History

The construction of the church and the Franciscan friary began at the turn of the third and fourth quarter of the thirteenth century, on the initiative of prince Bolesław the Pious and his wife Jolenta, although the first Franciscans were able to preach in Gniezno from around 1259. The construction works were probably interrupted by the death of the founder in 1279, but soon after were resumed at the initiative of prince, later king Przemysł II, at the time of which the construction of the monastery of Poor Clares began. Duchess Jolenta was supposed to find shelter there, which is probably why work on the female part of the complex with the nuns’ oratory was given priority. It was ready as early as 1283, and Przemysł II endowed the friary in 1284 and 1295. Although he continued the work of Bolesław, he made such an important contribution to the founding of the monastery that his contemporaries considered him the founder. Władysław the Elbow-high in the act of granting from 1298 stated that “the monastery had been built by Przemysław the Polish king”.

In 1303, the deceased Duchess Jolenta, who entered the convent of Poor Clares before her death, was buried in the church. Her daughter Jadwiga, who stayed with her mother in Gniezno until 1293, became the wife of king Władysław Łokietek, and another daughter, Elżbieta, was the wife of Henry V the Fat, the prince of Wrocław and Legnica. At the end of the thirteenth century, a representative of the Silesian Piast line, daughter of Henry V the Fat, and granddaughter of Jolenta, Helena, was also in the Gniezno convent. Thanks to this, the friary had rich and influential donors who contributed to its expansion. Around 1295, in addition to the oratory and the building of the Poor Clares, the chancel of the church was completed, and probably also part of the Franciscan claustrum, because that year a provincial chapter was to be held in Gniezno. Then construction started of the nave of the church and other residential and economic buildings, completed by the end of the 20s of the 14th century.

In 1331 the friary complex survived the devastation of the town by the Teutonic Knights. At that time, some of the town’s inhabitants were to take refuge there. Better times for the town and the monastery came in the second half of the 14th century. In 1372, abbess Przechna obtained a document from the queen of Poland and Hungary, Elisabeth, confirming earlier grants to the friary. Przechna was recorded as an abbess in 1404, and it was probably due to her long office related the construction of the chapel at the oratory, with a vault modeled on the chapels of St. Mary’s from Kraków and Wrocław cathedrals. It was a testimony to the high ambitions of the founder. Next, in the years 1409 – 1418, under Katarzyna Zagajewska, brick monastery buildings, a bathhouse, a kitchen and a monastery brickyard were erected, and two rooms were to be renovated.

In 1519, the church suffered damages during a great fire of the town, including the collapse of the vaults over the nave, the chapel of Poor Clares and partly over the western bay of the chancel. The southern chapel was destroyed and it was not rebuilt later. The scale of the damages was so large that the repairs dragged on for many decades, despite the fact that the 16th century was the period of the greatest economic boom for the town, in which the St. Adalbert fairs were visited by merchants from all over Europe. The slow reconstruction could have been influenced by the crisis in the order itself, the spreading ideas of the Reformation, and thus the reduced number of people willing to enter the novitiate. Even during the account from 1596, the vault over the nave of the church was described as destroyed, only the defects above the chancel were replaced.

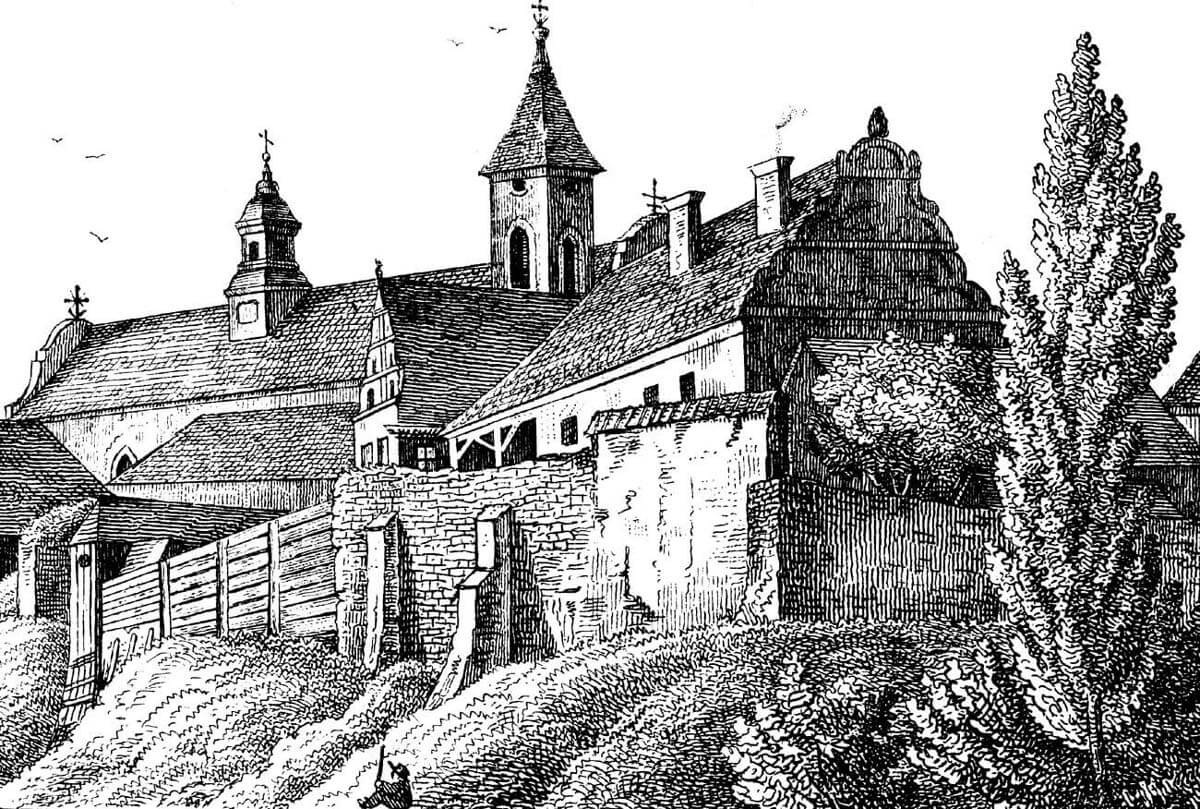

Church and friary buildings burnt again in 1613. After rebuilding and especially after a thorough reconstruction in the second half In the 18th century, they lost many of their original style features. In 1836, the Prussian authorities closed the Franciscan monastery, a year later the same fate affected the Poor Clares. The Franciscan monastery was occupied by the army, and the Poor Clares house was demolished at the turn of the sixties and seventies of the 19th century. The Franciscans returned to their former seat in 1928. In the years 1930-32 they carried out the restoration of the temple, restoring it in part to Gothic forms.

Architecture

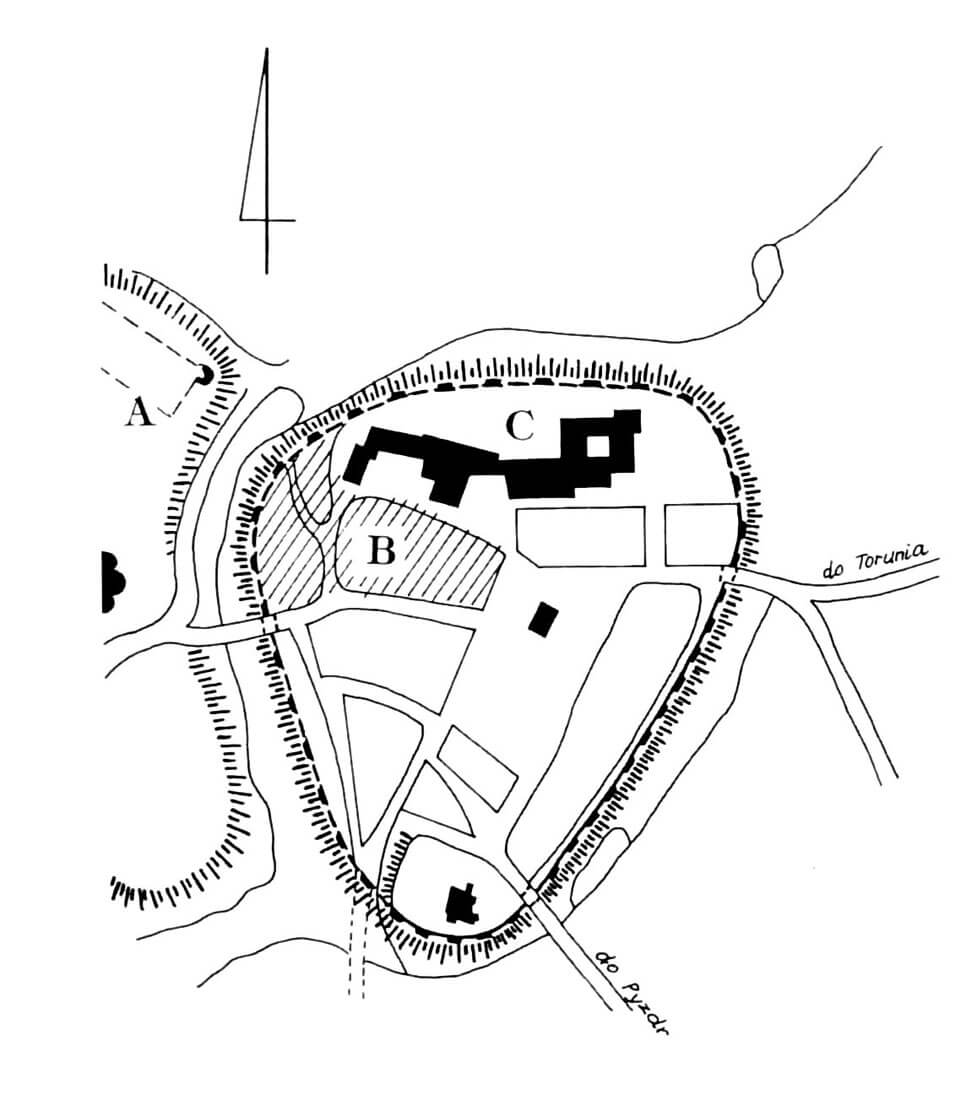

The friary was situated in the northern part of the town, on the hill called Panieńskie, in close proximity to the town’s defensive walls. It was located between the market square on the south (separated by a plot of bourgeois buildings through which a short street led) and the valley of the Srawa river on the north side, behind which the church of St. John was situated. From the west, a ravine with a flowing stream separated the town from the cathedral hill. The Jewish quarter bordered the friary complex from the south-west.

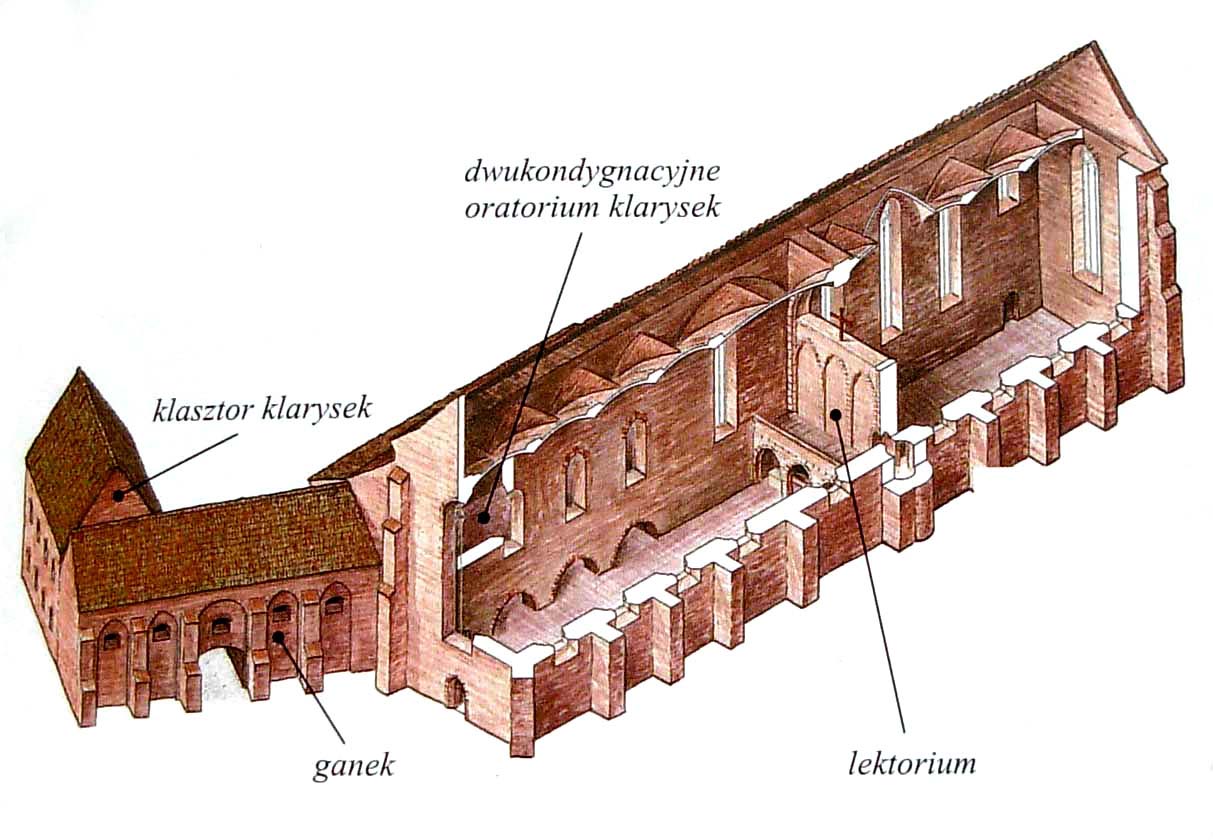

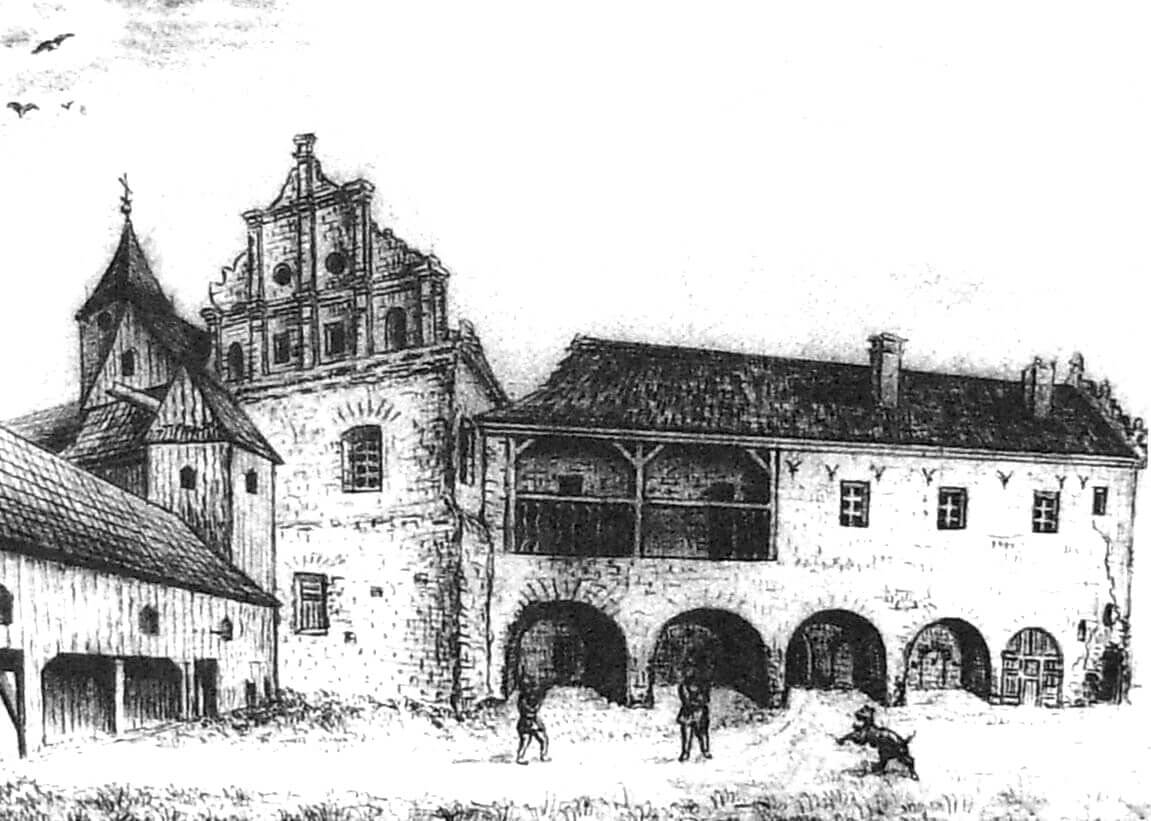

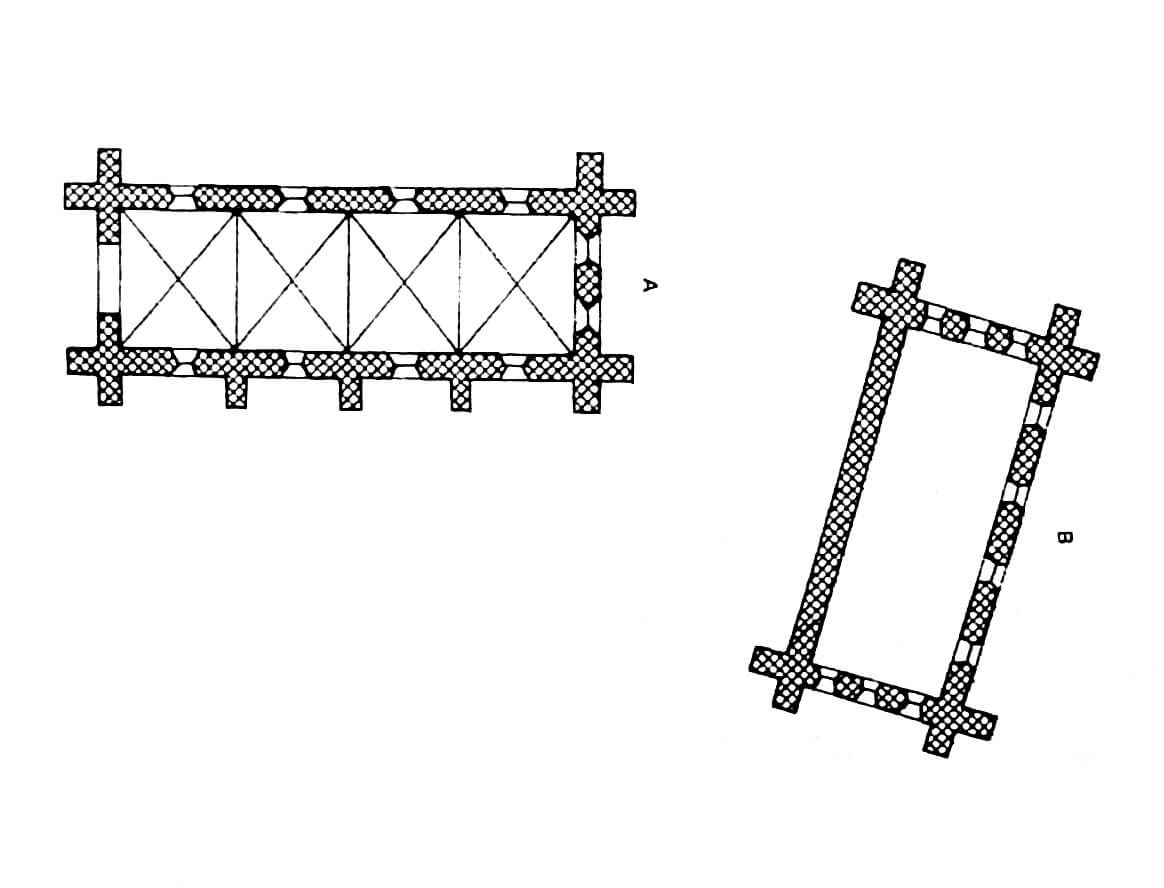

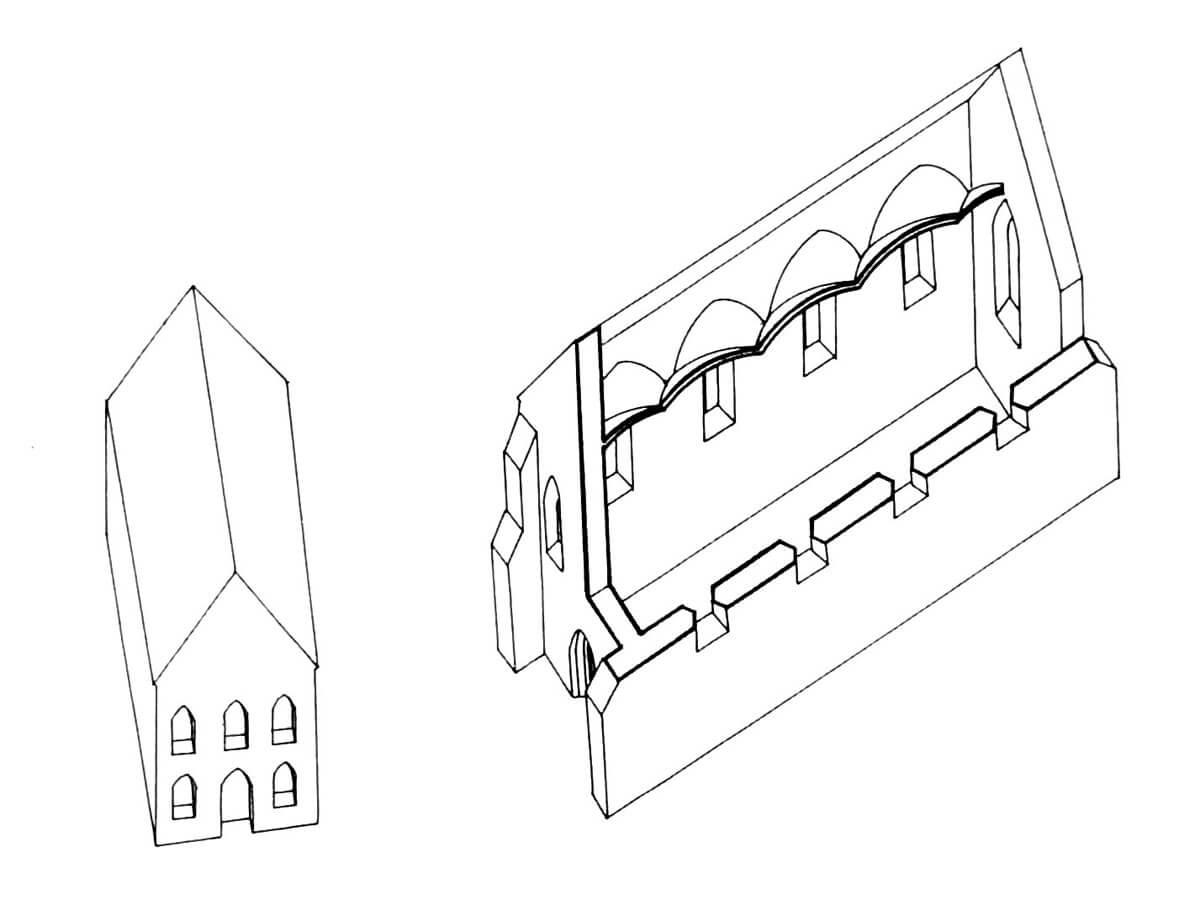

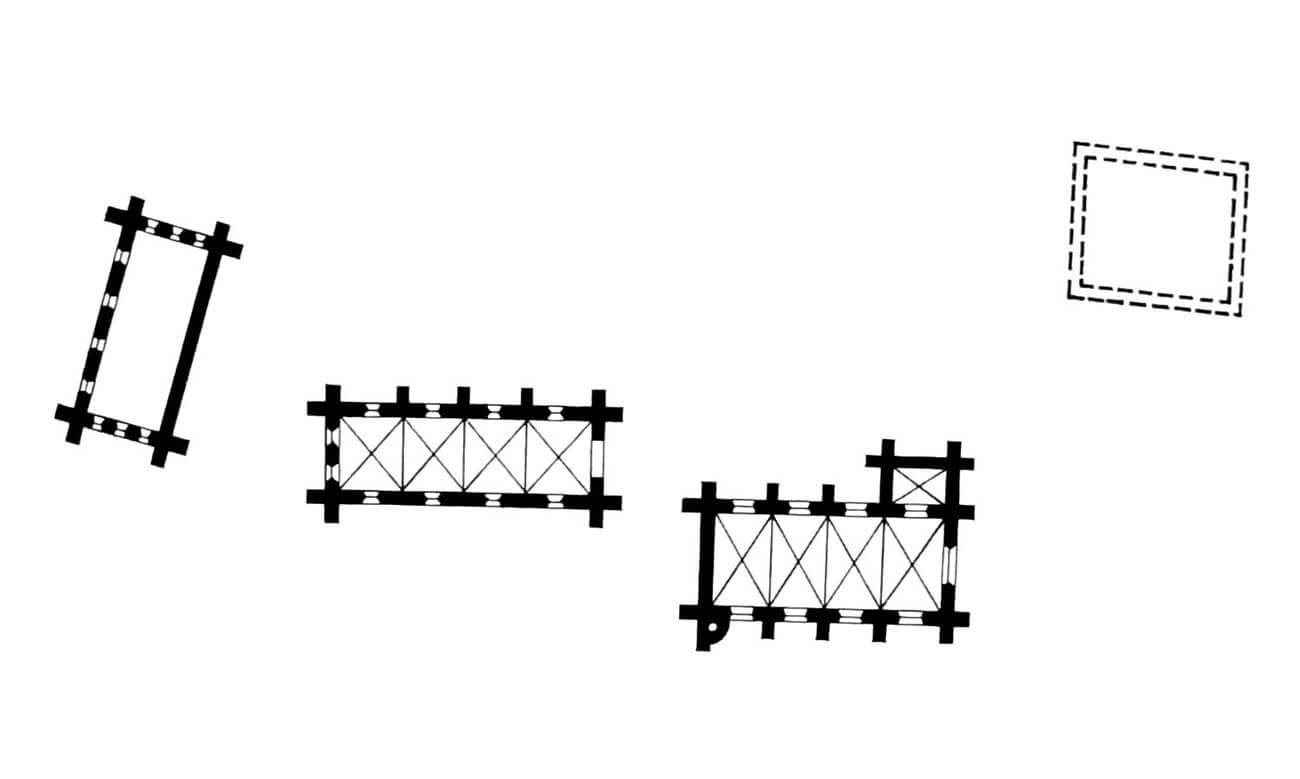

The complex consisted of the church and the Franciscan friary buildings on the north side of the chancel and the Poor Clares building on the north-west side of the nave. The monastery church was connected with the Poor Clares building by a brick, five-bay, 5.5-meter-wide porch, fastened on both sides with double-stepped buttresses and covered with a gable roof. In its middle bay there was a wide passage leading from the oratory to the friary gate. In addition, the southern facade of the porch was decorated with high, pointed recesses in which small windows were pierced. In the fifteenth century, the house of Poor Clares was extended from the south by a perpendicular Gothic wing, and from the north by another wing parallel to the older one.

The early-Gothic church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary was built as an aisleless structure with a younger five-bay nave 8.1 x 31.5 meters, and an older, elongated, four-bay chancel with dimensions of 8.1 x 20.5 meters, built on a rectangular plan of the same width and height as the nave. At an early stage, the construction of a transept was also planned, but after the foundations were created, the idea was abandoned. Only a trace of it remained in the unusually different shape of the eastern bay of the nave, created on a square plan. On the northern side of the nave, a two-level, four-bay oratory of Poor Clares was added, which was originally a free-standing structure before the church was completed (probably, however, from the beginning it was planned to connect the building with the church, because the southern wall of the oratory was devoid of buttresses). Over the nave and chancel there was a common gable roof based on triangular, probably decorated gables, and the oratory was covered with a mono-pitched roof.

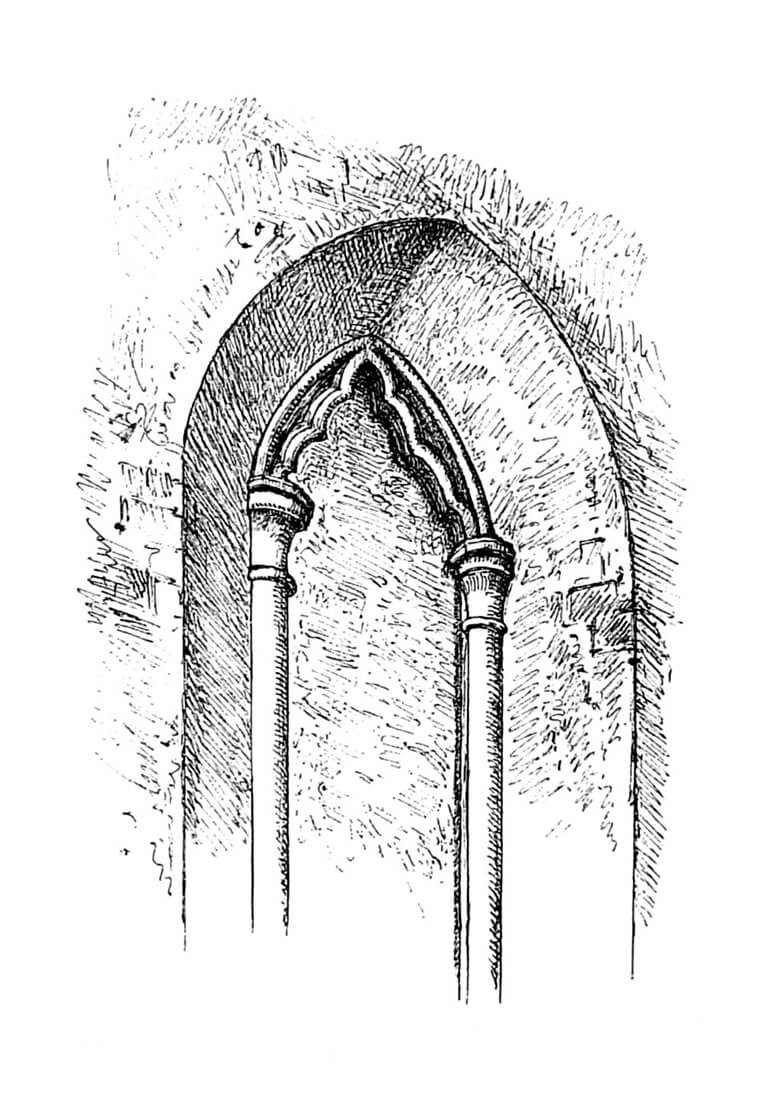

The oratory was illuminated from two sides by four narrow, high and strongly splayed pointed windows. They were filled with traceries with arcades, which were rarely seen three times, and were based on shaft jambs with chalice capitals and probably plate bases. In the west façade there were two symmetrically arranged, strongly splayed on both sides, narrow windows. The eastern wall probably had one large window, while the entrance was hypothetically located on the ground floor of the central part of the western wall.

The church on the outside was clasped with buttresses, in the western corners of the nave situated at an angle, and in the eastern corners of the chancel located more archaically, perpendicular to the axis. Narrow, pointed-arched windows were pierced between the buttresses, with a distinctive large eastern window of the chancel, filled with a three-light tracery. The windows in the side walls of the chancel were two-light, slender, and significantly splayed. Their early-Gothic openings from the end of the 13th century were equipped with bases, and therefore probably also with shafts and heads, as well as the windows of the oratory. In the northern wall, under a slightly shorter window, there was a portal leading to a low sacristy. The shape of the windows in the southern wall of the nave was similar to chancel openings, but their stone jambs were devoid of bases and capitals, and ended with trefoils at the top. Probably a slightly larger window was pierced in the west facade, where the main entrance portal must also be located.

All the bays of the nave and the chancel had a progressive plan of a rectangle transverse to the axis of the church, with the exception of the aforementioned last bay of the nave, which was erected on a square plan. The chancel was topped with an early-Gothic cross-rib vault, supported on consoles in the form of elongated chalices, without shafts (the first such example in Greater Poland region), but it is not known whether the nave was originally covered with a vault or only a timber ceiling. The cross-rib vault in the nave was founded at the latest in the late Middle Ages, but at the beginning of the 16th century it was destroyed.

After the nave of the church was built, a gallery was erected for the nuns on the first floor of the oratory. It was open to the nave with windows, while in its ground floor there was a mortuary. Perhaps its four ogival arcades were connected with the nave, or perhaps it was only one arcade leading to the eastern bay of the oratory (where Duchess Jolenta was buried in 1305). The chancel was separated from the nave by a rood screen, consisting of a screen wall and a tribune supported by columns, open to the nave with arcades. The entrance to the first floor of the rood screen led through a vaulted passage from the southern, cylindrical stair turret added to the extreme, western bay of the chancel. This would indicate a great height of the rood screen, reaching the base of the ogival arch of the chancel arcade. The eastern bay of the nave, wider than the other ones, allowed for the tribune to be extended to the west. Its base was probably a tripartite, columned hall, covered with a cross-rib vault, equipped in a central bay with a passage from the nave to the choir (probably with altars in the side ones). At a height of about 3-3.5 meters, there must have been some form of balustrade closing the tribune.

Under the chancel there was a crypt, an underground part of the church, not brightened by sunlight, with an area almost identical to the presbytery part. Its interior was originally single-space, covered with groin or rib vaults supported directly on the perimeter walls, probably similarly arranged as the bays of the chancel, which would be supported by a wide entrance located in the western wall. This would cause a significant raise of the vault to about 2-2.5 meters, so it is possible that, according to the original plans, the crypt was supposed to have its own lighting and basically constitute the lower floor of the presbytery, but this intention was not implemented, possibly due to the death of the founder in 1279. Irregular pillars were introduced into the buried or provisionally completed crypt only at the end of the Middle Ages and a low barrel vault was than established.

In the second half of the fourteenth century, difficulties in the visual contact of Poor Clares with the altar, participating in masses in the tribune of the oratory, contributed to the construction of a chapel measuring 6.4 x 7.4 meters, added to the oratory from the east, and to the extreme bay from the north side of the nave. The chapel was covered in the western bay with a cross-rib vault, and in the eastern bay with a three-support vault. Its lighting was provided by one window from the north and two from the east. Then, at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, another chapel was added to the church, situated on the south side of the eastern bay of the nave (it was erected on the foundations of the unrealized 13th-century transept). The new sacristy, built on the south side of the chancel, was needed due to the transformation of the old sacristy located on the north side, into a passage connected with a cloister and new claustrum buildings. The annex housing the new sacristy consisted of two rooms in the ground floor, it also had an upper floor with a semi-oval turret in the south-west corner, tucked between the buttresses. From the west in the fifteenth century, a four-storey, four-sided tower was added to the nave, covered with a tent roof, using as a base a porch connecting the Poor Clares building with the oratory.

The buildings of the Franciscan claustrum were located on the north and north-eastern side of the church chancel. The northern wing had a basement. Probably on the ground floor in the eastern part there was a refectory, situated in a room with an irregular, trapezoidal plan, protruding in front of the compact building block. The friary also had an east wing, but it could not have a west wing, that would interfere with the Poor Clares chapel at the end of the oratory with large, Gothic windows (or it was very short). The southern wing, created from the transformation of the old sacristy, served only communication functions.

Current state

The friary church was significantly transformed in the early modern period. This applies especially to the external façades, but also inside the oratory in the interwar period, the floor was removed and transformed into an aisle by cut large arcades in the wall. The rood screen was pulled down even earlier, and the chancel arcade changed appearance. The pseudo-Gothic vault of the nave was built in the years 1930-1932, but the original chancel vault has been preserved, currently supported on Baroque consoles (the original corbels have survived at the eastern wall). The chancel windows were partially transformed, especially the northern and eastern ones were walled up after the addition of early modern buildings. The southern ones have been preserved, but their traceries are reconstruction. Among the original windows of the oratory of the Poor Clares you can see one walled up and one rebuilt as a passage. Of the medieval Franciscan friary buildings, only the foundations and cellars remained, on which a new monastery complex was erected in the 18th century (possibly the Gothic walls are also hidden under early modern plasters). The nunnery buildings of Poor Clares were completely demolished in the 19th century.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Kowalski Z., Gotyk wielkopolski. Architektura sakralna XIII-XVI wieku, Poznań 2010.

Maluśkiewicz P., Gotyckie kościoły w Wielkopolsce, Poznań 2008.

Pasiciel S., Zespół klasztorny franciszkanów i klarysek w Gnieźnie, Gniezno 2005.

Tomala J., Murowana architektura romańska i gotycka w Wielkopolsce, tom 1, architektura sakralna, Kalisz 2007.