History

The Bridgetite nunnery with the church of St. Bridget was founded in 1407. The complex was established with the support of the Teutonic Order, but mainly thanks to the foundation of three wealthy merchants: Hinrich Huxer, Gerlich Kruse and Hinrich Swalbart, some of whom later became monks. Also in the foundation was involved the Swedish convent from the Vadstena, which in 1410 sent a delegation to the bishop of Tallinn and master of the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order to petition Pope John XXIII for confirmation of the foundation and privileges of the monastery, officially named Vallis Mariae, which happened in the year later.

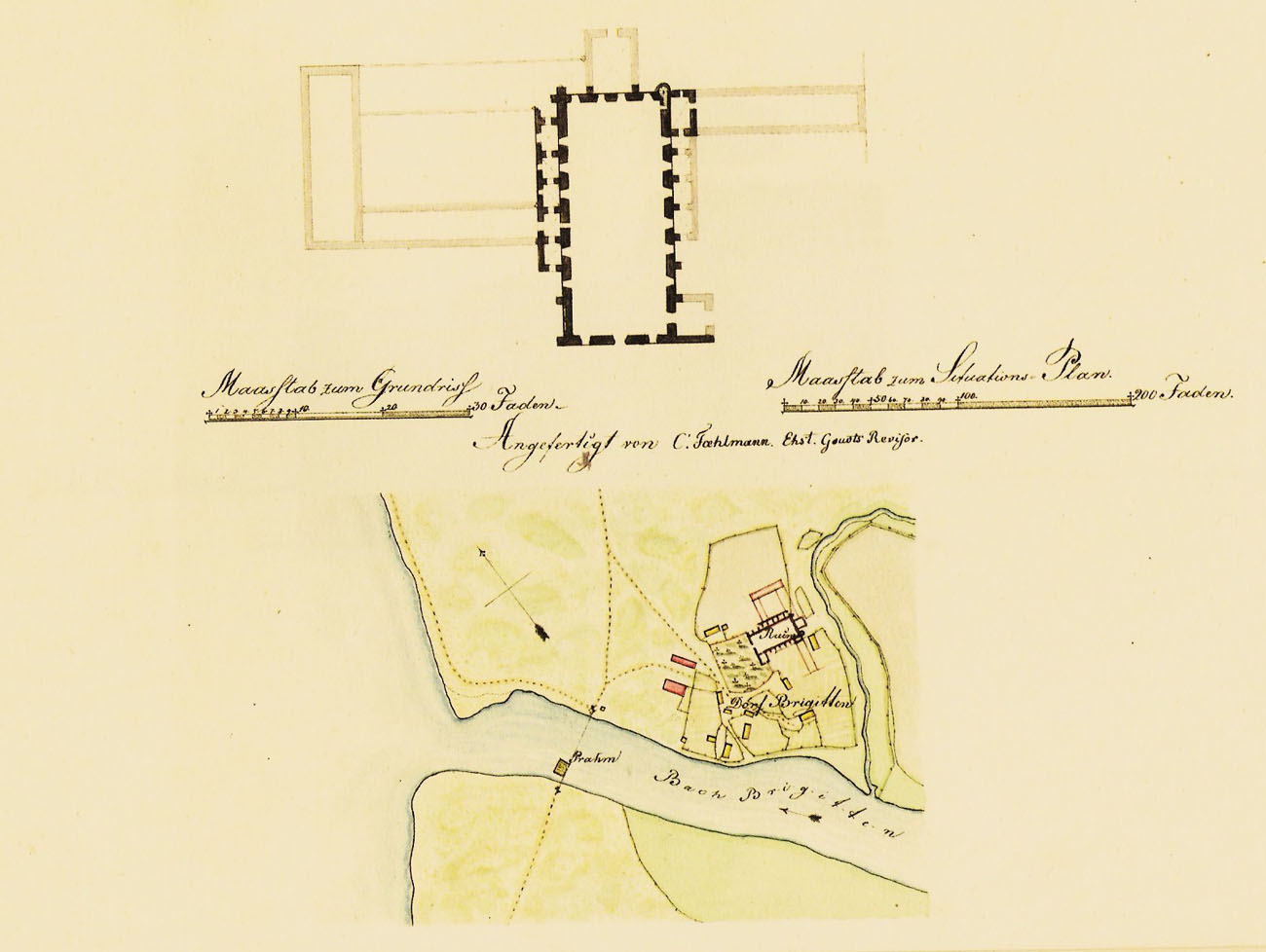

Initially, the monastery buildings were wooden, while the construction of stone ones began in 1417, after obtaining permission to use the quarry, five years after the arrival of the first sisters from the mother congregation. The delay in the commencement of construction works was related to a conflict with the Tallinn municipality, which was trying to move the convent into the interior of the country. When the dispute was settled by the final decision of the Grand Master in 1416, construction work was already carried out efficiently and the monastery church was consecrated in 1436 by Bishop Heinrich II. The extension of the monastery took place at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, when a large chapel was added in the south-eastern corner of the church and a hexagonal chapel in front of the church. Both men and women lived in the completed monastery, located in screen-off buildings and sitting in various places in the church. The monastery was the largest convent in Livonia, there were up to 85 brothers and sisters in it.

The fall of the monastery began in 1525 due to the progress of the Reformation, although it was allowed to continue functioning. In 1564, a great fire broke out in the monastery, and in 1575, during the Livonian War, it was attacked by the troops of Ivan the Terrible, which plundered and set fire to the monastery’s buildings. Since then, it has been in ruins. Although it was abandoned, it was used by local citizens for a long time as a cemetery, and some of the monastery rooms were used until the beginning of the 18th century.

Architecture

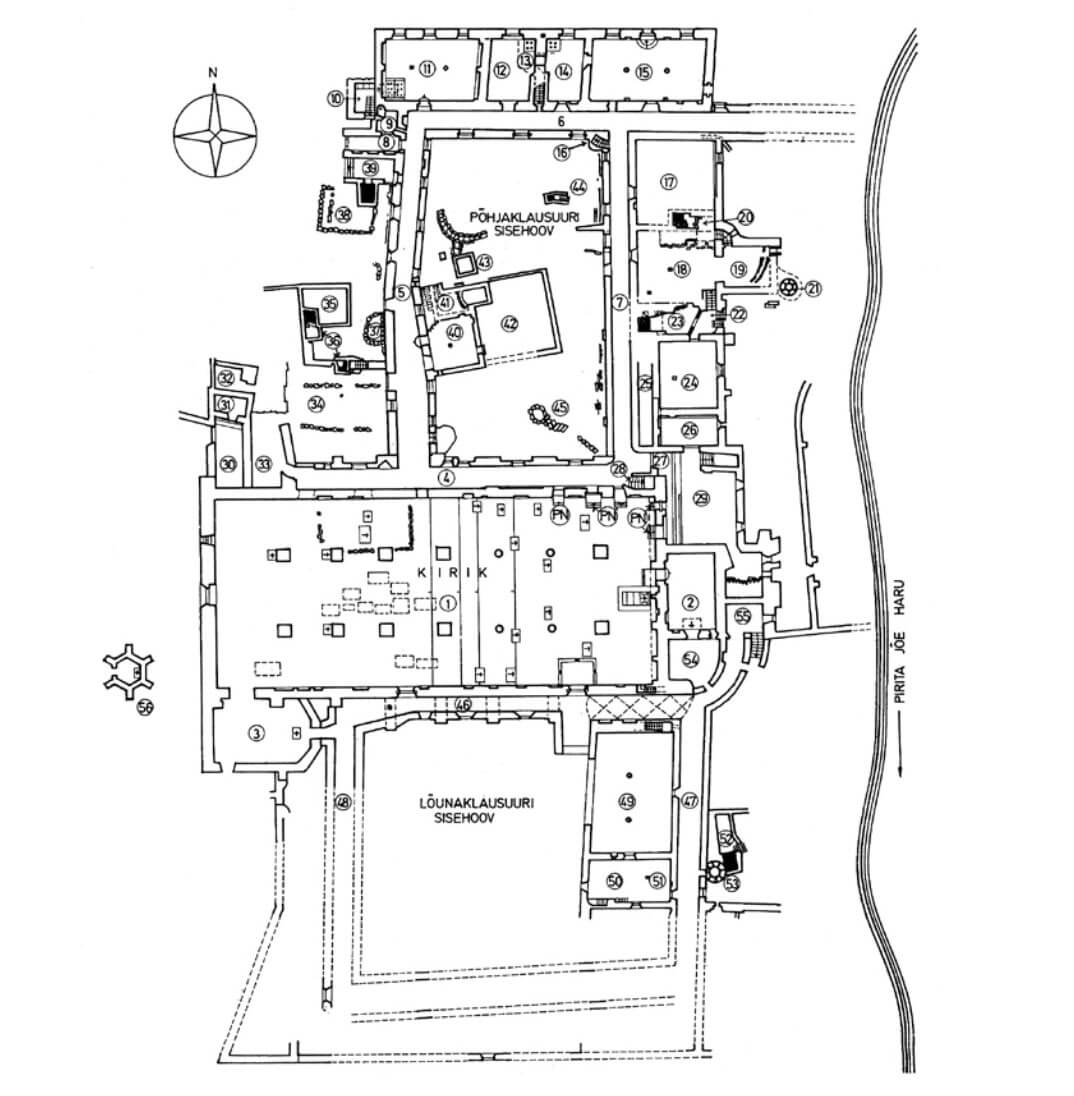

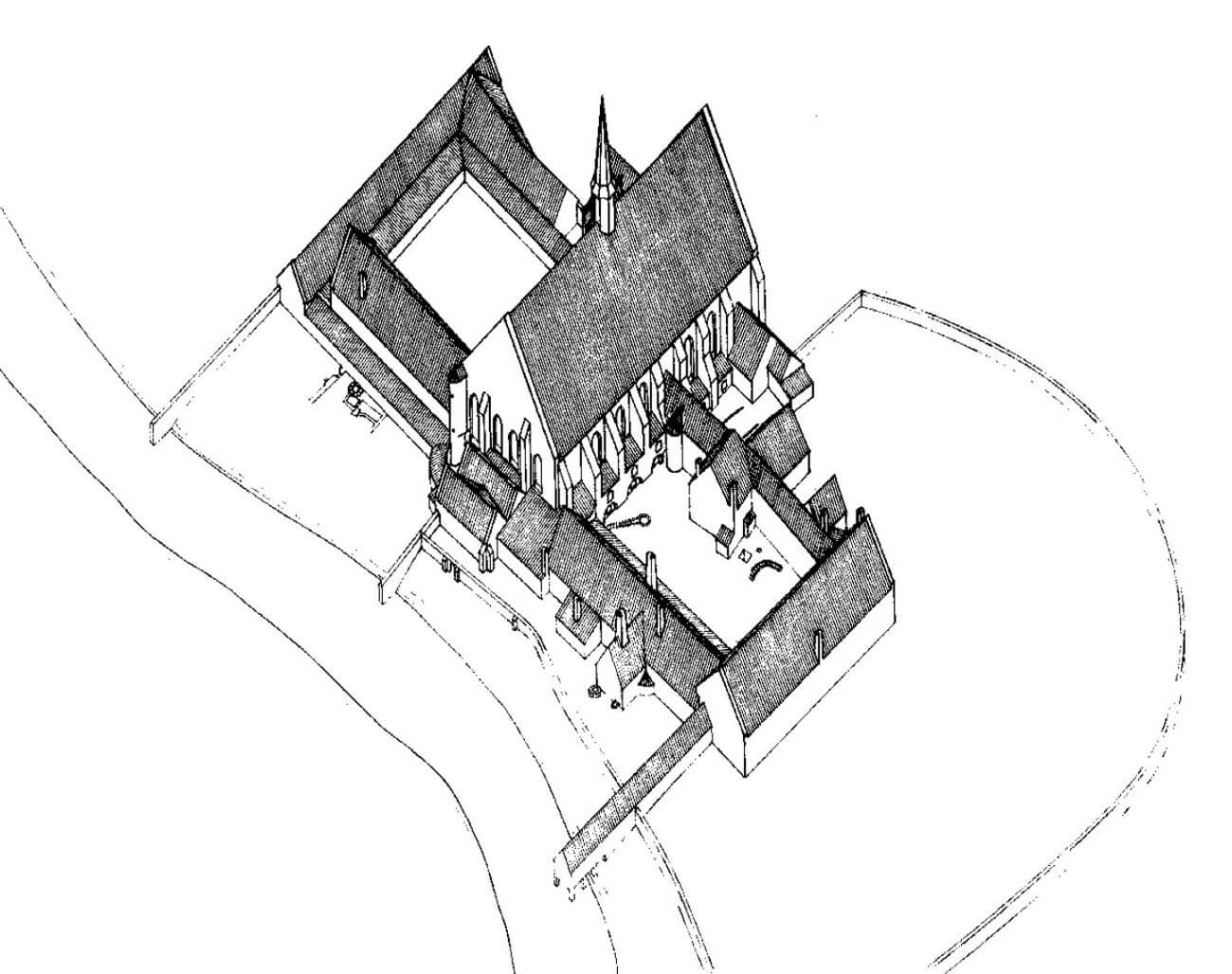

The monastery was established outside the city walls, east of the medieval city, on the road from Tallinn to Narva, on a large plot of land bordered by the Birgitten Bach (Pirita) river from the south and a smaller stream flowing into it from the east. The core of the complex was a magnificent monastery church, adjacent to the south and north with the enclosure buildings: the first for the brothers and the second one for the sisters. There were also numerous additional buildings, mostly of an economic nature, scattered nearby, and a hospital (infirmary) located at a certain distance in the north-eastern part of the monastery complex. On the west side of the church, a more unique structure was erected, a free-standing, hexagonal chapel with buttresses at the corners.

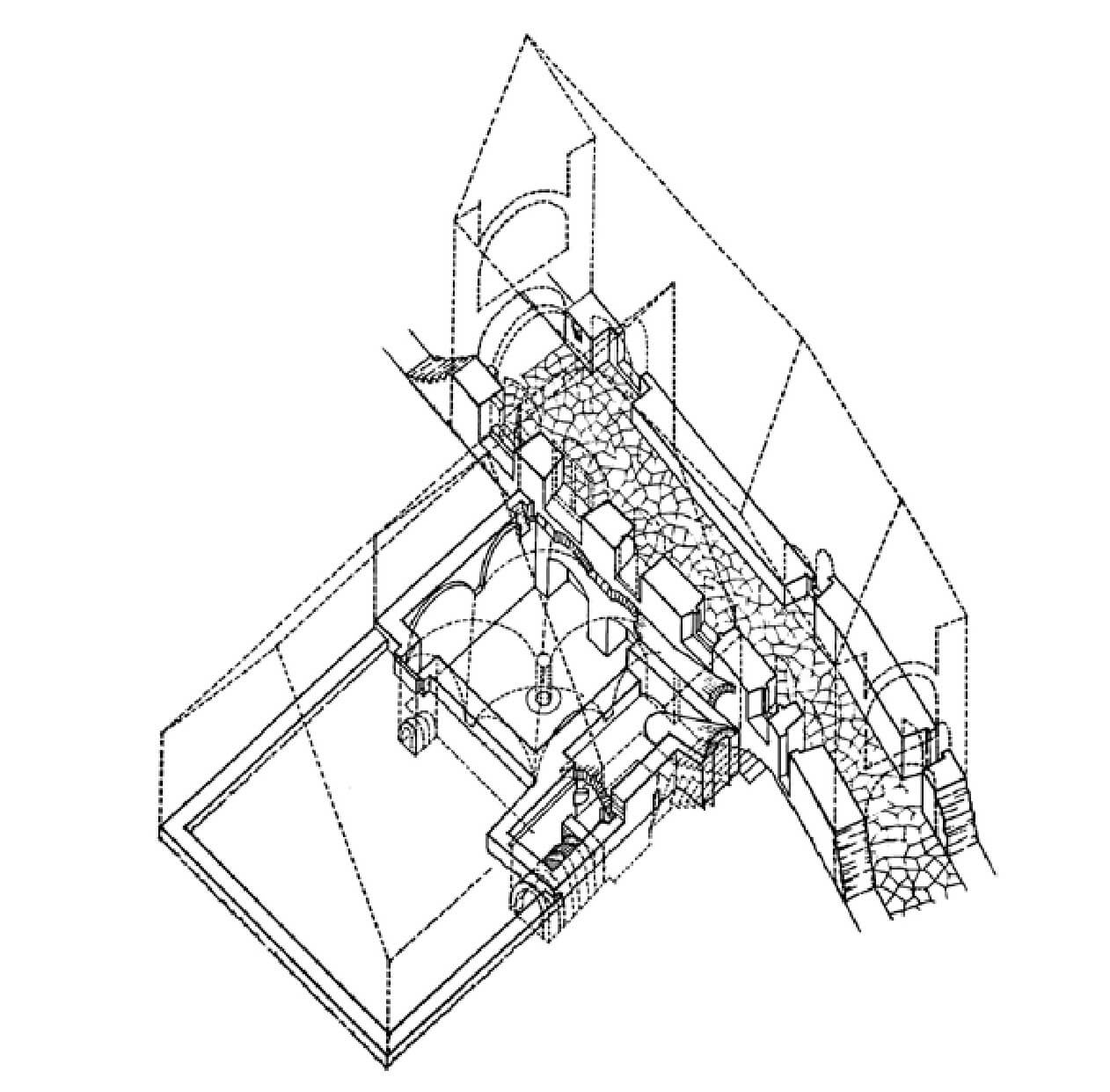

The monastery church was a spacious hall-type structure (although originally planned as a basilica, as evidenced by low corbels), with central nave and two aisles, eight-bay, rectangular in size, 24 × 56 meters, with massive, double-step buttresses reinforcing each 20-meter high wall from the outside. Additionally, in the south-west corner, the chapel of St. Michael was built, which was an aisleless building with a three-sided ending in the east.

There were very specific building regulations in the Brigitte sisters churches, which were only partially implemented near Tallinn. The church had to face the altar west instead of traditionally east, but here the choir area was orientated east, and the main entrance to the church was traditionally to the west. This, of course, was for practical reasons, as the road ran west of the church and the church bordered a stream to the east. Therefore, the most decorative appearance was obtained by the western facade of the temple, decorated with a magnificent, triangular gable with a height of 35 meters. It was separated by five tall, pointed-arched blendes, in which there were smaller ogival, cross and circular niches, as well as window openings of various shapes. Below the gable, three relatively small pointed windows, originally filled with traceries, were pierced, and on the axis a stepped entrance portal flanked by two small niches with triangular arches. Probably originally there were carved figures or lamps, or candles in it.

The longitudinal walls of the church were separated by the abovementioned buttresses, between which there were six pointed, high windows from the south and five in the north wall. A more unusual solution was the eastern wall, reinforced with two buttresses with single windows at the end of the aisles and with two windows illuminating the central nave. They were all decorated with traceries. In the south-east corner of the church, there were also spiral stairs leading to the space above the vaults, and a sacristy at the eastern wall.

Inside, the church was divided into two equal parts by a rood screen: the western part, which could be entered through a portal in the facade, was open to lay people, while the eastern part belonged only to the inhabitants of the monastery. The eastern part was also divided: the brothers sat on the ground floor of the choir, and for the nuns a large balcony – a gallery – was separated in the northern aisle. The church was characterized by a large number of wall recesses, in which at least some altars were located (at the peak period there were at least 20 of them).

To the north of the church there were the buildings of the sisters’ enclosure, surrounding with the temple and four lines of cloisters, a rectangular patio located inside. At least the southern side of the cloisters was two-story and led through openings pierced through the buttresses of the church. The largest of the buildings was the alleged abbess’ house, located very unusually in the nunnery inner courtyard. Initially, it was a stone and wood structure, as indicated by the small thickness of the walls. It had a brick basement in the northern part of which there was a hypocaustum stove, which heated the rooms on the upper floor with warm air. The basement also housed a square living room with dimensions of 5.8 x 6.1 meters, covered with four bays of a vault based on a central, hexagonal pillar, and a small entrance hall in the north-west corner, from which stone stairs with nine steps and a height of 1,8 meters led outside. In the second stage, the building was enlarged on the eastern side, where a room measuring 9.8 x 11 meters was placed. In addition, on the north side, an annex was erected with a stone, underground pit and a wooden above-ground part serving as a latrine. The entrance to it was from the west, from the cloister.

Of the three wings of the sister’s claustrum, the western part had the most loose buildings, perhaps originally partly built of a wood. The eastern wing, on the other hand, stretched out beyond the church, where there was only direct connection to the male part of the monastery. This parlour was divided by partitions, and communication was possible only through special windows. In addition, in the east wing there were utility rooms, a monastery kitchen and a sisters’ workshop, the most northerly. The northern part of the enclosure was designed most impressively, with a three-bay, two-aisle chapter hall heated with a hypocaustum stove, two smaller heated refectories and a large, though unheated, refectory for guests. All these rooms were topped with vaults. They were entered from the cloister side, only the refectory for guests had a separate entrance in the north wall, which meant that it could be entered from outside the enclosure. Since the staircases have survived, it can be assumed that the northern wing was two-story, and its upper part was occupied by the nuns’ dormitory.

To the south of the church there was a brothers’ enclosure, which could accommodate up to 25 monks (for comparison, the northern enclosure was supposedly intended for as many as 60 sisters). At least on three sides (from the west, north and east), and perhaps from each side, the courtyard was surrounded by cloisters, while their eastern part was led in a very unusual way on the outside of the buildings, right above the stream. This allowed for a better connection with the parlour behind the chancel of the church. The northern cloister was built as a passage through the buttresses supporting the vaults of the church, but unlike the corresponding nuns’ cloister, this one was one-story. The eastern wing of the brothers’ buildings was two-story. From the north, in the lower part there was a spacious, two-aisle, three-bay refectory, heated with a hypocaustum stove. A smaller room to the south of the refectory was intended for serving meals, as there is a service hole in the wall between them. This indicates a location near the kitchen as well, but the exact layout of this part of the monastery remains unknown.

Current state

To this day, the monastery church has survived, in the form of a very well-preserved ruin with all the walls, and only without internal pillars and roofs. Of the remaining monastic buildings, only the foundations, some of the cloisters and cellar rooms have remained. The monastery (est. Pirita Klooster) is open to visitors, there are also numerous outdoor events, including Bridget Festival, a concert of classical and sacred music.

bibliography:

Alttoa K., Bergholde-Wolf A., Dirveiks I., Grosmane E., Herrmann C., Kadakas V., Ose J., Randla A., Mittelalterlichen Baukunst in Livland (Estland und Lettland). Die Architektur einer historischen Grenzregion im Nordosten Europas, Berlin 2017.

Rajamaa R., Pirita kloostri asutamine ja üles- ehitamine 1407–1436 Rootsi allikate valguses, “Kunstiteaduslikke Uurimusi”, 16 (4), 2007.

Tamm J., Residences of abbesses in Estonian monastic architecture, based on the examples of St Michael’s Cistercian convent in Tallinn and the Brigittine convent in Pirita, „Baltic Journal of Art History”, vol. 2 (2010).