History

At the beginning of the 13th century, Kamieniec together with the surrounding villages belonged to the mighty Pogorzel family, who in 1210 founded the Augustinian provostry in it. Wincenty from Pogorzela, who was previously a monk in the Na Piasku abbey in Wrocław, was its first provost. Along with other monks, he separated from his mother monastery and came to Kamieniec, wishing to follow the order’s rule more closely. In 1230, Prince Henry the Bearded gave Augustians to develop 150 fiefs of forest, located in the area of the cutting, in which several villages grew. However, the development of the provostry was closely related to Wincenty from Pogorzela. When in 1243 he became an abbot in the Na Piasku abbey, in a short period the Kamieniec fall. For this reason, four years later, Wrocław’s bishop Thomas I gave Kamieniec Ząbkowicki to Cistercians from Lubiąż. Admittedly, the Augustians tried to defend their property by addressing the Pope, but in 1251 Innocent IV approved the Kamieniec land acquisition and its perpetual possession by the Cistercians. Soon, they began building of the church and monastery buildings according to their own rule.

At the end of the 13th century, a dozen or so villages belonged to monastery goods, and up to 80 monks lived in the abbey. Along with the monastery, the settlement began to develop, which in a short time the Cistercians imposed tithes and created a farm on its territory. The Cistercians ran agricultural activities, which were supported by the good quality of soils in the area of the Nysa Kłodzka Valley, as well as cattle, horses and sheep breeding. The ponds provided the fish, and apiaries of honey, Cistercians also dealt with weaving, tailoring, tanning, shoemaking, bakery, brewing and distillery. These products met the needs of the monastery, the population of the monastery villages, it were also sold at the fairs. There were monastery forges too. The milling was another branch of industry. The monastery mills mainly processed grain from farms belonging to the abbey, but sometimes other people used them. The Cistercians started to build water mills, as one of the first in Lower Silesia. One of mills was within the monastery. It was driven by water from a specially conducted canal called Młynówka. Cistercian monks had still mills in the neighboring villages, but the most interesting one belonged to the abbey, bought in 1326, was a mill floating on rafts or barges, which could be moved anywhere in the river. In 1273, prince Henry IV Probus gave the monks the right to minerals and deposits extracted in the areas belonging to the abbey. The exemption from taxes for the prince, which the monks continued to gain, contributed to the improvement of the monastery’s wealth. In 1356, the prince of Ziębice, Nicholas, freed Cistercians from Kamieniec completely from such services.

The monastery was a political force that was important in the Middle Ages. The abbey played the role of a mediator in the conflict of the bishop of Wrocław, Tomas Zaremba, with Henry IV Probus. The monks supported the ruler’s unified plans and supported him in his quest to reach the crown. The Czech king Wenceslaus II also sought their favor. As a result, the important donation of the town of Międzylesie, together with the adjacent areas, was handed over to the abbey in 1294. It is known that in the abbey at least from the end of the 13th century there was a scriptorium, in which the Antiphonary of Kamieniec was created, with the oldest in Silesia fully Gothic decoration.

The location of the abbey in the backwaters of Nysa Kłodzka exposed it to constant floods, the first of which was registered in 1359. Despite this, the fourteenth century was a period of prosperity for the abbey. At that time, the Cistercians of Kamieniec obtained numerous privileges from the rulers, developed craft activities and derived income from trade. They also incorporated the majority of patron churches, obtaining a significant income from them.

Period of prosperity ended in the fifteenth century, when the abbey twice, in 1426 and 1428, was invaded by the Hussites, then the Hungarians, and subsequent destruction were caused by floods that occurred in 1496 and 1501. As a result of these invasions, not only monastic goods, but also the community itself suffered. The number of monks decreased from around eighty in 1359 to around sixty in 1426 and only fourteen in 1463. In 1524, the Kamieniec monastery suffered due to a large fire, which destroyed some buildings and delayed the renovation works.

The next period in which the abbey fell into decline was the Thirty Years War. The abbey and its properties were devastated and plundered by armies. In addition, the monks were forced to lodge Saxon troops, as well as to pay money for the construction of trenches and fortifications near Bardo. Additionally, in 1633, the plague broke out and hunger prevailed because of high prices.

The abbot Simon III Rudiger, who arrived from Lubiąż, rebuilt the monastery goods and spiritual life. In the second half of the 17th century the church was renovated and a comprehensive rebuilding of the Baroque abbey began. A new brewery, bakery, tavern and grange were also established, and a monastery library was created. Simon‘s successors: Frederick Steiner, Augustine Neudeck, and Gerard Woywoda continued reconstruction and rebuilding. The period of prosperity ended with the advent of the Silesian Wars. The high taxed monastery began falling into debt, almost reaching bankruptcy. In addition, the functioning was difficult because of the Habsburgs interference to the religious life and the selection of abbots. In 1807, the Napoleonic army was stationed in Kamieniec, furthermore charging the monastery. In 1810, the Prussian king Frederick William III issued a secular edict that liquidated the abbey. The monks were sent to work in diocesan parishes, and the monastic goods were dispersed and devastated. In 1817 a fire broke out in the monastery, as a result of which some of the rooms were destroyed. During World War II, the monastery and church were the largest storehouse of art and archives in Silesia. Since the end of the war, the post-Cistercian temple has been a parish church. In the surviving buildings of the monastery, a branch of the State Archives was established, and in the economic facilities a breeding center.

Architecture

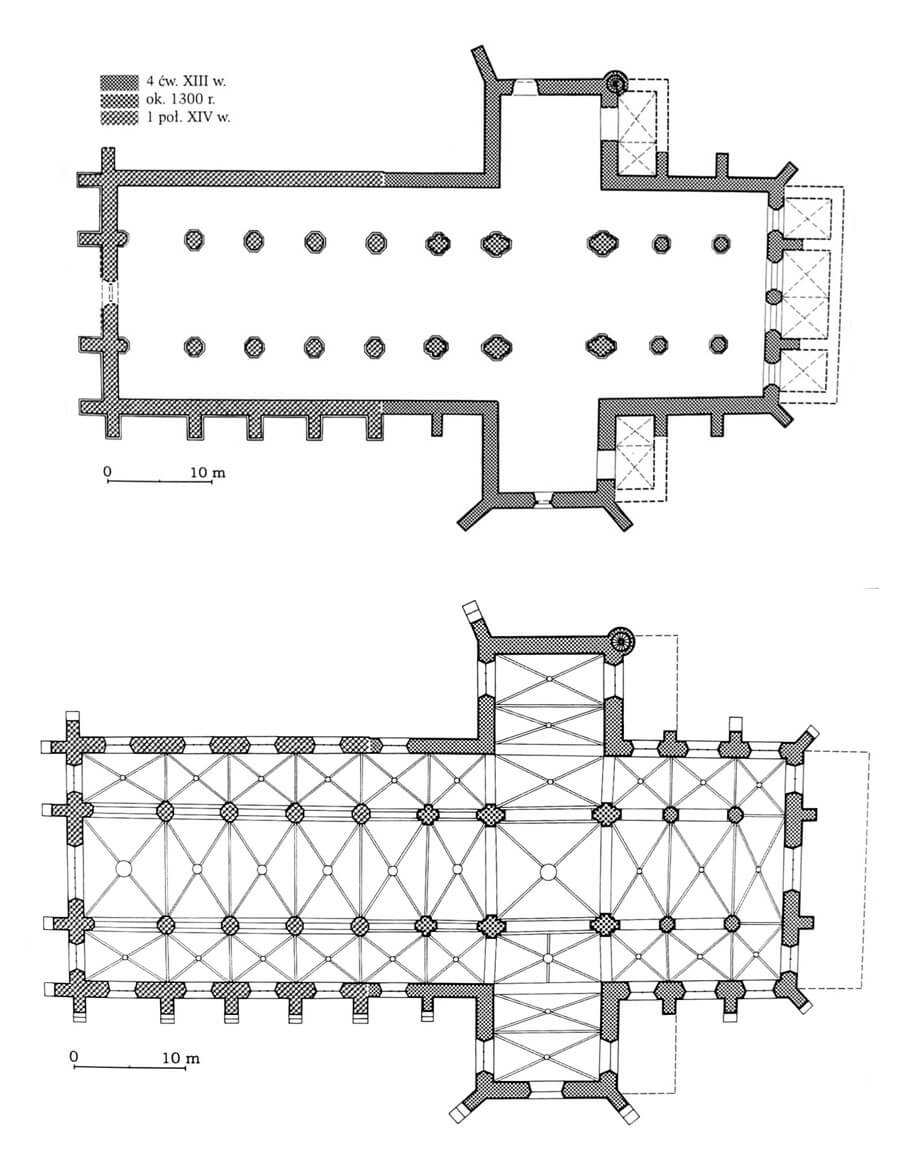

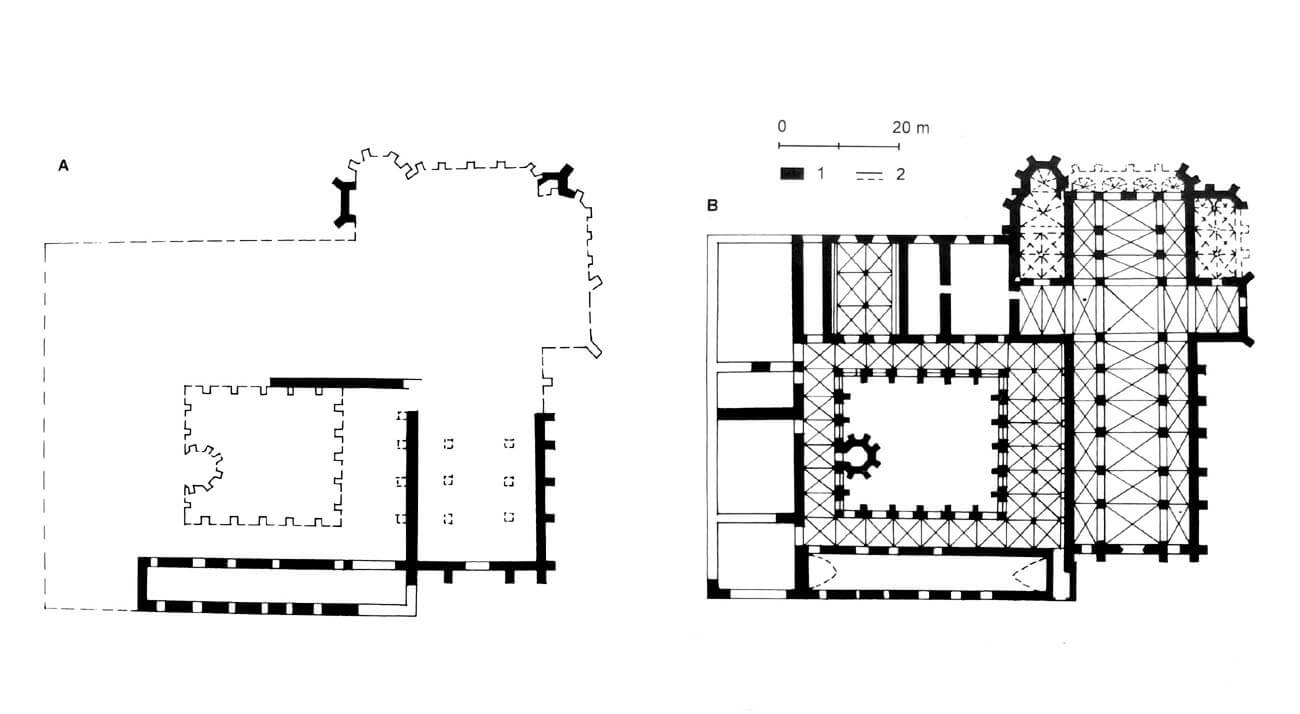

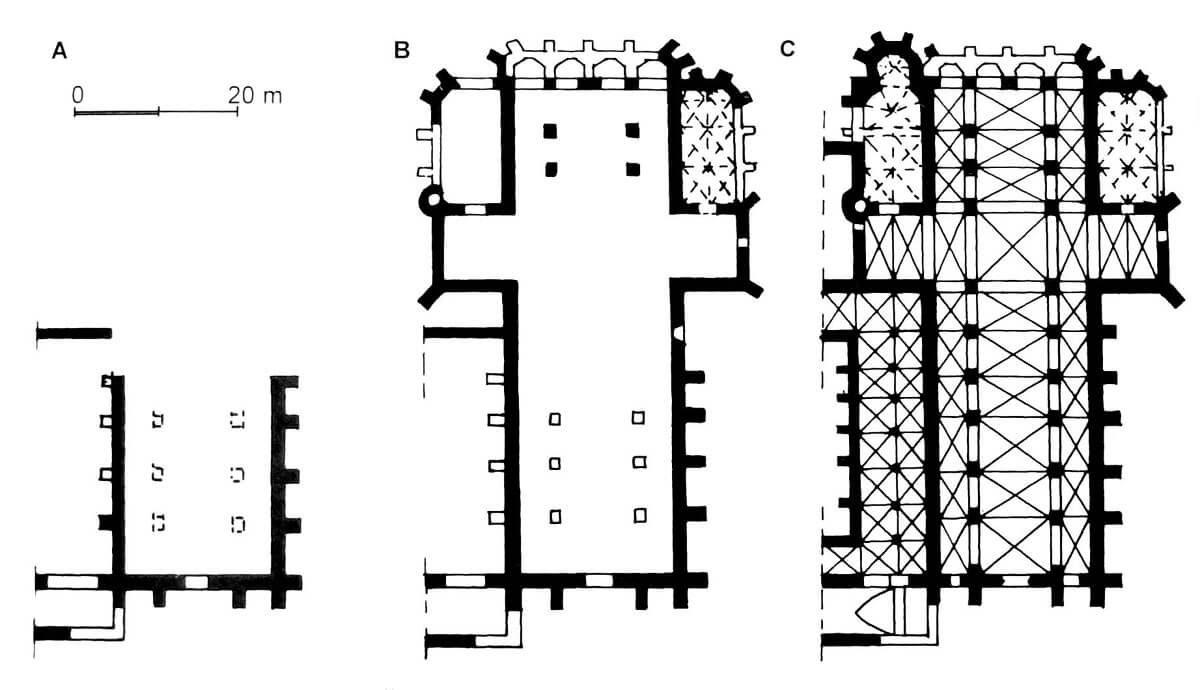

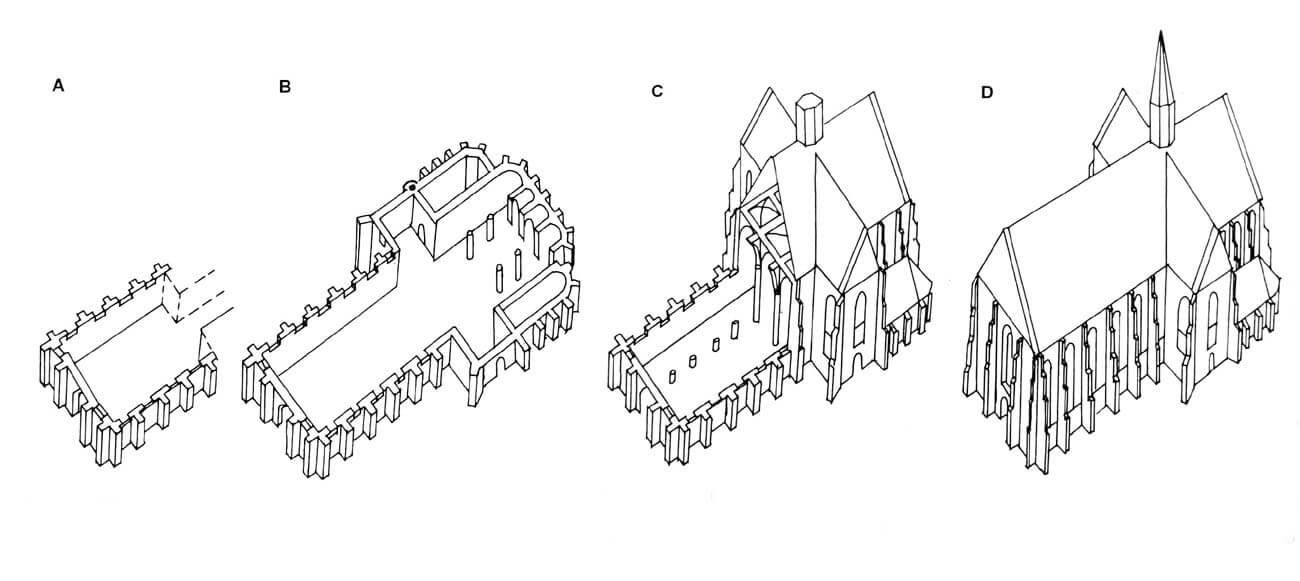

The abbey was founded in the Nysa Kłodzka valley, at the mouth of the Budzówka and near the mill canal, at the foot of the Bardzkie Mountains. It was built on the foundations of the Augustinian monastery and probably therefore had a different layout from the other Cistercian abbeys, namely the monastery buildings were located on the northern and not southern side of the church. During the construction of the abbey, the Cistercians probably used the earlier walls erected by the Augustinians, who, modeling on the mother monastery in Wrocław, planned to erect a three-aisle church with a separate western part, perhaps equipped with towers. They managed to build only the perimeter walls of the three western bays of the nave to a height of about 4 meters, later distinguished by the height of the pedestal from the walls built by the Cistercians.

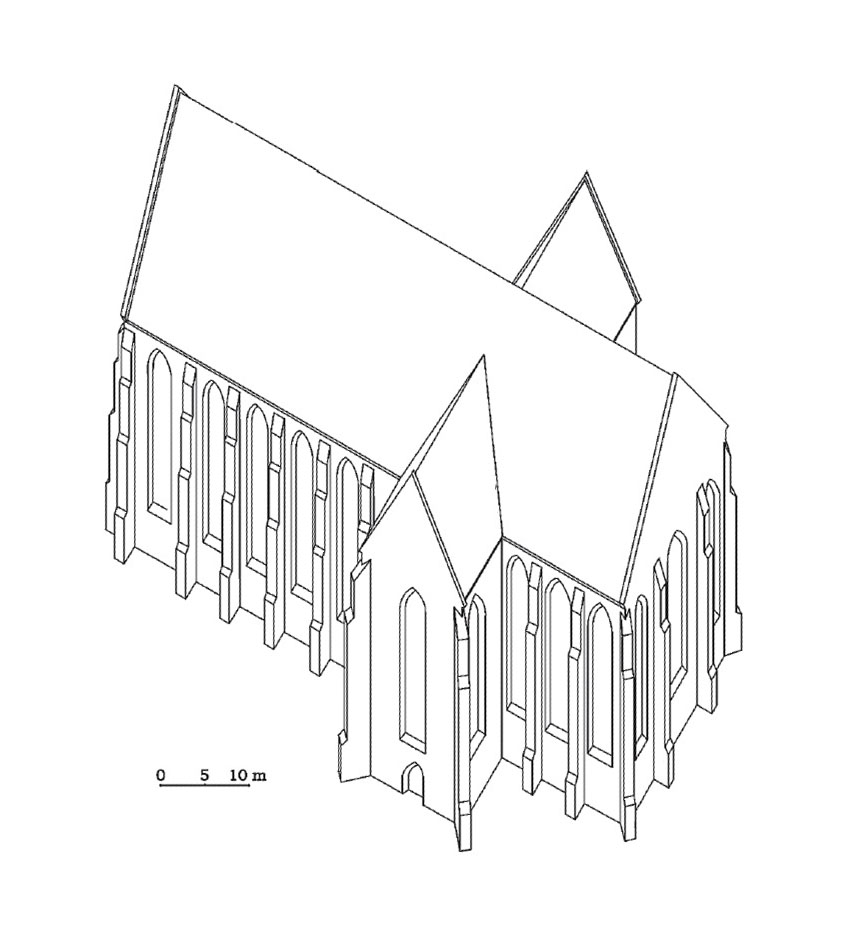

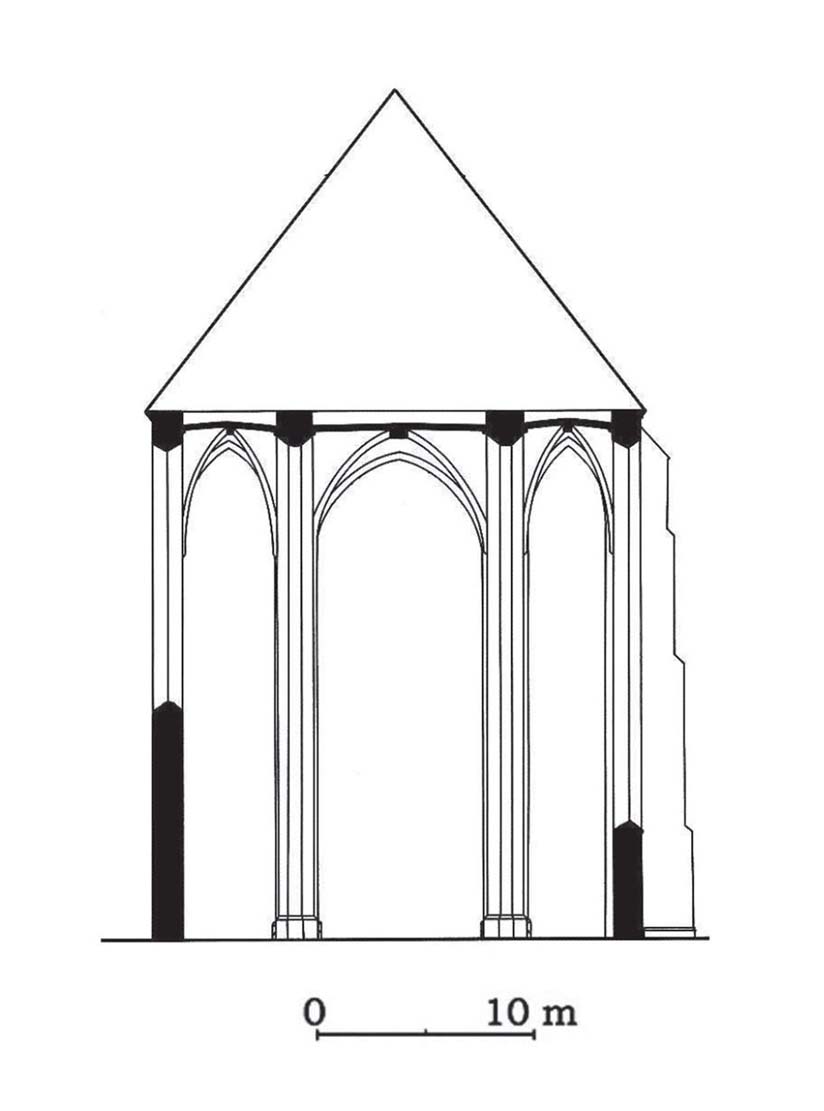

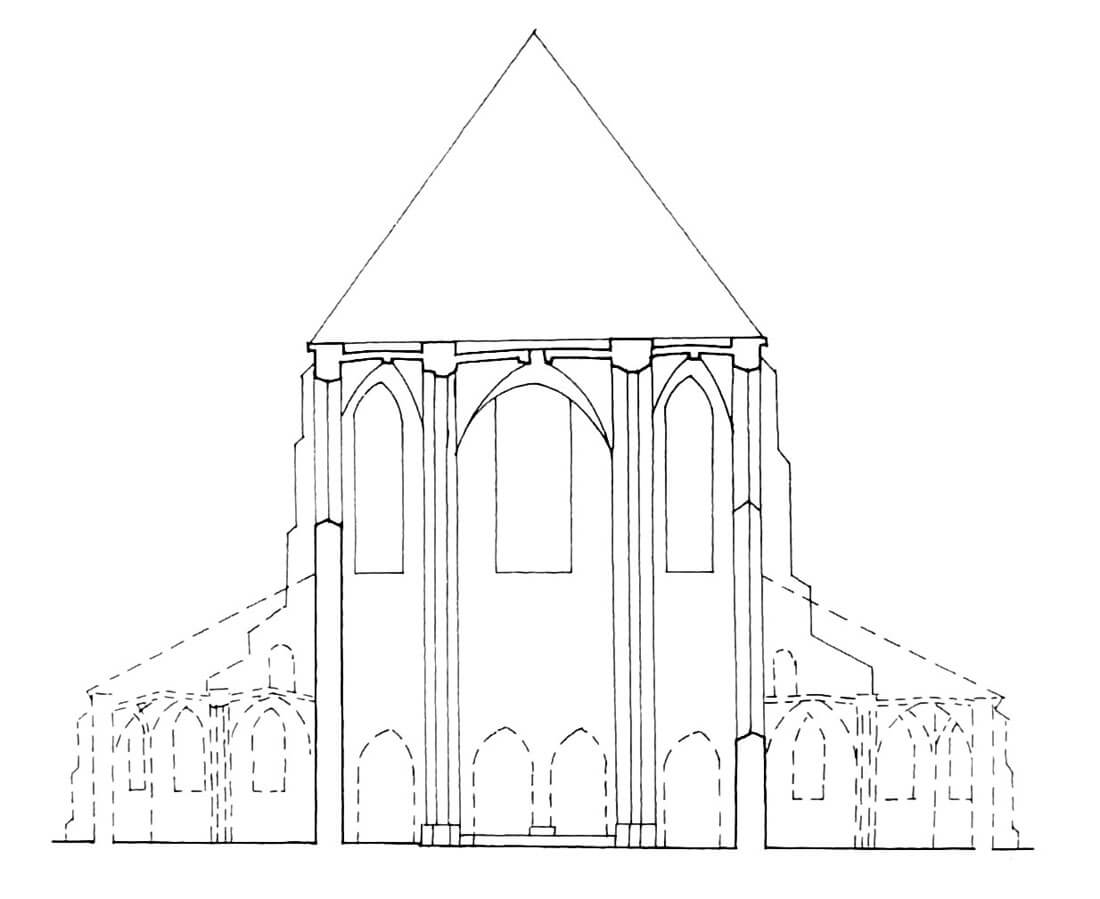

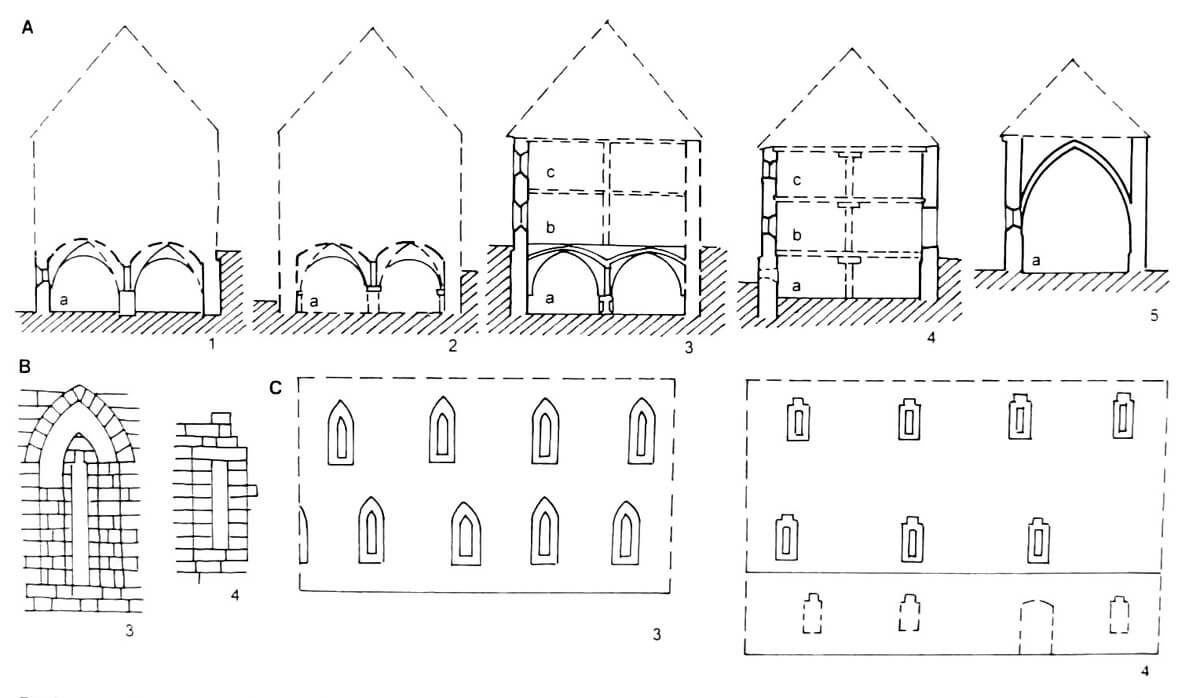

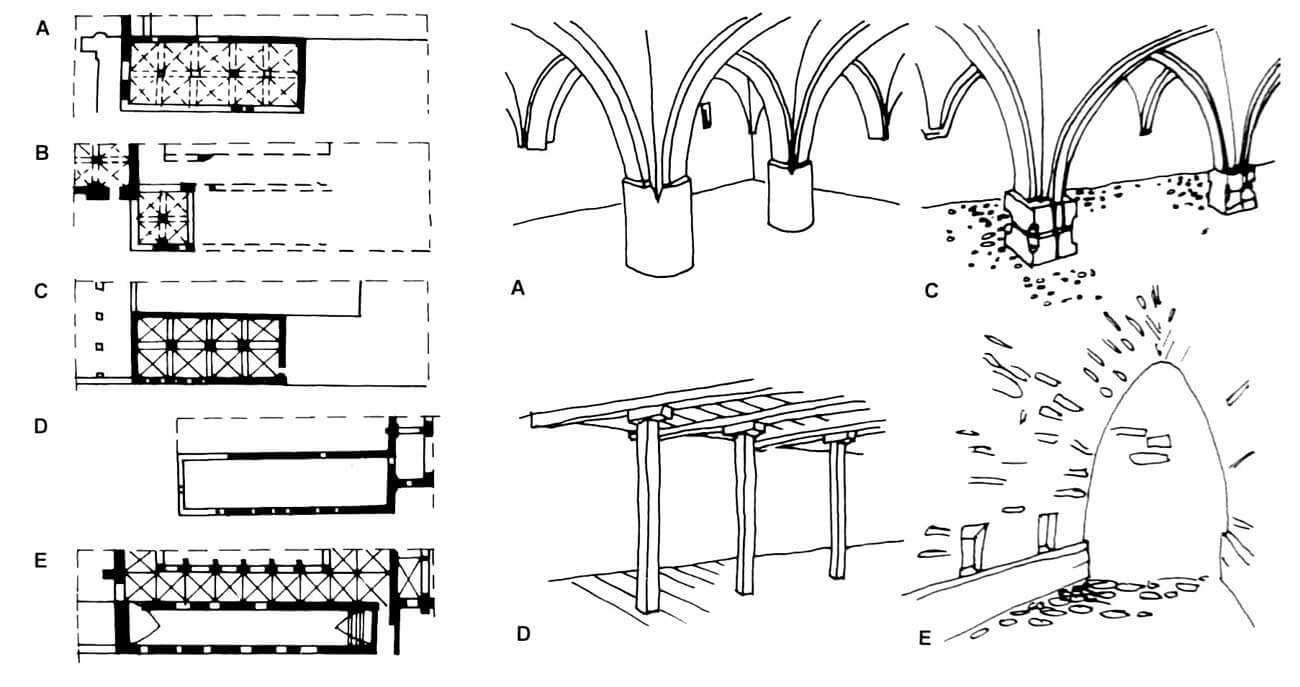

The Cistercian church was erected atypically as a hall building, not a basilica, three-aisle building with a transept and chancel ended with a straight wall equipped with side chapels on the north and south sides of the chancel, accessible only from the transept. The decision to build a church in the form of a hall had to be made at the end of the 13th century. Undertaking such a large construction effort must have been associated with the growing income of the abbey and the period of its prosperity in the fourteenth century. In the first stage, the upper fragments of the walls of the eastern part were built, windowsills were raised, and pillars with richly moulded bases were inserted between the chancel and the ambulatory. The introduction of the ribs of the vaults was done in a sophisticated and complicated way, because the shaft of the column with an octagon cross-section narrows, and the rib arches come out directly from column into the shape of palm leaves. Cross-ribbed vaults of the chancel were also than built. After 1315, pillars were built in the transept and the first bay of the nave. Unlike earlier supports, the transept columns were given a uniform cross-section over their entire height and did not narrow. In the last stage, probably until the mid-fourteenth century, using the Augustian walls, the western bays of the nave were built, with another change in the form of architectural detail. Namely, the vaults were supported on columns with an isosceles octagonal cross-section as opposed to earlier columns on a cross plan, and the introduction of the ribs was maximally simplified in terms of technology (they are as if stuck to vault coverings).

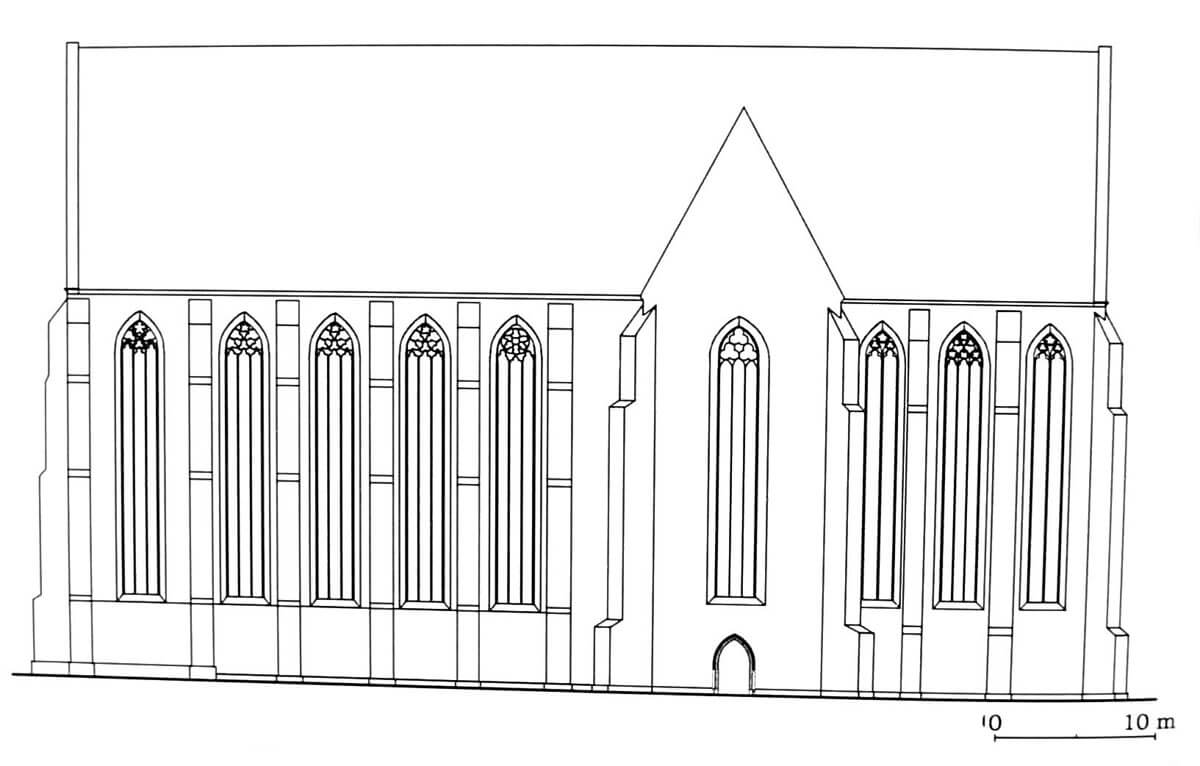

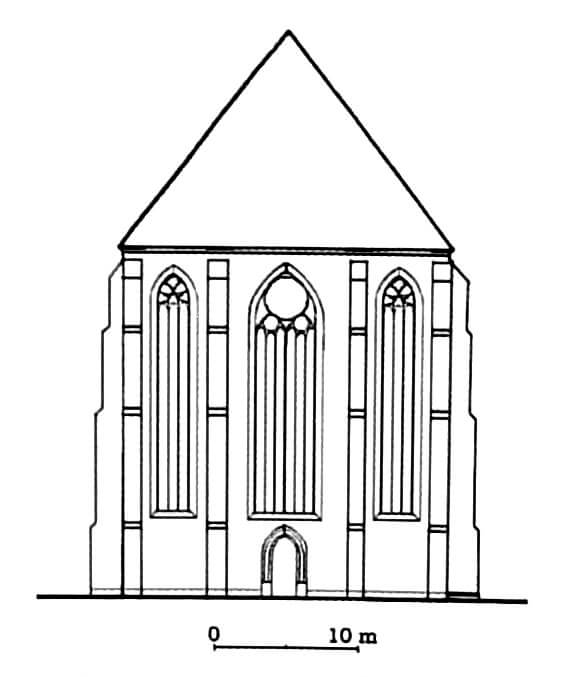

Finally, the church reached 70 meters long (chancel 16.3 meters, nave 36.3 meters, transept 9.1 meters), 20 meters wide, 24 meters high, and the length of the transept 37,7 meters. The aisles received the same height over their entire length. The whole building, except the northern wall of the nave and transept, was reinforced with high buttresses, between which large ogival windows were pierced. The church was topped with gable roofs, and originally the nave, chancel and transept walls were crowned with Gothic gables. In the eastern wall originally there were four arcades leading to three chapels, the chapel and sacristy were also on the sides of the chancel, at the eastern walls of the transept. The entrance to the church was located from the west and in the arms of the transept, from the south and from the north from the monastery.

The construction of enclosure buildings was probably completed at the beginning of the 15th century. During this period it was made up of three wings with a square patio in the middle. To facilitate communication, buttressed cloisters were erected around the latter, of which the southern one, which was rare, was two-aisle. It was part of the cloister adjacent to the church, and therefore considered as a spiritual zone. There were community meetings and evening reading of prayers, which is why wall seats could be placed there. The increase in the width of the southern part of the cloister in Kamieniec could also have been associated with the weekly mandatum ceremony, during which the monks were washing each other’s feet as a sign of humility. For a change, the eastern part of the cloister was associated with the intellectual aspect, because this part was adjacent to the rooms with books and the chapter house. Thanks to the openings in the chapter house, lay brothers and novices standing in the cloister could listen to the proceedings taking place inside. The northern part of the cloister was associated with bodily aspect due to its proximity to the refectory. From its central part one could go to the octagonal cover of the well surrounded by buttresses, probably topped with a pyramidal roof, where the brothers could wash before a meal. The arcades of the whole cloister were not open to the patio, but already in the Middle Ages they were filled with glazing mounted between lead bars. What’s more, every window sill had a small niche in the interior with an opening to drain water out.

The narrow west wing, erected by the Augustinians, was probably originally two-storey, with a two-room cellar at the bottom below. To the north of it was a room, perhaps originally serving as a lay brothers refectory, and at the upper floor there was a lay brothers dormitory, initially perhaps separated by low partitions between mattresses, and later wooden walls separating individual sleeping cells. The windows most often had a slit form to maintain a tolerable temperature inside unheated rooms. At the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, due to the decline in the importance of lay brothers institutions, in the west wing a high chamber was constructed, covered with a common tunnel barrel vault, thus transforming the entire building into an impressive warehouse.

The sacristy was located in the east wing at the transept of the church. Then there was the abbot’s chapel (or parlour, a place where monks could talk without fear of breaking their vow of silence) and behind it a two-aisle and three-bay chapter house, covered with a rib vault supported on two columns. It was probably the most elaborately decorated hall in the abbey, because its function was the daily gatherings of monks under the abbot’s leadership, during which, sitting on the stone benches along the stone walls, the most important issues regarding the community were held and the vicious monks were judged. In Cistercian monasteries, chapter houses also often served as the burial place of abbots. Most often, above them and the entire eastern wings were dormitories, accessible via a staircase from the cloister side, connected to the church transept to allow go to night prayers and with latrines on the opposite side.

In the medieval northern wing on its eastern side there was a fraternity, i.e. a place of manual work of monks, used especially in winter. Fraternities were also often used as scriptorium, and the Kamieniec scriptorium was already confirmed at the end of the 13th century. The next room was occupied by a calefactory, a warming room in which the brothers could warm up in the winter time. The last two rooms in the western part of the north wing were occupied by the refectory and the kitchen. Perhaps, like in other buildings of this type, they were connected by openings for serving dishes, and in the dining room there could have been a pulpit for a reader reading the Bible during meals.

Current state

The monastery church dedicated to Saint James the Elder has survived to the present day in the best condition. It has preserved its Gothic shape, distorted only by the gables of the naves, chancel and transepts, transformed in the Baroque period, and the early modern porch by the west façade. From the monastery complex only some of the transformed in the early modern period buildings have survived: a part of the west wing and the north wing with the prelature. To the north of the church you can see also the foundations of the east wing and cloisters that once surrounded the inner patio. In the former abbots building, erected in the extension of the northern wing of the monastery, there is a branch of the State Archives of Wrocław. The abbey’s economic facilities are now occupied by the Breeding Center.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Kozaczewska-Golasz H., Halowe kościoły z XIII wieku na Śląsku, Wrocław 2015.

Kozaczewska-Golasz H., Halowe kościoły z XIV wieku na Śląsku, Wrocław 2013.

Łużyniecka E., Architektura klasztorów cysterskich, Wrocław 2002.

Pilch J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska, Warszawa 2005.