History

The Franciscans settled in Kraów in 1236 or 1237 and already in 1249 a provincial chapter was held in the friary. The original church was one of the first brick buildings in the city, because in 1269 the corpse of the Polish princess, a nun of Salomea Halicka, was moved to the chancel, and in 1279 the benefactor of the friary, Prince Bolesław the Chaste was buried in the chancel.

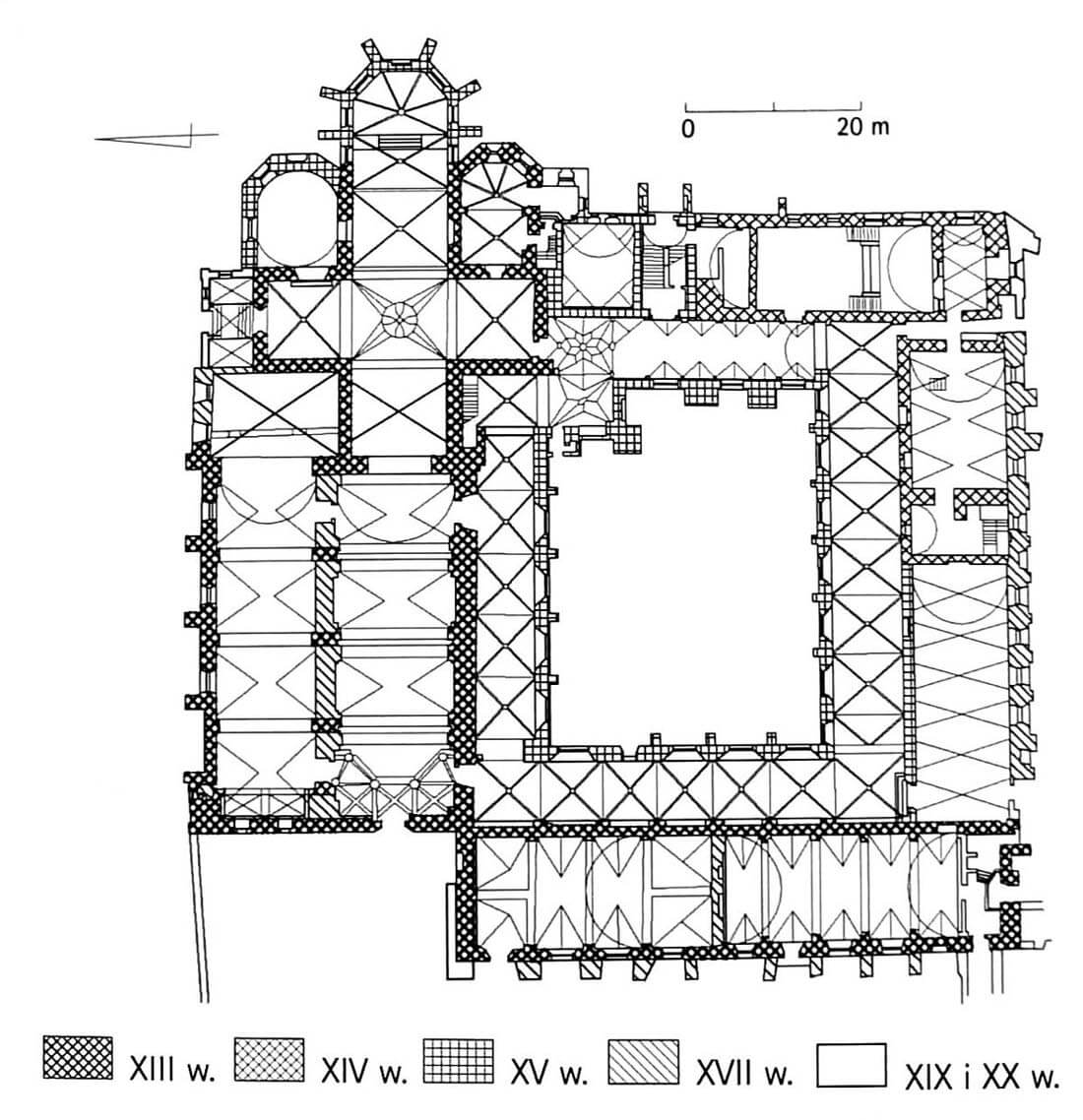

In 1277, the Franciscans obtained a new area from the Princess Kinga, which allowed for further expansion, carried out until the end of the 15th century. Indulgences given in order to obtain funds correlated with the progress of work. In 1309, the indulgence was granted by Cardinal Gentile, in 1379 the indulgence was granted for the payment of “pro fabrica ecclesiae sive reformatione chori”, and in 1423 the indulgence was granted “pro restauratione conventus ob varias calamitates ruinosi et defectuosi eiusdem ecclesiae”. Money was also from bequests and donations, for example, wills to the monastery were recorded in 1389 and 1400, in 1410 there was a legate of 100 fines for the construction of the choir, further “pro fabrica” were recorded in 1416, 1429, 1430, 1437, 1439, 1440 and 1443. The expanded friary church was re-consecrated in 1436 by Cardinal Zbigniew Oleśnicki, who, however, two years later granted another indulgence, repeated by the archbishop of Gniezno in 1441. Unfortunately, in 1462 the church was destroyed by a fire, in 1465 the tower collapsed and damaged the vaults, and in 1476 another fire took place.

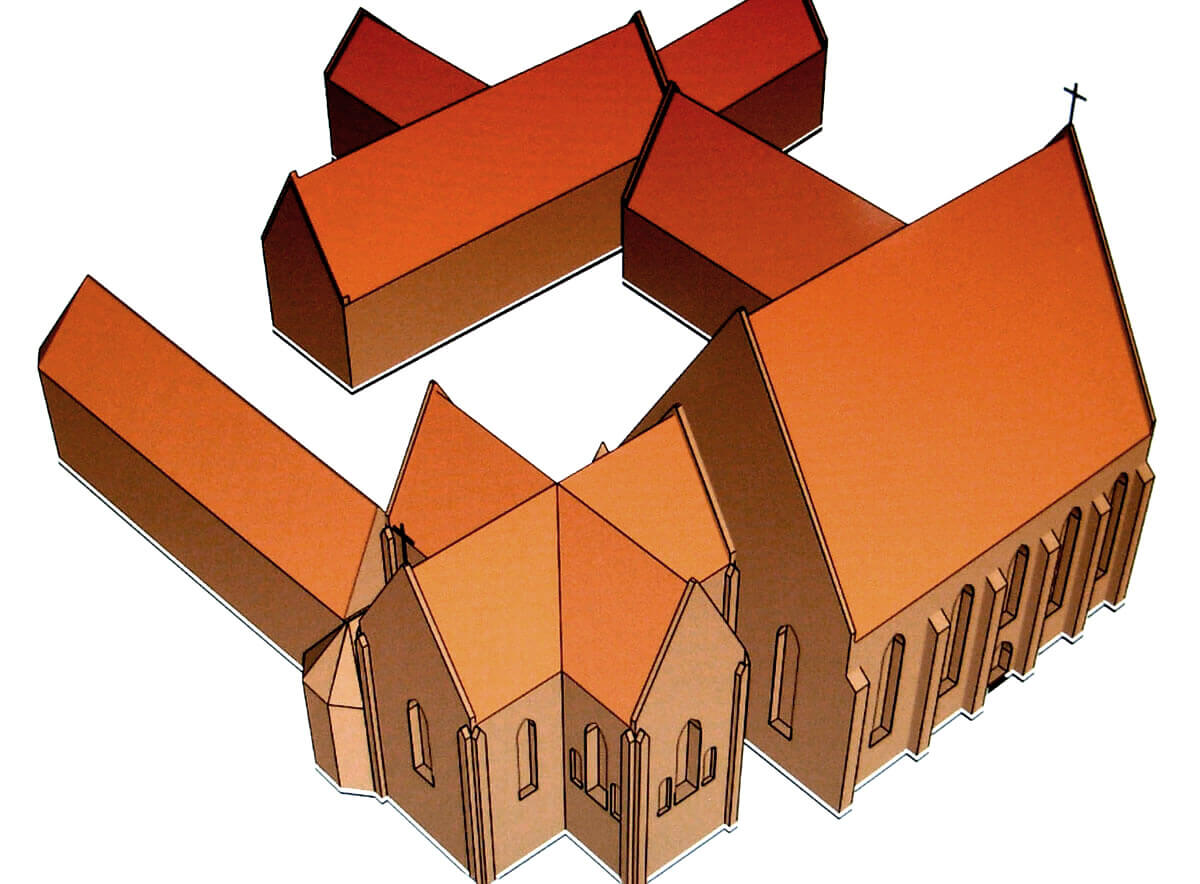

The early-modern architectural changes of the monastery began in 1563, when a bell tower was erected in front of the entrance to the church. In 1655 the church burned down once again. It was rebuilt by dividing the interior into the nave and the chapel made of the aisle, the façade of the church and the nave’s vaults were also transformed, and the roofs were lowered. The interiors were then decorated in a Baroque style. In 1677, it was re-consecrated. Then, in the years 1778 – 1782 and in 1835, the claustrum rooms were rebuilt, and in 1810 the chapel of St. Clara was slighted. The last and most destructive fire consumed the friary during the great fire of the city in 1850. It was followed by a neo-gothic reconstruction combined with the first architectural research. Renovations continued in 1905-1912 and 1964-1967.

Architecture

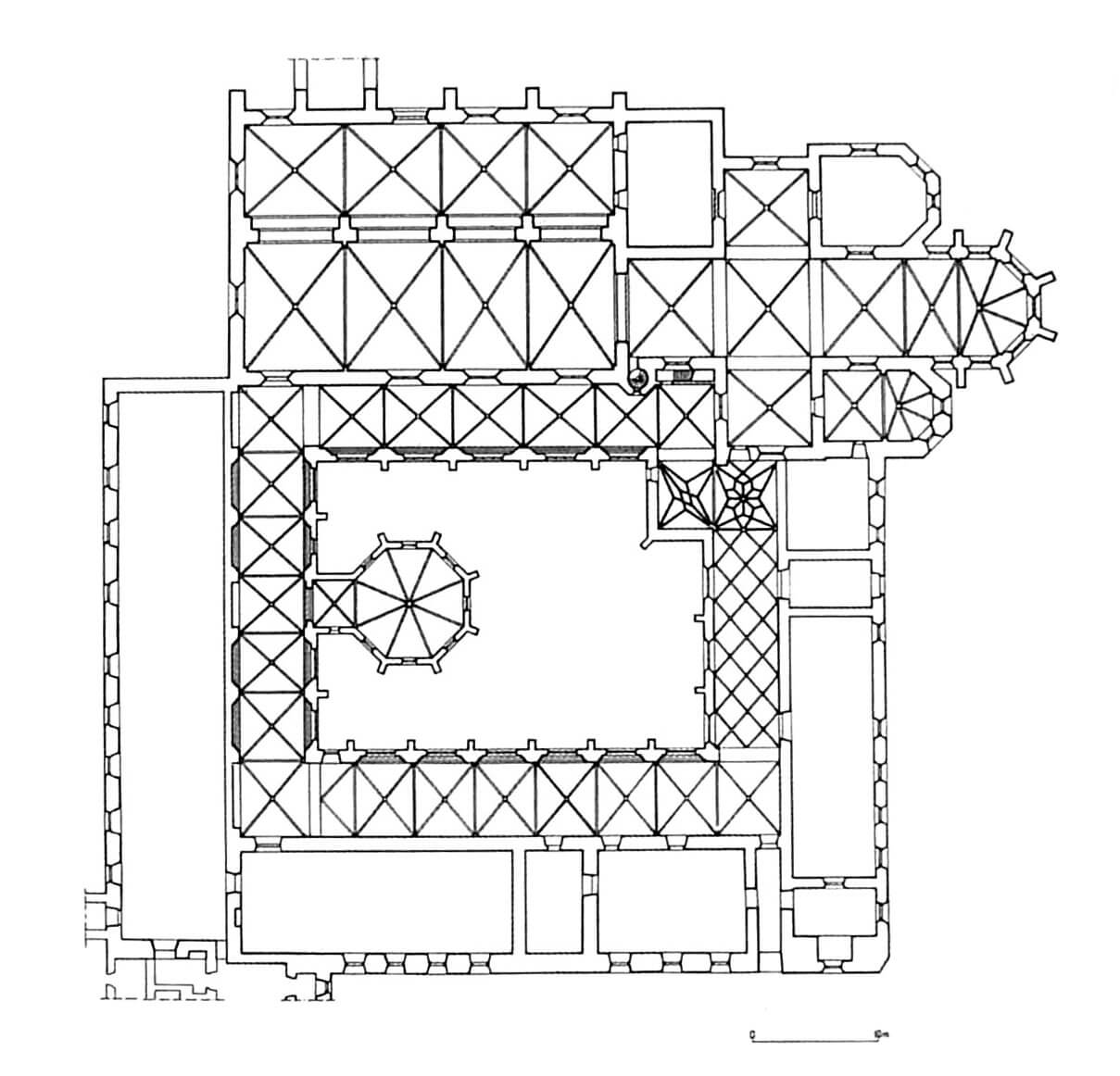

The friaryof the Franciscan monks was situated in the south-west part of Kraków, located between the city walls on the west and the church of All Saints in the east. From the south, initially the monastery was adjacent to the settlement of Okół near Wawel, in the 14th century incorporated into the city walls of Kraków. On the north side, Bracka Street was connected with the Old Town Square, opening onto the commercial buildings and the town hall. The northern part of the friary plot was occupied by the convent church, connected to the south with claustrum buildings, finally formed into three wings around the inner garth.

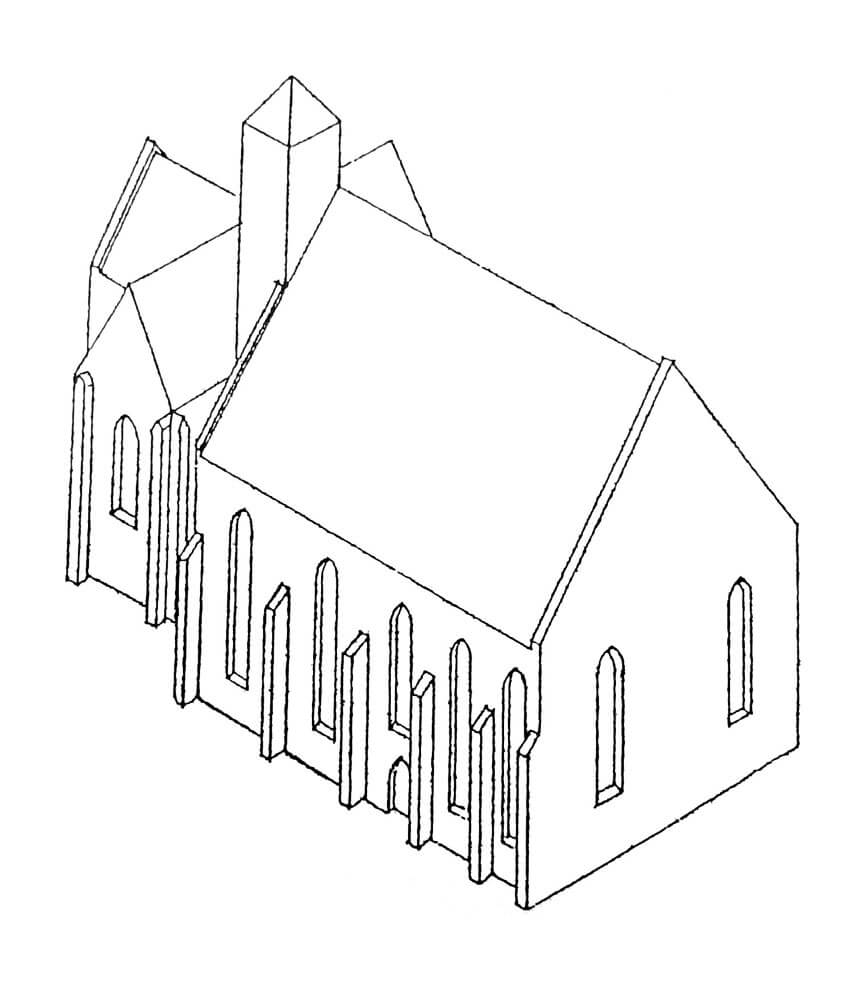

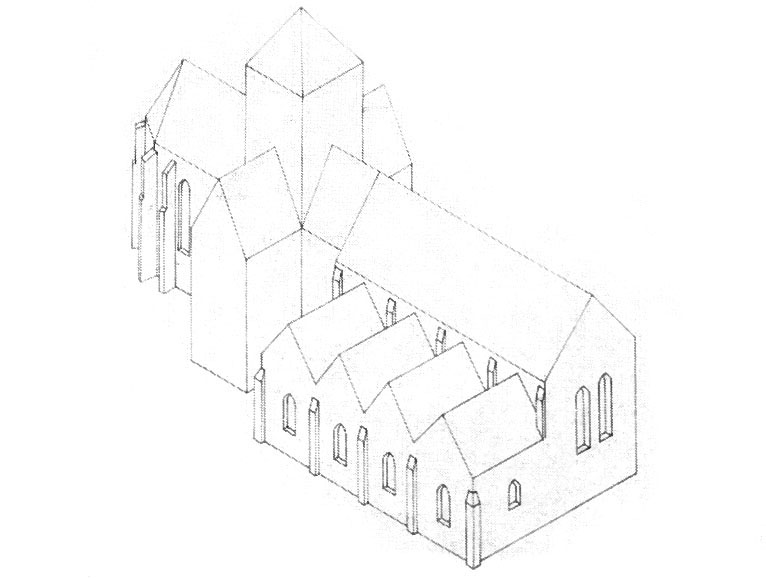

The original friary church from the 13th century was most likely an asymmetrical two-aisle, five-bay hall building with a chancel built on the plan of an isosceles Greek cross, most likely without a tower at the intersection of aisles. Perhaps it was an architectural borrowing from Italy, or maybe this shape originated from late antique and early Christian martyrs and mausoleums, because in the church was buried prince Bolesław the Chaste and his sister Salomea. Patterns closer to the cross shape of the chancel can be found in the parish church in Bolków and in the church in Kałkowo. The second aisle of the nave was built on the north side and had the same length as the main aisle, but was narrower. It can be assumed that this was connected with the attempt to create a double friary for the Franciscans and Poor Clares, but eventually the nuns gained their own separate buildings around 1320.

Originally, the bays on the façades of the nave were marked with windows and buttresses, in the interior with arcades on four pillars. Above, the hall was covered by a wooden ceiling or open roof truss. The chancel, on the other hand, consisted of square bays, vaulted and probably separated by arch bands. Around 1260-1270, a sacristy was added to the chancel on the south-east side, and a slender tower was located in the corner of the nave and the north-west side of the cross part of the church. In addition, on the opposite, southern side, at the junction of the chancel and the nave, a polygonal communication turret was placed. The elevations were set on a moulded plinth, supported by buttresses from the north. The interior was illuminated by two-light, splayed windows filled with traceries. The entrance led from the north through the central bay of the aisle and from the west.

The sacristy consisted of a square western bay and a polygonal closure in the east. Its interior was covered with a cross-rib vault over the western bay and a six-sided vault over the eastern bay. The lighting was provided by small windows with stone jambs, strongly splayed on both sides. Between the bays, semi-octagonal wall columns were placed, on which the ribs were supported, also supported at the corners and in the apse on corbels. The vault’s ribs were fastened with circular bosses decorated with reliefs.

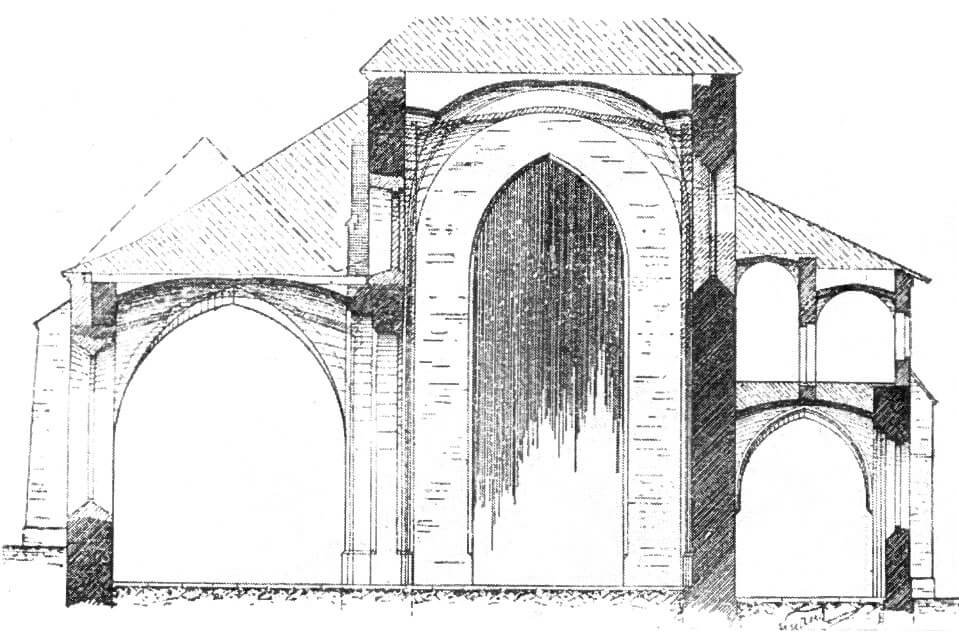

In the first half of the fifteenth century, the chancel was extended by two bays to the east, closed with a polygonal apse. This part was covered with a vault based on bundles of shafts supported on a cornice. From the outside, it was decorated with buttresses, a plinth, as well as drip and crowning cornices. The nave, however, after the destruction in 1465, was rebuilt in a new form, in the form of a two-aisle, asymmetrical basilica in a pillar-buttress system, with a narrower and lower northern aisle in relation to the southern aisle. Both these parts were separated by stone pillars on the projection of elongated rectangles, with buttresses on the north side. Chamfered inter-nave arcades were also created from the stone. The main aisle was covered with a rib vault based on polygonal shafts, and the northern aisle was also covered by the rib vault. Characteristically, after the reconstruction, the location of the windows no longer corresponded to the division into bays (they were not arranged symmetrically). The body of the late Gothic church was completed by chapels fitted between the arms of the eastern cross.

The friary buildings originally consisted of a house whose north-east corner connected with the south-west corner of the church nave. This building took the place of an older house, made of limestone before the arrival of the Franciscans. The second pre-Franciscan building with a plan similar to a square with sides length of 18 meters, perhaps a tower-like building, was in the place of a later gate, on the south-west side of the enclosure. Then a free-standing hall, orientated towards the parts of the world, was erected (later the chapel of St. Eligius in the southern wing of the enclosure), and only then, unusual, the eastern wing, considered to be the most important in the monasteries.

The oldest west wing was originally a one-story building, erected on a rectangular plan, divided inside into two large rooms: northern and southern, both of which were covered with flat ceilings. The rooms were accessible from separate entrances from the east, and they were illuminated by semi-circularly topped windows placed in splayed jambs and filled with traceries. Windows consisted of three stone, lancet arcades with a circular moulding (a motif typical of 13th-century English architecture, but also found in German countries). The function of both rooms is unknown, but it is assumed that at least one of them, southern one, served as a refectory with a niche for the reader wgo read during meals. The second hall, the northern one, was equipped with benches circling the entire interior, so it is seen in either the chapter house or the second summer refectory, although the functioning of two refectories at such an early stage, with a not very extensive convent, seems unlikely. Also placing stone benches by the walls would be more suited to the chapter house than the dining room, where meals were most often eaten on wooden tables in the middle of the room.

Initially in the southern range there was a free-standing chapel with internal dimensions of 7.8 x 12.7 meters. Its walls were built of bricks laid in the monk bond, but the architectural elements (portal, window jambs, traceries) were made of stone. It was accessible by a portal from the north. From the eastern side, the friary was initially opened, or rather secured with some kind of fence or wooden buildings. The regular, rectangular eastern range was not erected until the 15th century, then it was connected with cloisters with the southern and western wings, as well as with the church. On the west and south sides of the monastery complex, there were two utility yards, limited by the line of city fortifications.

At the beginning of the 15th century, friary cloisters were built, which connected the older, symmetrically located but scattered buildings into a classic arrangement of a three-wing claustrum, adjacent to the church and separating an open garth inside. The three arms of the cloisters were covered with cross-rib vaults, and the eastern part, unusually bent due to the need to adapt to the shape of the church, with a net and stellar vault. The ribs of the cross vaults were springing from stone, moulded, pyramidal corbels and corbels with men’s heads and plant decorations. They were fastened with bas-relief bosses, among others in the form of a man’s head and the head of Christ. Illumination of the cloisters was provided by a three-light windows in stepped frames. In the western part of the garth an octagonal chapel of St. Clara was built, supported by buttresses, covered with rib vault, with a single-bay passage on the west side connecting with the cloister.

Current state

Although the Franciscan convent was destroyed by fires and rebuilt many times to our times, it has preserved in its Gothic and partly neo-Gothic form. In the friary cloisters have survived the Gothic frescoes, and the gallery of Cracow bishops painted in the 15th century. The layout of the original friary church is best visible today in the chancel part, forming the plan of the Greek cross, adjacent to the south, a slightly later sacristy, and in the southern wall of the nave, in which there are the remains of five pointed windows.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Bober M., Architektura przedromańska i romańska w Krakowie. Badania i interpretacje, Rzeszów 2008.

Goras M., Zaginione gotyckie kościoły Krakowa, Kraków 2003.

Krasnowolski B., Leksykon zabytków architektury Małopolski, Warszawa 2013.

Szyma M., Datowanie i pierwotna funkcja zachodniego skrzydła klasztoru franciszkanόw w Krakowie [w:] Żeby wiedzieć. Studia dedykowane Helenie Małkiewiczównie, Kraków 2008.

Walczak M., Kościoły gotyckie w Polsce, Kraków 2015.