History

The first information of the church of St. Olaf, one of the two parish churches of the city of Tallinn (German: Reval), was recorded in documents in 1267. Then the Danish Queen Margaret Sambiria transferred its right of patronage to the nearby Cistercian nunnery. The church received a rare dedication from the king of Norway and Catholic saint, Olaf II Havaldsson, because it was built on the market square of Scandinavian settlers, originally outside the oldest core of the city. It was incorporated into the city defensive walls in the first half of the 14th century. It was then that construction work on the vaults was also completed (one of the bosses had the date 1330).

In the first quarter of the 15th century, an impressive Gothic chancel with a sacristy was added to the church, the construction of which was probably carried out by local master builders. However, in 1433, the church was damaged by fire, which initiated renovation and a thorough reconstruction of the nave, as a result of which it acquired the form of a basilica. Construction works, carried out from 1436 under the supervision of the Tallinn master Andreas Kulpesu, were continued by masons Olef Murmester and Hans Howensten, recorded in documents in 1442. In 1439, the reconstruction of the western tower began, then in the years 1446-1448 master Johan Grunde placed a late Gothic cupola on it, and in the period 1448-1449 finishing works were carried out on the floors and the glazing of the windows of the nave. At the end of the 15th century, a chapel was built next to the southern aisle, and the end of the medieval construction process was the construction of the late Gothic St. Mary’s chapel next to the chancel in 1512-1521, founded by the local merchant Hans Pawels on the site of the chapel from the beginning of the 15th century.

From 1524, when the ideas of the Reformation reached Tallinn and gained popularity, the church began to serve the Protestant community. Under the influence of iconoclasm, a turbulent crowd of townspeople devastated the interior, destroying many paintings, altars, sculptures and other medieval furnishings. The building was also destroyed by fires caused by natural factors. For example, in 1625, the church tower was struck by lightning during a storm, which spread the fire to the copper and lead-covered roofs of the church and then to the interior. Just a few days after the fire, the townspeople were to collect funds for renovation, thanks to which the functionality of the building was restored by 1628. The renovation of the tower took longer, because it was not until 1648 that the wood for the scaffolding was cut, and in 1651 the reconstruction was completed. Subsequent, less dangerous and quickly extinguished fires broke out after lightning strikes in 1693, 1698, 1707, 1719 and 1736. In the summer of 1740, a phenomenon resembling smoke was noticed on the tower, but it turned out to be a large swarm of mosquitoes.

In 1820, during an apparently weak storm, lightning struck the tower once again. The fire spread so quickly that in a short time the large tower cupola along with the four corner turrets burst into flames, then collapsed on the neighboring house and spread the fire to the nave of the church. All the equipment inside burnt, but luckily, after about four hours, heavy rain fell, which helped extinguish the fire and prevent structural damages to the building. The renovation of the church took another twenty years. During World War II, unlike the parish church of St. Nicholas, church of St. Olaf fortunately avoided more serious damages.

Architecture

The oldest church from the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries was probably a short building with a massive four-sided tower on the western side and a small, perhaps square-shaped chancel on the eastern side. The whole structure was probably similar in form to the 13th-century St. Mary’s church of Visby, which could have been a model for builders from Tallinn. The tower was certainly the dominant feature of the building, with walls up to 3.2 meters thick on the ground floor, opened to the nave with a large semicircular arcade. Originally tower could have had a defensive function, because the church remained outside the city walls until the first half of the 14th century. This role lost importance after the northern settlement of Scandinavian merchants was incorporated into a growing charter city. The church area was then enclosed from the west and east by long streets, the eastern one of which led from the central part of the city with the market to the Sea Gate in the north.

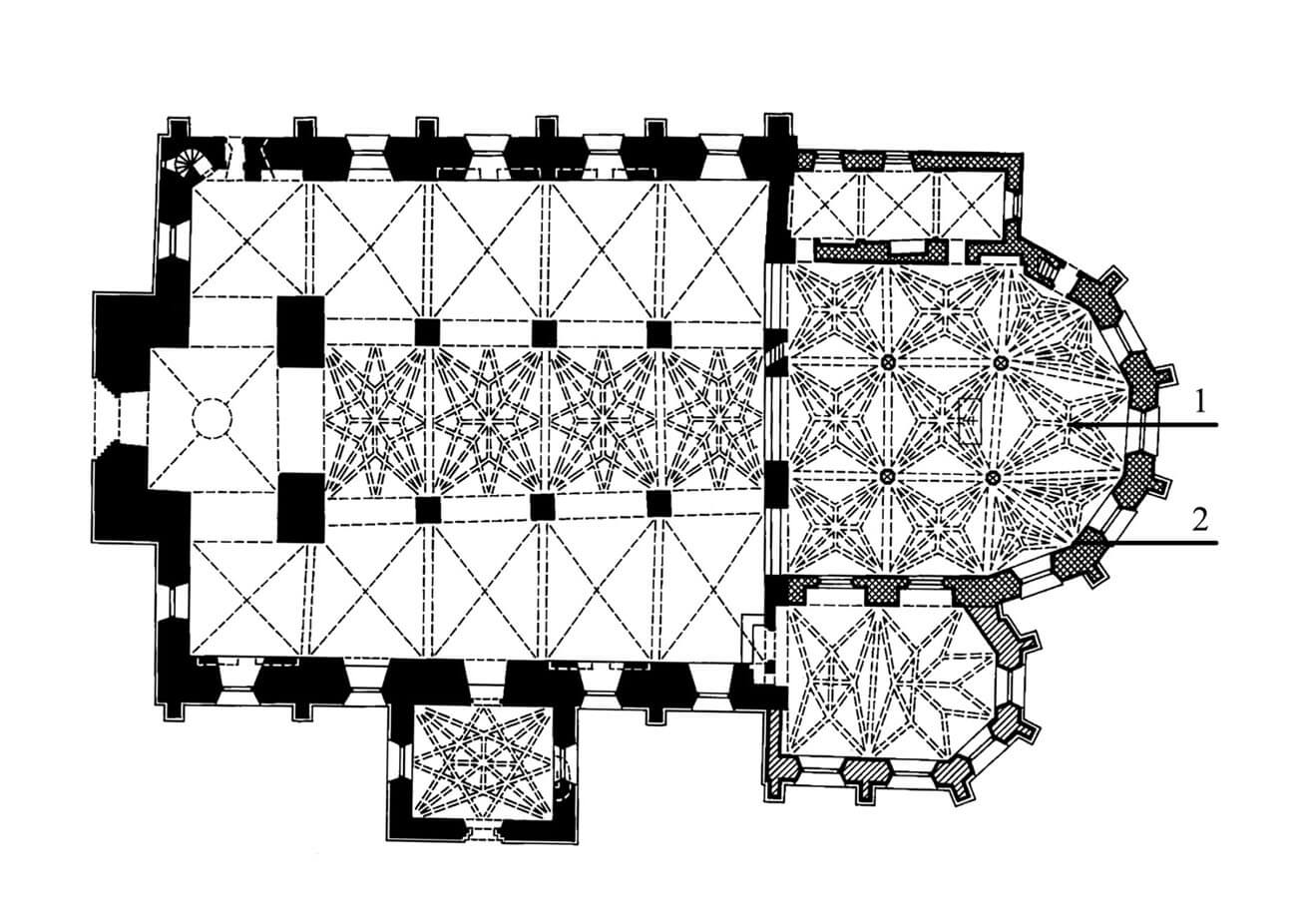

In the 15th century the church had the form of a basilica with central nave and two aisles, on the eastern side closed with a short, but wide chancel with a polygonal closure (seven sides of a dodecagon). From the west, on the extension of the nave, the older four-sided tower was left, flanked from the north and south by the extreme bays of the side aisles. On the northern side of the chancel there was a three-bay sacristy, while on the south a late Gothic St. Mary’s chapel was built in the first quarter of the 16th century, which was a smaller version of the chancel with an aisleless interior and a three-sided closure in the east. Moreover, in the middle of the longer facade of the southern aisle, a quadrilateral chapel was built at the end of the 15th century.

From the outside, the walls of the nave, chancel and St. Mary’s chapel were surrounded by a regular rhythm of stepped buttresses. Characteristically, the two western corner buttresses of the aisles were not placed at an angle, or even in the corners themselves, but perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the nave and slightly away from the facade. The buttresses of St. Mary’s Chapel were distinguished by canopies with pinnacles, set in recesses with trefoil heads, which probably originally held figures. Further pinnacles were placed on the mono-pitched roofs of the chapel’s buttresses, so that they seemed to be protruding through the buttresses. Moreover, above them, under the roof eaves,an unusual frieze of small bas-relief pinnacles was made. Between the buttresses of the nave, the chancel and the chapel, a large pointed windows with tracery were inserted, most of them three-light. Only the axial window of the chancel had four-light tracery, certainly to stand out the most important window in the church, located on the axis of the main altar.

The interior of the central nave was divided into four bays. Most of them obtained an irregular, trapezoidal form due to the need to adapt the Gothic chancel with a narrow central part to the older and wider tower in the west. The central nave was covered with stellar vaults with an eight-arms, mounted on high suspended corbels. The aisles were separated from the central part by four-sided pillars with moulded cornices in the capital’s zone, on which pointed, chamfered arcades were placed. Similar arcades with impost cornices connected all the aisles with the chancel. Cross vaults were used in the side aisles of the nave. The bays in the southern aisle were made irregular due to the need to adapt to the narrowing central nave. The aisles gained one more bay than the central nave, which made the western tower somehow incorporated with the nave. The interior of the chancel was divided into three aisles by two pairs of slender, octagonal pillars. Above them four-pointed stellar vaults were built, except for the extreme bays of the side aisles in the eastern end, where the three-pointed stars had to be used in the triangular bays. The ribs were finished on the peripheral walls and pillars with pyramidal consoles, placed right next to larger consoles supporting moulded arch bands. The neighboring St. Mary’s Chapel was also covered with a stellar vault, but the ribs ended there on the peripheral walls with undercuts.

The late Romanesque tower was dismantled in the second quarter of the 15th century to a height of approximately 30-31 meters. On its ground floor a new main portal was inserted from the west, and above it a magnificent pointed-arch window reaching 27.5 meters high was built. The portal received rich moulding of jambs and a pointed archivolt, based on cornices in the capital’s area. The window was filled with five-light tracery with trefoil motifs and a rosette in the archivolt. Then the tower was raised and on the upper two floors rows of blendes and windows with pointed heads were set. At the end of the work, the tower was topped with a slender and very high spire, probably reaching about 115-125 meters, modeled on numerous cupolas of Northern European churches, used especially in Hanseatic cities. The spire had the form of a pyramid with gables in the lower part, located on each side of the world. These gables were necessary to ensure a smooth transition from the prismatic part of the tower to the octagonal pyramidal spire. The spire’s structure was made of wood, covered with tin sheet metal on the outside.

As in every medieval church, also in St. Olaf there was a close connection between architecture and the cult of saints and the development of the liturgy. At the beginning of the 16th century, in addition to the main altar, there were as many as 25 side altars in the church, funded by wealthy townspeople and guilds. Most of them were placed in the side aisles of the chancel and in the eastern ends of the nave. The desire to show status and wealth also meant that benches were added to the church. Also more important personalities were buried in the chancel, were bas-relief tombstones were placed. Initially, representatives of the city council had their own benches and tombstones, then merchants and other donors. Church treasures were kept in a wall recess closed with an iron grate, located in the south-eastern part of the chancel. Two blind traceries with trefoil motifs were created on its sides, and it was topped with a gable with tracery filling in the form of a cinquefoil and bas-relief crockets and fleuron on the edges.

Current state

Church of St. Olaf (est. Oleviste Kirik) is currently one of the most important sacral buildings in the city preserved from the Middle Ages. Although it was repeatedly destroyed by fires, the vast majority of its Gothic walls from the 15th century have been preserved to this day. The exception is the southern chapel next to the aisle, which was completely demolished after the fire of 1820 and rebuilt from scratch in larger dimensions, although its external form stylistically refers to the rest of the building. Similarly, the shape of the western tower’s spire, although is the result of a 19th-century reconstruction, refers to the soaring, slender Gothic spires. It differs from the late medieval one only in the presence of four corner turrets and the lack of gables in the lower part, but its height is similar to the original one. Currently measured by a surveyor it is just over 123 meters high (it is worth noting that the information found in the literature that St. Olaf’s church has the tallest tower in Europe is untrue, resulting from a mistake of early modern writers).

bibliography:

Engelhardt M., Aus dem Leben der St. Olai-Gemeinde, Tallinn 1938.

Hein A., Linna auw ninck illo. Olevistest ja tema tornist, “Tuna”, 4/2014.

Mänd A., Oleviste kiriku keskaegsest sisustusest ja annetajate ringist, “Acta historica Tallinnensia”, 20/2014.

Neumann W., Nottbeck E., Geschichte und Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Reval, Zweiter Band, Reval 1904.