History

Varbola was one of the largest strongholds and trading centers of the Baltic population of the northern part of Livonia in the 11th-12th centuries. It was one of the two main centers of the Harria (Harjumaa) province, the eastern part of which was to be subject to the Lohu stronghold, and the western part to the seat in Varbola, according to the chronicler Henry the Latvian. The inhabitants of the stronghold (“warbolenses”) were to constitute a significant political and military force. Henry the Latvian also recorded the “Castrum Warbole”, besieged in 1211 for several days by Mstislav Mstislavich the Daring of Novgorod, who withdrew after receiving a ransom. During the crusades, the inhabitants of Harria pursued different policies and did not act in an organized manner, which ultimately contributed to their defeat. Volkwin Schenk, the master of the Livonian Order, ordered the adoption of Christianity and the capture of the hostages, released only at the request of the envoys of the Danish king Valdemar II, who in 1238 took control of the northern part of Livonia.

In the second half of the 13th century, Varbola lost its importance due to being cut off from the economic base, changing the layout of the trade network and the decline of the crafts in favor of the newly emerging towns. Moreover, the local population was subordinated to the conquerors under the introduced vassal system and, as a result, lost its political importance. Although the stronghold was sparsely inhabited, it lost its status as a center where developed social life took place. Presumably due to the lack of material resources and labor, the fortifications of the stronghold fell into neglect. It were far from the borders of Livonia and therefore of no importance to the new rulers, and perhaps even considered a threat to their rule. The wooden elements of the stronghold had to degrade after a maximum of about 20-30 years if no repairs were made. The last renovation works on one of the castle gates were found around the mid-13th century.

In 1343 on Saint George’s Eve, an anti-Christian and anti-German uprising of the native population broke out in the province of Harria, which then spread to the neighboring regions of Livonia. According to Henry the Latvian, at the beginning of the fighting the Aesti were to refortify two strongholds, one of which was probably Varbola. For a short time, the uprising completely changed the political situation and social organization in the region, and again provided the old Estonian strongholds with their former support, both in terms of population and economy. This made possible to carry out necessary repairs or reconstruction. However, after the uprising was suppressed, the stronghold ceased to function and the fortifications were probably demolished. The failure of the uprising also resulted in the escape or resettlement of the inhabitants in the second quarter of the 14th century. Judging by the coin finds, only the well in the courtyard could have been used occasionally, perhaps for votive purposes. In the 15th century, a cemetery was established on the former ward of the abandoned stronghold.

Architecture

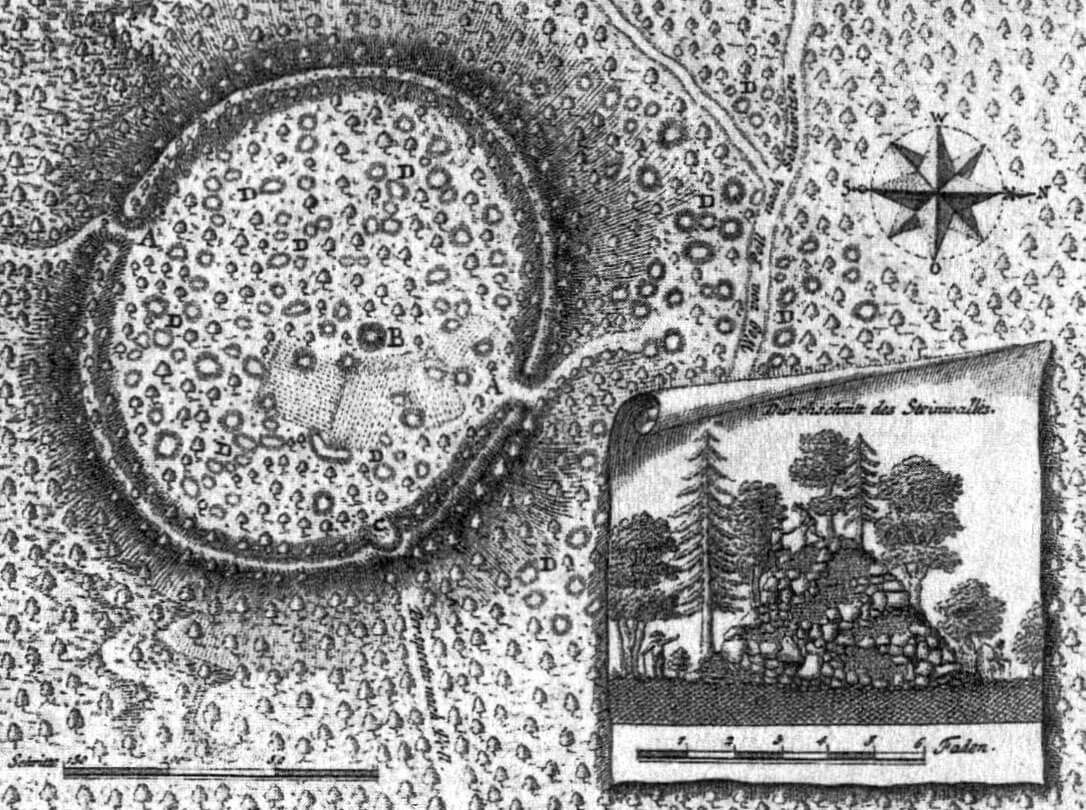

The stronghold was founded on raised terrain, among forested and also wet lands in the Middle Ages, with only a limited amount of agricultural land. The plan of the fortifications of the stronghold was similar to an oval, covering an area of approximately 2 ha. The length of the defensive perimeter was about 580 meters, the height from the outside was at least 7-10 meters and at least 2-7 meters from the side of the inner ward. The width of the earth rampart at the base was about 25-30 meters. It was faced on both sides with a wall of limestones, split into flat fragments and laid without the use of mortar. The top of the wall must have had some form of breastwork, protecting the defenders on the wall-walk in the crown of the rampart. It was probably a wooden structure.

The entrance to the courtyard was through two gates, located on the west and east, more or less opposite each other. Both gates had the form of a passage 6 to 8 meters wide, created by a break in the ramparts. It could be protected by tower-like structures, because on the ground floor the stone walls of the gate passages were reinforced with vertically placed timber logs. It protected the unmortared wall structure and probably formed the basis for the wall-walk placed over the passage, at the level of the wall’s crown. If there was a tower above, it was probably not high, maximum one storey higher than the neighboring fortifications. In front of the western gate there was a kind of foregate, turning towards the south. A similar construction could have been used at the eastern gate, only turning north.

In the center of the courtyard there was a 13-meter-deep well, and around it there were about 90 buildings equipped with stone hearts. Most of these houses were built on a rectangular plan in a log structure, i.e. made of horizontally arranged timber connected at the corners. Some buildings had floors and foundations made of limestone slabs. The houses usually had one large room, but sometimes smaller extensions of an economic nature were built next to them. The window and entrance openings were probably small to protect against the cold.

Current state

Parts of the stone and earth ramparts of the stronghold have survived to this day, with virtually the entire circumference and a height of several meters. Most of their stone part collapsed and the earth was scattered to the sides. A fragment of the southwestern rampart was partially reconstructed, and the lower part of the western gate was also rebuilt. Admission to the fort is free. Its former courtyard is partially overgrown with trees, but the shape of the structure is still visible. There is a tourist path at the top of the rampart, accessible via modern stairs. There are also several benches, replicas of medieval war machines and an information board. Approximately in the middle of the site, a large pit of a former well or water tank is visible.

bibliography:

Laid E., Varbola Jaanilinn, Tartu 1939.

Mägi M., Bound for the Eastern Baltic: Trade and Centres AD 800-1200 [in:] Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World, Firenze 2016.

Valk H., The Fate of Final Iron Age Strongholds of Estonia, “Muinasaja teadus”, 24/2014.