History

Abbey of St Dogmaels was founded in 1113 for thirteen monks brought from the French monastery of Tiron. The founders were Robert fitz Martin and his wife, Maud Peverel. In 1120, Abbot William of Tiron agreed to Martin’s request that the prior of St. Dogmaels be transformed into an abbey, but still subordinate to his native monastery from France. Its first abbot was Fulchard, elected by Bishop Bernard of St Davids, who was to visit Tiron at least once every three years to maintain strong ties between the two religious houses.

In the first years of existence, the abbey was exposed to numerous dangers, as the lands on both banks of the Teifi River often changed hands during the Welsh-English conflicts. In 1136, the Anglo-Normans of Robert Fitz Martin were defeated in the nearby Battle of Crug Mawr and forced to withdraw. Two years later, the village and abbey of St. Dogmaels were plundered by the sons of Gruffudd Ap Cynan, Owain Gwynedd and Cadwaladr, and in 1165 the Welsh ruler Lord Rhys banished the monks from the nearby monastery in Cardigan. Despite the wars, the construction of the monastery progressed throughout most of the 12th century and had to be advanced, since in 1188 the abbey was visited by a famous monk, chronicler and writer, Gerald of Wales, who, along with Baldwin, the archbishop of Canterbury, was collecting support for the Third Crusade, during his trip around Wales .

In 1198, the abbey was put into the dispute over the election of the new bishop in St Davids after the death of Peter de Leia. The new candidates were Gerald from Wales and Walter, abbot of St Dogmaels, but the latter was disqualified by the lack of literacy skills. Both were initially rejected by Archbishop of Canterbury, although Geralt was elected by the local cathedral chapter. An angry archbishop, who did not want to fill the post with a Welshman, nominated Walter of St Dogmeals for the bishopric. The dispute reached all the way to Rome. The Pope finally rejected both candidacies and forced the election of a new bishop in 1203.

The mid-thirteenth century was a period of prosperity for the abbey, related with closer control of the surrounding lands by the Anglo-Normans and the reconstruction of the castle in nearby Cardigan around 1240. At that time, the construction of the nave of the monastery church was completed, cloisters were erected in the mid-thirteenth century, and at the end of the thirteenth and at the beginning of the fourteenth century, most of the monastery buildings, the infirmary and the chapter house were erected. In 1291, the abbey’s income was valued at £ 58, indicating its average size by Welsh standards (by comparison, the poor priory in Cardigan was valued at only £ 16).

In the fourteenth or fifteenth century, a significant part of the west wing of the abbey was rebuilt to provide better living conditions for the abbot and his guests, but during this period the monastery began to fall into debts. The abbot sent complaints to King Edward as early as in 1296 and 1317 complaining about the war desolation and too high taxes. The abbey also had problems with attracting new members, especially since the mid-fourteenth century, when Black Death hit Wales, shrinking the number of monks in the monastery. St Dogmaels never fully recovered from the epidemic. During the episcopal visit from 1402, it was found that only four monks, including the abbot, lived in the abbey. Moreover, they were criticized for their gluttony, not following the monastery rule, drunkenness and contacts with women.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the situation of the abbey improved slightly. The ruined church presbytery was renovated, the northern transept rebuilt in late gothic style, and the number of monks increased to six. Despite the gradual and slow improvement, due to the progressive Reformation, in 1536 the abbey was dissolved, like all other monasteries in the country, which according to Henry VIII’s order did not achieve an annual income of more than £ 200 (St Dogmaels had only £ 87 annual profit). Only eight monks and an abbot William Hire lived in the monastery at that time. Most of the abbey was rented to John Bradshaw of Presteigne in Radnorshire, who built a residence within it. For its construction, he used stones from the monastery buildings, which contributed to its rapid fall into total ruin.

Architecture

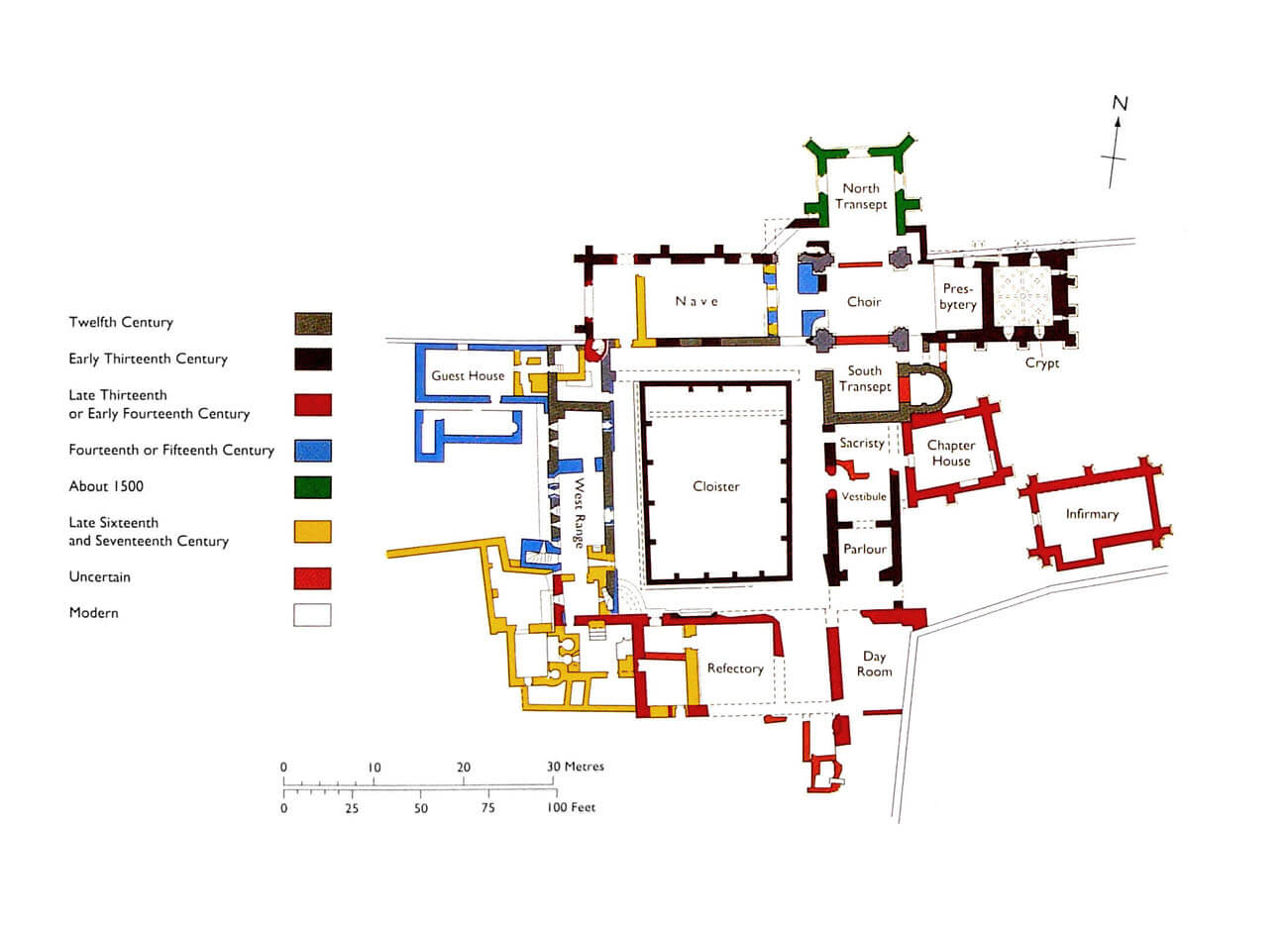

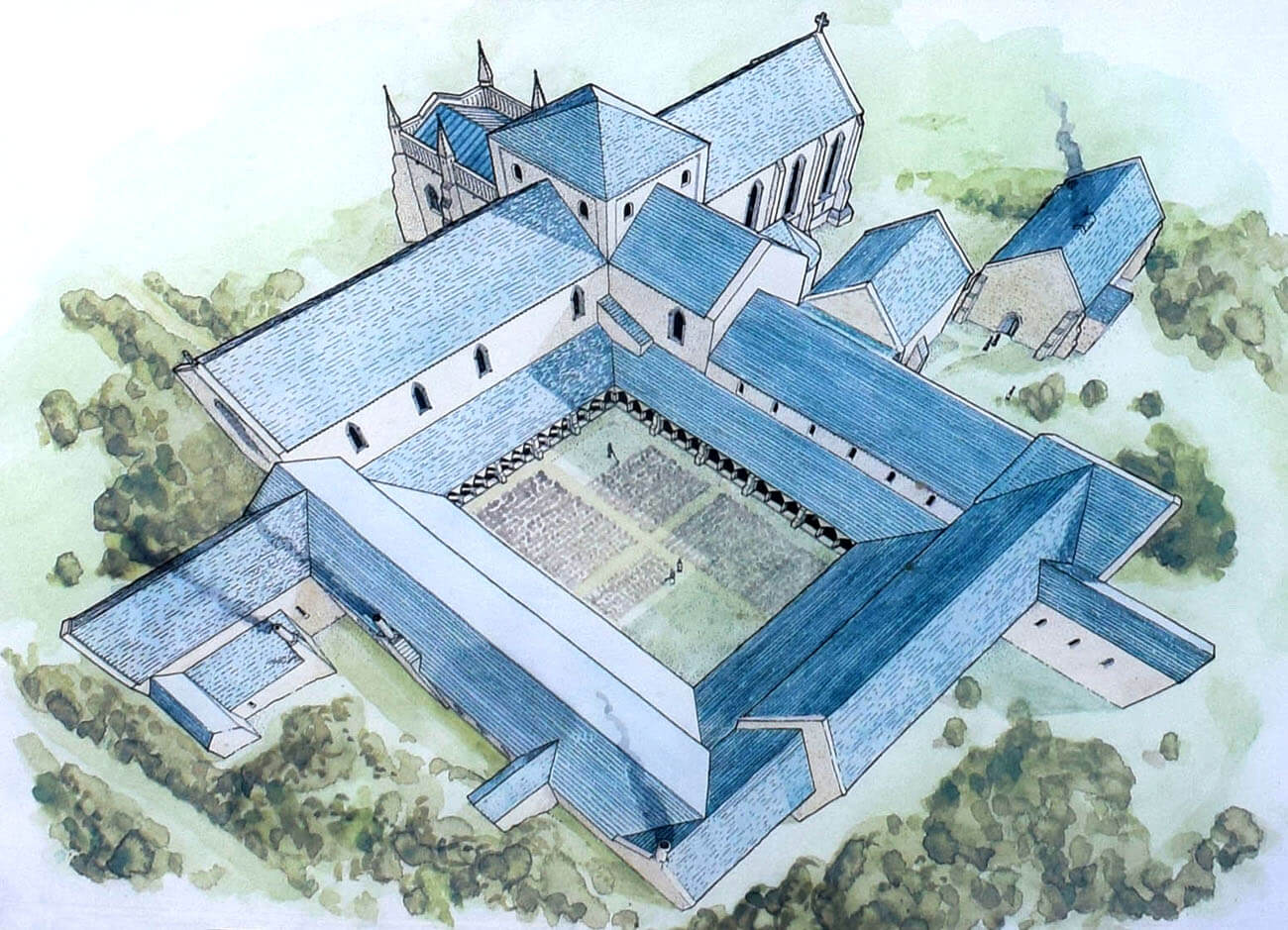

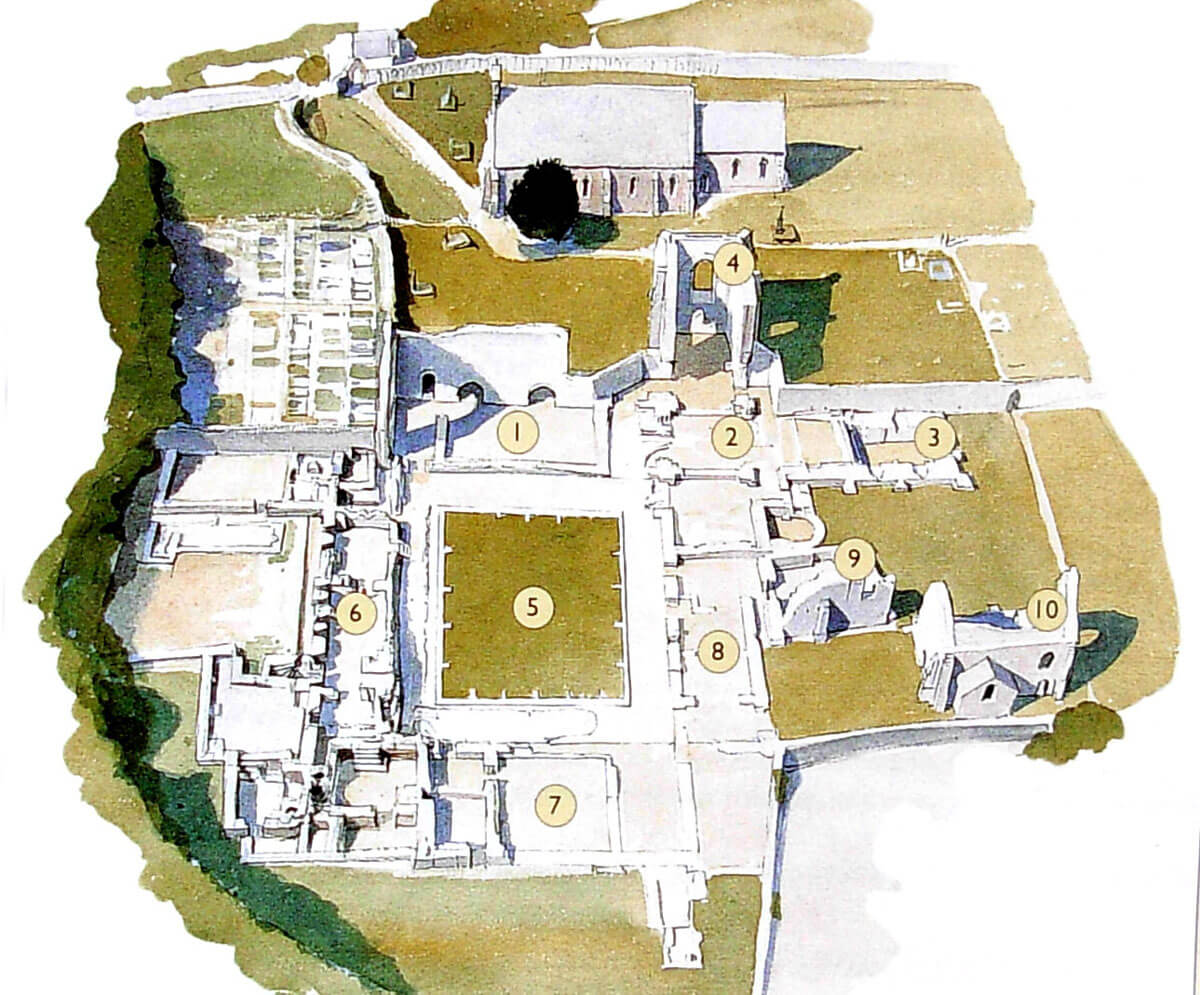

The abbey was founded west of Cardigan at the mouth of the Teifi River into the Irish Sea. It was located among meadows and fields, separated by a small stream flowing from the narrow valley to the south. The monastery area sloped slightly to the east and north-east towards the Teifi, and rose rapidly just behind the monastery to the west. The complex consisted of a church and adjacent claustrum buildings from the south, grouped around a quadrangular cloister. At a short distance from the claustrum rooms were the utility and economic buildings, as well as the infirmary, which required an isolated location.

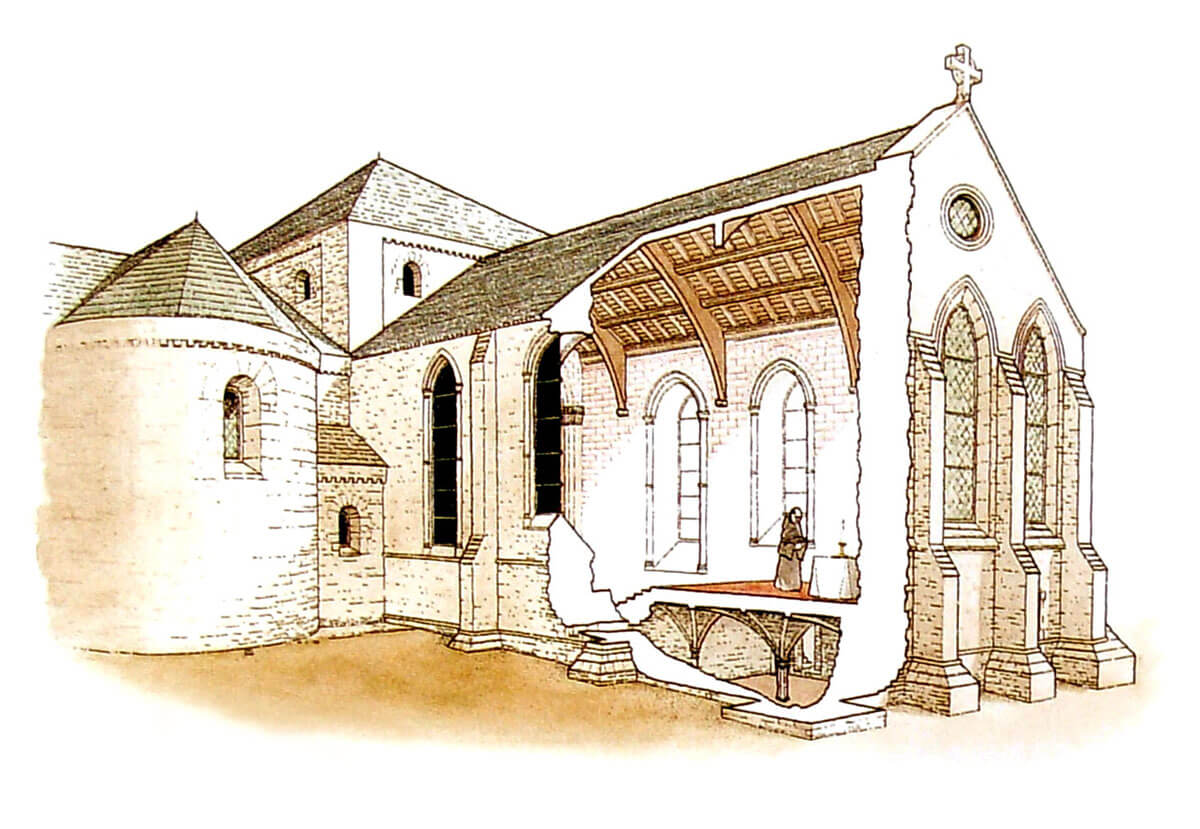

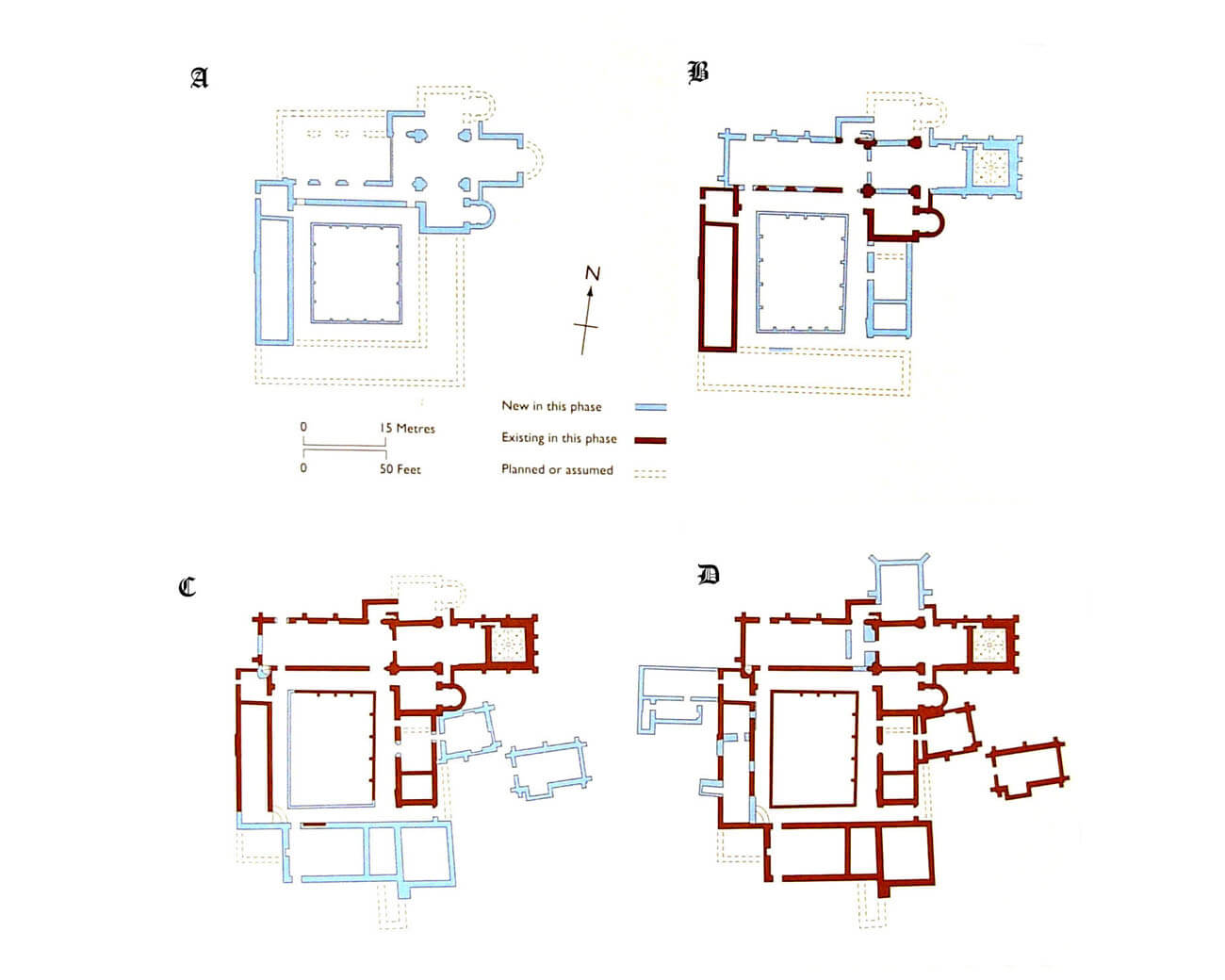

The church was initially planned to be erected as a structure based on a Latin cross plan with a three-aisle nave and a short four-sided chancel, probably ended with an apse in the east. The apse chapels were also to be located on both arms of the transept, and a four-sided tower was to be located above the crossing of the naves. Of these plans, only the chancel, southern transept, low tower, eastern bay of the nave and partly the southern aisle were able to be implemented in the 12th century. The church nave was completed in the first half of the 13th century, but in a significantly simplified, one-nave form, the previously erected southern aisle was transformed into the northern cloister, and the new nave was slightly extended to the west. The nave was quite unusual, because it did not have a western entrance portal, probably due to the nearby slope, which did not give much space. The entrances were located on the north-west and south sides, from where one could get to the cloisters. Near this portal, in the corner of the church, stairs were also leading to the attic above the nave or to the abbot’s rooms. The northern wall of the nave, apart from one four-light window, did not have more window openings, while in the fourteenth century a new ogival window with rich tracery decoration was inserted in the western facade. Originally, the floor of the nave was lined with stone slabs, in the 15th century replaced by smaller tiles. In its eastern part there was a stone rood screen with a portal in the middle, separating part of the church accessible to lay people from the part accessible only to monks. The top of the rood screen was reachable through a spiral staircase in the north-west part of the crossing of the naves. In this place, under the church tower, there was a choir of monks with stalls blocking the passage to the north and south transepts.

In the first half of the 13th century, the chancel of the church was extended by two bays, under which a crypt, unusual for Welsh monastic churches, was placed, probably intended for storing relics. Thanks to this, the main altar was placed on a 60 cm elevation, reached by a few steps. The square-shaped crypt was accessed by stairs in the northern part of the chancel. It had thick walls lit by slit windows on three sides, a series of small niches for setting candles, a rib vault supported by a central pillar and wall-shafts springing from the floor in the corners and from the middle of each wall. The chancel was probably covered only by an open roof truss or a wagon roof. Its lighting was provided by tall pointed windows, in the eastern wall probably creating a triad divided by the buttresses. From the outside, both the chancel walls and the buttresses were clasped by a chamfered plinth.

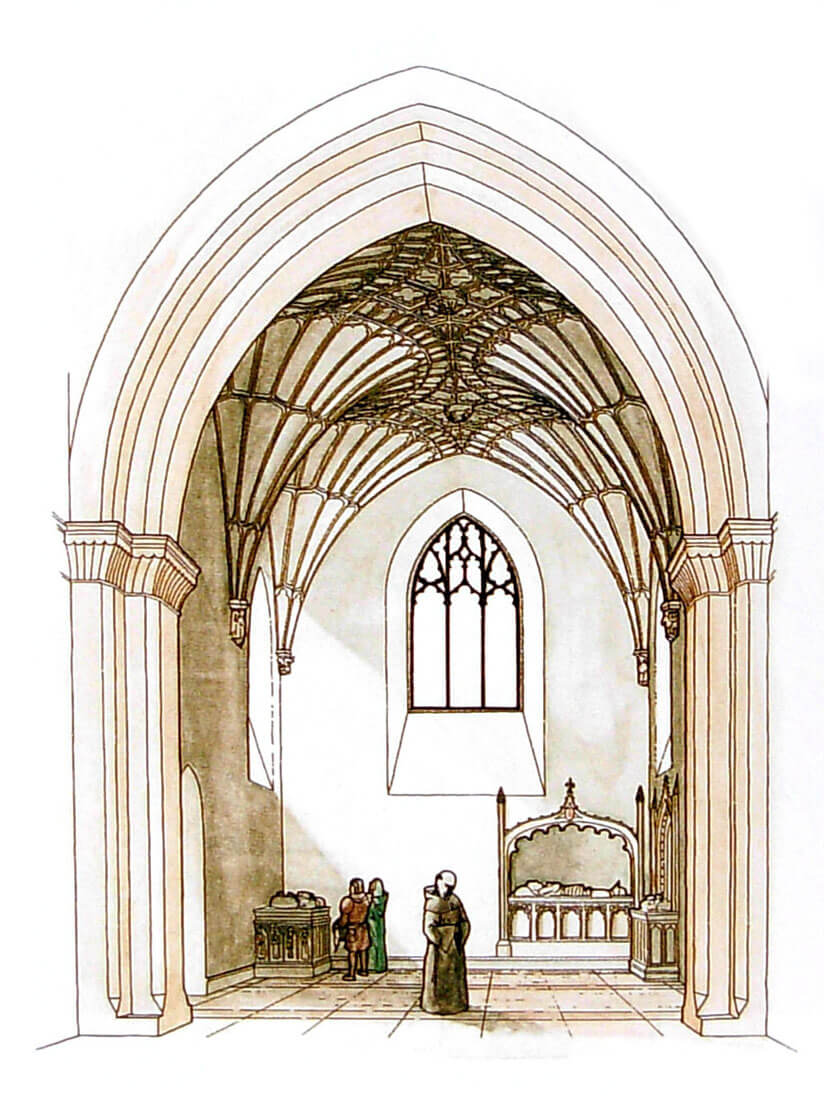

The last change in the church’s appearance was the late-gothic rebuilding of the northern transept from the beginning of the 16th century. Thanks to the strengthening of its walls from the outside by buttresses, it was possible to install a stone vault inside and to open a large ogival, four-light window in the northern wall and smaller three-light windows in two side walls. The sophisticated rib vault rested on corbels carved, among others, in the shape of angels and a lion. The northern transept, like the southern one, served as a passage, connecting the nave with the chancel, due to fencing of the central part of the church by monks’ stalls.

The inner courtyard surrounded by cloisters adjoined the southern wall of the church nave. Its central garth originally served as a garden where herbs and vegetables grown, while by the cloisters could get into most of the monastery buildings. It were covered with mono-pitched roofs based on ogival arcades and columns, connected by two by single capitals. On the side of the cloister, a buttress was placed every three arcades. They were to create a regular division into five bays on each side, which could have been changed in the first half of the 13th century, after a slight extension of the cloister to the area of the unbuilt southern aisle of the church.

The oldest monastery rooms from the turn of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were located in the west wing, where dormitory was probably initially located on the first floor and in the northern part of the ground floor the so-called a parlour – a room in which brothers could contact lay people. The main room of the west wing on the ground floor level housed a monastery pantry and was illuminated from the west by a series of narrow windows. In the fourteenth or fifteenth century, a perpendicular building was added to the west wing, with guest rooms and the abbot’s private chambers (including one warmed by a fireplace) and a chapel on the first floor.

In the southern wing from the end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century, there was a refectory in the middle. In front of its entrance portal there was a lavatory in the form of a stone bowl, intended for washing hands before meals. In the western part there was probably a kitchen, the interior of which was filled with three oval ovens. On the eastern side the refectory could have been adjacent to the calefactory, the only heated room in the monastery apart from the kitchen and the infirmary. In the extreme eastern part of the building there was a so-called day room, i.e. a room intended for work. Just in front of it, a latrine block protruded from the compact development of the wing, situated in such a way that its drain outlets were directed towards a stream flowing nearby. The latrines were probably connected on the first floor with the dormitory in the eastern wing.

The 13th-century east wing had two floors. The first floor probably housed the monks’ bedrooms – the dormitory (connected by the so-called night stairs with the church transept and the so-called day stairs with the cloister), while on the ground floor from the north, the sacristy, the parlour, followed by a passage to the infirmary, which was built at the end 13th century in a separate, detached building. At the end of the 13th or beginning of the 14th century, a chapter house was also built, added to the eastern wing. The brothers gathered there daily to consult on monastery matters and read the order’s rule. It was situated unusually, with a deviation from the transverse axis of the wing, which may have resulted from the desire to leave a passage in front of the infirmary. On the outside, the chapter house was reinforced with buttresses, while inside, wide pointed recesses were placed in three walls. The entrance to the infirmary led from the west through a pointed portal. The corners and the northern elevation were supported by buttresses, placed perpendicularly and parallel to the axis of the building. In addition, a shallow, vaulted projection protruded from the southern elevation.

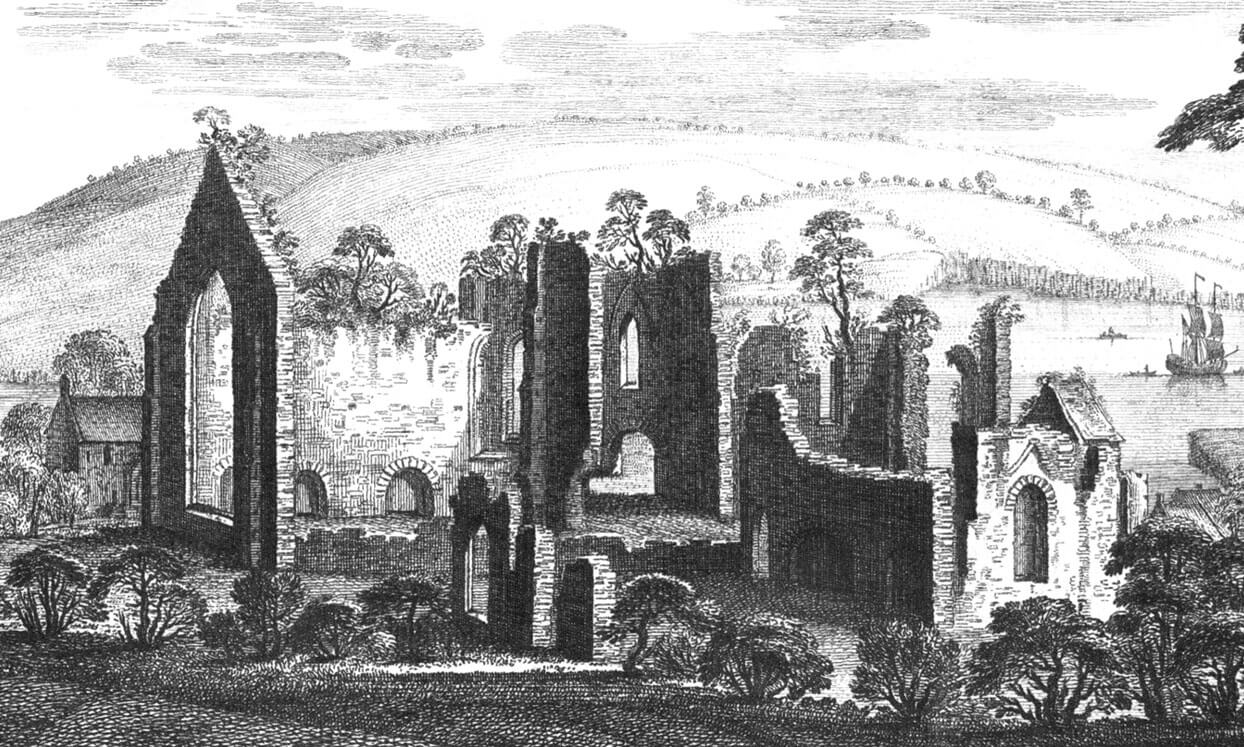

Current state

Only ruined fragments have survived from the abbey buildings and the church. The northern and western walls of the nave, the northern transept, the fragment of the chapter house and the ruined infirmery building survived. Partially preserved is the crypt under two eastern bays of the presbytery and floor tiles from the fifteenth century on large areas of the nave. The remaining part of the abbey is outlined only by the low ground walls and foundations. The monument is under the protection of the Cadw government agency and open to the public. On the north side, the parish church of St Thomas is a Victorian neo-Gothic structure, built using part of the stones from the ruins of the abbey.

bibliography:

Burton J., Stöber K., Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, Chippenham 2015.

Hilling J., Cilgerran Castle, St Dogmaels Abbey, Cardiff 2000.

Pritchard E., The history of St. Dogmaels Abbey, London 1907.

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

Vaughan H.M., The Benedictine Abbey of St. Mary at St Dogmaels, “Y Cymmrodor”, 27/1917.