History

Construction of the church of St. Nicholas began in the 1230s and was completed around the last decade of the 13th century. It was founded by Westphalian merchants who came to Tallinn from Gotland and settled on the southern side of the oldest part of the city. A nave with two aisles, a chancel with a sacristy, and a low tower were then built. The settlement of German merchants was not yet included in the city’s defensive walls, so the church could have had defensive significance, as one of the few stone buildings with massive walls. When the city was fully surrounded by walls in the 14th century, the church’s defensive role lost its importance, but it still served as one of Tallinn’s two parish churches.

In the first half of the 14th century a northern porch was added to the church. In 1342, the chapel of St. Barbara was first recorded in documents, probably originally a charnel at the neighboring cemetery. It ceased to play this role at the end of the 14th century, when the late Gothic reconstruction of the church began. The second chapel of St. Matthew was built in the 1470s. Then, in the first quarter of the 15th century, a Gothic choir with a polygonal ambulatory and a new sacristy were built, and the central nave was raised, giving the church the form of a basilica. These works were probably carried out between 1405 and 1420, which was a very fast pace considering construction activity in the Middle Ages.

In 1481, a new main altar was placed in the church, ordered from the workshop of Hermen Rode in Lübeck, and a year later the first organ was installed inside, replaced around 1490 by new ones, constructed by a certain Herman Stüve from Wismar. At the same time, renovation and construction works were still in progress, as the accounting book kept since 1465 recorded payments to master masons, stonemasons, stone crushers, blacksmiths, carters, carriers, porters, sculptors, glaziers, painters, carpenters, lime kilns workers, scaffolding fitters and ordinary workers. Interestingly, women also took part in the building process, usually working in pairs or foursomes on unknown tasks. Perhaps they were related to the new roof of the central nave of the church, which was founded in 1488, or to the plastering of the tower’s facades that was carried out just earlier. In the years 1484-1492 the chapel of St. Matthew was rebuilt and enlarged, presumably under the supervision of the master builder Andreas Kam, who worked on the church from 1488 until his death in 1491. Then, in the years 1510-1515, with the participation of stonemason Andreas Mor and his assistants, the tower was raised, and at the end of the work topped with a late Gothic dome.

Church of St. Nicholas was one of the few temples in Tallinn that was not devastated during the Reformation in 1523-1524. The parish council decided to pour molten lead into the church’s locks to prevent the angry crowd from breaking into the church. However, in 1533 the church suffered its first destruction as a result of a fire, and in 1577 it was damaged during the siege of the Moscow army, whose shelling damaged the roof structure. Repair works were also necessary after the fire of 1624, especially in the area of the northern aisle.

In the years 1685-1696, under the supervision of the city builder Georg Winkler and the master carpenter Hans Dorch, the tower’s structure was strengthened, it was once again raised, and the Gothic helmet was replaced with a Baroque one. Further renovations of the tower took place in 1768 and 1833, and the choir and chancel were also restored in 1846-1850 due to noticed cracks in the walls and vaults. The Second World War brought heavy losses to the building. In 1944, the church was bombed by the invading Soviet troops. Most of the interior was destroyed, but fortunately the most valuable works of art were removed and secured in time. Reconstruction began in 1953 and was completed with the opening of the museum in 1984.

Architecture

Church of St. Nicholas was built in a settlement of German-speaking merchants, located on the southwestern side of the oldest core of the city, and at the same time on the southeastern side of the castle hill. In the first quarter of the 14th century, together with the neighboring buildings, it was incorporated into the defensive walls of the main part of the city. Its western facade faced the street running parallel to the defensive wall. The free space in the north was used for a church cemetery with a custodial house, while a rectory house was located in the south. On the eastern side of the church, in the 14th century, dense residential buildings developed, divided into regular plots.

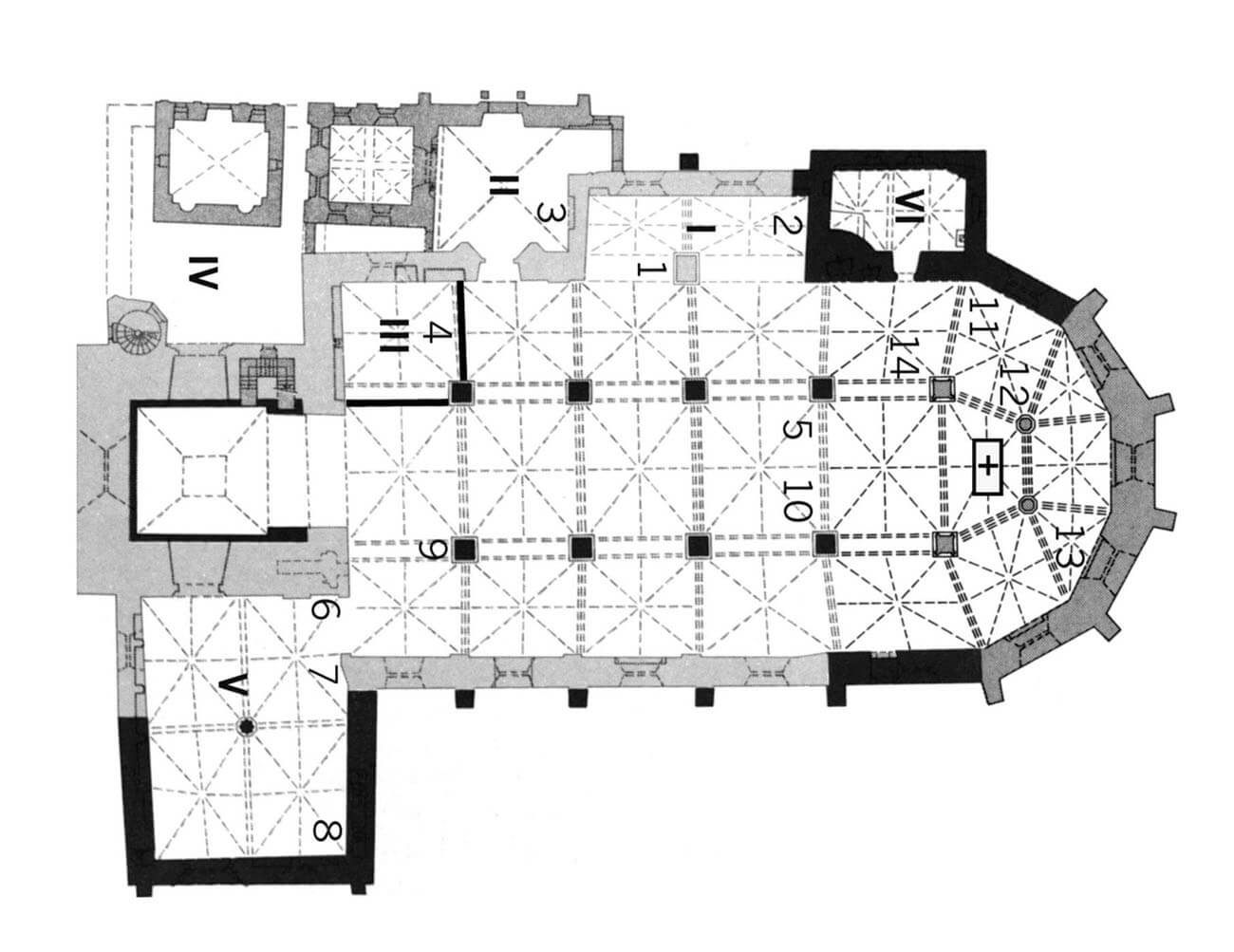

In the second half of the 13th century, the church had a nave with two aisles and a relatively small chancel on the eastern side, built on a square-like plan, and a sacristy located on its northern side. From the west, the church already had a low tower on a square plan with sides of 15.3 meters. In the first half of the 14th century, the church was enlarged with the chapel of St. Barbara, at the end of that century moved to the northern side of the nave, where it had the form of a two-bay annex opened with arcades to the aisle. A porch was also built next to the northern aisle. In the 1370s, a chapel of St. Matthew was built near the southern wall of the tower, originally small in size and with a single-space interior. The late Romanesque nave had vaults over the aisles, supported by internal pilaster strips. A small chancel may also have been vaulted, but there was probably a wooden ceiling or an open roof truss above the central nave.

In the first quarter of the 15th century, the church was thoroughly rebuilt. A Gothic chancel with a polygonal ambulatory and a two-bay sacristy were then built. The central nave was raised and pierced with windows over the aisles, thanks to which the church form was transformed into a basilica. At the end of the 15th century, the northern porch was enlarged and transformed into the chapel of St. George. The chapel of St. Matthew was also enlarged, which then acquired a more impressive form of a two-aisle building with a vault supported by a central pillar. In the years 1510-1515, the tower was raised and topped with a late Gothic cupola made of copper sheet, in the corners of which four turrets were added at the base.

In the 15th century, the church acquired a uniform form with the side aisles passing smoothly into the ambulatory. The whole was of the same height with a common roof and was surrounded from the outside with stepped buttresses, between which high, pointed windows of the aisles and ambulatory were created. In the central nave and choir smaller windows were inserted, also pointed, pierced on the smooth surface of the walls. The facades of the upper parts of the tower with semicircular high blendes had a more decorative form. The southern gable of the chapel of St. Matthew was decorated with lancet blendes with a pyramidal arrangement, with the archivolt of each blende filled with trefoil tracery. The annexes on the northern side of the church were probably also topped with similarly decorated gables. The entrances to the church were directed mainly to the north, because there was a busy street in front of the cemetery there. The pointed and moulded portal was located in the ground floor of the tower and in the aisle in the second bay from the west. On the opposite side of the nave, there was an early Gothic portal with a trefoil in the archivolt from the 13th century.

The interior of the church was divided in the central nave and aisles of four bays each, rectangular in the central part, similar to squares in the aisles. The bays in the ambulatory were trapezoidal and rhomboid, while the choir and chancel were divided into one rectangular bay and a closing bay with a trapezoidal plan. The division into aisles in the 15th century was provided by four-sided pillars with cornices in the capital zones, on which pointed, slightly chamfered arcades were placed. The plinths of the pillars were also chamfered. The old pilaster strips in the aisles ceased to fulfill their original function, because the division into bays in the late Gothic nave was slightly shifted and the axes of the pillars were not aligned with the axes of the pilaster strips. The arch bands of the late Gothic vaults were supported on corbels, suspended on the walls and pillars between the aisles.

Current state

Church of St. Nicholas (est. Niguliste Kirik) is one of the main medieval sacral monuments of Tallinn, all the more valuable because all the equipment saved during World War II returned to the church. However, the building did not escape damages, especially during World War II, due to which the western and central parts of central nave had to be reconstructed. The chapels on the northern side of the church were rebuilt in the early modern period, and the tower dome, located on the 17th-century top floor, also has a Baroque form. The window frames were transformed in the mid-19th century, and most of the inter-nave pillars and vaults had to be rebuilt from scratch in the 20th century. The original vault with its support system survived World War II in the chapel of St. Matthew, one of the few completely intact rooms in the church.

Currently, the church is intended as an exhibition hall for medieval art under the care of the Estonian Art Museum. Because its interior has excellent acoustics, it is also used as a concert hall. The most valuable element of medieval furnishings is the altar made between 1478 and 1481 in the workshop of master Hermen Rode. In the chapel of St. Anthony (originally dedicated to St. Matthew), a painting by master Bernt Notke from Lübeck has been preserved, depicting a dance of death performed at the end of the 15th century. Among the architectural details, several Gothic portals, a wall niche with a tracery archivolt in the southern part of the ambulatory and a number of other wall niches have survived.

bibliography:

Kala T., Ergänzungen zu den an der Nikolaikirche in Reval/Tallinn in der zweiten Hälfte des 15. und dem ersten Viertel des 16. Jahrhunderts arbeitenden Meistern und Arbeitern, “Baltic Journal of Art History”, 2/2010.

Lumiste M., Kangropool R., Niguliste kirik, Tallinn 1990.

Markus K., Tooming K., Hiliskeskaegsest Niguliste kirikust hingepalvete ja eneseeksponeerimise peeglis, “Acta Historica Tallinnensia”, 16/2011.

Neumann W., Nottbeck E., Geschichte und Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Reval, Zweiter Band, Reval 1904.