History

The formation of the medieval city was brought about by the foundation act under Magdeburg law, carried out by Prince Bolesław the Chaste in 1257. It did not mean the beginning of Kraków, which had been a tribal center of power since the 9th-10th century, but it initiated the creation of a regular grid of streets with a central market square and the division of city into precisely matched plots (“situs fori per advocatos et domorum et curiarum immutatur”), on which the construction of new residential buildings began. Its most representative part was created at the four frontages of the market square, because the first settlers and their families lived there, and there were the most influential and wealthiest townspeople houses. Among them were the founders brought from Silesia: Jakub of Nysa and Gedko Stilvoyt and Dethmar Wolk from Wrocław, who initiated surveying work on marking out the new urban layout of the city.

The rapid development of residential buildings in Kraków was temporarily halted as a result of the destruction caused by the second Mongol invasion of Małopolska in 1259. In addition, the slowdown in construction work could have been caused by the decrease in the influx of settlers, caused by political turmoil, such as the knights’ rebellion against Leszek the Black in 1285. The situation improved thanks to extensive trade privileges from the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century, as well as the commencement of construction work on the city’s defensive walls, which increased the sense of protection. In 1311, a rebellion of the townspeople led by the mayor Albert broke out against Prince Władysław the Elbow-high, but the subsequent repressions mainly concerned the elites and were to a lesser extent directed at the general urban community, which probably did not significantly affect the development of residential buildings in Kraków.

The first major changes in the spatial layout of medieval houses in Kraków were brought about by the beginning of the 14th century, when, due to the inconvenience of moving to the back of the plots, the layout of large halls in the ground floors of buildings began to be changed in large numbers. The economic development of the city in the second half of the 14th century, associated with favorable economic and political conditions during the peaceful reign of King Kazimierz the Great, led to an even greater revival of construction activity. At that time, customary building regulations were codified, which contributed to regulating the process of erecting burgher buildings and establishing a standard house, in which the form resulted from its function (among others, in the resolution of 1367, the principles of building boundary walls of tenement houses were developed). Moreover, at that time, amenities began to be introduced on a larger scale, such as paved streets in front of the most important lines of the buildings or the first waterworks providing access to clean water.

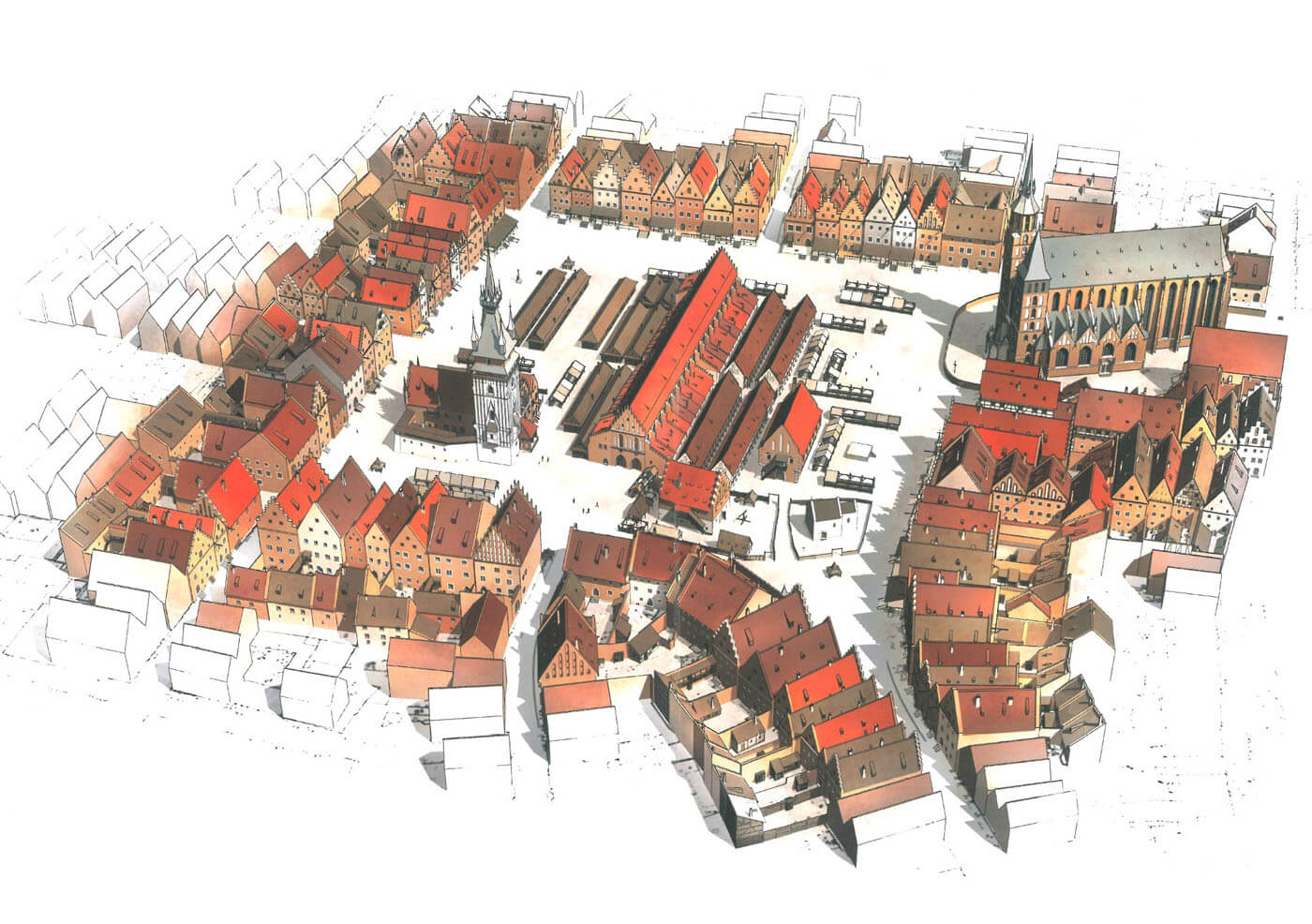

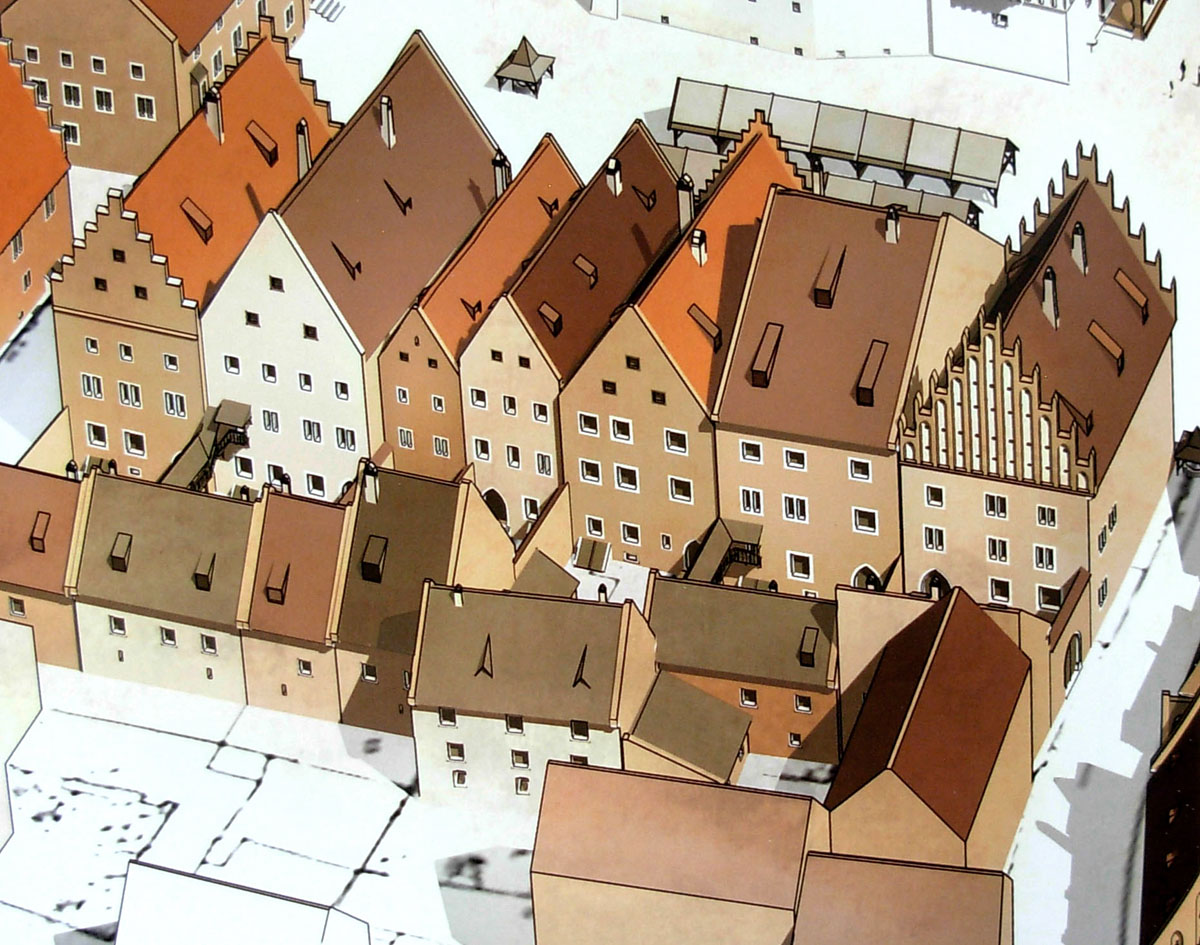

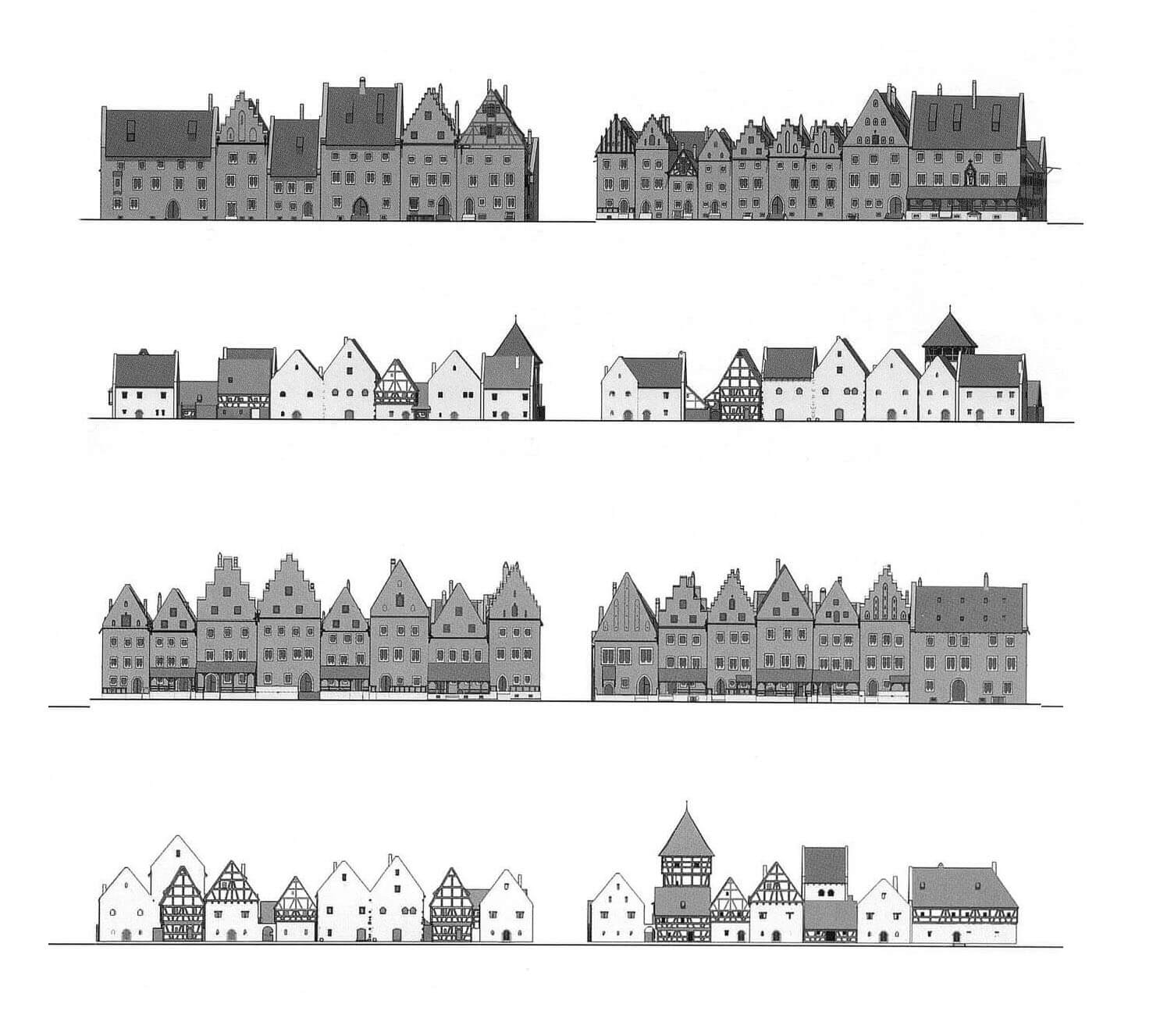

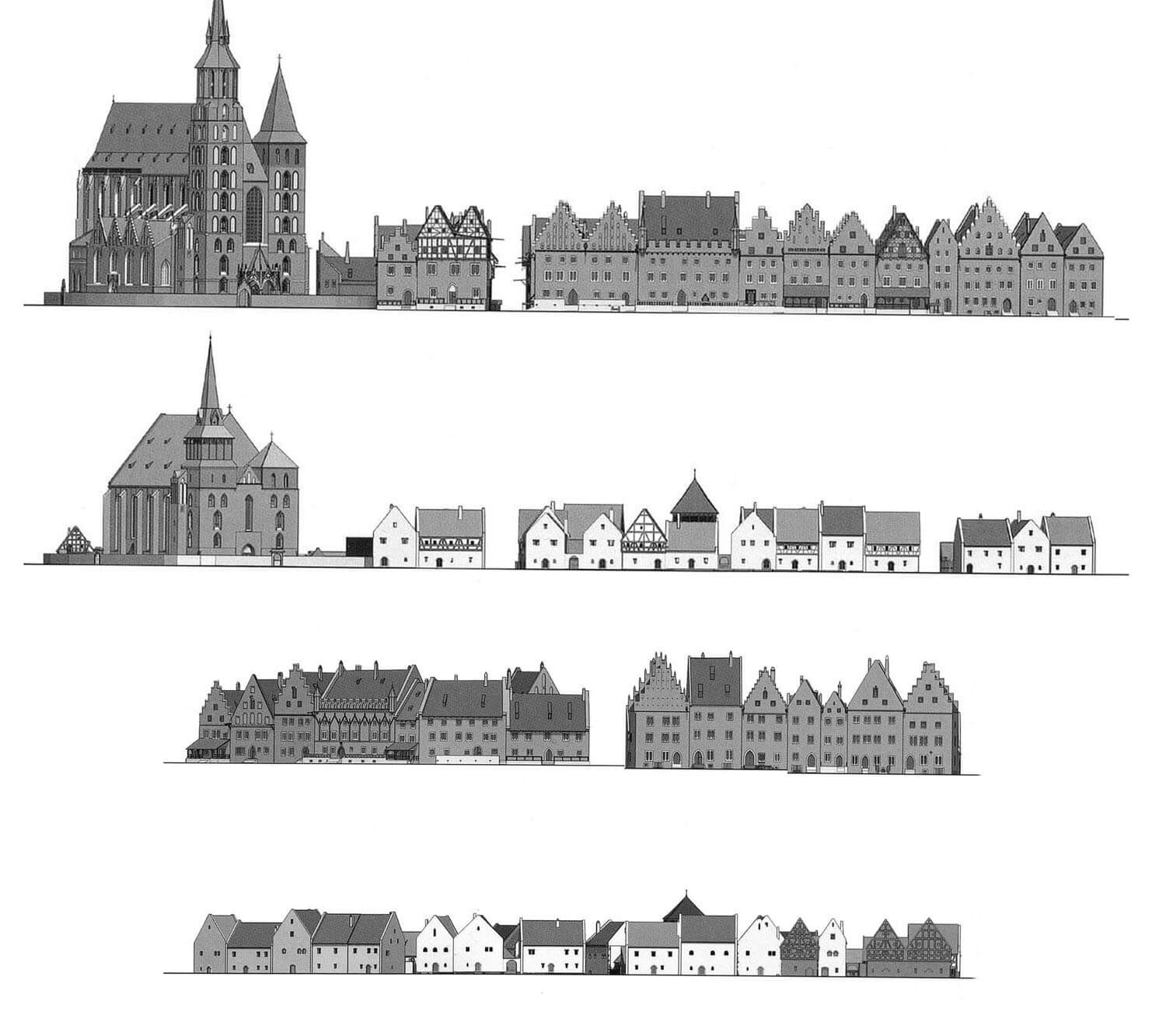

At the beginning of the 15th century, Kraków with a population of around 13-14 thousands, was a medium-sized European city, but its development was influenced by international connections resulting from its function as the capital of a kingdom and bishopric, the seat of numerous religious orders, an university, and a supra-regional trade center. For this reason, Kraków more closely resembled more populated cities in the West, and its urban planning and architecture definitely distanced from other centers in Małopolska, or even in the entire Kingdom of Poland at that time. During the 15th century, construction processes led to the displacement or transformation of the original residential buildings from the 13th and early 14th centuries, largely wooden or half-timbered, replaced by more impressive Gothic brick buildings. The 15th century was the apogee of the architectural development of the medieval city, especially in terms of quantity.

At the end of the Middle Ages, Kraków, with a population of around 19 thousands, was the second largest city in Poland after Gdańsk, diversified in terms of class, wealth, profession, and ethnicity. The growth of the population was hampered by frequent epidemics, the greatest of which was the plague of 1543. In addition, the population and housing were affected by natural disasters, primarily fires. In 1523, the area around the Shoemaker Gate burned down, in 1528 the north-eastern part of the city, in 1530 the buildings on the southern streets of Grodzka and Kanoniczna, and in 1546 Sławkowska and Szczepańska streets burned in the north-western part of Kraków. The buildings were also modernized due to changes in utility related to the conducted activity (e.g. Carpenter Street lost the character associated with its original residents in favor of various professions), the model of life, or the condition (e.g. the conversion of burgher houses into residences of nobles).

Early modern changes in the medieval layout and appearance of tenement houses began on a larger scale in the third quarter of the 16th century. Renaissance decorations began to appear, staircases were introduced into interiors, first-floor halls were transformed into living quarters, attic stores and warehouses disappeared, and tenement houses began to be divided into autonomous parts used by different families. Due to fire regulations, the gable roofs disappeared, so strongly associated with the Middle Ages, replaced by so-called sunken roofs, with a slope layout reversed in relation to the former roofs. Finally, around the middle of the 17th century, due to the gradual displacement of Gothic architecture, the residential buildings of Kraków largely took on an early modern appearance, although the core of houses hidden beneath it still remained medieval. Neither Renaissance, Mannerist, or Baroque transformations, nor even later modernization works, completely removed this phenomenon.

Architecture

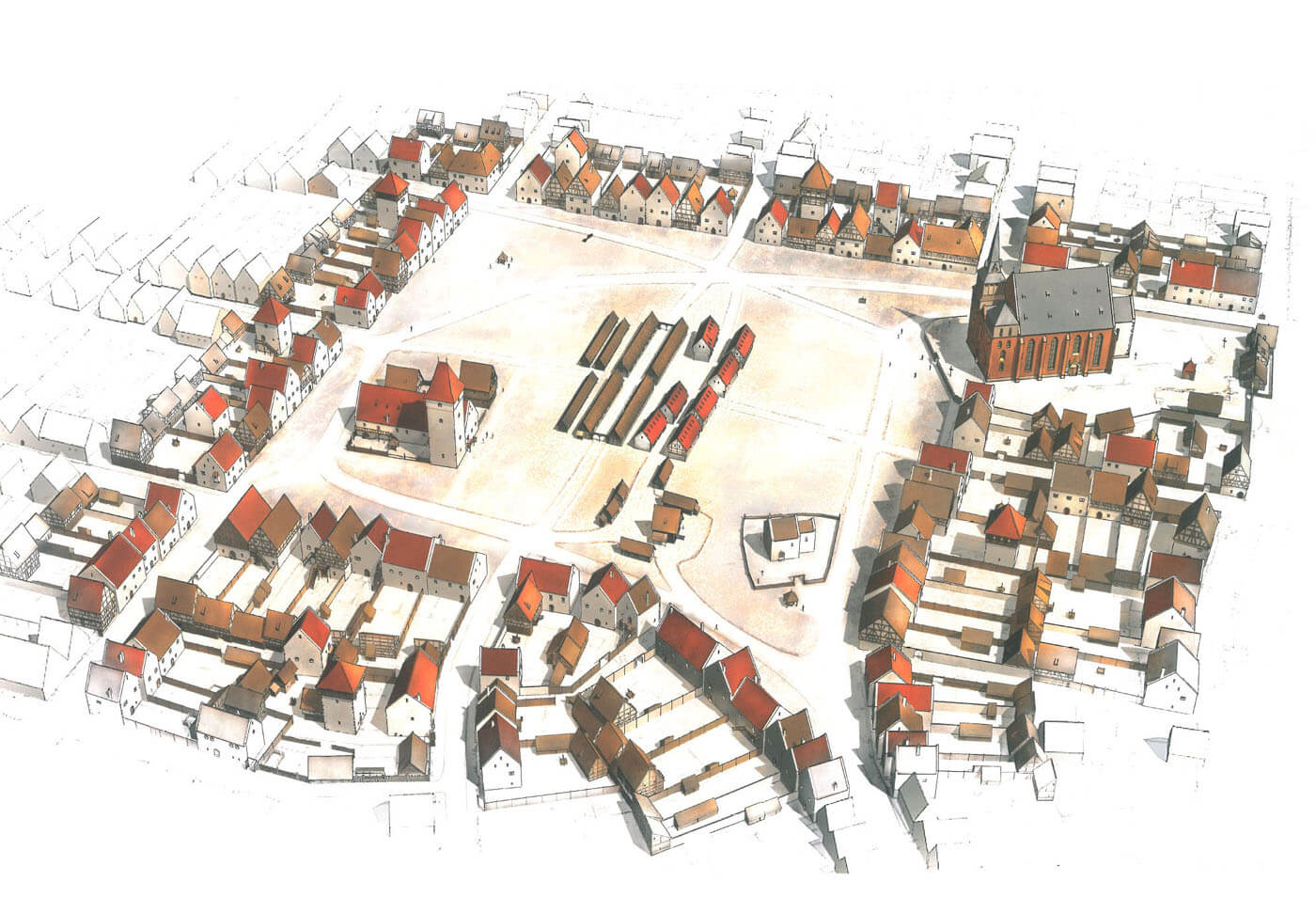

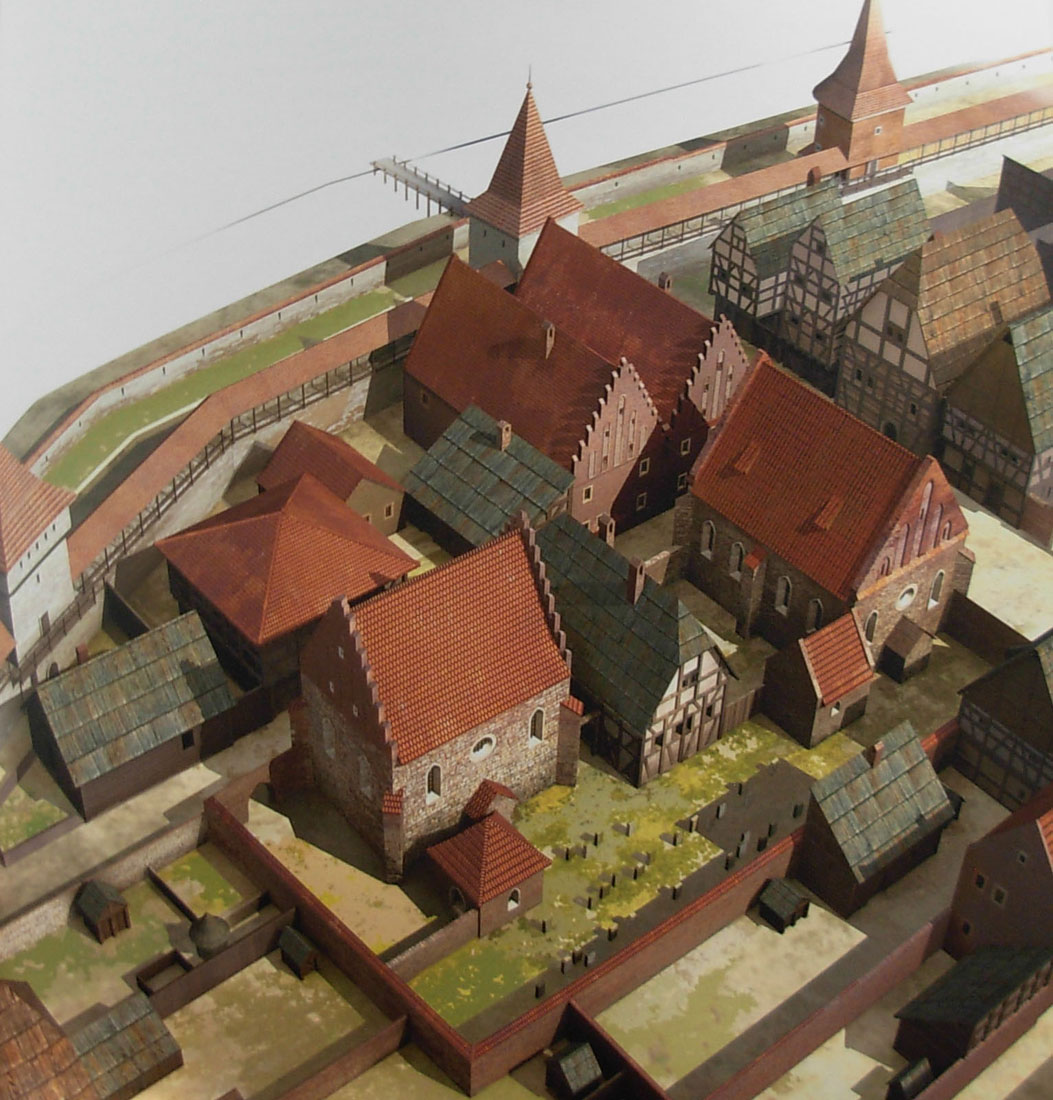

The development of the urban buildings of medieval Kraków initially took place within the zone located north of the Okół outer bailey and the Dominican and Franciscan friaries operating there. This area was already developed in the pre-foundation phase, it had its churches, residential buildings and crafts, but it was destroyed during the Mongol invasion. As part of the reconstruction and founding of the city, the space was divided into nine squares, the central of which was the market square, and the others surrounded it on all sides. Each of the squares designated for development was to be divided into four blocks of development divided by streets, with sides of about 84 meters. However, significant obstacles, such as the location of the churches, the older communication network and the future city walls, did not allow for the full implementation of such an ideal project. As a result, a structure with strongly emphasized regularity was obtained, but not perfectly symmetrical (the area located south of the market square with the road to Wawel Castle was left irregular). The relative uniformity of the Kraków plan did not mean that the quarters were quickly filled with buildings, although it turned out to be stable.

The market tenement houses were largely representative of all medieval Kraków houses. Their construction, interior layout and the way of shaping referred to the buildings on other streets. The differences were expressed only in grandeur (number of storeys), quality of building materials (including the proportion of stone and wood) and ornamentation. After the city was founded, the Kraków market square was divided into 30 large, mostly elongated plots measuring about 42 x 21 meters (called curia), facing the square with their shorter sides. On these plots, after their division into slightly smaller half-curias, 68 houses were built in the first phase, of which the length of the facades facing the market square was on average about 10 meters. The square blocks mentioned above were constructed from eight plots, with the ones by the market square consisting of four full plots facing the square and two pairs of plots facing the streets running off the square. The remaining blocks had four pairs of plots facing those streets. The plots in Kraków were exceptionally large compared to other Polish and Silesian cities, so it were divided quite quickly for practical reasons.

The oldest brick houses in Kraków were built of limestone, carefully selected but not processed with tools, laid in layers 0.6-0.7 meters high, separated by smaller stone fragments. Occasionally, the limestone was supplemented in architectural details with bricks (edges of portals, jambs, lintels, edges of windows, and also niches in the walls). Initially, Kraków houses did not have basements, because the walls were set in the ground without an extensive foundation to a depth of 0.5 to 0.8 meters. The height usually reached two above-ground storeys. Perhaps some houses had additional storeys of wooden or half-timbered construction. This would have been possible thanks to fairly thick peripheral walls, on average about 1.2 meters wide in the ground floor. Plans of the houses usually had forms similar to squares measuring 10 x 10 meters or not very elongated rectangles. Among them, buildings on corner plots often stood out for their size. Kraków residential buildings were originally austere and monumental, almost devoid of decoration, limited to window and door frames or corbels for ceiling beams. At that time, houses were covered with ridge or gable roofs, hip and gable.

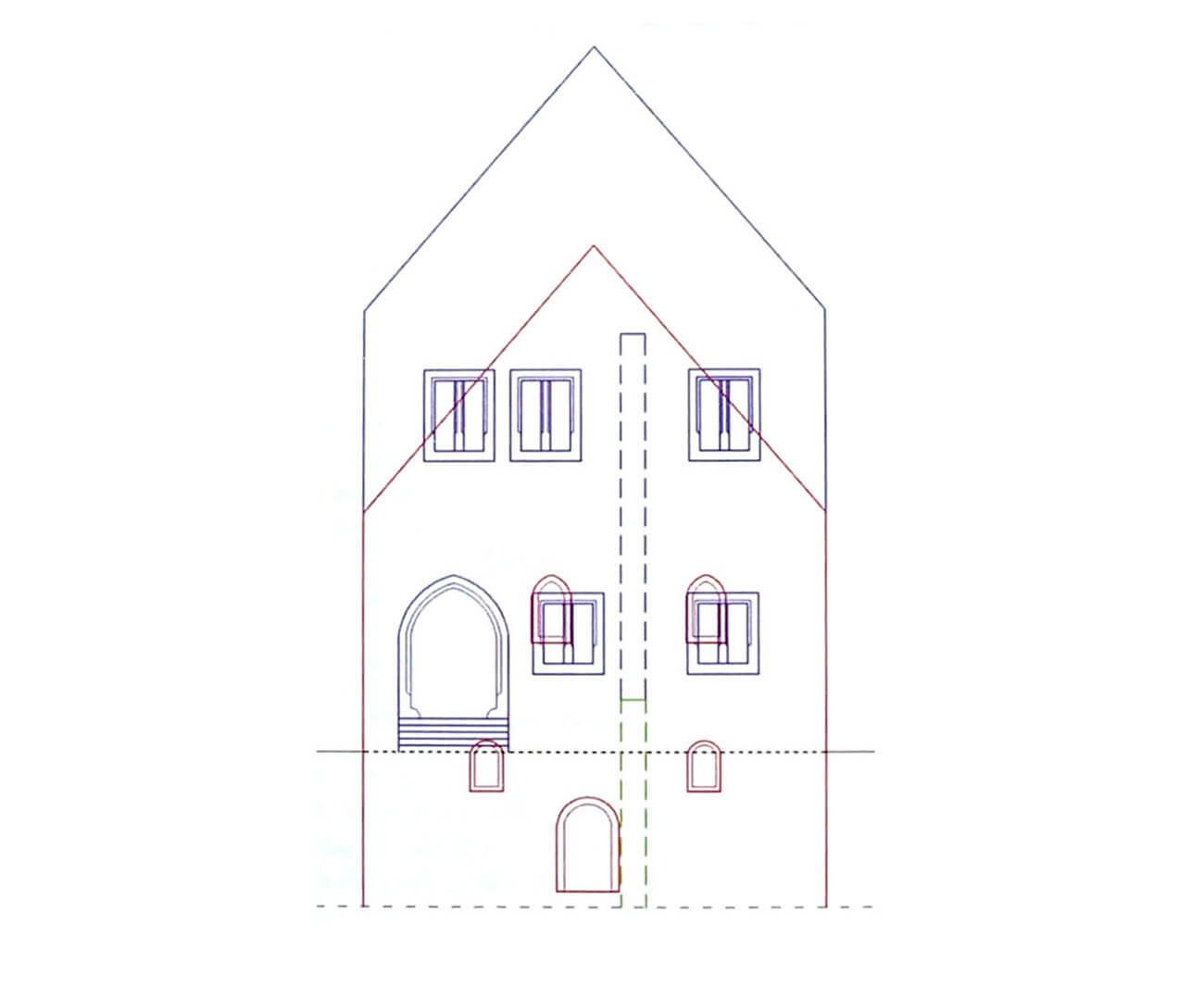

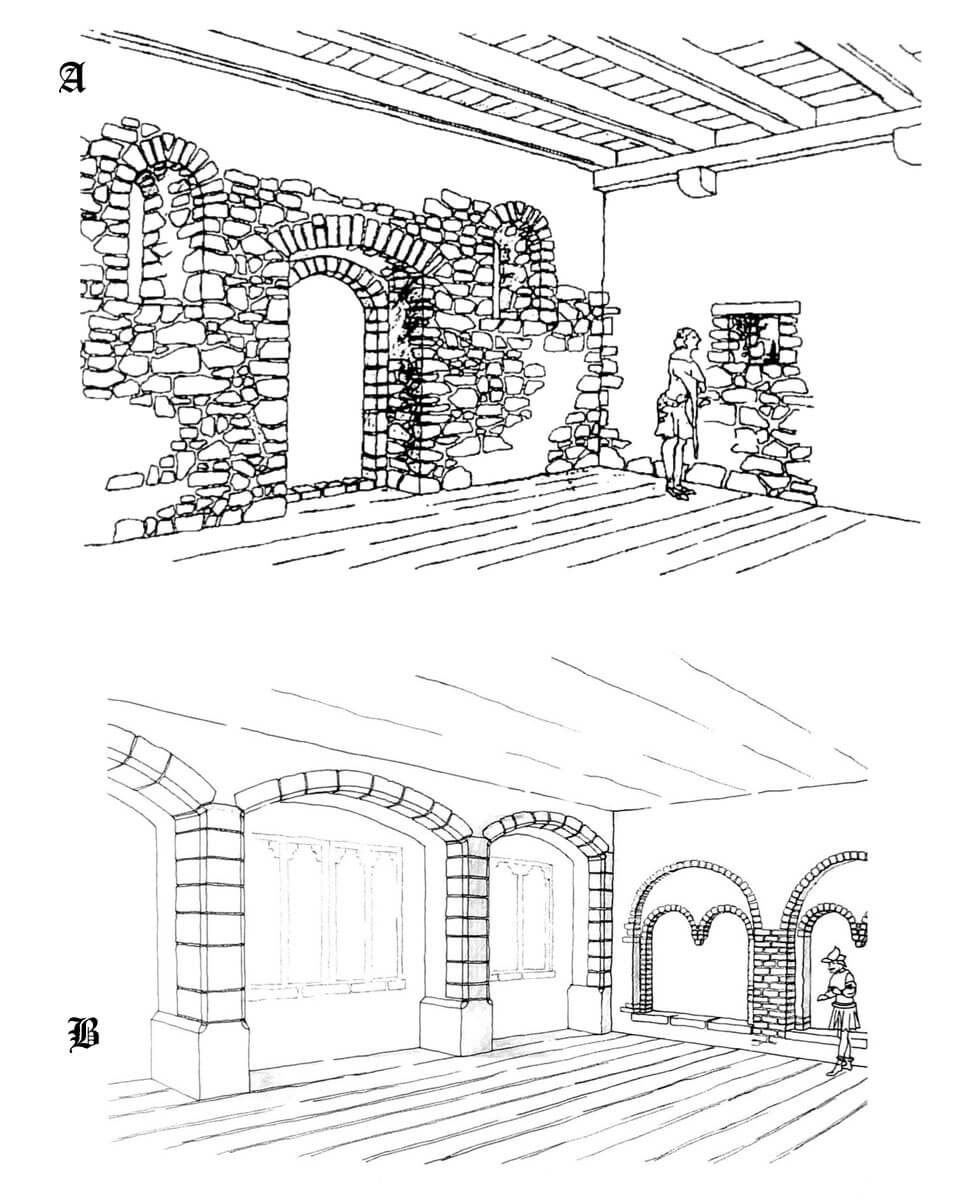

The ground floors of houses from the second half of the 13th century were covered at a height of about 3-4 meters with beam ceilings, supported on offsets or less frequently on stone corbels. Their walls were usually plastered and whitewashed inside. The interiors were filled with a large, single-space halls, which housed a craft workshop, a goods warehouse, as well as a residential and utility space heated by fire from an open fireplace with a hood. The hall was usually lit by two small windows, placed on both sides of the entrance portal, usually placed symmetrically. There were also entrances in the back wall from the yard side. This location of the main entrance allowed the fireplace to be placed by one of the side walls of the building. The width of the entrances was not very large, only about 0.9-1.2 metres, so they were not passable for carts. The finds of keys would indicate that the buildings were locked from the 13th century onwards. Access to the floors was provided by wooden, often external, rear stairs, and probably also by ordinary ladders. Only some of the oldest houses in Kraków had floors accessible from the outside by stairs placed in the thickness of the wall. Upper floors probably contained living quarters, for example bedrooms, divided by wooden partition walls.

The entrances of the oldest houses in Kraków were made of bricks, topped in a semicircle and placed in wide niches with almost no embrasures, while the niche lintels were made of two straight and narrow limestone blocks, connected at an obtuse angle. The windows had a similar construction, but were much smaller on the lowest floors. Possibly larger windows could function on the upper floors of the buildings. There were individual solutions, different from the commonly used ones, such as stone portals, pointed windows, or exceptionally pointed arcades. Inside the houses, quite a few niches and recesses were placed in the walls, acting as storage spaces, shelves and cabinets. As a rule, they had dimensions of about 55 x 55 cm. Their depth was not great. The niche lintels were made of thick oak boards. Small niches with brick edges and a lintel made of two bricks arranged diagonally were also created.

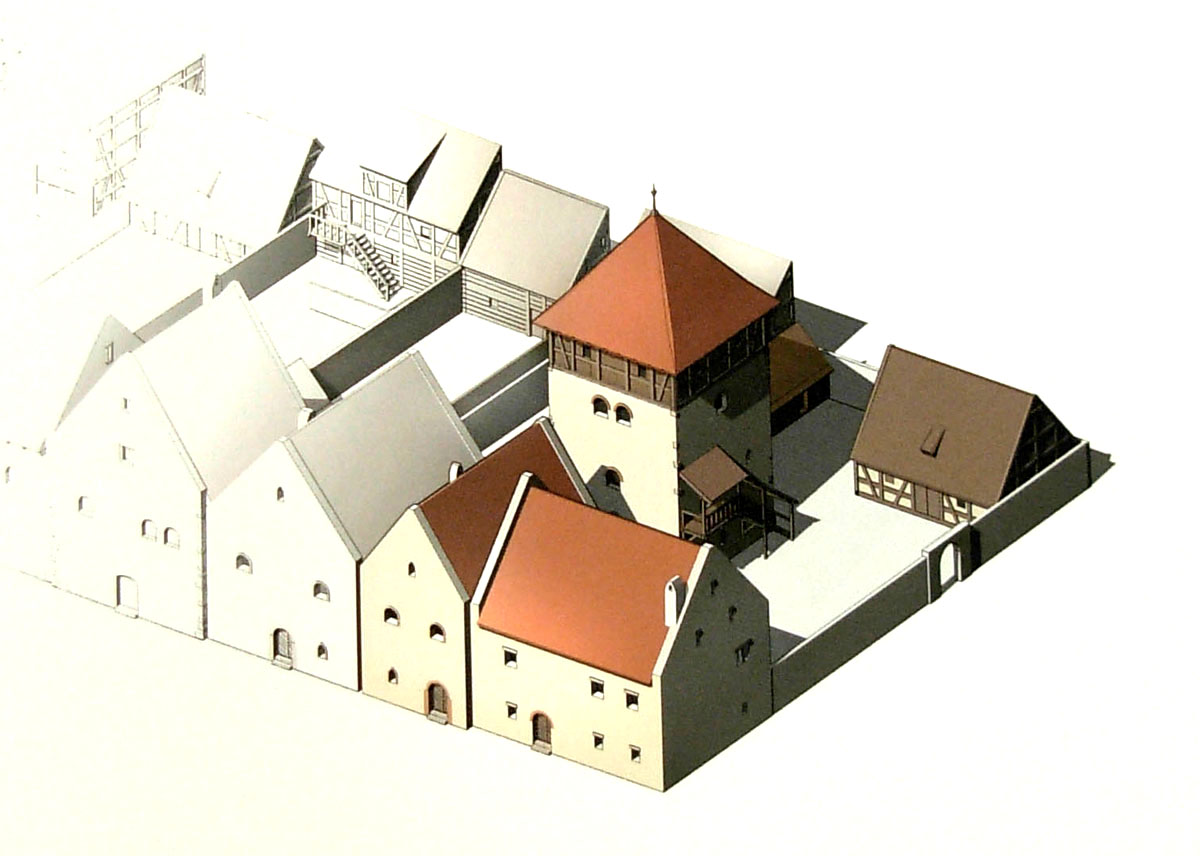

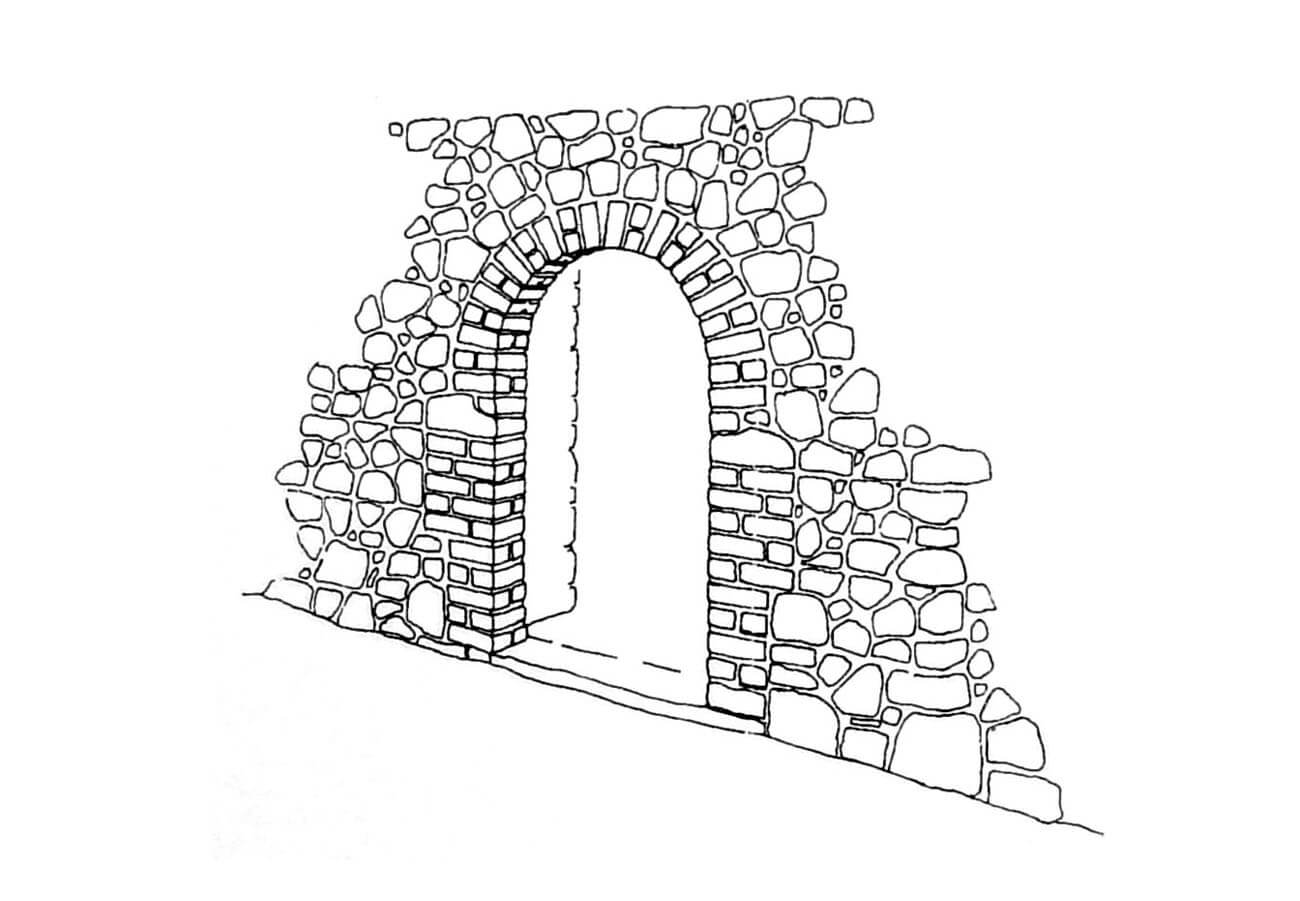

At the back of the plots there were wooden auxiliary, utility buildings, probably mostly single-storey. To allow for better access, sometimes 2.6-3.8 metre wide passages were left between the buildings. Therefore, at the end of the 13th century, the Krakow development was not yet compact. The problem of access to the back of the plot did not occur in corner buildings either, where the outbuilding could be reached through a gate in the wall or fence separating the courtyard. Sometimes, instead of auxiliary wooden buildings, brick, usually three-storey buildings on plans close to a square and in forms similar to towers were erected at the back of the plots (seven such buildings have been identified in Kraków so far). They combined residential, representative and defensive functions, important due to the repeated Mongol invasions in the 13th century. Their sides were 6 to 10 metres long. Each storey originally contained single-space interior, accessible directly from the first floor or sometimes from the ground floor. Their doorways had semicircle heads or with a slightly marked break in the arch, while the lintels were shaped as segmental arches. The window heads were also semicircular or slightly pointed.

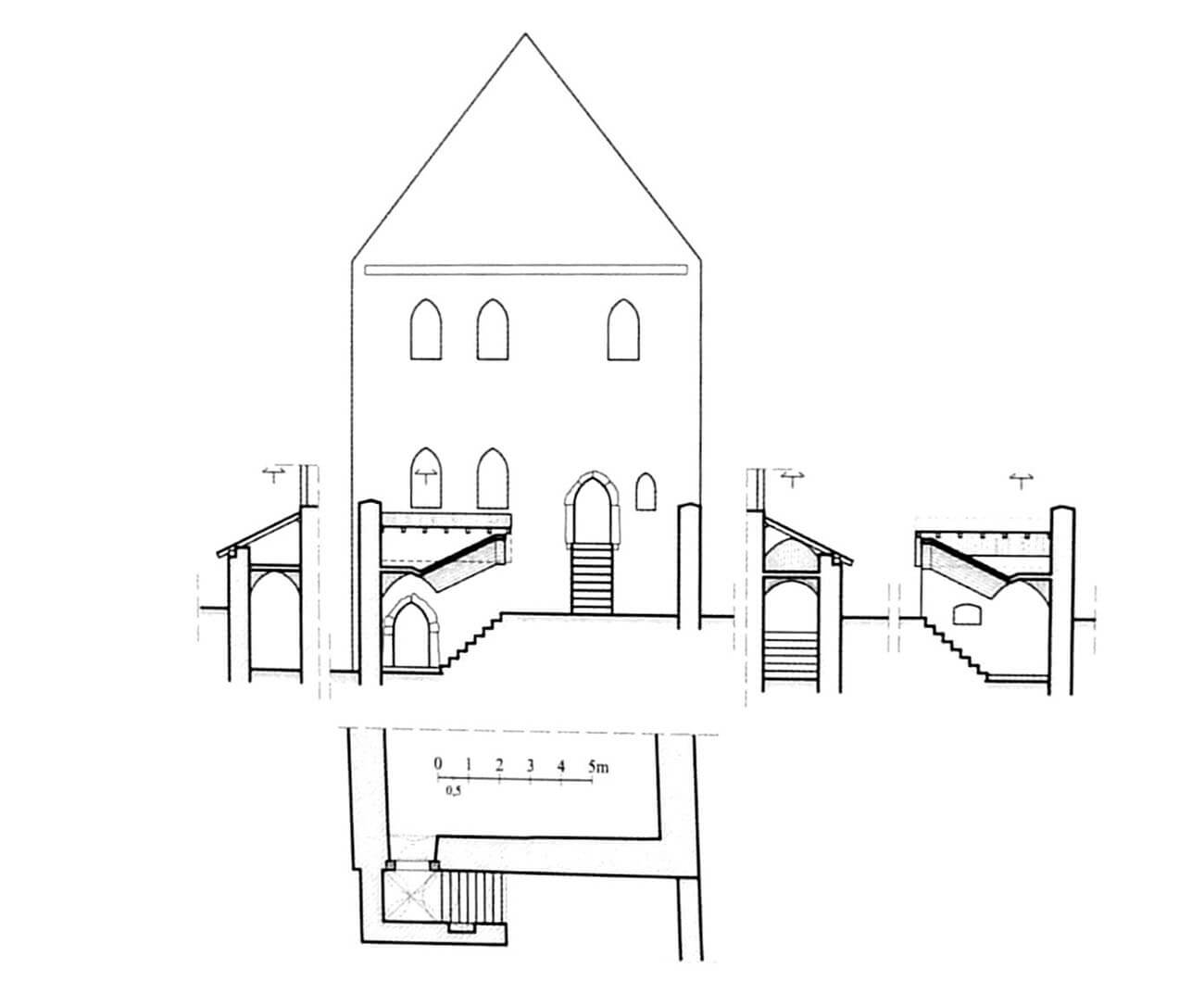

Among the tower houses was a residential tower associated with the person of Henry, brother of mayor Albert, known as the leader of the townspeople’s rebellion in 1312. It was built on a square plan with a side of about 9 meters, with a wall thickness of 1.2 meters at the ground floor. It was located in the middle of the plot, had three storeys, and its height exceeded 13.5 meters. The storeys were divided by beam ceilings supported on offsets. The ground floor was less than three meters high, and the first floor was about 4.8 meters high. The semicircular entrance to the ground floor was located in the eastern wall, i.e. from the side of Bracka Street. On both sides of the doorway there were small, pointed windows, and a niche above it. The entrance to the second storey, accessible from the outside, was located in the northern wall.

The first brick houses in Kraków were of a type of building that appeared throughout the entire northern European area at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, with the only difference being that Kraków houses (similarly to Silesian houses) usually had a residential upper floor, which was not always present in the North. A characteristic feature of the tenement houses in the northern region, apart from the lower, large hall, were floors used for storage and warehouses. Therefore, Kraków houses were influenced by the Mediterranean architecture, which spread along Tuscan-Lombard and French patterns to southern Germany. Moreover, the oldest Kraków houses showed connections with Kraków sacral buildings (the Dominican friary, St. Nicholas’ Church) and defensive buildings (the city walls, Wawel Castle) in terms of construction technology.

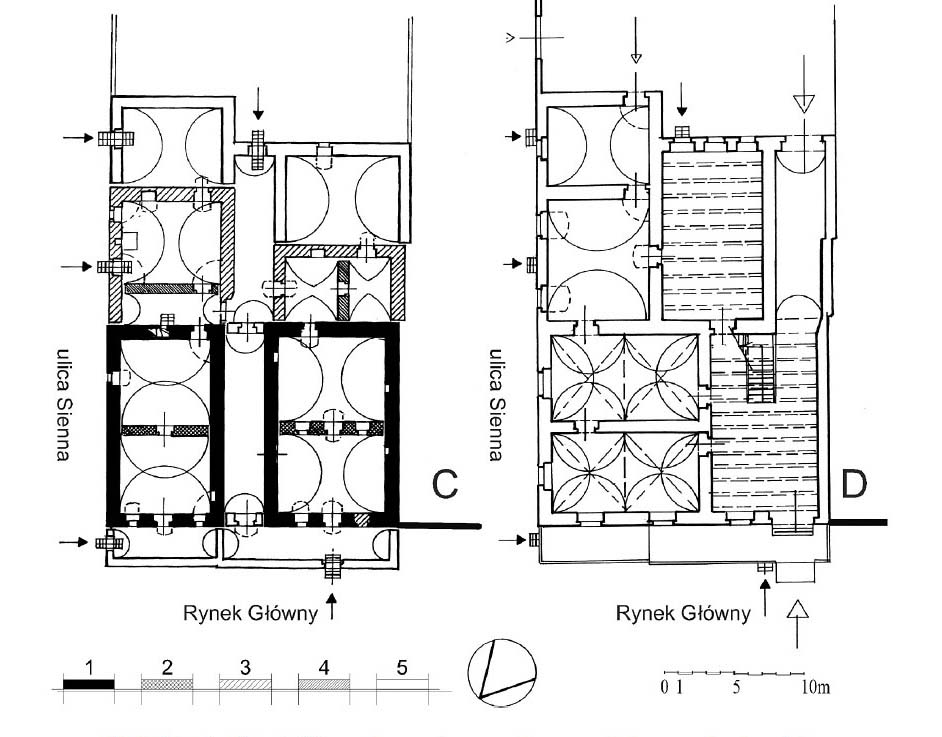

In the first half of the 14th century, the second stage of development of medieval brick tenement houses in Kraków began. At that time, the original single-space, large halls located on the ground floor began to be divided into smaller rooms. When the house stood in a compact frontage without the possibility of access to the back of the plot from the outside, the spacious halls was divided lengthwise into two rooms (a hallway and a shop). They were of different widths due to the entrance to the building located on the central axis of the facade. When the original entrance to the tenement house was bricked up, it was possible to divide the hall into rooms of equal size. The third, rarest variant of dividing the hall was possible in houses with the access to the back of the plot through a side passage (e.g. in corner houses). In this case, the hall was divided by a transverse wall, parallel to the building’s facade.

In the mid-14th century, the process of erecting brick houses in Kraków intensified so much, that the tenement houses began to create compact frontages. In addition, an important factor in shaping the development was the intensive increase in the height of the ground, which led to houses sinking deeper and deeper into it. The thickness of the new layers exceeded two to three meters, reaching four or five meters in some places in the following century. This was caused by the destruction of old houses due to fires, or their deliberate demolition, but above all by the failure to remove garbage and the successive layers of cobblestones or wooden logs. Various waste ended up on the streets: sand from digging basements, foundation trenches and cesspools, clay left after the construction of half-timbered houses, and ash from furnaces and fireplaces. All this quickly raised the level of the ground around the houses, especially the streets and city squares, but also the undeveloped parts of the plots.

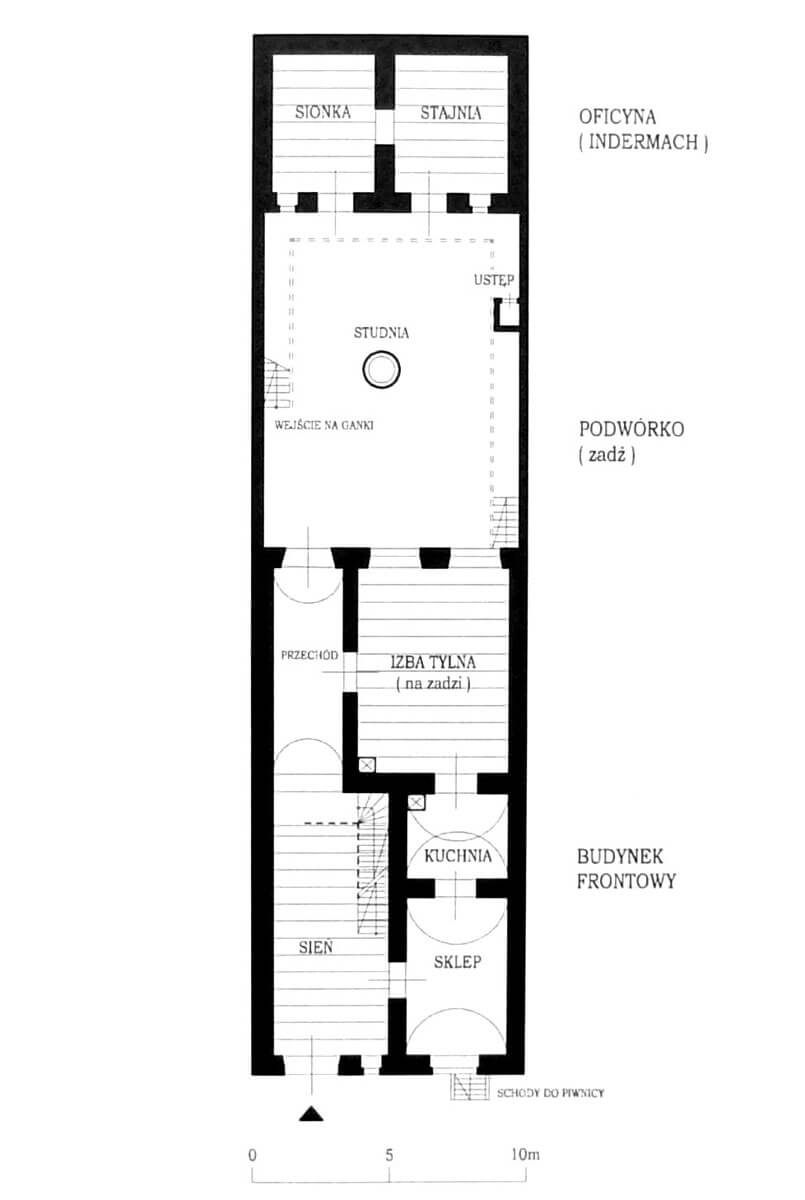

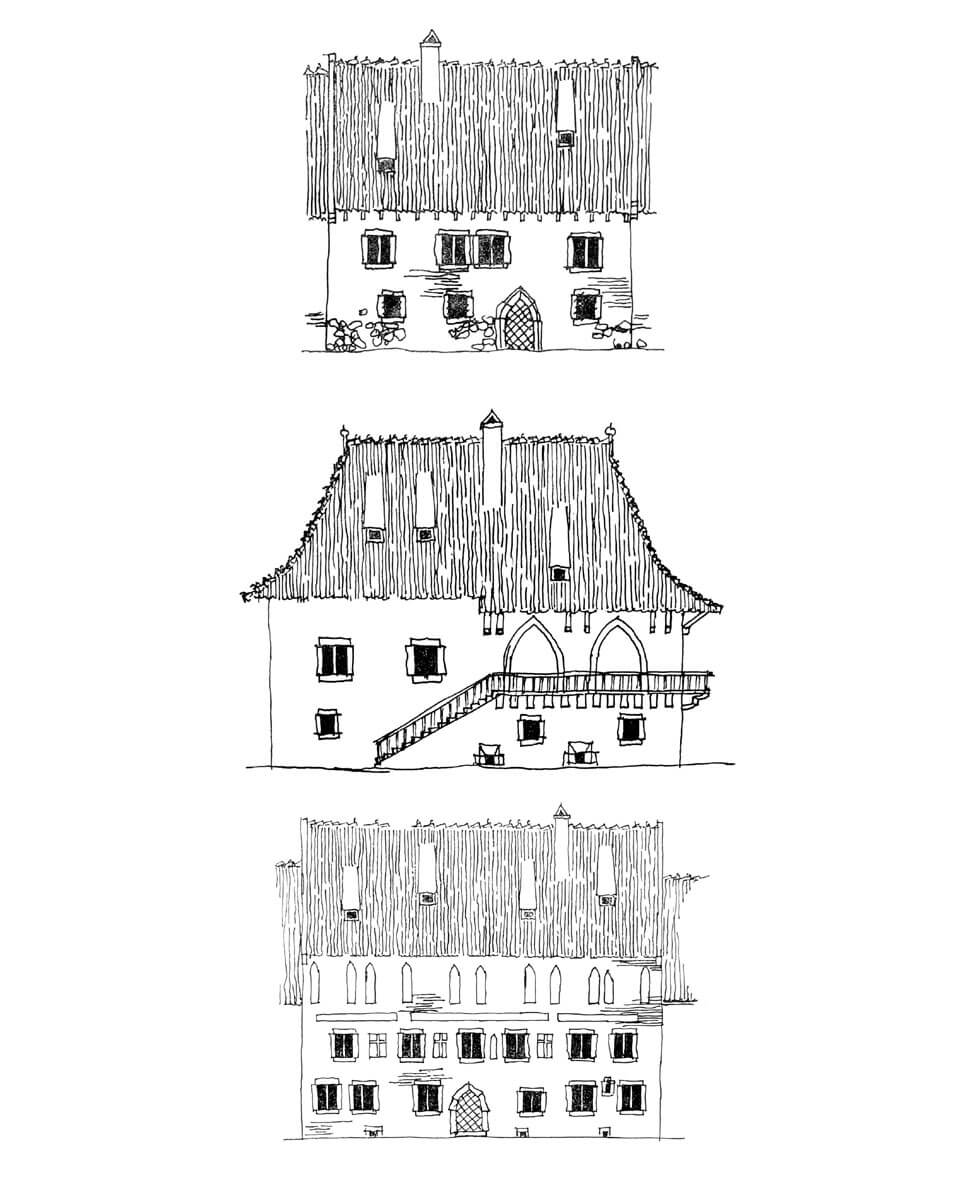

The third stage of house transformations from the second half of the 14th century involved enlarging by adding rear bays, adding floors and building brick outbuildings. As a result, a medieval tenement house with Gothic decorations was created with three floors: a basement, a utility or representative ground floor and a residential upper floor. Most of the buildings on the market square and perhaps also some of the houses in other parts of the city from the second half of the 14th century and from the 15th century were already three-storey. The tenement houses were covered with high roofs with steep slopes. Shallow, single-bay houses could be covered with both ridge and gable roofs, while two-bay houses probably had mainly gable roofs. The external elevations, although had carefully jointed bricks, could be covered with thin layers of plaster, on which colourful imitations of nobler materials were painted, for example, a pattern of stone ashlars, tracery or friezes. Roofs received a shingle or ceramic sheathing. The gables were decorated with blind windows, pinnacles or decorative battlements. They were fitted with small windows to illuminate the attic and cranes with booms to pull goods into the warehouses. On the upper floors, one of the windows was often set back from the pair of other windows illuminating the upper hall. On the ground floor, the entrance opening was usually located closer to one of the edges of the façade, and a small window next to it illuminated the room. The second, slightly larger window was associated with the shop. The rear elevations contained entrances to the passages of the rear bays and windows were often arranged asymmetrically, similarly to the façades. The rear outbuildings, were connected to the main tenement houses with wooden communication porches, suspended on the boundary walls.

In tenement houses from the second half of the 14th century, the original halls, after being embedded in the ground level raised by 2-3 meters and transformed into the basements of the front section, began to be covered with barrel vaults. The formation of the level of these vaults was influenced by the so-called water law, which prohibited the discharge of rainwater to the adjacent plot. Therefore, attempts were made to raise the level of the ground floor of the house in order to drain the water through a covered gutter to the street. Gothic halls from the 14th century filled the second storey, i.e. the then ground floor. They were still covered with ceilings, with the beams resting on offsets in the walls or on stone corbels. The walls of the upper floors usually repeated the layout of the rooms on the ground floor and before the mid-14th century their single-space interiors began to be divided into smaller rooms, just like the ground floor. Access to them was provided by external wooden stairs placed at the back wall of the house. Less frequently, the first floor was accessed by stairs placed in the thickness of the wall or in the hallway of the back bay. The main feature of the new back bays was their division into a spacious room and a long passage to the backyard. This rule could be broken in corner houses, where there was no need to create additional passages and the back bay was divided into two equal rooms. The division of the back bays into two rooms of different sizes was also maintained on the upper floors, and both of these rooms could be directly connected or, more rarely, accessible only from the front bays and back doors from the yard.

In the third phase of the expansion of Kraków tenement houses, some houses received stoops, i.e. narrow cellars at the facade of the buildings, raised above the ground level, on which there were terraces accessible by stairs. They did not create a communication route, but were built separately for each building. They had different heights and widths, oscillating from 2.5 to 5 meters. They made possible to enlarge the usable space of the building, cover the entrance and isolate the ground floor from street traffic. They also served as ramps for unloading goods from carts, some of which (the smaller ones) could be carried directly to the basements. The terraces were covered with wooden roofs, which began to be removed in the 16th century due to the fire hazard. Stoops were built mainly at the main market square and smaller city squares, and much less often on other streets. They were a characteristic element of medieval Kraków, but they influenced the lack of arcades near the market square.

The front building in the Gothic period occupied half of the plot, while the remaining part was occupied by economic buildings, including the aforementioned outbuildings. Courtyards were usually situated at a higher level than the street surface, which allowed rainwater and sometimes even sewage to be drained through the hallways. Local modifications occurred when the layout of the terrain and development made it possible to lead a gutter to a side street. On Krakow’s market square properties, where the ground level was much higher than on undeveloped properties, owners obtained permission to drain water through canals (“canale seu aquefluxum aubterraneum”) at least since 1397. After obtaining permission, it was also possible to drain water through a neighbor’s plot. Sometimes it was drained directly into the city moat, which happened mainly in the case of properties located on the outskirts of the city, but also those located deeper. In the rear courtyards of Kraków tenement houses there were wells and cesspools with latrines, which were accessed through wooden porches on the second floors.

The outbuildings occupying the rear parts of the plots were much smaller than the front houses. As a rule, they were single-storey, single-bay, covered with lean-to roofs. Side outbuildings were rare in medieval Kraków, because they were definitely more often built on the opposite sides of the front tenement houses. Their interiors housed stables, coach houses, barns, warehouses, and less often residential rooms. Some of the outbuildings took the shape of towers, but they did not have the form of solid tower houses from the 13th-century stage of the city’s development. In exceptional situations, the external elevations of the outbuildings were decorated, for example with pointed panels.

At the end of the 14th century, the houses on almost all the plots near the market square were already of brick construction, although their rear bays were still made of wood in about one third. Wood certainly predominated in the construction of the rear upper floors of the buildings. On the streets leading away from the market square and further away, brick development was less intensive. Grodzka Street, leading towards the castle, had the relatively densest brick buildings, especially in the western frontage. About every second or third house could be made of wood on the other streets leading out of the market square, and even more wooden or half-timbered buildings could be found on the outer streets, near the city defensive walls, although the general density was equally high everywhere. Among the brick buildings, from the second half of the 14th century, bricks began to predominate over stone, which was used only for the foundations of new buildings and for architectural details. A significant increase in the number of brick buildings took place in the 15th century. Brick tenement houses were built on the sites of older wooden ones, but due to the increase in population, new houses were also built on divided properties (although the process of dividing plots was less intensive than at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries). At the end of the 15th century, the front buildings of the market square were made entirely of brick and sotne, as were the houses along all the most important streets of the city. Brick rear bays became the standard. Only in smaller side streets and in the peripheral areas of the city did brick buildings alternate with wooden ones.

Late medieval houses in Kraków from the 15th and early 16th centuries were most often family buildings, where merchants or craftsmen lived with their servants, running shop or workshop. They usually contained one kitchen, located in the front part or in an outbuilding, and one large room intended for work, located most often in the back bays. In Kraków, unlike other northern cities, no representative room developed in the front part of the house, where the halls were rather utilitarian in nature, with sparse decorations and very sparse vaults. Important rooms, however, were the front halls on the first floors, where common rooms were arranged, in which the paths of all household members crossed. This was where the wooden stairs from the lower halls ended, and the stairs, or rather ladders, to the attics or second floors began. Entrances from the halls on the upper floors led to adjacent rooms in the front bays or to rooms in the rear bays. As families grew, the upper halls were converted into apartments, which required separating the communication sections. In late Gothic tenement houses, people slept in various places, but most often on the upper floors, in heated rooms. The attics had a significant volume, probably intended for storing merchant goods.

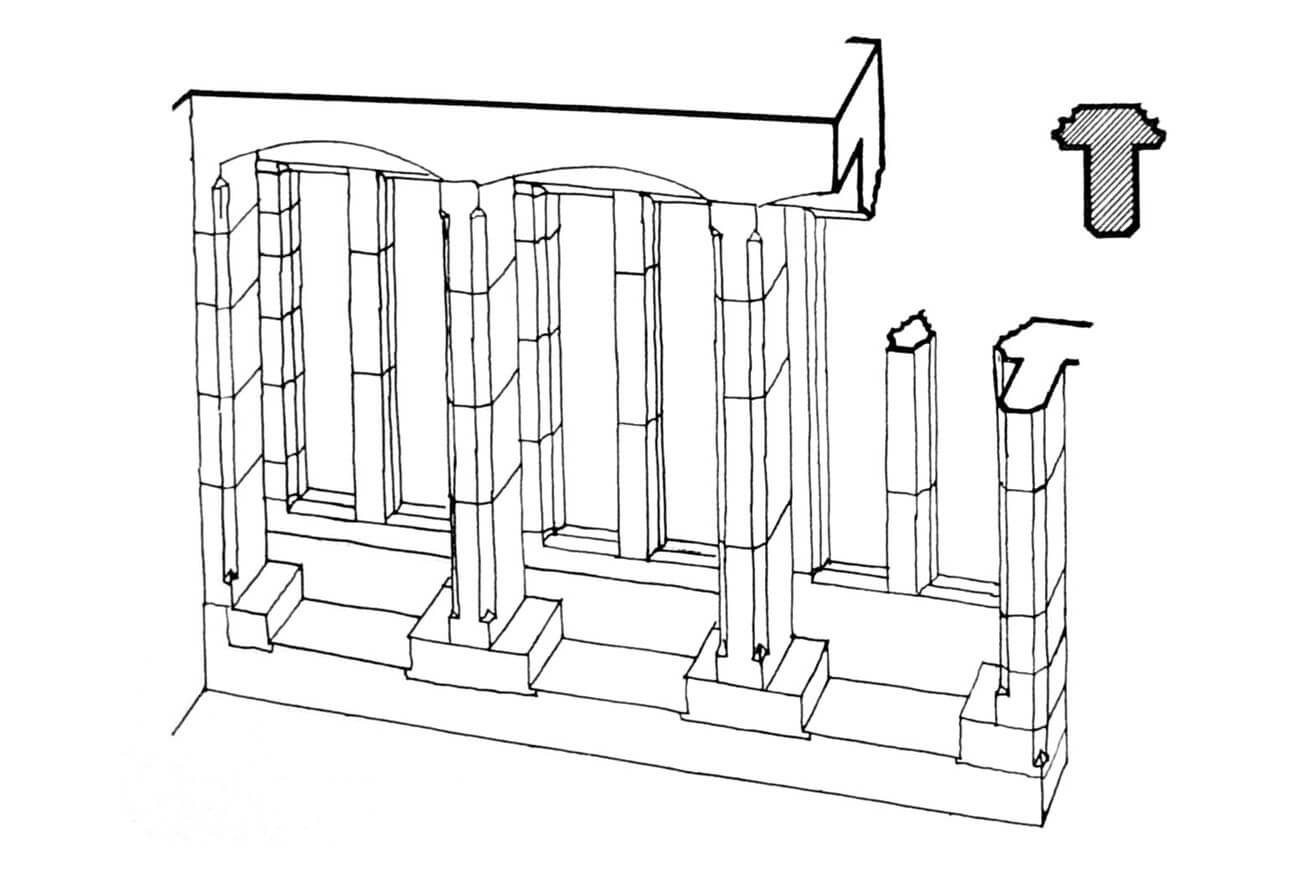

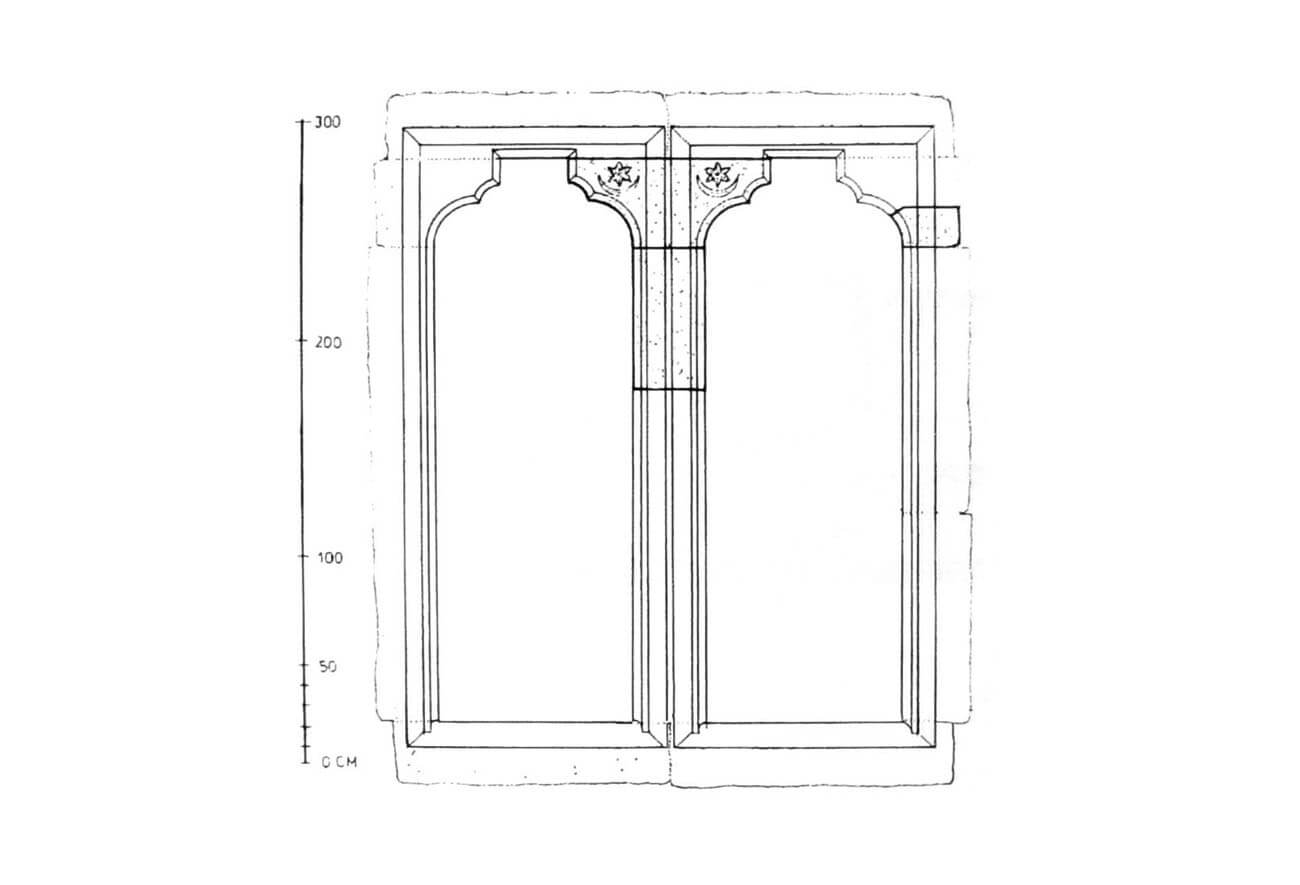

The most representative rooms of late Gothic tenement houses in Kraków, the rear halls on the ground floor level, were decorated with motifs inspired by sacral architecture, although they also developed autonomous patterns. Their longer walls were enlivened by single- or double-part arcade niches, usually semicircular, made of bricks with arches supported on stone corbels. These corbels were usually simple, sometimes decorated with figurative sculpture, but the whole, due to the precision of workmanship, took on a sophisticated and elegant expression. Arcades were also placed in passages, not only for decoration, but also for widening narrow spaces. Sometimes, instead of two arcades, a series of smaller ones were made, closed with segmental arches. The most decorative wall of the rear rooms on the ground floor were the walls facing the courtyard, where windows were placed in deep, segmental niches with usually stone frames, with moulding always facing inwards. Sedilia were usually placed under the windows. Until the end of the Middle Ages, the cover of the rear rooms was most often a wooden ceiling, because vaults in above-ground rooms were very rarely installed. Its beams were always placed parallel to the window wall and were usually covered with moulding. The rhythm of the beams, similarly to the arcades in the walls, created light and shadow effects. The walls were both plastered and left in a raw state, with careful grouting between the bricks. The plasters could be painted uniformly or with tracery, architectural or plant ornaments.

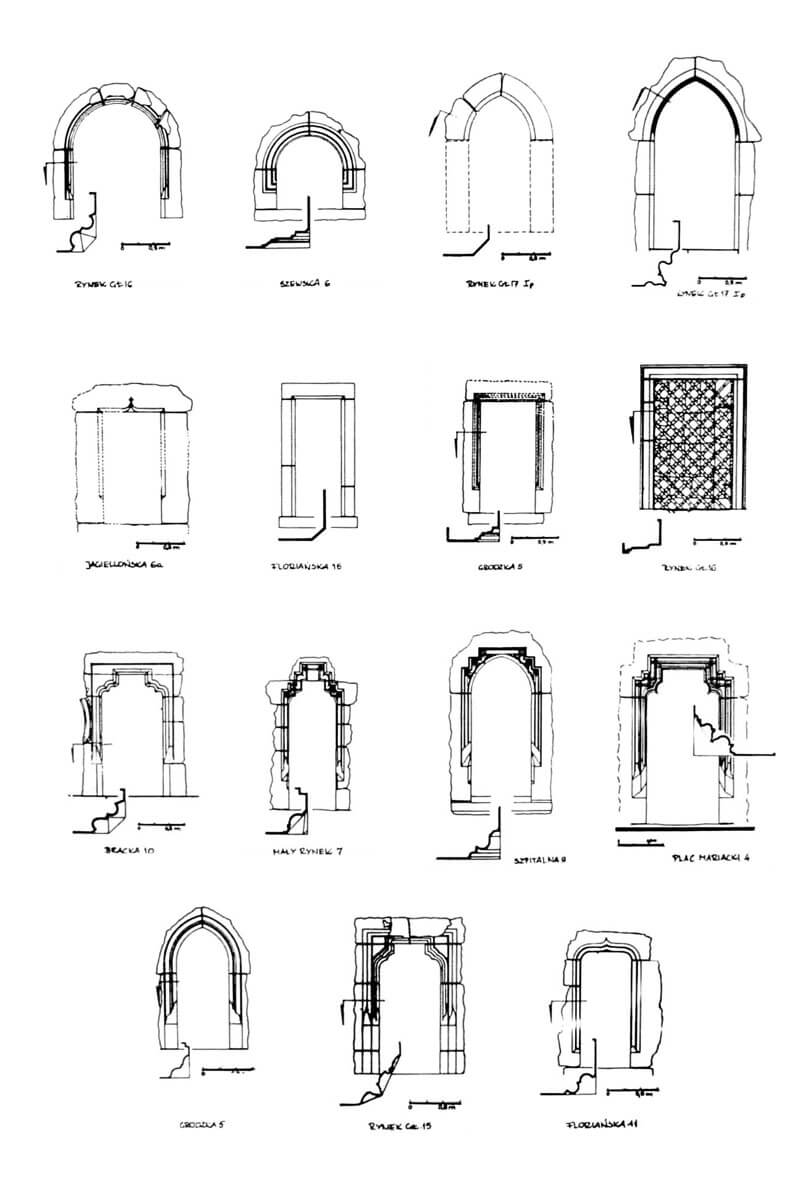

Portals in late Gothic tenement houses, probably due to their very large number even in a single building, usually had modest forms with simple or semicircular lintels. There were probably fewer pointed arches characteristic of Gothic, and the most sophisticated ones, chamfered and moulded, were of course placed in the most visible places. Post-classical Gothic brought an increase in the diversity of forms, thanks to the variously decorated, expressive in style, two-armed portals and ogee ach portals. Window frames were made of bricks and stones. They could have gentle pointed arches and embrasures, and even more often quadrangular shapes, often with extensive moulding. Moulding in the facades of late Gothic houses was directed outwards, while in the rear elevations (from the courtyards) towards the interior.

In the 15th century, some of the tenement houses at the market square and in the former Okół took on the form of impressive palaces, with those at the market square usually being the property of the patricians, and those closer to Wawel, of the knights and higher clergy. They were created by merging and expanding two neighbouring buildings, usually located on corner plots. Thanks to this, it had a significant cubic capacity, and also differed in their shapes and layouts. Their residents were part of or aspired to the highest levels of feudal society, which is why they adopted architectural solutions and the splendor known from buildings outside the city. It was particularly characteristic that on the first floors of Kraków palaces there were rooms modelled on castle great halls – the most spacious representative chambers. Called upper halls or palati, it were filled with very rich sculptural decorations and cross-rib vaults. Some, like the upper halls were equipped with chapel bay windows. In particularly impressive buildings, there was a tendency to create enclosed courtyards with cloisters.

The next residential buildings that stood out against the background of medieval Kraków were the canons’ houses in the southern part of the city, situated on the “platea Canonicorum”. In the second half of the 14th century, it were small one-storey structures with ground floors built of stone and upper floors of bricks. Initially, houses with a gable layout predominated. Those on deeper plots had side entrances, those standing on shallower properties, filling their entire width, probably had passageways. At the end of the 14th century, the canons’ houses were two-bay, relatively modest. In the first half of the 15th century it became larger and more comfortable. A significant change was the rejection of the gable roof form in favour of a ridge roof, with the gable facing the neighbouring building, thanks to which two long rows of continuous buildings were created along Kanoniczna Street. This was due to the wide form of the canons’ houses, which had to have a covering over the entire development. The facades of some canons’ houses in the second half of the 15th century were decorated with friezes consisting of pointed blind windows, as well as unusual shallow, rectangular niches, divided by crosses made of brick heads.

The roads in front of medieval tenement houses were successively covered with planks and dried with sand, ash or rubble, and their level was usually raised by waste and garbage. From the 14th century, more important streets were covered with stone pavement and wooden surfaces in the form of piers. Their construction began with driving vertical posts into the ground. On the posts, crosswise to the course of the street, girders were placed at distances of three or four meters. On them, joists were placed along the line of the street, and on the thus stabilized ground, planks of the surface were placed crosswise. The piers covered a strip of two to two and a half meters wide in the middle line of the street. It was similar in the market squares, where only selected communication routes were strengthened: around the square and between the stalls.

Current state

Virtually none of the medieval houses in Kraków have survived to the present day in their original form. In the remaining ones, various original elements are only partially visible, and the medieval walls are hidden under modern elevations. An exception is the house at today’s Świętego Krzyża Street 23, which probably dates back to the end of the 13th century or the beginning of the 14th century and may be the oldest residential building in Kraków preserved in such good condition, although it underwent extensive reconstruction work at the beginning of the 20th century. It was originally the seat of guards who kept watch at the neighbouring city walls. Later, it was inhabited by Benedictine nuns from Staniątki near Kraków, and then it became the seat of the Order of the Holy Spirit, after whose suppression the building was transformed into a rectory. A representative example of a tower house from the second half of the 13th century is the façade of part of the house of Mayor Henry at Bracka Street, with a preserved wide entrance opening and two high windows on the sides.

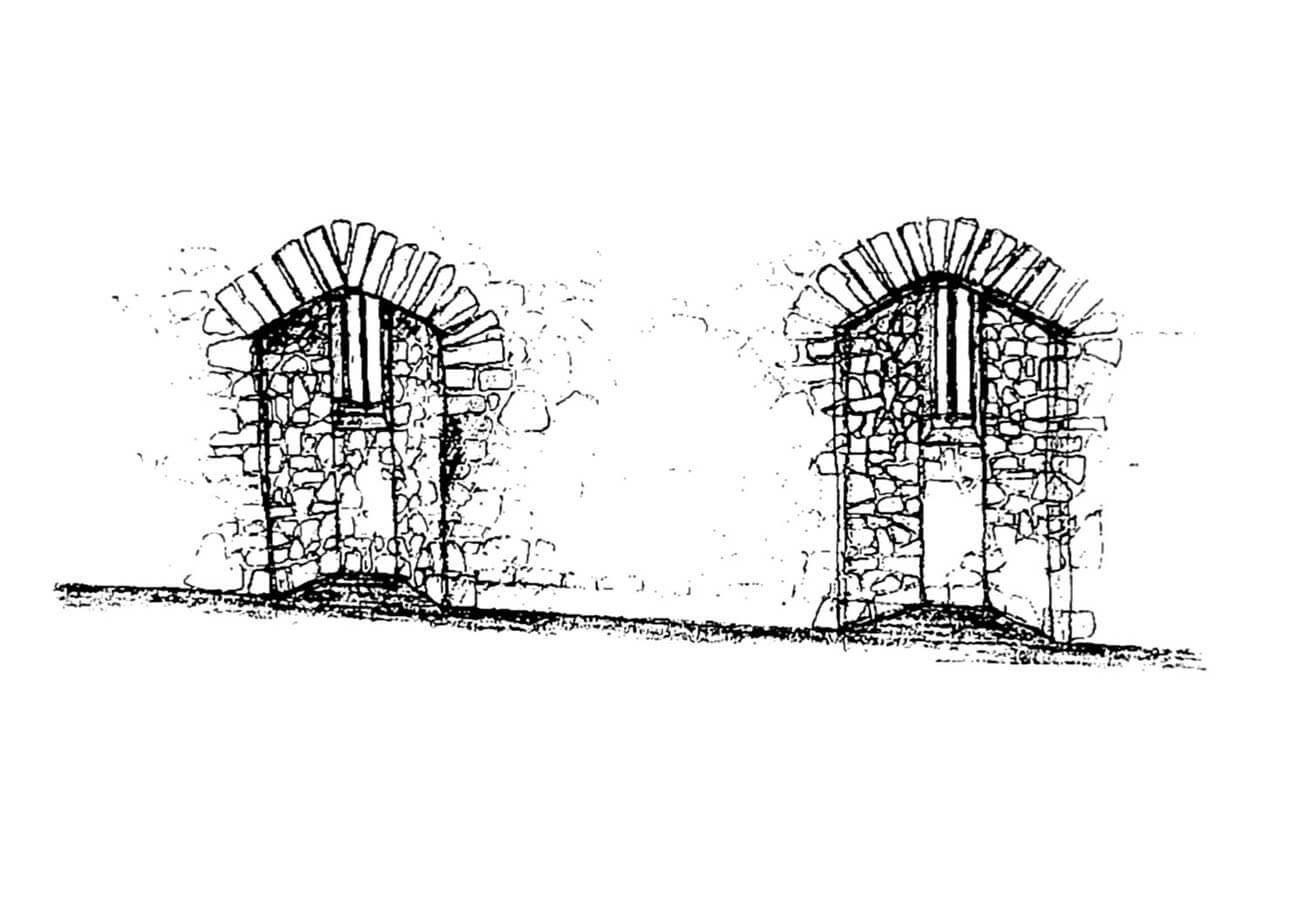

The facades of the 14th and 15th century tenement houses, although they have partially survived under modern plasters, are currently visible in very few places. At Szpitalna 8 Street you can see two storeys with windows, wall niches and a portal. Similarly, the elevation of two medieval storeys is visible at Mikołajska 14 Street, but without the original portal. However, both elevations are quite unusual, due to the large size of the ground floor windows, in which the owner abandoned the purely utilitarian arrangement of the interior, and in addition, the face of their walls was partially rebuilt. Untransformed, largely authentic brick facades are visible on the houses at Sienna 4 and 6 Street (but without the medieval window and door frames). The medieval portals can be seen, among others, on the facades of the houses at Floriańska 8 Street, Mariacki Square 8, and Św. Jana 9 Street. The window frames were removed and rebuilt more often, and they were also more exposed to weather conditions. Three bricked-up windows, perhaps from the 14th century, can be seen on the side elevation of the house at Szewska 11. A single late Gothic window from the 15th century has survived at św. Tomasza 31. On the external elevation of the house at Kanoniczna 7 Street, several windows from the early 16th century are visible. In addition, several blind windows and window jambs have survived on the elevation of the house at Kanoniczna 16.

Architectural details of Gothic interiors have been preserved, among others, in tenement houses at Rynek Główny 12, 15, 16, Sławkowska 9 and 26, Szpitalna 24, Szczepańska 9, Mikołajska 16. Impressive compositions of internal wall elevations have survived at Rynek Główny 17 and 26 and św. Jana 16. The building at Floriańska 3 contains the only example in Kraków of a combination of a triad of pointed arches with a semicircular niche. Numerous late Gothic portals have survived in the house at Rynek Główny 15, inside the tenement house at Bracka 10, Floriańska 41, Szpitalna 9 Street and Mariacki 4 Square. Medieval frames of windows, now bricked up, have been preserved on the third floor of the house at Rynek Główny 11. In the tenement house at Rynek Główny 23, in the eastern basement chamber there is a vault from the end of the 14th century, and at Rynek Główny 35 there is a vaulted interior of the stoop.

bibliography:

Firlet E., Opaliński P., Cracovia 3d, Via Regia – Kraków na szlaku handlowym w XIII-XVII wieku, Kraków 2011.

Jakimyszyn A., Cracovia Iudaeorum 3D, Kraków 2013.

Komorowski W., Kamienice i pałace rynku krakowskiego w średniowieczu, “Rocznik krakowski”, tom 68, 2002.

Komorowski W., Średniowieczne domy krakowskie (od lokacji miasta do połowy XVII wieku), Kraków 2014.

Komorowski W., Opaliński P., O wieży wójta krakowskiego raz jeszcze, „Czasopismo techniczne”, zeszyt 23, rok 108, Kraków 2011.

Łukacz M., Geneza ukształtowania się najczęściej realizowanego typu kamienicy krakowskiej, “Wiadomości Konserwatorskie”, 14/2003.

Łukacz M., Średniowieczne domy lokacyjnego Krakowa, “Czasopismo techniczne”, zeszyt 23, 2011.

Marek M., Cracovia 3d. Rekonstrukcje cyfrowe historycznej zabudowy Krakowa, Kraków 2013.

Opaliński P., Rekonstrukcja cyfrowa infrastruktury architektonicznej Rynku krakowskiego w XIV i XV wieku, “Krzysztofory”, nr 28, część 1, Kraków 2010.

Piekalski J., Praga, Wrocław i Kraków Przestrzeń publiczna i prywatna w czasach średniowiecznego przełomu, Wrocław 2014.