History

The Pałuki area, characterized by a variety of soils, extensive and wet meadows, rich forests and dry clumps in river valleys and lakes, has enabled the existence and life of human communities with different lifestyles since the end of the Lower Paleolithic Period. Hunters and gatherers were the first to reach Biskupin around 10,000 – 8,000 BC. Their successors also lived here in the Middle Paleolithic. After a longer break in the years around 3500-2500 BC the first farmers appeared, also involved in breeding pigs and cattle, as well as gathering and hunting. These few groups of people, made up of large families or clans in which women played a significant role, settled in several places on the clumps at Lake Biskupińskie. They stayed in long houses and half-dugouts, leading semi-sedentary lives. They belonged to the Funnelbeaker culture, later also the Globular Amphora culture and Corded Ware culture. At the end of the Late Stone Age, around 1800 B.C. hunters and gatherers from the Comb Ceramic culture (named after the way of decorating the pottery) came to the vicinity of Biskupin, and in the early Bronze Age, in the years 1700-1600 BC there were groups of breeders, hunters and gatherers in the area, who left traces of camps and settlements, and a large square surrounded by a ditch, for closing large herds of cattle and pigs.

The settlement of the Biskupin area in the middle and late Bronze Age was quite rare (several burial places, lost tools, “sacrifices” sunk in swamps). Only in the early Iron Age, when there was a particularly intense development of the culture called Lusatian, which included tribes with difficult to determine ethnicity, nearby lands began to be intensively colonized. Individual families, which were initially dispersed, as a result of the increased development of productivity, especially breeding of domesticated animals and agriculture, reached such a degree of development that enabled them to introduce their tribal system to a higher level of organization, which enabled the joint effort of a great defensive settlement.

Based on dendrochronological studies of wooden elements, it was established that the Biskupin stronghold was probably founded in 738 BC and was used for the next 150 years in two phases. Its population was engaged in agriculture (wheat, barley, millet, peas, vetch, broad bean, turnip, flax, lentils, poppy), fishing, domestic animal breeding (pigs, small cattle, sheep, goats, small horses, dogs were also kept) and crafts. The second, slightly smaller, but also defensive settlement functioned longer, and its end was associated with a fire, perhaps caused by the Scythian invasion. The problem for which reconstruction was abandoned could have been the rise in the lake water level or repeated floods associated with the removal of large areas of forests.

In the 5th / 4th century BC another, this time open settlement, much smaller and poorer, was established in Biskupin, a number of settlements on the shores of the lake also functioned then. In the early Middle Ages, the settlement was already located on a peninsula formed from the former island, which was cut off from the land by a palisade. The final decline or relocation of this center was associated with the growing importance of the Piast dynasty in the 10th century and the entry of Biskupin into a grand-feudal estate, possibly belonging to the prince in the nearby Gniezno. In the eleventh century, the ruler gave the surrounding property to the archbishop of Gniezno, which was confirmed by the papal bull of 1136, naming one of the villages at the lake as Starzy Biskupici (22 settlers with families lived in it). In 1325 the village was moved by Gniezno archbishop to the area of today’s village of Biskupin.

Architecture

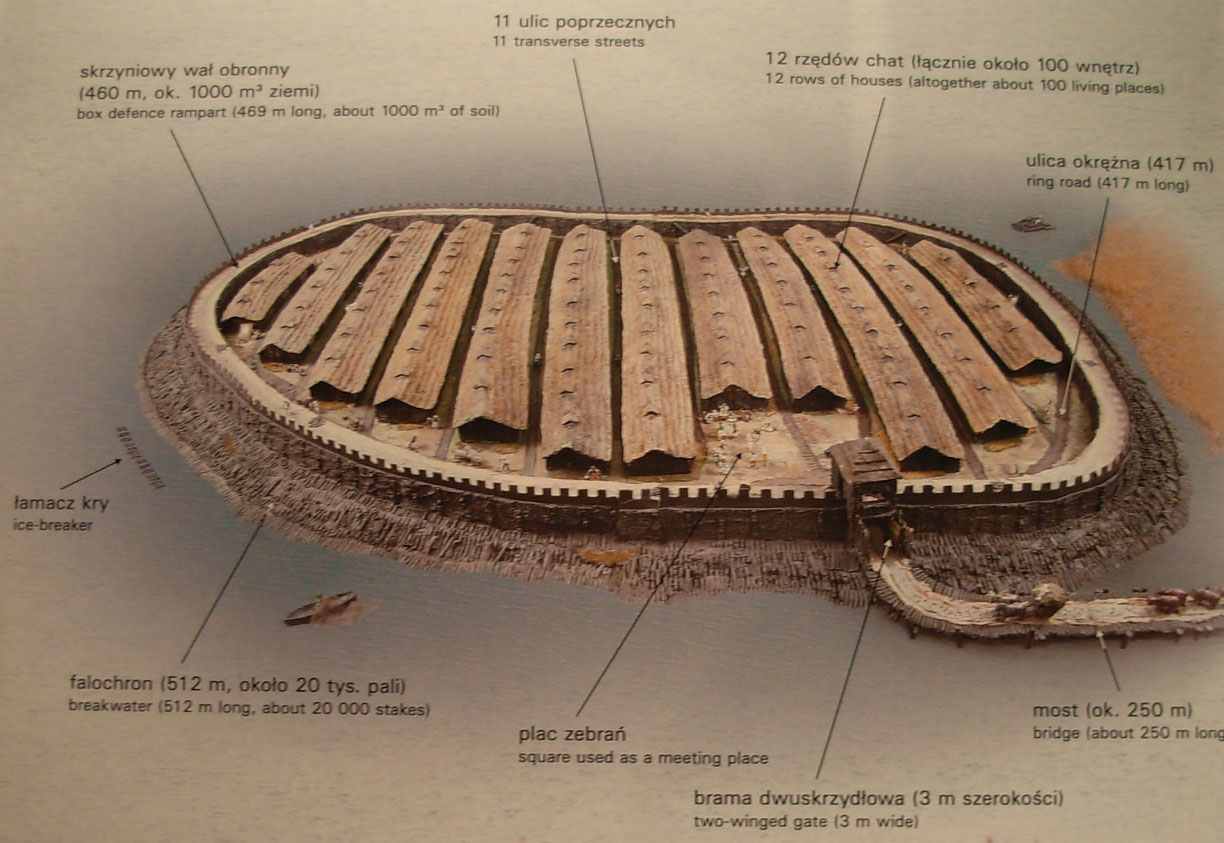

The defensive settlement was founded on the wet island of the Biskupińskie Lake, to which the Gąsawka River flowed from the south, originally fed by several surrounding streams. Nearby, there was also a source of crystalline water, valuable in swampy and muddy terrain. The island had an oval shape projecting about 1 meter above the water surface and an area of about 2 ha. The island was about 200 meters long and 160 meters wide. It was encircled with a 3 to 9 rows of oak and pine piles, driven right next to each other into the bottom of the lake, obliquely, at an angle of 45 °, over an area of 2 to 9 meters wide. The total number of these sharpened piles was over 35,000. They acted as a breakwater, protecting the island’s shores, including the rampart, against water and ice pressure, and also hindered potential attackers’ approach to fortifications. Because the north-west part of the settlement, due to winds, was most exposed to the pressure of ice floes, it was additionally secured with an area consisting of several hundred piles inclined towards the north-west.

The main part of the fortifications was located behind the breakwater, a timber – earth rampart 463 meters long, 3 meters wide and an alleged height of up to 6 meters. The rampart rested on oak logs arranged in quadrangles with sides of 3-3.5 meters. On them stood a wooden shaft scaffolding in the form of crates 1 meter wide, made of oak logs, tied together. From the inside of the shaft, in order to strengthen the structure, this binding was supported by oak columns. The crates were filled with earth and sand, and also covered with clay to protect the walls against fire. The rampart was crowned by the breastwork, protecting the defensive walk-wall behind it. It had the form of a wooden battlement or wall bristled with sharp piles. At the base of the rampart, which narrowed slightly upwards, piles of stones were accumulated every few steps, probably serving as missles during defense.

In the southwestern part of the perimeter, both the rampart and the breakwater were cut by a gate 3 meters wide. Along with the gate passage, it measured as much as 8 meters in length. From the outside it was put in the form of two rows of piles, designed to close down the attackers and allow them to attack the double-leaf gates only in small groups. The gates turned on the tenons placed in the lintel. Probably over the gate passage there was a defensive watchtower dominating over the settlement. Above the water area, a wooden, 120 meter long oak bridge led to it, directed towards the south-west shore of the lake.

Inside the settlement there were about 102-106 residential and economic houses, separating the streets and a small square. The building plan was based on rows of houses and a system of communication routes with a main passage 3 meters wide, which circled the settlement running parallel to the rampart. Eleven transverse streets departed from it, parallel to each other, almost the same width, located more or less on the east-west line. The direction of the streets and their slight bend testify that it was about making of exposure to sunlight and warm. The streets themselves were lined with oak and pine logs, resting on wooden joists lying parallel to each other, and sprinkled with soil, sand and clay. They were quite narrow (about 2 meters), which made it rather impossible for carts to pass by. Circular street length was 417 meters, transverse streets a total of 780 meters.

Between the seventh and ninth transverse street was the square through which the eighth transverse street ran straight ahead to the gate. At the latter there was a small junction lined with logs to facilitate communication. The square, on the other hand, was not used for transport or communication, which was indicated by being coated with fascine and clay mixed with sand. Most likely it was used for public purposes and could accommodate all adult residents of the settlement. In the southern part of the square there was a small log building of an area of 20 square meters, associated with cultic activities or with the management of the stronghold.

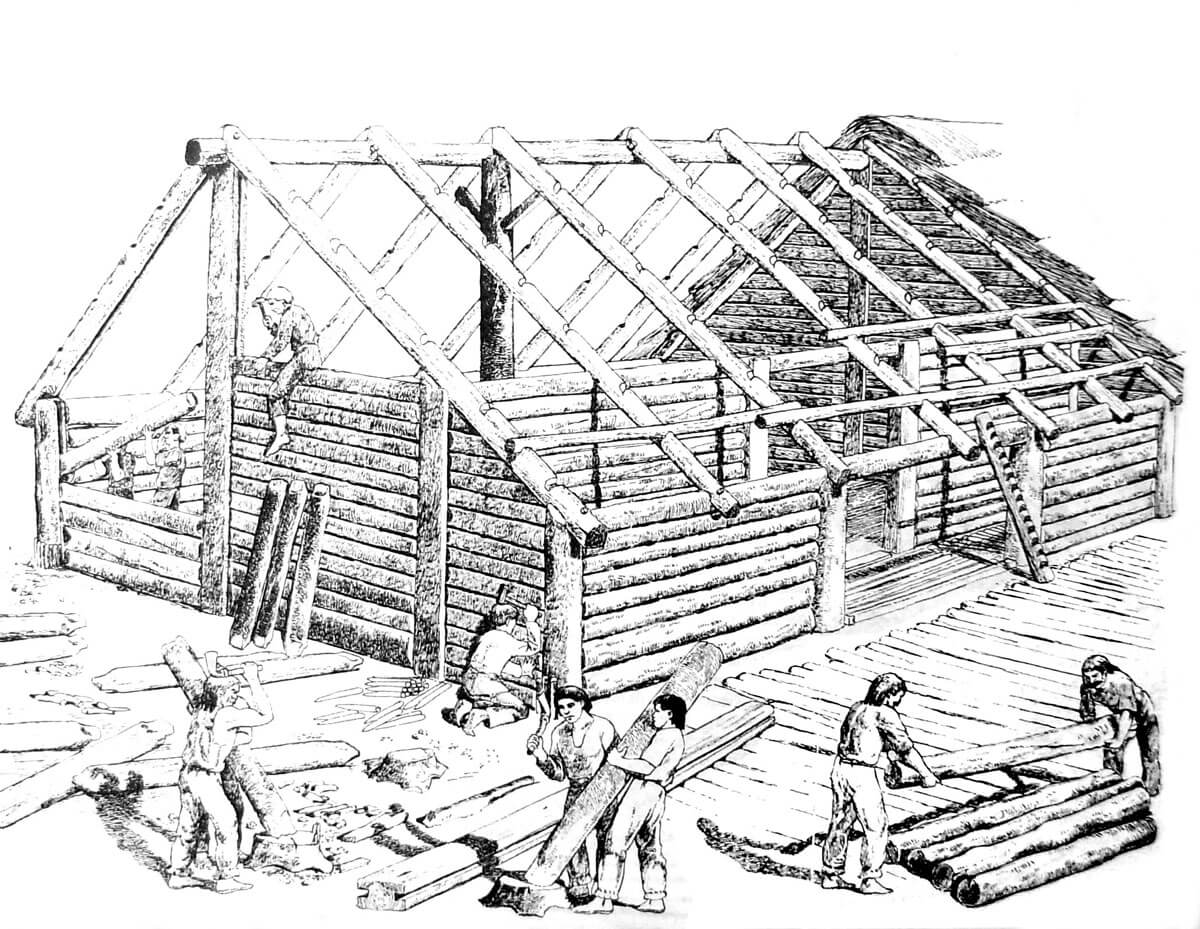

Biskupin households were built in a uniform post-and-plank technique. It consisted of sliding ends of planks into wooden poles with grooves, thus creating walls. The posts were reinforced on the sides with pegs, and the bottom was cut flat and dug into a soft ground. Four-sided oak intramural posts, in contrast to round pine corner posts, were further strengthened by poles interwoven through grooved holes, under which wooden crossbars were inserted to protect the posts from falling into the ground. Thanks to the post-and-plank technique, it was possible to build long wall sections using short logs, finally sealed with moss and clay.

The houses were usually about 8 meters wide and 9 meters long. Their floors were lined with logs and plastered with sand mixed with clay. Such a floor rested on a fascist grate made of birch and alder branches, isolating from a moist ground. All households were divided into two main parts: the main chamber and the so-called vestibule. In the main room with an area of about 60 m2 to the right of the entrance, where the oak threshold stood, an oval hearth of stones was located, and to the left a part for resting. The vestibule, incorporated along the entire length into the southern part of the house, was up to 2 meters wide and covered an area of about 18 m2. A wider entrance led through it to the room. The buildings were crowned with a gable roofs, probably covered with reeds. Arranged in rows with entrances in the southern walls, houses formed long dense blocks, shielded from the north-west winds and placed in such a way that around noon the sun was falling on the entrances, warming and lighting the interiors.

Inside the residential rooms, in their left part there were long joint beds. Household appliances and various shelves were arranged in other places. Above the hearths stood wooden devices like a spit. The entrances were blocked with braided walls of branches on wooden frames. Probably the vestibules, especially in the winter periods, were intended for animals, while the attic was used to store food and fuel supplies.

At a later stage of the settlement, perhaps due to the high pressure of ice floes, in the northern part, a fragmnet of the rampart and the circular street was moved inwards, and one house was liquidated, which reduced the first row of houses to three. In the younger phase of the settlement, a new, slightly narrower rampart was erected next to the old, damaged wall, but the breakwater circuit was widened. The ninth street was also directed straight to the gate, and the external access to the gate itself was taken along the outer side of the breakwater, directing it to the south-east. The access road was secured with double piles at the outer side. The area of the houses was reduced then, it were built of inferior wood, also using the log technique.

Current state

Biskupin is one of the most famous archaeological sites in Poland. It was discovered in 1933, thanks to melioration and irrigation works that led to a reduction of the level of waters in the Biskupin lake. The local population began to find antique objects, not realizing the importance of the discovery. Local teacher Walenty Szwajcer informed the local authorities, which, however, did not show any special interest. It was only to reach professor Józef Kostrzewski from Poznań, that the decision to start the research was made in the same year. Excavations in Biskupin, carried out in the interwar period, as well as after the war, were an example of the highest possible level of methodological research at that time, constituting a model to follow not only in Poland, but also abroad.

The stronghold in Biskupin contains full-size reconstructions of the defensive rampart, breakwater, gates, streets and residential buildings. In addition, you can visit the reconstructed neolithic homestead of the first farmers from 4,000 BC, the village of early Piast from the X-XI century, and a mesolithic camp with 8,000 BC. In addition to the reconstructions, in Biskupin there is a museum, and every third week of September there is a Biskupin festival there, including experimental presentations and reconstructive shows. The Archaeological Museum in Biskupin with the archaeological reserve can be visited throughout the year, every day from 8.00 to 18.00, only during the winter to dusk.

bibliography:

Kołos-Szafrańska Z., Szafrański Z., Z badań nad wczesnośredniowiecznym osadnictwem wiejskim w Biskupinie, Warszawa 1961.

Krajewski Z., Biskupin, osiedle obronne sprzed 2500 lat, Poznań 1983.

Soberski G., Warowny gród z epoki żelaza. Biskupin, Bydgoszcz 1991.