History

Dominican friary dedicated to St. Catherine functioned in Tallinn probably from 1229-1239, and in new location after a short break from 1246, when, by the decision of the provincial chapter of the order held in Ribe, Prior Daniel of Visby was sent to Tallinn together with eleven monks. In the 1260s, the monks received a large piece of land on the outskirts of the city, initially outside the city walls, on the edge of the path leading to the port. In the mid-13th century, the coastline and port were much closer to the city, which had a beneficial effect on the economic development of the monastery, which acted as an intermediary in the trade of fish and other goods imported by sea. Also important were the monks’ connections with the Brotherhood of Blackheads from Tallinn, which made material donations to the friary, for which the monks in turn patronized the members of the community. Thanks to its favorable location and support, the friary was able to develop quickly.

The construction of stone monastery buildings and the church began around the 60s of the 13th century. At the end of the thirteenth century, the church and at least part of the eastern wing of the enclosure were probably completed. Serious construction work in the church and enclosure also took place at the end of the 14th and early 15th centuries. Around 1500, a new refectory was created in the north wing and the cloisters were rebuilt. At the beginning of the 16th century, the monastery complex obtained its final, full appearance, although construction works mentioned in the sources in the 1520s are also known, i.e. immediately before the Reformation and the end of the monastery.

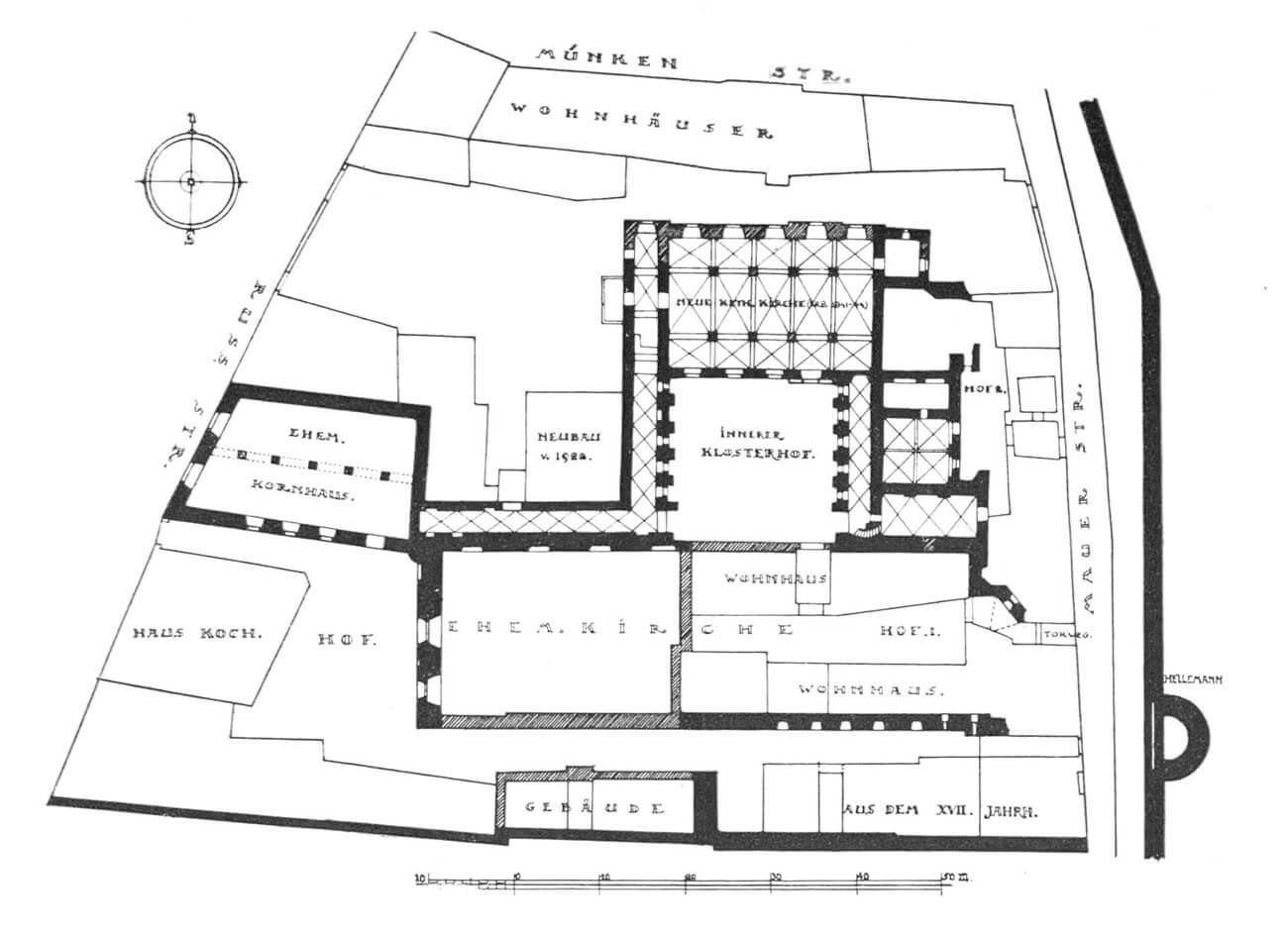

The monastery was destroyed during the Reformation in 1524, when a raging crowd invaded the church and forced the monks to leave the city. The property of the order and the monastery was considered as a property of the city. Unfortunately, as a result of a fire in 1531, the church and part of the eastern and northern buildings were damaged. Since then, they have been inhabited by the poor and the homeless. Partial demolitions, mainly of the northern wing of the monastery, took place in 1841 due to the construction of a new, nearby church of St. Peter and Paul. Also in the nineteenth century, most of the walls of the neglected and dilapidated church collapsed. In 1920, the rooms of the former western wing were demolished, and it was only in the 1950s and 1960s that archaeological research and conservation work began in the monastery.

Architecture

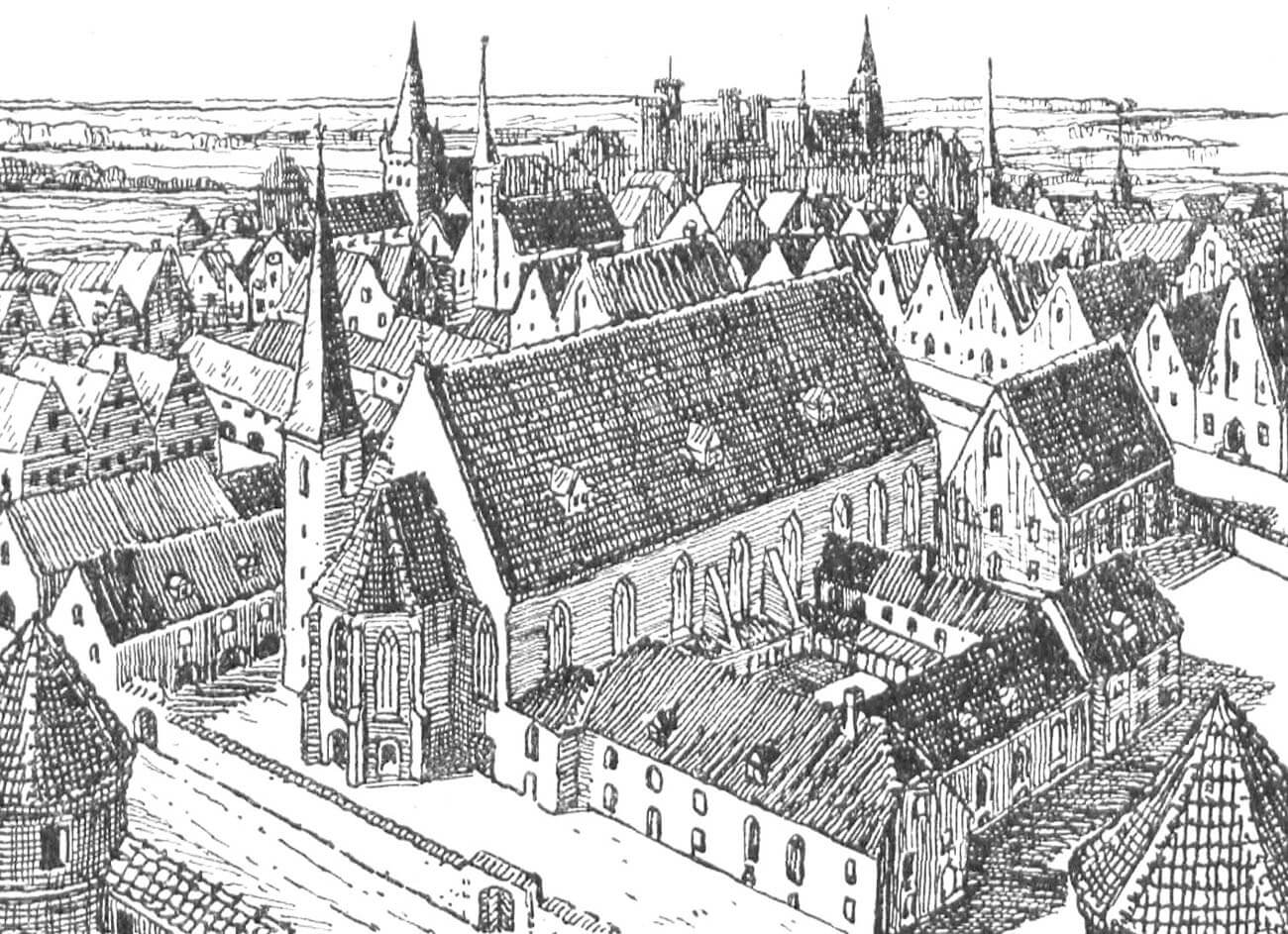

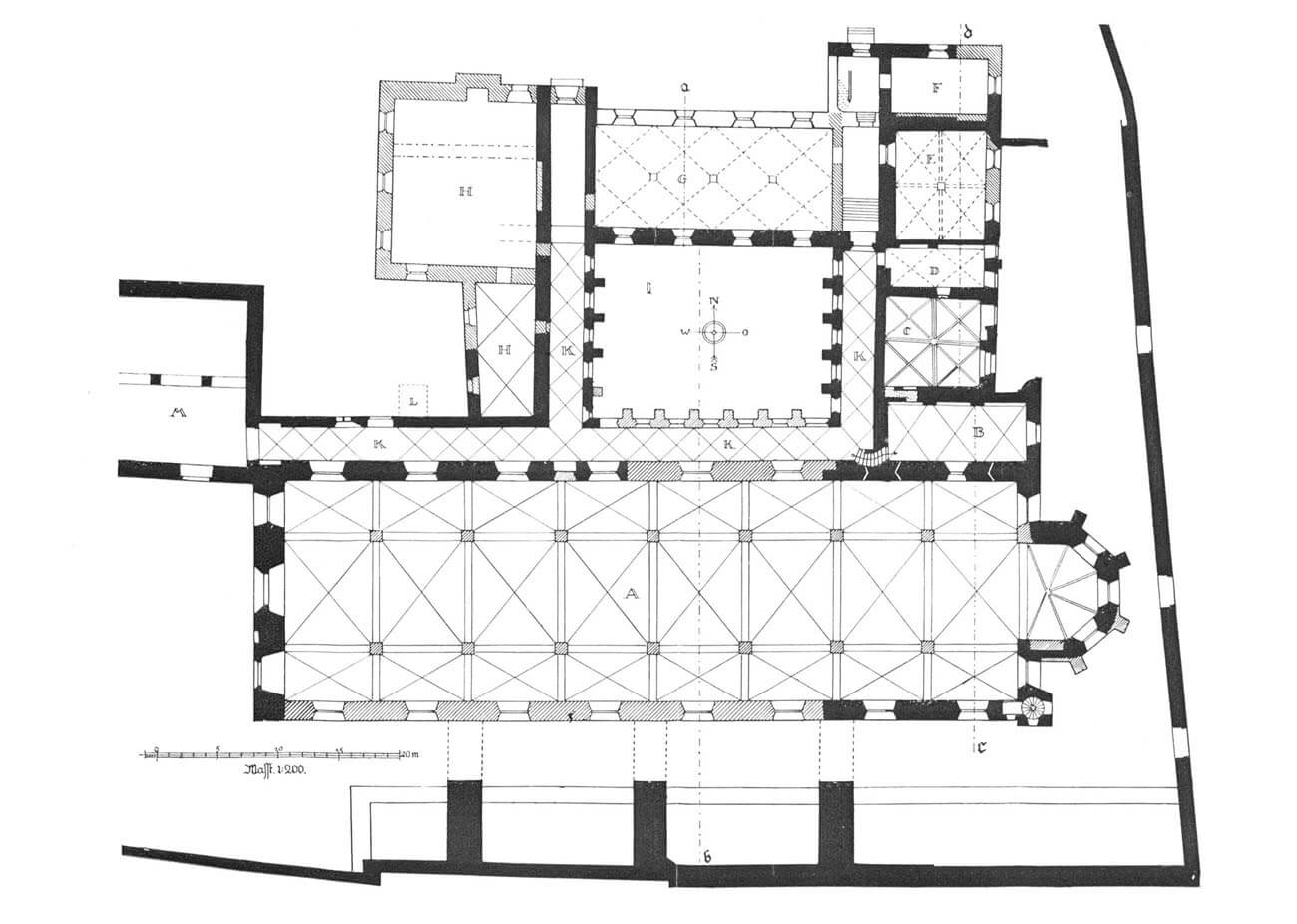

The friary was founded in the eastern part of the medieval city, so it was adjacent on three sides to narrow streets and residential plots, and on the fourth eastern side to the defensive walls, in the section between the Helleman and Behind the Monks towers. The main part of the monastery was the church of St. Catherine, located in the southern part. A small, surrounded by cloisters courtyard on a rectangular plan adjacent to it from the north. There were three wings of the claustrum next to the courtyard, moreover, there were additional economic buildings next to the walls from the north and south and in the western part of the monastery (there was a granary building adjacent to the corner of the church, unusually connected with a cloister, there must also have been stables, brewery and various types of warehouses nearby, it is also known that there was a school on the monastery grounds).

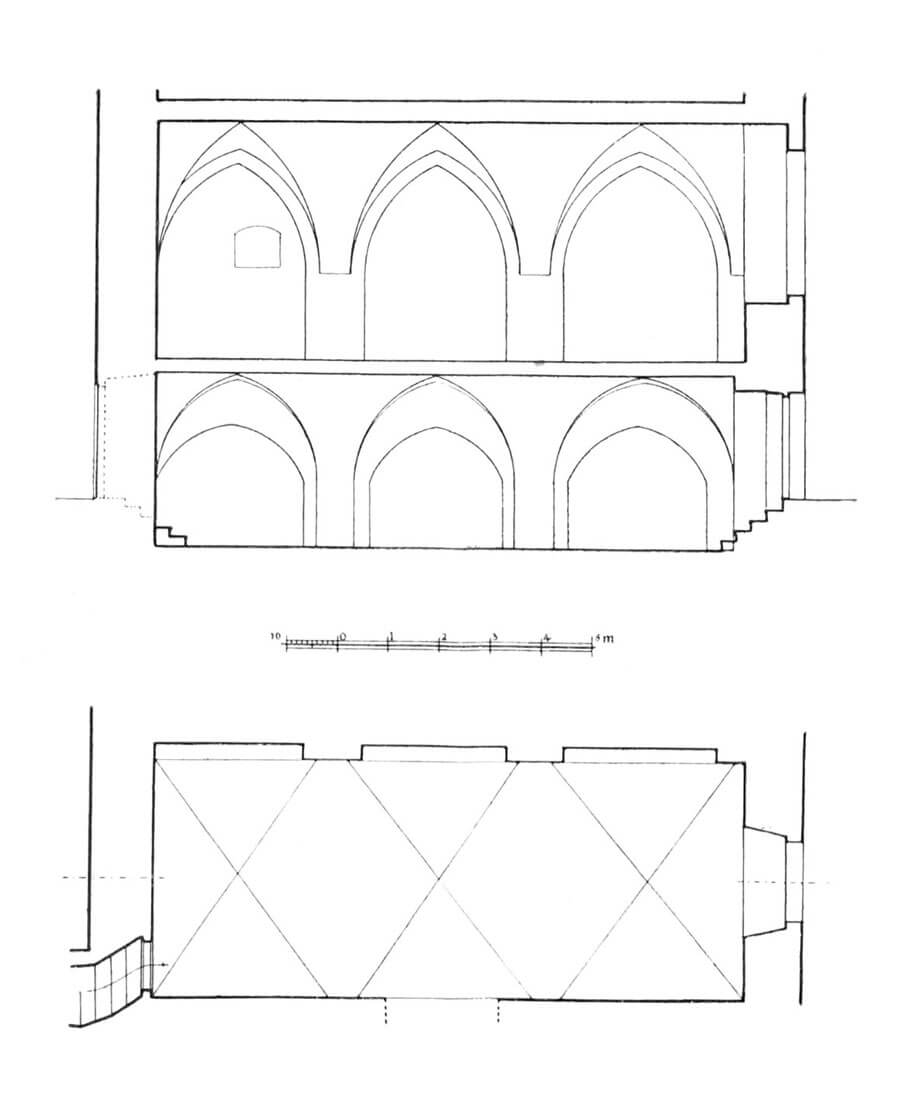

The church was impressive, although with a relatively simple layout. It was one of the largest buildings in medieval Tallinn. Its total length was 67.7 meters, width 18.5 meters, and the area was 1,219 square meters. Ultimately, at the end of the Middle Ages, it had the form of a three-aisle building in a hall system, eight bays long, with a single bay of a five-sided closure in the east, on the extension of the central aisle, protruding as a polygonal apse. On the south-eastern side, in the corner of the building, there was a slender turret that serves as a belfry and a staircase. From the outside, the church had simple facades, only the apse was supported by buttresses. The side aisles and indirectly the central aisle were illuminated by large ogival windows with tracery, partly decorated with colorful stained glass. The distances between the windows were the same, apart from minor deviations typical of medieval buildings. The entrance portals had decorative forms, especially the pointed, stepped western portal with a moulded archivolt and strips of friezes in the zone of capitals (on the left bas-relief vine leaves, on the right oak leaves with acorns).

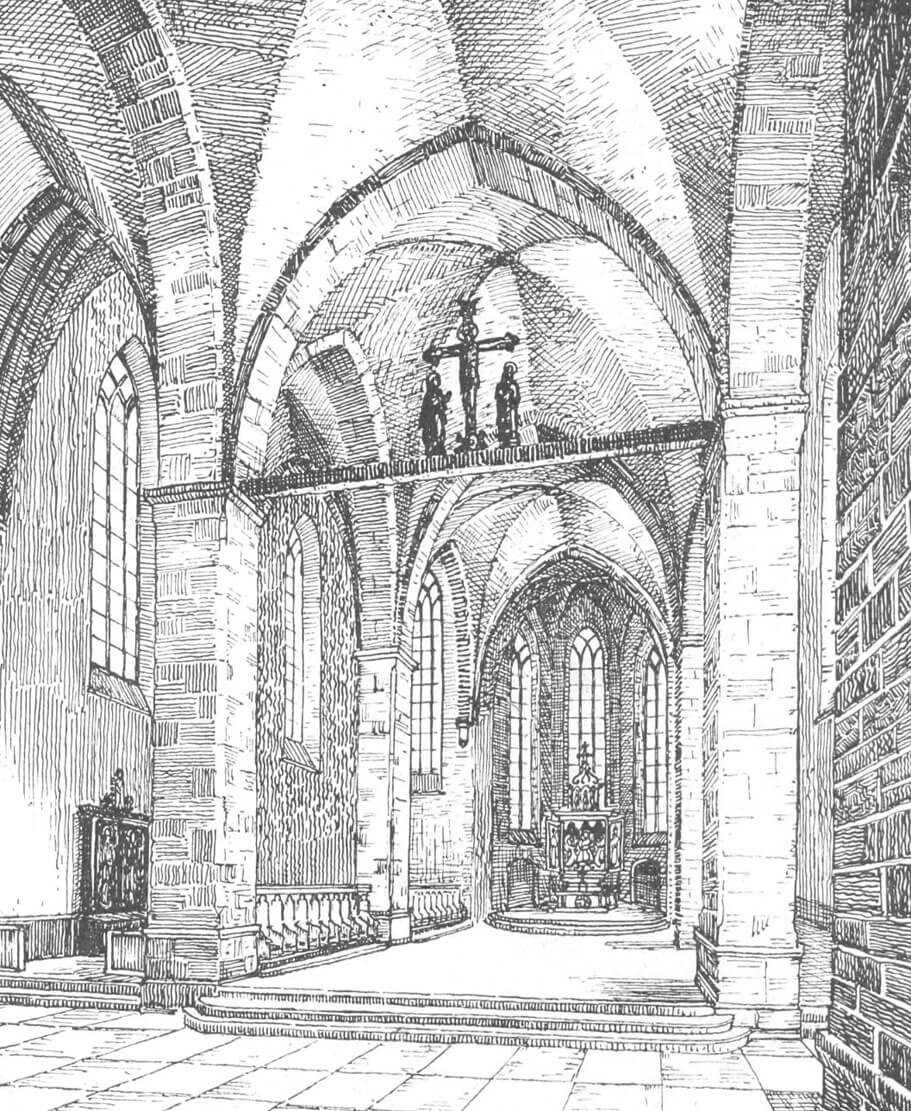

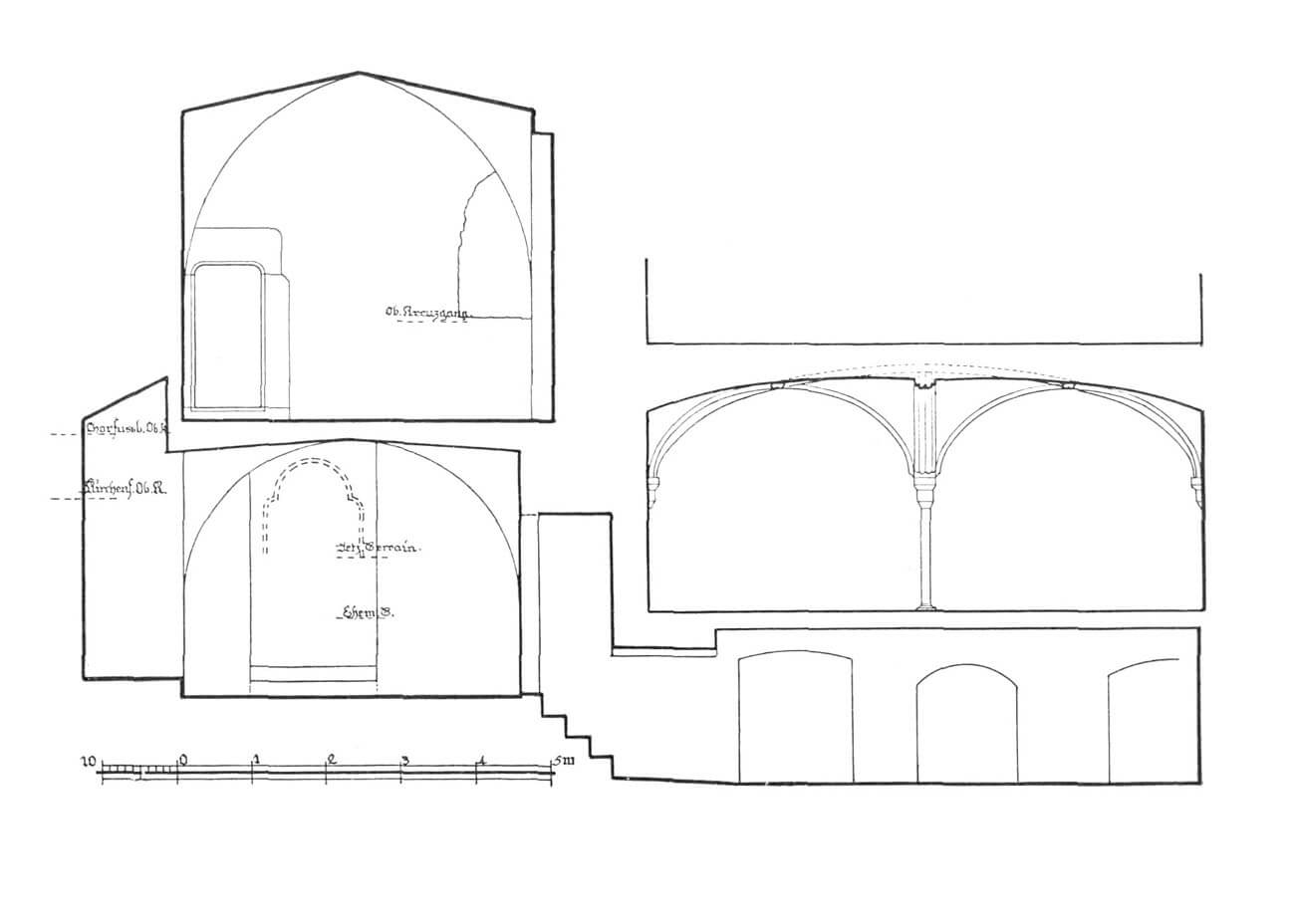

The interior of the church was divided into a publicly accessible nave, and choir and a presbytery used only by monks. These parts were separated by a rood screen or grate. The entire church was topped with high cross-rib vaults, with two additional ribs placed in the eastern apse to create a six-part arrangement. In addition to the apse, the church was divided in the central aisle into eight rectangular bays with longer sides placed transversely to the axis and into eight rectangular bays in each side aisle, where the longitudinal axes were parallel to the axis of the church. According to the construction principles of the Gothic period, the axes of the pillars and the axes of the vaults corresponded to the axes of the windows of the longitudinal walls. Under the choir there was a vaulted crypt with four aisles and six bays, part of which was used by monks, and part of it in the 15th/16th century was used by the city council, which stored cannons there. The church’s decoration was enriched by numerous altars (at the peak of church development there were about fifteen of them), funded by townspeople and municipal guilds. The facades and architectural details were decorated with colorful paintings.

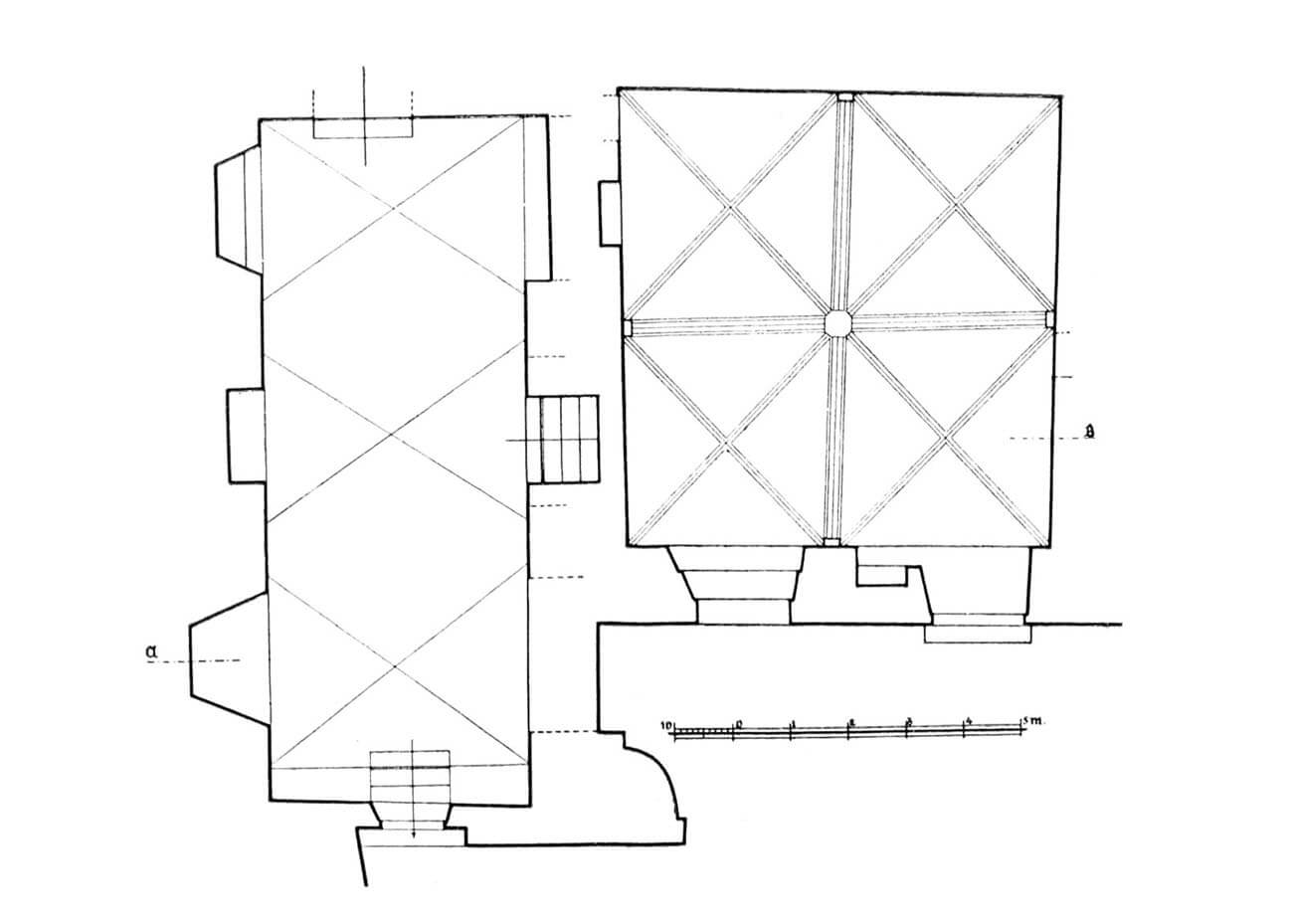

The monastery buildings located north of the church surrounded a four-sided garth with three wings and cloisters. The cloisters were reinforced from the outside with buttresses, between which high pointed windows with two-light tracery were placed, unique among the openings created in cloisters. At least in part of the layout, the cloisters were two-story and covered with a cross-rib vault. They provided access to all the most important rooms and the church, without the need to go out in the cold and inclement weather. Particularly important was the connection of the dormitory in the eastern wing with the church via the second floor of the cloister, thanks to which the brothers could quickly go to night and morning prayers. In the monastery courtyard there was a well supplying the friary with drinking and utility water and a small garden. (after the dissolution of the Dominican friary, the city moved its arsenal to the courtyard).

The most important of the enclosure buildings was the eastern wing, with a basement and a two floors, housing the most important rooms of the monastery. From the side of the church, there was a sacristy, and then a chapter house with a square plan with a vault based on a central pillar. Behind it there was a narrow room, later used as a library, and in the corner a large hall of the old refectory. On the first floor there was a brothers’ dormitory, which was probably divided into small cells with light partition walls. The head of the monastery probably had a separate, larger room, as did some of the more important brothers. In the northern wing there was the so-called a new refectory, more solemn and more spacious than the old one. It was a two-aisle hall with a length of four bays, covered with a vault supported by three pillars. Most of the two-story west wing was filled with the lay brothers’ room. Probably there was also a monastery kitchen and other utility rooms. On the west side, the monastery granary was in contact with the church building.

Current state

A part of the inner courtyard and the monastery buildings and cloisters surrounding it from the east and west, as well as two entrance portals to the church, have survived to our times. In the east wing, all the most important rooms of the monastery have been preserved: the chapter house, the alleged library, part of the former refectory, dormitory and sacristy. The northern wing of the monastery was unfortunately transformed into a church in the 19th century. As a result of a fire in 1531 and two collapses from the nineteenth century, of the monastery church only the foundations, a partially vaulted crypt under the choir, the lower zone of the west and south walls and partially the north wall, the lower part of the tower and part of the apse walls have been preserved. Brick-up windows are visible in the western part of the northern wall and in the eastern part of the southern wall. From the interior of the church, apart from the mentioned crypt, only the bases of the pillars, ribs of the vaults discovered during archaeological research, window tracery and fragments of stained glass have survived to this day. In total, the ruins of the friary of St. Catherine’s are one of the best-preserved urban monastic complexes throughout Livonia, and at the same time the only partially preserved mendicant friary in Estonia.

bibliography:

Alttoa K., Bergholde-Wolf A., Dirveiks I., Grosmane E., Herrmann C., Kadakas V., Ose I., Randla A., Mittelalterlichen Baukunst in Livland (Estland und Lettland). Die Architektur einer historischen Grenzregion im Nordosten Europas, Berlin 2017.

Kühnert E., Das Dominikanerkloster zu Reval, Reval 1926.