History

In 1106, the English king Henry I gave the Lordship of Gower to Henry de Beaumont, Earl of Warwick, who soon built a wood and earth stronghold in Swansea (Seinhenydd, Abertawe), probably in the form of a motte and bailey. Simultaneously with its construction, the Normans erected many other fortifications on the peninsula, including at Loughor, Oystermouth, Penrice, Penmaen, and Pennard. As early as 1116, Swansea was attacked, which was also the first written record of the castle. The Welshmen managed to destroy its external fortifications, but the tower (probably the keep) managed to defend itself. After the rebuilding, the castle was handed over to Roger de Beaumont, who replaced Earl Henry in 1119.

Probably in 1136 Swansea was briefly captured by the Welshmen. The Gower Peninsula was recaptured by Roger’s younger brother, Henry de Neubourg, two years later, who re-established Swansea as the seat of the lordship. In 1166, Henry was replaced by Earl William. In this time the castle was not mentioned in documents, but the first charter was issued for the settlement outside the castle. In 1184, Swansea, along with the entire peninsula, returned under the direct authority of the king, and the ruler appointed William de Londres, Lord of Oystermouth as the keeper of the castle. After a brief period of peace during the reign of Henry II, who made an agreement with Lord Rhys, the Welsh prince of Deheubarth, fighting resumed when Richard I ascended the throne. Swansea was attacked in 1192, but thanks to supplies and a strong garrison strengthened two years earlier, resisted the attackers and was not captured, despite the siege lasting 10 weeks.

In 1203, King John handed over Gower to William de Braose, though he quickly confiscated his estates when he began to suspect him of disloyalty. In 1208, Falkes de Breaute was appointed the castle custodian, William fled abroad, and his wife and eldest son were captured and starved to death. In Wales, survivors of the de Braose family came into open conflict with the Crown in collaboration with the Welsh prince of Gwynedd, Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. In 1212, Rhys Gryg, son of Lord Rhys, attacked Swansea Castle without success on behalf of William and Llywelyn, but the death of King John in 1216 and the reconciliation policy of his heir, Henry III, led the Crown to reconcile with the de Braose family. The change of allies resulted in a retaliatory attack on Swansea, initiated by Llywelyn ap Iorwerth. In 1217, Gower invaded Rhys Gryg, who captured Swansea and banished the Anglo-Normans. The de Braose family regained control of Swansea three years later, as part of an agreement between Llywelyn ap Iorwerth and Henry III, though Llywelyn had to forcibly take Gower from Rhys, who did not recognize the agreement with the king. During the peace period that followed, Swansea Castle began to be rebuild into stone one, probably between 1221 and 1284.

In 1257, Rhys Fychan, assisted by his feudal superior, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, invaded and burned the town of Swansea. Although the castle could have suffered damages at that time, the English power of the de Braose family was quickly restored. In 1284, King Edward I stayed at Oystermouth Castle and not at Swansea, which may have been due to construction works going on there. They were certainly completed in 1287, because then the Welsh rebels of Rhys ap Maredudd did not manage to take the castle, although they burned the Swansea town and Oystermouth Castle. After the Welsh wars of independence of 1276-1277 and 1282-1283, the political situation changed radically. Edward I defeated the last independent Prince of Wales and conquered his lands. Due to the reduced threat, Swansea Castle was at the end of the 13th century and at the beginning of the 14th century rebuilt into a comfortable residence, since 1291 the seat of William de Braose III.

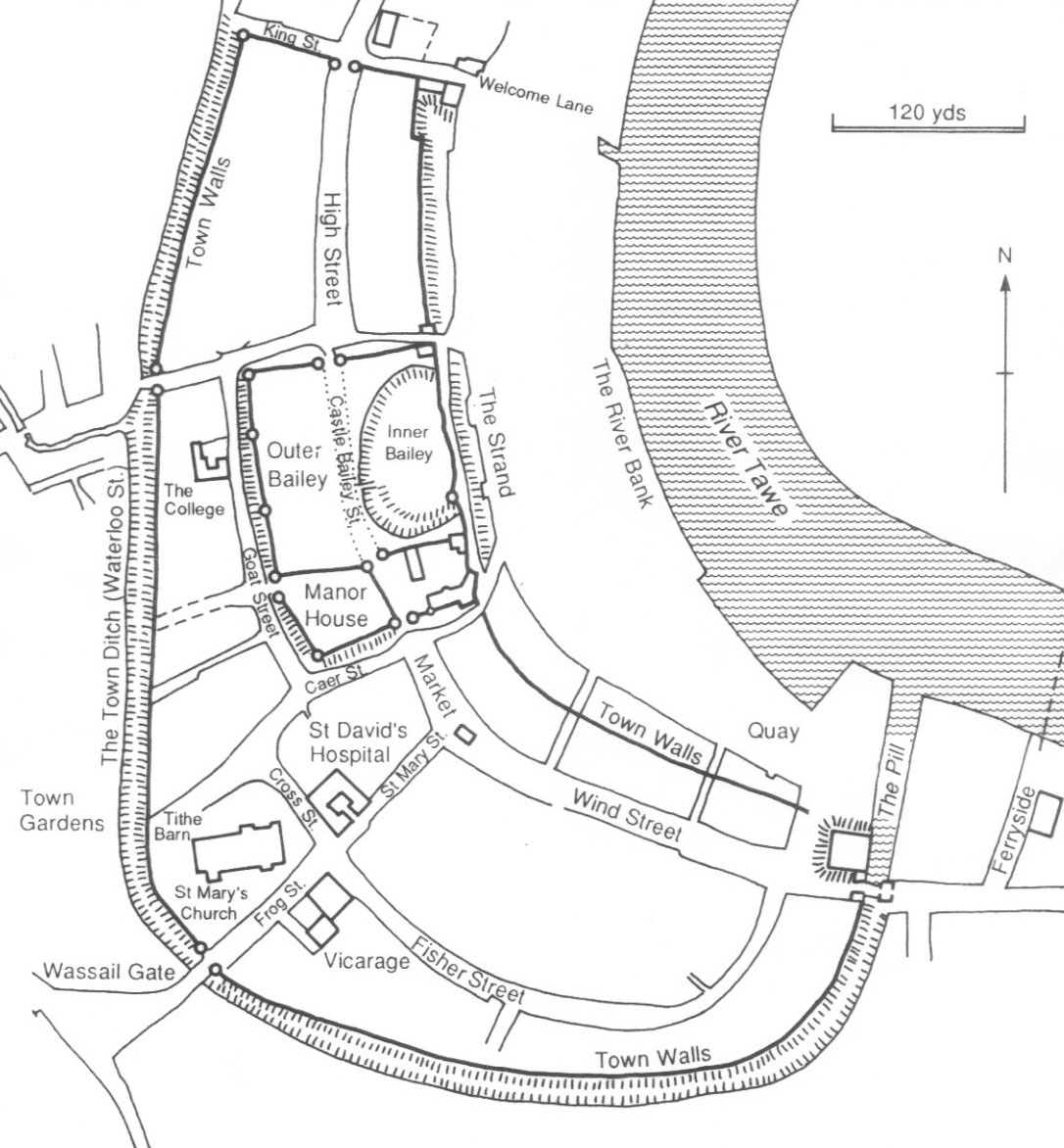

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the town grew significantly and was surrounded by stone walls, which made the castle quite unusually inside their perimeter. During this period, formal rule over the Gower Peninsula was exercised by Alina de Braose, from 1298 the wife of John de Mowbray, the second baron of Mowbray, who in 1321 joined the rebellion of Thomas, Earl of Lancaster against Despenser, the hated favorite of Edward II. Mowbray fought the King’s forces at Boroughbridge, was captured after the battle and executed that same year, and his estates was forfeited to the Crown. Despenser secured the Gower Peninsula, which he formally received from the king in 1322. In Swansea, he was to punish 14 townspeople with confiscation of property and imprisonment for supporting Mowbray. Alina de Braose, along with her second husband Richard de Peshall, regained the castle and the rest of the estates after the fall of Despenser in 1326 and the accession to the throne of King Edward III in 1327, but she still had to contend with an investigation into the royal jewels deposited at Swansea Castle and stolen from there.

Swansea was returned to the Mowbray family, although they rarely visited the castle. William de Braose probably neglected it, which made Alina prefer to reside in Oystermouth. In 1331, the Gower lordship passed to John de Mowbray, the third baron of Mowbray. Documents did not record any major construction investments by him, and he rarely visited the Gower Peninsula. In 1335 he was instructed by the king to strengthen the defense of the coast and all owned castles due to the Scottish invasion. In 1354 he was forced to hand over Swansea Castle and the lands of Gower to Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick. The Beauchamps also did not live in Swansea, but entrusted the castle to their officials who maintained the administration of the subordinate lands. Despite the spreading epidemic of Black Death, urban buildings were developing, which, under Thomas Beauchamp II, in the second half of the fourteenth century, began to enter the area of the outer bailey.

In 1400, the great Welsh uprising led by Owain Glyndŵr broke out. Rebel forces occupied most of the Gower Peninsula between 1403 and 1405, but Swansea Castle most likely was not attacked. Its custodian at the time, Sir Hugh Waterton, ordered the necessary repairs to be carried out and the fortifications to be strengthened (the moat was cleaned, masons patched up the defects in the walls, carpenters were hired to restore timber elements). At that time, the garrison was to consist of three men-at-arms and 18 archers. The rebellion was finally suppressed in 1410. In the same year, an inventory was also carried out, stating, probably with an exaggeration, that the castle is not suitable for repairs and that the estates under it are devastated.

In the following years of the 15th century, the owners of the Mowbray family, the Dukes of Norfolk, were less and less likely to stay at the castle, which was systematically losing its importance and was used only as a prison, although in 1449 and again in 1478-1479 the new residential and defensive buildings were recorded under the misleading name of the New Castle, probably a kind of a manor house in the town, attached to the moat of the old castle. It could have been funded by John Mowbray, third Duke of Norfolk, after coming of age in 1436. Another manor house called New Place, located in the outer bailey, was built at the end of the 15th century by the then keeper of the castle, Sir Mathew Cradock. In the older part of the building, he kept chambers in case of rare visits of the lord, he was also responsible for the castle garrison, which in 1526 was to protect Oystermouth and Swansea with a force of 24 men-at-arms.

Cradock’s successor was Sir George Herbert, who in 1534 repaired roofs and prison cells. As early as 1583, however, the “castel of Swanzey” was described as dilapidated and destroyed. When the English Civil War broke out in 1642, the castle was in such a bad condition that neither side used it in combat. In the 1670s, the square tower of the castle was used as a bottle factory, and in 1700, the town hall was built in the castle courtyard. Then the area of the castle was used by the army and prison services. In the 1840s, the course of the Tawe River was changed, and it stopped flowing near the ruins of the castle.

Architecture

The original wood and earth castle was erected on a rectangular plan with rounded western corners. It was protected on the eastern side by the Tate River, near its confluence with Swansea Bay and the Bristol Channel. Also it was situated on the highest point of the riverside slopes, about 1.5 km south of the crossing connected with the old Roman road. Inside the fortified perimeter, occupying an area of about 38 x 60 meters, there was an earth mound (motte) at least 6.4 meters high above the level of the ditch (about 4 meters above the level of the courtyard), on which a timber tower of the keep function was probably erected. The ditch had a flat bottom, formed at a depth of 2 to 3.5 meters below the medieval ground level. Its width was just over 10 meters, with a bottom about 2.7 meters wide.

In the first quarter of the 13th century, the castle began to be rebuilt using stone. Wall about 1.8 meters thick, reinforced with a single, four-sided tower on the west side was erected. The tower protruded 6.4 meters in front of the adjacent curtains, and its front elevation, 9.1 meters wide, was created on the slope of the mound. The inner part of the tower, located in the courtyard, was only about 1 meter long. The thickness of the tower walls was slightly greater than that of the curtains, as it was about 1.9 meters. The whole complex could have inspired a slightly later castle in Loughor, with a very similar shape in plan.

During the 13th-century rebuilding, the castle was enlarged by a new, outer ring of defensive walls on a rectangular plan with impressive dimensions of about 100 x 150 meters, with longer curtains on the north-south line. In the course of further works from around the mid-13th century, the circuit was reinforced with four corner towers, and the gates were placed in the northern and southern curtains (at least one of them consisted of two horseshoe towers flanking the middle passage). The older complex then began to constitute the eastern, riverside part of the castle, while in the middle of the outer bailey was a road running from the north to the south, leading from the northern town gate towards the market square and the parish church. The castle was found quite atypically inside the expanding town, surrounded by a stone wall until the end of the 13th century from the north and west, from the east protected by the river, and in the south and south-east by its wide mouth and swamps.

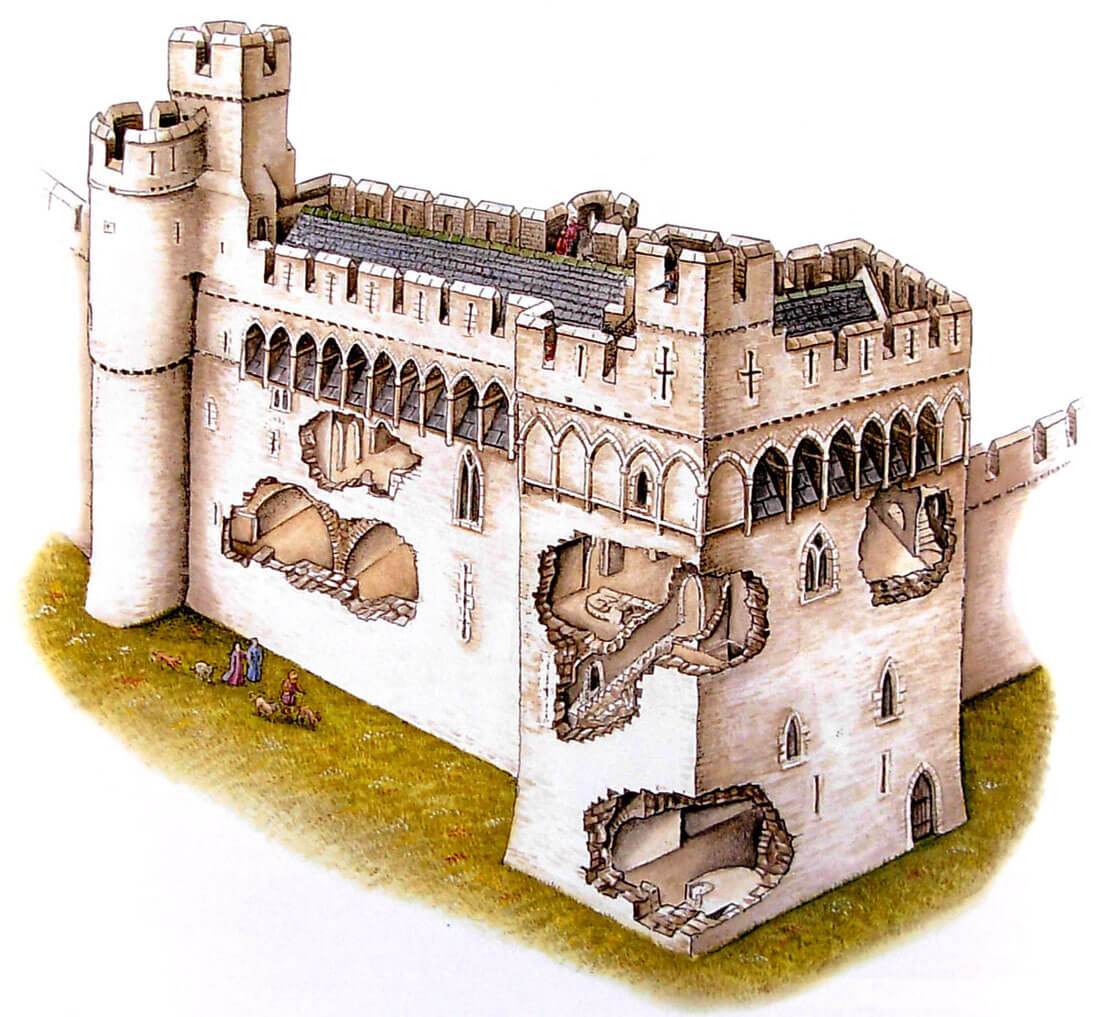

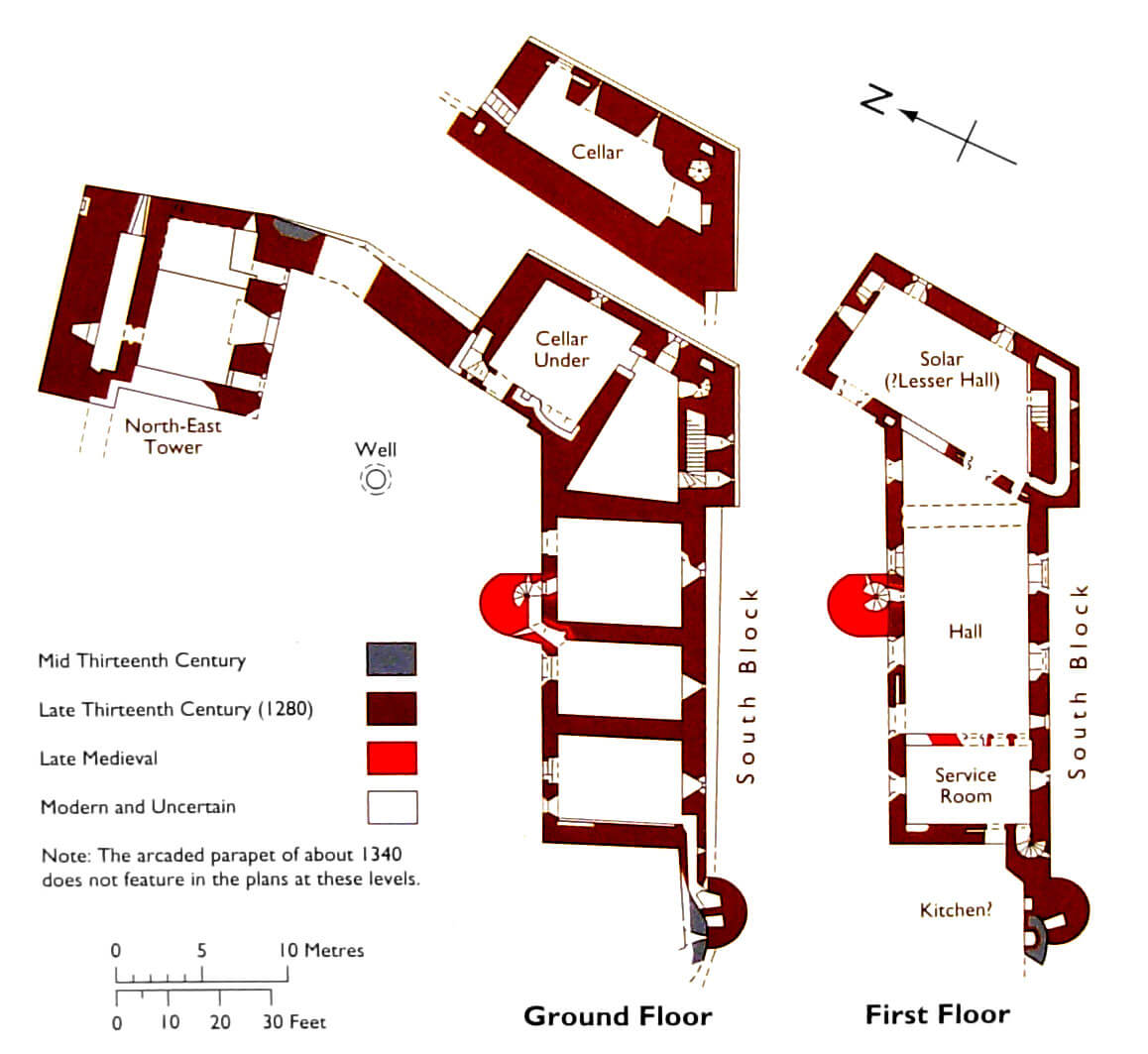

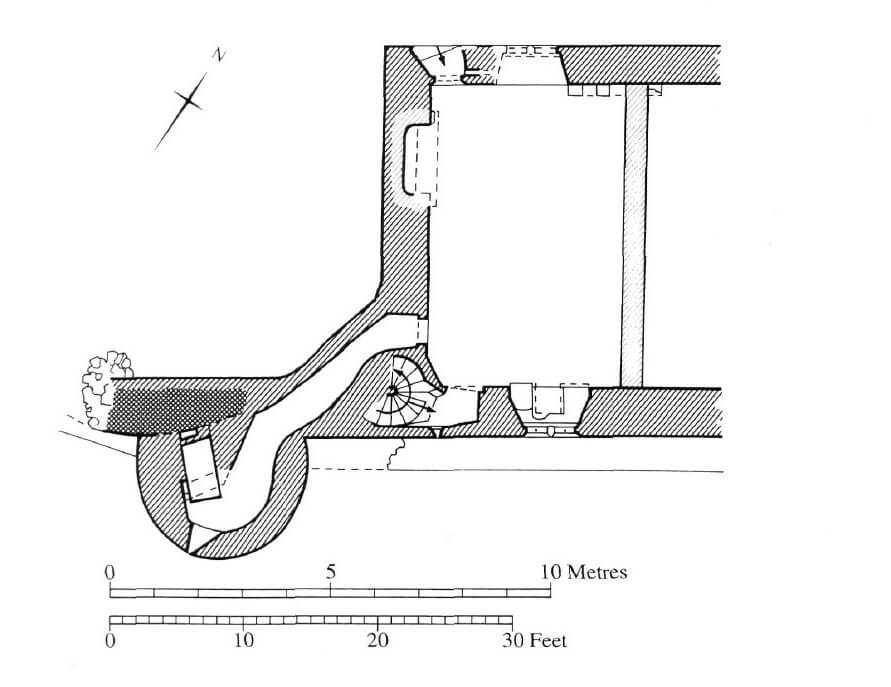

In the south-east corner of the outer perimeter (outer bailey), the so-called New Castle was erected at the end of the 13th century. It consisted of a two-story building of a great hall, a semi-cylindrical latrine tower located in its western part and a quadrilateral, irregular corner building with of a tower character (Solar Tower) located on the eastern side. Further on the north-eastern side, at the end of the short, slightly bent eastern curtain of the wall, another four-sided, corner tower was placed. No traces of less important economic buildings were found, which, being a wooden or half-timbered structure, could be attached to the perimeter walls. In the center of the courtyard there was a well with a depth of 12 meters.

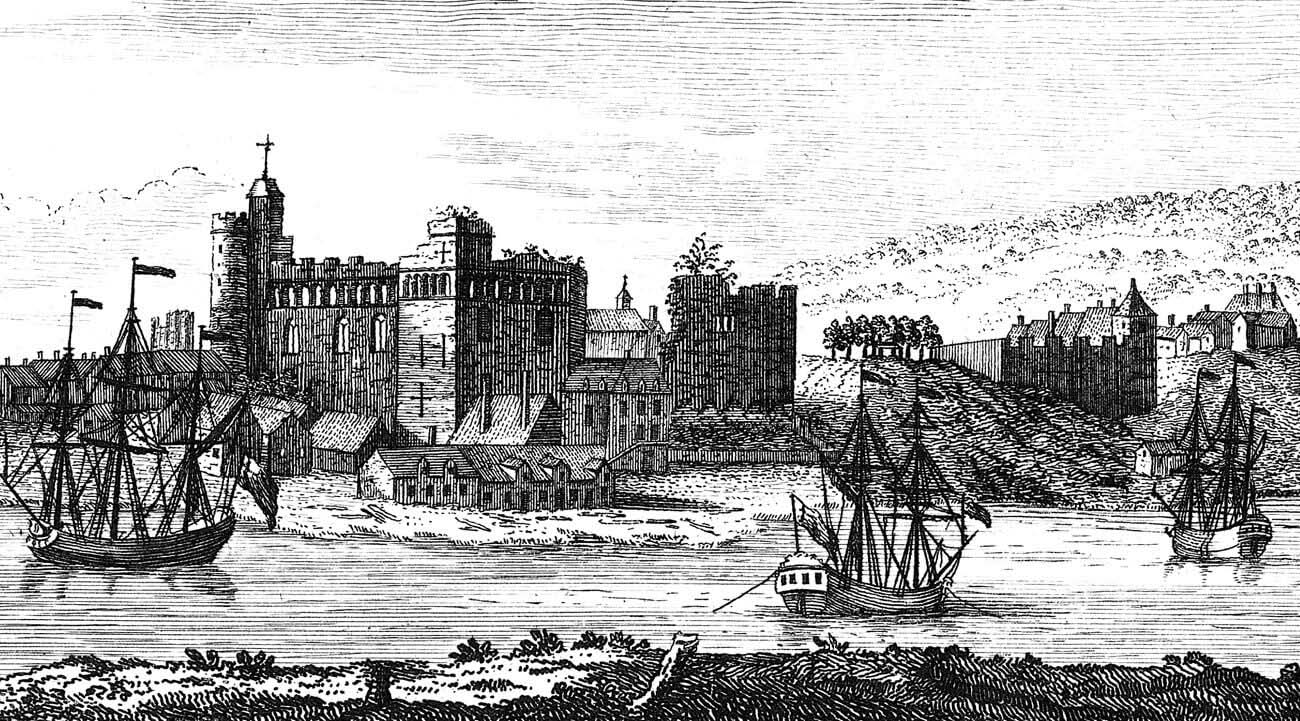

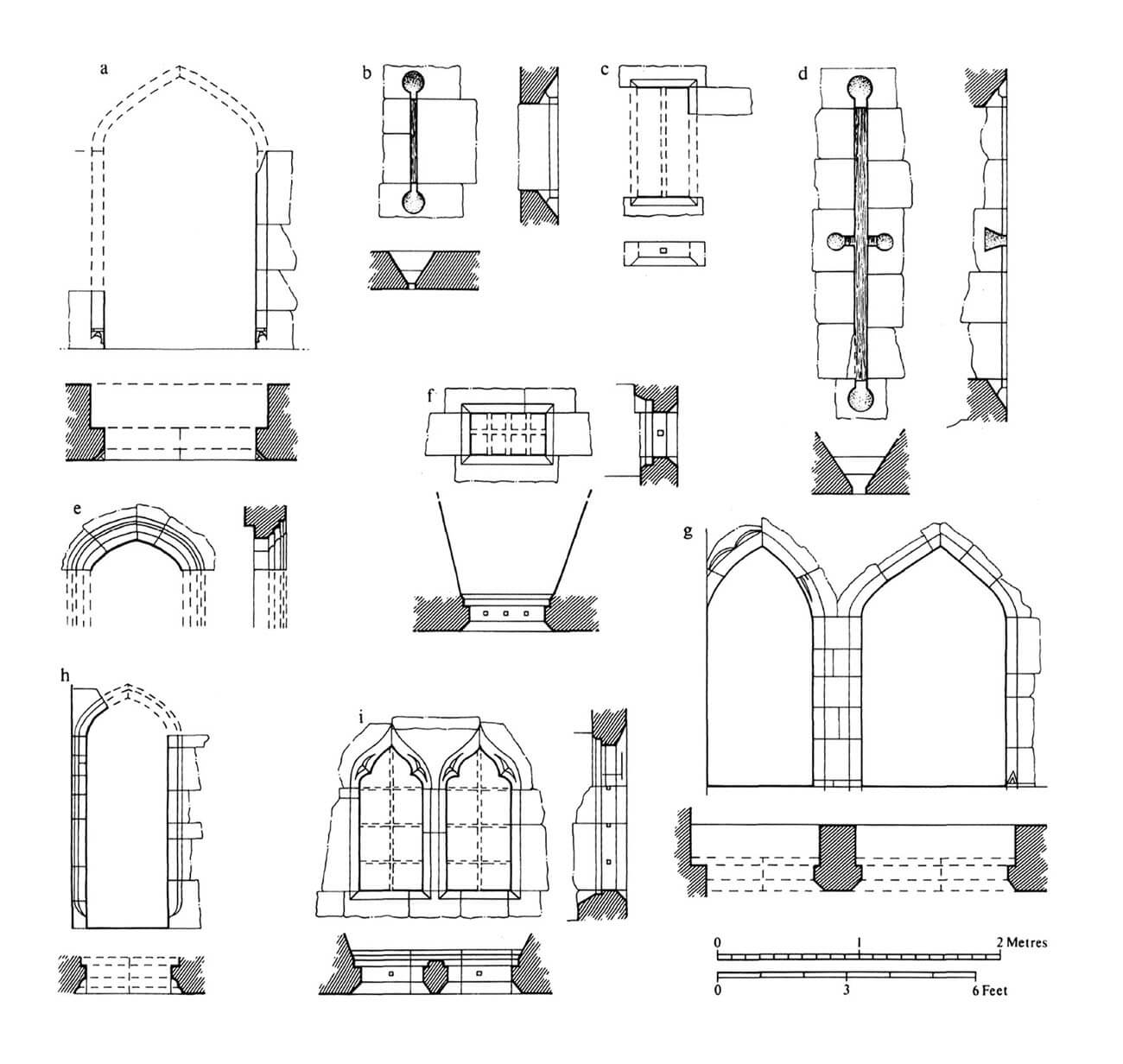

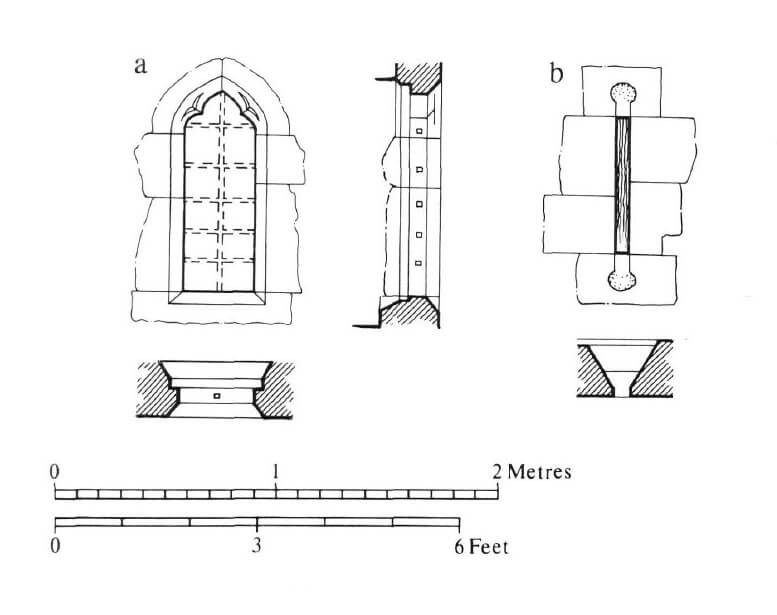

The hallmark of the southern wing and the south-eastern tower was a row of arcades made of white Sutton stone built around 1330, above which a parapet with merlons pierced by arrowslits was placed on the row of corbels. Under the arcades, there were ogival windows of the great hall, and lower arrowslits illuminating the lowest floor. The arcades, apart from their decorative role, were used to drain rainwater from the longitudinal roof of the wing. This goal was fulfilled by sloping roofs under each arch, protruding outwards as a drip between the arcade’s shafts. In the west, they ended about 3 meters in front of the corner semicircular tower, in the facade of which five narrow openings illuminating the staircase were pierced. The highest of these openings was placed at the level of the battlement of the wing, in the part of the building changing into a four-sided observation turret, located on the edge of the corner tower and the wing. On the south-eastern tower, five southern and two eastern arcades were blind, but the central arcades of the eastern façade were identical. From the north side (facing the courtyard), only the south-east tower was decorated with arcades, because the wing had too thin walls to support the arcades and the parapet on that side. Similar arcades as at Swansea were still used in the episcopal palaces of St Davids and Lamphey, but there is no evidence that Bishop Henry de Gower was responsible for the work outside his estates. The southern wing, after the reconstruction from the fourteenth century, served as a comfortable and representative building, not devoid of defensive values, due to the squeezing of the New Castle between the ditch and the fortifications of the older complex from the 13th century.

The main entrance to the hall was on the first floor and led through the outer stairs from the courtyard side. Next to it, there was a late-medieval, semi-cylindrical turret with a staircase. It connected the hall on the first floor (12 x 7.5 meters) with two vaulted utility rooms in the ground floor. The third extreme room in the west was connected by a long and narrow passage in the thickness of the wall with the latrine in the western semicircular tower, and all three ground floor rooms were accessible through portals from the courtyard side. Until the late medieval communication turret was built, the lower rooms did not have a direct connection with each other. The hall on the first floor from the west was adjacent to a smaller service room, in which the dishes were probably prepared before they were brought into the great hall. As many as three portals served for communication between these rooms. Further to the west, a kitchen could be expected, but no remains of it have survived. In the hall, the eastern part, due to the daise and the main table of the castle’s lord, had to be fenced off with a partition wall, creating a triangular room at the corner tower. The lighting of the hall was provided by two northern and two southern large, pointed windows with side seats in recesses. A smaller four-sided window illuminated the entrance vestibule from the south, probably separated from the rest of the hall by a screen in the Middle Ages. The fireplace had to be on the opposite side, in the eastern wall. The hall was covered with an open roof truss, and the adjacent rooms with flat ceilings, above which additional low chambers were created. Interestingly, both the western entrance to the service room, as well as the main entrance to the hall and the eastern portal to the tower were locked with draw-bars, set in openings in the wall. The main representative room and adjacent rooms could therefore be a shelter, separated from the rest of the castle.

The south-eastern tower (Solar Tower), due to its foundation on the ground sloping towards the river, additionally received a basement, located below the two upper floors. Probably due to the proximity of the river, it was used to store goods brought in by a postern, locked with a draw-bar. The basement was covered with a pointed barrel vault, pierced in two places with openings communicating with the rooms on the ground floor. It was illuminated by two splayed, narrow openings, although no light came directly into the southern recess with a separate vault. Next to it, there was probably a spiral staircase connecting to the ground floor. The ground floor of the tower was divided into two chambers: a quadrilateral in the northern part, equipped with a fireplace and a latrine, and an irregular one in the southern part, adapted in shape to the link with the southern wing. Southern room was connected by a simple staircase in the thickness of the wall with the upper floor. Both chambers were covered with vaults, while the southern one was erected in stages, probably due to problems resulting from the unusual shape. Both chambers were also lit with single windows. The northern one probably served as a brewery or similar utility room, while the southern one was a warehouse. On the first floor there was one large private room (lesser hall), accessible by stairs directly from the courtyard and through a triangular room behind the hall. The chamber was heated by a fireplace, equipped with large windows with side, stone benches in niches and a latrine discreetly hidden in the wall, located at the end of a long passage embedded in the wall thickness behind the stairs. In addition, there was a timber gallery that could be used by musicians or poets during their performances in front of the owners of the castle. The gallery was mounted on two large stone corbels. It was open to the roof truss, illuminated by a trefoil window, it was accessible by the stairs in the north-east corner. The south-eastern corner of the tower, probably due to the desire to control the river and the town, was raised to the form of a four-sided observation turret, topped, like the tower itself, with a battlement.

The corner north-east tower had the form of a quadrilateral with dimensions of 12.5 x 11 meters, with a slight projection in the corner with the stairs inside. Its ground floor was divided into three vaulted rooms of different sizes, without connection to the first floor. Two were located on the side of the courtyard from which the entrance portals led to them, and the third, narrow and longitudinal one, was placed in the wall of the tower on the north side. The latter probably housed only a cesspit from the upper latrines, although it was lit by two small openings: one pierced high from the north and one, extremely deep, in the eastern wall. It seems that they were created earlier, before the ground floor was divided into chambers, when they illuminated one, not yet vaulted space. The first floor of the tower with chambers heated by fireplaces and a latrine in the northern corner was significantly transformed in the early modern period, when it was adapted to a prison. Presumably, in the Middle Ages it served the garrison of the castle, which was related to the simple, completely utilitarian appearance of the tower. The first floor was connected to the wall-walk in the crown of a slightly bent, 11-meter long eastern curtain. The wall-walk there was between 2.5 and 3.5 meters above the level of the courtyard. On the north side, the curtain, which was less than 2 meters thick and about 20 meters long, already had a wall-walk at a height of less than 7.9 meters. It was crowned with a parapet mounted on corbels, below which a vaulted passage 1.2 meters wide and 1.9 meters high was placed in the thickness of the wall. This passage was connected with the north-eastern tower at the level of the first floor.

Current state

Only the ruin of the so-called New Castle from the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries has survived to the present day. You can see the walls of the southern wing, a communication turret in the former courtyard, a quadrilateral tower (Solar Tower), a semi-cylindrical latrine tower and a corner, four-sided, significantly rebuilt tower on the north-eastern side. Fortunately, the fourteenth-century arcades on the outer facade of the castle and the south-eastern tower survived. In the thicket of present buildings, you can still find relics of the outer ring of fortifications. Unfortunately, the castle is surrounded by modern skyscrapers, badly corresponding to the medieval buildings. Visiting the interior is not possible, although some interesting vaulted rooms and portals have been preserved.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Later Castles, London 2000.

Williams D., Gower. A Guide to Ancient and Historic Monuments of the Gower Peninsula, Cardiff 1998.