History

The beginnings of a defensive court in Tretower date back to the early 14th century. Then, after the defeat of the Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffydd and the occupation of Wales by the Anglo-Normans, there was a break in armed conflicts. For this reason, the owners of the small castle in Tretower, the Picard family, decided to improve their housing conditions and move to a larger and more comfortable residence.

At the beginning of the fifteenth century, due to the Welsh uprising of Owain Glyndŵr against king Henry IV, the building was in danger. The nearby castle was attacked, but Sir James Berkeley successfully repelled the attackers. The court probably also escaped more serious damages. In 1404, the battle of Mynydd Cwmdu was fought nearby, between the English army commanded by Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, and the Owain’s Welsh army, as a result of which the leader of the insurgents was almost caught. Less than a decade later, the court was a gathering place for Welsh archers to serve king Henry V in France and contribute to the victory of the English in the Battle of Agincourt.

In the initial period, the lands around Tretower were owned by the already mentioned Picard family (Pychard), which acquired extensive lands in Herefordshire in exchange for the help given to William the Conqueror. The next owners of the court were William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke and his half-brother, Sir William Herbert. Around 1450, they transferred the estate to Sir Roger Vaughan. The new owner made a significant reconstruction and extension of the court.

Roger Vaughan during the War of the Roses belonged to the York House, fighting in the battle at Mortimer’s Cross in 1461 and leading Owain Tudor to the execution after the battle. In 1465, he suppressed the uprising in Carmarthenshire, and soon after he was knighted. In 1471, after the Battle of Tewkesbury, he chased Jasper Tudor, but this time the roles were reversed, Tudor himself caught Roger and cut him off at Chepstow Castle.

The son and heir of Roger Vaughan, Sir Thomas Vaughan, continued to expand the court in the last quarter of the 15th century, reinforcing it with a defensive wall and a gatehouse. Further modernizations were carried out in 1630 by Charles Vaughan, the sheriff of Brecknock, who remodeled the west range. Charles handed over court to his son, Edward Vaughan, but he died without posterity, and the estate passed to his sister, Margaret of Maes-y-Gwartha, married to Thomas Morgan. Over the next years, the court often changed owners, but it was not significantly rebuilt, but fell into negligence, serving as a barn, a pigery and a warehouse. It was not until 1929 that the Brecknock Society appealed from the government for the purchase of the building. In the 1930s, it was saved as a result of the renovation carried out at the time.

Architecture

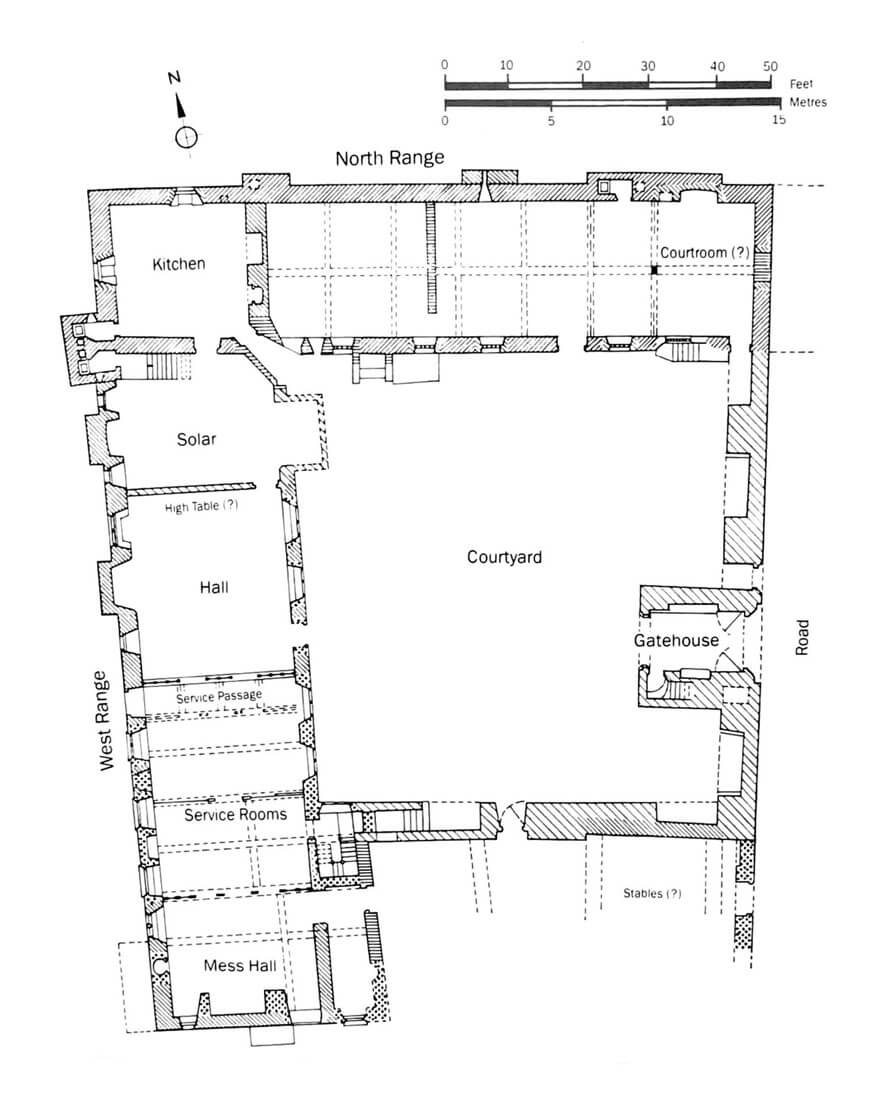

The oldest part of the court was the 14th-century northern rectangular wing with a four-sided latrine bay located at the west facade. A second, slightly shallower latrine bay was placed in the western part of the northern facade. In the interior of the north wing, originally at the ground floor, there was a great hall in the middle, open to a high roof. The first floor of the building, initially accessible via wooden internal stairs, was occupied by a private chamber (solar) and a bedroom, both in the western part, while in the eastern part there was an additional living room. The great hall, like in most castles, served as a representative chamber, a place for feasts, ceremonies and important meetings. The building’s lighting was initially provided by simple pointed windows, and fireplaces gave heat (fireplace from the fourteenth century has preserved in the eastern room). The main entrance was at the courtyard level, in the eastern part, in a simple ogival portal. A second but smaller entrance portal was placed in the western part of the wing.

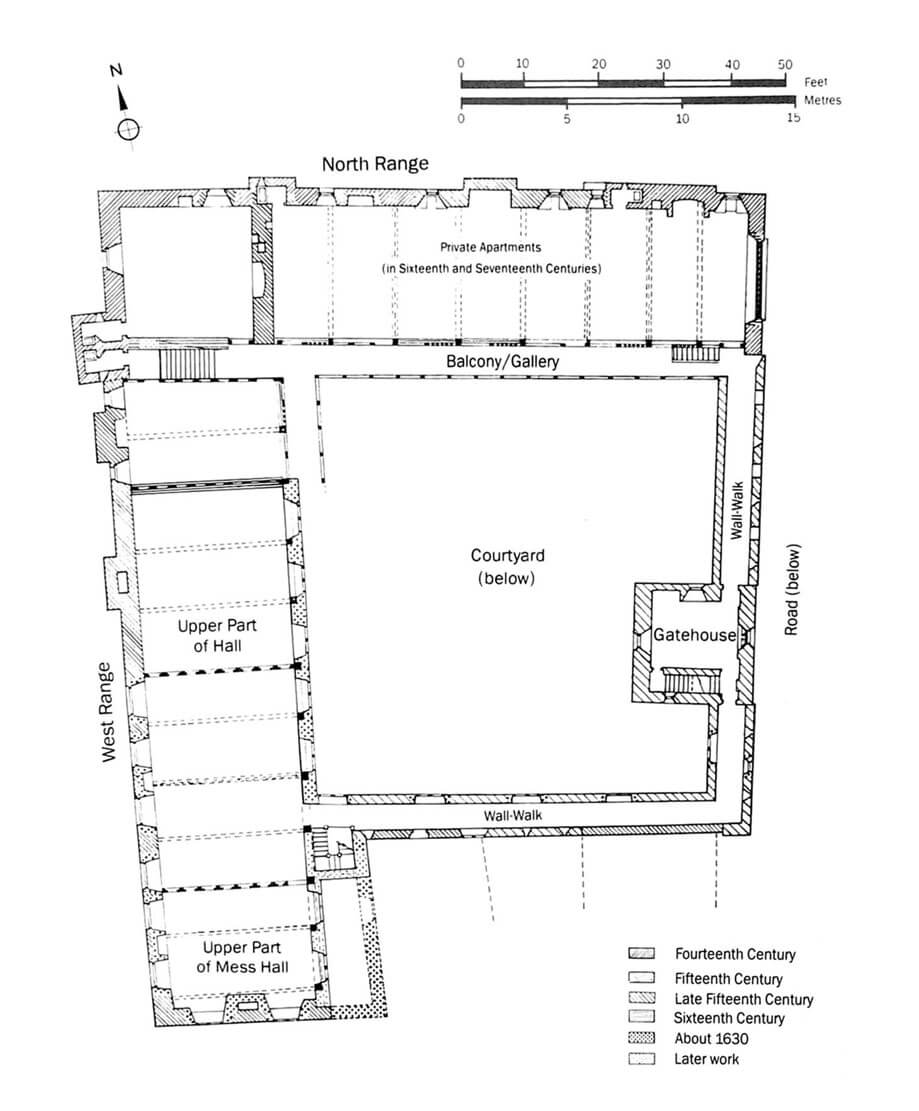

In the fifteenth century, the northern wing was rebuilt. It received an additional storey on the site of the older hall, thanks to which the entire building became a two-story building. The lower floor began to serve as a pantry and a kitchen at the western end. The latter was fenced off with a new stone wall. In the eastern part of the ground floor there was a room, probably intended for a local court, in which fines and tithes were paid. From the west it was adjacent to the room with a latrine in which the steward could live. At the top, the old purpose of the rooms was preserved, while the new central chamber began to serve as a half lower hall, and the eastern part of the floor was divided with wooden or half-timbered partitions into two rooms with a latrine. They were probably intended for guests. A suspended gallery (balcony) of a half-timbered structure was added from the outside to the south wall of the building. Thanks to this, the residents of the upstairs chambers could maintain greater privacy, by accessing each room directly from the courtyard. Interestingly, the southern wall at floor level (like the later eastern wall of the floor of the west wing) was not stone one but only half-timbered. It was pierced with simple, four-sided windows closed with timber shutters.

In the 15th century a long west wing was also built, attached perpendicular to the north one. Inside it, on the ground floor level, there was a 8-meter long, three-bay new hall covered with an open roof truss. Its heating was provided by a large fireplace placed in the middle of the outer wall, flanked by two high windows. The window on the north side was larger and was probably intended to illuminate the table of the lord. In addition, on the first floor of the west wing there were residential chambers (accessible via stairs in the thickness of the southern wall), and in the southern part a two floors high mess hall for retainers and men at arms. It was adjacent from the north to the ground floor four small rooms where meals and drinks were prepared. Between them and the hall in the north, a transverse service passage 1.8-meter wide was squeezed, connecting all the rooms and the courtyard (where the originally timber vestibule could have been) with the meadows on the west side of the court. All internal divisions were originally created using wooden or half-timbered screens. The windows of the new wing were more sophisticated. Most often they were in the form of two-light openings with trefoil finials and with a transverse, horizontal frame.

In the last quarter of the fifteenth century, a defensive wall was erected from the south and east, which, together with two wings, closed the internal courtyard. The wall had a prominent parapet on corbels and was topped with a wall-walk for defenders protected by battlement. In the merlons, loop holes of a form similar to those used in the Tretower Castle and White Castle were pierced. In the 17th century, the defensive wall-walk was roofed.

The gate was placed in a four-sided, three-story gatehouse in the eastern curtain. The passage had a vault and a richly moulded ogival portal, above which the upper part of the building was supported by massive protruding corbels. An empty space between them was preserved, similar to the machicolations, thanks to which the guards could extinguish a possible fire from the outside of the door or shoot the attackers. A smaller wicket gate also led to the inner courtyard, located next to the main gatehouse. Inside the gateway on the sides, stone seats were placed in niches and a passage leading up the stairs to the upper floor and to the wall-walk in the crown of the defensive wall. The first floor of the gatehouse contained a single room heated by a corner fireplace and illuminated by large windows.

At the end of the 15th century from the courtyard side, a decorative bay window pierced with four openings with quinquefoil finials was placed in the west wing, while in the 16th century in the northern wing a basement was created. Stairs from the courtyard level began to lead to the underground rooms with the barrel vault, which forced the building of an alternative entrance to the north-west room at the ground floor. Also a large window was added to the eastern wall of the northern wing to illuminate the upper chamber.

Current state

Tretower Court is a unique, rarely seen example of a medieval manor, which, over the centuries, has avoided destruction and significant transformations. The changes from the 16th and 17th centuries were mainly limited to the west wing, where new windows were pierced, two fireplaces with prominent chimneys in the south-west facade were added, and small changes were made to the interior layout of the rooms. For a change, the northern wing, which lost its significance in the early modern period, has not been further transformed. Court is open to visitors together with the nearby castle from March 24 to November 4 from 10:00 to 17:00.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Radford R., Robinson D., Tretower Court and Castle, Cardiff 1990.