History

The Gothic castle in Cieszyn was built on a hill, which was originally the seat of the Gołęszyce tribe, and then a center with the rank of a castellany. The bull of Pope Hadrian IV from 1155 was the first written mention of the town, recorded under the name Tescin. In 1223, the Cieszyn castellany (“castellatura de Tessin”) was recorded along with the castle church of St. Nicholas, while the Cieszyn castellan named Jan was recorded in a document from 1229. Subsequent records of the Cieszyn stronghold’s castellans were recorded in 1258 and 1283. In the 13th century, a town developed from a small settlement near the stronghold, recorded in 1284 as “civitas Tessin”.

In the 1170s, the Cieszyn castellany became part of the Racibórz principality of Mieszko Tanglefoot, assigned to him by Bolesław the Tall after the revolts of the junior princes and imperial intervention. At that time, a stone rotunda dedicated to St. Nicholas was built in the hillfort. From the early years of the 13th century, Cieszyn was within the Piast dominion of Opole and Racibórz, after Mieszko Tanglefoot, managed by Kazimierz I and Mieszko II the Obese. During the latter’s rule, in a document issued between 1238 and 1246, the term castle (“castra Tessin”) was used for the first time in relation to Cieszyn, although most likely it was not yet a stone defensive building, but only a late phase of a wooden and earth hillfort. The Cieszyn castle was also recorded in a document of Pope Innocent IV from 1245 and in the lifetime grant of Cieszyn and Racibórz by Mieszko II to his mother, a year later.

The reconstruction of the wood and earth stronghold into a stone castle could have been initiated by the first Cieszyn prince Mieszko, who from around 1281-1282 ruled together with his brother Przemysław in Cieszyn, Oświęcim and Racibórz, and from 1290 independently in Cieszyn and Oświęcim. The rebuilding was continued in the 14th century by his successors: son Kazimierz I and grandson Przemysław I Noszak. In the 15th century, the castle fortifications were probably adapted to the use of increasingly stronger firearms, especially after the experiences of the Hussite Wars. The housing standard had to be raised in line with the late medieval requirements of the ruling class, as well as the residential space enlarged, especially since in the 15th century Cieszyn was periodically co-ruled by various members of the dynasty of Silesian Piasts.

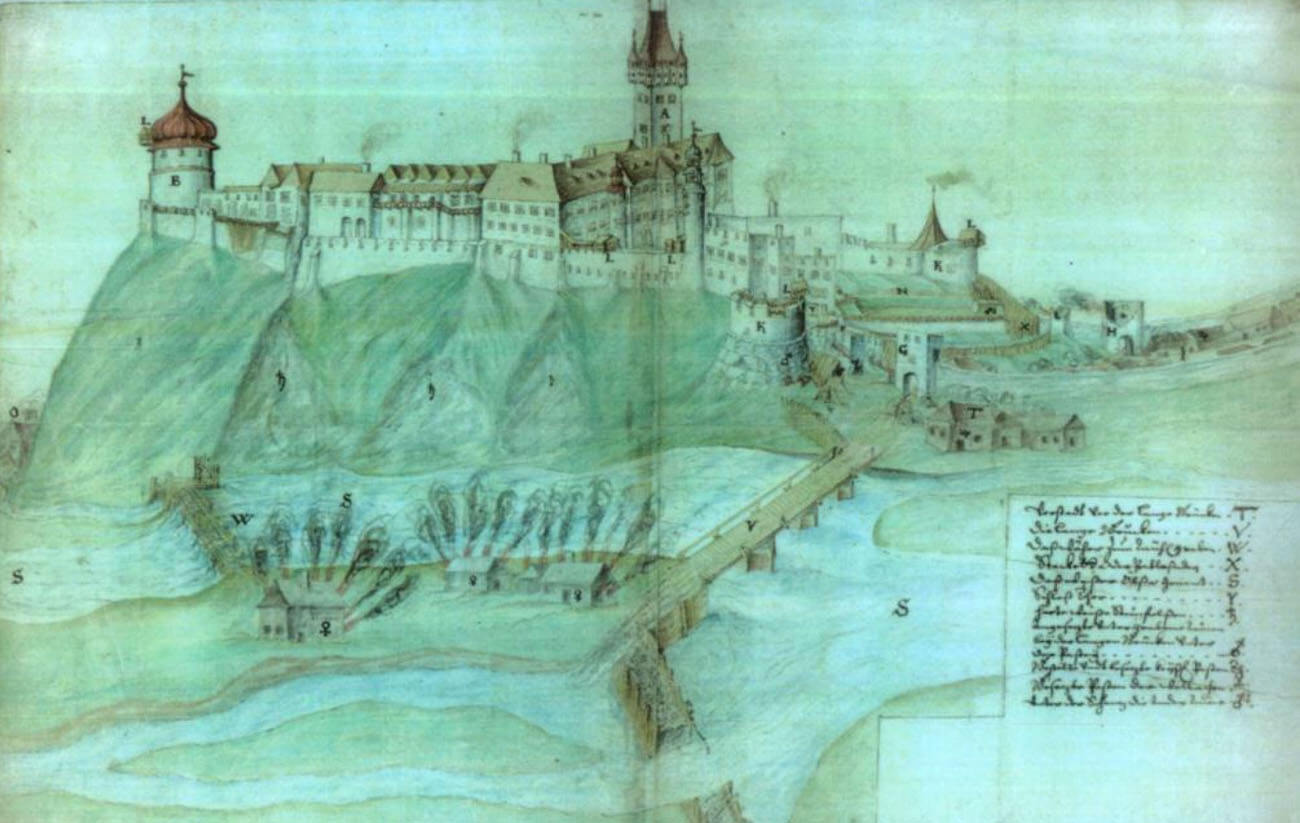

In 1552, during the rule of Prince Wenceslaus III Adam, a great fire devastated the town and the castle. Presumably, as part of the reconstruction, the castle was transformed in the Renaissance style, for which the prince could have obtained income from the sale of the Skoczów and Strumień estates in 1573. His successor was Duchess Sidonia Catherine, during which the economy of the principality was rebuilt, ruined by the extravagance of Wenceslaus III. Further work on the castle could have been carried out by the son of Wenceslaus III and Sidonia, Adam Wenceslaus, especially after the fire of 1603. Until his death in 1617, the prince probably initiated the reconstruction of the castle in the late Renaissance style.

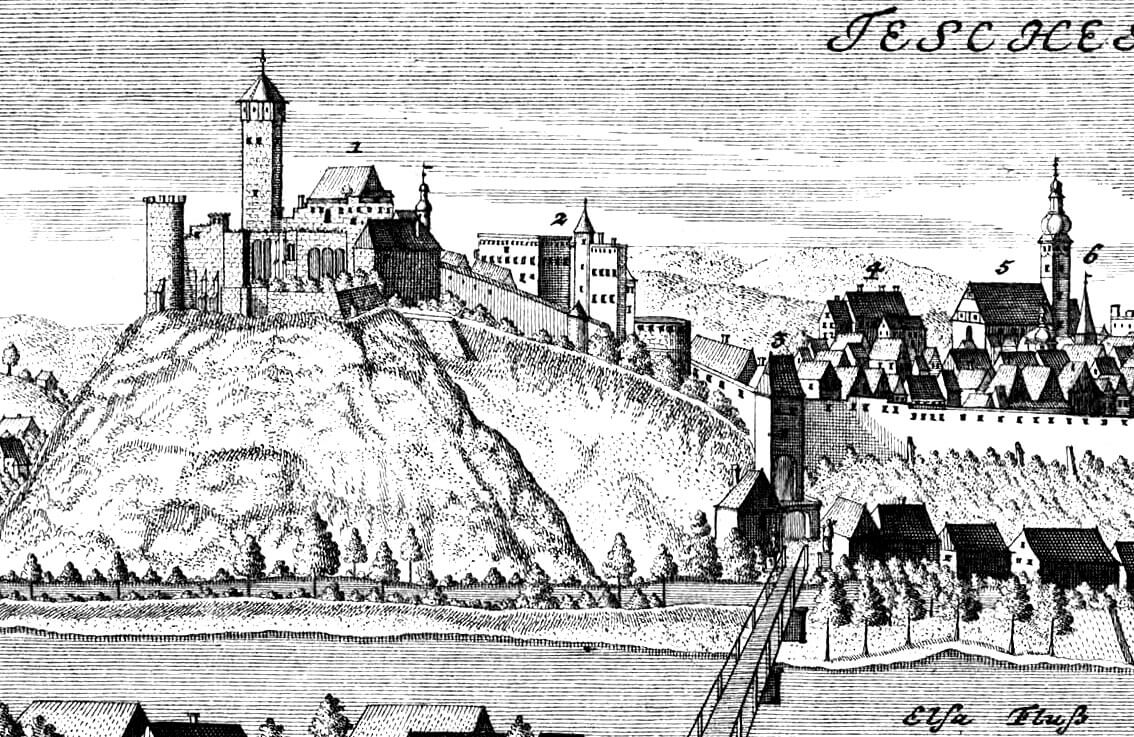

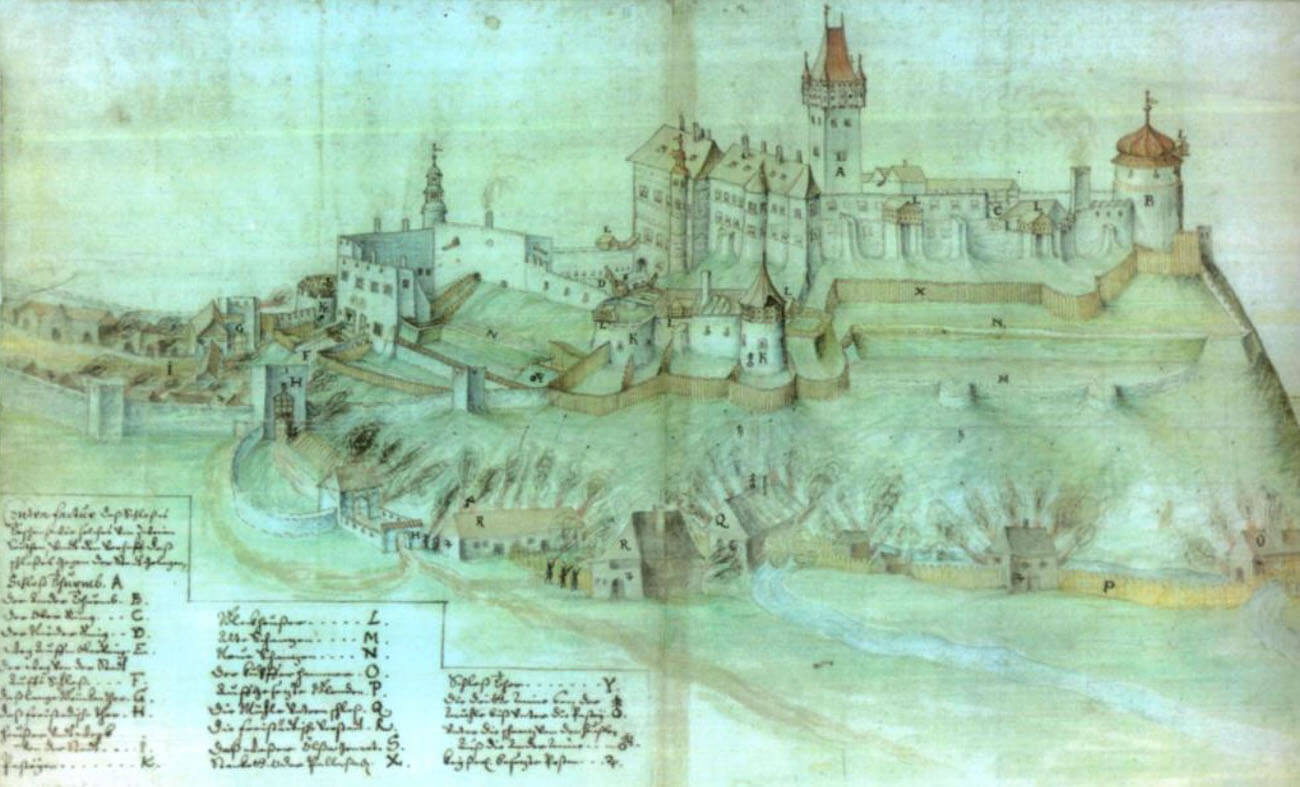

The castle served as the center of power until the Thirty Years’ War and the extinction of the Cieszyn Piasts line, of which the last male representative, Frederick William, died in 1625. After him daughter of Prince Adam Wenceslaus of Cieszyn, Elisabeth Lucrezia took over power, but the castle was destroyed by Swedish troops in 1645. The devastated principality was unable to finance the reconstruction, which caused the castle buildings to increasingly decline. When Princess Elisabeth died in 1653, pursuant to previous agreements, Cieszyn was incorporated into the Czech domain of the Habsburgs. Over time, the abandoned castle was dismantled in order to obtain building materials. This process was slow, because the impressive shape of the medieval buildings was still depicted in the 18th-century vedutes, but by the first half of the 19th century, most of the fortifications and residential buildings had been slighted.

Architecture

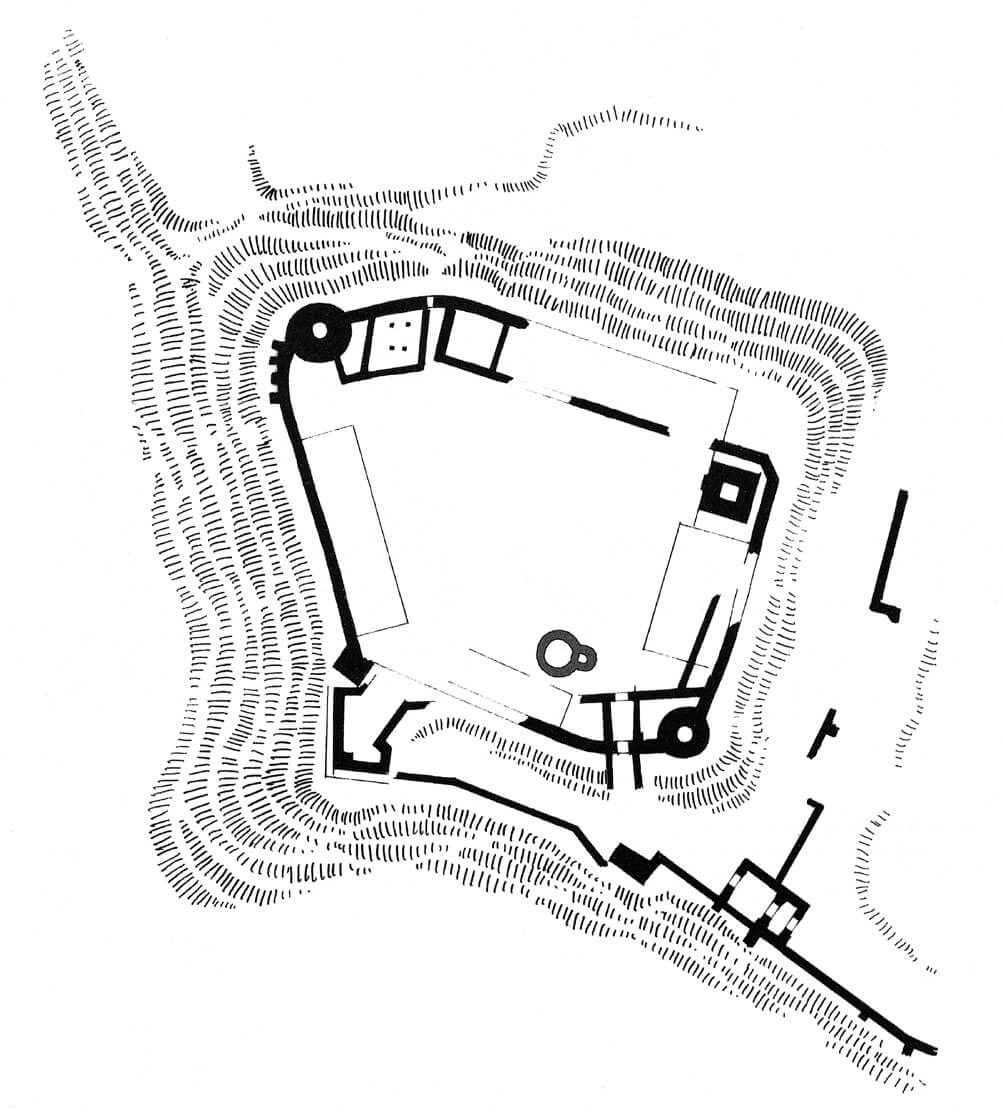

The castle was built on a relatively high hill (300 meters above sea level) on the northern side of the Olza River. The slopes descending towards it were steep, as were the western and northern slopes, the latter towering over the valley of the Bobrówka stream. A slightly gentler approach led from the east, where the gradually decreasing ground was designated for the outer bailey, and finally reached the terrace on which the settlement and later the fortified town of Cieszyn developed. The town was protected by the Mill canal from the south, and further by the Olza river, the Bobrówka stream from the north and the moat from the east.

The Gothic castle was divided into upper and lower wards. The lower one housed utility rooms and houses for the servants. It probably had mostly or even entirely buildings and fortifications made od wood throughout most of the Middle Ages. The wall on the side of the upper ward and the walls connecting the town fortifications, as well as the towers and bastions visible on the vedutas, could only have been built during the period of the development of firearms, in the 15th or 16th century. Situated on the south-eastern side, the town probably did not have its own fortifications on the side of the castle. In other directions, it was surrounded by a wall only from the end of the 15th century, creating a pear-shaped form, gradually expanding towards the south-east. The entrance to it was through the Upper Gate from the east, the Fryštát (Lower) Gate from the north and the Water Gate from the south.

The upper ward had an irregular shape adapted to the terrain of the hill and the older hillfort. The defense was based on the line of a stone wall about 1.9 meters thick, running along the edge of the slopes. On the outside, the curtains were reinforced with buttresses on the steepest slopes. In the late Middle Ages, wooden or half-timbered porches, known from vedutas, could have been built on them, playing defensive, communication or latrine function. In the north-eastern corner there was a four-sided tower (so-called Piast’s Tower), not directly connected to the wall curtains, but located close to it. It was built of erratic stone, also ashlar was used to strengthen the corners and to frame the openings. The top floor was made of bricks in the Flemish bond after 1520. The entrance to the upper ward was located in the south-east corner, in a four-sided gatehouse. The gate was protected by a cylindrical tower with a diameter of almost 10 meters and massive walls 3.3 meters thick. An even more massive cylindrical tower was located in the north-west corner. Its external diameter was about 12 meters, the thickness of the walls on the ground floor was about 4.2 meters. Both cylindrical towers could have been late medieval works, adapted for the use of firearms.

In the upper part of the Cieszyn castle, the buildings consisted of living quarters, with the prince’s representative chambers and the direct economic facilities associated with them (e.g. kitchen, stables). Residential buildings were attached to the inner facade of the defensive wall. The oldest ones were probably located near the wall in the northern part of the courtyard, traditionally opposite the entrance gate to the castle. Unusually, in the safest place on the western side, furthest from the gentle eastern slopes, there were probably no buildings. In the 16th century a kitchen was built in the north-west corner, and there were also north, south and east wings.

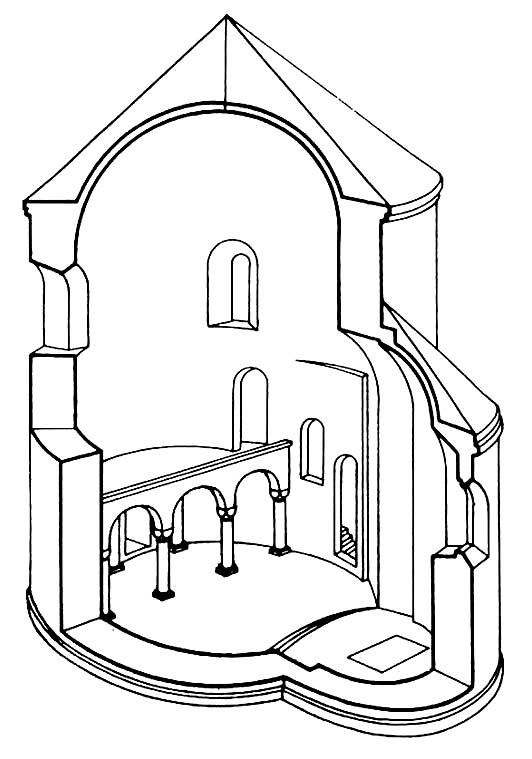

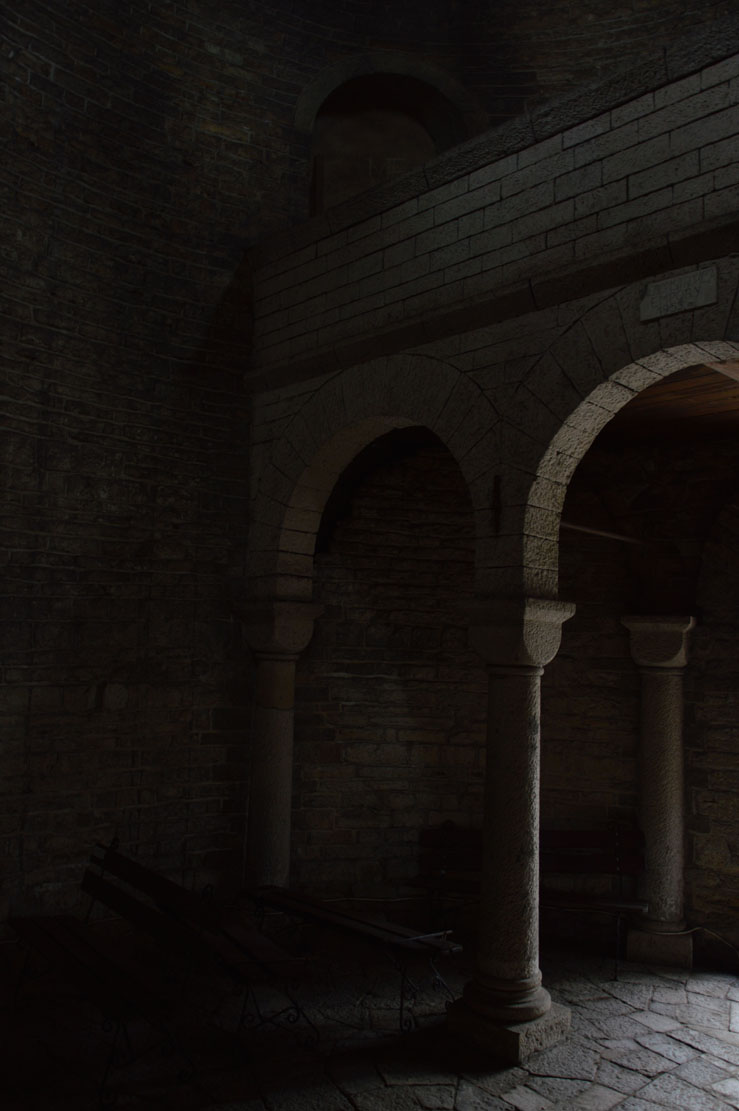

In the southern part of the courtyard there was a Romanesque rotunda of St. Nicholas, serving as a castle church. It was built of flat limestones in the opus emplectum technique, with a filling in the form of crushed stone bound with lime mortar. It was created on a circular plan with a diameter of 6.3 meters, with a horseshoe-shaped apse with a diameter of 2.8 meters on the eastern side. The height of the nave to the crown of the walls was about 13 meters, while the apse was 6.8 meters. The rotunda was originally illuminated by small, splayed on both sides Romanesque windows with semicircular heads, as well as slit openings at the staircase. In the 14th century, some of the windows were widened. The entrance portal, semicircular with a smooth tympanum slab, was placed on the western side of the nave.

Inside the rotunda, the nave was vaulted with a dome made of flat, concentrically arranged stone tiles, and the apse was topped with a conch. In the northern, specially thickened part of the nave, a single-flight 0.6-meter-wide staircase was placed in the thickness of the wall, leading to the gallery, as well as to the Romanesque portal located at the top of the stairs, which was the passage to the palatium. The gallery, a kind of balcony supported by two columns and four half-columns, was originally covered with two incomplete bays of a groin vault. The apse was connected to the nave by a step creating a kind of rood arch.

Current state

Until today, from the original Cieszyn castle survived the so-called Piast Tower, the Romanesque rotunda, the remains of the ground floor of the gatehouse, relics of the 16th century kitchen and the lower part of the corner, round tower. Rotunda of St. Nicholas is one of the oldest and most valuable monuments of Polish sacral buildings, with the original perimeter walls preserved almost completely. It presents a very high level both in terms of construction technique and spatial program, but the present appearance of its gallery is the result of post-war reconstruction. The castle is open to visitors every day during the winter from 9 to 16 and in the summer from 9 to 19.

bibliography:

Jagosz-Zarzycka Z., T., Rodzińska-Chorąży, Rotunda na Górze Zamkowej w Cieszynie – prace badawcze w 2013 roku [w:] Średniowieczna sakralna architektura w Polsce w świetle najnowszych badań. Materiały z sesji naukowej zorganizowanej przez Muzeum Początków Państwa Polskiego w Gnieźnie 13-15 listopada 2013 roku, Gniezno 2014.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Przybyłok A., Mury miejskie na Górnym Śląsku w późnym średniowieczu, Łódź 2014.

Siemko P., Zamki na Górnym Śląsku od ich powstania do końca wojny trzydziestoletniej, Katowice 2023.

Sztuka polska przedromańska i romańska do schyłku XIII wieku, red. M. Walicki, Warszawa 1971.

Świechowski Z., Architektura romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 2000.

Świechowski Z., Sztuka romańska w Polsce, Warszawa 1990.

Tomaszewski A., Romańskie kościoły z emporami zachodnimi na obszarze Polski, Czech i Węgier, Wrocław 1974.