History

The first record of St. Mary’s parish in Gdańsk appeared in a document from 1240. It is known thanks to that fact that there was already functioning St Mary’s Church, chronologically the third oldest sacral building in Gdańsk, after the Old Town parish church of St. Catherine and the Dominican church of St. Nicholas. It is not known when exactly it was built, although there is a chronicle mention that in 1243 it was to be founded by the Pomeranian Prince Świętopełk in honor of his mother, who died three years earlier. The first certain information about the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary appeared only in 1271 in the document of Prince Mestwin. It recorded three groups living in Gdańsk: German townspeople, Prussians and Pomeranians, while St Mary’s church was most likely connected with German merchants, for which the Main City of Gdańsk was established.

After the conquest of Gdańsk in 1308 by the Teutonic Order and the destruction of the old stronghold of Gdańsk, the merchant city with German patriciate entered a period of intense economic development, which also influenced the development of St. Mary’s church. Its rebuilding, and in fact the construction of a new Gothic building, began thanks to a privilege issued in 1342, granted to the Main Town of Gdańsk by the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Ludolf König. It introduced numerous regulations important for the development of the city, and regarding the church, it gave the parish priest a rent-free land and marked out an area for the temple and the adjacent cemetery, which were to be remote from other secular buildings. It was important in connection with the more and more intensive development of the rapidly growing city and the threat of taking the church grounds by private houses (the old church, if it stood in the same place, was probably a small building).

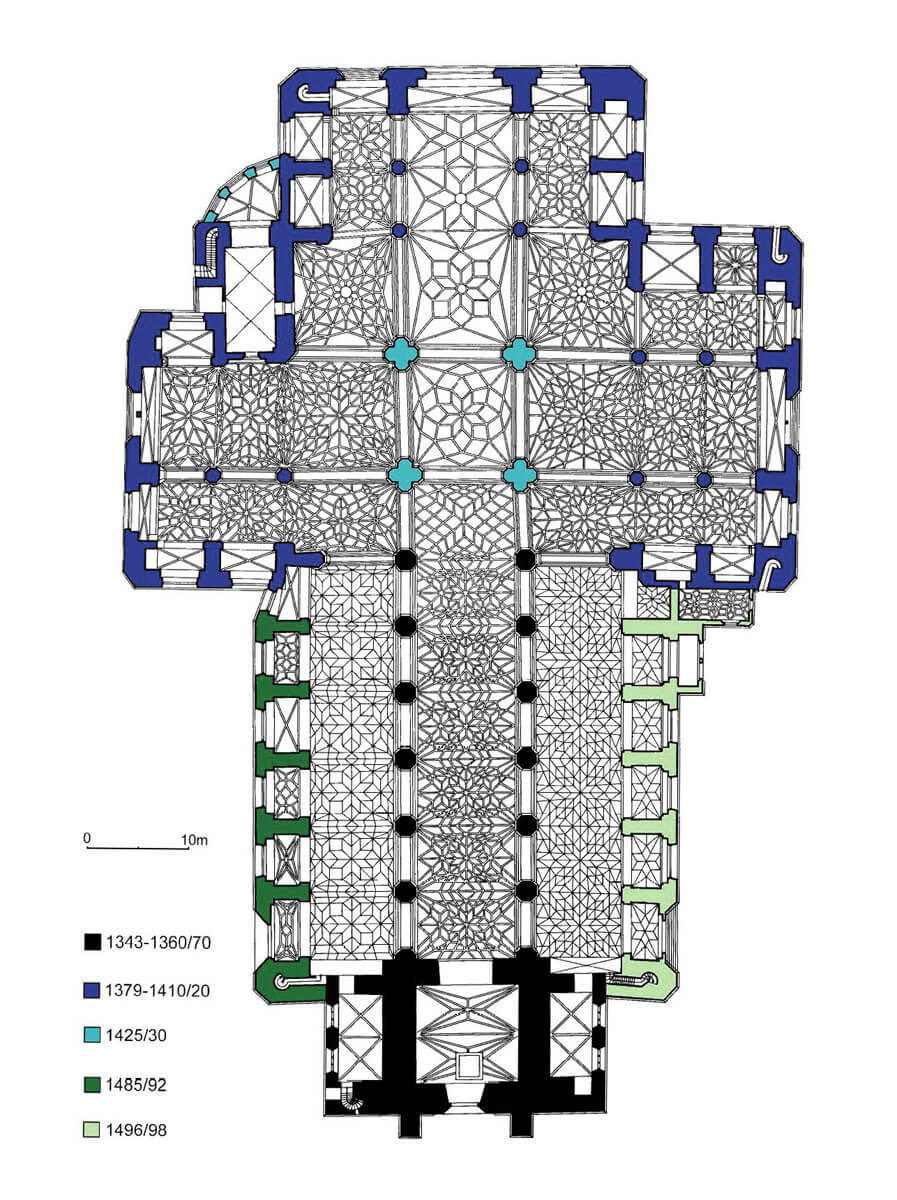

Construction works on the new church began in 1343, a few months after the privilege was issued. Their financing was the responsibility of the townspeople (from free donations, gifts and indulgences), while city councilors were responsible for organizing the construction. Within 15 years, the chancel and the central nave were built, and then the tower was erected. The Teutonic Knights ordered it not to exceed the height of the tower of their Gdańsk castle. An under-tower porch was also added, where beggars and the sick were sheltered during bad weather, but in 1363 the Teutonic commander ordered them to be expelled from the vestibule, probably due to fear of infecting the richer faithful. Finally a basilica was created with a high central nave and with a presbytery that was probably straight ended, which was equipped with altars, chapels and bells until the 70s of the 14th century.

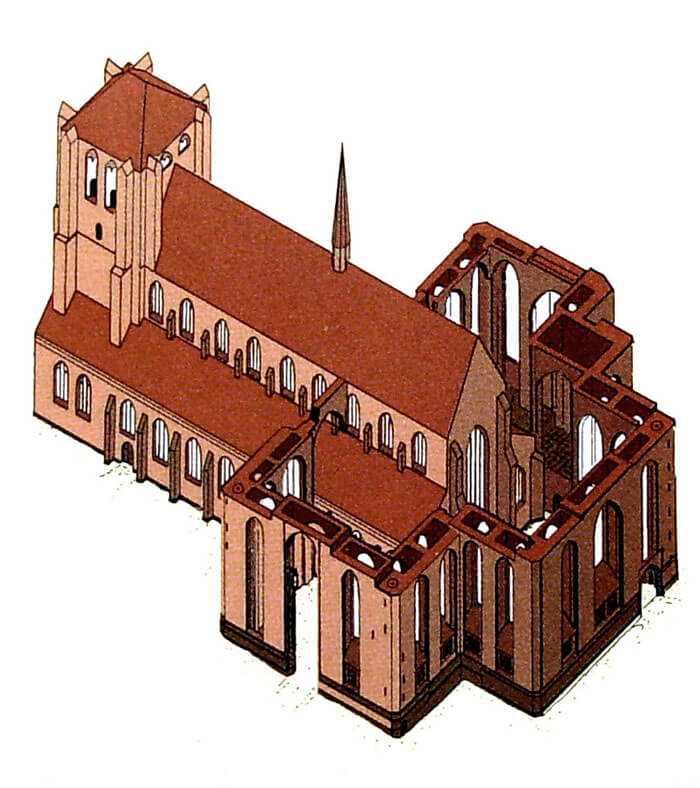

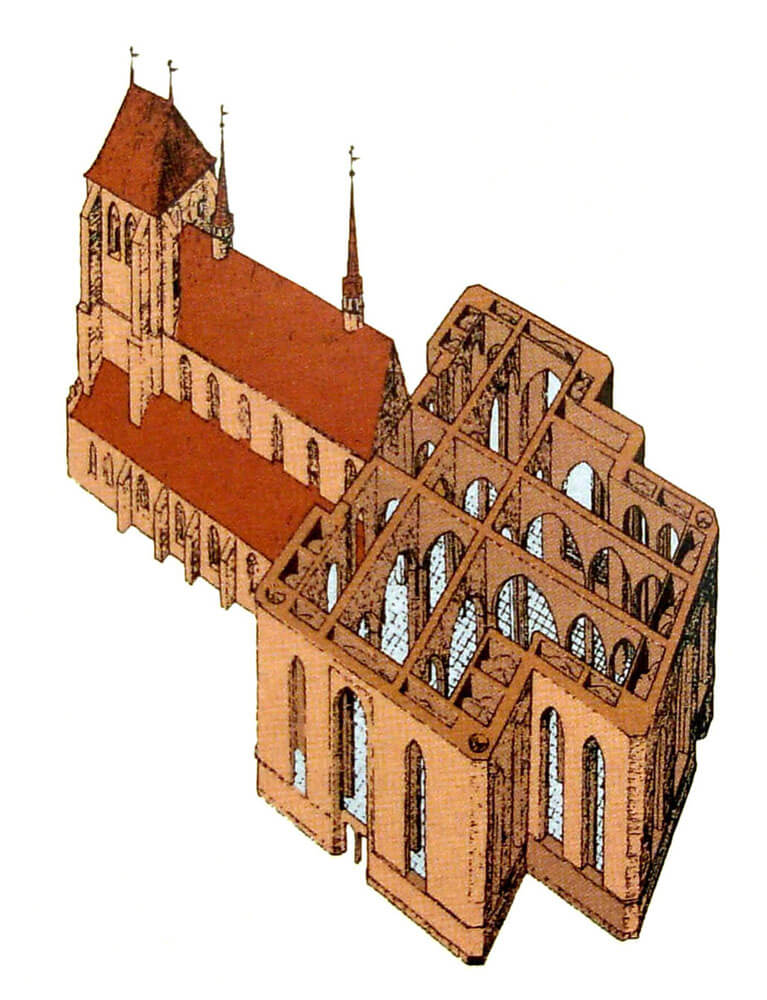

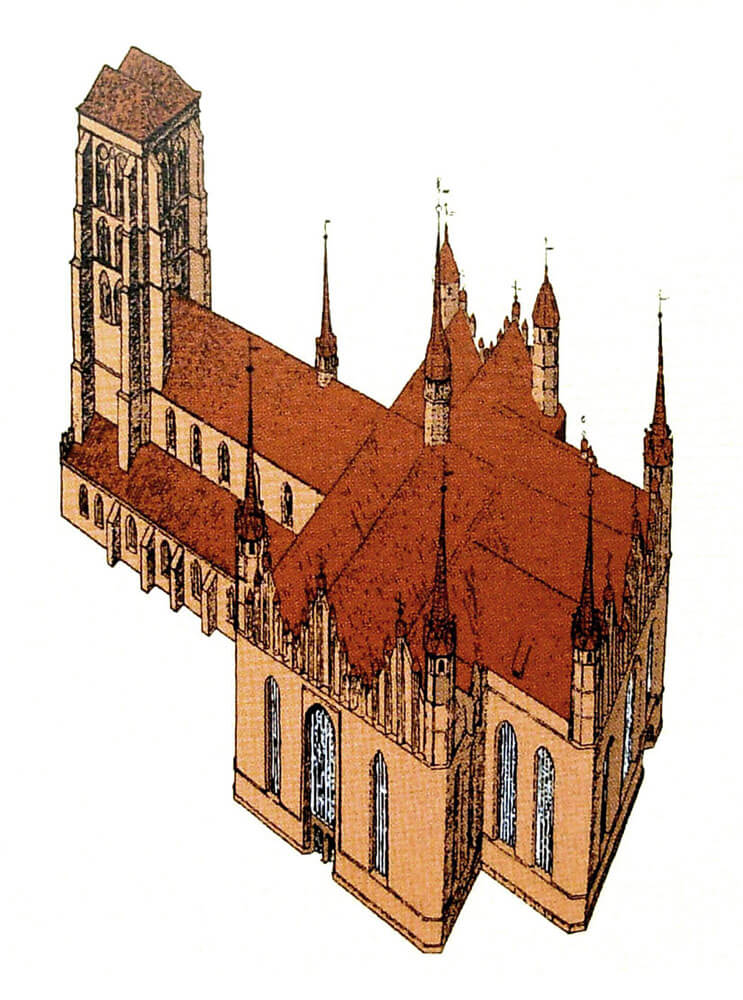

Soon after the basilica was completed, around 1370, the city council decided to enlarge the church considerably. It was decided to build a huge chancel and a transept on the eastern side, on the building of which an agreement was signed with the master bricklayer, Henry Ungeradin, who at that time was in charge of the construction of the Gdańsk Main Town Hall. By 1410, external walls were erected up to a height of 25 meters. However, the building did not have any roof, and the chapels inside were protected by makeshift structures. Presumably inside the new walls there was still an old chancel, which was still in use. The war with Poland in 1410 delayed further construction. It started only in 1425 under the direction of master Claus Sweder. Around 1430, the walls were completed, and in the years 1445-1447 all the roofs were installed. The result of this stage of works was the disturbance of the church architecture due to too large disproportions between the nave, tower, and the chancel. For this reason, between 1459 and 1466, during the prolonged Thirteen Years’ War, the tower was raised by two storeys. Only then did it begin to be visible from the sea, becoming a landmark for sailors. The last stage of work was to adapt the size of the nave to the rest of the temple, as a result of which it was to be significantly enlarged. The works started in 1484, interrupted in the following years by construction disasters. From 1485, work was led by the new master mason, Hans Brand, who replaced the earlier Michael, but as soon as he laid the foundations for the new walls, the wall of the old nave collapsed. Henry Hetzl, another masonry master, imposed a very fast pace of work in the years 1496-1498, which probably caused one of the pillars to collapse as a result of a rush, which caused the adjacent part of the walls also to destroy. The construction, however, continued until the last vaults of the church were solemnly laid in 1502 and the 159-year-old construction was completed (the vault at the crossing was founded by Henryk Hetzl himself).

A dozen or so years after the completion of construction, the Reformation reached Gdańsk, and the church was taken over by Protestants. The former medieval layout was preserved and no structural changes were made, only the decor was changed in accordance with the doctrines of Martin Luther, and the walls covered with polychromes were then whitened. When Catholics left the church, indulgences and funeral masses ended, and private chapels lost their functions. Fortunately, there were no acts of vandalism, iconoclasm, or sale of inventory, at best, with time, individual altars disappeared. On the other hand, there were numerous, early modern tombstones of Gdańsk patricians and merchant families added.

In the 19th century, plans were made to renovate the church, but due to lack of funds, they were not carried out to a greater extent. The first tap of more serious repair work began between 1928 and 1941, with the main emphasis on a cracked tower, strained after 250 years of bearing the giant bells. The Second World War brought great damages. The wooden structures of the roofs burned down, part of the vaults collapsed, some bells melted, some equipment was destroyed or scattered. In 1946, the interior was cleared of rubble, secured and gradually rebuilt. The salvaged equipment returned, and fragments of Gothic polychrome were also discovered.

Architecture

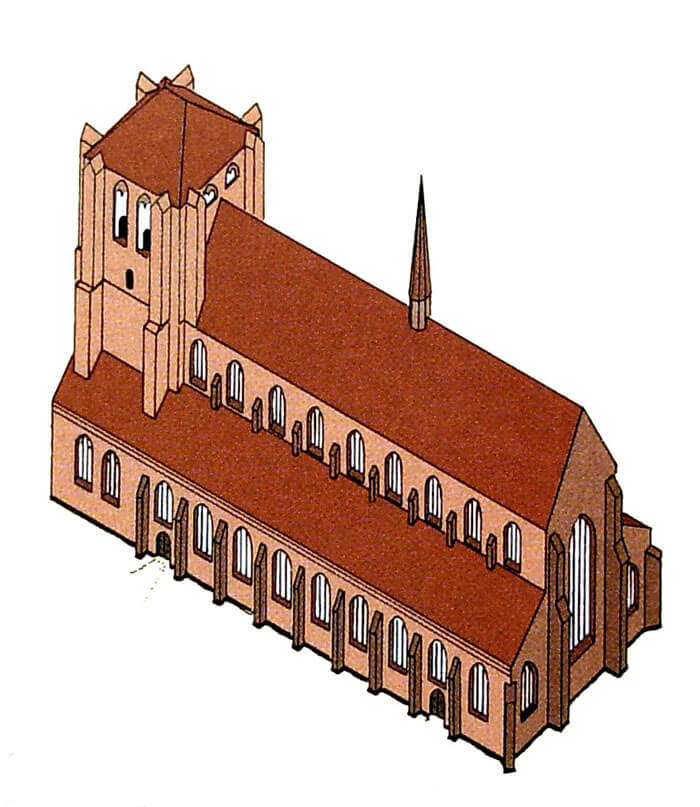

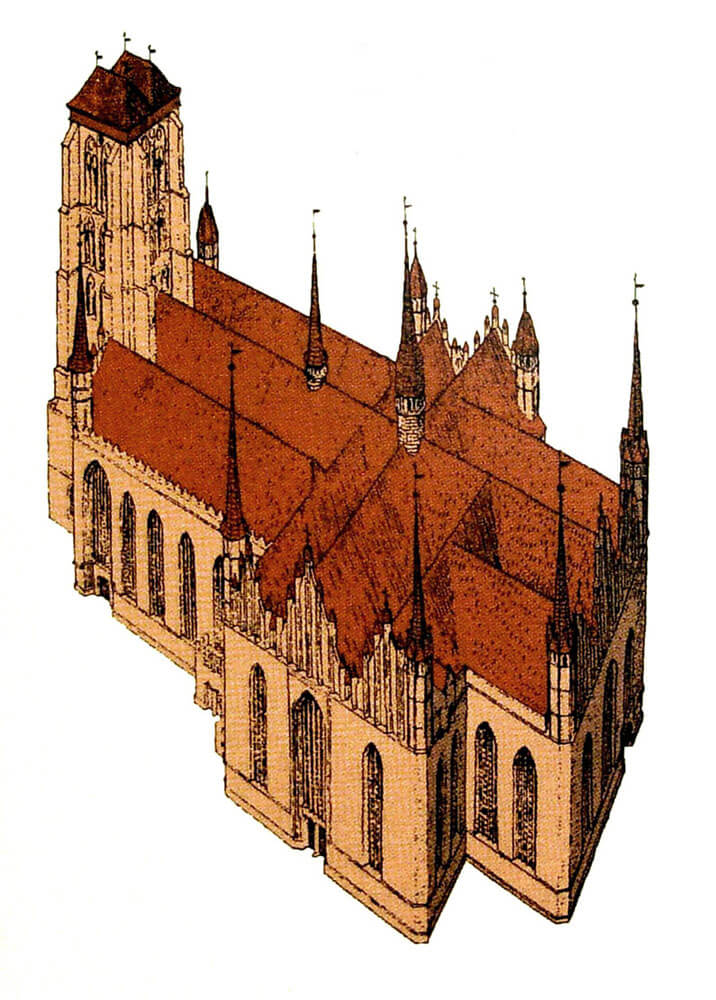

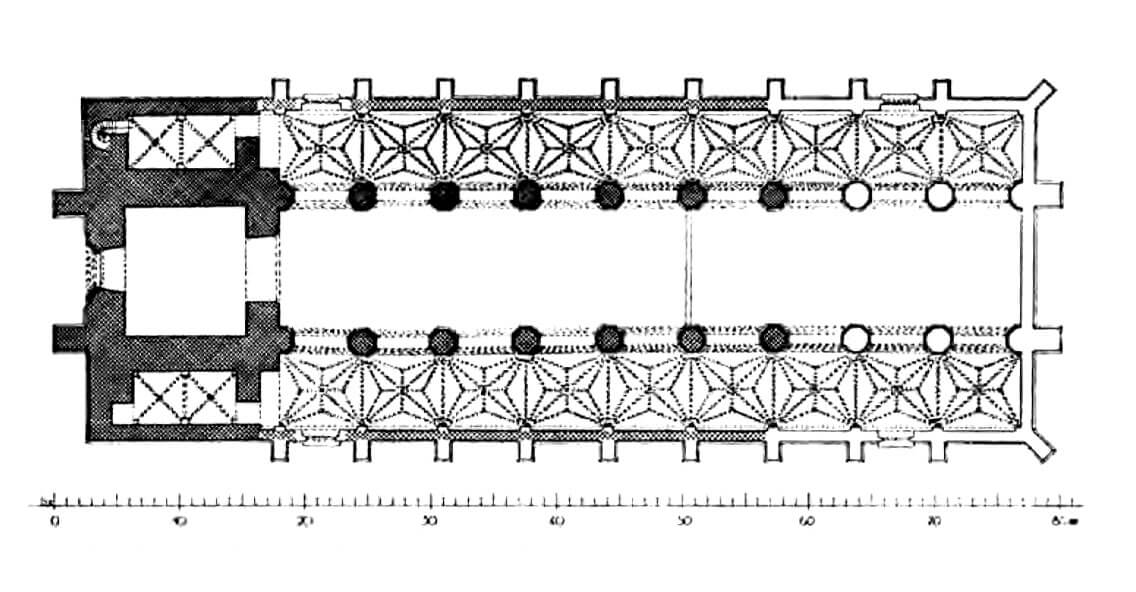

The Gothic St. Mary’s church from 1343-1370 was a three-aisle, nine-bay basilica with a very high central nave and a straight closure on the eastern side. It did not have a chancel distinguished externally, nor a transept. From the west there was a four-sided tower about 45 meters high, flanked from the north and south by two two-bay chapels of St. Rajnold and All Saints. In the medieval architecture of the Teutonic Order, such a form of the basilica was rare, probably the model for its nave was the central part of the Cistercian church in Pelplin.

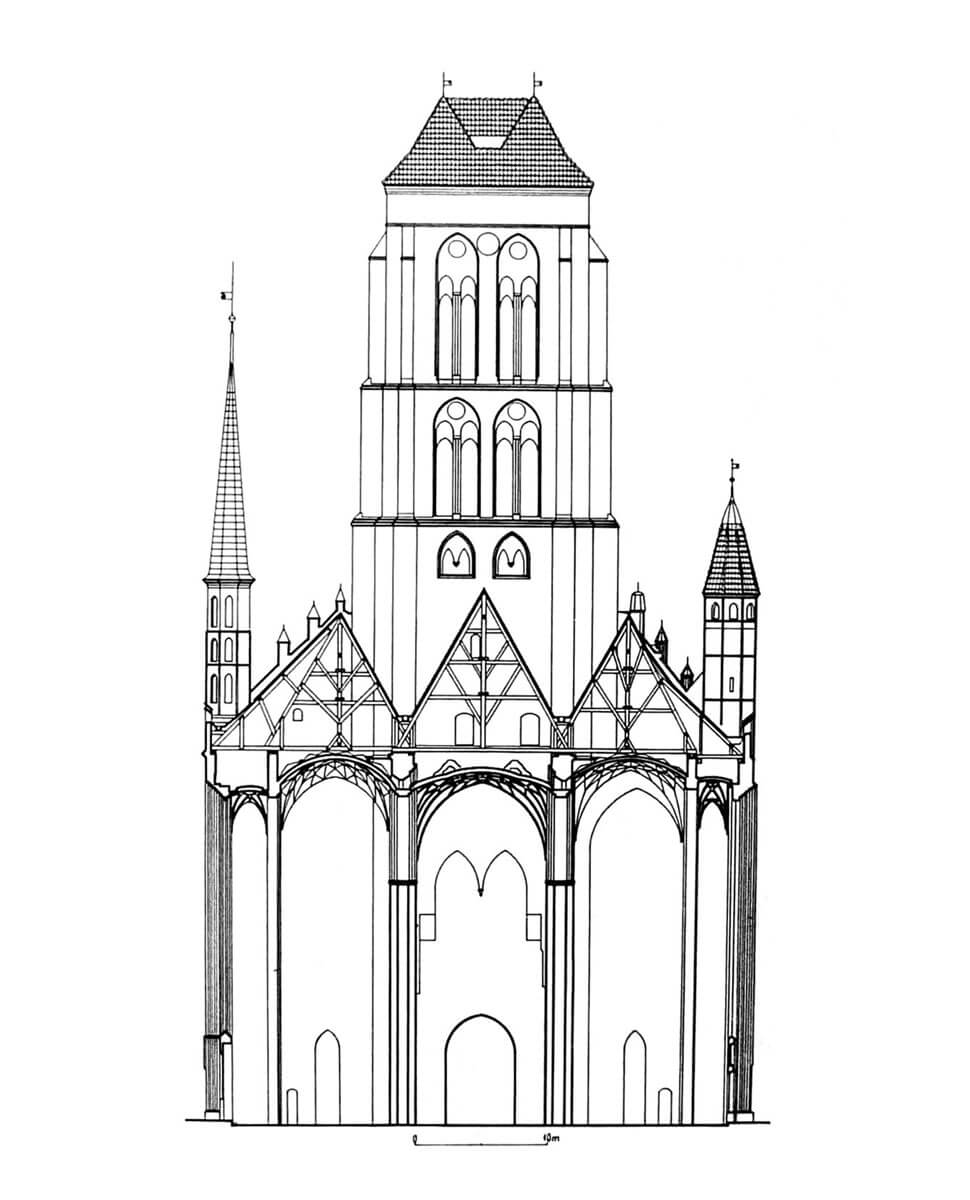

In the years 1379 – 1430, a magnificent new three-aisle, hall chancel and transept were built, which were so monumental that they badly corresponded with the much more modest older part of the church. This forced the tower to be raised by two additional storeys, to a height of just over 77 meters. The last stage was to adapt the nave to the size of the eastern part of the church. It was widened and received a hall form with three aisles equal in height with side chapels. To do this, fragments of walls between the pillars and the wall of the central nave were demolished, and in six bays parts of walls 5 meters wide and 15 meters high were made.

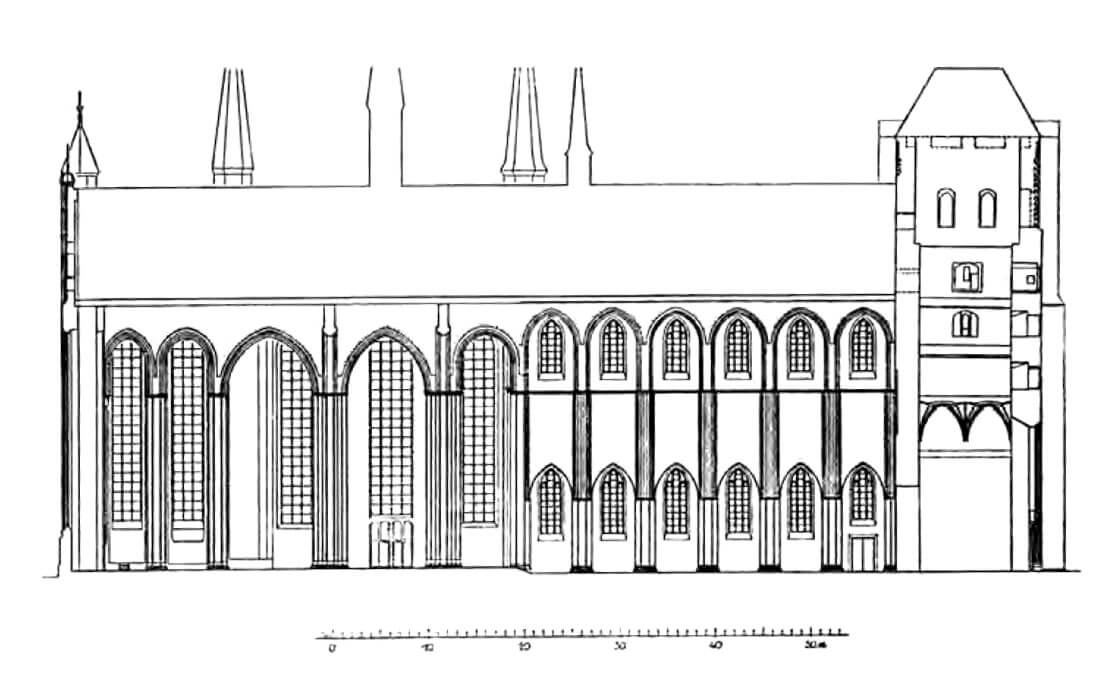

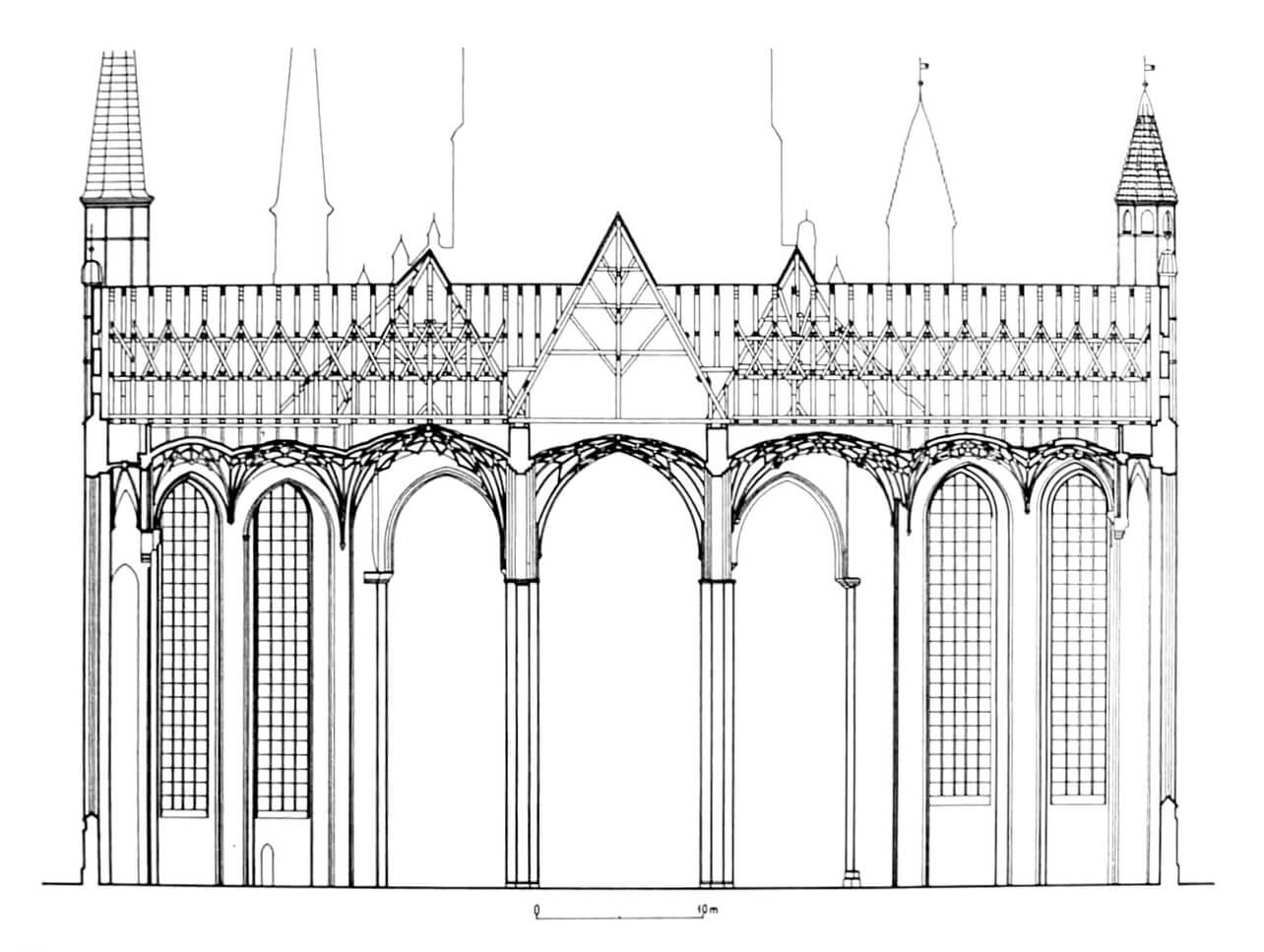

At the end of the Middle Ages, the church was finally shaped on the plan of an irregular Latin cross, 105.5 meters long and 66 meters wide, the largest brick sacral building in Europe in the Middle Ages. It received a hall form with an extensive and rich spatial program, which consisted of a three-aisle nave and also a three-aisle chancel. The transept in the southern part was erected in a three-aisle form, while the northern arm was built as two-aisle (the irregularity of the northern arm of the transept resulted from the need to adapt to the existing urban development). Chapels were attached to the aisles in all parts of the church, the shorter walls of which were also given the function of buttresses. As a result, the external façades could be devoid of divisions and could impress with large, non-segmented surfaces on which large windows clearly stood out. From the west, the temple was closed by a tower with flanking chapels , 77.6 meters high, covered with two hip roofs. Each aisle of the church was covered with a separate gable roof.

The whole church was illuminated by 37 large, pointed windows, which were usually filled with white glass to brighten up the interior. Colored representations of saints or coats of arms made up only a small part of the window surfaces. As the walls of the nave built at the end of the 15th century, in the east came into contact with the windows of the older part of the transept, during the construction of which narrower aisles were taken into account, after their expansion the builders had to solve the problem of connecting both parts. In the north of the church, the wall of the aisle was bent towards the interior, while in the south, the wall of the aisle met exactly in the center of the transverse aisle window, creating a window surface fault of 90 degrees.

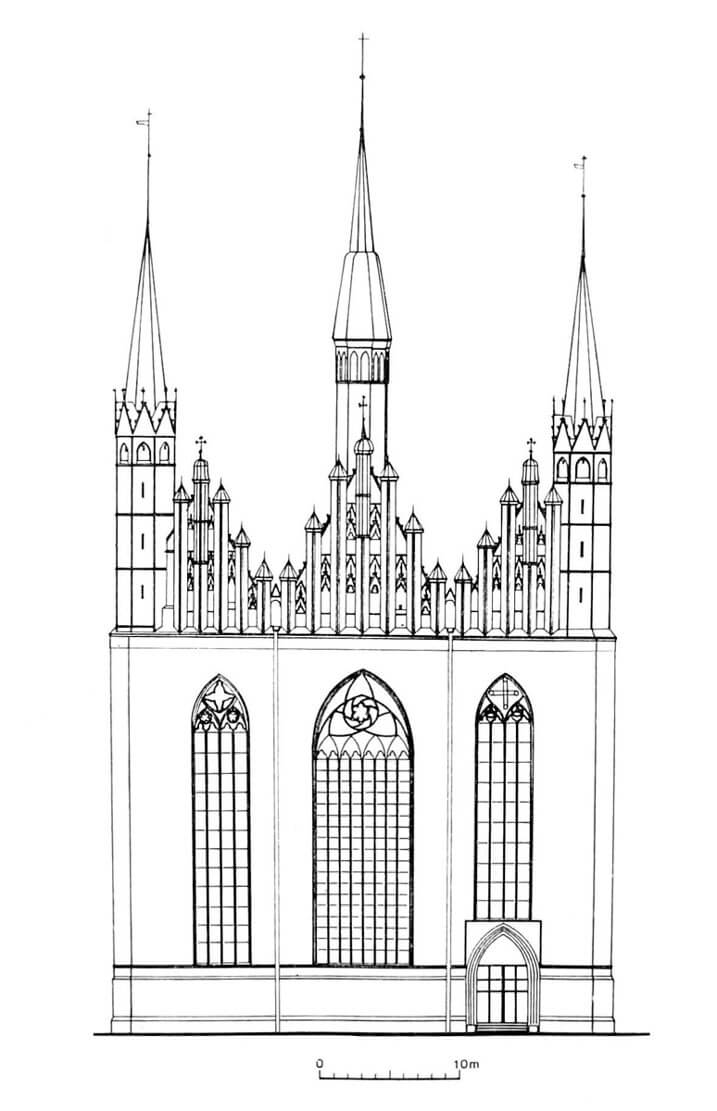

There were seven entrances to the interior of the church, each from a different street in the city. The portals were distinguished from the other brick parts of the church by the use of Gotland sandstone. Most of them were crowned with late Gothic ogee arches and richly moulded. The external façades of the main tower and the nave were left smooth and without decorations, only the wall at the tower was divided with high buttresses. The upper parts of the church were more important, as they were better visible above the town houses. Therefore, from the east, the chancel was closed with three Gothic gables, three more were crowned the southern arm of the transept, and two the northern one. Each of them consisted of moulded pillars, between which small windows with gables were pierced, used to illuminate the roof truss. The building was also decorated with eight polygonal corner turrets topped with spiers, one turret at the crossing and one turret on the ridge of the central nave. The upper parts of the chapels flanking the tower, were decorated with a row of blind windows and decorative battlement. The upper parts of the side aisles of the nave and the western walls of the transept were also decorated with single and grouped in pairs blendes, where they formed a series of small gables.

The west tower was divided into eight floors, with side chapels up to the third level. In the ground floor of the west wall, the main portal was embedded, higher a four-light window was framed by an openwork made of brick fittings, suspended slightly above the base of the portal arch. Above the frame there was a relief segmental arch, above three small windows with segmental heads. The three upper storeys of the tower were separated by an offset cornice. In the first of them, on the three free sides, there were two moulded, ogival blendes, divided into consecutive double-arched blendes with bell openings (on the eastern side, a similar motif was used, but without openings for which there was not enough space). In the middle and top storeys, in all elevations, there were a pair of openings with circular blendes in the arches.

The interior of the church was shaped by the uniform height of individual aisles, in which 28 huge, octagonal pillars were tasked with supporting the vaults at a height of 27 meters: net vaults in the nave and net transept, stellar vaults in the presbytery and some chapels, and diamond vaults in side aisles. The monumental layout gave the impression of a “forest” of pillars, especially impressive when looking diagonally from the arms of the transept. In addition, the impression of monumentality was intensified by the chapels located next to almost all walls of the church and having the same height as the aisles (at the end of the Middle Ages, there were over 30 chapels in the church and numerous individual altars located at the pillars of the nave). Most of the rib stellar vaults received a fragmented and dense figuration, which blurred the star layout (for this reason, these vaults are sometimes called stellar-net). Late Gothic diamond vaults, on the other hand, consisted not of ribs, but narrow “blades”, between which, as it were honeycombed, crystals emerged. Two bays of the four-arm stellar vault were placed in the tower porch from around 1360, which once also housed the chapel of St. Olaf.

In the Middle Ages, the interior of the church was not uniformly white, but on the contrary, it was characterized by many colors. Pillars and walls were decorated with geometric paintings, often figural or presenting whole views. In the presbytery, the moulded edges of the pillars were emphasized with vivid colors: green, blue, red. The pillars were also decorated with bossage popular in the Middle Ages, i.e. with painted patterns imitating stones or bricks. The chapels were especially richly decorated, in which whole cycles of paintings were often shown.

Current state

St. Mary’s church, often called the “Crown of Gdańsk”, is considered the largest temple in Europe built in the Middle Ages of bricks, inside which supposedly can be accommodate about 20,000 people. It is also situated among the most splendid parish churches of the Hanseatic towns, expressing bourgeois pride and emphasizing the strength of the local government. However, it surpasses them by a complex of vaults based in part on solutions typical of the Teutonic Knights state, and in part aristocratic solutions straight from Meissen.

Despite the turbulent history and numerous military operations conducted since its foundation, it managed to maintain its historical, Gothic form. Contemporary changes are limited to the lack of a turret on the ridge of the nave or the high granite platform erected in the chancel, the size and massiveness of which destroy the original spatial uniformity of the building. A large part of the original tracery in windows was also replaced in the 19th century and the gables, part of the vaults and all wooden elements were destroyed during World War II, and therefore had to be reconstructed after 1948. During the Reformation, the interior lost its original decor, due to the whitewashing of all facades and vaults with the loss of medieval polychromes.

Currently, church performs sacral functions, but is open to visitors throughout the year, from Monday to Saturday: from October to the end of April from 8.30 – 17.00, from May to the end of September from 8.30 – 18.30. In addition, the viewpoint is open on 24 March to the end of November on the tower.

Inside you will find many medieval monuments. The most valuable are: the stone Pieta from around 1410, a copy of the Last Judgment painted by Hans Memling in 1472, a sacramentary from 1482, an astronomical clock made in 1464-1470 by Hans Düringer and the main altar built in 1510-1517. During the restoration works, numerous late Gothic wall paintings were discovered that covered the entire church until the 16th century. Currently, significant fragments of the paintings have survived in the chapels of St. James, St. George and St. Jadwiga. Particularly interesting is the polychrome on the wall of the chapel of St. George, showing the view of the city with densely piled houses and fortifications with towers, a gate and a drawbridge over the moat.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Friedrich J., Gdańskie zabytki architektury do końca XVIII wieku, Gdańsk 1997.

Herrmann C., Kościół Mariacki w Gdańsku, Olsztyn 2007.

Walczak M., Kościoły gotyckie w Polsce, Kraków 2015.