History

The Werder Castle first appeared in historical documents in 1465, although it was probably built slightly earlier, around 1430. It was an important checkpoint, guarding the nearby sea crossing between the mainland and the Estonian islands to the west. It also controlled coastal traffic on the route between the main commercial centers of Riga and Tallinn, as well as between the coastal episcopal seats of Haapsalu and Kuressaare.

The owner of the castle was the noble family von Uexküll, who held the local island as a fief from the Prince Bishops of Ösel-Wiek. The first record of the castle was associated with Wolmar and Heinrich, the sons of Conrad von Uexküll, who divided the family estate after father’s death. Werder Castle was then given to Heinrich (“dat slot up deme Werder”). The next owner of Virtsu was a certain Peter von Uexküll, recorded in 1509, and after 1534 his younger brother Johann, a vassal of the bishops of Tartu.

The castle was destroyed during the war between Margrave William of Brandenburg and Prince Bishop Reinhold Bekeshovede. The conflict was the result of the dissatisfaction of the bishop’s vassals, including the von Uexküll family, due to Reinhold Bekeshovede’s attempts to reduce their influence. Therefore, in 1532, in opposition they appointed the Margrave of Brandenburg as bishop. Werder Castle served as one of the few fortifications held by William’s supporters and was probably the main base of his fleet. For this reason, in 1533 it was besieged by 100 German mercenaries and 300 peasants of Reinhold Bekeshovede, but the attackers were chased away after burning several villages. The next raid in 1534 turned out to be stronger, and as a result, the castle fell. This event was crucial to ending the dispute. The rebellious vassals began negotiations with Prince-Bishop Reinhold and William withdrew.

Reinhold’s troops probably held the castle until the treaty with the rebellious vassals was concluded in 1535. Then they razed it to the ground, and the bishop handed the ruins over to Johann von Uexküll with a ban on rebuilding. William demanded that the castle be rebuilt or that Johann von Uexküll be compensated for the damages, but Bishop Reinhold did not agree, arguing that the castle was a house of robbers (“rawb haus”) and was demolished under the laws of war. The fate of the building was formally sealed by the decisions of the congress in Valmiera in 1536, during which it was decided not to rebuild the castle and to force the rebellious vassals to pay reparations. Despite this, Werder was probably restored to some extent by its owners for economic and residential use and could function at least until the war of 1558.

Architecture

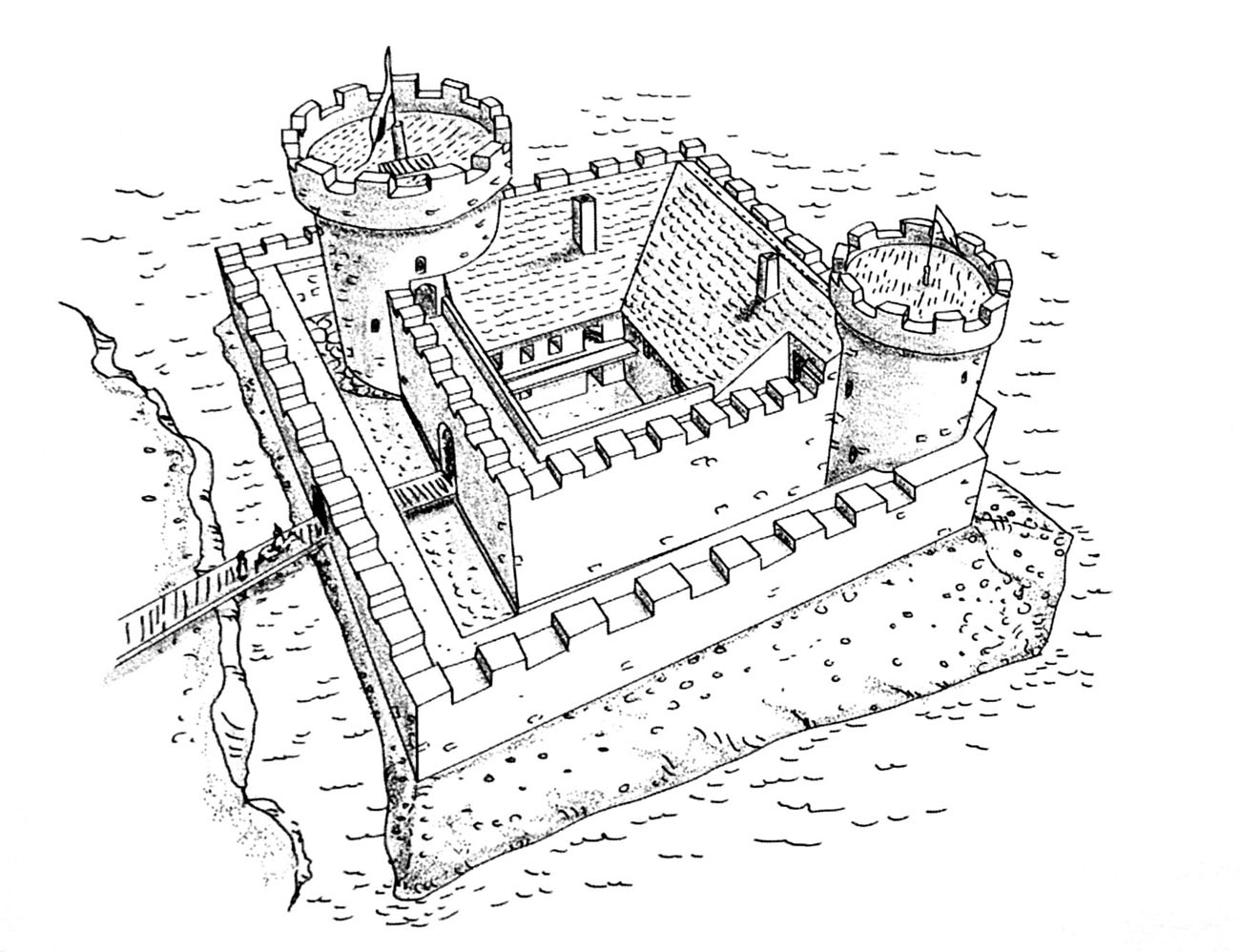

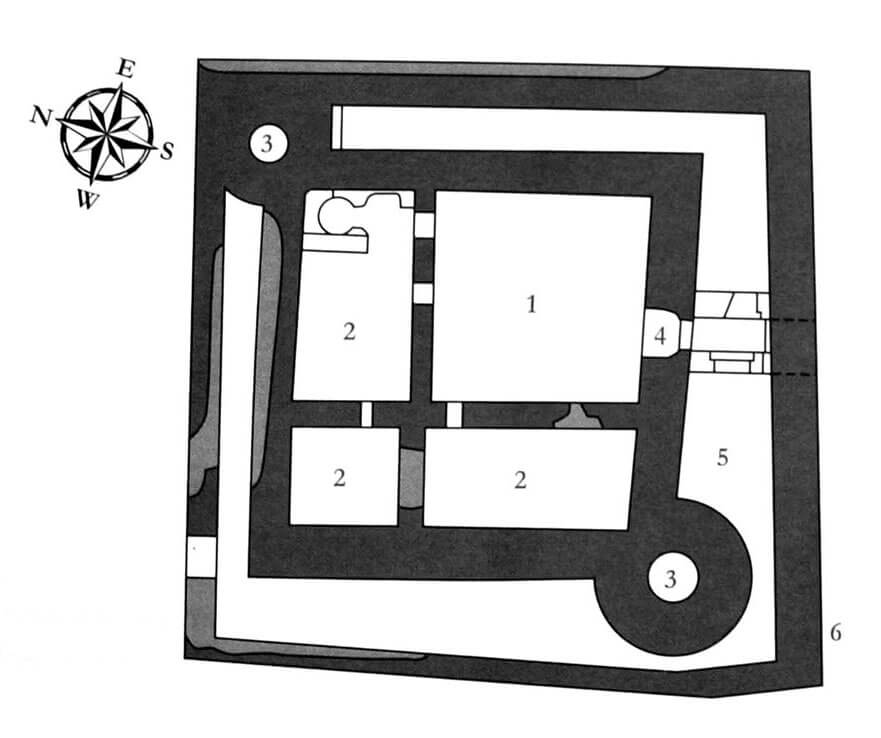

The castle was designed in such a way that it filled the entire area of a small island, located close to the land to the south. It had one almost perfectly square courtyard measuring 12.4 x 12.6 meters, surrounded by a massive wall 2.7 – 2.8 meters thick. An important element of the castle’s defense were cylindrical towers, adapted for the use of firearms, located in the north-east and south-west corners, of which the southern one guarded the entrance to the castle and was slightly larger. Both were strongly protruded in front of the curtains. Stone residential buildings were located in the northern and western parts of the courtyard, with the western wing built first, and then a shorter northern wing added to it. Both had a wooden communication porch added to the outside.

In the second stage of construction, the entire small castle with dimensions of 25.1 x 25.3 meters was surrounded by a low external wall, up to 2.8 meters thick. As it was made of exceptionally large and thick limestone blocks, often with dimensions exceeding 50 × 50 cm and about 40 cm thick, its primary purpose may have been to protect against storms or drifting ice floes. It was located just a few meters from the core of the castle, creating a very narrow zwinger. On the western and northern sides, the outer walls were thinner and the zwinger narrower. It was only 2 meters wide from the south-west tower, while the north-east tower was completely incorporated into it.

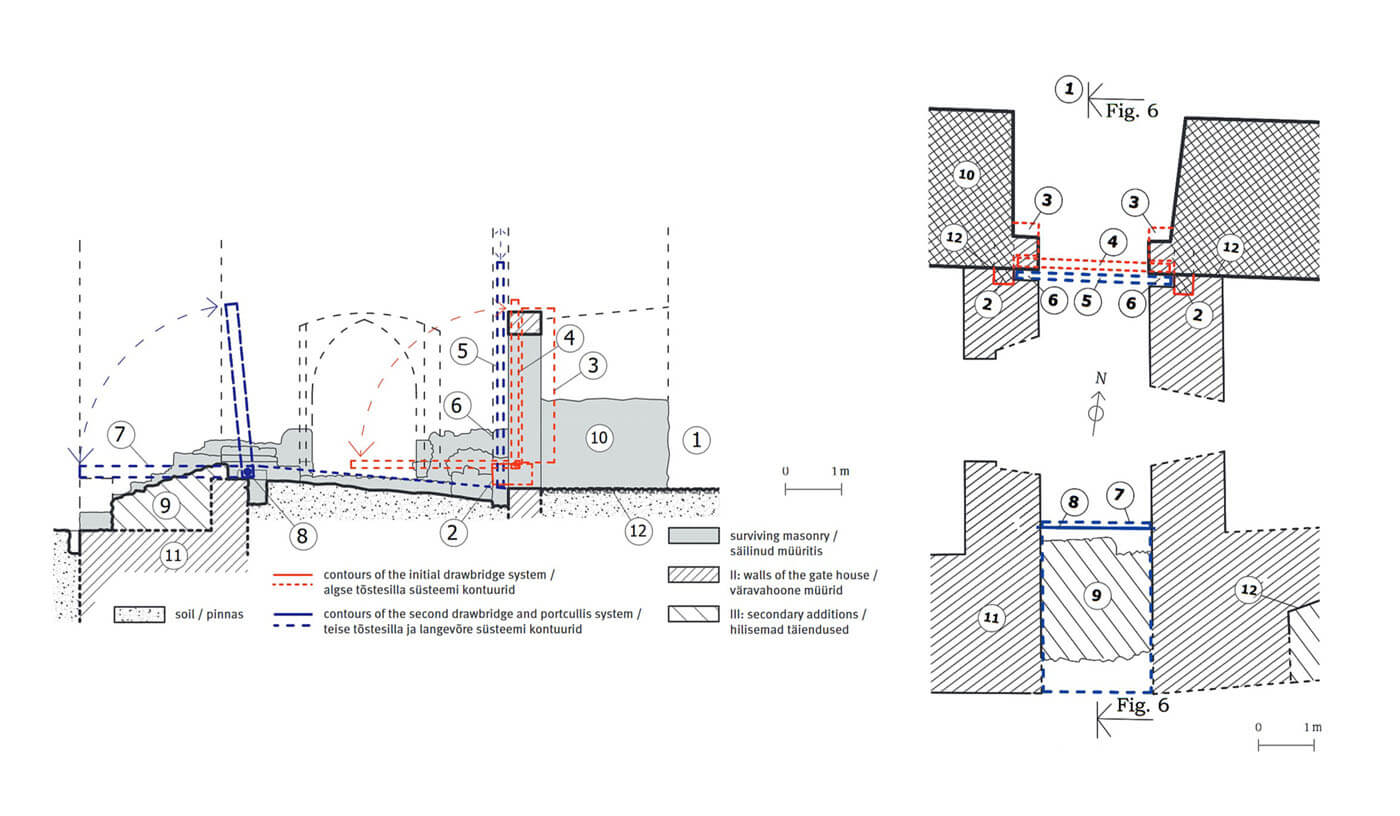

The gate to the courtyard was located approximately in the middle of the southern curtain. It was closed by a drawbridge, which was probably put into a recess in the wall, where it was mounted on two massive stones in the line of the portal. Since the expansion of the castle with an external wall, the gate in the zwinger area was preceded by a foregate, thanks to which the entire gate complex acquired dimensions of approximately 4.8 x 10.5 meters. In the western wall of the foregate there was a 2-meter-wide postern, providing access to the zwinger. There was probably a similar, but narrower opening on the opposite side. During the construction of the foregate, the old gate portal was transformed, the drawbridge was removed, and another drawbridge was created inside the foregate, unusually not over the moat, but over a pit in the line of the outer wall. In place of the old bridge, a portcullis lowered in guides was built, which would indicate the existence of at least one storey above the ground floor, needed to accommodate the mechanisms for its operation.

Current state

Fragments of the walls located by the sea, only a few meters high, have survived to this day. Unfortunately, in the last few decades they have been further degraded, especially from the water side. Among the stones is the base of one of the cylindrical towers, partially restored after archaeological research. Important monument are the relics of the gate with the remains of a rare drawbridge inside the foregate and an older one near the main wall. Admission to the ruins is free and easily accessible because the former island has been connected to the mainland since the 19th century.

bibliography:

Borowski T., Miasta, zamki i klasztory. Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Herrmann C., Burgen in Livland, Petersberg 2023.

Kadakas V., Archaeological studies of the gatehouse of Virtsu castle, „Archeological fieldwork in Estonia 2018”, Tallinn 2019.

Tuulse A., Die Burgen in Estland und Lettland, Dorpat 1942.