contained about 8,000 volumes). The entrance to it led from the south, through the porch above the arcades, through the portal called the Golden Gate (Porta Aurea). It received a richly moulded form, topped with pinnacles and an ogee arch made of a roller twisted into a spiral on which plant decorations were placed. Above the portal there was a clock that strike the hours of classes. The interior was heated similarly to the Great Hall, so it was dry and warm, and it was also secured against burglary by putting in an iron door and barring the windows. Wooden cabinets for books were ordered for both rooms, although those most frequently used by readers were placed on pulpits under the windows and chained.

Current state

Collegium Maius is the oldest university building and one of the oldest medieval secular buildings in Poland, as well as a great example of harmonious and functional secular Gothic architecture. Its beauty and aesthetics are determined by the richness of decorations, the diversity of facades, the decorative character of gables, window openings, vaults and facades. Inside, Plato’s lecture room with a place for the scholar under the window has survived in an unchanged appearance, while in the Pythagorean lecture room there are relics of didactic paintings of ballistics and architecture, as well as geometric and trigonometric patterns. You can also see Stuba Communis and Great Hall. Currently Collegium Maius houses a museum in which collections, there are mainly items related to the history of the university. Opening hours you can check on the official website of the museum here.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Chwalba A., Collegium Maius, Kraków 2009.

Krasnowolski B., Leksykon zabytków architektury Małopolski, Warszawa 2013.

Marek M., Cracovia 3d. Rekonstrukcje cyfrowe historycznej zabudowy Krakowa, Kraków 2013.

Podolecki J., Waltoś S., Collegium Maius, Kraków 1999.