History

On the site of the Grudziądz castle, there was originally a Slavic timber – earth defensive hillfort, recorded for the first time in a document by Bolesław the Bold under the name “Castrum Grudomzch”. It was used in the times of the early Piast monarchy to control the crossing of the Vistula River, and then it was part of the castellany, playing an important role on the northern borders of the state. It could have been destroyed during the raids of Prussian tribes, because in the document of the Duke of Mazovia, Konrad, from 1222, it was described as the “quondam castrum”. In that year, the prince gave the hillfort along with a number of other strongholds to the Prussian bishop Christian, wanting to support his mission among the pagans. The stronghold could remain in the hands of the bishop until his death in 1245, although it cannot be ruled out that already around 1231 it was taken over by the Teutonic Knights, who then made efforts to eliminate the competitive authority.

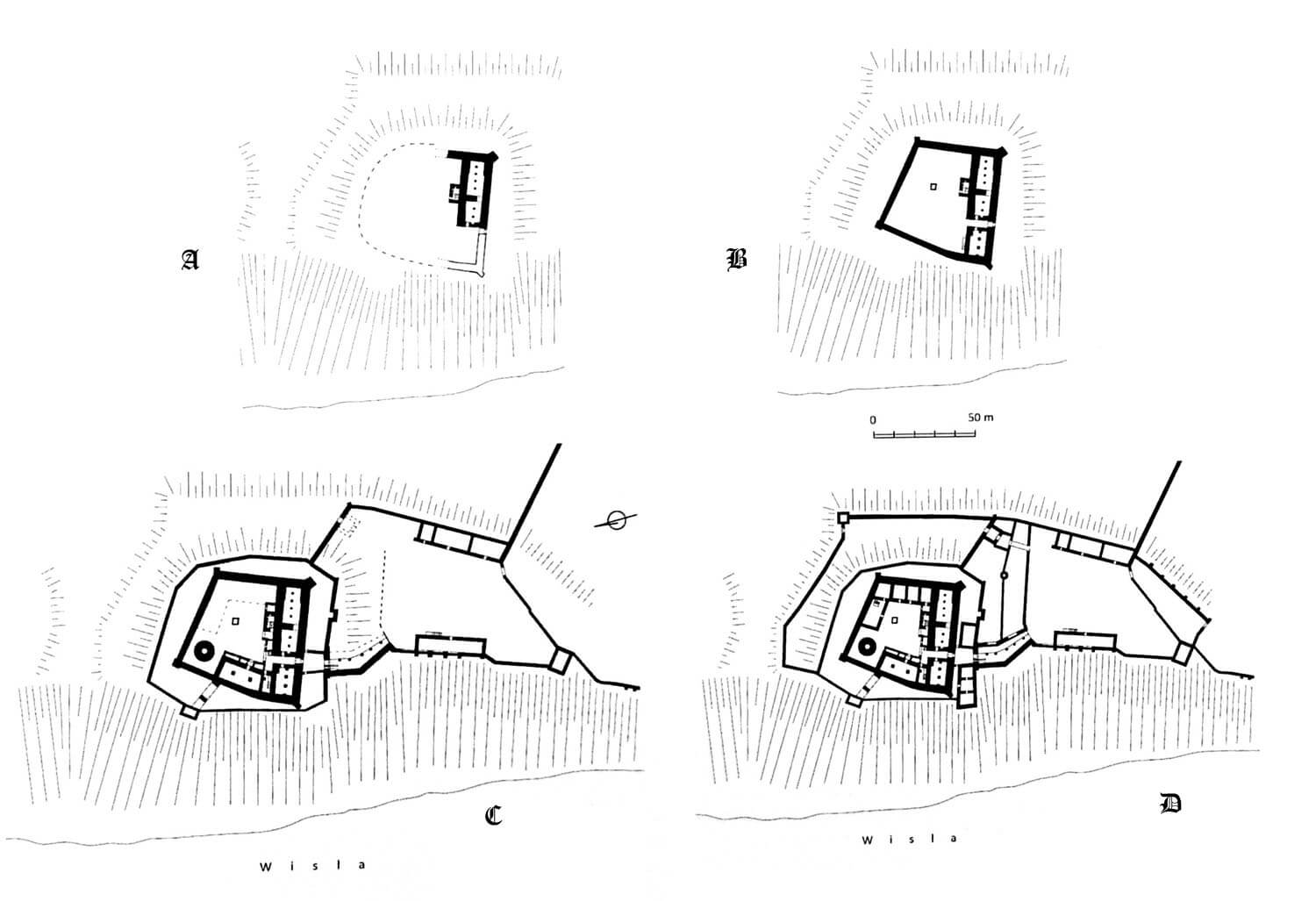

The construction of the brick Teutonic seat of the Teutonic Knights called Graudenz took place in the second half of the 13th century. The first phase of construction probably began after the pacification of the second Prussian Uprising, i.e. at the end of the 1270s. The works could also begin before the Prussian Uprising, as the beginnings of the Grudziądz commandry date back to the period between 1263 and 1269, but in such a case they had to be interrupted while the rebellion was suppressed. Moreover, losses may have been incurred during war, because in 1277 the area around Grudziądz was plundered by the Yotvingians led by Skomand. In 1288, Grudziądz was visited by the Land Master, Meinhard von Querfurt, in connection with the construction of the Vistula embankments. In 1290, the castle chapel was consecrated, which, however, was not tantamount to the completion of construction works. Shortly after 1300, the main bergfried tower, called Klimek, was erected, in the first quarter of the 14th century the west wing of the castle was also built.

In 1388, part of the west wing, together with the dansker and the commander’s house, fell to the Vistula due to heavy rains, but it was rebuilt in a similar form. According to the inventories of the Teutonic Knights, in the years 1404-1440 there was also a kitchen, bakery and brewery in the castle, the fortifications of the outer bailey in the south and external fortifications had to be completed, the latter in the second half of the fourteenth century expanded on the eastern and northern sides. However, already in the years 1442 – 1446, during the rule of the Grand Master Konrad von Erlichshausen, some of the buildings were in a bad condition, among others, the convent house needed repair. Intensive construction and repair works were also carried out in the outer bailey.

The castle in Grudziądz must have been considered particularly defensive, since during the war with Poland, Grand Master Werner von Orseln chose it as his headquarter in 1330. Despite this, after the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, Grudziądz was temporarily occupied by Polish troops, after King Władysław Jagiełło summoned in a letter the inhabitants of Toruń and other Chełmno towns to capture the castle. The king handed it over to the Poznań castellan, Mościcki from Stążew, but at the end of the year Grudziądz was recaptured by the Teutonic Knights. The Teutonic garrison was to fight against the Polish garrison of Radzyń, although this did not affect the course of the war, which ended in 1411 with the First Peace of Toruń, under which Grudziądz remained the property of the Teutonic Knights.

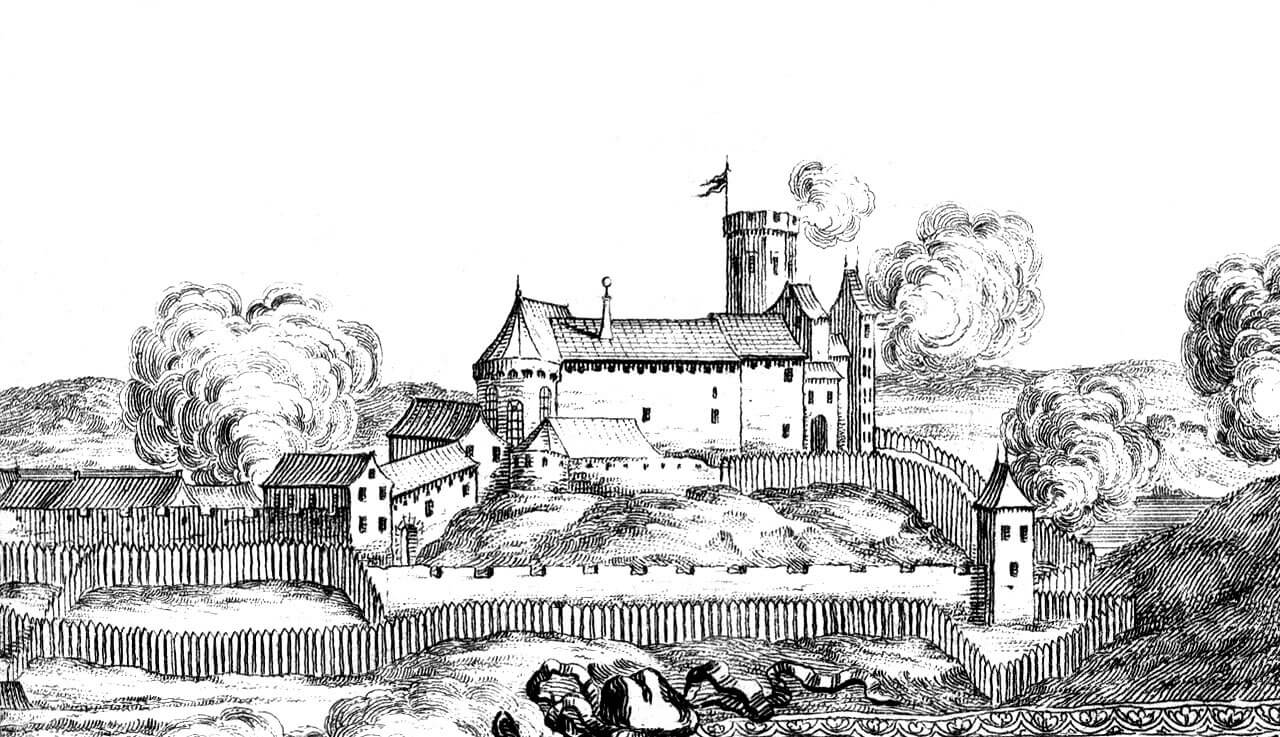

Inspections carried out before the mid-15th century emphasized the poor condition of the Grudziądz castle, which could have contributed to its quick capture during the Thirteen Years’ War. In 1454, the forces of the Prussian Confederation captured the castle after a week-long siege, in the absence of the then commander. The Teutonic Knights’ two attempts to recapture it the following year proved unsuccessful. After the end of the war in 1466 and the incorporation of Royal Prussia into Poland, the castle became the seat of the starosts of Grudziądz. The new administrators removed the damages caused by military operations, and then in the second half of the 16th century, they rebuilt the castle interiors in line with early modern needs.

In 1655, Grudziądz was occupied by the Swedes, who modernized the fortifications. Four years later, the Poles recaptured the stronghold, but the walls and roofs of the buildings were partially destroyed. Despite repairs carried out around 1765 by the starost Augustyn Stanisław von der Goltz, the process of destruction continued in the 18th century (in 1795 the roof over the castle chapel collapsed). Eventually in the years 1801-1804 the castle was almost completely demolished on the order of the Prussian king Frederick William II, in order to use bricks to build an early modern fortress and prison. After the intervention of Queen Louise in 1806, only the demolition of the main tower was stopped, but unfortunately it was blown up by German soldiers in 1945.

Architecture

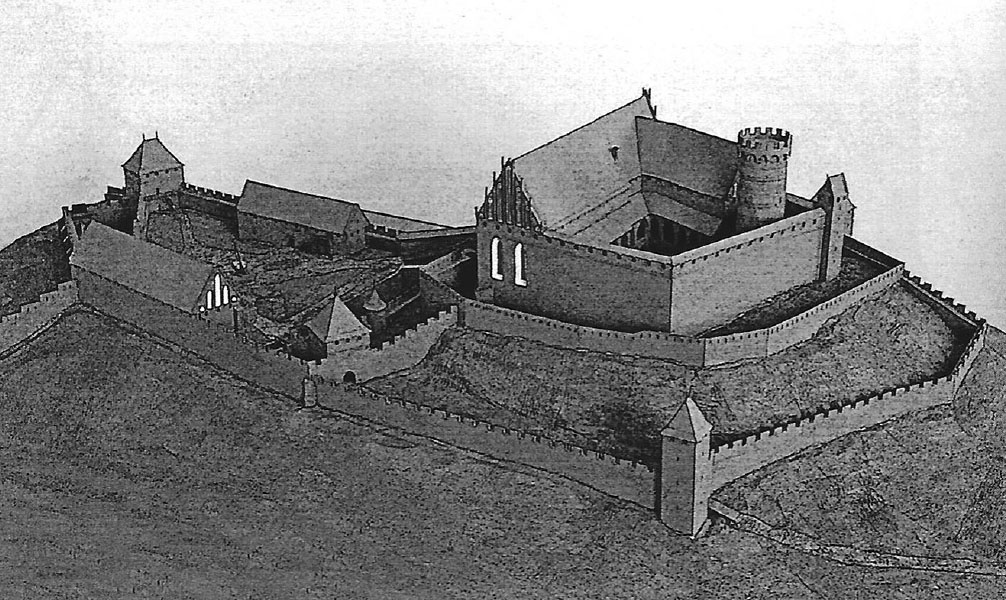

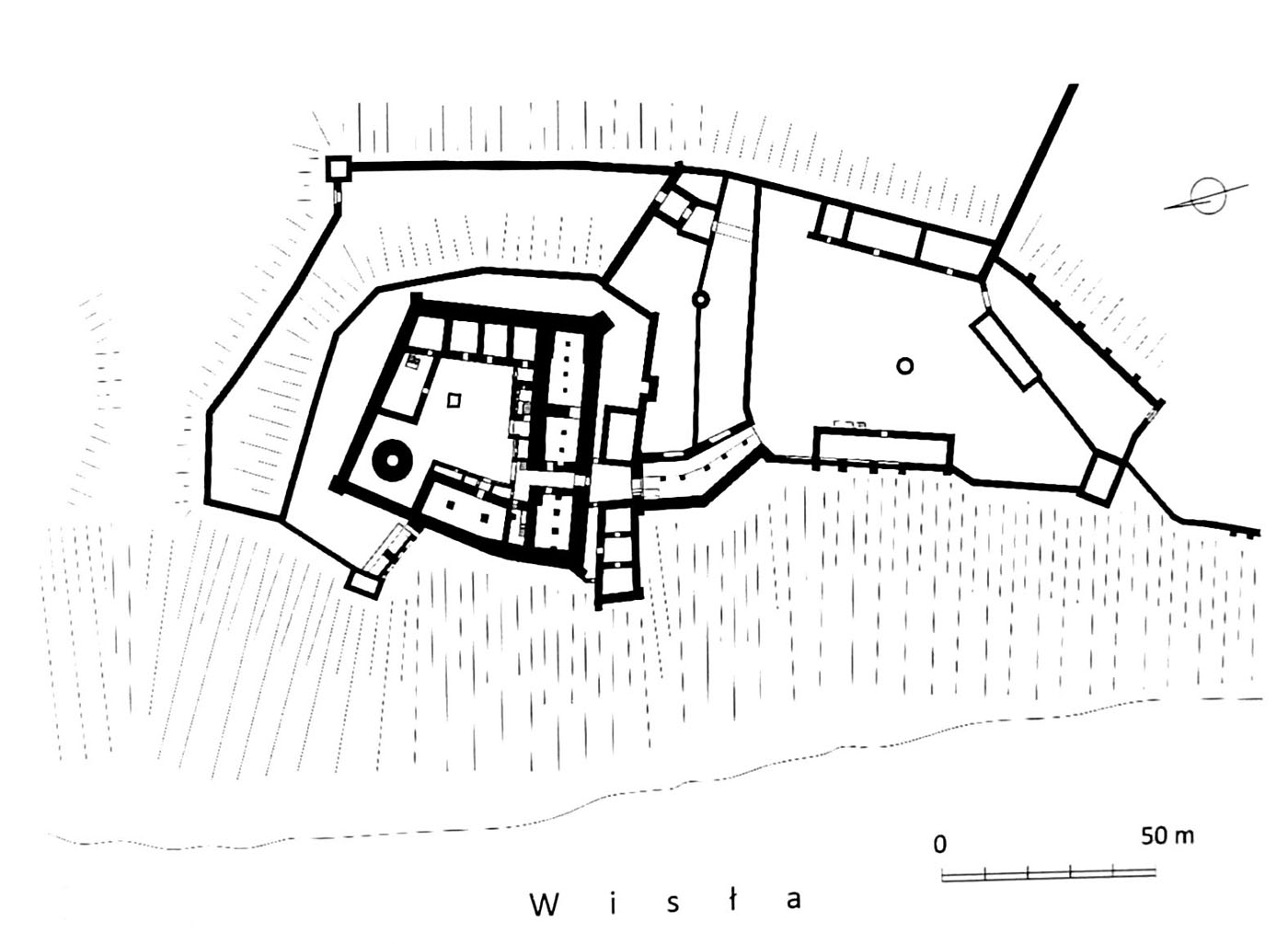

The castle was built on a hill with dimensions of approximately 160 x 70 meters, of 60 meters high slopes on the west side, descending to the Vistula river, separated by ravines and artificial ditches from the neighboring hills. On the eastern side, the area was lower, creating wet meadows that were difficult to cross in the spring and summer. There was also Lake Tuszewskie, where the Teutonic Knights mill operated. From the north, the Osa River joined the Vistula, while in the south, the castle was adjacent to the fortified town.

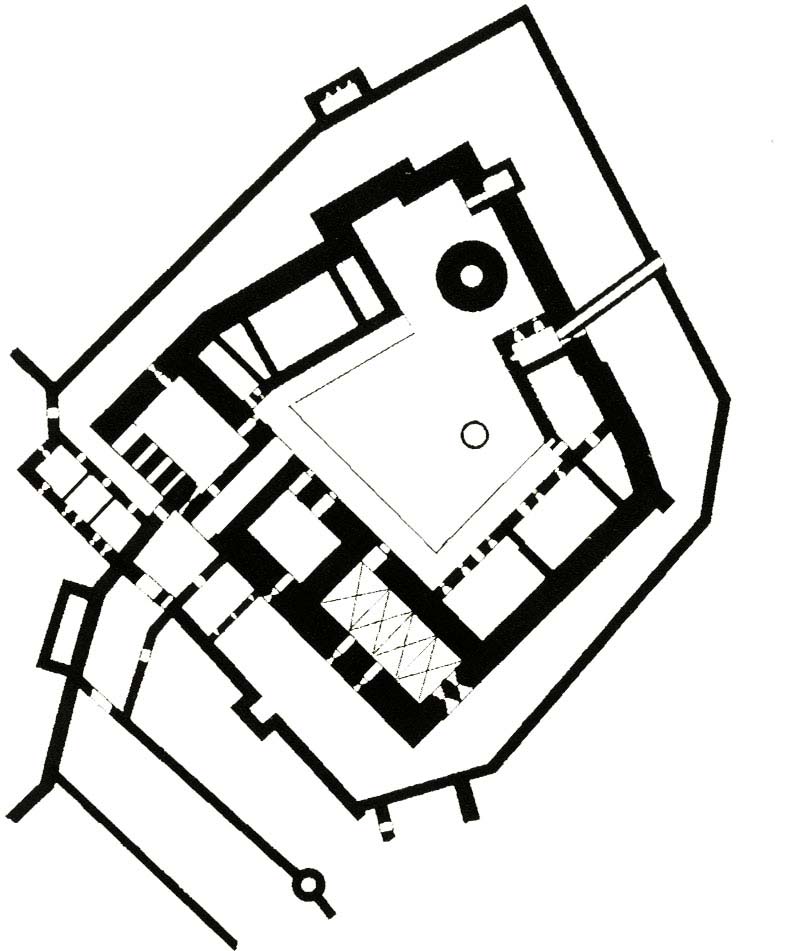

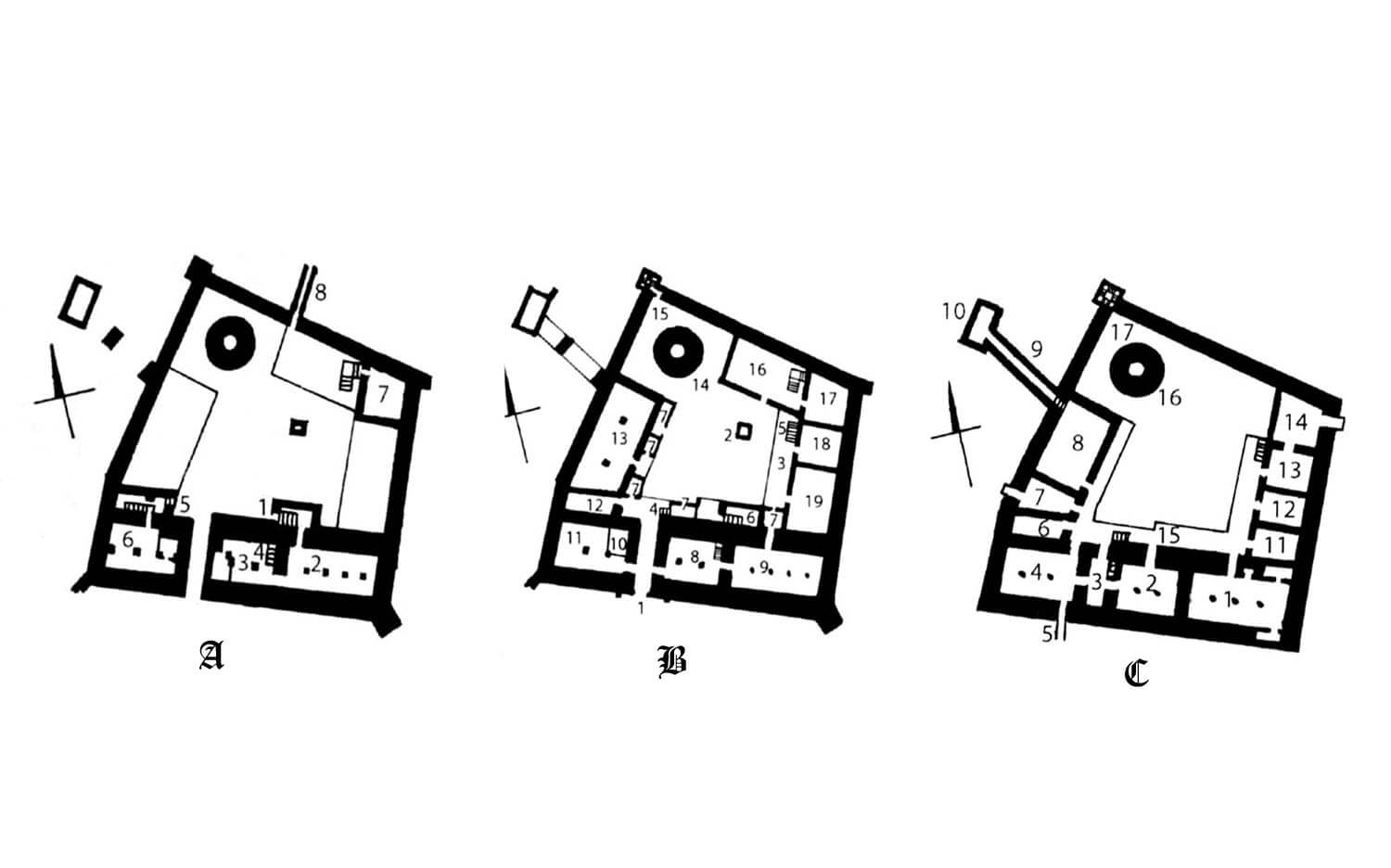

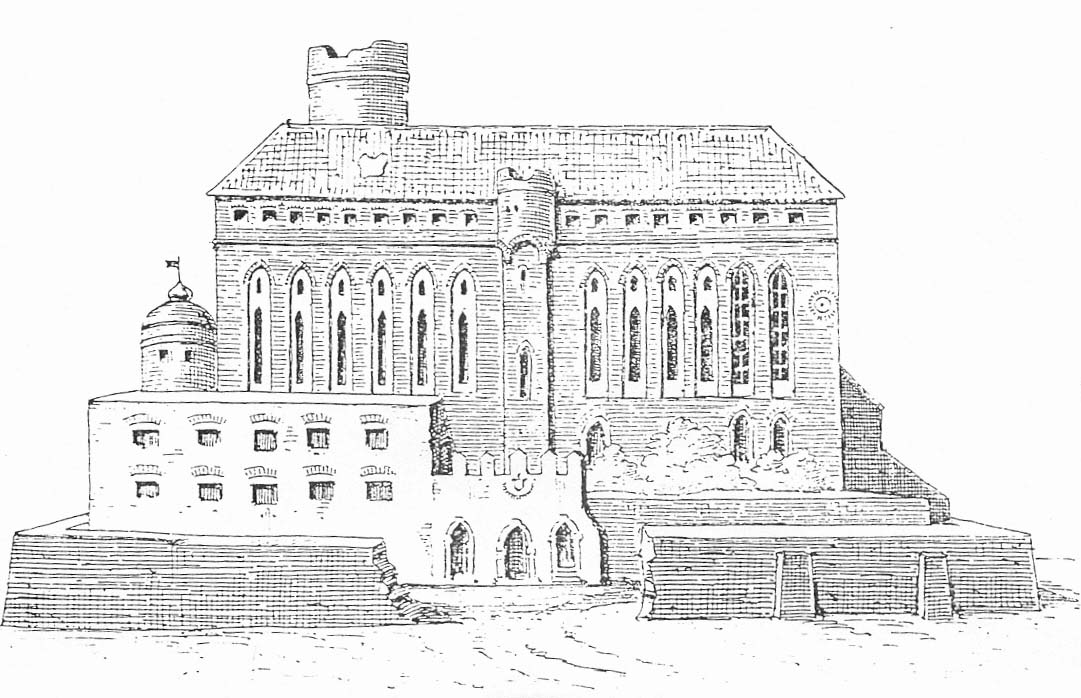

The main, highest part of the castle, which was the seat of the Teutonic convent, was built on an irregular, trapezoidal quadrilateral plan with side lengths: southern 55.4 meters, western 61.2 meters, northern 48.2 meters and eastern 44 meters. Four wings surrounded a paved courtyard with a well, while in the north-west corner there was a round tower, later called Klimek. It was free-standing, without connection to the neighboring northern and western wings, and also not connected to the two curtains of the defensive wall running nearby. These curtains met in the north-west corner, where a slender square tower was placed. The dansker on the western side could also have had a tower-like form, built on the slope of the Vistula hill, connected to the western wing by an arcade porch. The porch was probably supported by one four-sided pillar and one half-pillar at the wall of the western wing.

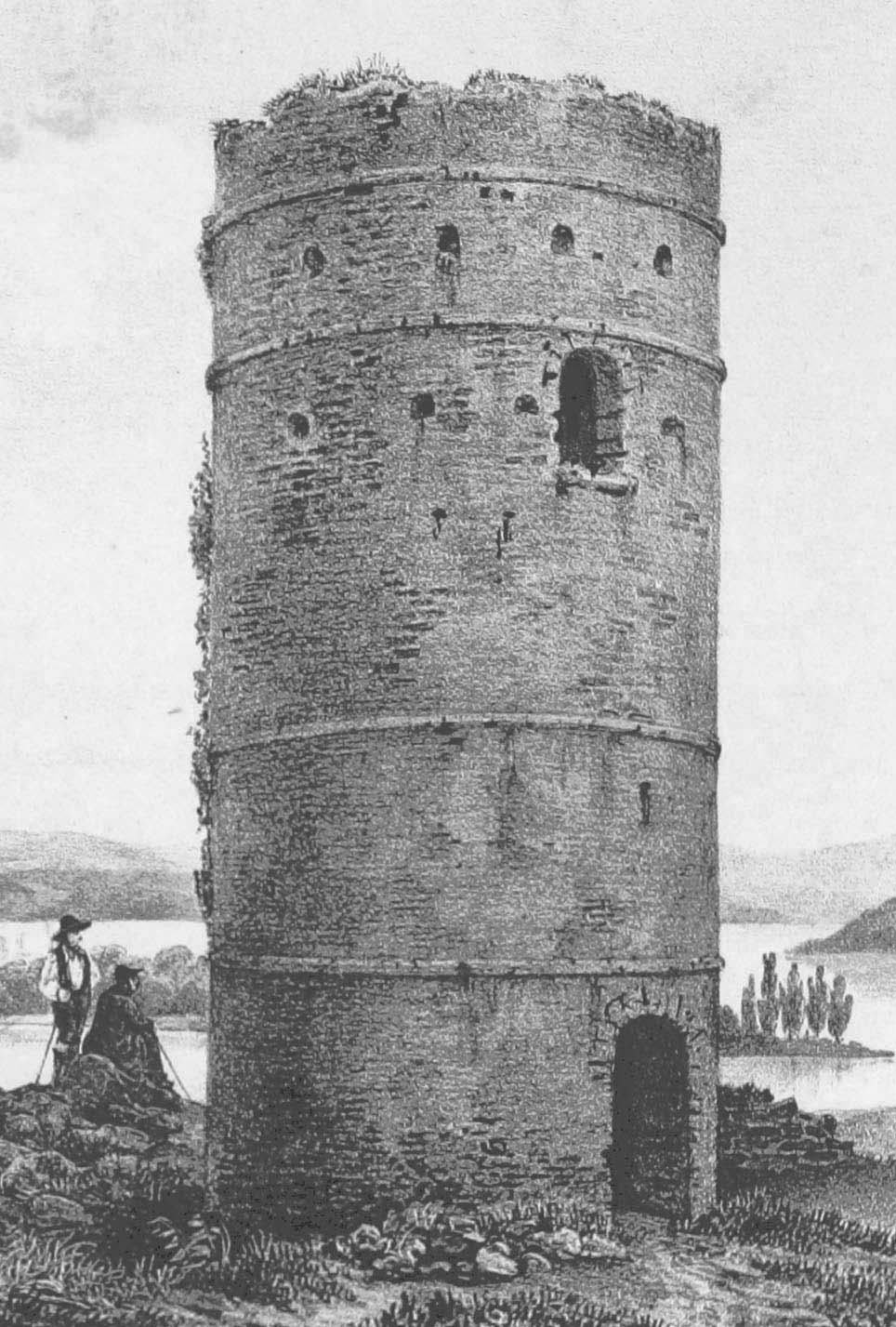

The main tower served defensive, observation and prison functions. Its height was about 30 meters and its diameter was 8.9 meters. The entrance to it was located 14 meters above the level of the courtyard. It led from the defensive walk of the western wing through a drawbridge. On the external walls, the tower was decorated with glazed bricks, in the form of alternating strips of natural and green-glazed bricks. It was a unique form of decoration in the Teutonic state. The tower was crowned with a battlemented parapet, perhaps mounted on consoles forming machicolations.

The circular interior of the tower on the ground floor was topped with a dome vault at a height of approximately 13 meters. This high and dark chamber, ventilated by a single duct and illuminated by a small opening, was probably intended as a pantry or a prison cell. Above, in addition to the central, circular chamber, there was a vestibule with an entrance, built on a rectangular plan in the thickness of the wall. Connected to it was a spiral staircase, also created in the thickness of the wall, leading to the upper floors. On the second floor, a round chamber with a diameter of 2.5 meters was equipped with a pointed entrance portal, four wall recesses with pointed arches and a slit opening, splayed into the interior. This floor and one or two floors above may have already been covered with ceilings.

The main and oldest, three-story castle wing was built from the south. There was a gate passage on the ground floor, perhaps protected by a defensive bay suspended on the top floor and towering over the entrance. The gate was certainly preceded by a foregate, running across the zwinger. Above the utility ground floor, in the southern wing there was a refectory from the west, a representative chamber (perhaps the second refectory, once considered a chapter house), a narrow intermediate room separating them, and in the eastern part the chapel of the Virgin Mary. The latter was probably three-bay, vaulted, measuring approximately 8 x 16 meters, with a sacristy at the chancel part. Its furnishings included stalls, marble figures and three altars. The wing also had a third, low storey for storage and defense functions, as well as basements on both sides of the gate passage. The basement chambers had two aisles, separated by granite pillars. The southern facade of the southern building was divided by ogival blendes with windows embedded in them on the main and upper floors, which was a characteristic feature of the castle.

The western wing at the first floor level was intended for the commander’s apartment and guest chambers, with access to the latrines in the dansker protruding on the arcades towards the Vistula. According to medieval customs, in the west wing the ground floor was probably intended for economic functions, while the attic was for defense and storage purposes (granary). On the eastern side of the courtyard there was a brewery, a bakery and a dormitory, but these rooms were probably originally lower than the adjacent curtain of the defensive wall. In the second half of the 14th or at the beginning of the 15th century, a single-story, brick economic building was built along the northern curtain with a canal running under the northern zwinger, discharging waste from the castle kitchen. The kitchen was located in the northern wing, where from the east it was adjacent to a barrel-vaulted room with a basement. The buildings in the northern part of the courtyard in the Teutonic times were probably of different heights, without a main residential floor.

Buildings from the side of the inner ward were connected with brick cloisters. From the outside the whole was surrounded by a second perimeter of the wall. It was quite irregular, adapted to the terrain, which meant that the width of the zwinger was varied. After the western slope slid to the Vistula in 1388, the zwinger wall was not rebuilt here, but the dansker (latrine) was erected again and the half-timber building on the brick foundation under its arcades was also built. Its function is unknown. In the southern section of the outer wall, the most important for defensive purposes, there was a rectangular half-tower, fully protruded towards the slope of the hill.

From the north, south and east sides, the upper castle was surrounded by outer baileys. The most extensive and oldest of them, created in the first half of the fourteenth century, protected by a four-sided tower, was located on the south side. At the eastern and western curtains there were two oblong economic buildings on it. The southern outer bailey was connected with the eastern ward by the Fijowska Gate complex. Pressed between the perimeter wall and the wall of the lower zwinger, this gate had an unusual arrangement – the gatehouse tower was located near the curtain, and the foregate from the side of the southern ward. The southern bailey was connected with the upper ward through a bridge, based on one side on the pillars, and on the other side on the wall of the entryway. Bridge was led over the moat and zwinger, additionally protected by a cylindrical tower, located in the line of the defensive wall separating the baileys. The northern bailey also had a tower, built in the north-east corner. It had a four-sided form, partially protruding in front of the adjacent curtains, thanks to which it could flank the gate located next to it.

In the second half of the fourteenth century, in the south-west corner of the zwinger of the upper castle, the commander’s house was erected. Probably a little later south of the entrance gate, also next to the zwinger wall, another brick building was erected. The commander’s house was a one-story structure with three rooms from which the extreme western one was equipped with a latrine, most likely in the form of a protruded overhanging bay.

Current state

The castle in Grudziądz, apart from the small relics, has not survived to our times. In recent years, a new Klimek Tower has been built, but it is not a true replica, but only a brick and concrete viewing platform. The remains of the southern wing basements with fragments of the staircase connecting the basement with the courtyard and fragments of the eastern part of the gate’s neck have survived from the original parts of the castle. On the west side of the gate passage, a cross-vaulted cellar, another staircase and stone pavement were discovered. No traces of the curtain walls of the northern and western wings have survived, as this part of the hill has been completely leveled. In the area of the former zwinger, the remains of the so-called commander’s house have been discovered. The figures from the castle chapel were later built into the tower of the Grudziądz church of St. Nicholas.

bibliography:

Atlas historyczny miast polskich. Tom I Prusy Królewskie i Warmia, red. A.Czacharowski, zeszyt 4 Grudziądz, Toruń 1997.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Torbus T., Zamki konwentualne państwa krzyżackiego w Prusach, Gdańsk 2014.

Torbus T., Zamki konwentualne państwa krzyżackiego w Prusach, część II, katalog, Gdańsk 2023.

Wasik B., Budownictwo zamkowe na ziemi chełmińskiej od XIII do XV wieku, Toruń 2016.

Wasik B., Grudziądz – Zabudowa zamku górnego i przedzamczy na podstawie źródeł pisanych i ikonograficznych z XVI-XVIII wieku [w:] Zamek w Grudziądzu. Studia i materiały, red. M. Wiewióra, Toruń 2012.

Wiewióra M., Stan badań archeologiczno – architektonicznych nad zamkiem krzyżackim w Grudziądzu [w:] Graudentum. Studia z dziejów Grudziądza i okolic, tom 1, Grudziądz-Toruń 2020.