History

In 1245, the division of the Livonian possessions was completed, conquered in the last phase of the Northern Crusades. Most of the island of Saaremaa then passed into the hands of the Prince-Bishop of Ösel, while the neighboring smaller island of Muhu and the northern and eastern parts of Saaremaa passed to the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Knights Order. The management and defense of these areas was to be carried out from the castle in Peude (Pöide), which, however, was destroyed during the Estonian uprising of 1343-1345. After the suppression of the rebellion, it was decided not to rebuild Peude, but to entrust its function to Soneburg Castle, built in 1345 by the Livonian Land Master, Burchardt von Dreileben, as a new administrative center for the Teutonic estates in Ösel (Saaremaa), located directly by the sea. The defeated Aesti were forced to do the construction work, which is why the building was named “Sonenborch”, i.e. Castle of Atonement.

Master Burchardt von Dreileben did not manage to complete the castle, only in the following years his successor, Land Master Goswin von Herreke, enlarged the castle house and completed the construction process. In the 15th century, Soneburg was strengthened with fortifications and towers adapted to the use of firearms. The castle was located far from the areas of the main military conflicts that took place in the Middle Ages, so it was continuously in the hands of the Teutonic Knights until the secularization of the Order, and even slightly longer, because the German, secularized crew ruled the castle until 1562. It was then that the Danish King Frederick II took possession of Soneburg Castle, and its last bailiff, Heinrich von Ludinghausen-Wulff, received the title of “royal praetor”. Under short Danish rule, Soneburg became a border castle between Denmark and Sweden.

In 1566, the island of Saaremaa was invaded and devastated by Swedish troops, for whom it was an important bridgehead for further expansion. Unable to defend any place other than Kuressaare Castle in the event of a next Swedish attack, the Danes destroyed Soneburg later that year. However, they soon began to regret their hasty decision and rebuilt and even strengthened the castle with a north-eastern artillery bastion. But this turned out to be insufficient and in 1568 the Swedes captured Saaremaa again. The peace treaty signed in 1570 provided that Sweden would return Maasi and neighboring areas to Denmark, but John III decided not to respect the provisions and in 1575 gave the castle to Prince Magnus, allied with Sweden. He arrived on the island and imprisoned the Danish praetor Claus von Ungern. Shortly thereafter he left Saaremaa and freed Ungern, who responded by besieging Soneburg. The defenders surrendered after a few days due to a large fire that broke out in the castle. Fearing that it would be occupied again, the Danish King Frederick II ordered Soneburg to be blown up. In the early modern period, the ruins were used as a source of free building material.

Architecture

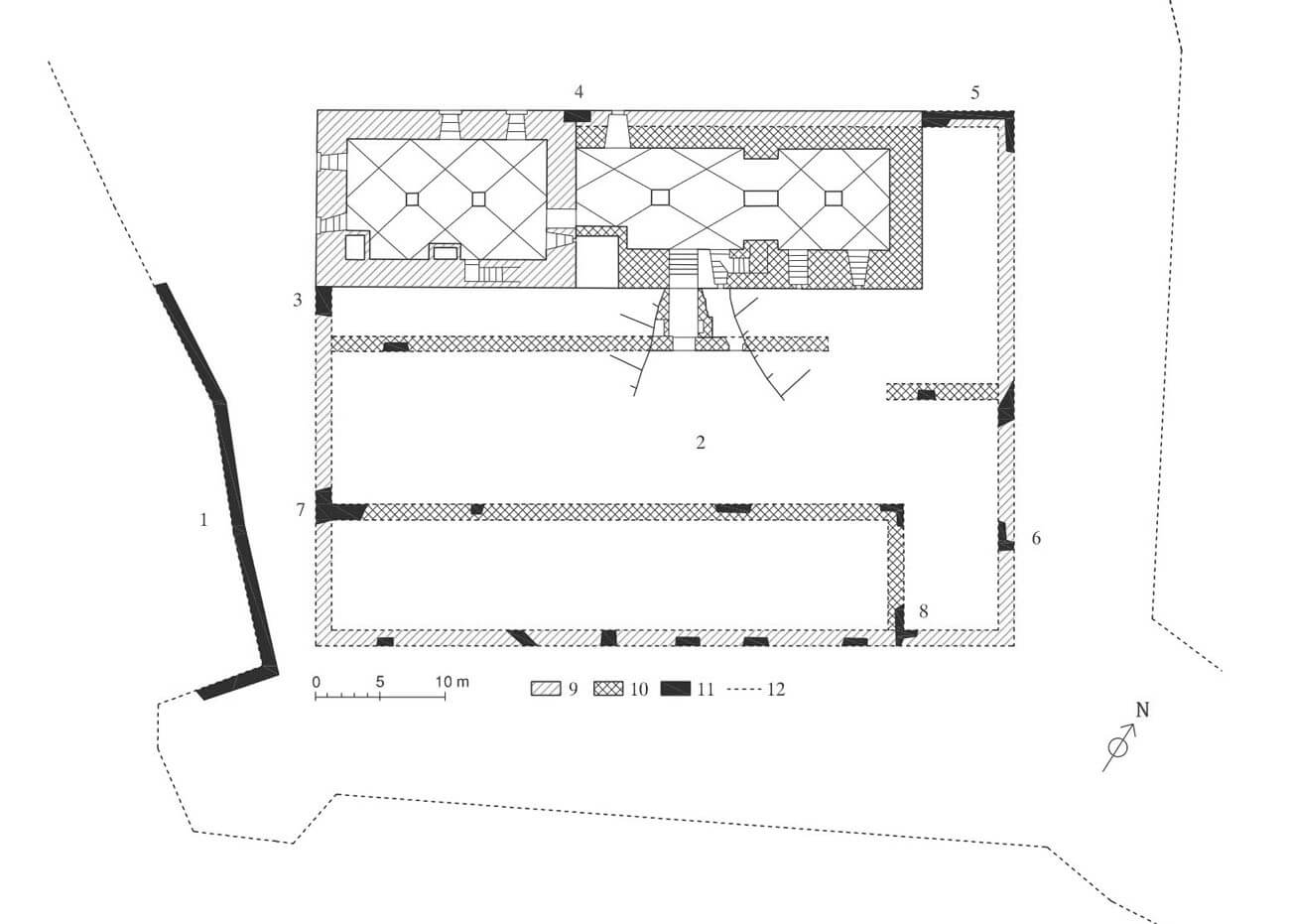

Soneburg Castle was built on the seashore, sloping gently on the northern and western sides towards a shallow bay and strait between the islands of Saaremaa and Muhu. A small settlement developed near the castle, with a boat marina nearby. The access road to Soneburg must have led from the south, where it was probably protected by earth fortifications. The castle was also adjacent to the mainland of the island on the eastern side.

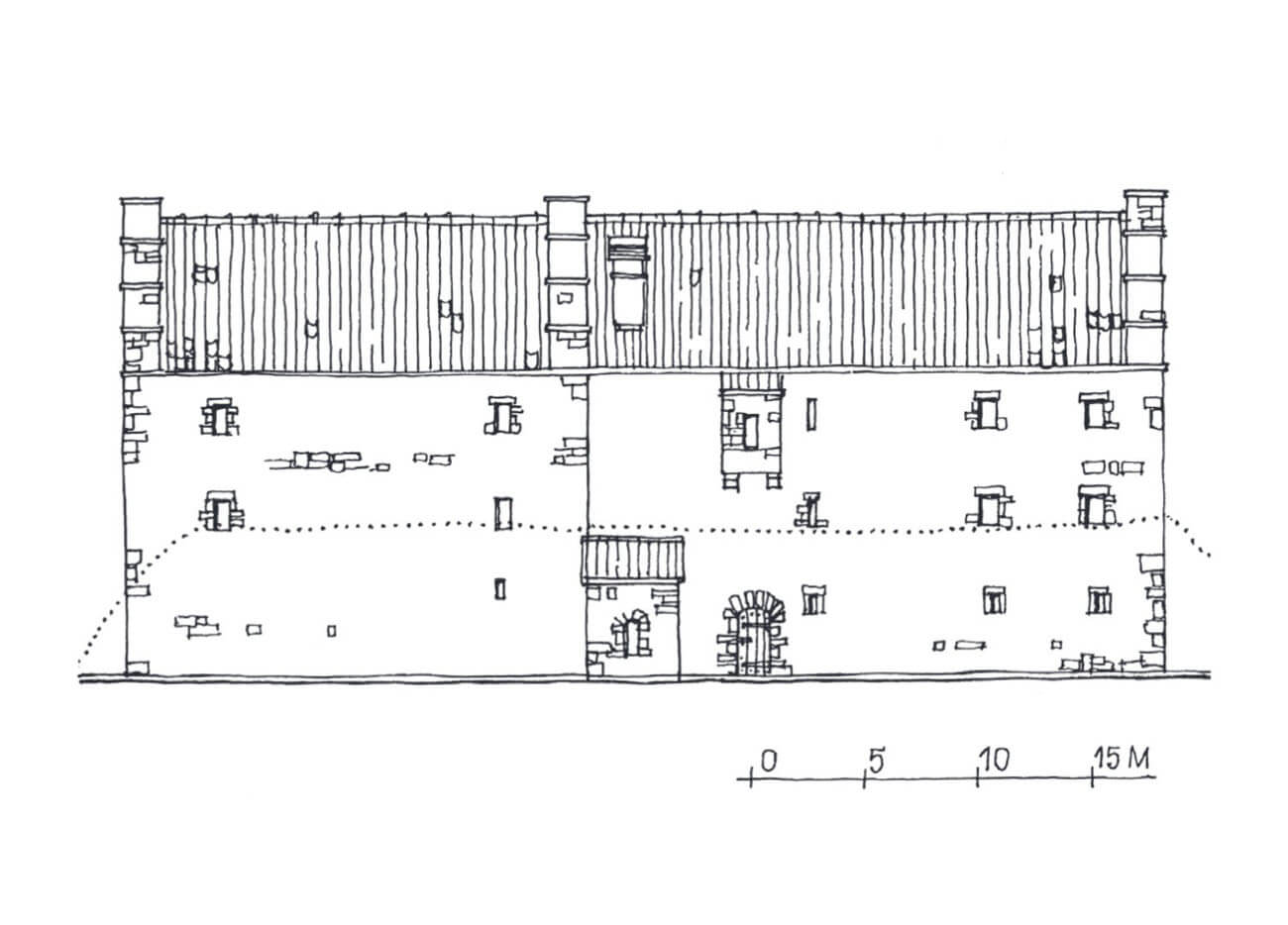

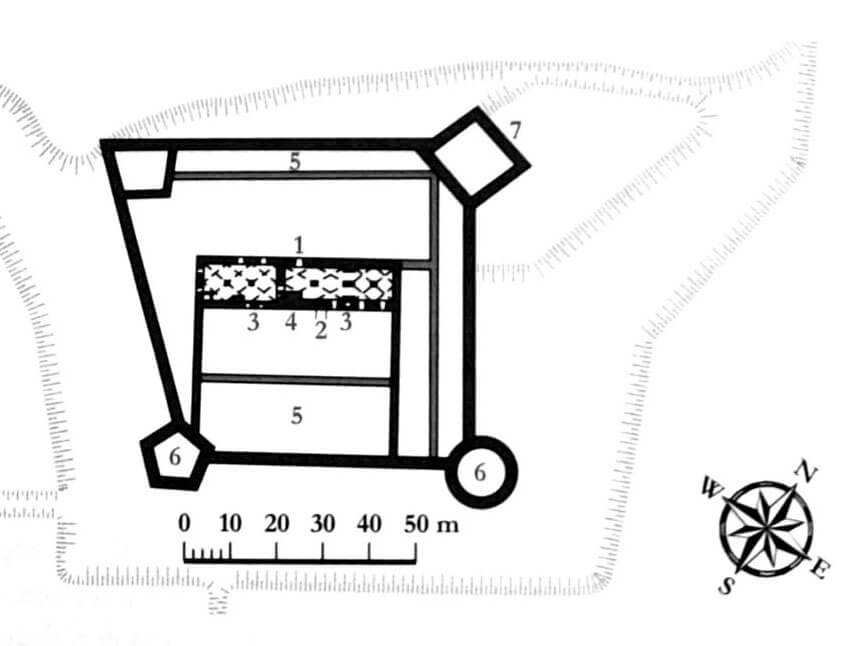

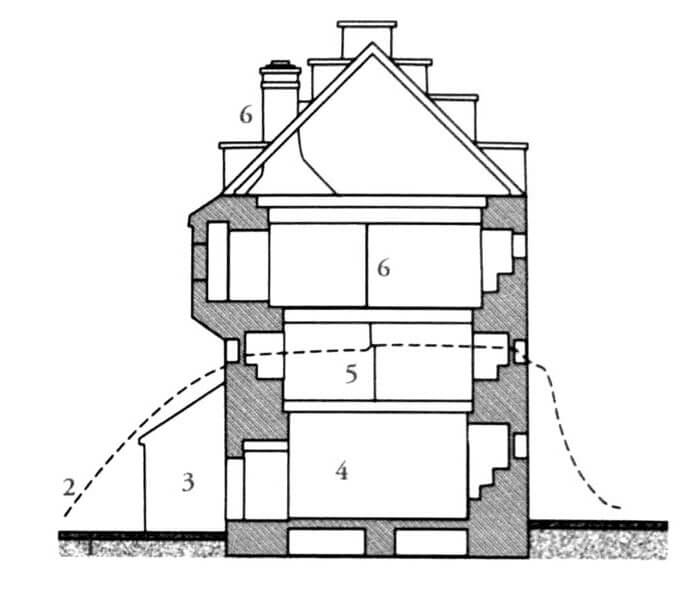

Originally, the castle consisted of a defensive wall on a rectangular plan with dimensions of 54,5 x 42 meters with a four-sided tower-like building in the north-west corner, so it was modeled on the oldest phase of the nearby Arensburg Castle. The tower building had dimensions of 20 x 13 meters and was three storeys high. The defensive wall adjoining it in two corners was about 1.2 meters thick and about 8-9 meters high. After its completion, the building was extended on the eastern side by approximately 26 meters, while the wall on the northern (outer) side was thickened by over a meter. Ultimately, an elongated representative and residential building was created, occupying most of the northern side of the courtyard, with a small free space at the north-east corner. On the opposite, southern side of a small courtyard up to 13 meters wide, there was a narrower building with economic and auxiliary purposes.

The ground floor of the main castle house was occupied by utility rooms. In the western, older part there was a room measuring 20.8 x 12.2 meters with a vault supported by two pillars. In the younger eastern part, there was an elongated chamber 26.1 meters long and slightly smaller in width due to the more massive perimeter walls. On the side of the courtyard there was an elongated vestibule with an entrance at the eastern room. The representative chambers were located on the first floor. It were heated with hot air from a hypocaustum furnace located below. The third, highest floor probably served storage and defense functions. Communication between the floors was provided by stairs placed in the thickness of the wall.

In the 15th century, the main house, the walls connected to it and the second building were surrounded by another, irregular defensive wall on a quadrilateral plan, equipped with at least two towers adapted for the use of firearms. They were located on the most endangered southern side and had a cylindrical form on one side and a pentagonal form on the other. The third, four-sided tower could have been located in the north-east corner. Additional economic buildings were built inside the defensive perimeter.

Current state

Today, most of the outer walls of the castle and towers do not exist. The main house lost part of the first and the entire second floor, and the rubble formed a barrier around the lower parts of the building. Thanks to this, the whole ground floor with vaults and part of the first floor has survived to this day. These rooms have preserved their medieval character and have been made available for exploration after cleaning and securing. It is a pity that the monument from the outside has not been secured in a more eye-friendly way, but only by a tin-metal structure.

bibliography:

Borowski T., Miasta, zamki i klasztory. Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Herrmann C., Burgen in Livland, Petersberg 2023.

Püüa G., Buildings archaeological surveys at Maasi Castle on North-East Saaremaa, „Archeological fieldwork in Estonia 2019”, Tallinn 2020.

Tuulse A., Die Burgen in Estland und Lettland, Dorpat 1942.