History

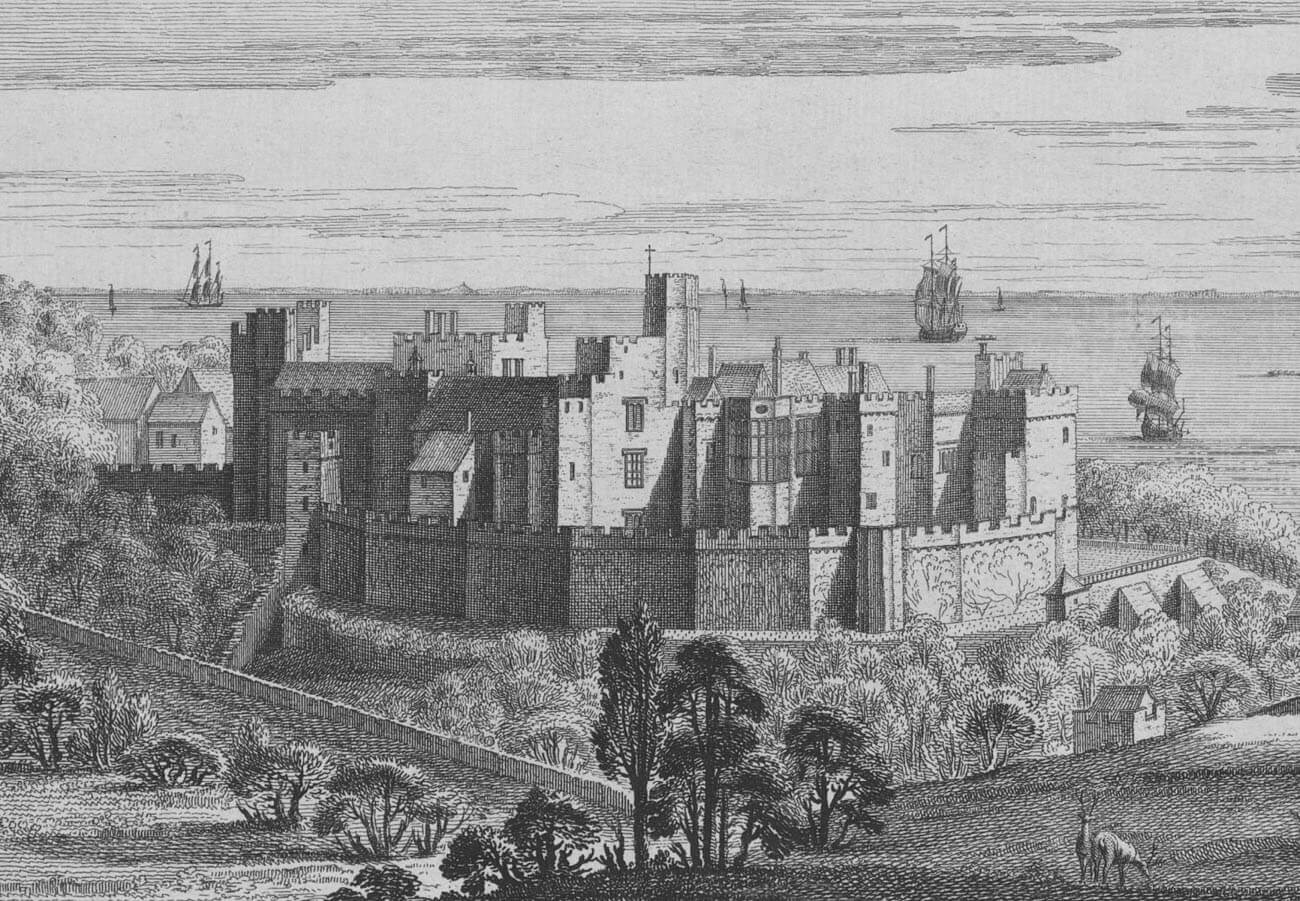

The first wood and earth castle in St Donats was erected in the early 11th century, during the Norman penetration of the lands of South Wales, although the oldest records about the local feudal duties survived from 1173 – 1183. Three families were associated with them: Butlers (Pincerna in Latin), de Marcross, and de Hawey. Of these, William Pincerna appeared the earliest in the Glamorgan region, recorded in 1130 on the charter of Neath Abbey. Pincerna name denotes the office of butler or cup-bearer to a superior lord, while Hawey was a territorial name derived from Halsway and Combe Hawey in Somerset. It is assumed that these two names in fact meant the one family who built St Donats at the beginning of the 12th century.

The oldest stone building of the castle (keep) began to be built at the end of the 12th century. Around 1233, the son of Simon de Hawey, William de Hawey, married the heiress of the Marcrosses, while Thomas de Hawey in 1233 opposed the rebellion of Richard Marshal, thus St Donats was briefly captured by the rebels. In the second half of the thirteenth century, the heirs of St Donats were Thomas de Hawey II, then John de Hawey, who died in 1287, and Thomas de Hawey III. When he died in 1298, the male line of the family expired. As a result, the castle became the property of the Stradling family, who came from Switzerland, by the marriage of Sir Peter Statelynge (Estratelinge) with Joan de Hawey. Sir Peter, his wife, and later her second husband John de Pembridge, enlarged the castle at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, fortifying the outer bailey and enlarging the keep and the gate of the upper ward. It is possible that these works were also carried out between 1316 and 1327 by the son of Peter Statelynge, Edward Stradling.

In 1321, Edward Stradling joined the rebellion of the nobility against the hated favorite of King Edward II, Hugh Despenser, for which his estates were confiscated and restored only in 1324. Edward’s son, Sir Edward Stradling II, was twice the sheriff of Glamorgan, and his wife, Gwenllian Berkerolles, belonged to the house holding the Coity Castle. Their son, William Stradling, at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, took an active part in political events in Glamorgan and Gower, but also took part in a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Another heir of St Donats, Sir Edward Stradling III, married the daughter of Henry VI’s uncle, Cardinal and Bishop of Winchester, Henry Beaufort. In 1423 he became the chamberlain of South Wales, and in 1438 the sheriff of Carmarthenshire. He was also tasked with fighting piracy in the waters of South Wales, which ironically ruined his later years. In 1449, his eldest son Henry and his family were kidnapped by Breton pirate Colyn Dolphyn on a voyage from Somerset to Wales. To free them for 1,000 marks, Edward was forced to sell some of his family’s estates. He died in 1453 on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and St Donats was taken over by his son Henry. Henry in the third quarter of the 15th century, or his successor Edward Stradling IV at the end of the 15th century, rebuilt a large part of the upper ward of the castle to improve living comfort.

In the first quarter of the sixteenth century, Sir Edward Stradling IV boasted two hunting parks in St Donats, for red deer and fallow deer respectively. He also rebuilt the north and west wings of the castle, where he died in 1535, giving way to Sir Thomas Stradling II, heir in the years 1535-1571. In the 1540s, he enlarged the family property by taking over the property of dissolved monasteries, but in 1551 he was imprisoned in the Tower of London due to court intrigues directed at against Edward VI. After regaining influence during the reign of Maria Tudor, in 1558 he was again imprisoned for two years, this time by Elizabeth I on suspicion of displaying the miraculous cross made of an ash trunk, torn during the great storm in St Donats in the Holy Week of 1559. Released in 1563, he probably spent the rest of his life at St Donats Castle. He was succeeded in 1571 by Edward Stradling V, who in the last quarter of the 16th century established a library in St Donats, which was said to be one of the best in Wales.

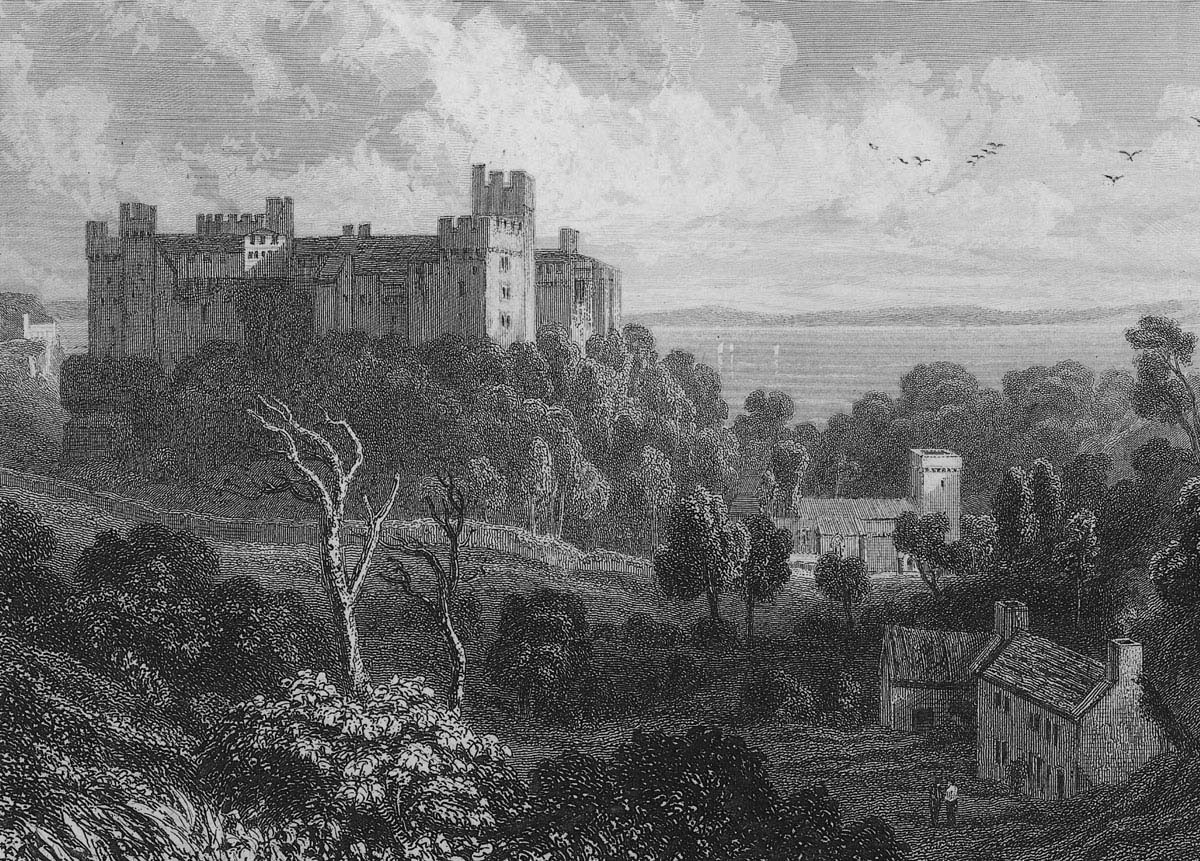

During the English Civil War, the Stradlings backed Charles I and for this reason the family lost its importance after war ended. However, they kept the castle in St Donats until the death of Sir Thomas Stradling, who was killed in a duel in France in 1738. The estate was inherited by his friend Sir John Tyrwhitt, with whom Thomas reportedly made a pact in which each promised the other his inheritance in the event of death. Under the rule of the Tyrwhitt family, the castle entered a period of long decline and gradually fell into disrepair. Partial restoration was started only after a hundred years by John Whitlock Nicholl Carne, who bought the castle in 1862. Unfortunately, these repairs partially destroyed the historical appearance of the castle. The next stage of the reconstruction took place in 1901-1909, when the new owner, Morgan Williams, carried out an extensive and more careful renovation, employing famous architects George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner. In 1925, the castle was bought by the millionaire William Randolph Hearst, who carried out another reconstruction. He made many changes, transforming the original parts of the castle and buying medieval architectural elements in Great Britain and France, and then installing them in St Donats (e.g. a painted wooden ceiling from a church in Boston, or a relocated roof truss from the refectory of the Bradenstoke Abbey from the beginning of the 14th century).

Architecture

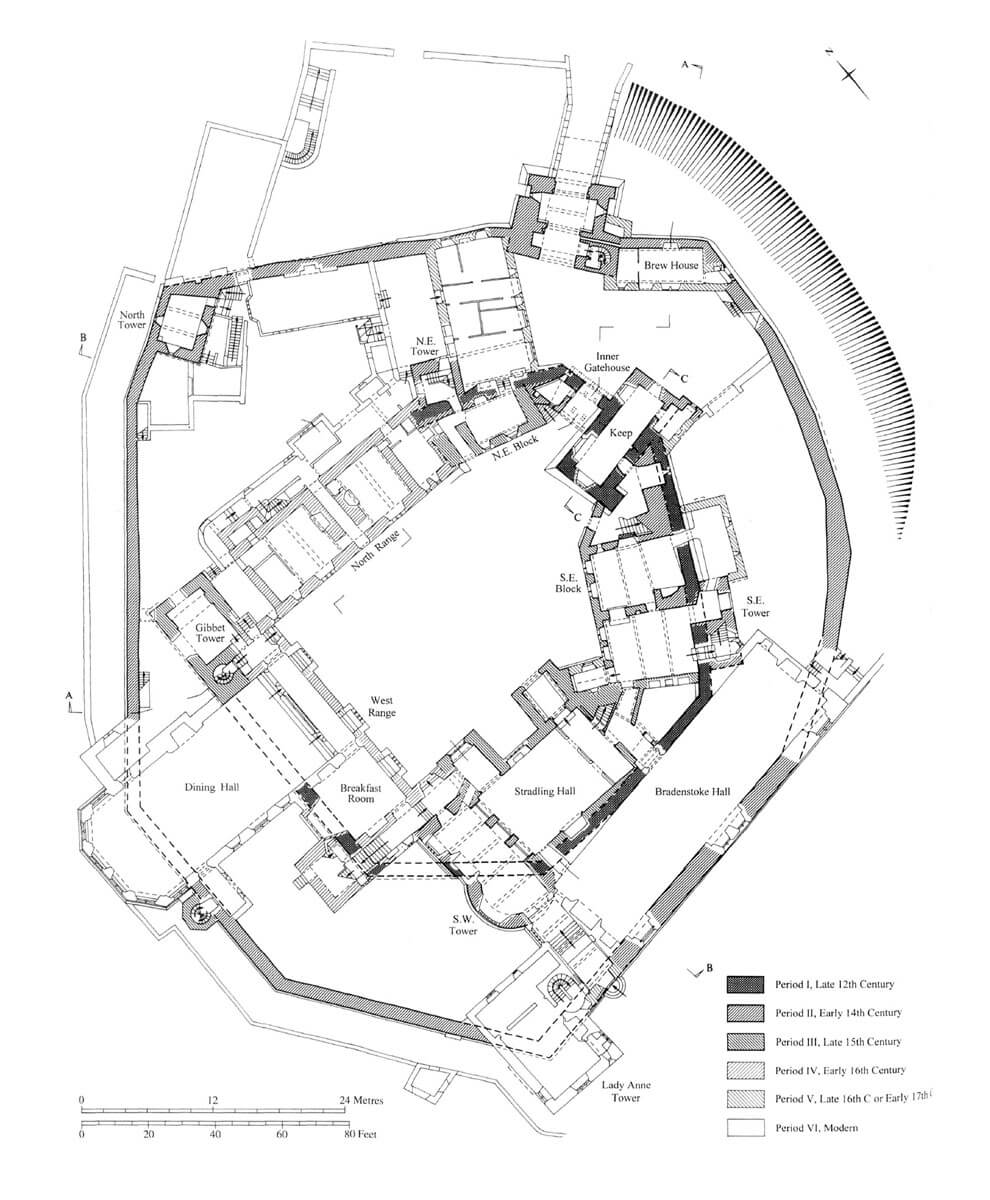

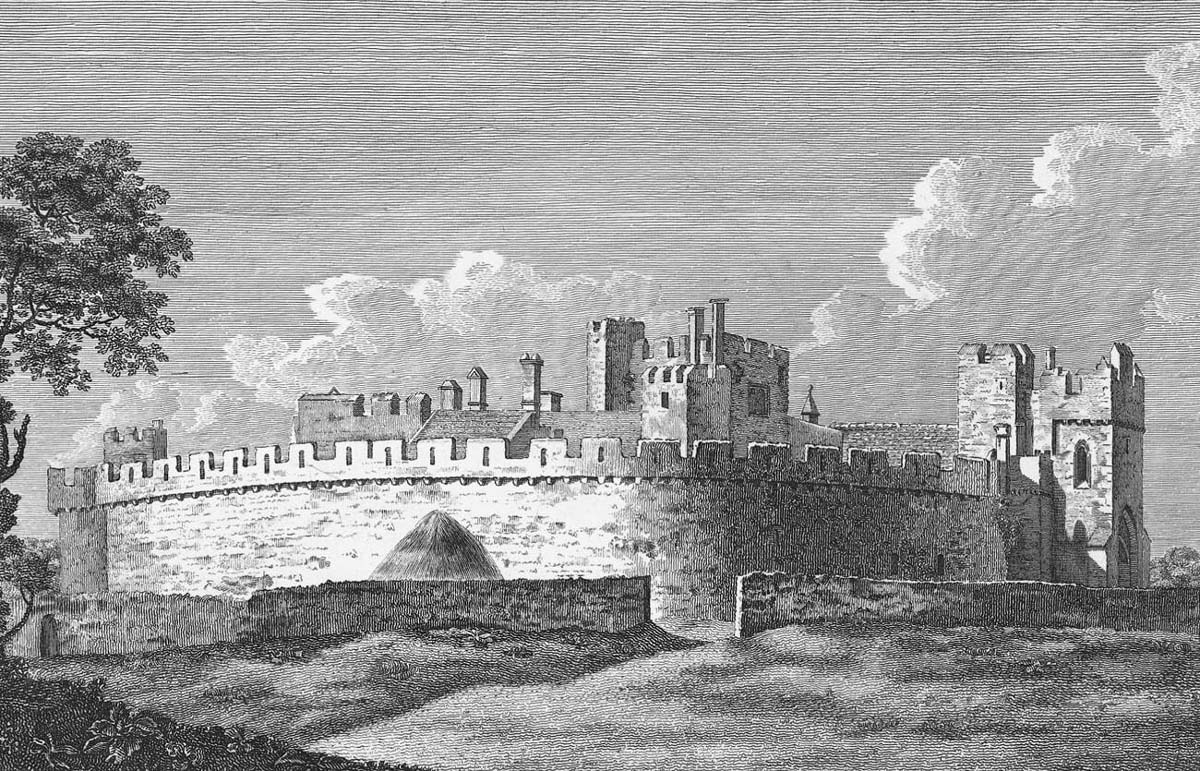

The castle was erected on a promontory of a hill with steep slopes on the west and north-west sides, in the eastern part of a narrow valley. From the west, the castle was surrounded by the small Llys Weirydd river, flowing a short distance to the south into the waters of the Bristol Channel. The southern part of the castle hill descended slightly more gently with a series of terraces, while the eastern side was the most accessible (it was secured with a ditch). In one of the bends of the river, in the valley at the foot of the castle hill, the parish church of St. Dunwyd was situated.

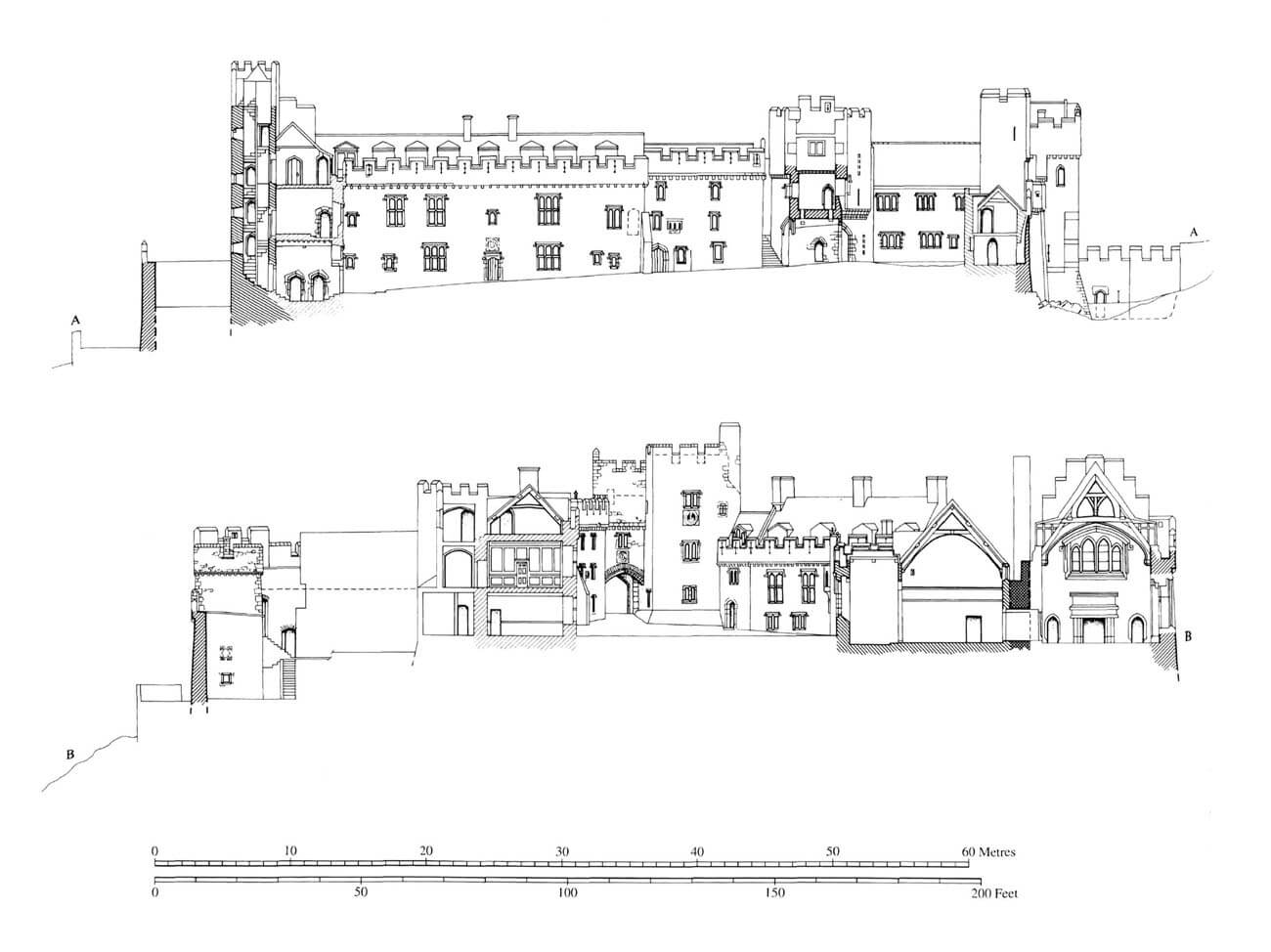

The original fortifications of the castle consisted of wood and earth fortifications, covering a roughly circular area with a diameter of about 50 meters. The courtyard it created was one of the largest in Glamorgan. At the end of the 12th century, the initial palisade was replaced by a stone defensive wall about 1.2 meters thick and 4.6 meters high (to the level of the wall-walk), which surrounded with short, straight sections a polygonal courtyard measuring approximately 50 x 55 meters. The gate, a plain passage, 1.8 meters wide, created in the wall, was located in the north-eastern part of the perimeter. It was adjacent to the south by a massive tower – keep (today called the Mansell Tower), built on a rectangular plan with dimensions of 10 x 6.5 meters, almost entirely placed inside the perimeter, at the courtyard. A ditch was dug in front of the gate, through which a drawbridge was probably placed.

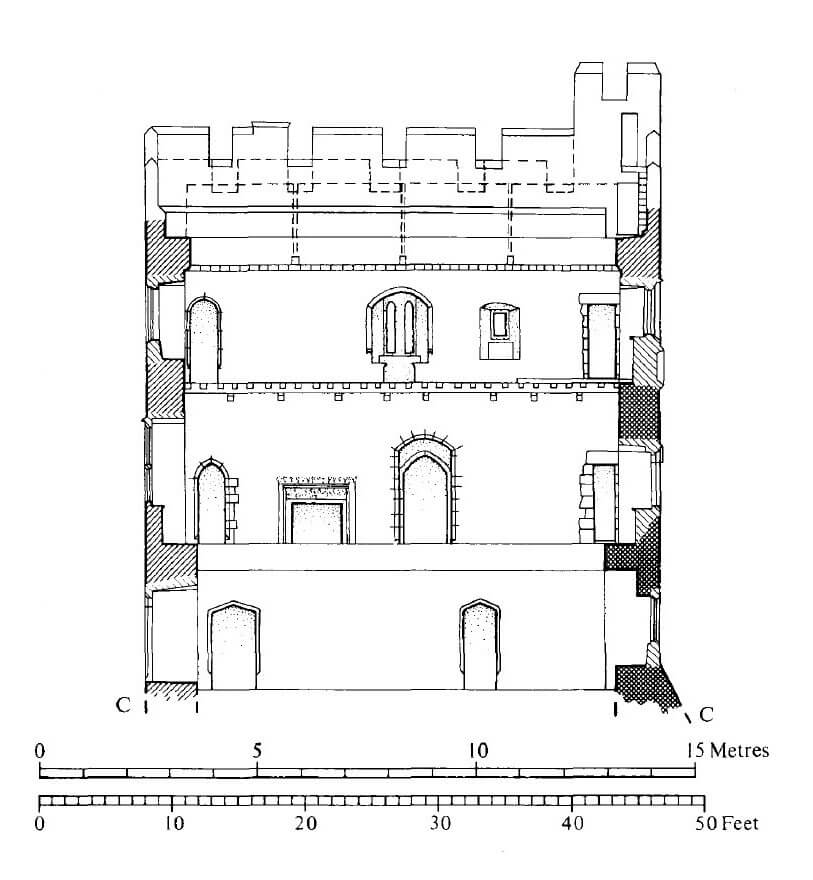

The entrance to the keep was originally from the south, through a portal on the first floor, to which timber stairs were attached, easy to remove in case of an danger. The keep had three floors: an economic warehouse on ground floor, a residential and representative first floor, and a private living room on the second floor, accessible by a spiral staircase located in the south-west turret. Only a hatch pierced by a wooden ceiling and a ladder led down to the unlit ground floor. The first-floor chamber was heated by a fireplace, decorated with leaf motifs growing from the central mask on its lintel. Like the ground floor, it was covered with a timber ceiling mounted on stone consoles. At the narrow portal of the staircase, there was a stone basin with an outflow directed through the walls into the corner between the keep and the stair turret. A similar basin was also placed at the portal on the second floor. The staircase led above the second floor, to an open defensive gallery, hidden behind a battlement.

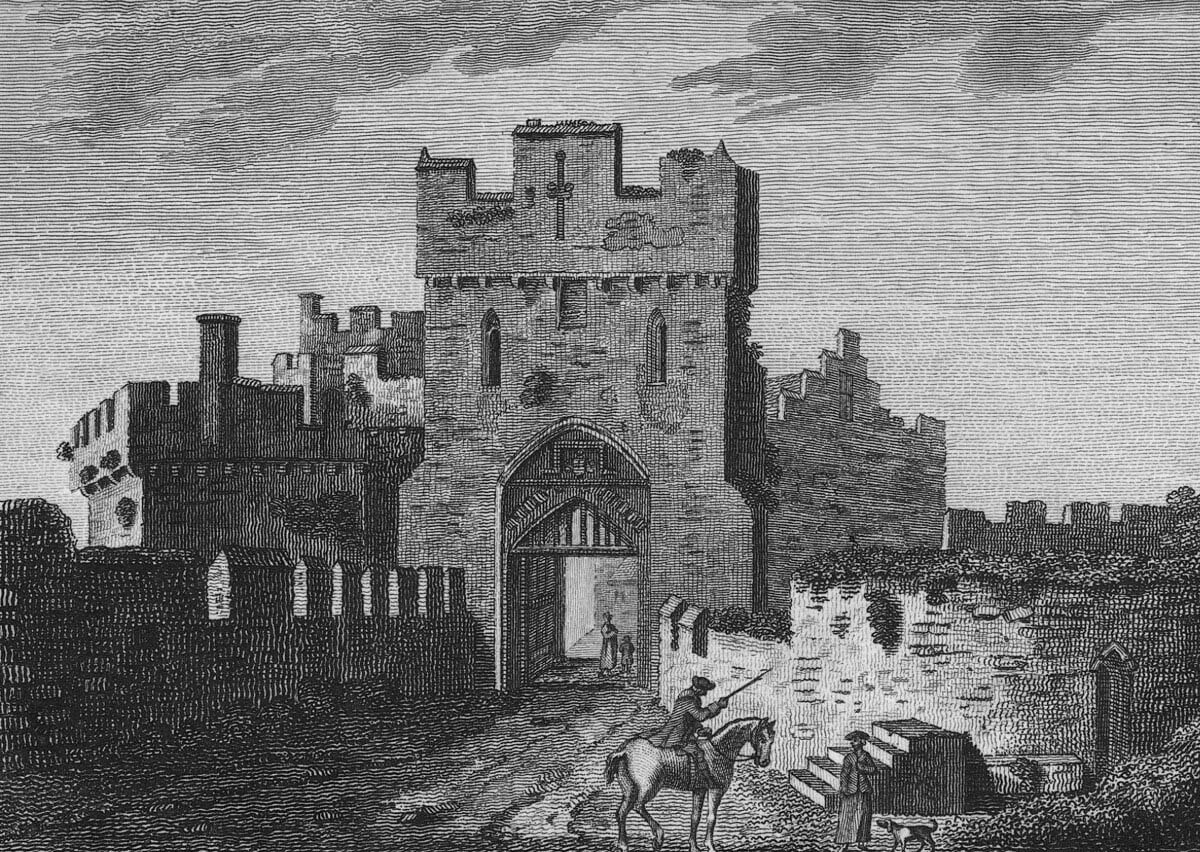

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, a defensive wall of the outer bailey was erected with a gatehouse on the eastern side and a quadrilateral, irregular tower inserted in the northern corner. The outer bailey was unusual, instead of creating a separate courtyard in front of the main part of the castle, it surrounded the entire older ward with its wall, creating a 10-14 meter wide zwinger. It also required backfilling the old ditch. The new, external wall was equipped with a parapet with merlons equipped with arrowslits, mounted on corbels protruding from the face of the walls. The entrance to the outer bailey was provided by the gatehouse, located in the north-eastern part of the perimeter. It had a passage in the ground floor, closed with a portcullis and a drawbridge, and an upper room accessible by a southern spiral staircase, which passed into the form of a watchtower, higher than the battlement of the gatehouse. On the opposite side, a similar turret housed a latrine serving the first floor. The room with the mechanism operating the portcullis was illuminated from the field side by two lancet windows with trefoils, above which the centrally located merlon was pierced with a cross-oillet. There were no guard rooms on the sides of the gate passage. In front of the gate there was a ditch, in the 16th century filled with a causeway closed with side walls above a small chamber, which was accessed from a ditch through an entrance in the side wall.

In the early years of the fourteenth century, fragments of the upper ward were also expanded, with the keep at the head, which was extended towards the north-east side, to the area of the outer bailey. In addition, a new, pointed, chamfered portal was created at the level of the first floor, shifted more to the east than the original one, accessible by external, stone stairs and closed with draw-bar. Several early Gothic windows were also inserted, and in the next stage a small latrine turret was built, pressed to the south-eastern corner. The new part of the keep did not receive the characteristic battered plinth that had the walls from the end of the 12th century.

The south-west corner of the inner ring of the wall was strengthened by the only semi-cylindrical tower in the castle, with a diameter of about 8 meters. Four-sided tower was added on the south-east side, and a third, also quadrilateral tower, on the north side. All of them were put in front of the curtains from the end of the 12th century. On the other hand, the gatehouse of the upper ward was treated differently, built entirely on the inner side of the perimeter, attached to the old keep. In its ground floor there was a vaulted gate passage, closed with a portcullis raised to the room on the first floor. The moulded portal of the passage as topped with a segmental arch. Inside, the vault was pierced with four murder holes, while in the northern wall there was a passage to a small guard’s room, tucked into the corner of the defensive wall. This room was equipped with a arrowoslit in the eastern wall. A room on the first floor of the building probably had a similar arrowoslit, but in the 15th century a late Gothic, cinquefoil window was inserted in its place. The gatehouse was crowned with a parapet with machicolation.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, the residential and representative area of the castle was enlarged, as a result of the erection of a hall (Stradling Hall) at the upper ward. It was located in the southern part of the courtyard, on a rectangular plan with dimensions of about 12 x 8 meters, with an entrance located on the courtyard side in the porch and with a second similar, four-sided avant-corps connected by a corner with a small, older building from the 14th century. The porch with two side, stone seats inside, led to the passage vestibule, separated by the partition wall from the hall, which protected the main room against drafts and in which the servants could stay. The hall was also connected with the kitchen, originally located in the outer bailey, behind the curtain of the wall from the end of the 12th century, and with the stairs leading to the porch upper floor, from where it was possible to go to the balcony over the hall, traditionally intended for musicians. In the hall, the Lord’s table stood on a dais in the western part, where from the south the heating was provided by a fireplace, and the lighting came through a large, three-light window with a four-sided jamb, embedded in the north-west avant-corps, and a three-light tracery window set in a recess with side seats in the northern wall. The large space of the hall was covered with an open roof truss, above which the walls of the building were topped with a battlement mounted on corbels. As early as the 15th century, the parapet was only decorative. On the west side, at the back of the semicircular tower, there were private rooms, to which lord could withdraw from the hustle and bustle of feasts and celebrations in the hall.

In the second half of the 15th century, a four-sided Gibbett Tower was also built in the north-west corner. It received four floors connected by a spiral staircase embedded in the communication turret adjacent to the south. Subsequently, in the fifteenth century, north-east wing was built near the gate and south-east wing adjacent to the keep. The latter filled the entire space up to the hall building, to which it was located at an angle. It had two floors, each with two four-sided chambers and one triangular room connected with the keep. Its façade from the side of the courtyard was characterized by a decorative parapet with battlement and large, four-sided windows. The north-east wing was relatively small, three-story, topped with battlement, similar to the buildings on the opposite side of the courtyard. Each storey housed one chamber, illuminated with single, arched windows and a passage on the ground floor connected with the north-east tower. In the outer bailey, the works from the end of the 15th century were limited to the building of a polygonal turret with a staircase, protruding in front of the western curtain.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the west wing and the chambers of the northern wing were built. They were added at right angles to the Gibbett Tower, so that the whole was in the shape of the letter L. The northern wing from the side of the outer bailey received a small, four-sided projection, and the west wing a slightly larger annex at the corner. The latest defensive structure, erected at the end of the Middle Ages, was the Lady Anna Tower, located in the south-west corner of the outer defensive wall.

Current state

The castle has survived to modern times, but its appearance is the result of numerous transformations, unfortunately also modern ones, as a result of which most of the outer bailey was built with new rooms, such as the Dining Hall on the north-west side, or the Bradenstoke Hall in south side, erected on the zwinger area in order to place in it a medieval roof truss, transferred at the beginning of the 20th century from the Bradenstoke Abbey (its insertion required the removal of modest but older utility rooms). On the south-west side in the 1930s, the 16th-century Lady Anna Tower was demolished, replaced with a new, larger structure, a number of early modern buildings were also created in the northern part of the outer bailey, and the gatehouse of the upper ward was raised in the 19th century. The changes are also manifested in the new, large windows of older buildings. Currently, the owner of the castle is the private Atlantic College, but visiting is possible on certain days and times.

bibliography:

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Later Castles, London 2000.