History

Sącz was first recorded in 1224, as a castellan hillfort under the name “Sandech” (derived from the diminutive name of Sędomir). The first known castellan of Sącz was a certain Chwalisław, a participant in the meetings called by Leszek the White in 1224 and 1227. He exercised judicial, administrative and military power over the inhabitants of the Sącz land (“terram Zandecensem”), which was received by Princess Kinga from Bolesław the Chaste in 1257. The stronghold itself was recorded in 1288, when “circa castrum Zandech” a Mongol unit was defeated by the Hungarian army coming to Poland’s aid. The stronghold was probably not considered very safe, because Princess Kinga took shelter from the nomads in the castle in the Pieniny Mountains, and in the following years, information about the stronghold stopped appearing in documents. There was only a settlement, the later town of Stary Sącz (“antiqua civitas Sandecensis”), located next to the Poor Clares nunnery founded by Kinga.

In 1292, on the initiative of the Czech King Wenceslas II, a new town of Nowy Sącz was founded in a more defensive place, in the area of the village of Kamienica. Presumably, stone defensive walls began to be built soon after the foundation, as one of the reasons for founding the new town was the desire to improve the defense of the Kraków land. The construction costs were probably borne by Wenceslaus II, because the local merchant community was only at the stage of formation, and Nowy Sącz, considering the scale of the establishment, could have been important for the Czech ruler for prestige reasons. The existence of fortifications was first recorded in 1331, when King Władysław the Elbow-high granted Sącz the right to use the forests near Rytro in order to repair the urban buildings and “blancas” of the walls after a fire. Then, in 1368, King Kazimierz the Great exempted townspeople of Nowy Sącz from paying fees for two years, so that they could enlarge the gate to accommodate a cart from the mill near the town. The end of the building of the stone fortifications of the town probably fell during the reign of the Kazimierz the Great.

The construction of the Nowy Sącz castle could have started in the times of the last two Přemyslids, but it is possible that initially only a less impressive court served as the local royal seat and the place of the Nowy Sącz castellan. In the times of Kazimierz the Great, the castle could have been completed or only rebuilt, because in the second half of the 14th century, royal meetings were held in Nowy Sącz and in 1376, Queen Elizabeth took over the rule of Poland on behalf of Louis of Hungary in Sącz. However, the old court could still have served these purposes, and the stone castle could have been built at the latest at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, when the royal residence was not in use, probably due to construction works. In the Košice privilege from 1374, Sącz was described as “civitates et castra”, similarly the term “castrum” was used to describe the seat in Sącz in a document of Queen Jadwiga from 1396, but in 1384 the same queen described the seat in Sącz as “our court of Nowy Sącz” (“curia nostra Sandecensis”). Similarly, the terms castle and court were used interchangeably in the 15th century.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the defensive walls of Sącz may have required repairs, because in 1410 Władysław Jagiełło ordered his trusted knight Jan from Szczekociny of the Odrowąż coat of arms to repair the town and the castle. As the staroste of Nowy Sącz, he also was to prepare defense in the event of a Hungarian invasion during Poland’s involvement in the war against Teutonic Knights. During the war, the knights of Nowy Sącz, released from the expedition to the north, got tired of waiting and went home, which resulted in Hungarian troops approaching Nowy Sącz and its suburbs. The castle itself and the fortified part of the town were probably not besieged, but the surrounding area was devastated and only Jan of Szczekociny defeated the enemy forces near Bardejov. In 1412, Nowy Sącz obtained a privilege from Władysław Jagiełło, which was intended to help the town in a difficult situation after the invasion.

In 1486, Nowy Sącz was destroyed by a huge fire, after which King Kazimierz exempted the townspeople from taxes for as many as seventeen years. The castle and wooden elements of the town defensive walls were probably also destroyed. In 1522, the castle must have been damaged by another fire, because a year later the starost tried to force peasants from the village of Iwkowa to transport wood for the reconstruction (“ad curiam crematam sue Maiestatis in Nova Sandecz”). This time the losses were probably smaller, because the town books not burned and the proceedings of the starost’s court took place in the castle without any major obstacles. As several town houses were damaged and the townspeople blamed the fire on the starost’s servants, the fire could only spread to the southern part of the castle buildings. When in 1530 King Sigismund the Old bought the starosty and leased it to Jan Pieniążek, the judge of the Kraków land, the starost committed to further repairs to the castle, perhaps related to the washing of the slopes by two rivers.

In the second half of the 16th century, with the support of the king, the modernization of the Nowy Sącz fortifications began, adapted to the use of firearms. In the years 1555-1557, the Hungarian Gate was expanded by new towers next to it. Other elements of the fortifications were also rebuilt, especially the towers. A large investment was the construction of a second, external defensive wall, which gradually surrounded the town from the south and west. These works began in the second half of the 16th century and continued in the first half of the 17th century. The pace of fortification works was temporarily stopped by the town fire in 1611, as a result of which the roofs on the walls and towers burned down. During the reconstruction, staroste Lubomirski carried out a general reconstruction of the castle, as a result of which the main buildings and towers received a Renaissance decoration.

New royal privileges in 1639 and 1649, as well as the war with Bohdan Chmielnicki in 1648 and the entry of the Swedes into Poland in 1655 gave rise to intensified fortification works in Nowy Sącz. It included towers and gates, work on the external wall and earthworks were also continued. In total, in the years 1646-1657, a considerable amount of over one thousand Polish zlotys was spent on town fortifications. Reconstruction after the Swedish wars ended the period of modernization of the defensive walls of Nowy Sącz. In the 18th century, the fortifications deteriorated significantly. Some towers were used as apartments, and the material from the fortifications was used to build houses. Planned demolitions of the fortifications began after the Second Partition of Poland. All three town gates and most of the walls were then demolished. The castle also fell into decline, and its ruin was caused by fires and the collapse of the slope in 1813, as a result of which its part of the buildings and the corner tower fall into the Dunajec River. The last wing of the castle was finally destroyed during World War II.

Architecture

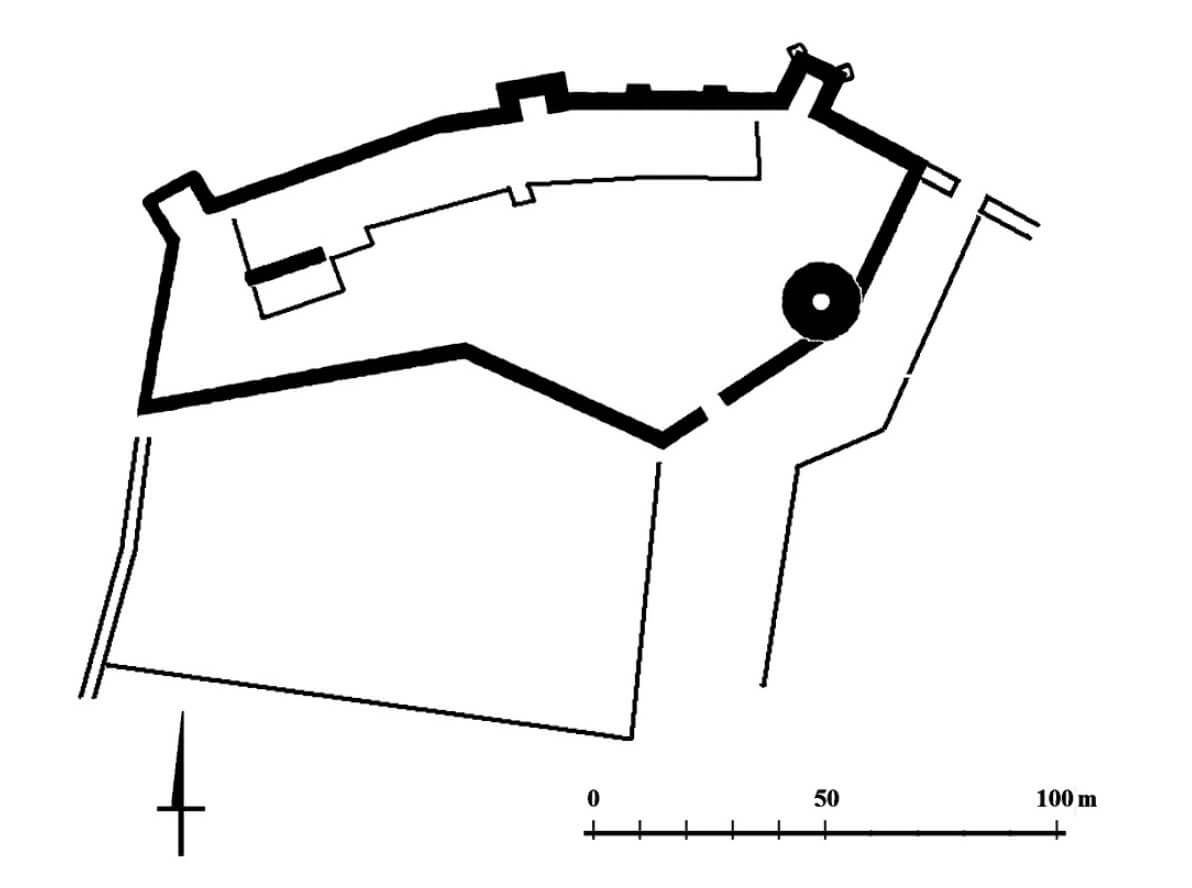

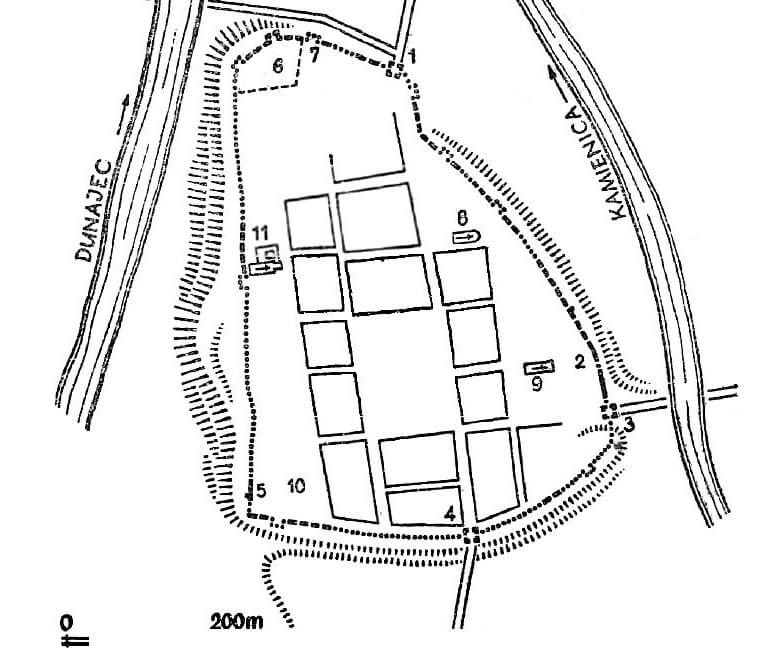

Nowy Sącz was founded at the confluence of two rivers: Dunajec on the western side and Kamienica on the eastern side. The area of the town and the castle was a vast, flattened hill, created as a result of the accumulation of rock material carried by both watercourses. The complex was protected on three sides by steep slopes several meters high. Along edges of the slopes fortifications were built. The highest point of the area was intended for the construction of the parish church of St. Margaret and to mark out a market square, on the northern side of which the ground sloped slightly to reach the second highest place at the confluence of the rivers. This headland was intended for the construction of a castle, integrated with the town fortifications. The ground level in the castle area was approximately 16 meters above the water level of the Dunajec River, so it had significant defensive values.

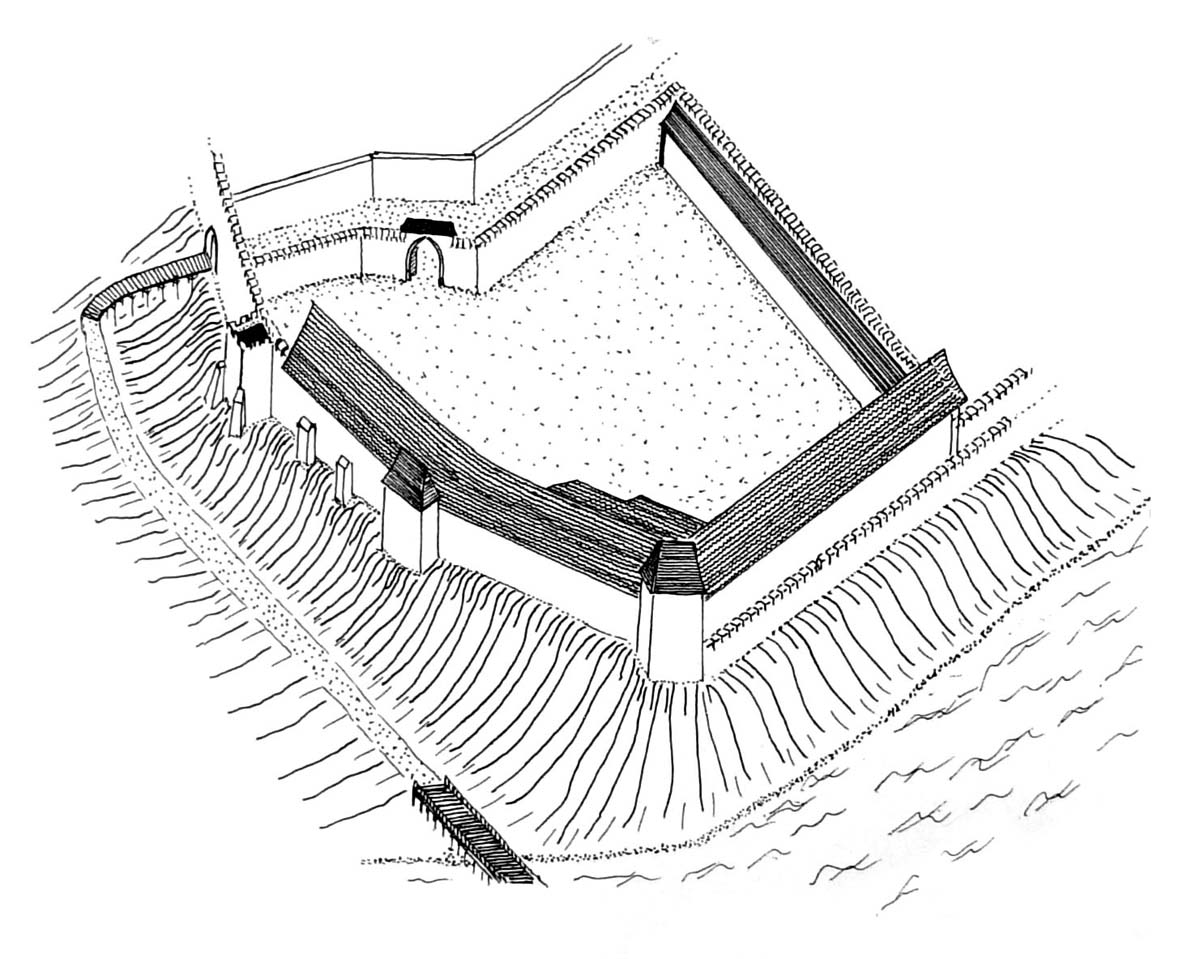

The line of town fortifications created a rather irregular form adapted to the terrain layout. Nowy Sącz was one of the large towns of medieval Poland, with an area of 19 ha, enclosed by a line of walls over 1,700 meters long. Along the walls from the town side there was a strip of land free from buildings, in the Middle Ages occupied only by the castle. The stone defensive wall was topped with a battlement. Its location, running mostly along the upper edge of the slopes, meant that from the beginning it was reinforced from the outside with buttresses. The dimensions of the wall were from 1.4 to 2.3 meters thick and about 5.5 to 8 meters high. During the modernization of the fortifications in the 16th century, the top of the defensive wall changed. The originally battlemented parapet was rebuilt onto the straight one, and the wall-walk received a roof covered with shingles.

It is not known whether the fortifications of Nowy Sącz were equipped with towers from the beginning. This would be suggested by laconic source references, but iconographic records and early modern documents would indicate the functioning of towers already adapted to the use of firearms. In the 16th century, serious construction works were reported on the towers. It could involve a thorough reconstruction of existing ones, as well as the construction of new defensive buildings. Five towers were recorded in documents: three from the east (Pottery, Brewery, Clothery), one in the south-west corner of the town (Huckstery) and one from the west (Butchery). Three more towers were located within the castle area, including the one called Smiths Tower. The spacing of the above towers was very distant, which would indicate their secondary, later construction. Only the castle towers stood at intervals of approximately 50 meters. The town towers had semicircular or square shapes. It were closed from the town side and had tiled roofs. Their interiors were divided into two floors: in the vaulted ground floors there were weapons warehouses, on the upper floors there were firing positions with wooden scaffolding for placing guns and devices for pulling them in. Individual towers and gatehouses were looked after by guilds, from which these objects took their names.

Nowy Sącz had three gates. Two of them: Kraków Gate from the north and Hungary Gate from the south, were located on the main communication route. The third Mill Gate led east. There was also a fourth, later Castle Gate, leading from the town to the castle. The gates probably had the typical form of rectangular gatehouses with passage in the ground floor. Initially, they were very low, about the height of the defensive wall. The Hungarian Gate was the earliest and most extensively expanded. It faced the potentially greatest threat and was located in a place least protected by natural terrain conditions. In the mid-16th century, this gate received two semi-circular towers flanking the passage, probably constituting the end of the foregate.

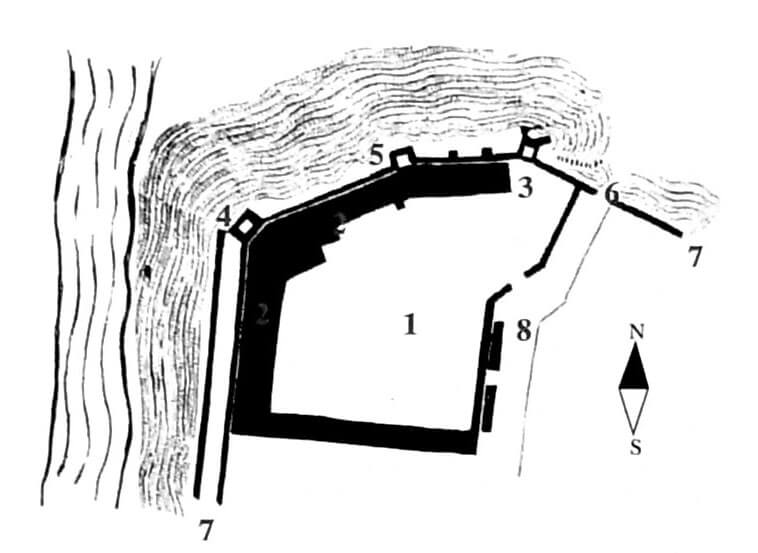

The castle was located within the town walls, at its northern end was in the most exposed point of the area. It was built on the site of a older stronghold or perhaps just a royal court. It was stretched for about a hundred meters along the town walls, to which it was probably added. There were three defensive structures in this section. These were adapted town towers or new towers erected during the construction of the castle. Of these, the Smiths Tower may not have originally been part of the castle buildings, as records state that it was defended by the townspeople, but on the other hand, in the inventory from 1540 it was described as a corner tower of the castle (it was also described as new at that time). One of the two remaining towers was called Nobles Tower and housed a prison cell. Initially, the castle was probably not separated from the town by a wall, but it could have been defended from this side by a moat and an earth rampart. At the end of the Middle Ages, the entrance from the town led through a stone gatehouse with a passage closed by a door and two adjacent rooms on the first floor, accessible via wooden stairs and a porch from the courtyard. At the beginning of the 16th century, and probably earlier, the defensive wall of the castle on the side of the Dunajec and Kamienica was topped with battlements and a covered porch.

The residential buildings of the castle consisted of the main house (the so-called Great House), probably attached to the perimeter wall between the Smiths Tower and the middle tower. It was supposed to be a two-story building with a basement. In the first half of the 16th century it had four rooms on the ground floor and four on the first floor. Those on the first floor probably had representative functions. They were heated by a tiled stove and a fireplace. Perhaps one of the rooms also housed a castle chapel. In the western part of the courtyard there was a late medieval, free-standing (not attached to the defensive wall), rectangular building, about 28 meters long and 13 meters wide, with its longer side facing the Dunajec River. It was made of sandstone bonded with lime mortar, creating massive walls 1.7 to 2.1 meters thick, which were built in two stages. It did not have a basement, but the large width of the walls would indicate that it had an upper floor. The ground floor probably housed a kitchen, a brewery, a room with a stove, and a large room on the first floor. In the courtyard there was to be a well with stone lining and economic buildings (e.g. stables). Interestingly, in the courtyard there was also a linden tree with fenced benches and tables.

From the west, north and east, the town was well defended by slopes. However, the southern side, deprived of natural protection and defending the town from the side of the greatest threat, was secured with an additional moat and an earth rampart. The defense belt from the south and west was expanded, among others in connection with the construction of the outer wall. It formed a relatively narrow zwinger, perhaps reaching as far as the castle grounds. At the end of the Middle Ages, under the castle there was supposed to be a garden and a pasture, and a little further away there was a farm where cattle was kept for the needs of the royal court.

Current state

The best preserved relic of the defensive walls of Nowy Sącz is located in the eastern part of the town, behind the church of St. Margaret. It is over 20 meters long and 1,4 meters thick. To the south of it, at Zakościelna street, there is over forty meters of wall, completely reconstructed in 1918. At the northern end of the town there are the remains of the castle with the reconstructed square Smith Tower on renaissance forms. A fragment of the defensive wall adjacent to it has reconstructed timber porches with a roof.

bibliography:

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Moskal K., Zamki w dziejach Polski i Słowacji, Nowy Sącz 2004.

Olszacki T., Rezydencje królewskie prowincji małopolskiej w XIV wieku – możliwości interpretacji, “Czasopismo Techniczne”, zeszyt 23, 2011.

Rajman J., Zamek królewski w Nowym Sączu (około 1300-1611), Kraków 2023.

Sypek A., Sypek R., Zamki i obiekty warowne ziemi krakowskiej, Warszawa 2004.

Widawski J., Miejskie mury obronne w państwie polskim do początku XV wieku, Warszawa 1973.