History

The construction of the stone walls at Tenby probably began in the first half of the 13th century, at the initiative of the earls of Pembroke, the Marshal family. It certainly replaced earlier timber and earth fortifications from the 12th century, probably built after the town was burned in 1187 by Welsh forces led by Maelgwn ap Rhys. The construction of the stone fortifications was probably carried out by local effort, with the first stage, resulting in a low and towerless wall, taking at least five years. Repairs to the fortifications must have been carried out in the time of William de Valence, the first Earl of Pembroke, after the town was sacked in 1260 by the Welsh Prince Llewelyn ap Gruffydd.

In 1328, the first seven-year murage grant related to work on the walls of Tenby was recorded in documents. The king set out the fees to be levied on various goods imported into the town, and used to build the quayside and complete the perimeter wall. However, these were small sums, and construction works could not be undertaken on a large scale. The townspeople were clearly much more concerned about meeting the costs of building the quayside, as ten further charters were issued for this purpose between 1344 and 1431. This suggests that by the mid-14th century the town’s defences were considered adequate to meet the threats then foreseen.

In the mid-15th century, Jasper Tudor, Duke of Bedford and Earl of Pembroke, at the request of the mayor and townspeople, ordered a major repair and modernisation of Tenby’s town walls. It were raised and widened to allow for faster movement of defenders. In addition, Jasper Tudor granted the fortifications to the tenants of Tenby and allowed the proceeds of fines for penalties to be used for future repairs to the walls. In 1484 King Richard III issued a further charter to support the construction of the walls, so work on their reinforcement must have been ongoing.

Early modern repairs to the fortifications were carried out in 1588, as evidenced by a plaque commemorating mayor Howell Howells. This work was certainly carried out because of the threat of the Spanish Armada, and was therefore carried out hastily and carelessly. The renovated section to the south of the west gate was built much thinner than the rest of the curtain wall and was not provided with a series of loopholes or hoarding holes. Moreover, it was so poorly constructed that it partially collapsed before the early 19th century, while the older but more solid adjacent sections of wall stood the test of time.

The town, and with it the fortifications, had been in a state of decay since the 17th century civil war, with the sieges of Tenby in 1644 and 1648 contributing particularly to its destruction. The demolition of the fortifications, and particularly the town gates, began in the late 18th century to accommodate the increasing traffic. The Great Gate, damaged in 1708, was completely demolished in 1781. In 1867 and for several years thereafter, the local town council proposed demolishing of the barbican of the western gate, but fortunately this was prevented by the actions of historical societies and scholars. The threat was completely removed when the local advocate, Dr. George Chater, obtained a court order halting all demolition.

Architecture

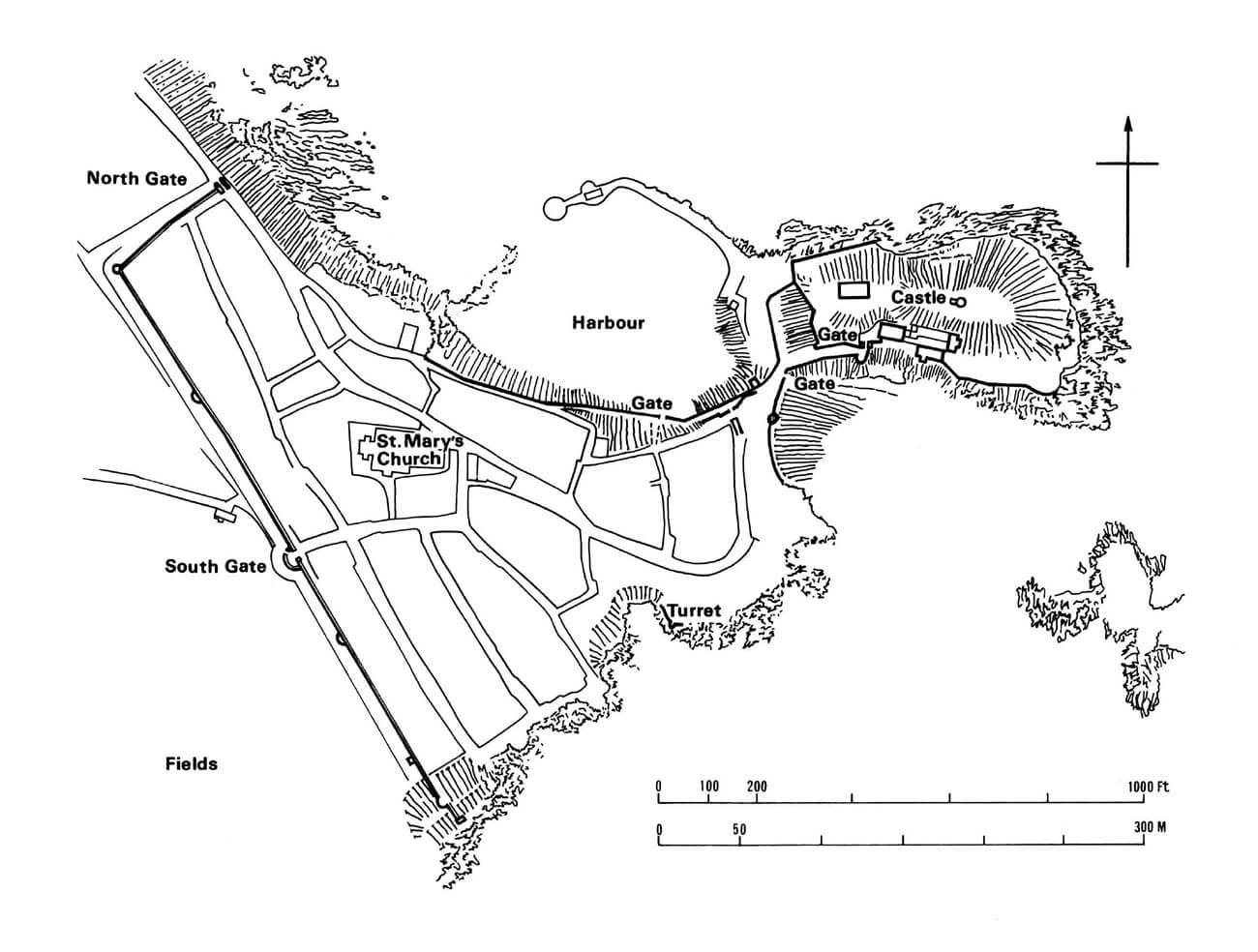

Tenby was founded on a plan similar to a triangle, filling the headland jutting into Carmarthen Bay (Welsh: Bae Caerfyrddin), with an extension eastwards towards the castle, which was located at the very tip of the peninsula, just beyond its narrowing. From the north, the town was protected by sea cliffs, and similarly to the south it bordered the coast, so the town walls were not necessary along the full circumference. Towards the land on the west side, a long and straight section of fortifications was directed, which, as the most endangered, was fortified first and most strongly. The ground level in the town gradually dropped from north-east to south-west. Its central part was occupied by the parish church, which at the end of the Middle Ages filled the vast area between the port and the main line of fortifications. The street network in the lower part of the town was relatively symmetrical, but it is not known whether there was a wide underwall street. Probably only a narrow strip of undeveloped space was left between the wall and the townspeople’s plots.

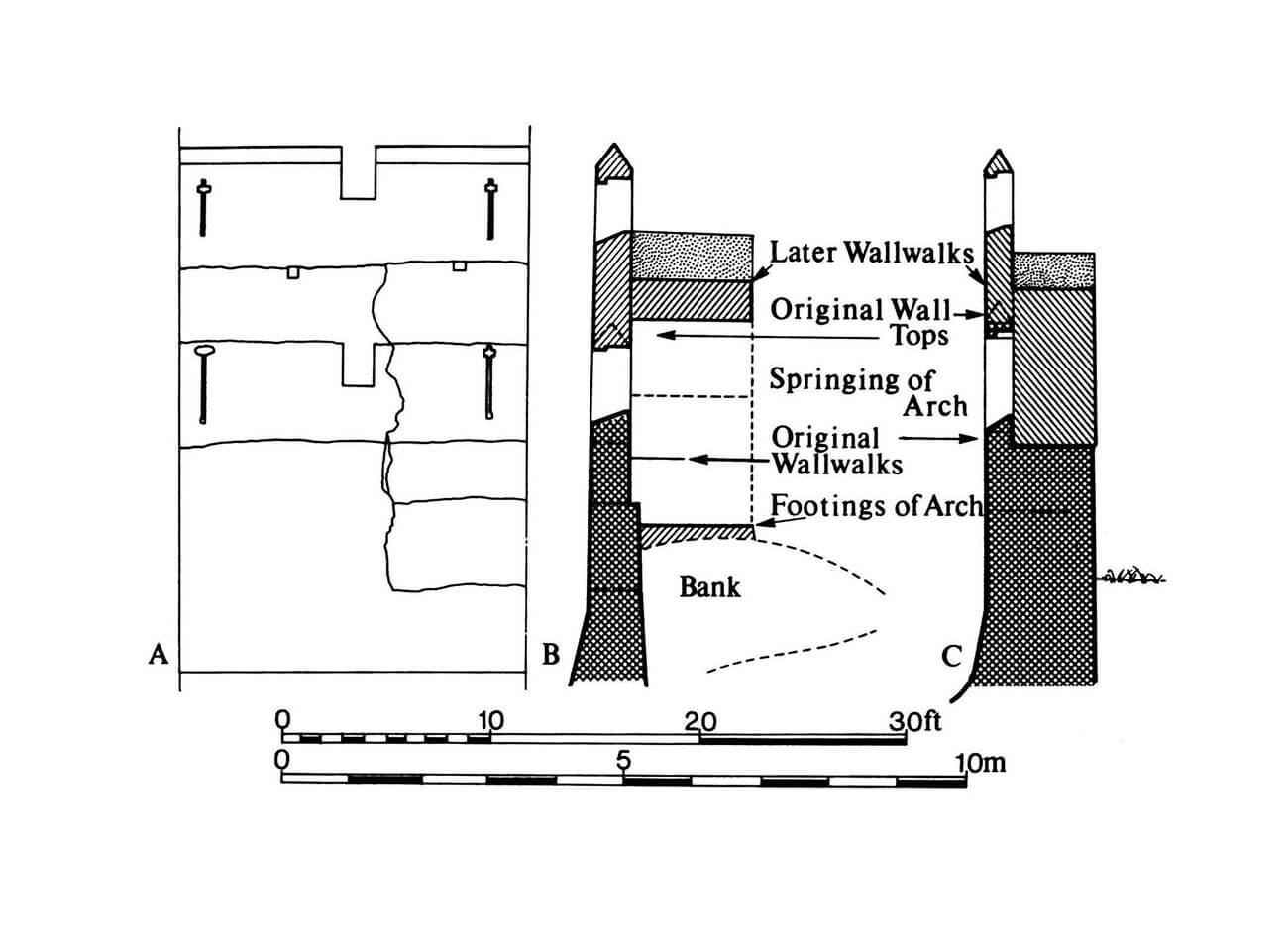

The town wall was built of local, roughly worked on the face side stone. Initially, in the first half of the 13th century, it was only 1.1 meters thick at the ground level and 0.8 meters above the batter part with externally sloping elevations. Moreover, in the upper part, at a height of about 2.4 meters, due to the offset from the inside, it narrowed to about 0.5 meters. From the foreground, it was probably preceded by a ditch, without which it would not have been too much of an obstacle. The long western section of the fortifications had this form, while the short north-western section, connecting with the seaside cliffs, was distinguished by a much greater massiveness of the wall. It was 1.6 meters thick at the base along its entire height, up to the walk in the crown. This may have been due to the weaker earthen fortifications in this section or even the complete lack of a ditch on the north-west side, which in turn may have been caused by the rocky ground, making it difficult to dig a ditch. The height of the wall originally reached about 5.2 meters on the outside, but it varied in different parts of the town due to different ground levels and its inclination. On the inside, defenders moved along a wooden porch or platform, placed at the level of the offset (in the thicker north-western section it was placed higher than in the rest of the town). The wooden platform provided access to simple slit-shaped loopholes pierced in the parapet.

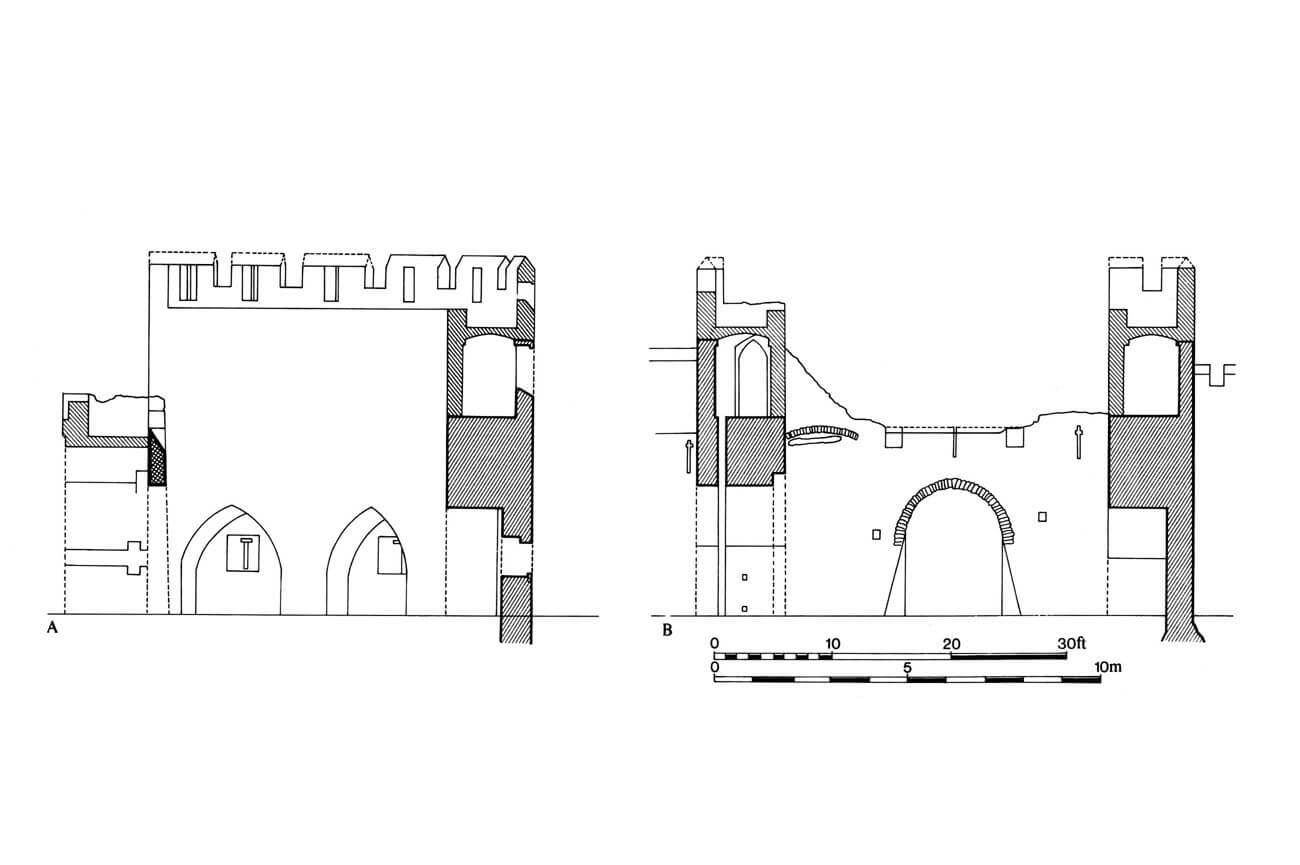

In the 15th century, the wall on the western section of the fortifications was raised by 1.5 meters (to about 7 meters high) and widened on the town side by 1.8 meters, thanks to which it gained a stone wall-walk based on arcades. The arcades were cheaper and quicker to build than solid thickening along its entire length, and they also allowed for the continued use of most of the lower arrowslits (original openings of the parapet). In the north-western part of the town, where the wall was originally thicker, it was only raised on the original offset and equipped with a new parapet. The wall acquired battlements everywhere, in the merlons of which loopholes were placed in the form of long vertical slits with short horizontal slits. The quadrangular openings in the lower part of the parapet would indicate that, at least in times of danger, the wall was also equipped with a hoarding.

The perimeter of the walls at the end of the Middle Ages was reinforced with several towers: quadrangular, cylindrical and horseshoe-shaped, most densely arranged on the long western section. Since it were mostly different in shape and size, it were not part of any single, comprehensive plan to strengthen the defences, but were built gradually, in places that were currently considered to be most vulnerable. Ultimately, the towers were distributed relatively evenly across the western section of the town. All were well forward in front of the adjacent curtain walls. Its role was to provide flanking fire and to prevent from climbing ladders or undermining the wall.

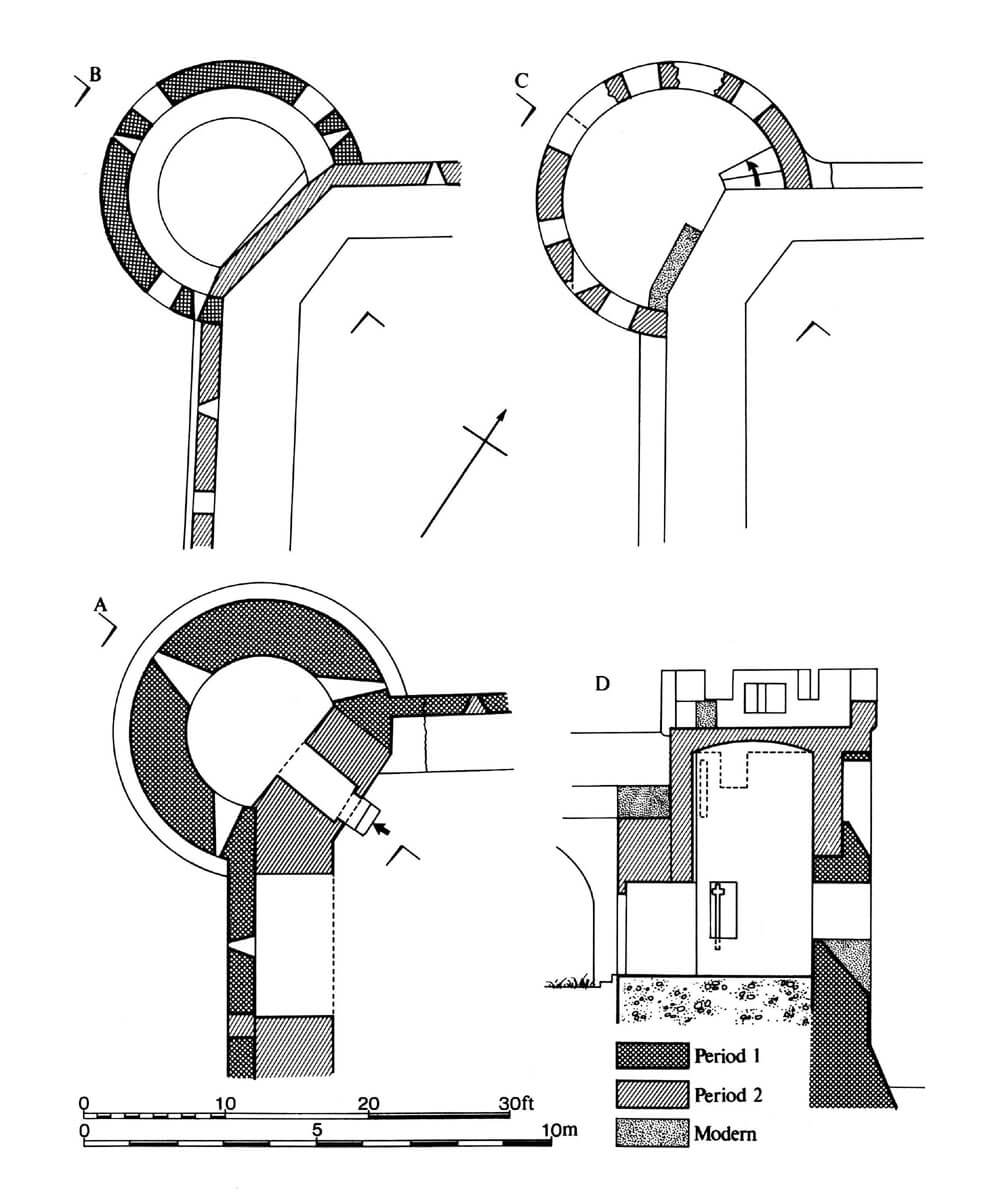

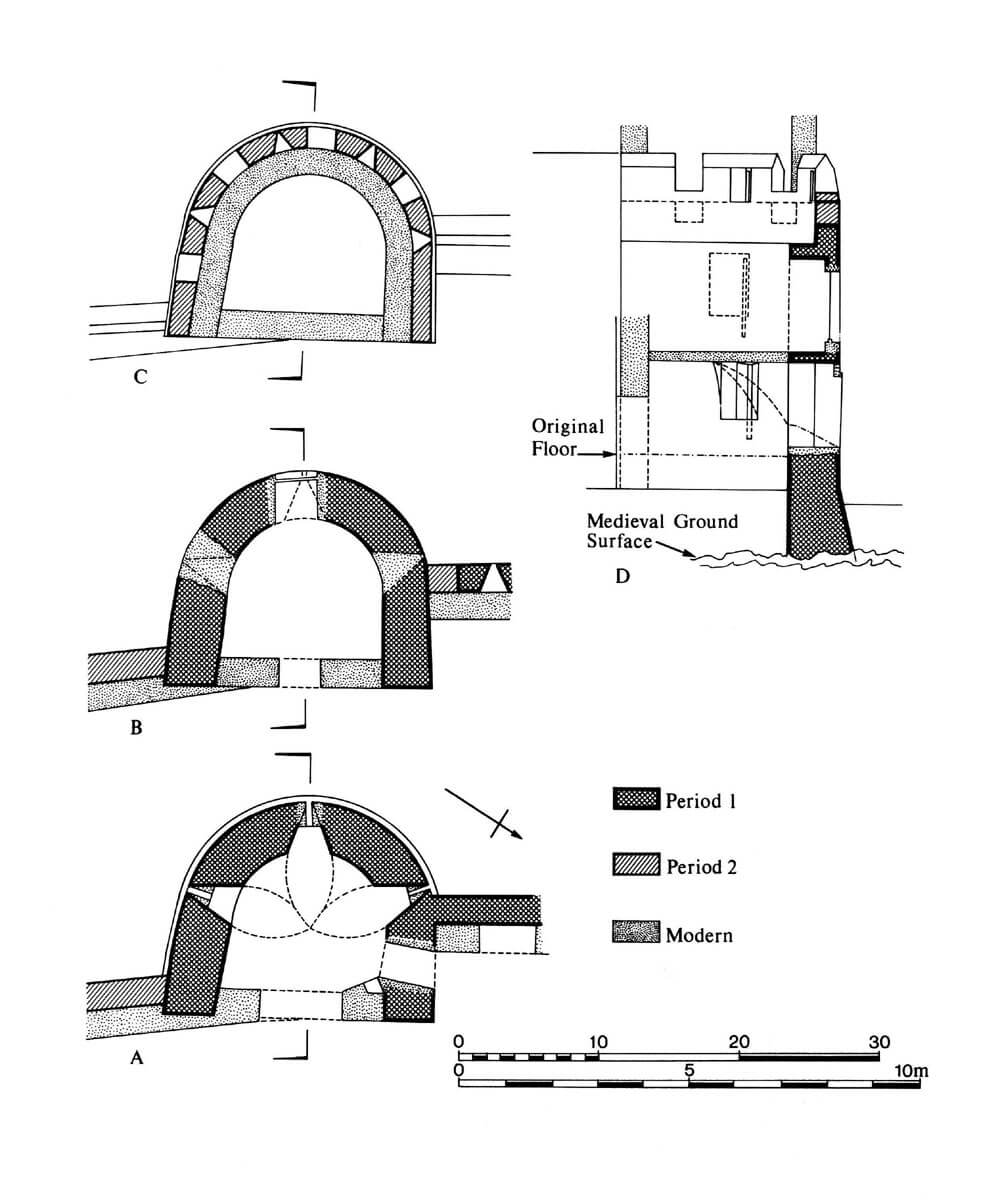

One of the oldest towers of the Tenby fortifications was the rounded corner north-west tower with an external diameter at the ground floor of about 6.4 meters. This is evidenced by very simple, splayed inwards loopholes in the form of very high slits. Three such loopholes were pierced on each of the two storeys, where two were directed towards the neighbouring curtains of the defensive wall and one directly into the foreground. In the mid-15th century, the tower was raised together with the wall and provided with a battlemented parapet mounted on a row of corbels protruding from the face. At that time, the second storey of the tower was also vaulted. Access to the tower was possible from the town side, through a straight rear wall, which could have been a secondary addition from the 15th century. Even after being raised, the height of the tower was not large, as it exceeded the defensive wall only by the height of the parapet.

Another early defensive work was the horseshoe tower in the southern part of the town (Belmont Tower), in the Middle Ages opened on the inside, two-storey, with an unroofed combat platform at the very top. It was equipped with similarly simple slit-shaped loopholes, splayed towards the inside, but without niches allowing for greater freedom of movement for shooters. Three such loopholes were placed on each storey, practically on the same axes, additionally limiting the field of fire. Additional arrowlits were placed after the 15th-century raise of the tower in the merlons of the parapet, which was in line with the older part, not mounted on corbels. The tower was situated in a place that was part of the seaside cliff. Initially, it was the end of the fortifications on the southern section, or the final part was made of wood. It was not until the 15th century that the wall was extended from the east by a dozen or so meters and ended with a small quadrangular corner tower. The late medieval curtain was connected to the rear part of the horseshoe tower, not to the central part, like the older western curtain, which is why the side arrowslits of the tower in the east were not directed at the new section of the wall. This could have been due to the irregularity of the cliff rock or other conditions of the natural shape of the terrain. The quadrangular 15th-century tower on the edge of the fortifications had no internal rooms and served primarily as an combat platform, accessible by wooden stairs from the wall-walk.

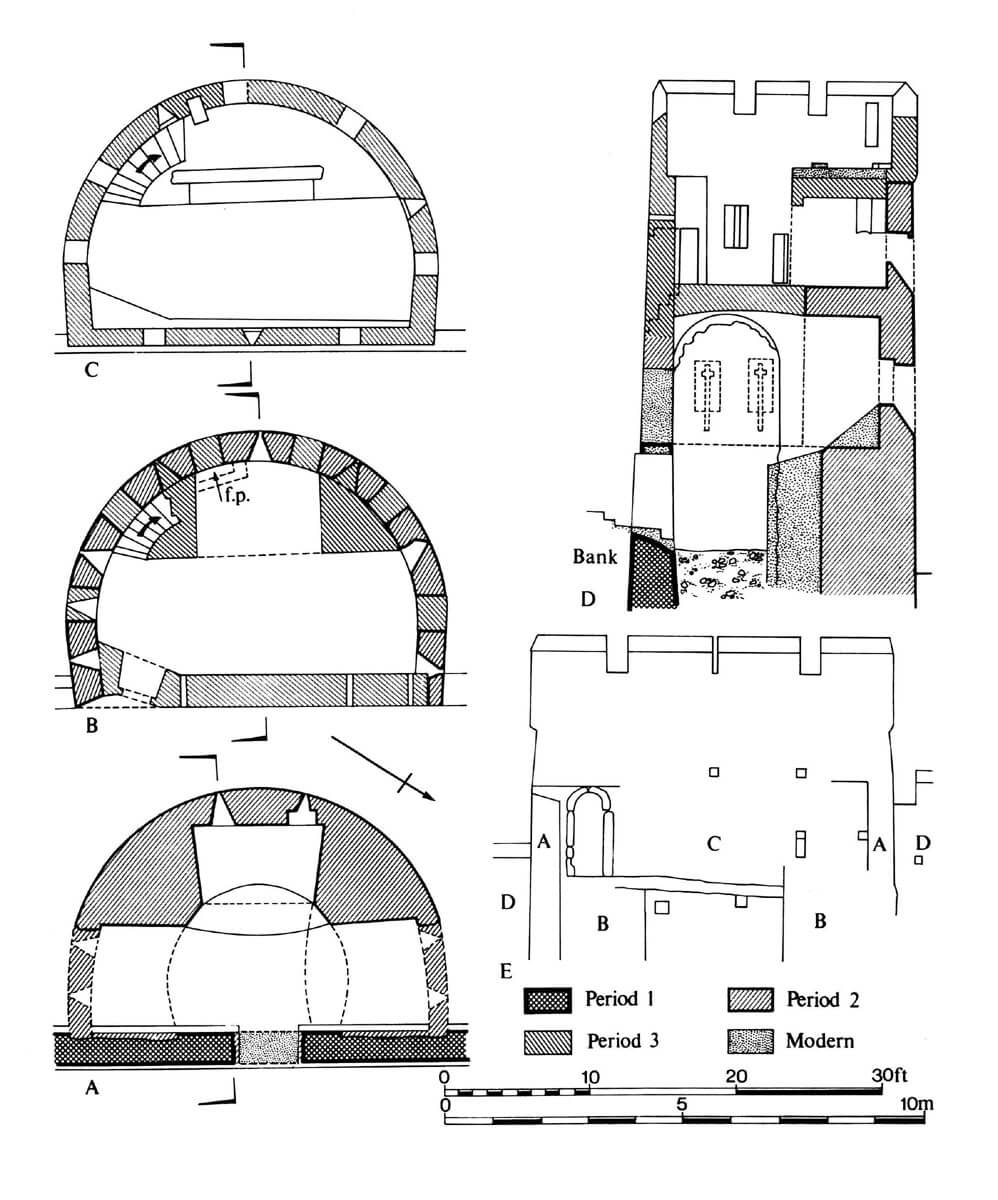

The central part of the western section of the town wall was defended from the early 14th century by two semicircular towers of similar shape and size. Both were added to the curtain wall from the outside, and both were also topped with an unroofed combat platform. The splayed inwards arrowslits of the towers already had semicircular and segmental niches created inside in the thickness of the wall, with the southern tower having two arrowslits in the side niches on each of the two storeys, and one in the central niche, facing directly into the foreground. The northern tower in the central niche of the second storey (the first one was the unlit ground floor) was equipped with two arrowslits, similarly to the side niches. When it was raised in the 15th century, in order to adapt to the raised curtain, it was transformed into an stand-alone unit that could be defended independently of the neighbouring wall. The upper level of the tower was then adapted for residential purposes by inserting a fireplace, placed in a niche constituting a platform for the new parapet.

In the later years of the 15th century, a tower was built on a quadrangular plan between the two southern horseshoe towers. It was the only one to be added to the already raised curtain. The vaulted space of the ground floor and the high chamber on the first floor were equipped with loopholes splayed towards the interior, all in the form of a key loop, with a circular opening in the lower part of the longitudinal slit. The first floor had the convenience of a corner fireplace, while at the level of the unroofed upper combat platform there was a latrine, although these two levels were probably not directly connected. There may have been an opening for a ladder in the ceiling, but the entire tower was part of a larger half-timbered house on the inside of the wall, which probably had a staircase. The tower, together with the house, could have provided quarters for a small garrison or for those who periodically performed duty on the walls (in 1586, records mentioned a “guard house”, possibly identical with the quadrangular tower and the adjacent building).

Originally, there were two main gates to the town: the Great Gate, also known as Carmarthen Gate, on the north-west side, and the western gate. The most important was the Great Gate, facing the route to Carmarthen and on to Cardiff. The western gate, although it acquired an impressive form, led only towards the fields, the coastal route to Pembroke and Saltern, which was an alternative place to unload ships if the port could not be reached. In addition, on the less important coastal section from the port side to the north, there could have been smaller gates leading to the waterfront. It probably had the form of ordinary portals pierced in the wall, although were guarded by a late medieval quadrangular Harbour Tower, situated at the narrow isthmus between the town and the castle, near the causeway or breakwater that protected the harbour. There were probably also two small round towers in the line of the wall on the eastern side of the isthmus.

The Great Gate probably consisted of two towers flanking the passage between them. It may have been similar to the northern gate of Pembroke town, which would have made it fit well into the limited space in the corner of the town. If it was similar to the drawing on the 15th-century Tenby seal, then the towers on the sides of the passage were not massive, but topped with battlements and pierced with loopholes. A battlemented parapet may also have been located above the central part of the gate, above the passage closed by a portcullis, flanked by two more loopholes. According to the drawing on the seal, all the loopholes were in the form of two cross-cutting slits with round holes at the ends. Some records would indicate that there was also a foregate in front of the gate.

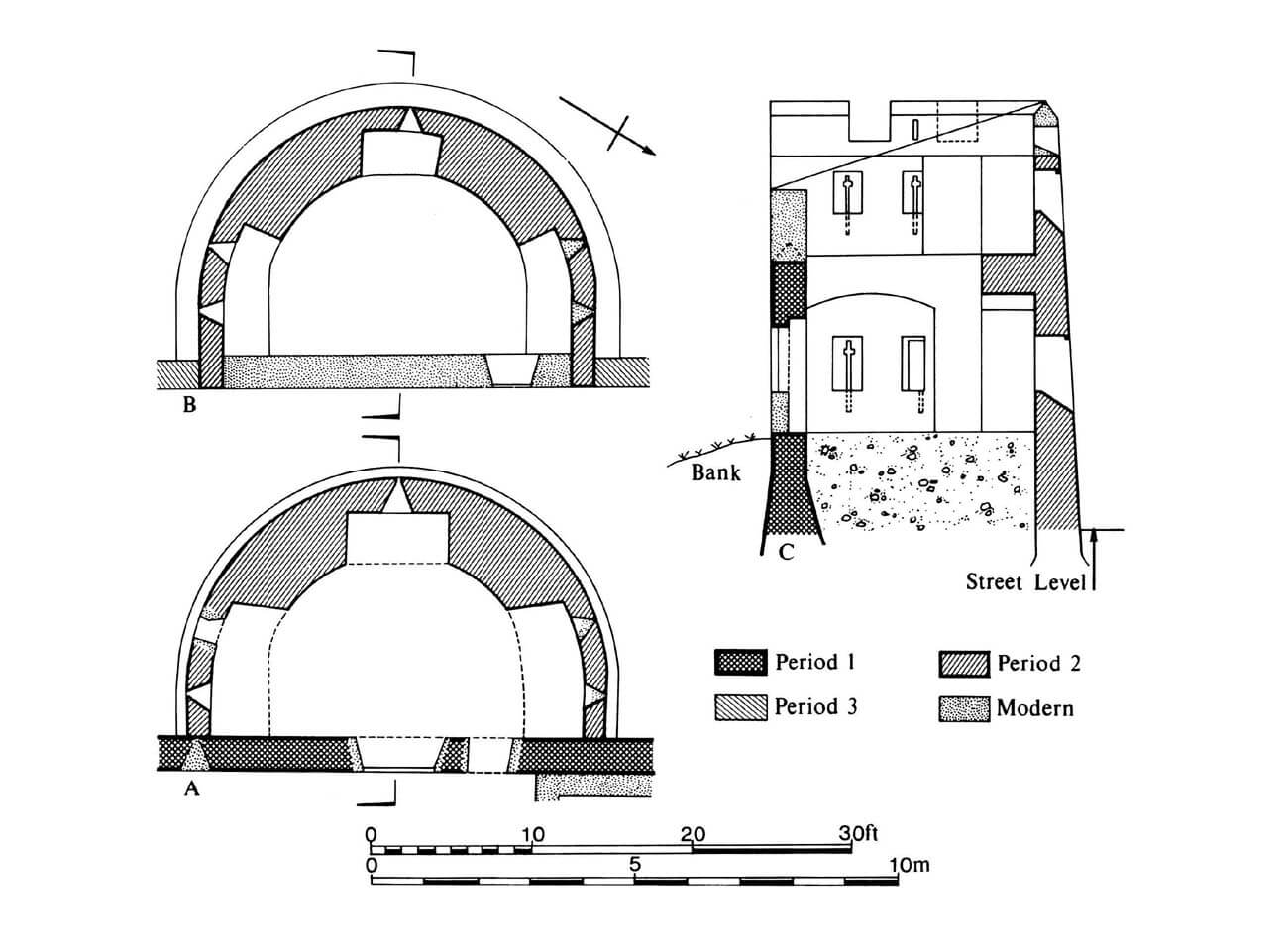

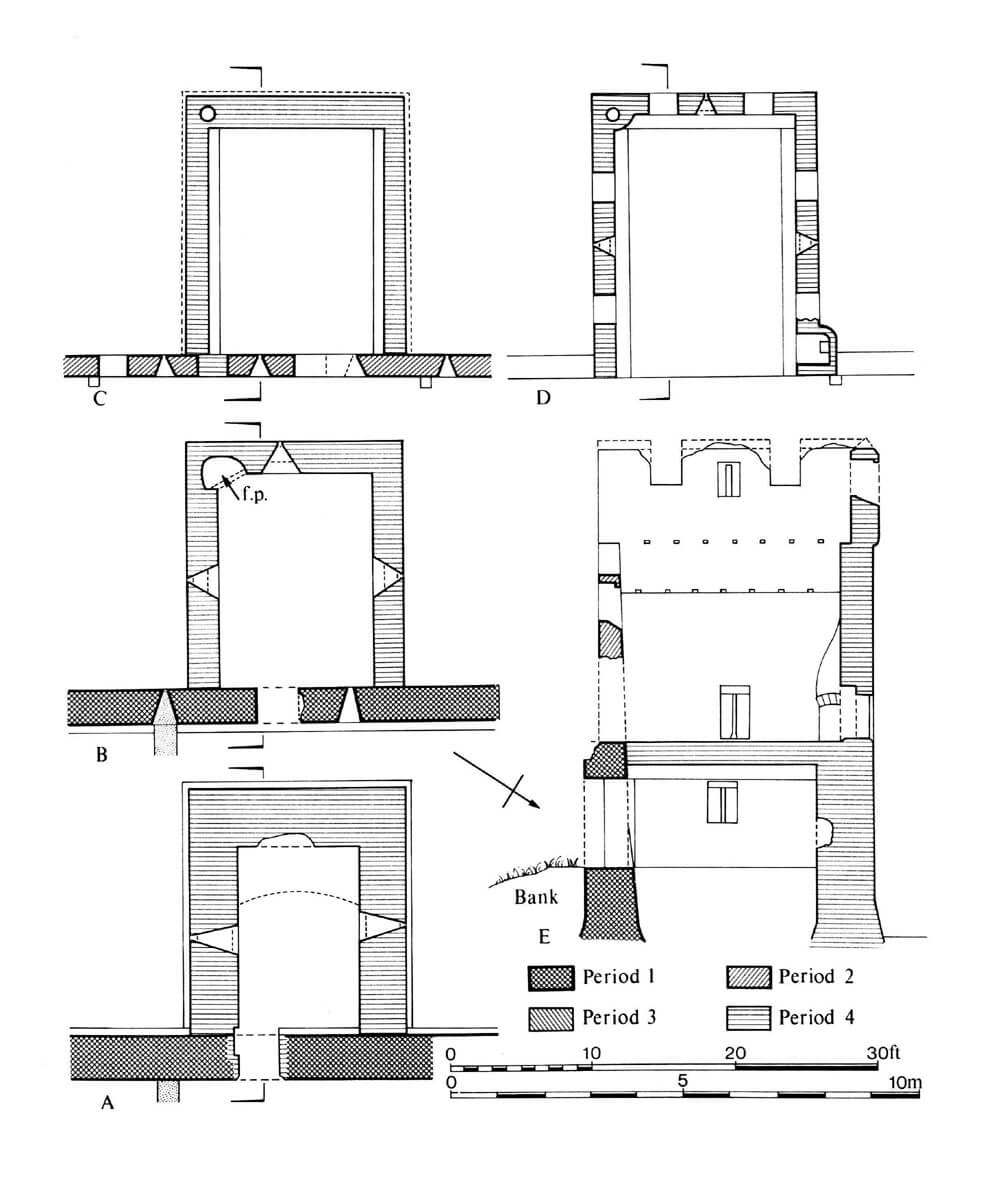

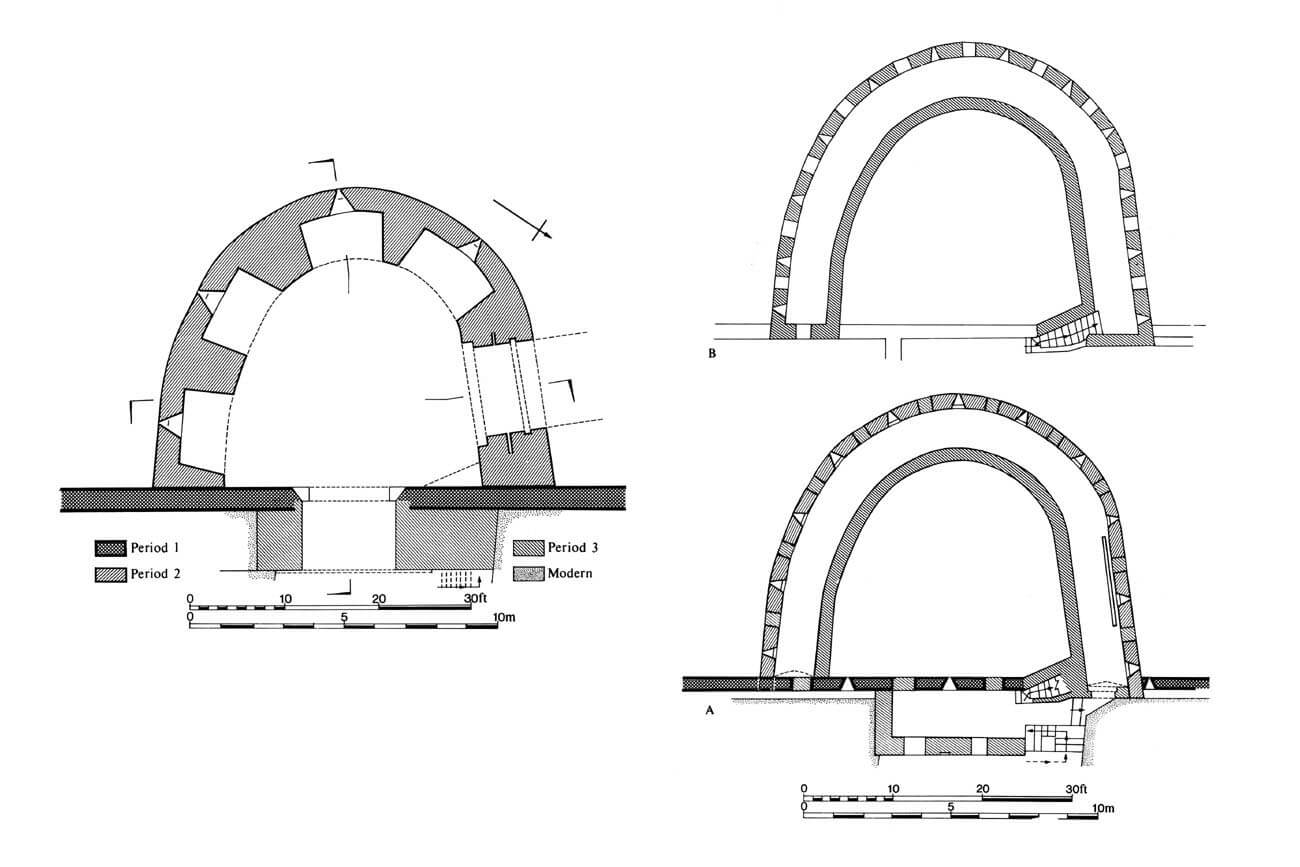

The western gate was initially an ordinary portal pierced along the length of the curtain. Around 1320, it was preceded by a horseshoe-shaped barbican, which was fully adjoined to the curtain wall from the outside. The entrance to it was pierced in the northern wall, forcing attackers to stand sideways to the curtain wall. The smaller foregate in front of the castle had a similar form, and both could have been modelled on the horseshoe-shaped gatehouse at Pembroke Castle or on the foregate of Goodrich Castle, another property of the earls of Pembroke. The entrance to the barbican in Tenby was closed by a portcullis, external doors blocked by a bar pushed into holes in the wall, and internal door. In addition, the massive barbican wall at ground level had four recesses with arrowslits facing the moat, which was widened in the 15th century to 9.1 metres. The second storey was a vaulted defensive gallery with a row of regularly spaced 11 gun loopholes. Alternating with them were loopholes set in merlons on the upper, unroof gallery. The first floor originally was an unroofed wall-walk, but the barbican was raised and the older battlement was bricked up in the 15th century. The rear wall of the barbican was not raised at that time, but reinforced with a massive additional wall, which created an internal gate passage, located on the town side, topped with an open platform with battlement.

Current state

Tenby’s fortifications are among the best preserved medieval town walls in Great Britain. A very long section of the defensive wall on the south-west part of the perimeter (South Parade Street) has survived, along with six towers and a gate barbican. The latter is the most distinctive element of the old fortifications today, although the passages in it, all but one (the northern one), were created in the 20th century to improve communication. Similar large breaches were created in one of the neighbouring horseshoe towers. On the external elevations of the barbican, as in many other places on the defensive wall, older levels of fortification are visible, from before the walls were raised in the 15th century. A long section of the defensive wall has survived in the northern part of the town, but unfortunately there are no visible traces of the Great Gate. The section of wall on the harbour side has undergone significant transformations over the centuries.

bibliography:

Gwyn T.W., The walls of Tenby, „Archaeologia Cambrensis”, 142/1993.

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Salter M., Medieval walled towns, Malvern 2013.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, VII County of Pembroke, London 1925.