History

The Fellin castle was one of the oldest and most important strongholds of the Order of Livonian Brothers of the Sword, and in the town which developed at its foot, one of the most important trade routes and communication routes of Livonia crossed. The earliest information about Viljandi refers to the year 1211, when the hillfort of the Ests was besieged by the crusaders. Resistance had to be fierce, because there was a agreement, under which the stronghold retained some independence, but on condition of admission of Christian missionaries. In 1217, the Livonian Brothers brought to Fellin the first German merchants, which in the eyes of the Ests was a breach of the earlier compromise. In 1223, an uprising broke out, during which all the local Germans were murdered. Immediately after breaking the resistance of the local population, around 1224 on the order of the master of Livonian Brothers, Volkwin von Naumburg, the construction of athe first castle was begun, which was then raised to the rank of commandry. Its first known commander was a order’s knight Rikolf.

Fellin’s commanders, along with the commanders of Rewel, Goldingen, Paide and Marienburg, were part of the informal council of the highest dignitaries of the Livonian Order. The castle was one of six castles erected by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword before its incorporation in 1237 into the Teutonic Order. It was also one of the largest convents, as the number of its members in 1347 reached 36 brothers of knights, in 1451 there were 29 of them, and in 1554 – 12, never below the required by rule of 12. The great importance and large number of the local convent led to the construction of a brick conventual castle at the beginning of the 14th century. At the end of the 14th century and in the 15th century, it was considered one of the most strongly fortified in Livonia, and probably for this reason it was the place where the main treasury of the order was kept.

The invasion of Ivan the Terrible was a blow to the castle and the town. After a long siege, first the town was captured in 1560, and later the castle, which badly paid mercenary crew, refused to defend. In 1582, the town and castle buildings, ruined after the war, were occupied by Poles who in the following years lost them to Sweden. In 1602, another siege took place, during which the Polish troops recaptured Fellin, later losing it again after 20 years. None of the conquerors attempted to rebuild the stronghold, which lost its military importance and fell into complete ruin during the Great Northern War at the beginning of the 18th century.

Architecture

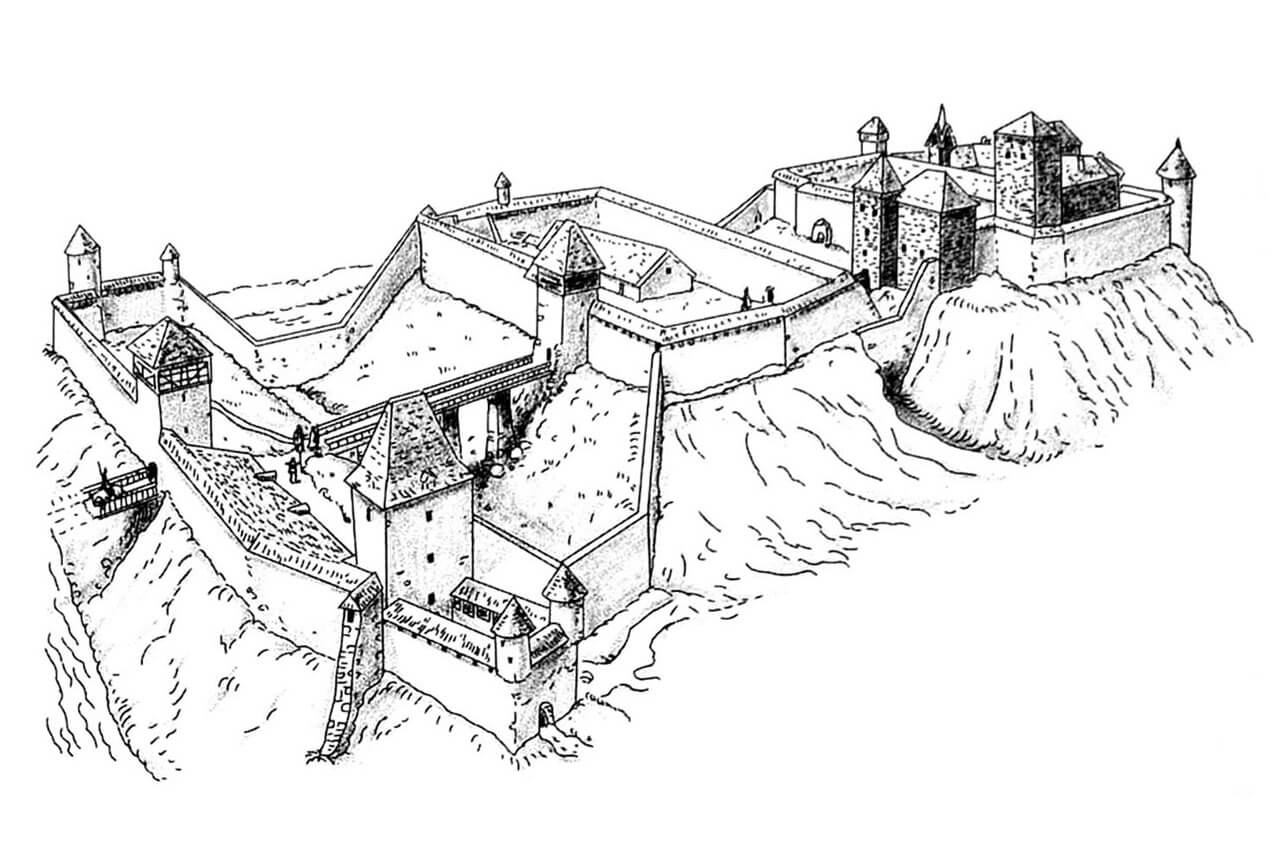

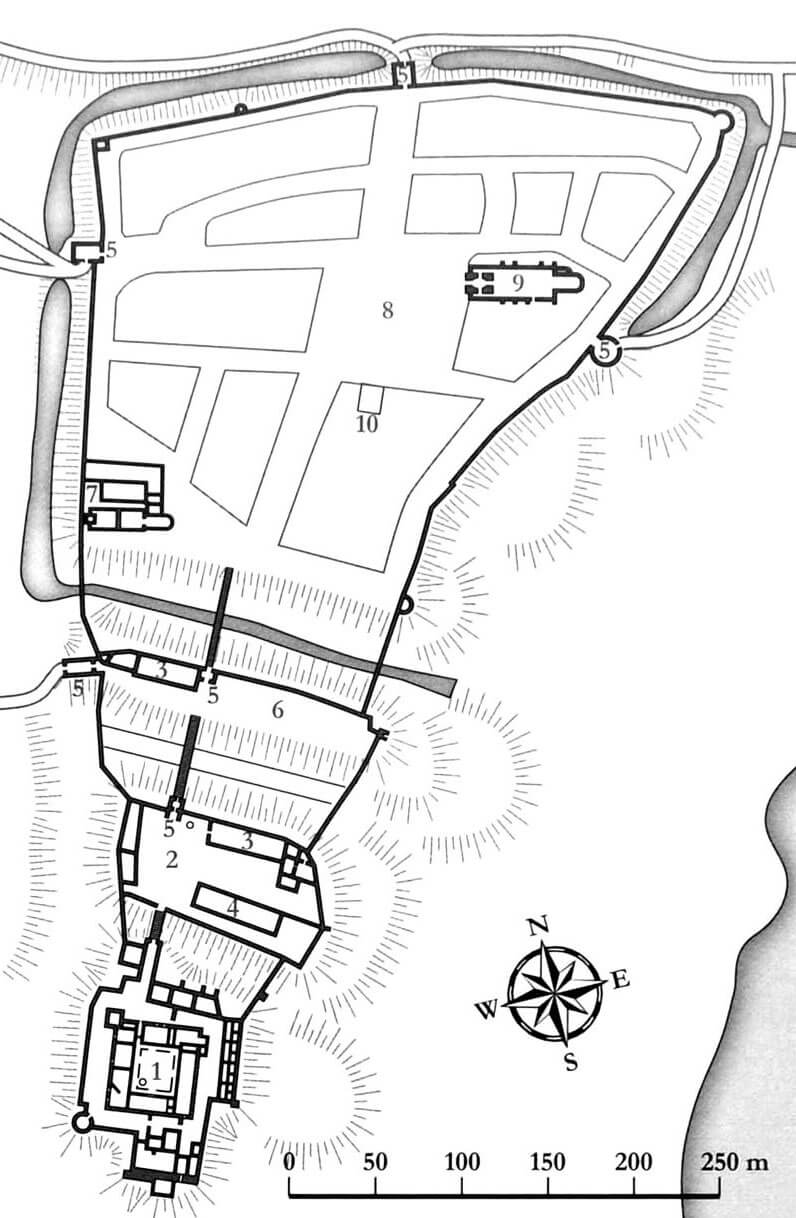

The castle occupied a vast elevation situated north-west of Lake Viljandi. In the east, protection was provided by high slopes descending towards the reservoir, while in the south and west, the slopes towering over the valley of the Valuoja stream, which entered the lake south of the castle. The gentlest approach was possible from the north, where the outer wards developed over time, and then the settlement and the town of Fellin. In the 14th century, the town was surrounded by defensive walls 1.2 km long, covering an area of approximately 10.2 ha and connected with the castle fortifications covering an area of 4.6 ha, which in total gave an extensive area of 14.8 ha. The town was surrounded by a wall on three sides, without its own fortifications on the castle side.

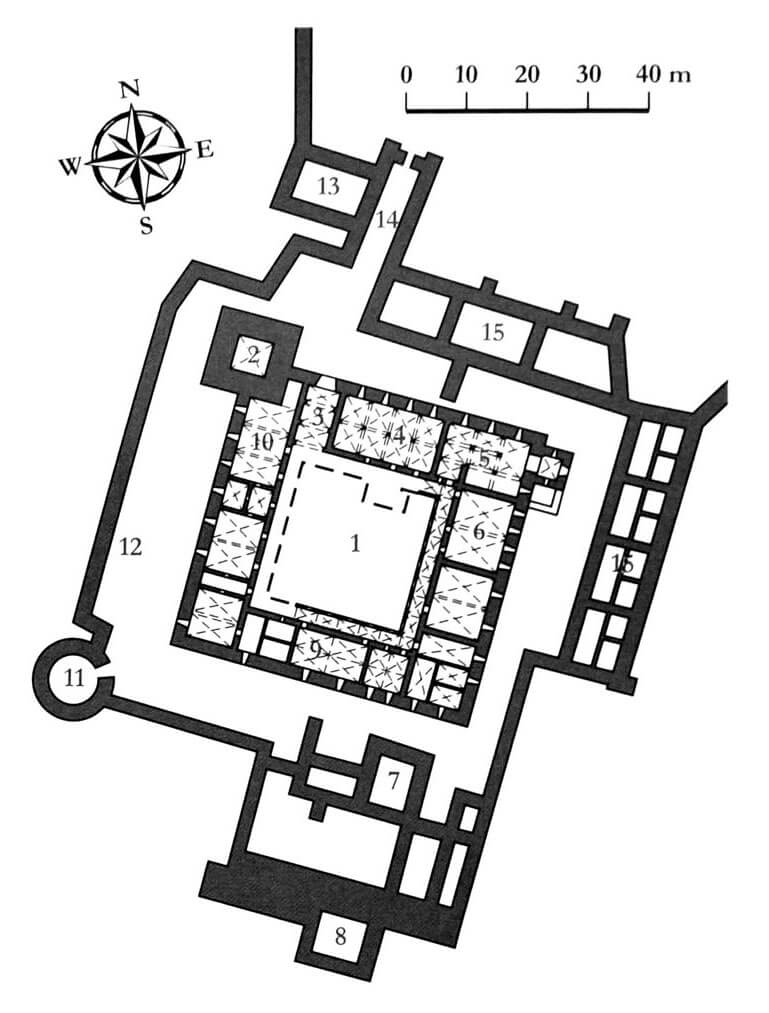

The oldest part of the castle was the huge main tower called “High Herman”, to which the seat of the convent was added from the south-east. It was a four-wing structure, forming a square in the plan with a side of 55 meters, in which the ground floor rooms had a utility function, while the first floor housed the most important rooms, connected with each other by an external, stone cloister. The chapel and chapter house were located in the northern range, the dormitory in the east, and the commander’s chambers in the west. The chapel was equipped with a four-sided projection on the eastern side, containing the presbytery part inside, while the refectory in the southern range was connected by an overhung porch with the dansker tower. It was located near the kitchen below, situated on the ground floor in the south-west corner. Apart from it, the ground floor also housed other utility rooms, such as a brewery, bakery, warehouses, etc.

The main tower was built on a square plan. In the lowest storey it housed a prison cell, and above, there were vaulted rooms in which crew could defend if the remaining parts of the castle were captured. It protruded strongly from the perimeter of the walls of the upper ward, ensuring control of the northern and western curtains, and also, thanks to the advantage of height, giving control over the entrance gate and the first inner bailey.

The defense of the upper ward was additionally strengthened on all sides by the external wall, creating a spacious zwinger on which there were buildings of individual Teutonic officials and monastic priests, as well as economic buildings, e.g. stables. In the late Middle Ages, this wall was reinforced in the south-west corner with a cylindrical tower, probably adapted to the use of firearms.

The upper ward from the north was protected by two fortified baileys, separated by ditches, drawbridges and gate towers. The most powerful of them was the north-west gate on the outer bailey, equipped with a foregate with two bartizans in the neck, facing the foreground, thus providing entry to the castle without passing the town. A passage led to the latter in a four-sided gatehouse on the northern side. The fortifications of the outer bailey were connected with the town defensive walls and with the inner baily, because the walls even run along the bottom of the ditches.

Current state

Today, there is little to see from the once-powerful castle. There is one of the walls of the upper castle, the remains of the castle gate, the lower part of the dansker tower and a fragment of the middle castle wall. The rest are foundations and few small relics. The castle’s moats separating the upper, middle and lower castle are visible. The castle ruins are now a frequent place for outdoor events.

bibliography:

Bernotas R., New aspects of the genesis of the medieval town walls in the Northern Baltic Sea region, Turku 2017.

Borowski T., Miasta, zamki i klasztory. Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Herrmann C., Burgen in Livland, Petersberg 2023.

Tuulse A., Die Burgen in Estland und Lettland, Dorpat 1942.