History

In 1222, prince Henry the Bearded gave Nicholas, the Wrocław cathedral canon and notary of the prince’s office, permission to settle Cistercian brothers in Henryków. The condition was that the official founder and patron of the abbey would be the son and successor of Henry the Bearded, Henry I, thanks to which monasery had a chance for rapid development under the protection of the Silesian branch of the Piast dynasty. Nicholas donated for the monastery the land received from the prince over the upper Oława river, to which the first monks arrived in 1227. They were nine monks from Lubiąż Abbey, headed by Abbot Peter. A year later, a document was issued approving all the properties of the monastery and in 1228 two altars of the first timber monastery church were consecrated.

The abbey developed quite dynamically until the Mongol invasion in 1241, when the church and monastery were burned and looted. In addition, the situation of the monastery was aggravated by the death at Legnica Battle of the son of Henry the Bearded, Prince Henry the Pious, then patron of the Henryków abbey. After the Mongol invasion, the Cistercians began to rebuild the monastery and recover the property. In order to organize the property, a document called the Henryków Book began to be written (from around the mid-thirteenth century to the end of the fourteenth century), which, in addition to describing the history of the foundation, mentioned the possessions of the monastery in Henryków. It has become one of the most valuable monuments of Polish literature, as it contains, among others, the first sentence written in Polish (“day, ut ia pobrusa a ti poziwai”).

In the second half of the thirteenth century Cistercians strengthened their position and increased wealth, although after the death of Henry the Pious, subsequent rulers of the Silesia were less interested in the fate of the abbey. The income came primarily from the land estates making granges and from craft activities, rents, mines and customs. The Henryków monks also dealt with brewing, milling, shoemaking and weaving. The establishment of sister abbey in Krzeszów is evidence of their growing position in 1292. According to written sources, at the end of the 13th century Henryków housed as many as 80 monks and lay brothers who employed numerous workers and slaves.

After 1241, further work began on the construction of the abbey church, which lasted until the mid-fourteenth century. It is known that in 1339 there were already built monastery buildings with a refectory and chapter house, there was also a kitchen (mentioned in 1270), a brewery and a bakery (mentioned in 1334). In 1291, the knight Konrad founded the chapel of St. Andrew, intended for the population of the village, and at least from 1281 there was a monastery school and a hospice since 1318. Sources also often mention mills, a weaving workshop and a late-medieval inn. In the abbey church, the princes of Ziębice arranged a family tomb. In 1341, Prince Bolko II of Ziębice was buried in the abbey, and soon after his wife.

The prosperity of the monastery was brought to an end by the Hussite wars that hit the abbey in the years 1428–1430. The monastery was burned and plundered, and the monks fled to Nysa and Wrocław. After the reconstruction, the monastery was again destroyed in 1438 by the army of Zygmunt von Rachenau, and in 1459 the invasion of the Czech army of King George of Podebrady. After a short period of peace, due to the spreading Reformation, the process of fall of the community began, which in 1553 had only two or three monks. The total decline did not occur because brothers of German origin from the monasteries of Greater Poland in Łekno, Ląd and Obry came to Henryków.

The re-development of the monastery took place since the mid-16th century. At the time, abbot Andrew had great merits, during which reign, Renaissance elements of monastery buildings were created. Reforms of discipline and order’s work were also carried out, which contributed to improving the condition of the abbey. The monks were ordered to close the dormitory for the night, the trysts of food and drink were forbidden, just like pointless disputes after the evening set. Women were also forbidden to enter the monastery. In parallel with the spiritual renewal, economic reconstruction took place. The monastery obtained permission to run outside an inn and the right to brew beer. The development process of the abbey was interrupted by the Thirty Years’ War, when it was plundered and burnt. Also a significant part of the original monastery library was destroyed. The disaster was increased by the plague that broke out in the abbey in 1633.

After the Thirty Years’ War the abbots Melchior Welzel, Henry Kahlert and Tobias Ackermann restored the monastery to its former glory. During this period, most of the Baroque buildings were created, and the monastery church was rebuilt in this style. At that time, it became an important Marian sanctuary and a place of worship of Saint Joseph. The economic strength of the abbey in that period was confirmed by the acquisition in 1699 of the Cistercian abbey in Zirc in Hungary, destroyed by the Turks. From that time, up to the secularization of the monastery, the Henryków abbot, as part of a personal union, was the abbot of two monasteries. Around 1760 a chapel of St. Mary Magdalene was built, which became the mausoleum of the Piasts of Ziębice. Henryków’s development stopped in the period of Silesian wars between Prussia and Austria in 1741-1762. In the monastery, the army was stationed several times, plundering the monastic treasury, and high war contributions were imposed on the monks. The end of the monastery’s functioning brought the Napoleonic wars. In 1801, the Prussian authorities closed the monastery gymnasium and commandeered a monastery library with the richest book collection in Silesia, numbering 132 manuscripts and 20,000 books. In 1810, the Prussian king Frederick William III, seeking revenue for the strengthening of the army, announced the secularization edict. As a result, the monks were forced to leave the abbey, taking only the habit, breviary and food for two days, and the Henryków Abbey was liquidated.

Shortly after the secularization, Henryków‘s estate was bought by the Dutch queen Friederike Wilhelmine, the sister of the king of Prussia. The monastery was slightly rebuilt in order to use it as a magnate residence. In 1863 it was taken over by inheritance by the Saxe-Weimar princes. In 1879, a landscape park was created near the monastery, as well as an Italian-style garden. Later in the abbey’s buildings there was an elite hospital for the mentally ill. During the Third Reich, a military factory was organized in Henryków, in which prisoners from Luxembourg worked. At the end of the war, the monastery was robbed and devastated.

Architecture

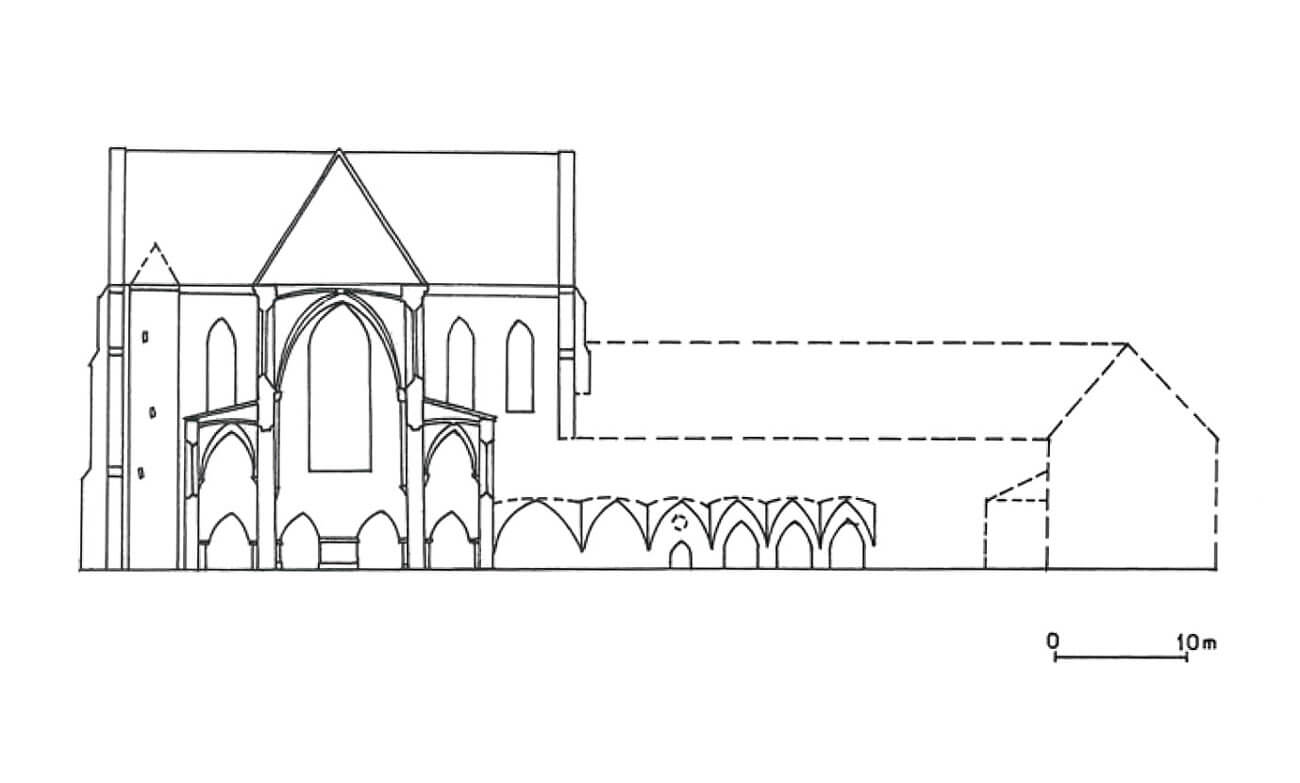

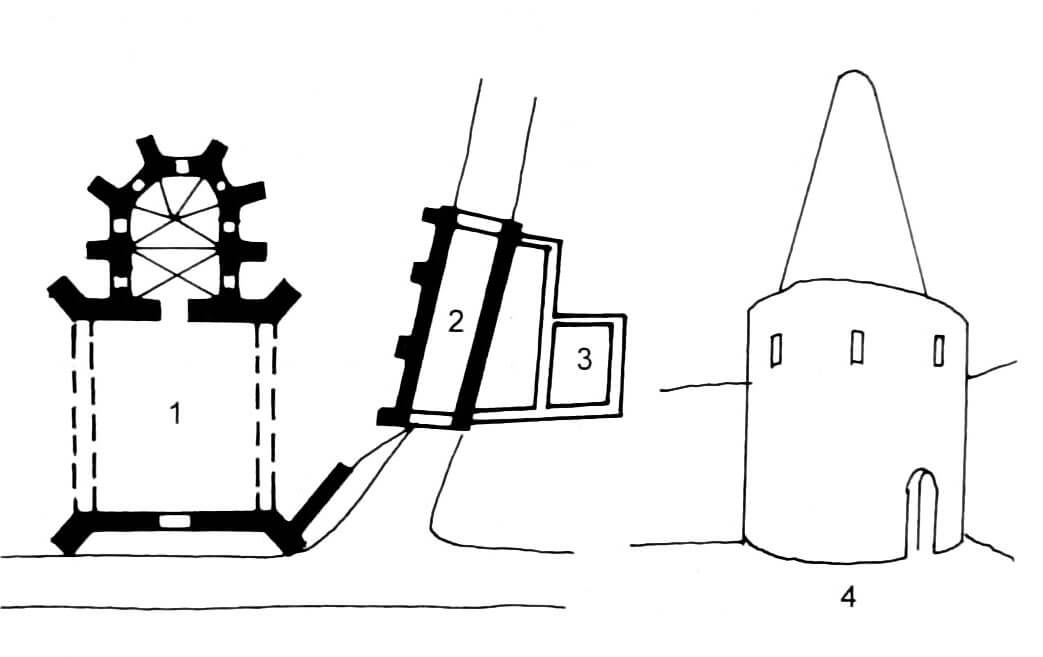

The Henryków Abbey was founded on the bank of the Oława River, whose bed separated the monastery from the village. At the beginning of the fourteenth century, a small church of St. Andrew, one-nave with a polygonal chancel, intended for the local population, was erected. Probably next to it ran the main road to the monastery, reaching the courtyard where the brick granary stood (the so-called Servants House). The originally not divided main courtyard from the south-east was enclosed by the abbey church and enclosure buildings. Opposite this complex was a monastery manor with arable land reaching the banks of the river. Probably the buildings of the brewery, bakery, mill and weaving workshop, well-known from medieval records, were built there. The whole abbey was surrounded by a stone wall, reinforced in the corner by the cylindrical, small tower of the half defensive and half symbolic function.

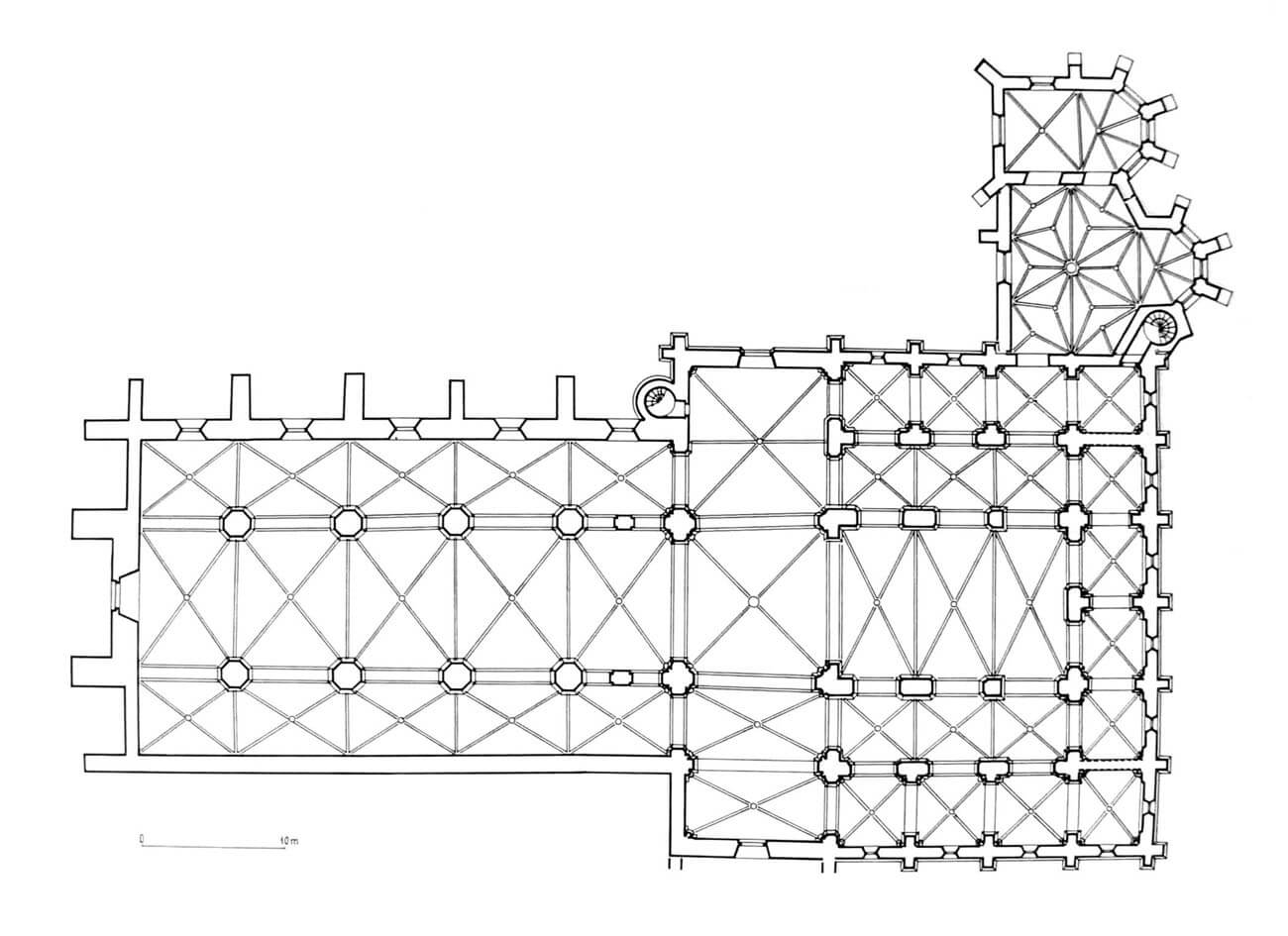

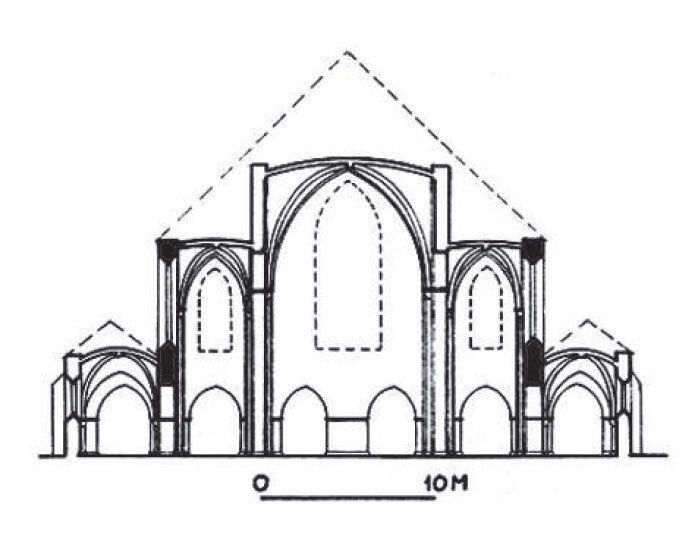

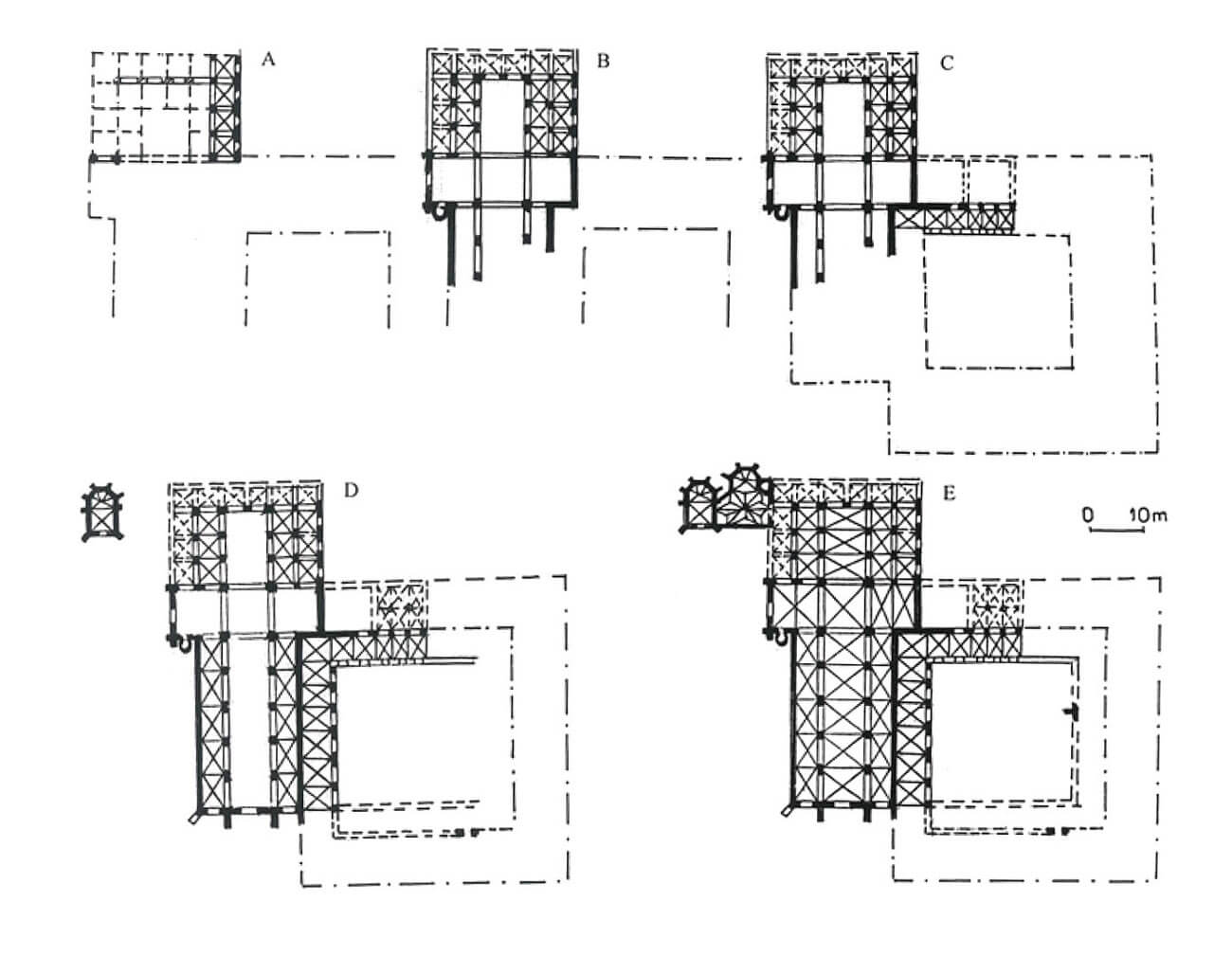

The medieval monastery church in Henryków was planned as a building in the form of a basilica, a three-aisle with a transept and a chancel with an ambulatory, in a hall layout, surrounded by a wreath of low chapels. For the Tatar invasion in 1241 only a chancel was completed, and after the break in construction, the form of the hall presbytery was abandoned in favor of the basilica type, in which the central nave was higher than originally planned. Built-up ancillary columns with heads were not used to embed the vault’s ribs, but were raised and the ribs were supported on new heads. Three aisles were probably covered by one gable roof. The chapels were much lower and perhaps also covered with gable roofs, which allowed for a significant reduction of the windows high in the chancel walls. The choir was closed from the east with a straight wall, surrounded by an ambulaltory and two lines of chapels in the north and south side.

By mid-fourteenth century, a transept with an internal width of 30 meters and five bay nave were completed. Probably after the erection of the transept, the building material was missing, so that the first bay of the nave was built of defective and undersized bricks, which led to a disorder of the brick arrangement and then cracks in the northern wall of the nave and its collapse on the pillar line. The shortage of bricks forced builders to finish the nave with greater use of local unworked stone. Around 1506, two chapels were added to the chancel from the north-east: the Holy Cross and the Holy Sepulcher (on the site of an older one from the 14th century with the same name), and in 1608 a tower was erected from the west, which still had a Gothic form.

Outside, the church, which eventually reached 66.6 meters in length, was strengthened with buttresses. In the presbytery, transept and central nave, there were ogival windows decorated with tracery. A pointed portal of a modest form led from the west inside the church. The 19.7 meters wide nave and the chancel were covered with rib vaults, supported on six-sided pillars in the naves and rectangular in the chancel. The chapel of the Holy Cross was founded on a cruciform plan with pentagonal arms and covered with a rib vault. The Chapel of the Holy Sepulcher with the nave on a polygon plan and a small presbytery ended in a pentagon form, is covered with a stellar vault supported by a single pillar.

The monastery church was built in the Cistercian spatial arrangement with a Gothic vault structure and Gothic tracery forms. In contrast, romanesque elements appeared in the decoration of some capitals, corbels supporting the ancillary columns and bases with a corner leaf. These manifestations of the romanesque forms were limited to the transept and chancel erected earlier. The nave was built only in Gothic style.

The church inside was originally covered with architectural polychrome, which strengthened the natural red of the bricks and emphasized the joints with a white strip 15-20 millimeters wide. The outer facades were also multicolored. The red of the bricks was strengthened, the joints were emphasized with white stripes, the under-eaves cornice was painted in red – gray – blue stripes, and the splayed windows were covered with alternating red and gray-blue paint, creating a checkerboard pattern.

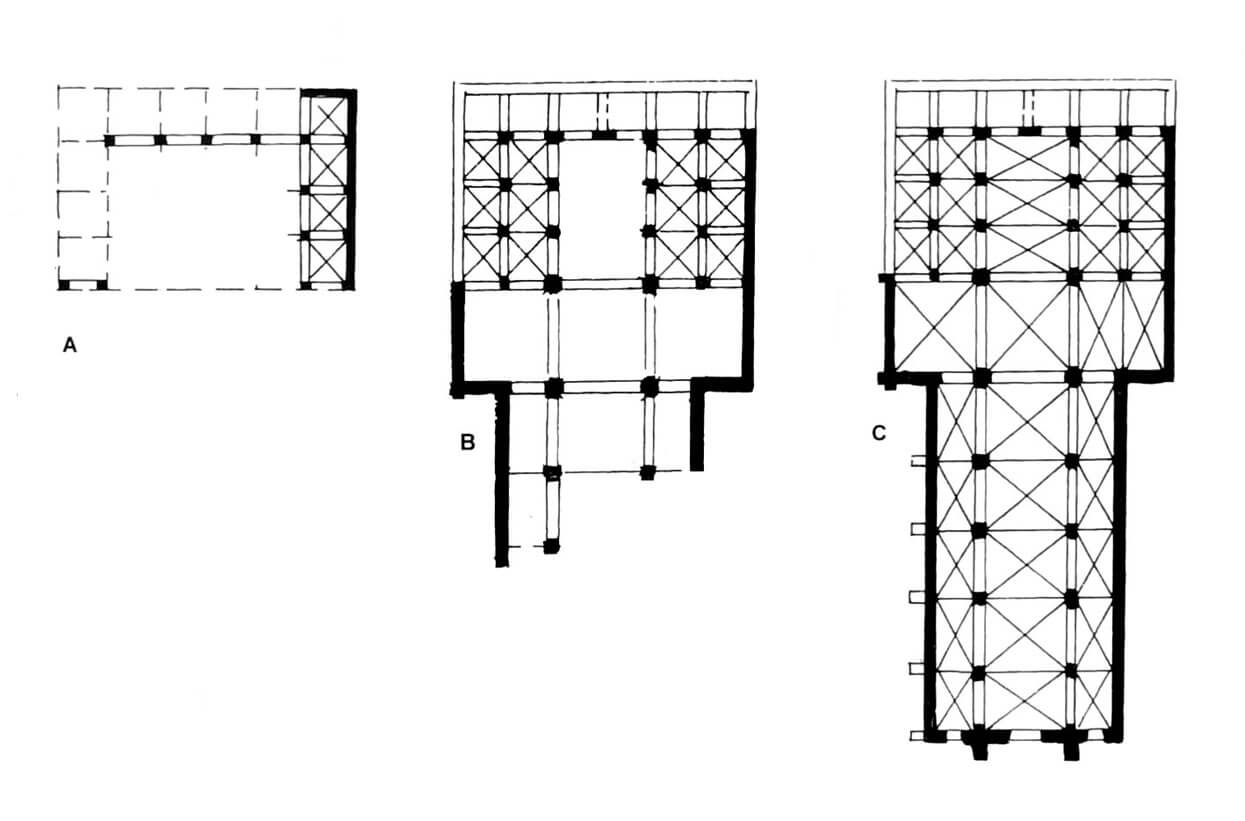

The abbey buildings were located south of the church. They consisted of three wings enclosing the inner patio. The eastern wing was two-story, and the western and southern one-story. The cloisters were characterized by a various width of bays, from 3.7 meters to 6 meters, which would indicate that they were not completely planned at once, but were added gradually. The consequence of the different widths of the bays was also the different height of the vaults of the cloisters. In addition, the cloister differed in building material. Parts made in the second half of the 13th century were brick, while those from the first half of the 14th century were stone (and additionally made less solidly).

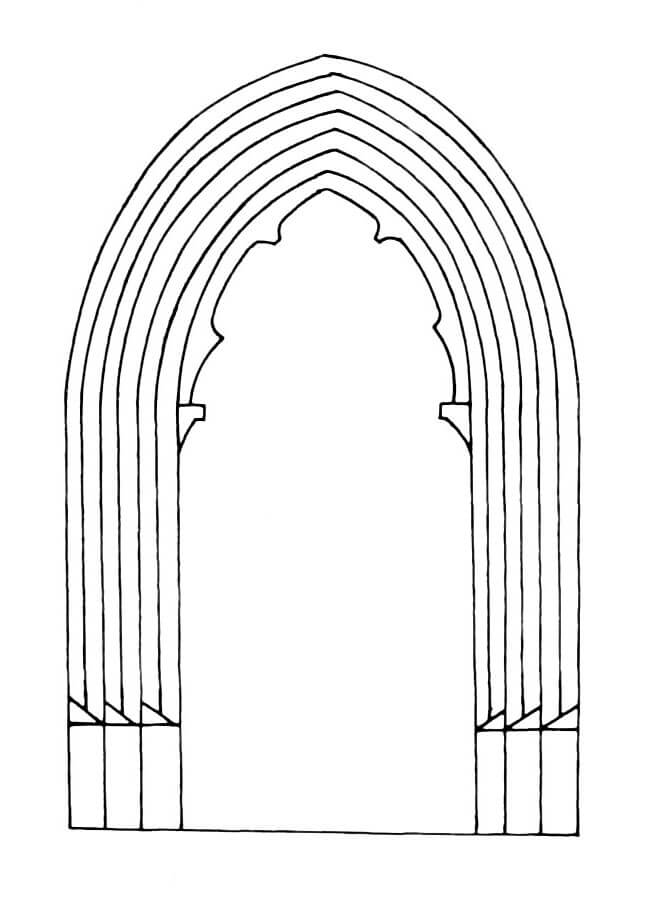

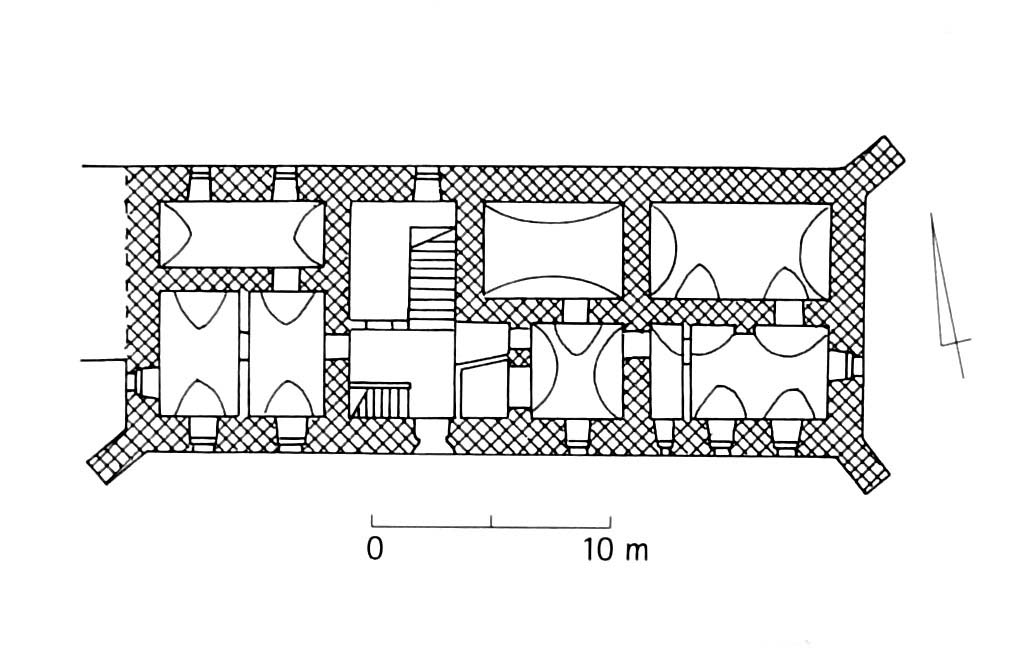

By comparison with other typical Cistercian abbeys, it can be assumed that the eastern wing housed the sacristy, chapter house and fraternity on the ground floor, and on the first floor a dormitory of monks connected with the church on one side and latrines on the other. Of these, the chapter house was the most important and ornate. It was the hall in which the brothers together with the abbot, gathered every day to jointly deal with the affairs of the monastery and conduct courts over monks who did not follow the rule of order. To the chapter house led from the cloister an imposing, polychrome portal, on the sides of which there were openings of a similar form, perhaps alike to those created around 1320 in the Maulbronn Abbey. Thanks to them, lay brothers and novices standing in the cloister could listen to the deliberations. Under the walls of the chapter hall, there were benches, the abbey’s throne opposite the entrance, and a reading desk in the center. The Henryków chapter house was three-bay and two-aisle.

South wings were most often allocated for the refectory adjacent to the kitchen and to the calefactory, that is the only room heated throughout the winter. The west wings usually housed the monastery’s pantries and warehouses (cellarium), rooms for lay brothers: their refectory and fraternity on the lower floor and dormitory on the first floor. The fraternities or day rooms were chambers in which monks or lay brothers worked, often it was scriptorium or room used for other manual works, especially in winter. In addition, the enclosure complex had to have an entrance lobby connected to the cloisters, enabling access to the abbey from the monastery economic buildings or from the church cemetery side. The necessary rooms were also parlours, the only chambers in the abbey where the monks could talk without fear of breaking their vows of silence. They were often located in the western wings, where lay people were contacted about the monastery cellar. In addition, it is known that in Henryków during the late Middle Ages, the abbot had his residence in a separate building.

Current state

At present, only the monastery church and the chapels of the Holy Sepulcher and the Holy Cross on its northern side have preserved the medieval stylistic features. Unfortunately, the western façade of the church was completely rebuilt in the Baroque period, as was the whole monastery buildings. Works from the end of the 17th century blurred the details of the stonework in the chancel and aisles, but are preserved under stucco. Through the walling, corner ancillary columns in the presbytery turn into square in cross-section pillars, and the ancillary columns of the central nave and inter-nave arcades were completely bricked up or transformed. Among the side chapels in the original condition one has survived in the southern aisle and one in northern aisle, while the others lost their vaults.

Since 1949, the abbey is again owned by Cistercians, who make it available for visitors, daily from May to September. Out of season only after prior telephone contact.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Kozaczewska-Golasz H., Halowe kościoły z XIII wieku na Śląsku, Wrocław 2015.

Łużyniecka E., Architektura klasztorów cysterskich, Wrocław 2002.

Łużyniecka E., Święcka E., Badania architektury opactwa cysterskiego w Henrykowie prowadzone w latach 2003 i 2006, “Architectus”, 2(20), 2006.

Pilch J., Leksykon zabytków architektury Dolnego Śląska, Warszawa 2005.

Świechowski Z., Architektura na Śląsku do połowy XIII wieku, Warszawa 1955.