History

After the conquest of the surrounding lands by the Crusaders in the mid-13th century, the area around Padise was given to Cistercian monks from the abbey in Dünamünde (Daugavgrīva). Shortly afterwards, they built a small chapel there, recorded in documents in 1281. In 1310, after the Teutonic Order had purchased the native monastery in Dünamünde five years earlier and turned it into a commandry, the Cistercian community moved to Padise. In 1317, King Eric VI Menved of Denmark gave permission for the monks to build a full-fledged stone monastery in a new place.

In 1343, on Saint’s George Eve, the abbey in Padise was captured and burned by Estonian insurgents, and 28 monks were killed. After the Teutonic Knights purchased the surrounding areas from Denmark, they allowed the local monks to rebuild the monastery. Construction works were carried out in the second half of the 14th century, with the greatest intensity probably at the end of that century. From that moment on, the importance and wealth of the Cistercians of Padise continued to grow. Already at the beginning of the 15th century, the commandry owned numerous lands not only in Livonia, but also in Swedish Finland. In 1448, the consecration of the monastery church by the bishop of Tallinn was recorded, which may have been related to the completion of renovation and construction works at that time. In the late 15th century, the construction of the southern and eastern wings was probably completed, and buildings in the western courtyard were created.

In the 16th century, the Reformation did not significantly affect the functioning of the monastery. Only in 1558, appreciating the military values of the building, the last Teutonic Master of Livonia, Gotthard Kettler, captured the abbey and expelled the monks. Already in 1561, Padise was occupied by the Swedes, and a year later Kettler threw off his monastic habit and placed himself under the protection of Poland and Lithuania as a Protestant prince. In 1576, the abbey was captured by Moscow. The Swedes regained it in 1580 after a long siege and devastating bombardment, and then transformed it into a royal court. In 1622, King Gustav II Adolf handed the building to the burgrave of Riga, Thomas Ramm, whose heirs owned Padise until 1919. On the premises of the former monastery, they arranged utility and residential rooms for the manor, and demolished some of them in order to obtain building materials. At the end of the 18th century, the buildings were abandoned and fell into ruin.

Architecture

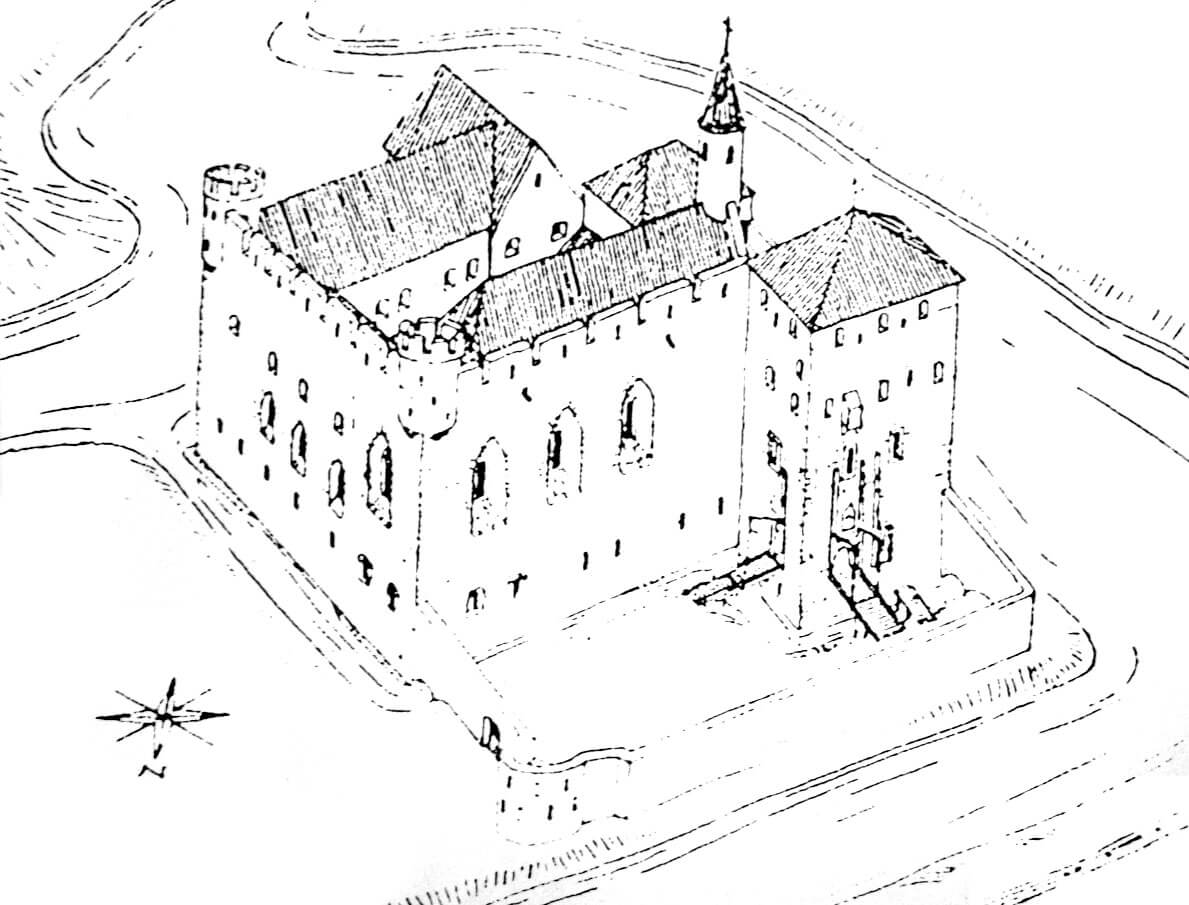

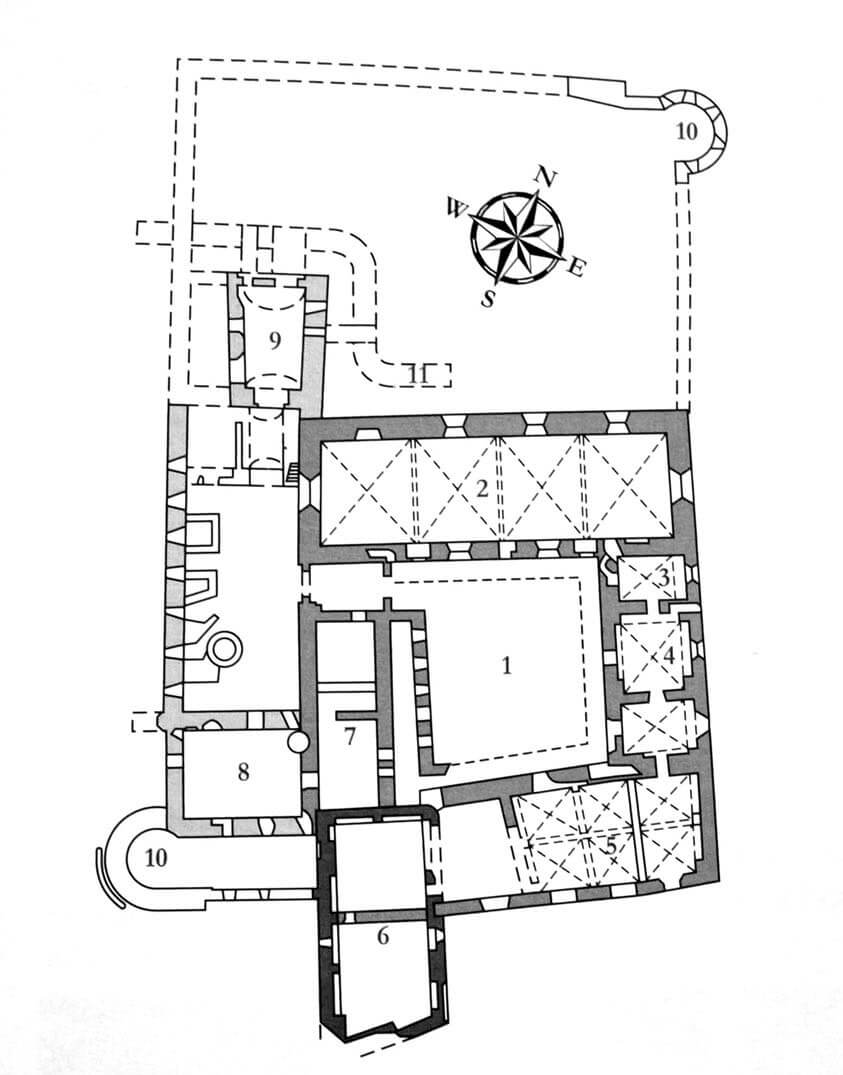

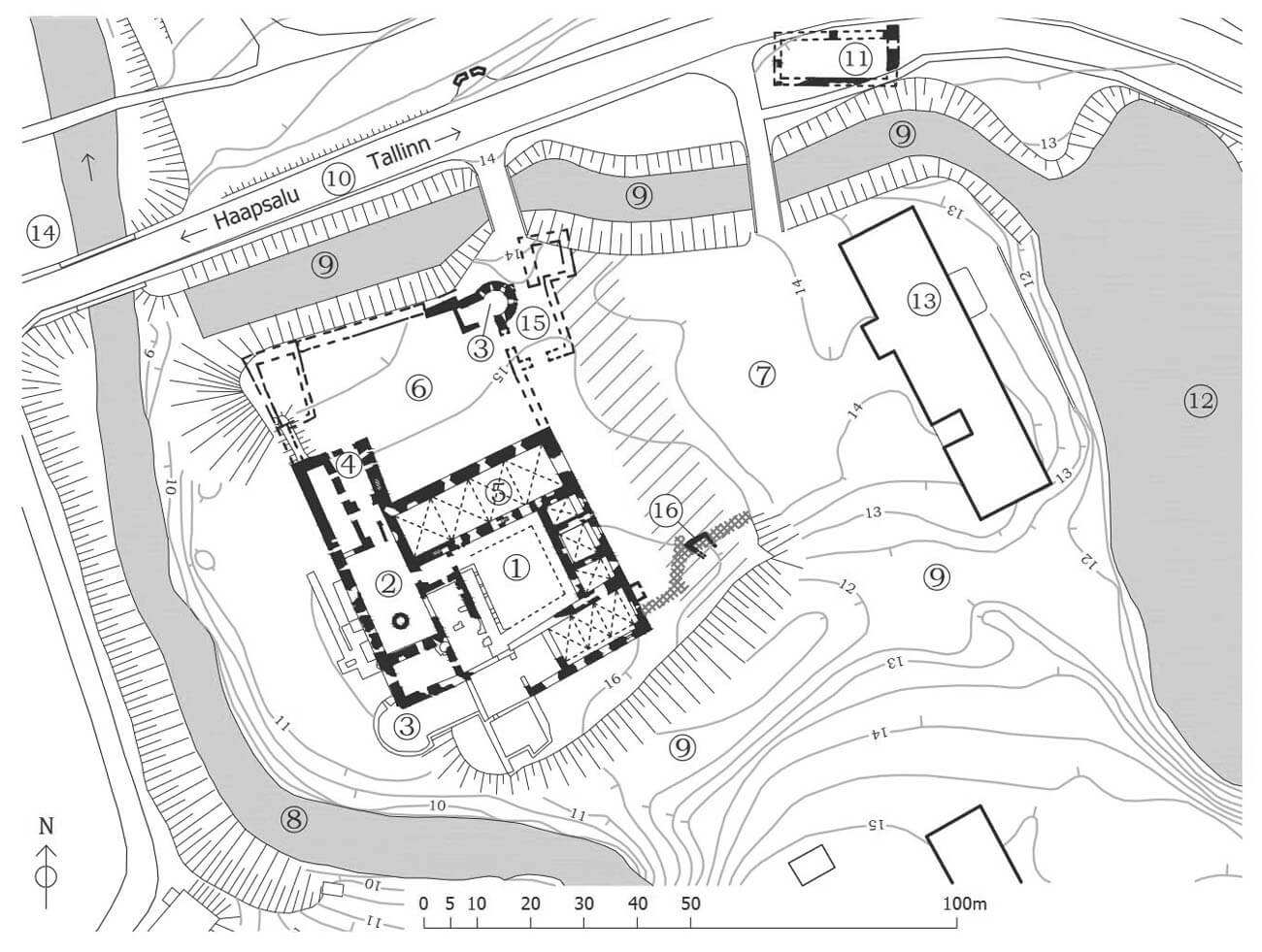

The abbey in Padise in the 15th century consisted of a four-bay church without an externally separated chancel, the claustrum buildings located south of it, surrounding a trapezoidal garth with cloisters, as well as a small western courtyard and a defensive wall separating another northern courtyard. On the eastern side of the claustrum there was the most extensive courtyard with an economic function. The whole was located in the bend of a small river flowing on the western and partly southern sides, which was used to irrigate the approximately 15-meter-wide moat and create a pond on the eastern side. The moat connected the river with the pond on the northern side of the complex, and also separated the claustrum from the eastern courtyard and secured the entire complex from the south. Outside the moat, on the north-eastern side, there was a late Gothic chapel.

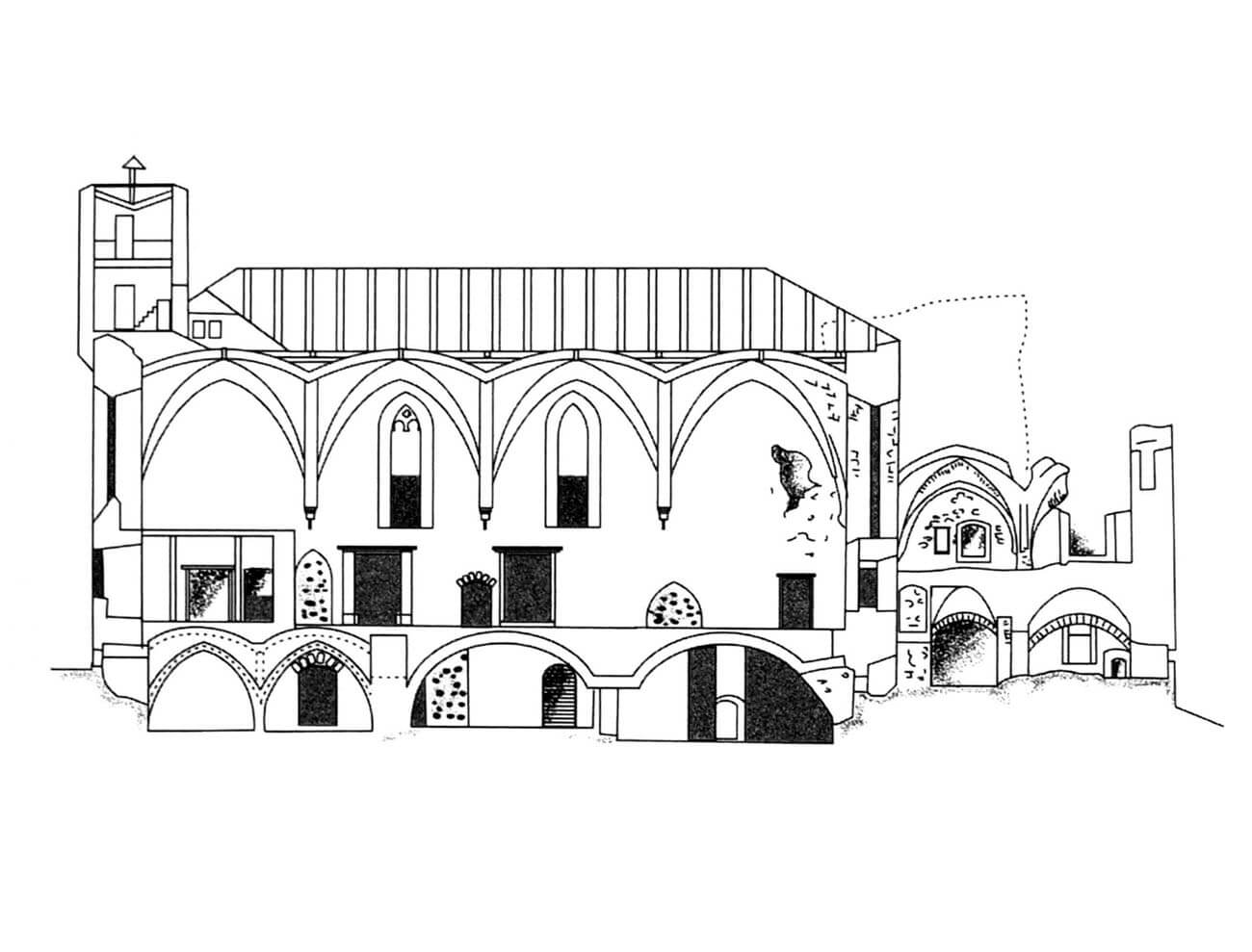

The nave of the monastery church, as the weakest elements of the defense, was raised several meters above the ground level, and a spacious, windowless ground floor was constructed beneath it, the so-called lower church. Unlike the Falkenau monastery church, in Padise the lower floor occupied only the eastern part of the building, constituting a square crypt with a vault supported by a central pillar. The more spacious upper level of the church was equipped with large, pointed windows and topped with a cross-rib vault, divided into four nearly square bays. As the Cistercian rule prohibited the construction of church towers, only a small turret was built on the temple, and the church did not have any clear height dominant elements over the compact enclosure buildings.

The entire complex of claustrum was strongly fortified, because in addition to the external fortifications, individual wings and towers were topped with wall-walks protected by battlemented parapets. Moreover, the two eastern corners were topped with rounded bartizans, mounted on squinches above the church and the southern wing. From the south-west corner, in front of the compact quadrilateral claustrum, there was an avant-corps, which was an older building from the 13th century incorporated into the abbey. In the 15th century, a narrow courtyard with a well was created on the western side of the claustrum, enclosed from the south by a tower-like building and from the north by a gate tower. Additionally, in the 16th century, low semicircular towers were built in the corner of the northern courtyard and on the southwestern side of the claustrum.

In all three wings of the claustrum the main rooms were created on the second floor, a few meters above ground level, above the ground floor partially sunk into the ground. Communication between these levels was provided by cloisters, while staircases led to the third, highest floor, located above all wings. The eastern wing of the monastery on the main floor was occupied by three rooms: a sacristy in the north, a chapter house in the middle and perhaps a parlour in the south. Above, there was probably a dormitory room, directly connected to the church to enable the monks to quickly go to night and morning services. Most of the southern wing was filled by a three-bay refectory, while the western wing contained utility and residential rooms intended for lay brothers. Both wings were connected in the corner by a chapel, located in the oldest part of the abbey.

The entrance to the compact, strictly closed complex of the claustrum was located next to the church in the western wing. Unusually, it was closed with a portcullis. When, in the 15th century, the above-mentioned four-sided gate tower was added on the north-west side, adjoining the church in one of its corners, it housed a system of drawbridges, spanning on both sides over a ditch dug in the northern courtyard. In the northern wall of the tower there were two drawbridges, one for pedestrians and one for carriages. The third drawbridge was placed in the eastern wall of the tower. It probably served to provide pedestrian access to the cemetery, which was separated from the northern courtyard by some form of fence. The northern courtyard was accessed by a gate complex in the north-eastern corner, consisting of a gatehouse protruding towards the northern moat and a building sandwiched between the northern courtyard and the moat in front of the eastern courtyard.

Current state

The monastery complex in Padise is the best preserved medieval, fortified monastery in the area of Livonia. It is also a very interesting example of the sacraland defensive architecture of a religious order, other than the Teutonic Knights. The entire north-eastern part of the monastery has been preserved with the most important rooms: a chapter house, a sacristy, and above all a church with underground with Gothic vaults. Unfortunately, the south-western part was destroyed during the Livonian War. The ruined parts of the corner quadrilateral tower, gate tower, western and southern wings and the walls of the western courtyard are subject to gradual revitalization works.

bibliography:

Borowski T., Miasta, zamki i klasztory. Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Kadakas V., Archaeological studies in Padise monastery, „Archeological fieldwork in Estonia 2011”, Tallinn 2012.

Kadakas V., Ööbik P., Reppo M., Archaeological studies in the Cistercian monastic complex in Padise, „Archeological fieldwork in Estonia 2019”, Tallinn 2020.

Tuulse A., Die Burgen in Estland und Lettland, Dorpat 1942.