History

The early medieval stronghold in Zawodzie was built in the tribal era, around the second half of the 9th century, although continuous settlement in the area of later Kalisz existed from the Neolithic period, through the Bronze Age, the Early Iron Age, the pre-Roman period and the period of Roman influences. The stronghold was probably built on a cult site from the 7th/8th century, used by cremation cemeteries and a stone barrow. These facts and the similarity of the Kalisz name to the ancient “Kallisia”, recorded in 158 AD by Claudius Ptolemy, influenced the frequent recognition of Kalisz as the oldest settlement in Poland recorded in written sources. However, Kalisz appeared for the first time in a document that was undisputed as to its identification in 1106.

In the 10th century, the Kalisz stronghold in Zawodzie was incorporated into the Piast dynasty power, and the lands in its vicinity were subject to a colonization campaign, as a result of which it was surrounded by numerous smaller strongholds guarding access to it. The takeover of Kalisz was probably bloodless, because the castle ramparts were not damaged. The Piast rule revived the development of the stronghold and the neighboring craft settlement with the slightly later church of St. Adalbert and influenced the building of a market settlement nearby. Over time, the complex of Kalisz settlements became one of the most important politically and commercially centers in Poland. Moreover, it was one of the few that was probably not destroyed during the invasion of the Czech prince Bretislav in 1038, and in the following years it could have been a base for the recapture of lands by Kazimierz the Restorer.

According to the chronicle of Gallus Anonymus, in 1106 Prince Bolesław the Wrymouth captured and burned the Kalisz during the fights with his brother Zbigniew. Rebuilt in the following years, it was recorded as the seat of the diocese in the Life of Saint Otto of Bamberg, during his journey from Germany to Gniezno in 1124. Also in 1136, in the bull of Pope Innocent II, Kalisz was placed in the group of settlements belonging to the Archbishop of Gniezno. In the same document, the Kalisz castellany was mentioned for the first time, perhaps functioning since the times of king Bolesław the Brave. It was an administrative unit replacing the older strongholds districts and so called opole districts, one of about ninety that operated under Bolesław the Wrymouth. The castellany was headed by a comes, later called the castellan, who was the prince’s representative in the area of administering courts, commanding the army and collecting tributes.

During the period of the districts division, the Kalisz castellany became part of the senior district of Władysław II the Exile. In the following years it often changed from hand to hand. After the rebellion of the younger sons of Bolesław the Wrymouth, it probably passed to Mieszko III the Old in 1146, during whose rule Zawodzie achieved greatest development. The stronghold was expanded, and in the mid-12th century, a new stone collegiate church was founded, built on the site of an older wooden one. Presumably, it was supposed to be a kind of family necropolis, because not only Mieszko III, but also his son, also named Mieszko, was buried there. Kalisz was also the main center of ephemeral principalities several times, operating from 1186 to 1193 under the rule of Mieszko Mieszkowic, in 1193-1194 under Odon, son of Mieszko III, and from 1207 to 1217, when it was ruled by Odon’s son, Władysław.

Mieszko III the Old died in 1202 in Kalisz. This began an approximately thirty-year period of disputes and fights for the rights to the land of Kalisz between Władysław Odonic and Władysław Spindleshanks, who, after being expelled, handed the succession to the Silesian prince Henry the Bearded. In 1234, Henry the Bearded invaded Greater Poland and burned the stronghold in Zawodzie. It was decided to resettle the surviving population to a new place, but this decision may have been influenced not only by the scale of destruction, but also by climate change and the associated increasingly frequent floods. Ultimately, a new center was established about 1.5 km to the north, where the city of Kalisz eventually grew. The old stronghold and the collegiate church probably still functioned to some extent, but gradually fell into decline and at the end of the 13th century, Prince Przemysł handed the settlement over to the knight Jasiek. At the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, the role of the collegiate church of St. Paul was taken over by the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary located in the city, while the final end to the old settlement was brought by the raid of the Teutonic Knights in 1331.

Architecture

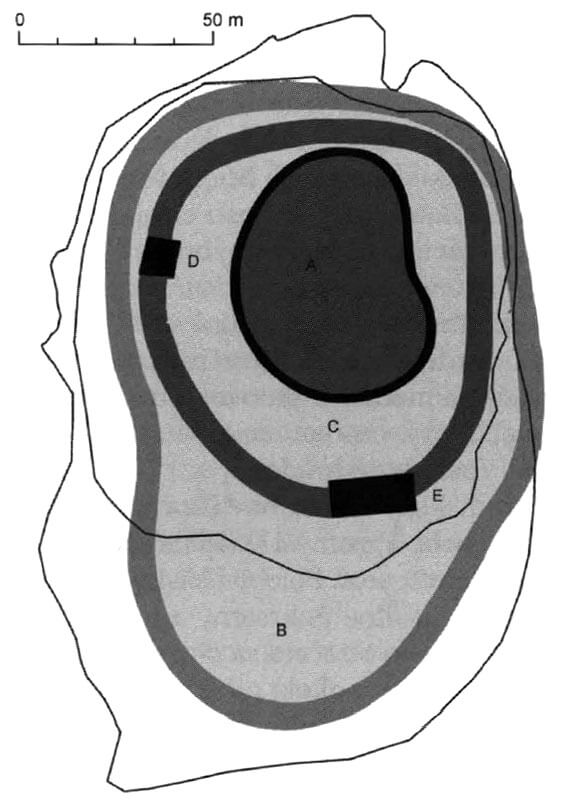

The stronghold was founded on the floodplains of the strongly meandering and branching Prosna River, opposite the confluence of the smaller Swędrynia River. Above, on the southern side, two more rivers flowed into the Prosna, the Piwonia flowing from the west and the Krępica from the east. Moreover, numerous streams flowed from the hills into the valley of the middle section of the Prosna River, which was widening near the stronghold, making the surrounding areas marshy and in some places swampy. The stronghold itself was located on a low terrace, raised several meters above the surrounding level. Originally, it had the form of a sandy island, covered with tufts of grass, made of material carried by the current of the neighboring river. This island, even before the ramparts were built, was strengthened with fascines and wood, as were the roads to it through marshy areas. The main current of the river initially passed around the island from the east, but after the fortifications expanding the range of dry land were built, it moved to the western side of the valley and stronghold.

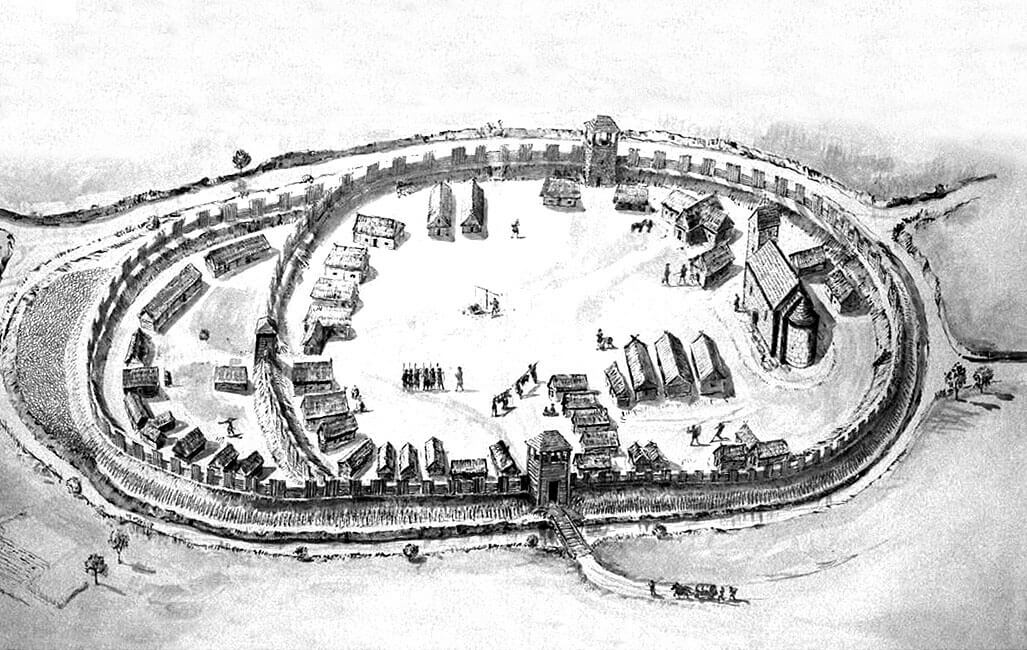

The tribal stronghold from the 9th century was a small structure with a shape similar to an oval, measuring approximately 75 x 50 meters. On the eastern side, the perimeter was slightly concave, perhaps due to the gate located there. In the 10th century, i.e. in the early Piast period, changes were made to the layout of the stronghold. The area of the ramparts was significantly enlarged, especially on the southern side, but also in the east and west, covering several natural elevations created by the river, as well as the area with a pagan barrow and a cemetery. In the northern part, the ramparts were placed on a high shore, and in the south, on a flat beach. From the east and west, the expansion of the yard had to be achieved at the expense of the river bed. The whole stronghold then measured approximately 80 x 100 meters. Then, at the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries, the area of the yard was increased again, this time to approximately 100 x 175 meters. Already in the 10th century, the interior was divided into the north-eastern sacral part and a larger residential and administrative part on the southern side, with both parts separated by a depression related to the original course of the river bed. In the southern part of the stronghold, there was a wooden building measuring 3.9 x 4.2 meters, perhaps the seat of the local ruler or a kind of large warehouse. There were probably more buildings next to it. Numerous non-fortified settlements in Zawodzie and the Old Town area also had residential and economic functions.

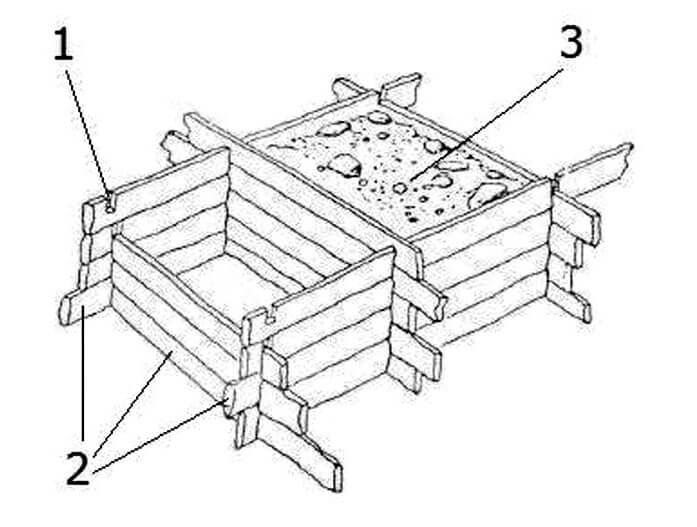

The oldest fortifications of the stronghold from the second half of the 9th century had the form of a wood and earth rampart, approximately 10 meters wide at the base, made of log boxes filled with large stones and earth. Probably the rows of these boxes stabilized on both sides the core of the rampart with a sandwich structure. The rampart had to be crowned with a breastwork (e.g. in the form of a palisade), protecting the guards and defenders. Additionally, on the side of the inner yard the rampart structure was stabilized by poles driven at an angle. From the outside, there were two rows of poles, partially hewn or barked, also driven diagonally into the ground, with the pointed part facing the foreground. It were placed approximately 1-1.5 meters from the rampart and the space between the log boxes and the outer fortifications was filled with fascine to strengthen the ground.

The first Piast ramparts from the 10th century were built using the sandwich technique, with the older embankments being partially dismantled and the building material from them used to level depressions in the area. Even part of the structure of the pagan barrow was used to build new ramparts. The structure of the rampart then consisted of horizontally placed beams running along the face of the embankment, placed on transverse logs covered with earth. The rampart of this phase was 6 to 10 meters wide at the base. Like the older fortifications, the 10th-century rampart in the crown was probably topped with a wall-walk and some kind of breastwork, for example in the form of a palisade. When the stronghold was enlarged at the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries, the rampart reached 9.5 meters wide at the base and up to 6 meters high. Its core consisted of wooden boxes made of oak logs, tied using the hook technique and reinforced with stone facing. Most of the perimeter was built on sandbanks, but in the north they were built on the older part of the ramparts, and in the east the second phase fortifications were partially used. From the outside, the ramparts were preceded by a stockade, placed at the foot of the embankment.

At the end of the 12th century, due to frequent floods and the rising water level at the bottom of the Prosna valley, the area of the stronghold was reduced to approximately 80 x 100 meters and the fortifications were strengthened. The southern part of the site was abandoned, leaving only a short section of the old rampart, which, after being reinforced with a stone cladding, served as a spur isolated from the main part of the stronghold, protecting against the destructive effects of Prosna. The inner rampart separating the church from the residential part of the stronghold has probably also disappeared. In the southern part of the shortened courtyard, on a high ground near the rampart, there may have been a princely residence. Additionally, a four-sided defensive tower was built within the fortifications on the western side. It was placed on a rampart, but its foundations were made of erratic stones, while the above-ground part could have been of brick construction. In plan, the tower had irregular dimensions of 9.6 x 11 x 9.3 x 9 meters.

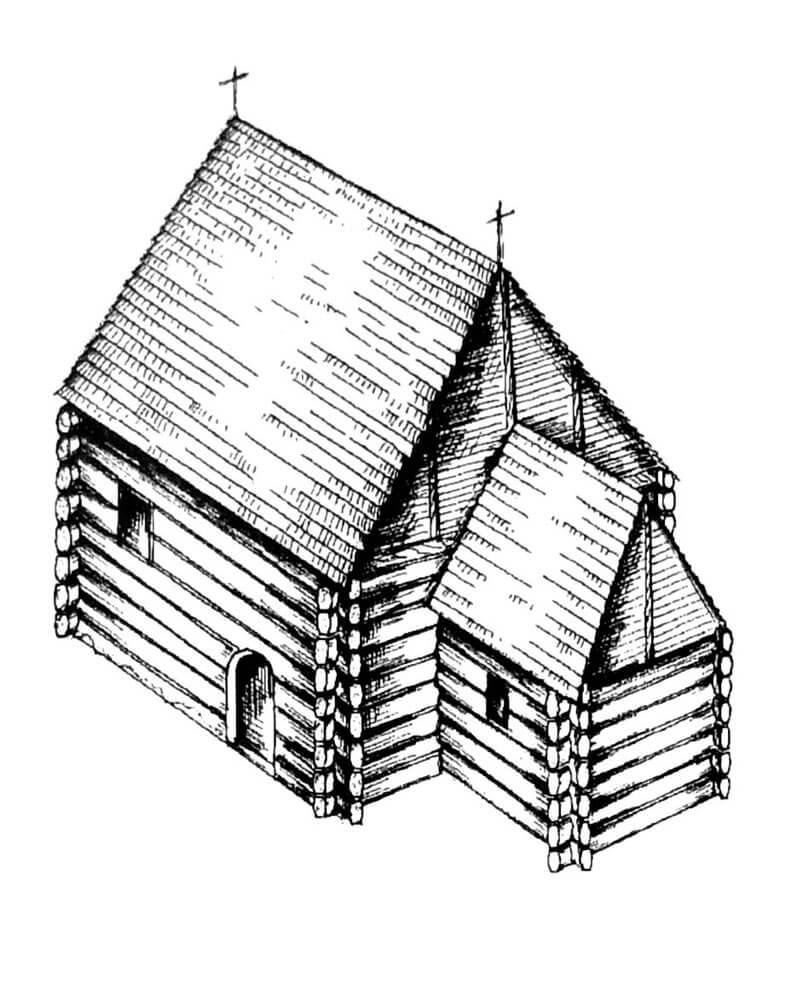

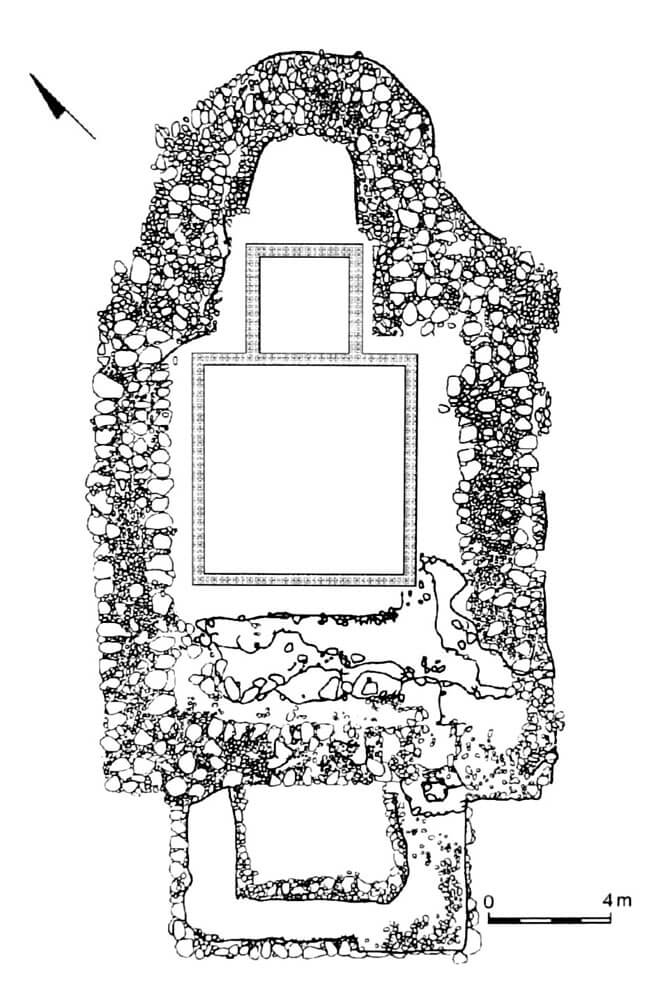

The northern part of the stronghold was occupied by sacral buildings and houses associated with them. The earliest was a wooden church from the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries, around which the dead were buried. The cemetery, together with the church and the building adjacent to it from the west were surrounded by a rampart from the north and east, as well as a separate internal rampart from the south and west. The church consisted of a nave measuring 7.6 x 7.8 meters and a four-sided chancel measuring 3.9 x 3.8 meters, which was shifted to the north due to the configuration of the terrain. It was built in a log structure, probably with boarded walls. Inside, the walls were plastered with clay, among which pieces of molten bronze were found, perhaps melted nails used to attach decorative fabrics. The floor of the church was also wooden, with the usable level of the chancel higher than the nave by about 20-30 cm.

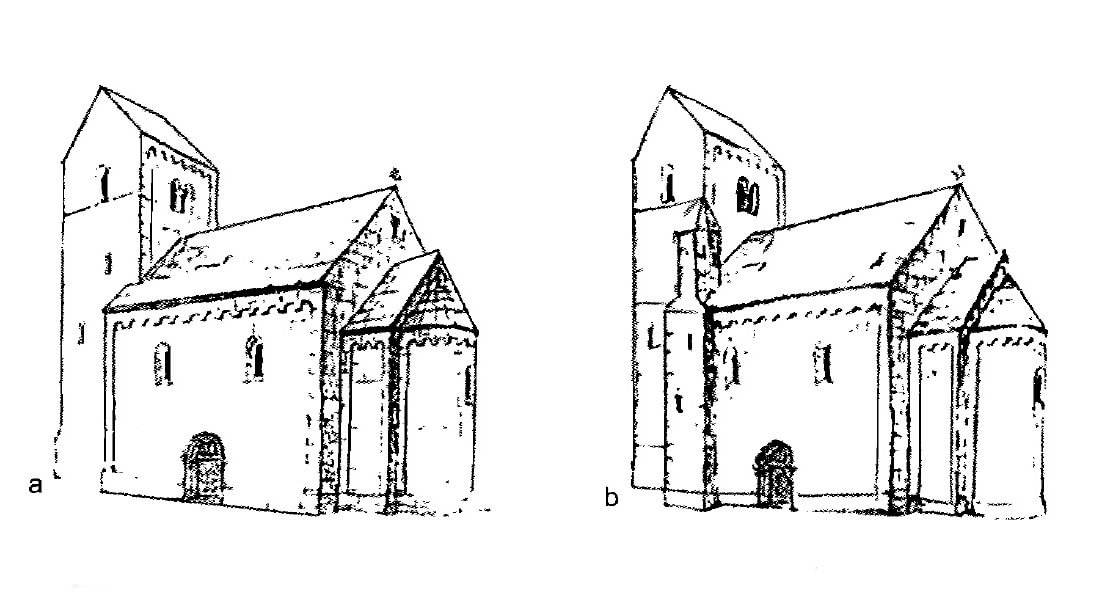

In the mid-12th century, the Romanesque church of St. Paul was built in place of the timber temple, made of ashlars with carefully crafted faces, similar in shape to squares or rectangles, set on foundations of massive, irregular boulders. Due to the unstable ground under some of the walls, a grid of wooden logs and dense piling were used to harden the earth across the entire width of the foundation. In the first phase, the church was an aisleless building with nave dimensions of 17 x 15 meters, closed on the east by a shallow bay of the chancel with an apse, and on the west equipped with a four-sided tower measuring 5.3 x 10 meters. The latter had a characteristic form with longer sides located north-south. It had no entrance from the outside on the ground floor, it only had to be connected to the nave via an arcade or portal. The first floor of the tower could open to the nave with a two-light or three-light opening, or there was an altar recess on the axis of the eastern wall. The main entrance to the church was through the southern wall of the nave.

In the second phase of construction, the interior of the church was enriched with a western gallery, located in the nave and opened to it. The entrance to the gallery was through a stair turret added on the south-west side, probably also connected to the main tower. There was also a second, direct entrance from the nave to the gallery, via stairs added to the southern wall. Two separate entrances to the gallery were a common custom at that time, although their significance is unknown. The stair turret probably also connected the upper floors of the tower with the gallery. The ground floor of the gallery probably opened onto the nave with two arcades based on a central column. From the first floor, the nave may have been viewed through a three-light opening. The backroom of the gallery was on the first floor of the tower.

The architectural detail of the church was relatively rich and varied. The internal facades of the apse, and perhaps the entire chancel, were divided by semi-columns, located on a low plinth surrounding the entire altar part of the church. It probably supported blind arcades, topped with an impost band running at the base of the barrel vault of the chancel and the conch of the apse. Moreover, the splayed windows of the church were framed with columns, and the openings themselves were glazed with stained glass. The most decorative form must had the southern entrance portal, of an unfortunately unknown shape, perhaps embedded in a shallow avant-corps. Inside the chancel, the main altar was probably covered with a ciborium, i.e. a canopy supported by four columns. It is almost certain that it was separated from the nave by a rood screen, placed on a light foundation running in the line of the chancel arcade or at the edge of the nave. From the outside, the church facades were most likely decorated with pilaster strips and arcade friezes.

Church of St. Paul had a clear gradation of height in three distinctive sections, starting from the highest western part (main tower) and ending with the lowest eastern part (apse). In the church in Kalisz, the local Greater Poland tradition of equipping important princely temples with axially placed towers was most likely combined with the model of a three-part aisleless church, which had been spreading since the mid-12th century. This type was formed and spread in the Romanesque provincial architecture of Germany and northern Italy, strongly influencing the countries of Central Europe. The plan of the tower in the form of a rectangle placed transversely to the axis of the church, could be a reduced form of the monumental western massifs of Ottonian provenance. Preceding the apse with a chancel bay was probably due to the collegiate rank of the church, which had to be larger in its liturgical part than ordinary temple. There must have been side altars, perhaps an additional altar was also located in the gallery.

Current state

Currently, in the medieval stronghold of Zawodzie in Kalisz, there is the Archaeological Reserve “Kaliski Gród Piastów”, which is a branch of the District Museum of the Kalisz Land. Within it, a gate with a section of wooden fortifications in the form of a palisade and a stockade was recreated. The tower and the bridge over the moat were reconstructed within the original defensive embankment. The foundations of the Romanesque church were rebuilt, inside which the outline of an earlier wooden church was marked. In addition, seven residential houses were built, differing in size, walls construction, roof covering, and purpose. Attempts were made to recreate the huts inhabited by a saddler, a merchant, weavers, servants, a knight, a blacksmith and a potter. The reconstruction of the barrow tomb was also included, and even dugout canoes were built. In the open-air museum you can take part in numerous outdoor events.

bibliography:

Baranowski T., Najwcześniejsze budownictwo sakralne Kalisza [w:] Początki architektury monumentalnej w Polsce, red. Janiak T., Stryniak D., Gniezno 2004.

Gród Kalisz-Zawodzie we wczesnym średniowieczu, red. T.Baranowski, D.Cyngot, Warszawa 2023.

Rodzińska – Chorąży T., Kościół pod wezwaniem św. Pawła na Zawodziu w Kaliszu w kontekście architektury w Polsce na przełomie XII i XIII wieku [w:] Kalisz na przestrzeni wieków: konferencja naukowa pod przewodnictwem prof. dr hab. Henryka Samsonowicza, red. Baranowski T., Buko A., Kalisz 2013.

Rodzińska – Chorąży T., Kościół pod wezwaniem św. Pawła na Zawodziu w Kaliszu – na tle architektury romańskiej [w:] Modus. Prace z historii sztuki IV, 2003.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 1, architektura sakralna, Kalisz 2007.