History

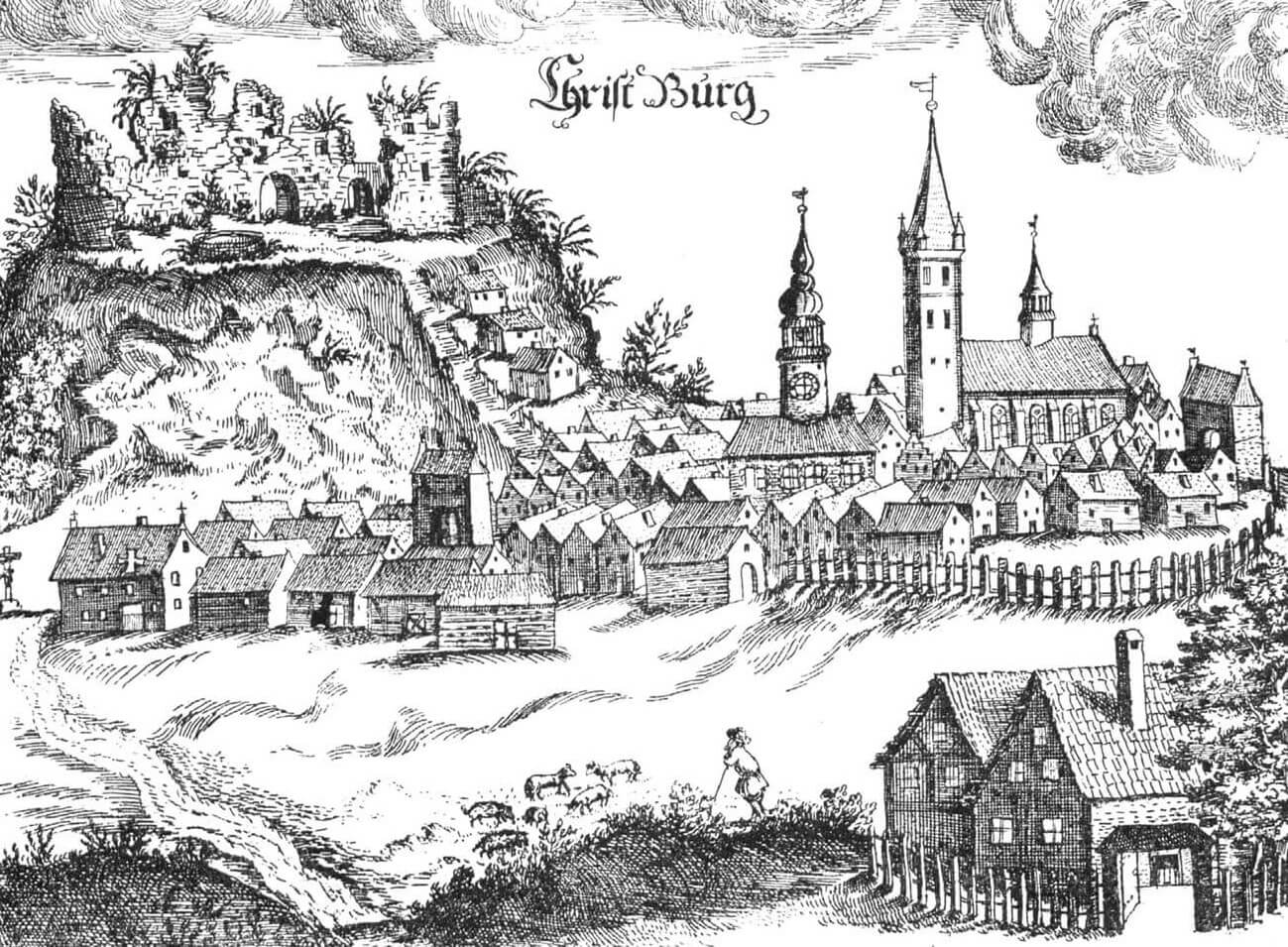

Dzierzgoń (German: Christburg) was first recorded in 1239, when the name Kirsberg was used, referring to the Stary Dzierzgoń (Alt Christburg). According to the chronicler Peter of Dusburg, this name referred to Christmas Day when the Teutonic Knights captured the Prussian stronghold, on which place they later established their own seat. It was captured twice by the Prussians, which probably influenced the decision to move the Teutonic seat from Stary Dzierzgoń to Dzierzgoń in 1247. The already brick castle was built in a new place very quickly, because around 1250 a commandry was established there. Moreover, in the years 1249-1250, the Peace of Dzierzgoń was concluded between the order and the Prussian tribes, ordering, among other things, the rebuilding of several destroyed churches by the Prussians, including the one in the settlement under the castle. On this occasion the first commander of Dzierzgoń was recorded, Heinrich Stange, who had a seal with the image of a battlemented tower.

During the great Second Prussian Uprising, which broke out in 1260 and lasted until 1274, the Dzierzgoń castle played a key strategic role. It was not captured, but it probably suffered some damages, which were repaired in the fourth quarter of the 13th century. From 1314, the castle was home to an Obersttrappier, a Teutonic dignitary responsible for equipping the Order with clothing. This meant that in the fourteenth century, the Dzierzgoń Castle was regarded as the largest armory alongside Malbork and the second food warehouse, after Brodnica Castle. In its fourteen farms large quantities of cattle were raised, especially horses, of which there were more than a thousand. The castle was also a strategically important point, the center of power in the densely populated Pomezania and the starting point for further conquests. The nearby Dzierzgoń river, which led the water route to the Vistula Lagoon and Baltic, was of significant importance.

In 1410, Albrecht von Schwarzburg, the Obersttrappier and Great Commander of Dzierzgoń, died in the Battle of Grunwald, and the castle was captured without a fight by King Jagiełło’s troops heading towards Malbork. The chronicler Jan Długosz, who described this event, emphasized the richness of the castle pantries and the Obersttrappier’s chamber, full of beautiful and expensive fabrics. The king supposedly liked the castle chapel, from which he ordered timber sculptures to be transported to the Kingdom of Poland. A garrison was left at the castle under the command of Zbigniew from Brzezie, but after the unsuccessful siege of Malbork, the Teutonic Knights began to recapture the lost castles. Leaving Dzierzgoń, after taking as much as possible, the army set fire to the castle, which then returned to the hands of the order.

In 1414, the castle in Dzierzgoń (“castrum Dzirgon”) burned down again after it was captured by the Polish army during the so-called Hunger War. Due to major damage and perhaps the problem of the fell of steep slope on which the fortress was built, it was decided in 1437 to transfer the commandry from Dzierzgoń to nearby Przezmark. Despite this, the castle was still used, and three years before moving, it was quite well stocked. At that time, among others, 129 crossbows, 73 handguns, 12,000 belts and half a dozen spears were recorded in warehouses. In addition, protective equipment, 42 shields, barrels with nails, horseshoes, iron bars, girths, traveling beds, ropes, and Hungarian leathers were kept in the armory. The artillery consisted of 15 bombards for stone and metal balls with a supply of 11 gunpowder and two saltpeter barrels.

At the beginning of the Polish-Teutonic Thirteen Years’ War, in February 1454, the stronghold was burned at the hands of the rebellious burghers from the anti-Teutonic Prussian Union. However, no total destruction was carried out, because in June the same year the mercenary army in exchange for unpaid pay demanded, among others, the Dzierzgoń castle. A few months later, in September, the Teutonic Knights captured it again and kept until the end of the war, which ended in 1466 with the signing of the Second Peace of Toruń. Under it, Dzierzgoń was taken over by the Polish kingdom, and the seat of the starosty and the town court were located in the preserved chambers of the castle. In 1520, during the last Polish-Teutonic war, there were direct clashes between the crews of the former Dzierzgoń commandry castles. The Teutonic forces from Przezmark came to Dzierzgoń, burned the farm, suburbs, barns, and then the town. The castle has survived, but its weak garrison was unable to protect the townspeople.

In the 17th century there were still offices in the castle, but the building fell into decline, especially in the second half of the century, after the Swedish wars. In 1647 and 1664, records were made of the poor condition of the castle chapel and the even worse condition of the remaining walls. In 1689, one of the wings was renovated for the needs of the town court, but these were the only construction investments. Some of the buildings were demolished at the beginning of the 18th century in order to obtain material for the construction of the nearby Reformed monastery and the associated forge. At the end of the 18th century, the Prussian authorities decided to permanently abandon the castle, which was completely demolished during the 19th century and its areas were turned into a park.

Architecture

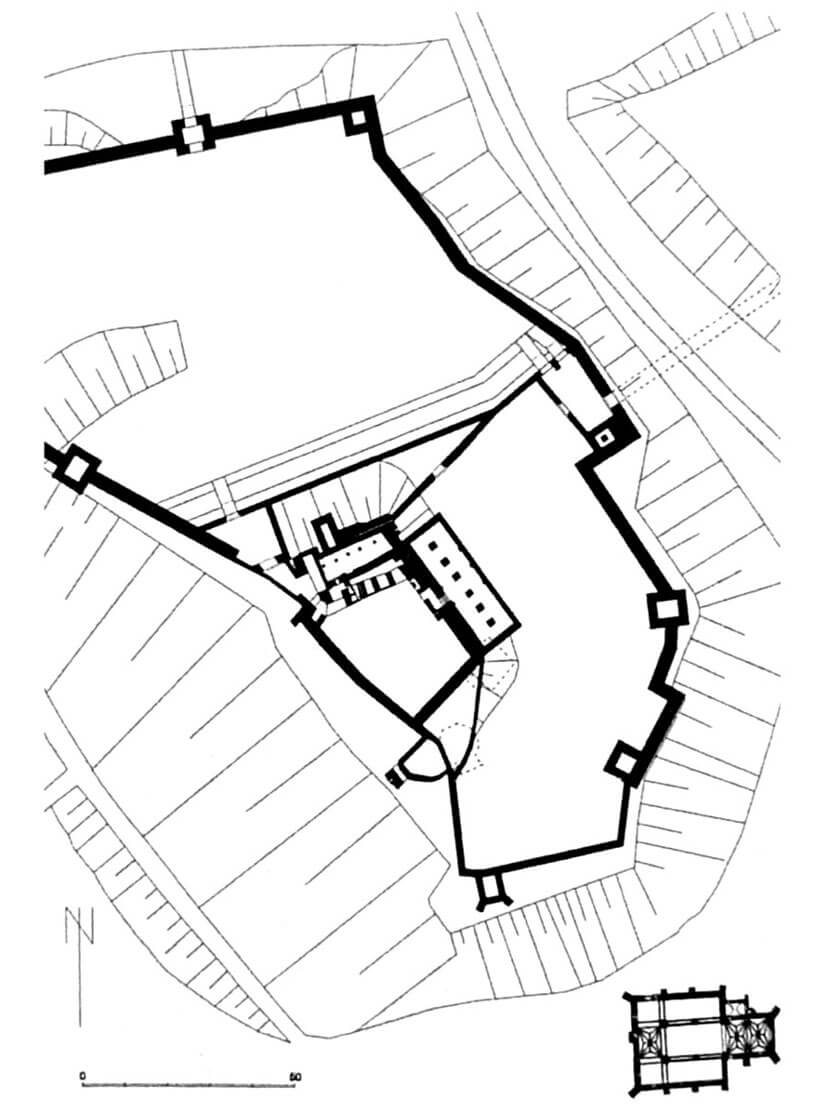

The castle was built on top of a hill with very good defense conditions. Access to the peak, flattened during construction, was defended from the north, east and south by steep and 30-meter high slopes. In addition, on the southern side at the foot of the hill the Dzierzgoń River flowed rapidly, originally washing its slopes (which in the future became the cause of landslides and probably construction disasters). The more convenient approach was only from the west, from the narrowing side of the hill, which was cut by the ditch at the narrowest point. An unfavorable element for defensive values could be a slightly lower hill called St. Anna, located on the north-east side and separated from the castle by a ravine. At the foot of both hills, on the east and partly south side, along the riverbed extended the buildings of a medieval settlement, changed in 1288 to the town. Its defense was made of earth ramparts with a wooden palisade and brick gatehouses.

The castle consisted of three separate parts: the commandry ward, located at the highest point of the area, and the northern and eastern outer baileys, connected by a defensive wall, probably reinforced with four four-sided towers, spaced about 35 meters from each other. The defensive wall, up to 3.2 meters wide in its thickest places, was probably topped with a battlement and a wall-walk for the defenders. The entire castle was irregular, adapted to the form of the terrain, built of bricks laid in a monk bond, on a foundation of granite stones. It did not yet have the form of a regular Teutonic commandry castle, with three or four wings closing the inner courtyard.

The upper ward had at least two rectangular wings, placed perpendicular to each other, without a zwinger and a surrounding moat. The trapezoid-shaped northern wing was shorter, about 15-16 meters long and 4.7 to 5.3 meters wide, while the eastern wing was over 40 meters long and about 12 meters wide. Both had basements. From the courtyard side, brick, probably two-story cloisters were added to both parts, providing communication between floors and rooms. Representative chambers, such as the refectory or chapel, were probably located on the first floor of a larger building. Medieval inventories also recorded warehouses, an armory, stores of robes, cloth and linen, pantries, and the cellars of the commander and the knights. It were probably located in the upper ward, although certainly not on the representative and residential first floor. On the ground floor of one of the wings there must have been a kitchen of the Teutonic Knights and a kitchen where meals were prepared for the commander’s table. There were probably also servants’ quarters there. Basements traditionally served as warehouses and pantries.

At the northern, smaller wing of the castle, approximately halfway along its length, the main tower was built on the outside. It had several floors (with a basement), built on a quadrilateral plan, measuring 5.2 x 6.6 meters. It flanked the entrance to the courtyard, which was located in the gatehouse located next to it. In its vicinity, relics of further walls were discovered, indicating the existence of an extensive, long foregate. The courtyard was paved, in its southern part there was a well, and nearby there was an unusual, interesting building on a pentagonal plan, measuring 9 x 8.7 meters, connected by an arcade porch to a four-sided tower at the edge of the slope. Perhaps it was a bathhouse with a bridge to the latrine tower, as channels for water or waste were discovered there.

The larger outer bailey was located in the northern part of the hill, where the slope was gentler. The second outer bailey surrounded the commandry buildings from the east and partially from the south. There were brick, free-standing buildings without basements, but with stone and ceramic tile floors. It probably housed the economic buildings recorded in documents: a shoe workshop, a saddlery, a forge, a granary, as well as a brewery, a malt house and a bakery. On the opposite side, on the smaller hill of St. Anna, in the 13th century a monastic cemetery was established and a chapel was built. This place was probably connected to the castle by a wooden footbridge over the gorge. Outside the castle, there were also Teutonic Knights farms, mills and a garden.

Current state

The castle has not survived to this day. Only the fragments of the foundations and the pavement of the castle courtyard are left. During the excavation works, some architectural details were also unveiled in the form of sculptures, bosses, fragments of vault ribs and floor tiles. The area of the castle hill is accessible to visitors.

bibliography:

Garniec M., Garniec-Jackiewicz M., Zamki państwa krzyżackiego w dawnych Prusach, Olsztyn 2006.

Haftka M., Zamki krzyżackie. Dzierźgoń-Przezmark-Sztum, Gdańsk 2010.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Torbus T., Zamki konwentualne państwa krzyżackiego w Prusach, część II, katalog, Gdańsk 2023.