History

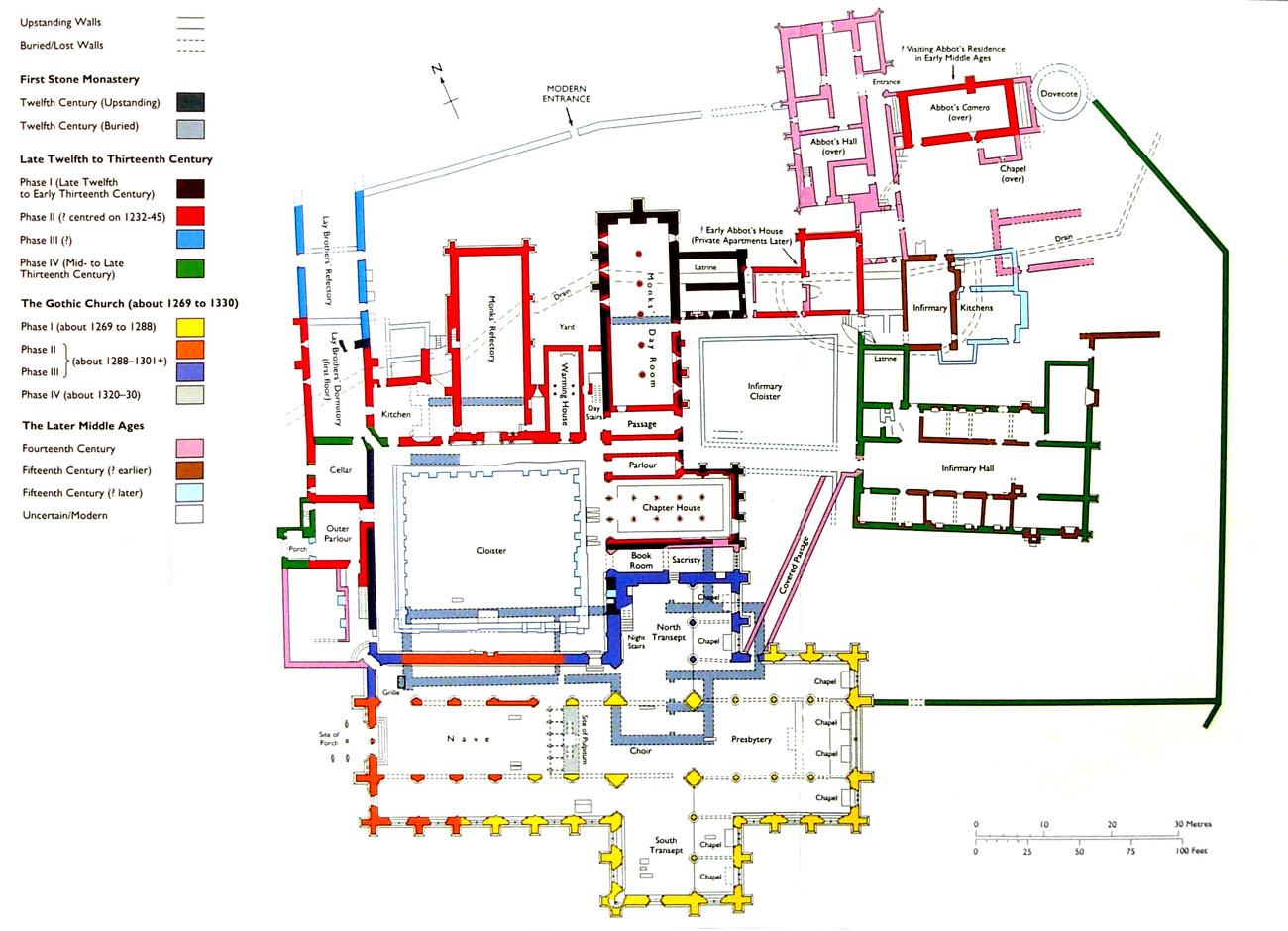

Tintern Abbey was founded in 1131 by Walter de Clare, Lord of Chepstow. Walter was related by family to William, Bishop of Winchester, who founded the oldest Cistercian monastery in Britain at Waverley, and thus likely decided to bring monks of the same order. Tintern was the second Cistercian abbey in Britain and the first one in Wales. The monks came from the monastery of L’Aumône, in the diocese of Chartres in France. They followed the rule of St. Benedict, and their main, strict principles were obedience, poverty, chastity, silence, prayer, and work. They usually established their monasteries in secluded places, far from larger settlements, and initially they were characterized by simplicity and a rejection of ostentatious decoration. However, by the end of the 12th century, the rule had been relaxed, contributing to the economic development (the ability to accept lay brothers) and the architectural development of Cistercian monasteries.

During the abbey’s initial period, it was granted extensive lands on both sides of the River Wye, and even in England. These were divided into agricultural units or farms (grangies), on which local people worked and provided services. The success of the foundation and the successful early years were evidenced by the fact that, just eight years after the abbey’s founding, some of the monks from Tintern were sent to the daughter monastery at Kingswood in Gloucestershire. The abbey likely experienced rapid development under the energetic Abbot Henry between 1148 and 1157. However, prosperity may have temporarily slowed down around 1169–1188, when Abbot William became embroiled in a dispute with Waverley and was ultimately forced to resign following an inspection by the General Chapter. Despite this, by the early 13th century, with the support of William Marshall, first Earl of Pembroke, the monks of Tintern had already established a second daughter monastery, the Irish Tintern Parva. They also found a generous donor in the younger William Marshal, second Earl of Pembroke, from whom they acquired arable lands on the northern reaches of the River Usk. Thanks to donations, income from farms and church tithes and own labor, by the end of the 13th century the monastery already possessed over 3,000 acres of arable land and nearly 3,000 sheep.

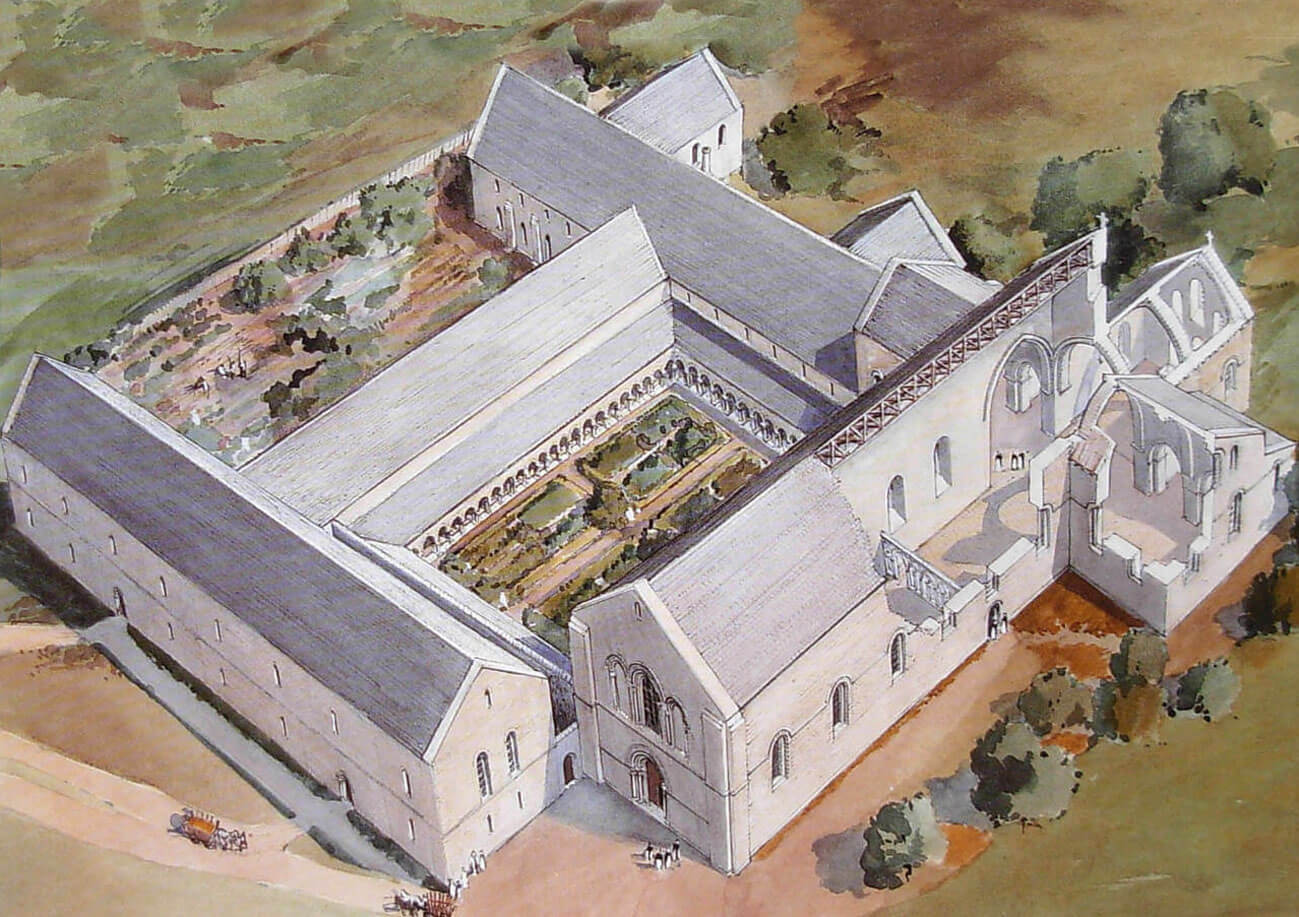

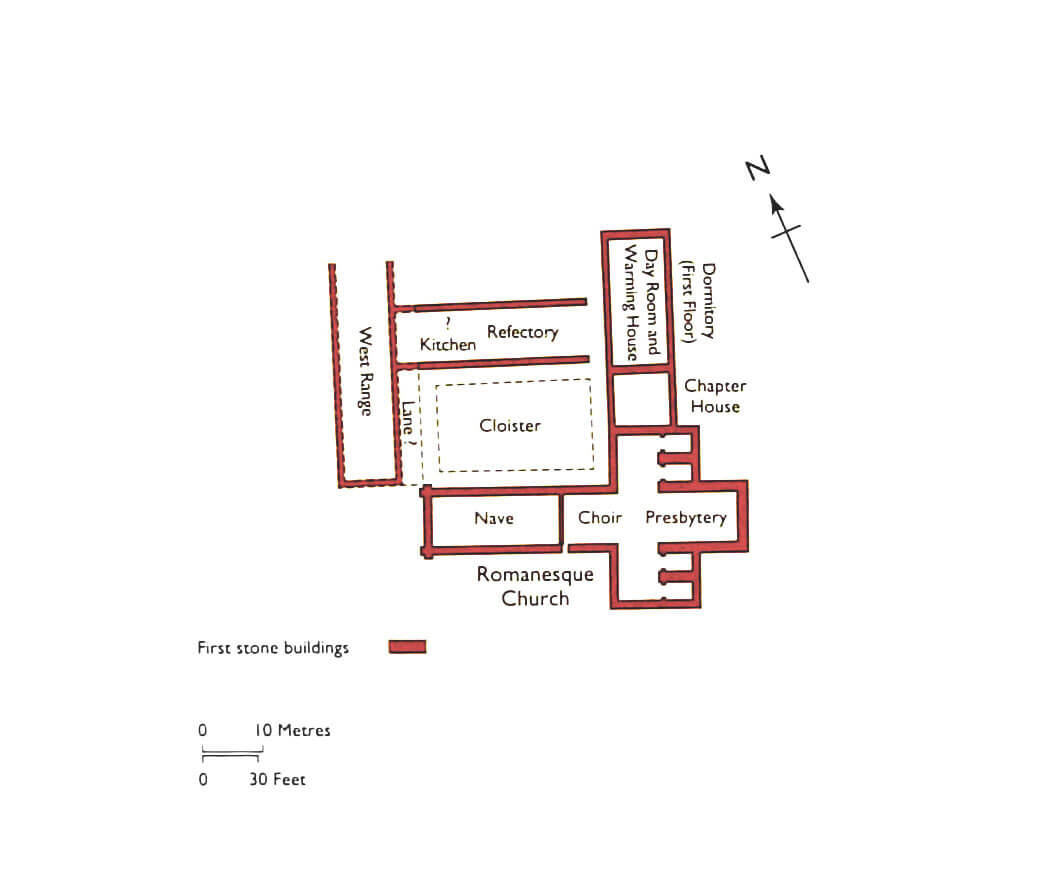

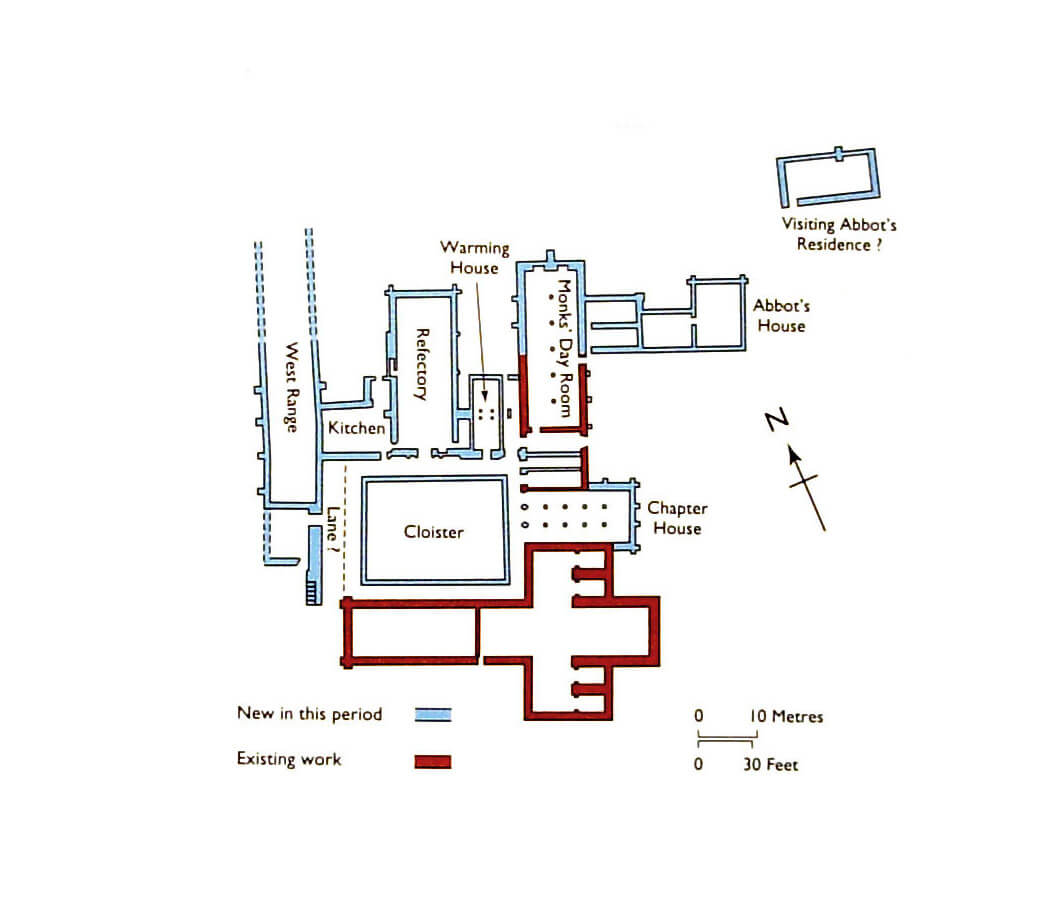

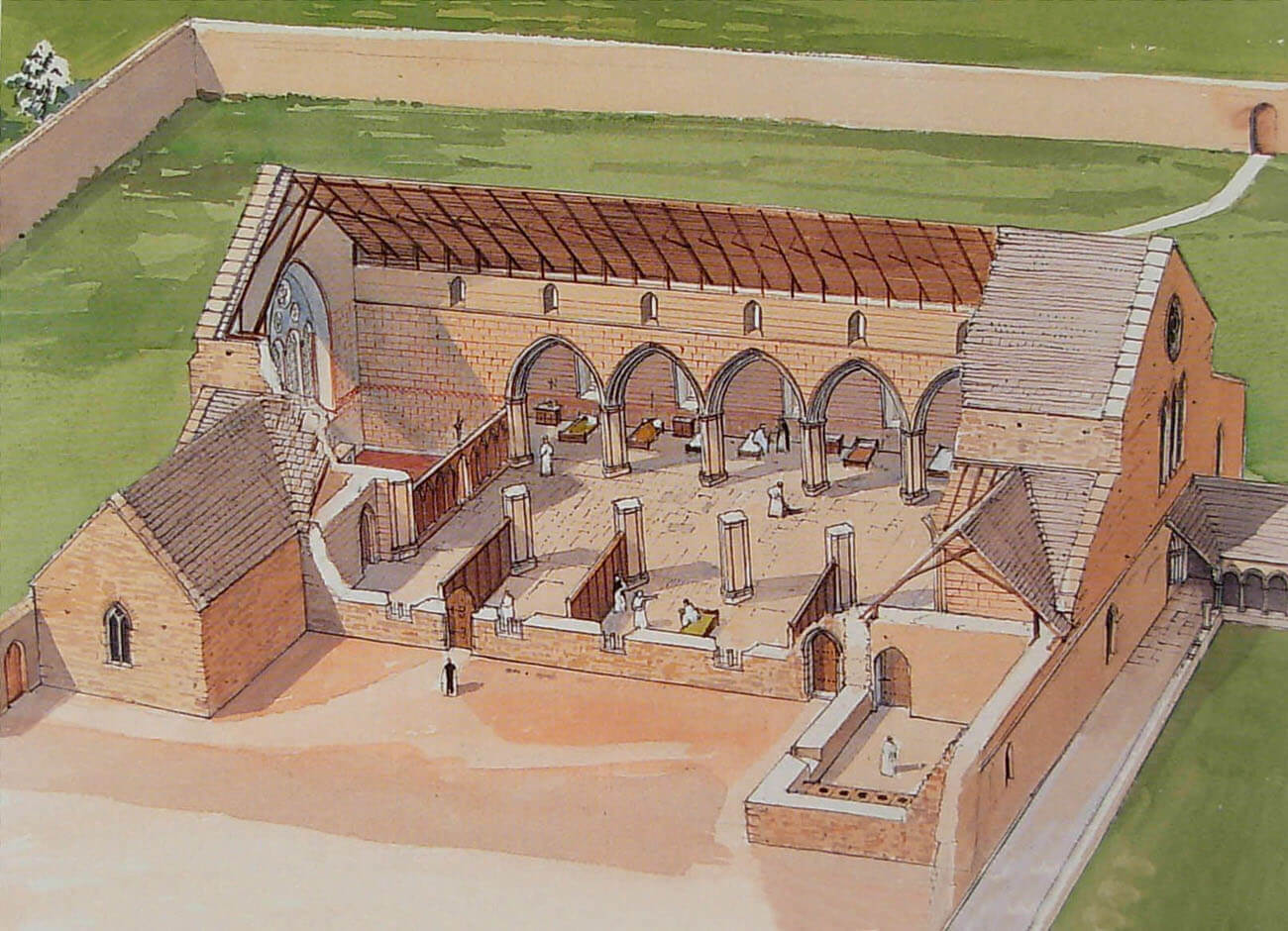

The oldest monastery buildings, likely still wooden, began to be built shortly after the first monks arrived in Tintern. As the abbey’s position became secure and the community of monks began to grow, the construction of more permanent structures became necessary. The first Romanesque church was likely built by the mid-12th century, during the time of the aforementioned Abbot Henry, a converted former thief. Work on the monastery buildings surrounding the cloister was certainly well underway during this period, and were completed in their original form before the beginning of the 13th century. Despite this, construction work at the abbey practically never stopped. In the 1220s or 1230s, a Gothic reconstruction of the refectory and the entire north and east wings began, and around the mid-13th century, modernization of the west wing and cloisters continued. In the second half of the 13th century, the most significant new building was the infirmary, initially located somewhat apart and intended for the sick and elderly monks.

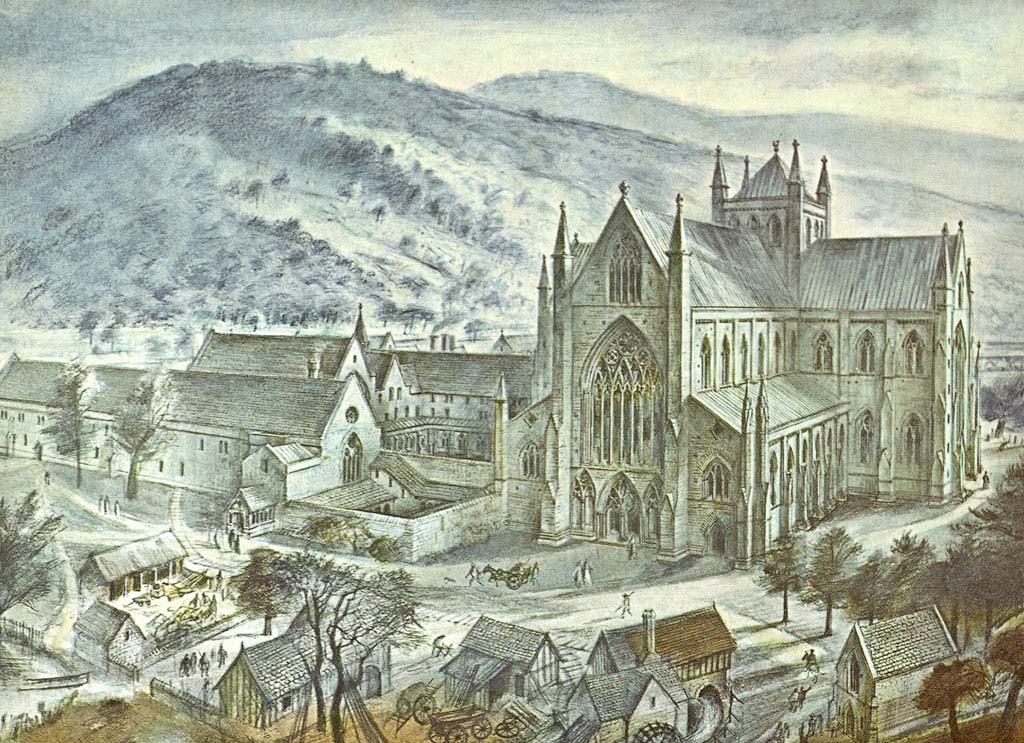

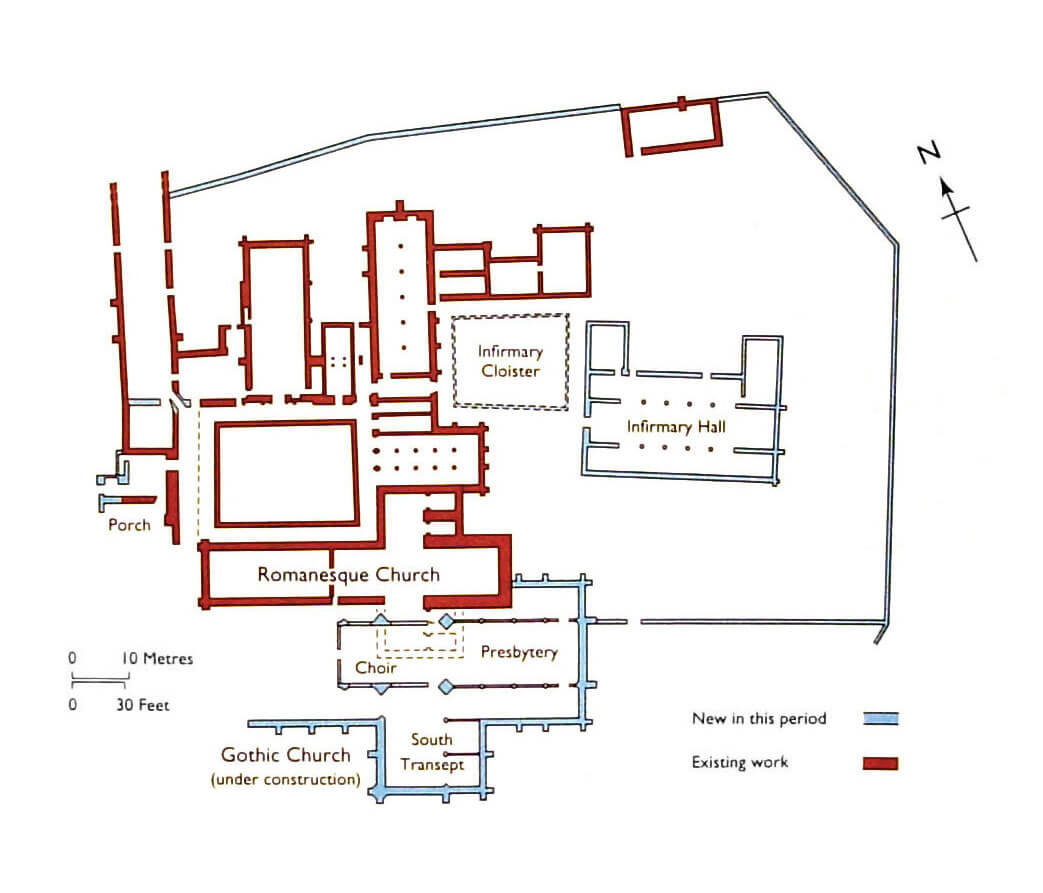

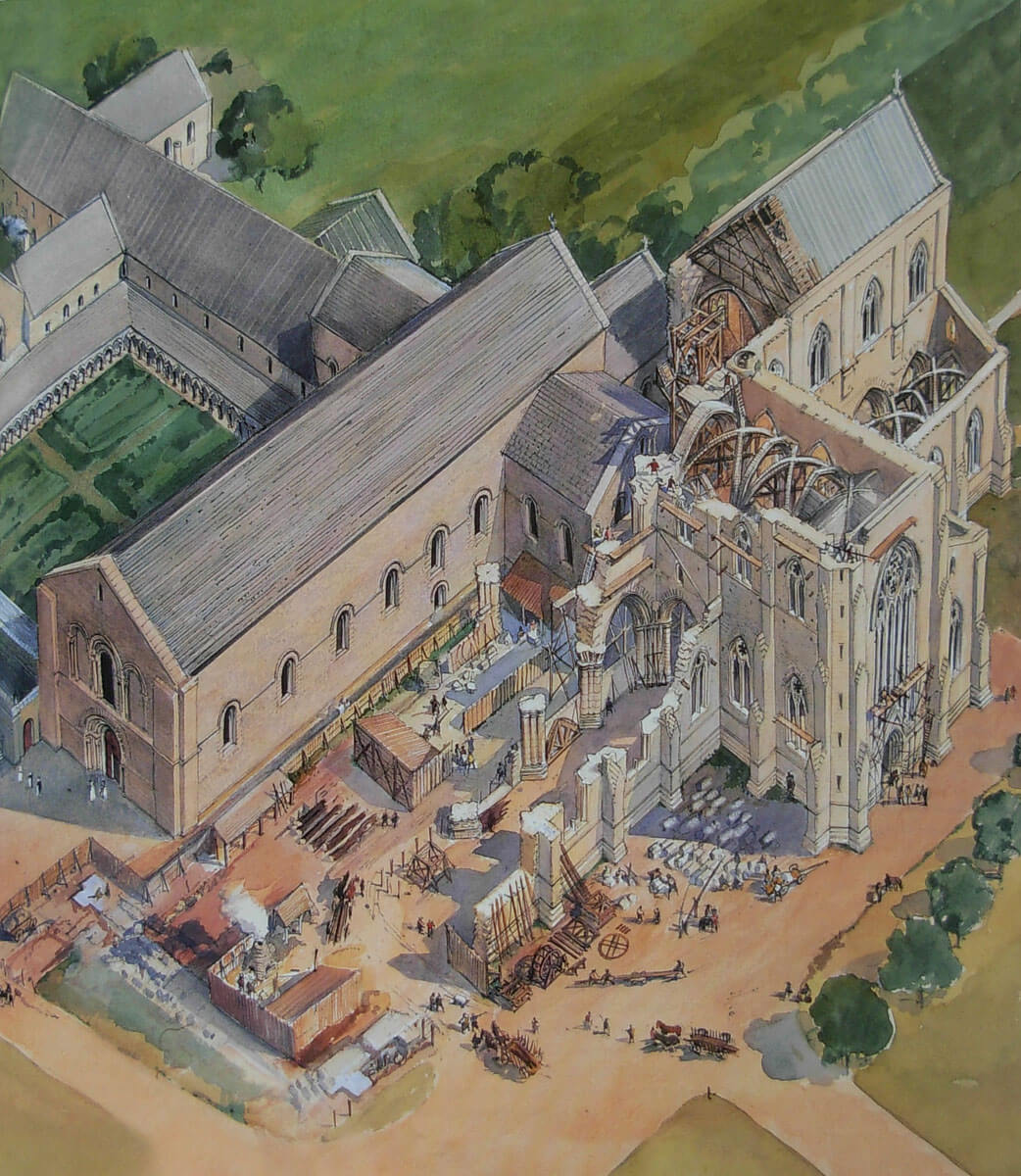

In 1269, during the reign of Abbot John and with the generous support of Roger Bigod III, Lord of Chepstow, Tintern undertook the largest building project in the abbey’s history: the construction of a new Gothic church. Construction began on the eastern side, alongside the older church, so that it could continue to serve liturgical functions during the long construction period. When the chancel and south transept were completed in 1288, services could be held in the new church, and the old one could be gradually demolished to make way for a new nave and north transept, with the demolition materials being used to further building. The church’s reconstruction was finally completed in the early 14th century, although work on expanding other parts of the abbbey continued, with varying degrees of intensity, until the late 15th century. At that time, the large abbey could accommodate around twenty monks and fifty lay brothers.

Tintern was one of the few Welsh abbeys to escape the devastation of Edward II’s wars. This was undoubtedly due to its remote, isolated location and its lack of clear allegiance to either side. It is known that Edward II was at the abbey for two nights in 1326, when he stayed with Abbot Walter of Hereford while fleeing Roger Mortimer’s army. Despite the offered hospitality, no record of the monks experiencing any trouble or facing any accusations from the opposing side of conflict was made. However, disciplinary problems and the first serious economic difficulties were mounting in Tintern at this time. For example, between 1330 and 1334, a conflict raged over the abbey’s fishing rights on the River Wye, where the monastery’s weirs had expanded to such a scale that travel was difficult. Henry of Lancaster complained to the king about the difficulties in sending supplies to Monmouth, but ultimately he achieved nothing, and the monks even attacked the officials sent to lower the weirs. A few years later, in 1340, the abbot of Tintern was recorded as owing a considerable £174 debt, likely resulting from further construction work on the abbey grounds. Because of this, and also due to the general economic trend affecting the Cistercians at the time, some of the abbey’s property had to be leased out.

In the mid-14th century, the abbey faced difficulties due to a shortage of workers, who died out due to the epidemic known as the Black Death. This affected both ordinary farm workers and the monks from the church choir. Despite the reduced number of monks, by the end of the century Tintern was a relatively stable community, comprising fourteen monks and Abbot John Wysbych. It wasn’t until the early 15th century that more serious financial problems arose, as a result of Owain Glyndŵr’s Welsh uprising. In 1406, a royal letter to the Bishop of Hereford noted that most of the abbey’s property had been looted or destroyed by rebels. At that time, the abbey was saved by donations from pilgrims who visited the abbey, as its chapel in front of the main entrance to the church housed a statue of the Virgin Mary, which the visitors believed possessed miraculous powers. In 1414, in connection with the chapel and some construction work, Pope John XXII issued an indulgence for all those who supported the abbey with donations on specific feast days.

In 1535, the abbey’s annual income was valued at £192, making Tintern the richest monastery in Wales. Furthermore, a further inventory of the abbey’s property the following year revealed a higher value of £238. Despite this, it was subject to King Henry VIII’s first Act of Suppression, which dissolved all monastic houses under an annual income of £200. Consequently, the abbey buildings were granted in 1549 to Henry Somerset, Earl of Worcester, and all valuable items from the monastery were catalogued, weighed, and sent to the royal treasury. Other, less valuable items were likely auctioned off on site. Somerset then demolished the roofs to extract the precious lead, which began the deterioration of the medieval buildings. Over the next two centuries, interest in Tintern was minimal. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the ruins were inhabited by workers from local factories. In the mid-18th century, visiting “romantic” and picturesque locations became fashionable, and the first conservation and research efforts were not undertaken until the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Architecture

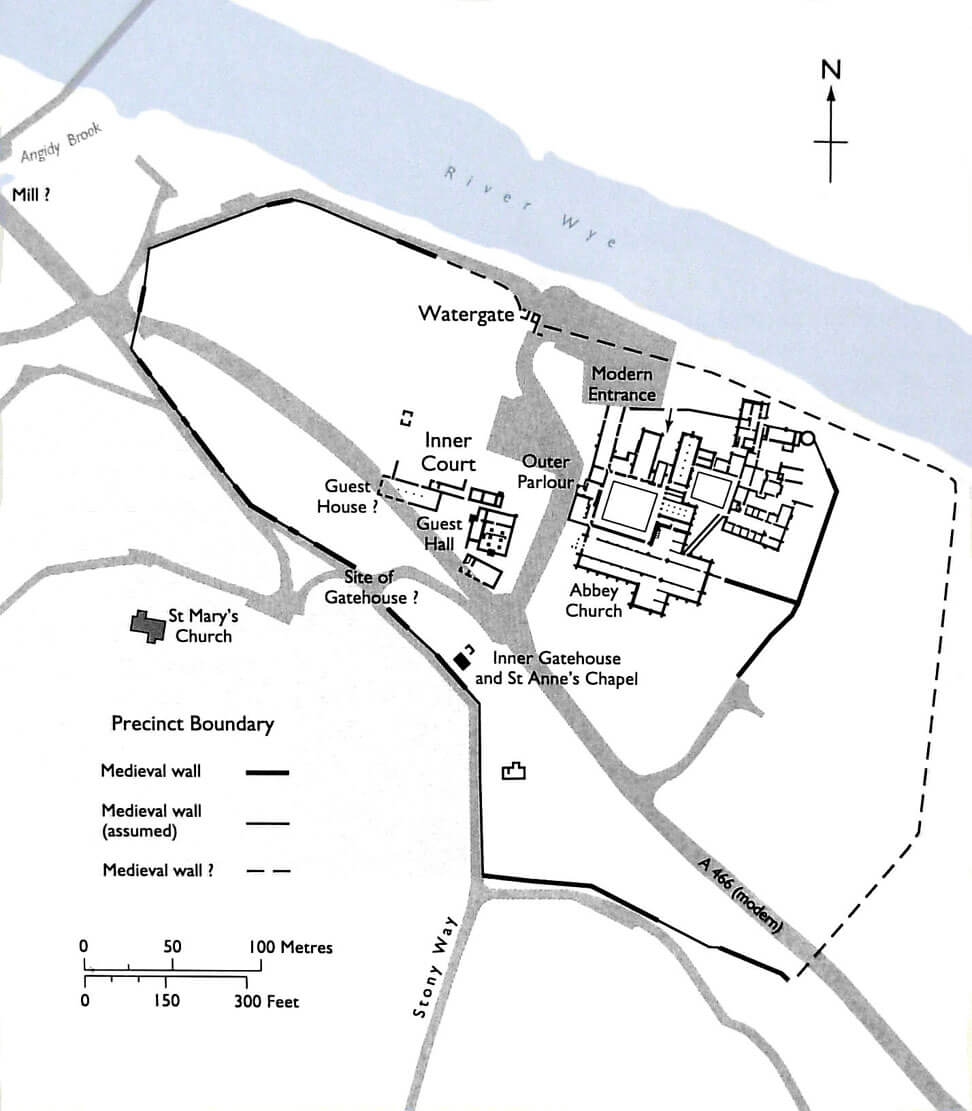

Tintern Abbey was founded in the Wye River Valley, whose steep, wooded slopes concealed the buildings and made them invisible from a distance. This was consistent with the monastic rule, which mandated the construction of a monastery in inaccessible areas, far from human habitation, and also enhanced the security of the abbey, which lacked significant fortifications. The river bordered the abbey on the north. To the northwest, the smaller Anghidi River flowed into the Wye, and to the south, several streams flowed down from the hills. Together with the river, the Cistercians used these streams to create a system of canals providing water for wells, kitchens, and latrines. To the east of the abbey, a slight bend of the river separated a section of flat land with floodplain meadows. The road connecting Chepstow in the south with Monmouth in the north likely ran more or less along the riverbed.

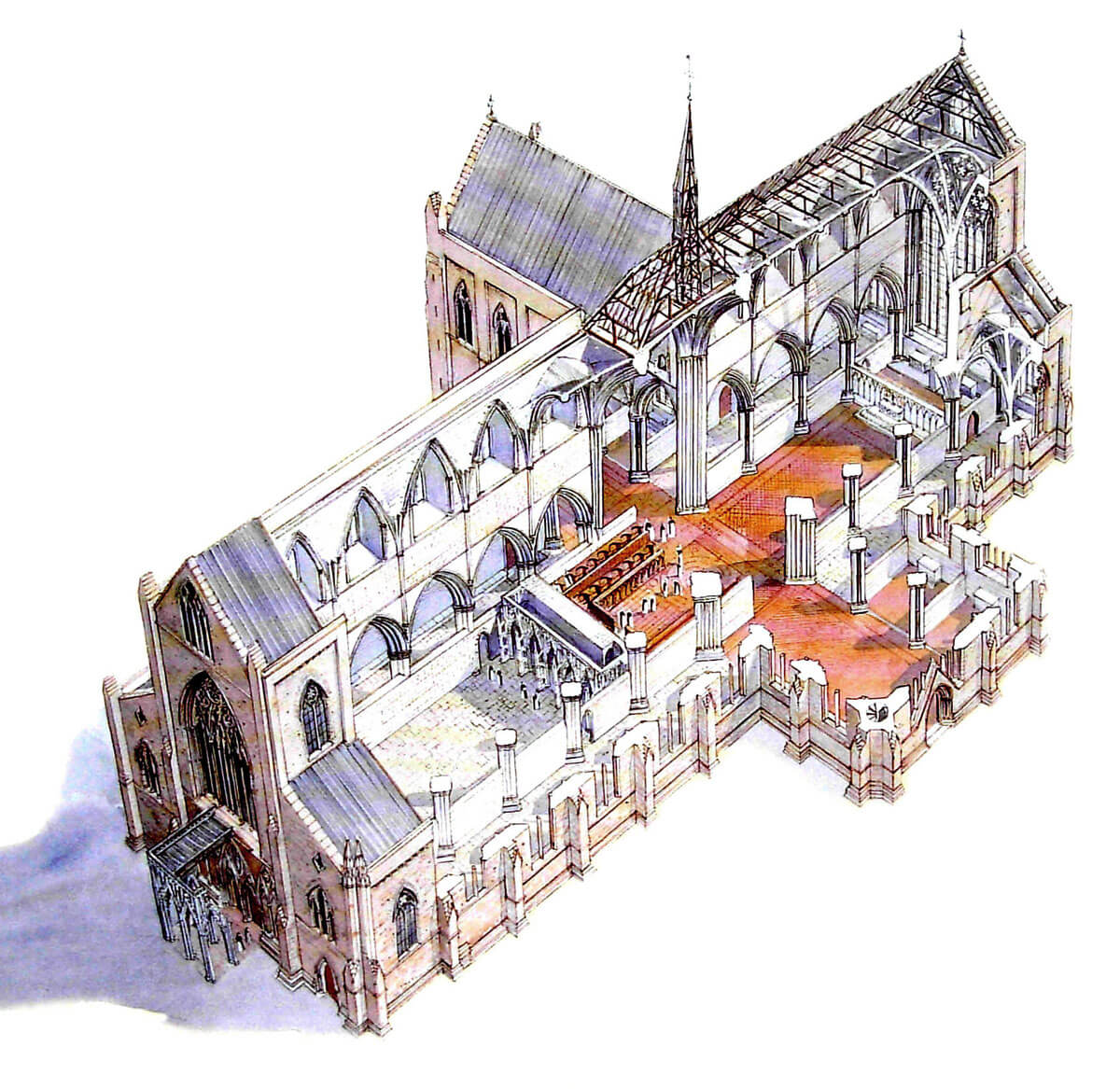

At its peak, the monastery complex occupied approximately 27 acres of land, protected by a wall approximately 3 meters high. This wall may have surrounded the abbey along its entire perimeter, or only on the landward side, with a break on the eastern side, where steep slopes descended to meadows and the riverbank. Entry was provided by at least two gates: one on the southwest side, where land routes intersected, the other on the north side, overlooking the river and the ford. The former likely adjoined a gatehouse with a vaulted passageway, later converted into St. Anne’s Chapel, located slightly further away. After passing through the gate, the road led northwest to the monastery’s economic buildings (barns, stables, granaries, etc.) and northeast, where the church and the most important buildings of the claustrum were located. As access to this part was reserved for monks only, in the northwestern part, in addition to the economic buildings, there was also a guesthouse, a two-aisled building with a central hearth inside. Additionally, to the west, outside the perimeter wall, was a watermill located at the confluence of the Anghidi with the River Wye.

The original mid-12th-century church was built on a Latin cross plan, with a small quadrangular chancel and a narrow but relatively long nave, measuring approximately 52 meters in total. Wide transepts were located on the north and south sides, each with two small chapels on the eastern side. Like the chancel, the chapels were ended on the eastern side by straight walls, without the addition of apses. A tower was most likely not built at the crossing, in accordance with the original guidelines of the strict Cistercian rule. The church was therefore relatively modest, built in the Romanesque style. Its western corners were reinforced by pilasters, and lighting came from small, splayed windows with semicircular arches. The external entrance was in the southern wall of the choir, but the main portal likely pierced the western wall of the nave. Since the eastern part of the church had thicker walls, it’s likely that both the chancel and transept were topped with a barrel vault. The nave had only a flat wooden ceiling or an open truss, and its roof was higher than that of the chancel.

The claustrum buildings were built somewhat unusually, on the north side of the church rather than on the south, as was most common, likely to better utilize the narrow strip of flat land and access to the river. The oldest eastern wing adjoined the northern transept. Originally, it was rectangular, 8.5 meters wide. On the ground floor, next to the church, it housed the chapter house, and in the northern part an elongated day room for handicrafts, and a separate warming room. The entire upper floor was occupied by a bedroom or dormitory. In the early 13th century, the eastern wing was extended by 12 meters to the north, enlarging the dormitory and connecting it with the latrine block. The chapter house was also enlarged to the east. In the northern wing, parallel to the church nave, were located the kitchen and the refectory, where the monks ate their meals. To the west, the inner courtyard was enclosed by a third wing containing the lay brothers’ quarters. The ground floor rooms were connected by a cloister, which in the 13th century consisted of at least three arms: northern, eastern, and southern. The western arm of the cloister may have been missing at that time, as the adjacent wing of the claustrum stood at some distance from the nave of the Romanesque church. It is possible that the western wing, occupied by the lay brothers, was separated from the rest of the claustrum by a sort of alley.

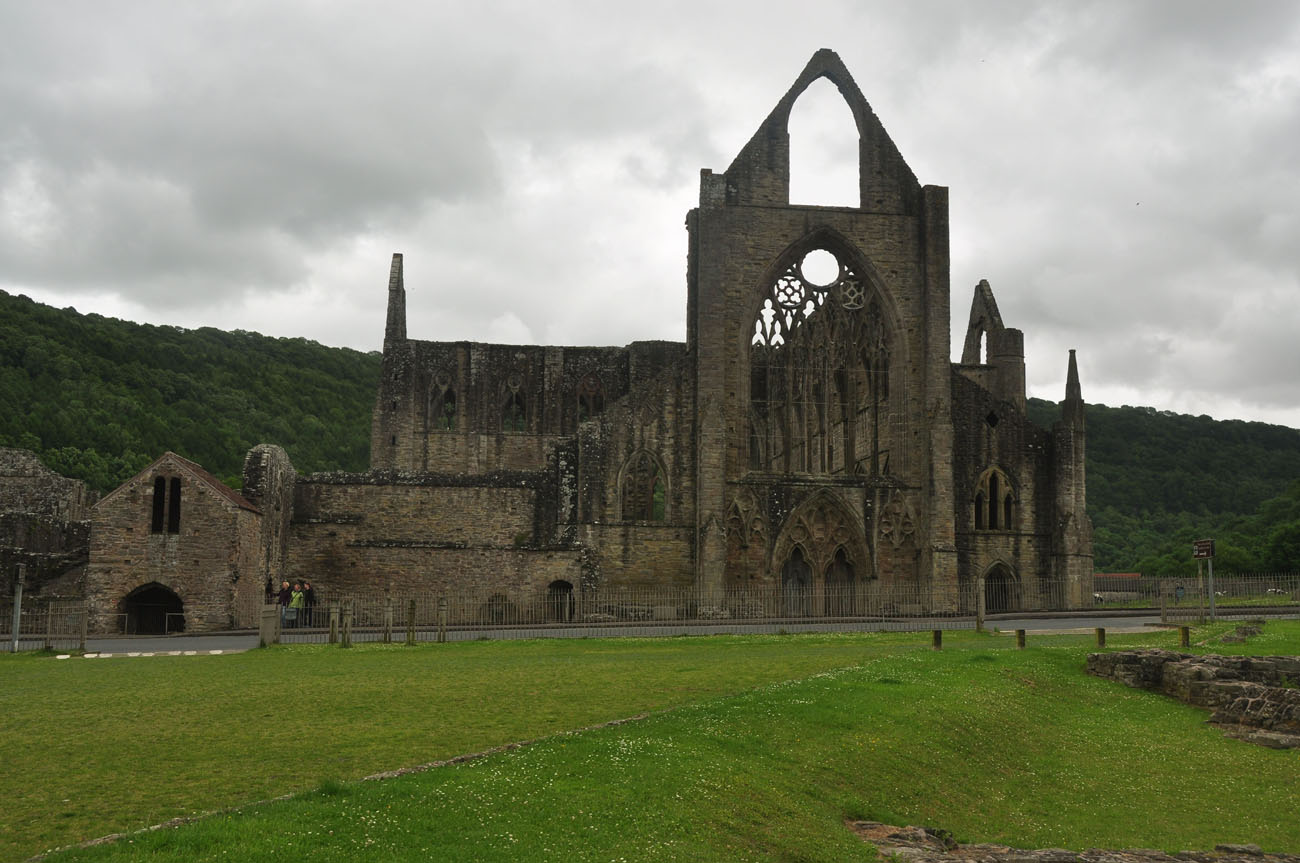

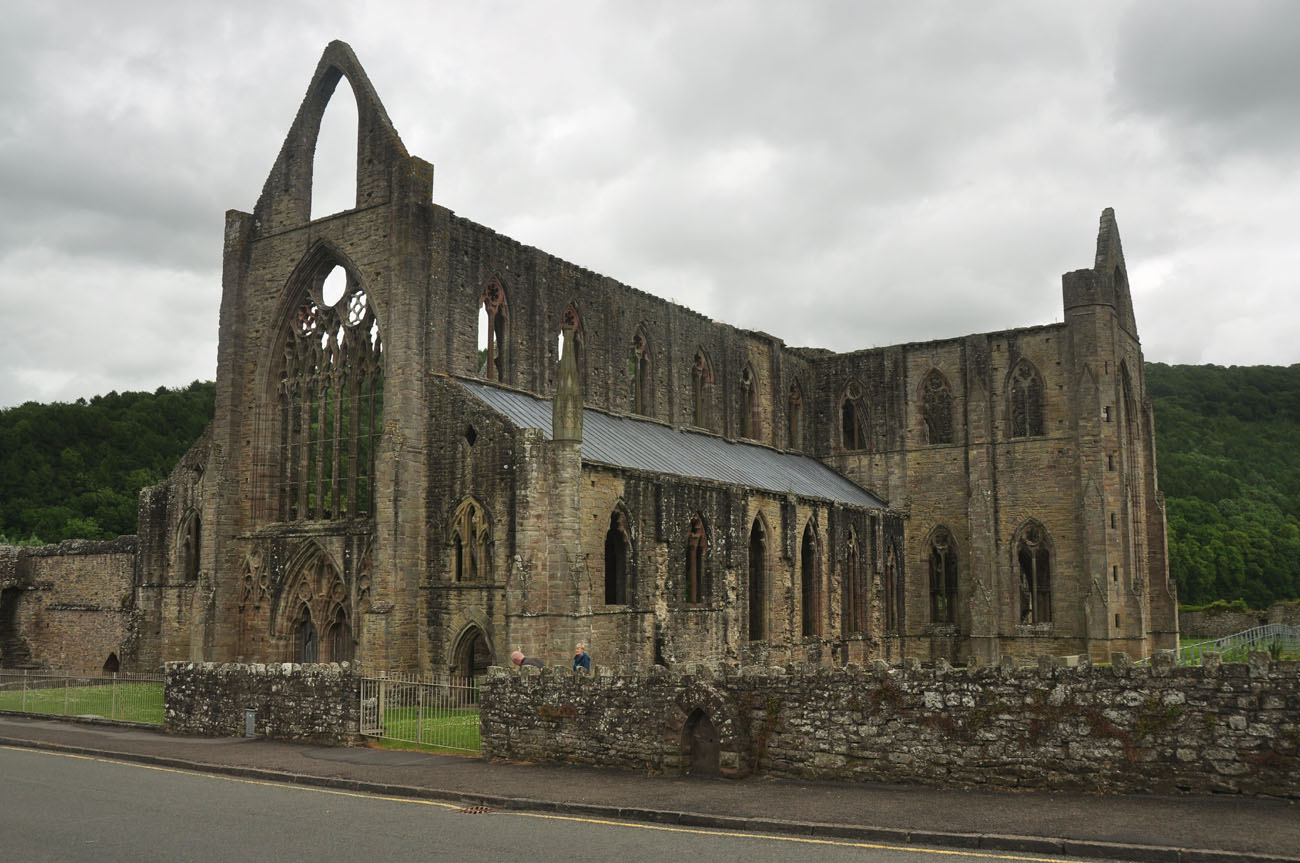

The monastery church from the second half of the 13th century, was begun on the southern side of the older structure to ensure its longevity, although its grounds were ultimately completely absorbed by the more monumental work. The new church was built in the English Decorated Gothic style, abandoning the Cistercian simplicity of the earlier church. It was a basilica on a Latin cross plan, consisting of a six-bay aisled nave, northern and southern transepts, and a rectangular, aisled chancel. In the eastern part of the latter, there was a row of chapels, but these were not architecturally distinguished from the exterior. As in a Romanesque church, the Gothic transept had two chapels placed at the eastern walls of each arm. The church did not have a large tower, only a small steeple at the crossing. Construction began in the chancel, moving towards the transept and nave. The entire building ultimately reached an impressive length of 72 meters. Compared to the older church, it was not only longer but also taller, with a slenderer form and a much lighter structure.

From the exterior, the church walls were supported by numerous buttresses, placed perpendicularly at the corners. In increasingly higher sections, thanks to offsets topped with small gable roofs, the buttresses were built shallower, and as a result, in the upper sections it had the form of pilasters. The walls of the nave and chancel were also reinforced with pilasters disappearing into the roofs of the aisles. A foresight was demonstrated by the exceptional use of two flying buttresses in the northern transept, transferring the weight from its high walls to the lower buttresses at the side chapel walls. At the base, the church walls were framed by a plinth with a moulded cornice, which also encompassed the buttresses. At the crown, the walls likely terminated in a simple parapet, supported by rows of corbels. A cornice under the windows also provided a horizontal accent to the exterior facades, which encompassed the buttresses as did the plinth cornice. Shorter sections of cornice separated the church’s triangular gables in both arms of the transept and the central nave and chancel.

The church was lit by pointed-arch windows placed between buttresses and pilasters. To the north and south, these were predominantly large, moulded windows with two-light tracery, while the two western bays of the southern aisle featured smaller windows with higher sills, likely due to their construction in the second phase of the church’s building. The change in plan was also evident internally, where the clerestory windows of the nave were framed by free-standing columns in the earlier phase, and in the western bays by roller-shaped moulding in the later phase. The windows of the northern aisle were lower than the others, but this time not due to the change in plan, but because of the cloister built beneath them. The eastern and western aisle windows, on the other hand, were slightly wider and three-light. The most impressive windows, filling almost the entire space between the buttresses and cornices, illuminated the church from the east and west along the axis of the nave. A slightly narrower window was set in the south wall of the transept, cut at the bottom by the triangular portal gable. The large six-light north transept window was halved to accommodate the east wing’s roof, but, as in every other gable wall, another window was placed above it, illuminating the church’s attic. The windows featured a variety of stone tracery patterns, the most magnificent of which was installed in the large eight-light window on the east wall of the chancel and the seven-light window on the west façade. In both, the tracery formed classical geometric patterns popular in the late 13th century, divided by slender mullions into lancets with trefoil heads, above which were round rosettes with further trefoils, cinquefoils, and hexafoils.

The main entrance to the church was located on the axis of the central nave from the west. Like the large seven-light west window and the large five-light window in the west gable, it was intended to impress visitors. Two trefoil-topped openings with moulded jambs were created, framed by a common pointed arch of a large archivolt. The archivolt’s surface was decorated with handsome blind tracery with a background covered with delicately carved geometric motifs, and the moulded arms of the archivolt were set on free-standing columns. In the center was an almond-shaped niche, originally housing a carved figure of St. Mary, flanked by two circles with hexafoil rosettes, inscribed in successive pointed arches. Similar figures likely also appeared between the blind tracery to the right and left of the entrance. From 1320, the main portal of the church was preceded by a porch, whose arcades supported by four columns and vault likely protected a statue, which attracted numerous pilgrims. It could be bypassed by the western portal, leading directly to the southern aisle. It was closed with a pointed arch, with a moulded archivolt set on a pair of free-standing columns. The stepped, pointed southern portal of the transept was framed by three pairs of columns. This served as a side entrance to the cemetery (Latin: Porta Mortuorum) located on the eastern side.

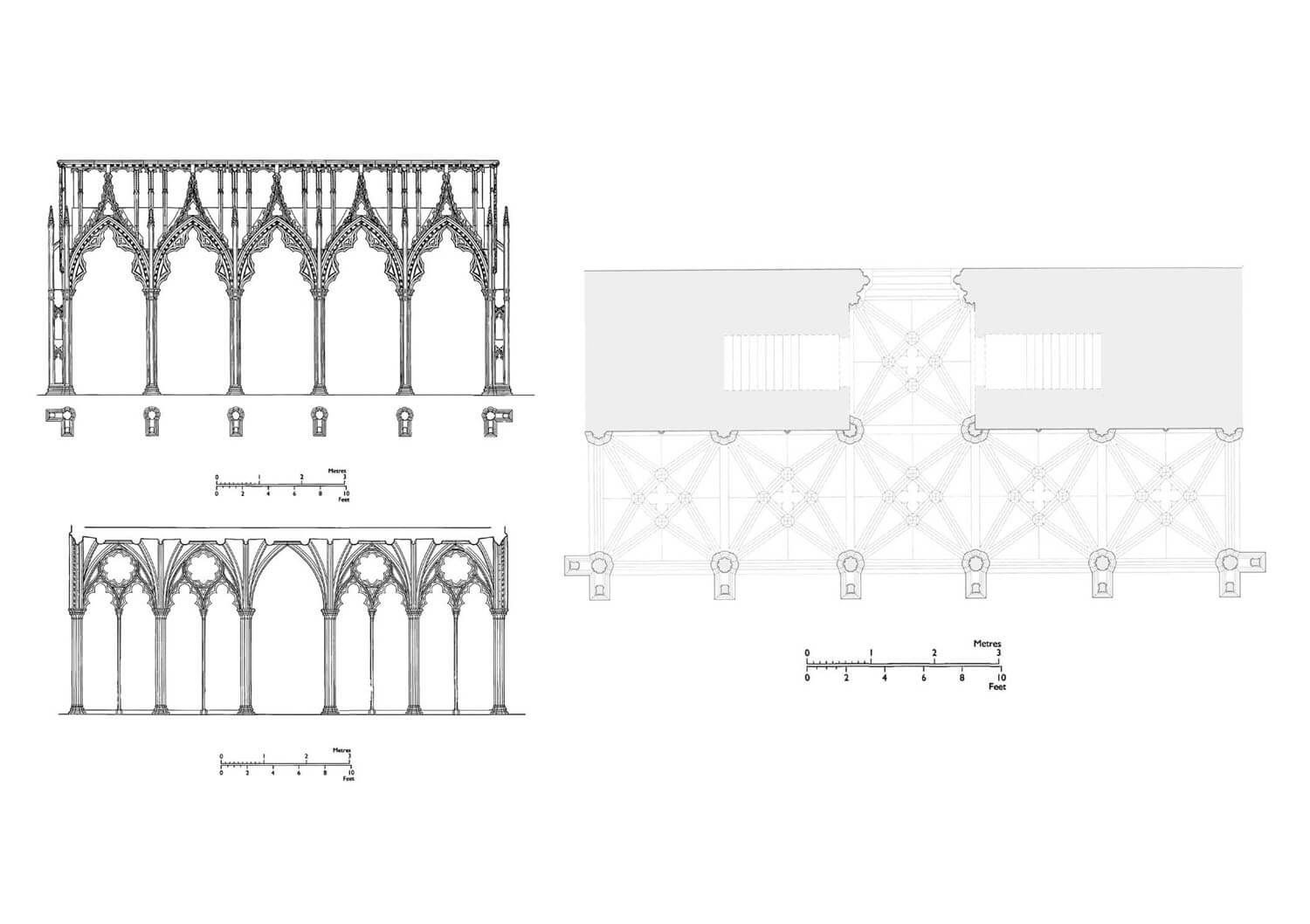

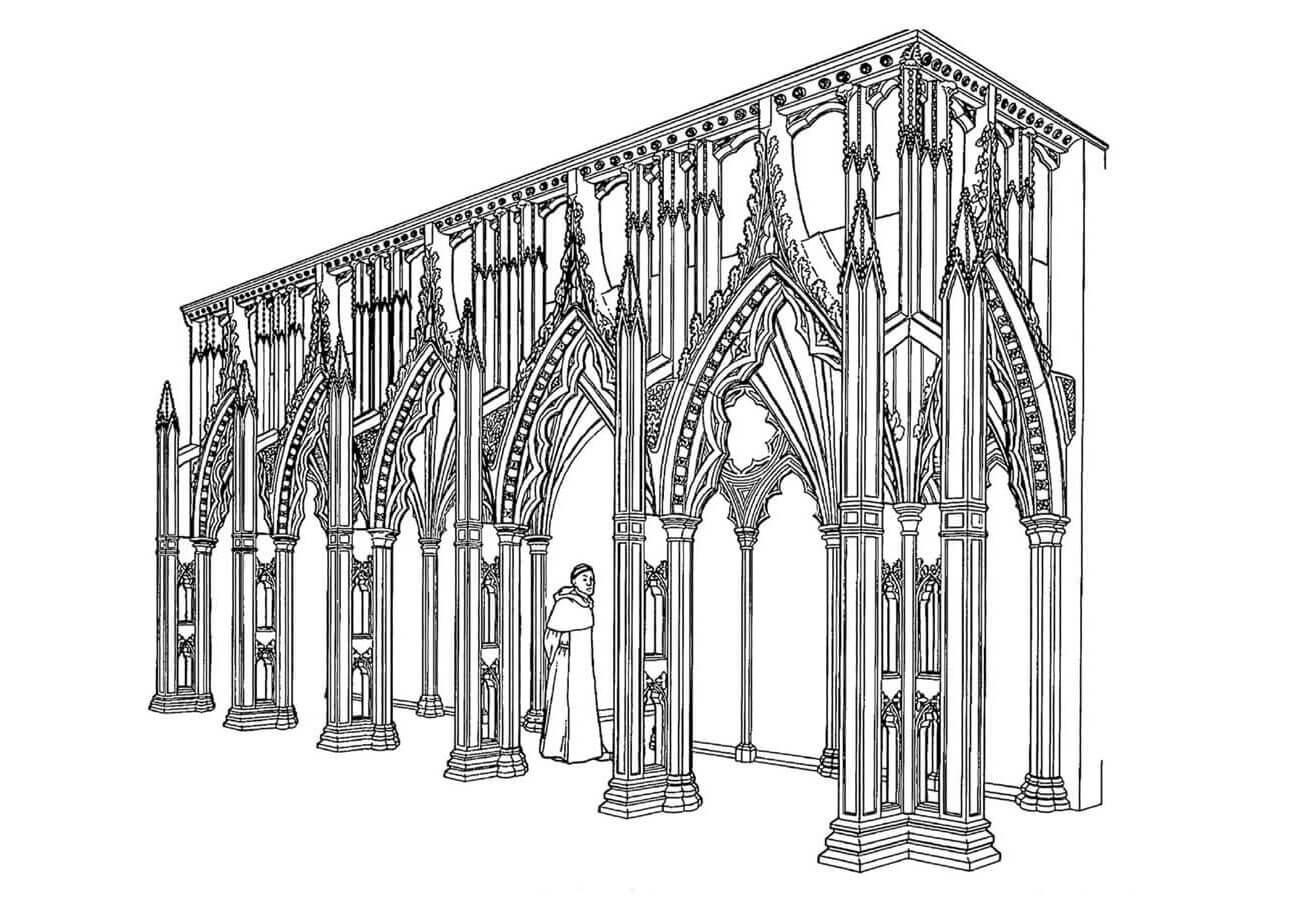

The nave of the church was divided into six bays, separated by eight-rolled pillars that supported pointed arcades. Despite the church’s large size, the interior was not dominated by open space, as the aisles were separated from the central nave by a 3.4-meter-high wall, stretching between the pillars. Additionally, in 1330, a magnificent stone rood screen was placed between the fourth and fifth pairs of pillars of the central nave, separating the section of the church reserved for lay people from the section accessible only to the monks. It was a five-bay structure, pierced to the west by richly decorated pointed arcades with floral ornamentation, morphing into ogee arches, and topped with a frieze at a height of 5.5 meters. Each western arcade was flanked by a separate pinnacle (with additional ones placed to the north and south), connected to the rood screen pillars by a pair of “bridges.” At the central bay, the rood screen had an additional eastern bay, flanked to the north and south by stairs leading to the upper loft.

The longitudinal walls of the church’s nave consisted of three levels, separated by cornices. The lowest consisted of pointed, richly moulded arcades. Above this stood the triforium, which in Tintern constituted a solid wall with a flat, undivided surface—the only expression of Cistercian austerity in the church. Above this was the clerestory, with the nave windows divided by ribs springing from overhanging shafts, mounted on bas-relief corbels, nestled tightly between the archivolts of the inter-nave arcades. In the transept, the chapels were opened with high arcades similar to those in the rest of the church, but in the northern arm and in the western wall of the southern arm, at the level of the triforium, a gallery ran through the thickness of the wall. Its construction necessitated the creation of large pointed-arch recesses, the upper sections of which also contained windows. In the northern wall, the gallery was concealed behind the lower section of a six-light window, half-blocked from the outside. It cleverly opened towards the church with six arcades with trefoil heads, created as part of the window tracery. The walls of the chancel were divided similar to those in the nave, with three sections: an arcades, a triforium, and a clerestory.

Around the choir in the central part of the church, four massive pillars supported intersecting arcades and rib vaults. In this area, just behind the rood screen, stood wooden stalls, or seats for the monks. Further inside the three bays of the chancel was the altar, around which the side aisles provided an ambulatory for processions. The pillars dividing the chancel space were framed by four corner shafts, four fewer than in the nave, although the arcades in the eastern part of the church were more elaborately moulded than in the later western part. In the last bay of the southern aisle, a niche with a piscina was located, used for washing liturgical vessels. The entire interior of the church was plastered and whitewashed, with red paint imitating stone blocks. More elaborate wall murals were likely created in some chapels towards the end of the Middle Ages. The floors in the most important parts of the church, namely the chancel, choir, and transept, were covered with clay tiles featuring over 30 patterns: heraldic, geometric, and floral. Stone cross-rib vaults were installed throughout the entire structure, in the nave and chancel springing from the aforementioned triple shafts, supported by corbels with carved floral motifs.

Access to the church from the cloister was via the so-called night stairs in the north transept, which led to the dormitory and were used during night services. Next to them, a lower portal led to the sacristy, and in the western part of the north aisle of the chancel, a portal was opened in the 14th century, leading to a long covered corridor to the infirmary. Another richly moulded and decorated portal connected the eastern part of the north aisle of the nave with the cloister. This was the main daily entrance for monks on their way to services, and therefore had a particularly ornate form, since the late 13th century onwards with an inner octafoil archivolt, the central part of the frame decorated with a pattern of intricately carved flowers, and an outer archivolt flowing into similarly moulded jambs. The whole was topped by a triangular gable with a large trefoil blind tracery. For the lay brothers, a much simpler portal was created, connecting with the west wing, unusually opened at an angle in the corner of the nave. Vertical circulation within the church was provided by a spiral staircase, located in the corner of the southern transept, leading to a gallery in the western wall and then to the attic adjacent to the southern aisle. A similar staircase led to the northern gallery of the church, but it was located on the first floor of the dormitory adjacent to the northern transept.

The monastery claustrum buildings, even after the 13th-century expansion, were located on the north side of the church. Initially, a rectangular garth of moderate dimensions adjoined the northern aisle, originally surrounded by Romanesque cloisters. After a mid-13th-century reconstruction, it was enlarged to an almost square size of 30.5 x 33.5 meters, thanks to an extension along the north-south line while maintaining the original east-west width. The cloisters provided access to most of the buildings without having to exit into inclement weather. It also provided space for study, relaxation, contemplation, and certain ceremonies. It were covered with lean-to roofs, supported from the mid-13th century by two rows of columns topped with semicircular arcades filled with elegant, variously moulded trefoils. The arcades were connected by miniature ribbed vaults, and the alternating arrangement of the columns was also a novelty.

In the second half of the 15th century, the southern and western sections of the cloister were rebuilt. These sections were likely vaulted, and after the external walls were reinforced, windows were installed to protect against harsh weather conditions. The southern arm of the cloister was distinguished by a continuous stone bench against the church wall (also created along part of the eastern arm of the cloister), in the center of which was a pointed niche. The abbot would sit in this alcove, listening to the reading before the procession to the church for compline. Two further semicircular niches in the cloister wall were added as early as the 13th century on the eastern side, in the transept wall, where bookshelves with doors were likely located. One of these was bricked up during the 15th-century reconstruction of the cloister.

On the western side of the cloister was a 13th-century wing, serving as the main entrance to the claustrum. In the northern part, this section housed the lay brothers’ vaulted refectory, lit by narrow windows with trefoil heads. It was connected to the rest of the buildings relatively late, only at the end of the 13th century, when a diagonal passageway to the cloister was constructed. The western wing also housed the parlour, a room for contact with laypeople, where the rule of silence was not observed. In front of this, at the end of the 13th century, a vestibule was added, where guests arrived, for whom a stone seat and a large niche were provided. In the 15th century, likely to enhance splendor, the entrance door from the vestibule to the reception area was rebuilt and a stone vault was installed. North of the parlour was a square, vaulted room with no direct connection to the cloister. It was used as a storeroom and a cellarium. The upper floor of the west wing housed the chambers of the monk in charge of the cellarium, where he conducted business, received guests, and managed the monastery’s property. In addition, the northern part of the upper floor must have been occupied by the lay brothers’ dormitory. In the 14th century, the west wing was extended southward, allowing to be connected by a direct, diagonal passage to the north aisle of the church.

The western corner of the north wing housed the monastery kitchen. It was located precisely between the aforementioned lay brothers’ refectory and the monks’ main refectory, located to its east, allowing to efficiently serve both wings. The kitchen’s interior was divided into two rooms. The eastern one contained a chute for waste disposed of into the gutter, an opening in the wall to facilitate the transfer of dishes to the main refectory, and a connection to the cloister. The western room contained a fireplace and three doors: to the cloister, to the western wing, and to the rear courtyard. The southwest corner of the kitchen was rebuilt in the late 13th century, when a diagonal passage from the cloister to the western wing was built through the thickness of its wall.

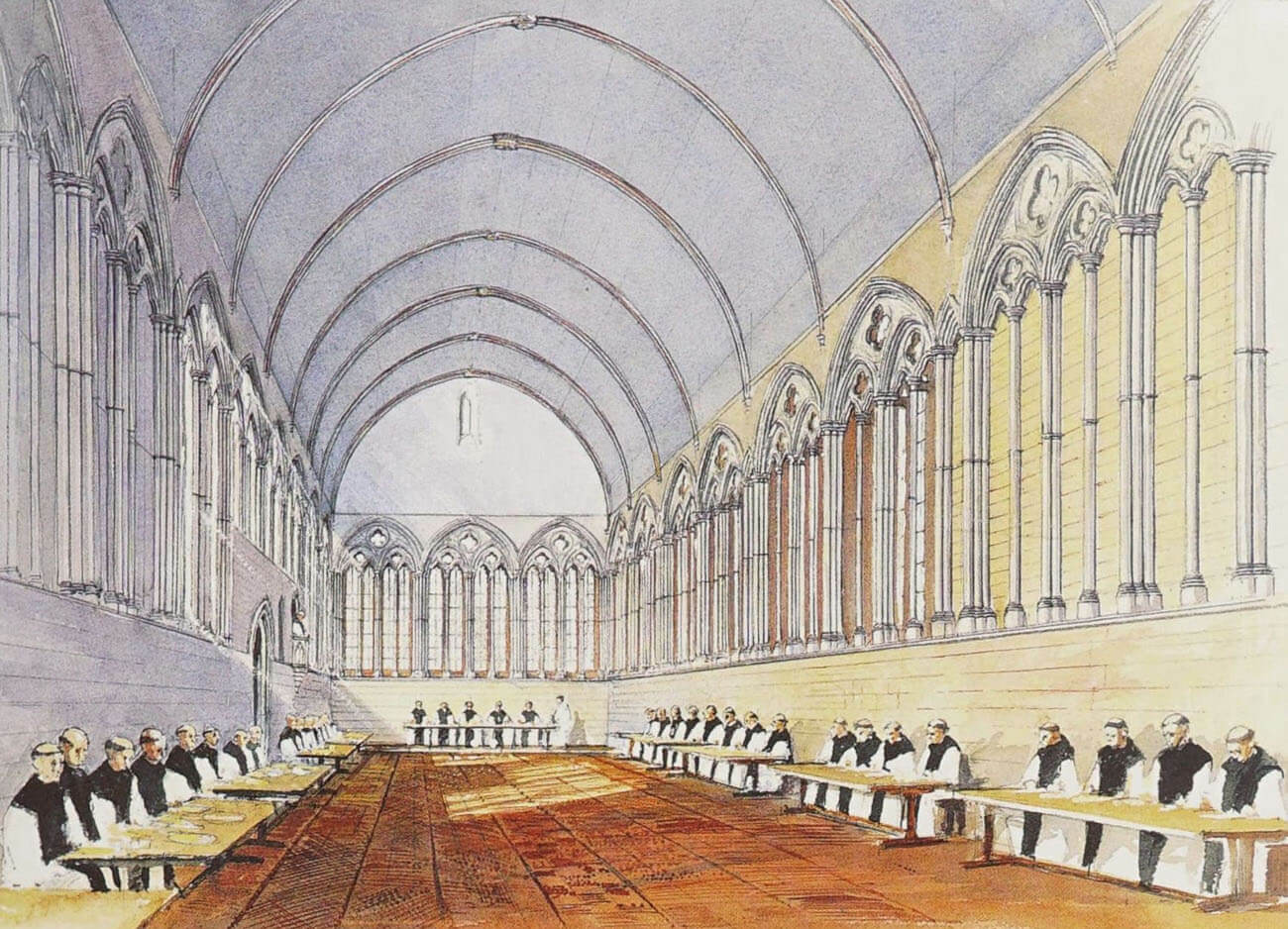

The main refectory, or monks’ dining hall, was a large rectangular building after reconstruction in the first half of the 13th century, with longer walls running north-south, in typical Cistercian fashion, with the longer axis perpendicular to the wing axis. It was an impressive hall, 26 meters long and 9 meters wide, likely topped by a timber open roof truss or wagon roof. It was lit by tall, four-light windows, with two pairs of narrow openings closed by trefoils and topped by oculi. Two such windows were placed between pairs of buttresses on the east and west sides, and three more were inserted on the north side. The windows were framed on the inside by slender columns, with the same division applied to the two windowless southern bays, where the recesses were filled with columns and blind tracery. Inside the refectory, the monks gathered only once a day for a silent meal. After its completion, two niches with trefoil-shaped heads, located in the southern wall, were used for washing and storing dishes. On the other side of the portal was a rectangular niche, perhaps intended for a retractable seat, and an opening connected to the kitchen. Furthermore, a staircase in the thickness of the western wall led to a pulpit from which readings were read during meals. On the southeast side, the portal led directly to a small pantry or storeroom. The entrance to the refectory from the cloister side likely featured a handsome portal with numerous shafts or columns on the sides, flanked by wide and narrow pointed arches for washbasins, all enclosed by groups of shafts.

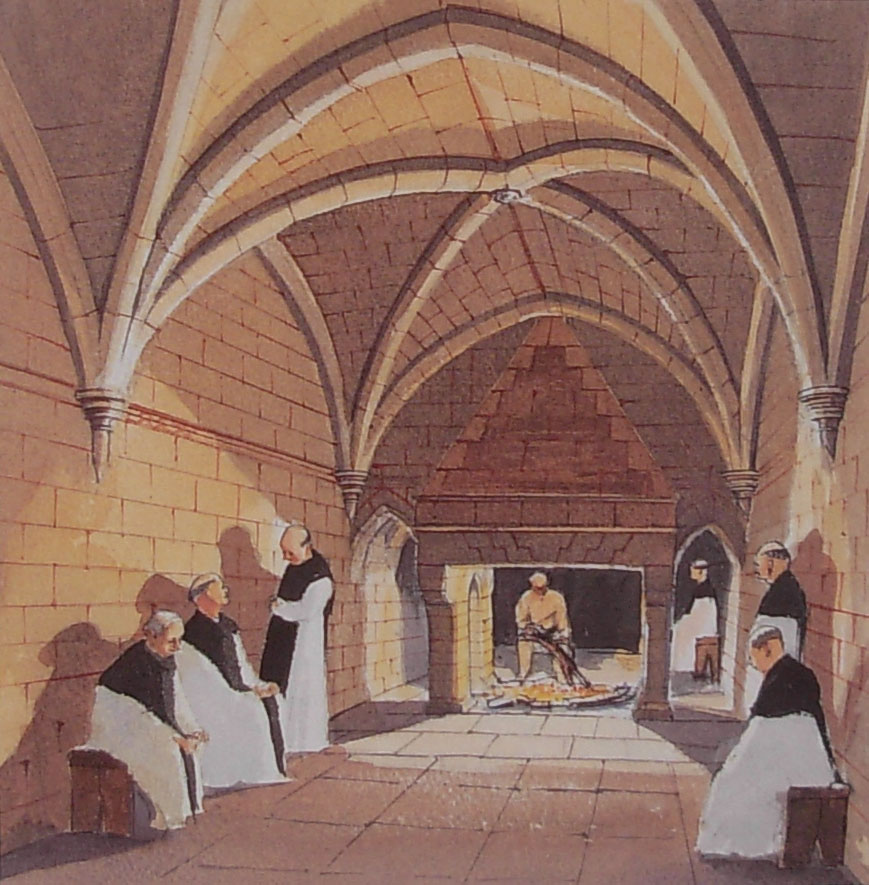

On the eastern side of the refectory was a much smaller, rectangular building with a calefactory on the ground floor, covered by a two-bay cross-rib vault. This was the only permanently heated room in the abbey, besides the kitchen and infirmary, also used for bloodletting, as prescribed by contemporary medicine. In its center, a fireplace supported by four pillars stood, allowing to access the fire from all directions by narrow passages along the sides. The upper floor likely housed a small, vaulted archive, where the monastery’s most important documents were kept dry. Next to it, on the first floor to the east, was a larger room, lit from the cloister by three small lancet windows and two windows on the north side. The space on the eastern side of the warming room was filled by a passageway with a so-called day stairs, leading to the dormitory and archives. A portal at the ground floor also led to the rear courtyard, where wood for the fireplace may have been stored. Near the very end of the monastery’s existence, a second floor was added, likely for residential purposes. This was lit by late Gothic Tudor-style windows.

The northeastern corner of the cloister was occupied by a large rectangular building of the east wing. This was one of the oldest stone structures in the monastery, extended northward by three bays around 1200 and supported by several buttresses. Most of the ground floor was then occupied by the day room, covered by a vault supported by a row of five octagonal columns and moulded corbels set into the walls. It was lit by tall, narrow windows with chamfered frames on the outside and deep splays on the inside. Initially, these windows had circular heads, but were modified to lancet ones in the western wall and the southern part of the eastern wall later in the 13th century. To the east, the day room had a two-story annex with latrines and a chute for waste disposal. The ground floor contained two vaulted rooms with a passage to the infirmary, while the upper floor provided access from the dormitory to the latrines located above the chute. A canal with clean water also ran beneath the day room in the northern part of the building. Its level could be raised using sluices, then redirected to the north-east canal above, towards the abbot’s residence. This water source was so important that fines were imposed on monks who washed in it or polluted it.

The upper floor of the eastern wing housed the monks’ 52-meter-long dormitory, which led to the church’s north transept and to the aforementioned latrines. Such a large room could accommodate up to one hundred straw mattresses. In the later Middle Ages, when the number of monks declined, the dormitory was likely divided by wooden screens to provide the brothers with greater privacy. On the ground floor on the south side of the day room, east wing housed a passage leading to a second cloister and another narrow room, originally containing the stairs to the first floor. Further along was a narrow, rectangular room, the parlour, where the brothers could converse briefly during the day without breaking the monastic rule. This room was lit only by a single window on the eastern side.

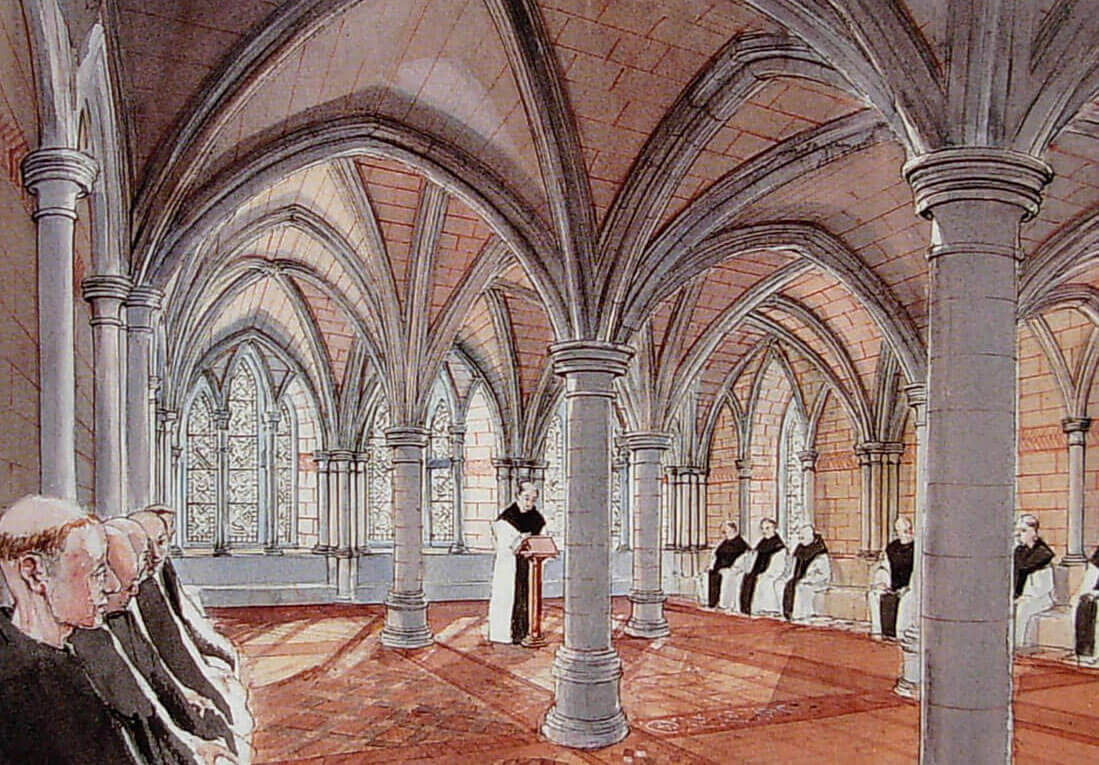

Between the northern arm of the church’s transept and the day room were a small sacristy and a much larger chapter house. The chapter house was entered from the cloister through three richly decorated arcades, supported by pillars clasped with a total of 14 shafts, six of which were not permanently attached. A rib vault was supported by eight pillars, dividing the space into three aisles. All pillars had circular bases, but with various moulding. The three western bays of the chapter house, located directly beneath the dormitory, were converted into a vestibule in the later Middle Ages, while the two eastern bays, which had higher vault and a decorative tile floor, constituted the chapter house proper. It was lit by three large pointed windows in the eastern wall. Inside, on stone benches placed along the walls, the monks, led by the abbot, gathered to listen readings from the monastic rule and to discuss the monastery’s daily problems and affairs. Individual and grouped wall-shafts rested on the benches, featuring moulded capitals similar in form to the pillar capitals.

The southern two rooms of the east wing, covered with cross-rib vaults and lit from the east by a five-light window with a segmental head, were occupied by the sacristy and a small library (armarium). Access to these rooms was from the west, through a stately portal, a somewhat simpler version of the church’s main western entrance. It consisted of two lancet-shaped openings filled with tracery, framed by a common pointed archivolt with continuous moulding above a low plinth. Additionally, a circular window, also originally filled with tracery, was placed between the lancet openings. Inside, the sacristy vault rested on semicircular corbels, and a stone cabinet filled a recess in the south wall. The floor of both rooms was paved with tiles. Above, a door in the south wall of the dormitory led to the treasury.

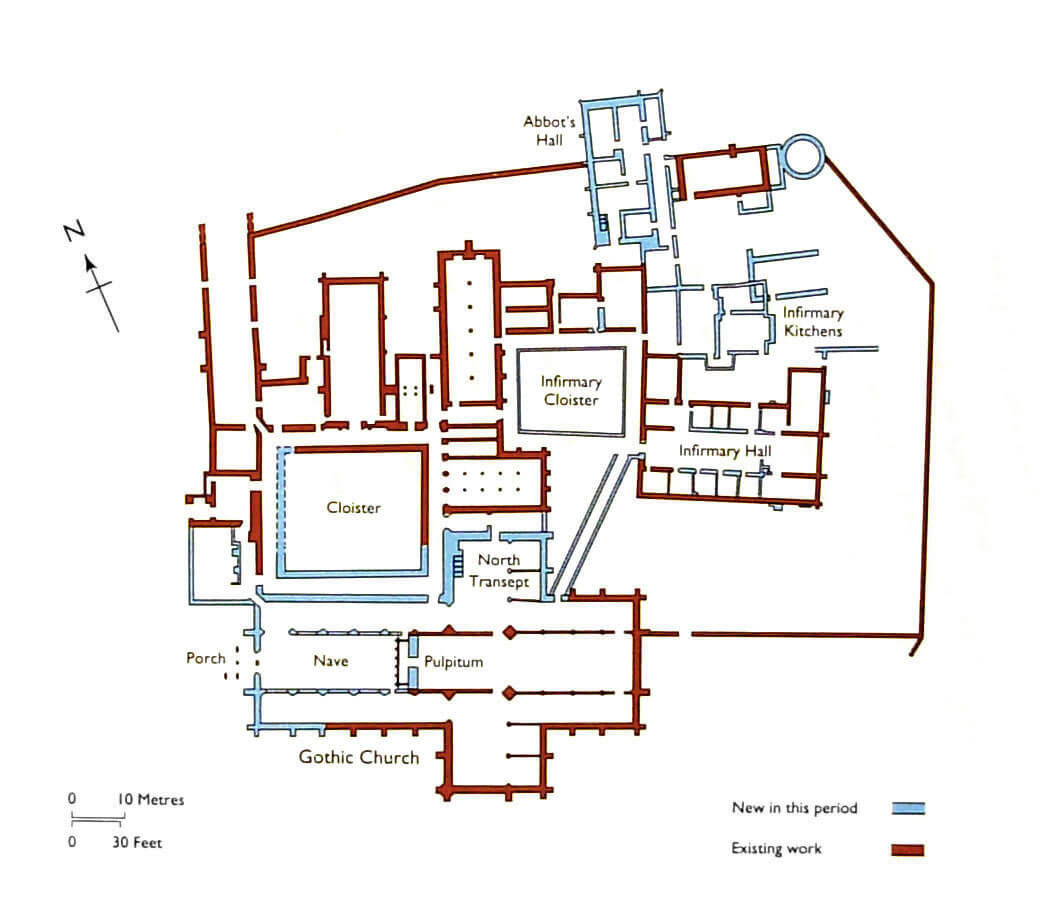

To the north of the church’s chancel was a second cloister garth, also known as the infirmary cloister. Its ground plan measured 25.6 x 21.6 meters. Since the 14th century, a covered passage led directly from the church to this cloister. Immediately adjacent to it, on the eastern side, was the infirmary building, a basilica-like structure measuring 33 x 16 meters, with clerestory windows above the side aisles, two projecting annexes to the north, buttresses to the east, and a chamfered plinth. This building was reserved for the sick and elderly monks, so it had to be built somewhat out of the way. Internally, it was divided by five-bay arcades on rhomboid pillars with shafts at the corners. From the 15th century, the aisles were divided by wooden partitions, creating separate cells heated by fireplaces. A larger room on the northeast side, also heated by a fireplace, may have housed the brother in charge of the infirmary. A separate annex on the northwest side housed latrines, situated above the sewage channel. These adjoined the infirmary kitchen complex, which was built only in the 15th century, though it may have replaced an earlier structure. A hearth within it provided meals for both the sick and the residents of the abbot’s quarters. Later in the 15th century, the kitchen was expanded on the eastern side by two additional rooms, connected by a passage in the southern annex. Two more hearths and a scullery were located within these rooms.

The abbot’s house, rectangular in plan and originally freestanding, was built in the first half of the 13th century in the northeasternmost part of the monastery. This building served as a reception space for the superior of the abbey to receive guests and benefactors. Initially, the abbot lived with other monks, but by the 13th century, he had two private, separate rooms next to the infirmary cloister, arranged in an L-shape. The smaller of these rooms, the western one, was heated by a fireplace. At first floor level, they could have been connected to the latrine block and further on, to the brothers’ dormitory, but in the 14th century, a passage was created between the latrines and the abbot’s house. In the 14th century, as the monastery’s importance and the abbot’s rank grew, along with a desire for greater comfort, a completely new building was constructed on the north side, connecting the two previously described buildings (a free-standing one and an L-shaped one). This was a spacious structure with numerous rooms and a long entrance hall facing the river. Its connection to the infirmary kitchen also ensured the rapid serving of meals. During this period, a chapel with a piscina in the wall and a two-light window on the eastern side was added to the 13th-century abbot’s building on the south side. Right next to it, an annex with a latrine and a dovecote of uncertain date were built.

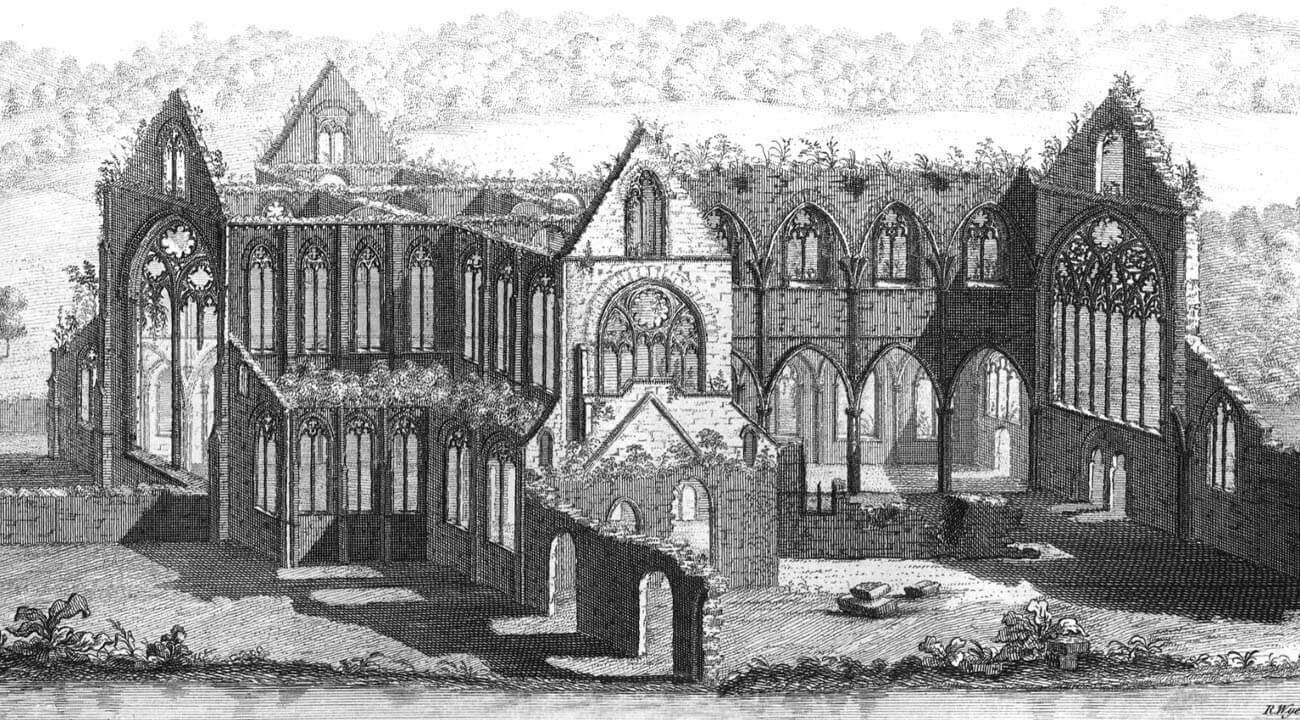

Current state

Church of Tintern Abbey, despite being a ruin, is today one of the best-preserved monastic religious buildings in Wales, and also one of the most picturesque. Moreover, it is an outstanding example of 13th-century English Decorated Gothic. The south aisle is the only roofed part of the church today. Unfortunately, the north wall of the nave, along with its arcades, has not survived, and much of the architectural detail has been destroyed or lost. Little of the extensive complex of claustrum buildings has survived. Only the eastern section of the north wing with warming room and archive remain, and the northern and southern sections of the east wing, with the walls of the day room and the partially vaulted sacristy. The once-impressive refectory retains windows only in the eastern wall. The adjacent kitchen has undergone almost complete decay, while the walls of the west wing and vestibule have partially survived. Of the remaining buildings, only the foundations and lower sections of the walls are visible. Among these, the chapel of the abbot’s residence, located on the edge of the complex, stands out with its higher-preserved walls.

The historic building is open from March 1st to June 30th, daily from 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM; from July 1st to August 31st, daily from 9:30 AM to 6:00 PM; from September 1st to October 31st, daily from 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM; and from November 1st to March 31st, Monday through Saturday from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM, and on Sundays from 11:00 AM to 4:00 PM. Please note that the last visitors are traditionally admitted half an hour before closing time.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Harrison S., Morris R., Robinson D.M., A Fourteenth Century Pulpitum Screen at Tintern Abbey, Monmouthshire, “The Antiquaries Journal “, vol. 78 , 1998.

Harrison S., Robinson D.M., Cistercian Cloisters in England and Wales Part I: Essay, “Journal of the British Archaeological Association”, 159 (2006).

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Robinson D.M., Tintern Abbey, Cardiff 2002.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.