History

According to tradition in the middle of the 6th century, Saint David came from Ireland to the westernmost peninsula of Wales. He founded an early medieval monastic community, at which a settlement grew over time, called Menevia then, and later named after the founder. Between 645 and 1097, St Davids was repeatedly attacked, among others by the Vikings, but after some time, the monks always returned and rebuilt the monastery. During the raids two bishops were killed by the attackers: Moregenau in 999 and Abraham in 1080. Despite this, St Davids became such an important religious and intellectual center that in the ninth century King Alfred called upon the religious community of St Davids for help in rebuilding the intellectual life of the kingdom of Wessex.

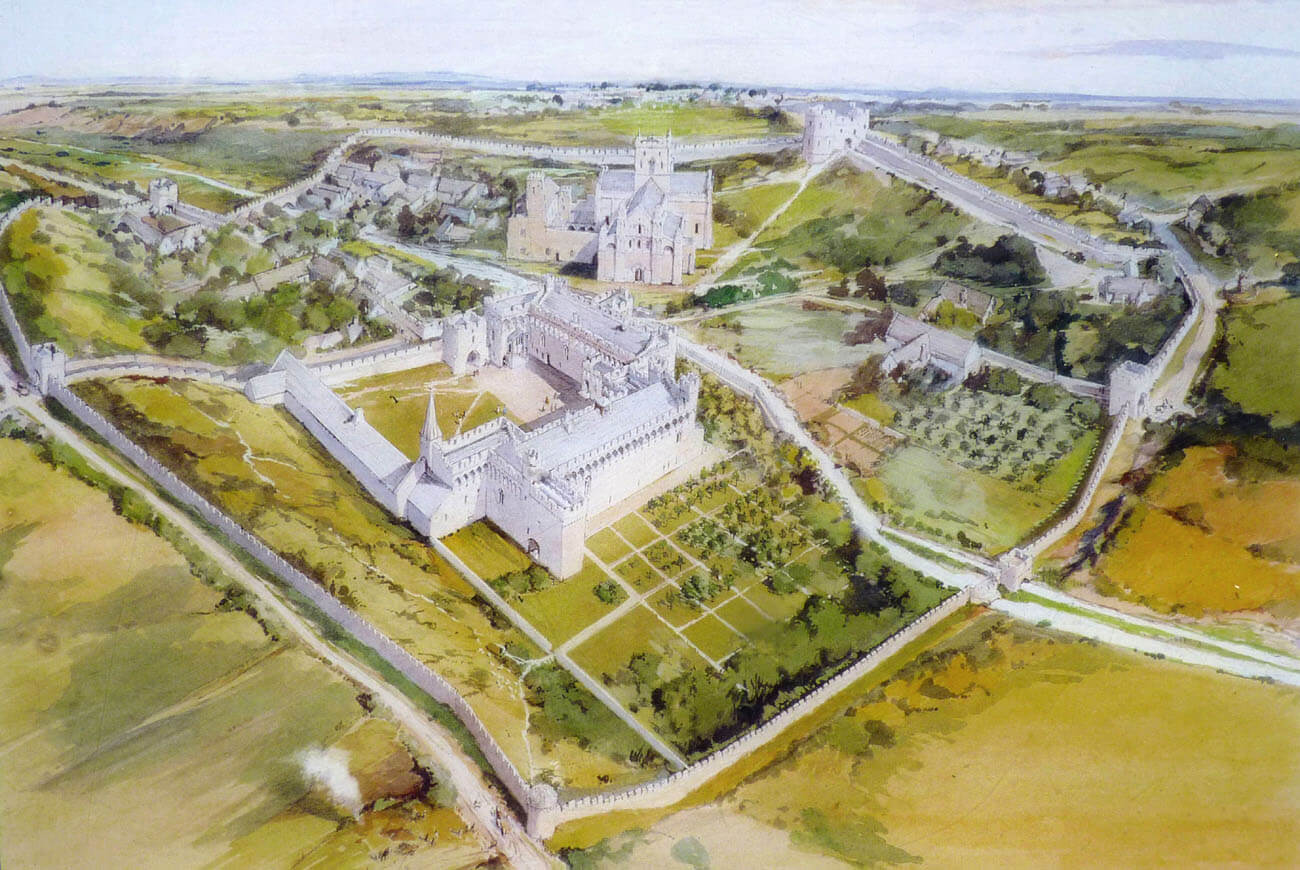

In 1081, St Davids was visited by King William the Conqueror, possibly to investigate the strategic advantages of the settlement due to its proximity to Ireland. It was also not without significance that in the same year the meeting in St Davids was also organized by King of Gwynedd, Gruffydd ap Cynan, Bishop Sulien and the South Welsh ruler Rhys ap Tewdwr. Soon after, in 1093, the Normans took over the monastery and founded a bishopric. Its income was guaranteed by pilgrims, after in 1120 St. David was canonized, and the Pope recognized that a twice visit to St Davids was a spiritual equivalent of a visit to Rome. This happened despite the inability to find the remains of Saint David and, consequently, the lack of a relics (the alleged tomb of Saint David was not found until 1275). In 1115, King Henry I appointed Bernard, former Chancellor of Queen Mathilda, as a local bishop, who in 1123 obtained from Pope Callixtus II the privilege to establish a pilgrimage center in St Davids. He also began the reform of the monastic community, by appointing a chapter in place of the semi-monastic canons called clas in Wales, and began building of the cathedral, which was consecrated as early as 1131. Bernard only has failed to establish a separate Archdiocese of Welsh because of the opposition of the King and Archbishop of Canterbury.

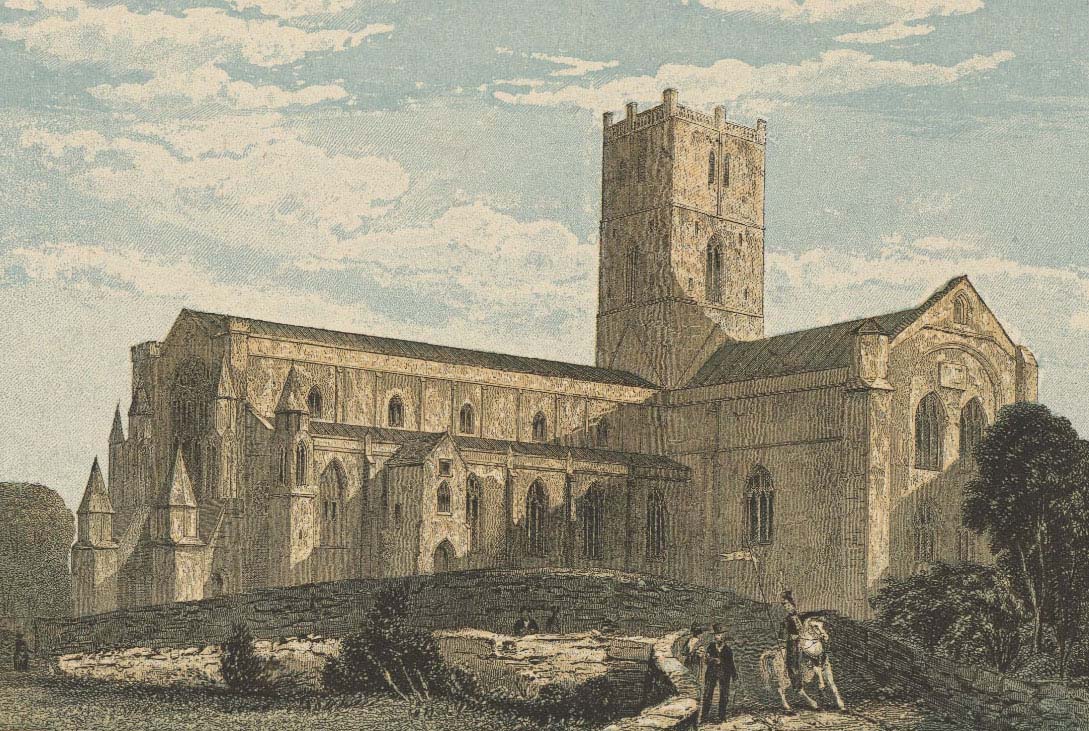

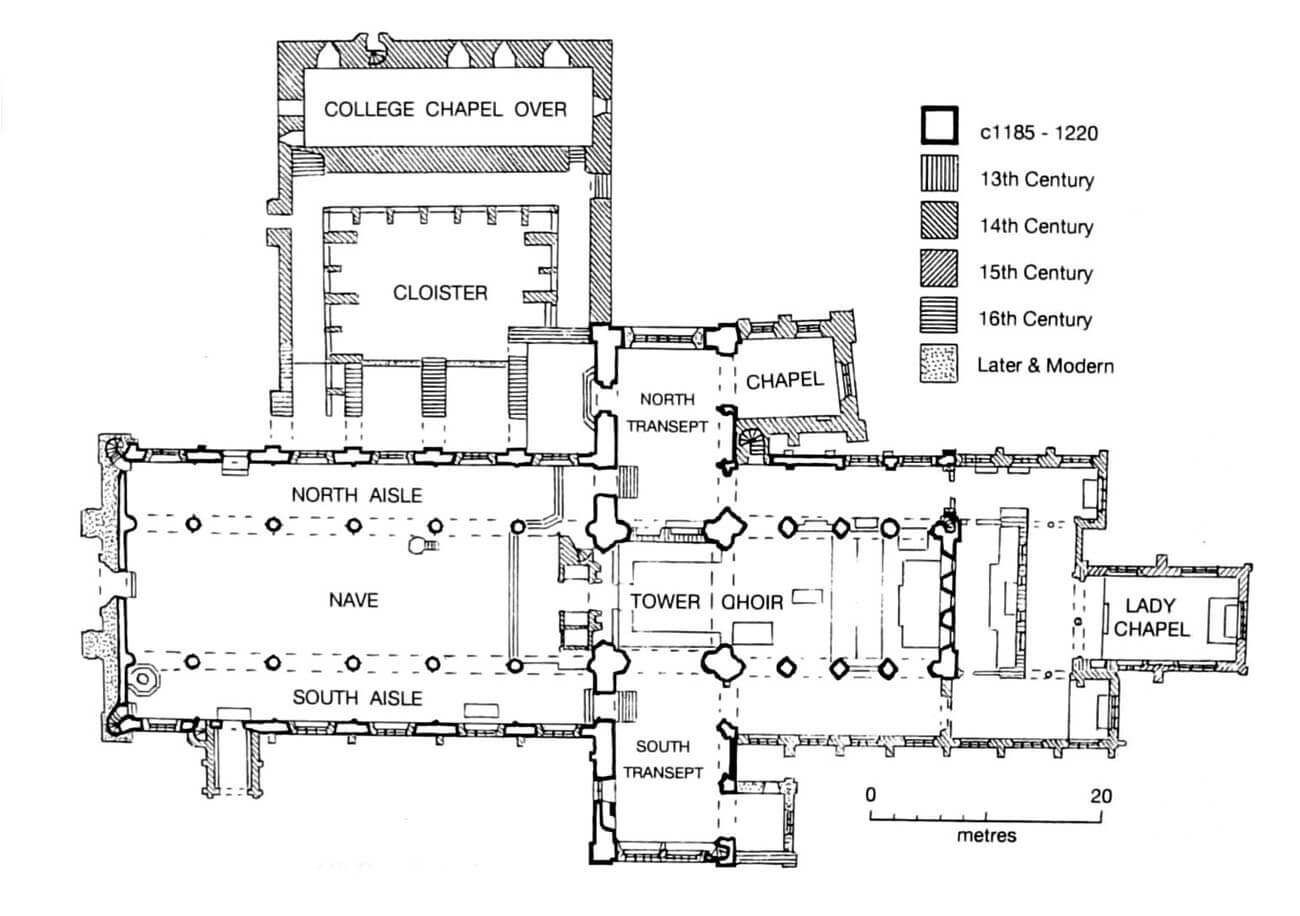

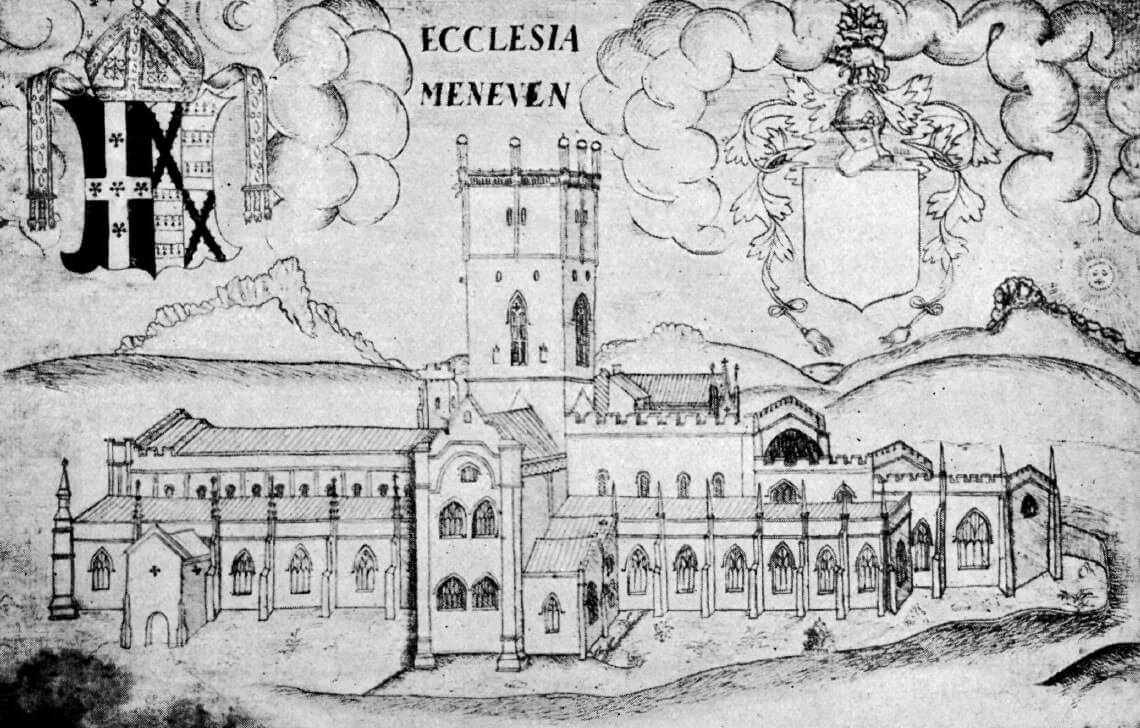

In 1171 St Davids was visited by king Henry II, who noticed the need to enlarge the cathedral. The construction of the new church began around 1180 – 1182, under the patronage of Peter de Leia, the Norman bishop of St Davids. At that time, a Romanesque nave was built, and in the next century a chancel, the transept and a tower at the crossing were added. Unfortunately, it collapsed already in 1220, and subsequent destruction was caused by the earthquake of 1247. The repair of the damaged cathedral was begun immediately and completed in the 50s of the 13th century. Over the next years, the chapel of St. Thomas Beckett and the Lady Chapel were added. In the first half of the fourteenth century, construction work was led by bishop Henry Gower. He raised the central nave and presbytery and transformed the lower windows in the style of late English Gothic. The tower was also raised by one storey. In 1365, bishop Adam Houghton and John of Gaunt began to build the College of St. Mary and the chantry. Later, a patio was added with cloisters, which connected the new buildings with the cathedral. During the episcopacy of Edward Vaughan in 1509-1522 a chapel of the Holy Trinity was erected, with a fan vault that perhaps inspired King’s College in Cambridge.

The first Protestant bishop of St Davids was William Barlow in 1536-1548. Trying to fight superstitions, he ordered to dismantle the sanctuary of St. David, confiscated the relics of the saint and tried unsuccessfully to transfer the seat of the bishopric to more Anglicized and less conservative Carmarthen. The cathedral remained at St Davis probably due to the attention of Henry VIII that his grandfather was buried there, though In 1550, bishop Farrer burned preserved medieval prayer books as the remains of the old order. During this period, however, not only destroying was preferred. The central nave was rebuilt, which roof of the Irish oak was placed in 1530-1540.

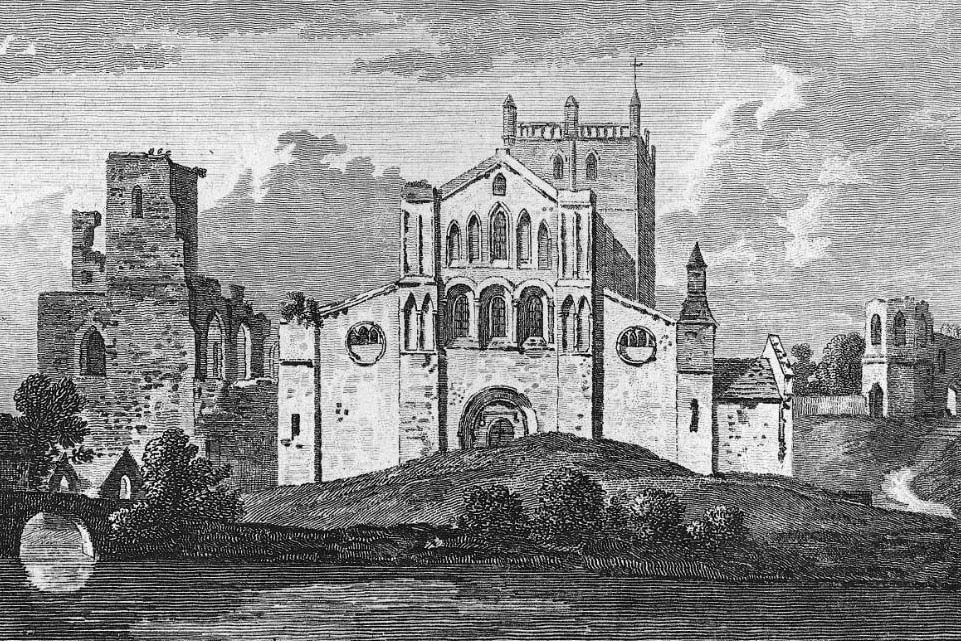

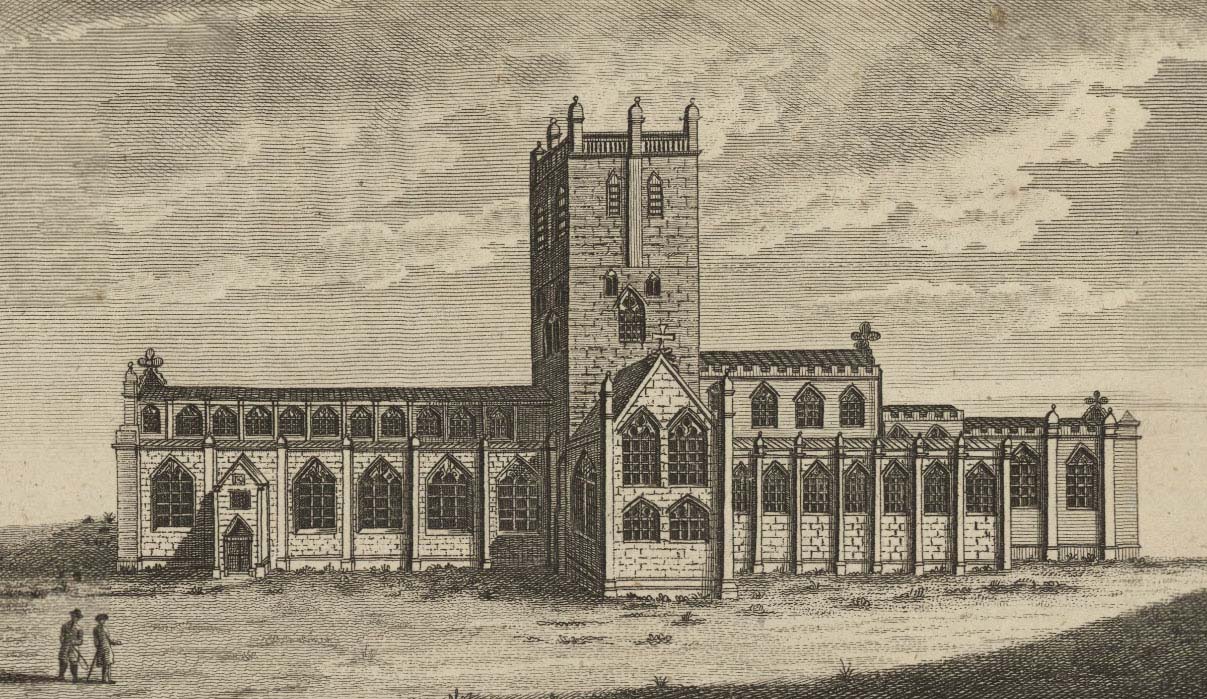

The establishment of a republic in the mid-seventeenth century influenced many cathedrals and churches in England. In 1648, the cathedral in St Davids was seriously damaged by soldiers sent by Parliament to obtain lead from its roofs. The organs and bells were destroyed at that time, and all the stained glass windows were smashed. The eastern end of the cathedral, devoid of lead, fell into disrepair and remained unroofed for over two centuries. The restoration of the cathedral was carried out between the eighteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1793, John Nash renewed the west façade, however, he blurred its Norman character and caused it to be unstable after only a few dozen years. In the early nineteenth century, William Butterfield renovated the windows in the aisles, installed a new window in the north wall of the transept, and in 1844 converted the south transept into a parish church. Due to the poor condition of the building, especially the tower in danger of collapsing, cathedral was renovated again by George Gilbert Scott in 1862-1878. Subsequent repair works, mainly at the chapels, were carried out at the beginning of the 20th century.

Architecture

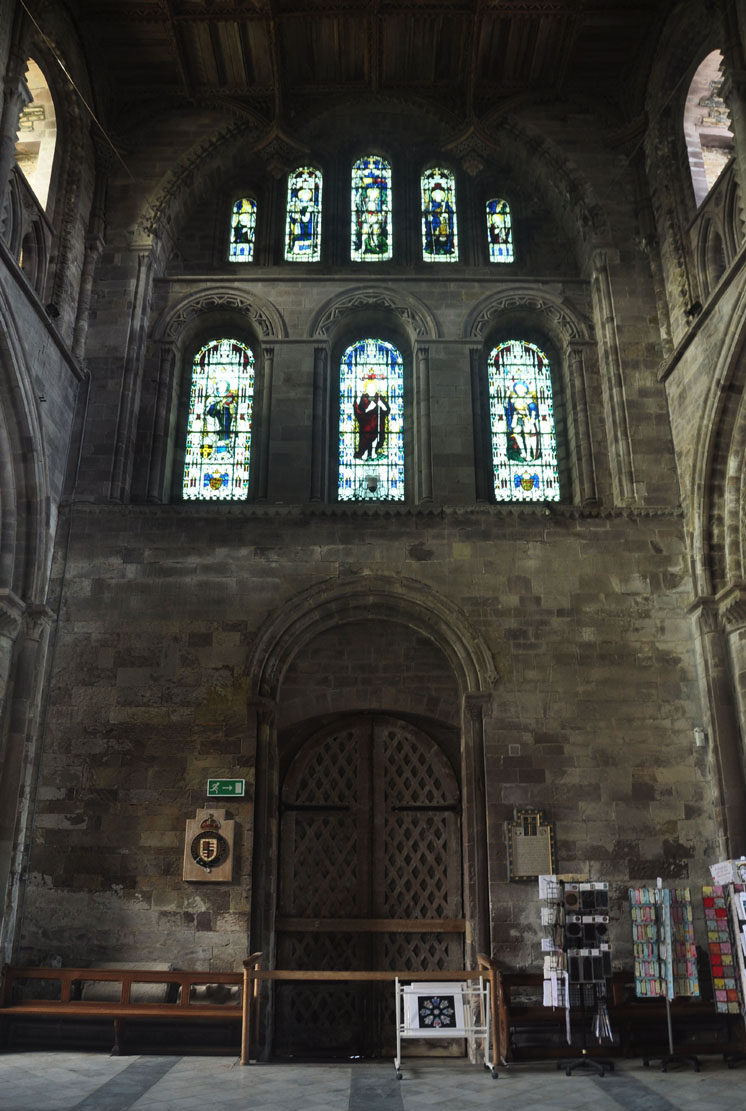

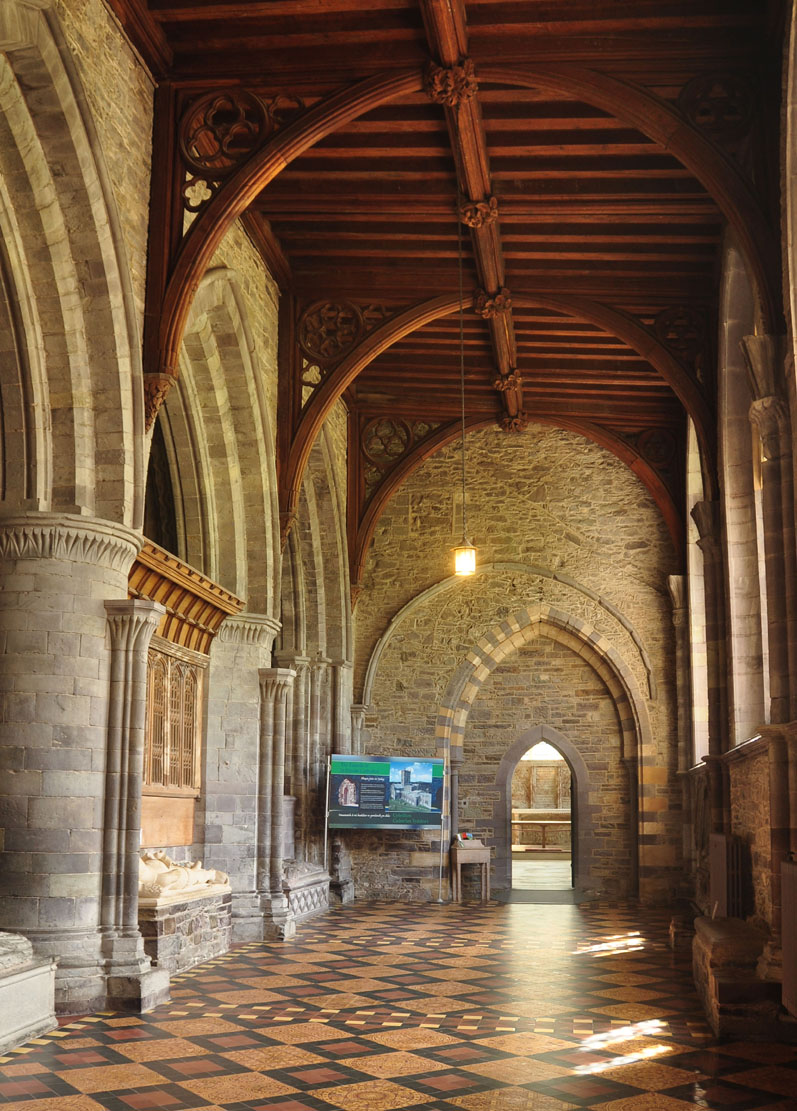

The earliest part of the Romanesque cathedral was the three-aisle, six-bay nave in the form of a basilica, erected in the fourth quarter of the 12th century. Due to the significant width of the central nave of about 10 meters, and at the same time a small height of 14 meters, it obtained a characteristic, flattened shape. Weak foundations and earthquakes that took place in the 13th century caused the wall on the west side to tilt, which resulted in the decision to cover the nave with a wooden ceiling instead of a stone vault. The difference in the height of the church floor was also characteristic, as the difference between its eastern and western parts was as much as 4 meters. It was caused by the foundation of the nave on the gravel of the old river bed. Probably due to the older buildings on the eastern side of the cathedral, the area was not leveled, but atypically, the difference was eliminated by gradually lengthening the inter-nave pillars on the west side, thanks to which the arcades could be constructed on the same level.

Despite the relatively low height, the interior of the nave received a three-level form. The lowest part consisted of semicircular, richly moulded and ornamented arcades, based on massive, alternating circular and polygonal pillars, moulded with semi-columns with capitals (three on each pillar from the side aisles, where they were to support the planned vaults, and single ones on each other cardinal side). Above there were ogival openings of the triforium made, arranged in pairs in high arcades opened to the windows of the clerestory. Two clerestory arcades came on one main inter-aisle arcade.

The interior of the nave was originally illuminated by not very large semicircular windows, in the first half of the 14th century, in the aisles, transformed into large, pointed windows with three-light, elaborate tracery. Their main building material was light purple sandstone from local quarries, while the traceries were made of yellow-cream stone. In order to accommodate larger Gothic windows, the initially low aisles were raised. The windows of the clerestory in the central nave, however, remained in their original, Romanesque form.

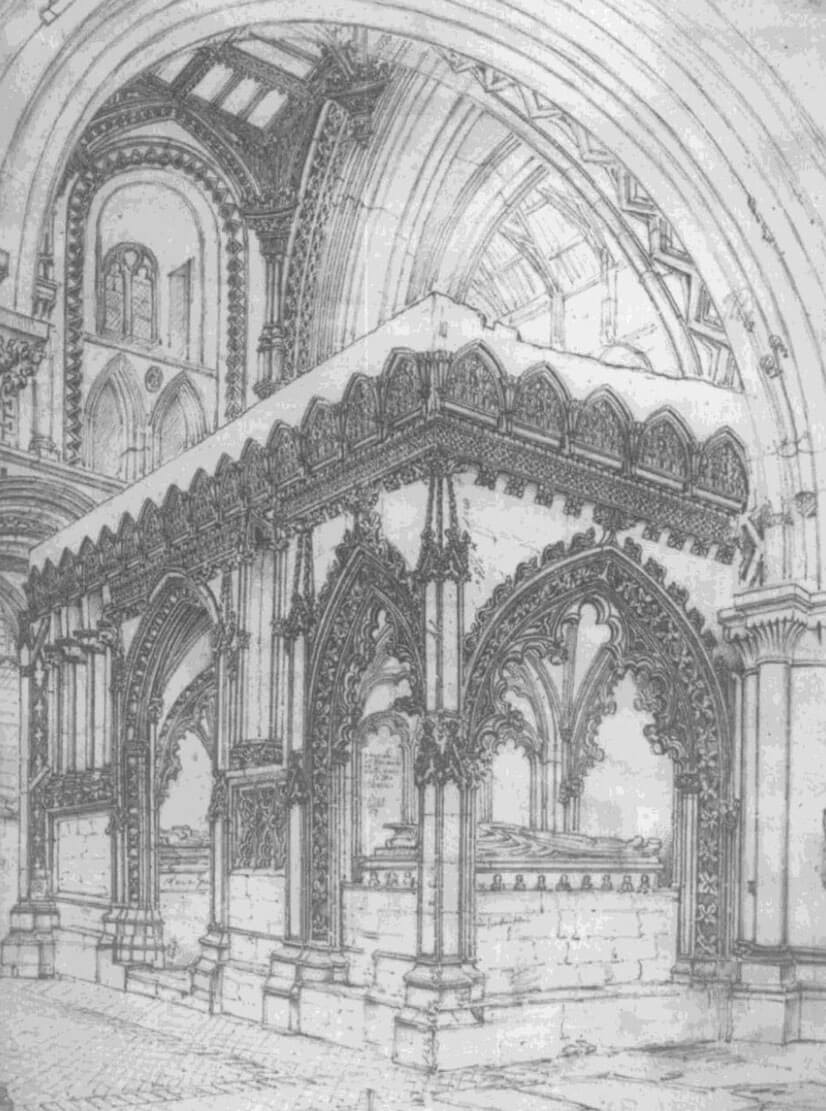

Before 1220, a transept and a rectangular three-aisle chancel were added to the nave. From the 14th century, the nave and the transept were separated by a huge, richly decorated, stone rood screen, incorporating to the tomb of Bishop Gower. It separated the western part intended for ordinary believers and the eastern, priestly part, behind which there were canons’ stalls. Its interior was so spacious that it was covered with a rib vault and covered with wall polychromes. The transept itself received quite a considerable length. It had three moulded arcades in the north and south of the eastern wall. The inner ones led to the side aisles of choir, the middle ones were blind, and the outer ones were connected with the side chapels. At the crossing a four-sided tower was placed, after a partial collapse in 1220, rebuilt in at least two phases. First, it was raised at the beginning of the fourteenth century by a part pierced with large pointed, two-light windows, and its upper part with a gallery and hexagonal pinnacles was added around 1500. As a result, the tower reached a height of 38 meters. The magnificent wooden ceiling of the tower, imitating a stone vault, was created in the years 1300-1325.

On the eastern side of the northern transept, at the beginning of the 13th century, a four-sided, although irregular in plan, chapel of St. Thomas Becket was built, perhaps placed on the site of the older, small church of St. Andrew, demolished after the erection of the transept. In the fourteenth century, it was thoroughly rebuilt by bishop Gower, but an early Gothic double piscina remained inside. Above the chapel, on the first floor, there was the cathedral library, the room of which originally served as a chapter house. The cathedral treasury was located on the second floor.

The original chancel had six bays, but they were much narrower than in the nave. Its arcades were placed alternately on round and octagonal pillars with shafts. In the southern part, in the clerestory part, a passage-gallery was placed, created after the side aisles vaults were abandoned. In the 14th century, as in the nave, the windows of the aisles of the chancel were also transformed in the spirit of the then fashionable Gothic style. At that time, their longitudinal walls were pierced with pointed openings with three-light tracery. Probably a bit earlier, at the end of the 13th century, a rectangular Lady Chapel was erected at the eastern wall of the chancel. Its construction was completed by bishop Martin, and in the fourteenth century, bishop Gower added sedilia and tombstones. Originally, the chapel was five or six-bay long, but in the 16th century, Bishop Vaughan rebuilt it into a two-bay. At that time, the walls were raised by about 3 meters and covered by a vault with a sophisticated system of moulded ribs, connected at the intersections with bosses in the shape of coats of arms. At the south-west corner of the Lady Chapel, there is a small chapel of St. Edward the Confessor, which is an extension of the southern aisle of the presbytery.

On the north side of the nave, in the fourteenth century, a square patio surrounded by cloisters, measuring 22 x 22 meters, was created. Originally, the west wing of the cloister consisted of two floors, while the eastern cloister was three-level. It was possible to get them to the building of the college chapel of St. Mary, who served the master and seven priests serving the cathedral.

In the years 1538-1539, the central nave was covered with a wooden ceiling made of Irish oak, unique for British cathedrals, consisting of a series of panels, two for one bay and six for the width of the central nave. In every second panel across the nave, there are openwork wooden arcades, filled with ornaments in the form of small trefoils, strengthening the structure. In the places where the arcades connect, there are richly decorated, hanging pendants.

Current state

Cathedral in St Davids is the most magnificent, most monumental medieval sacral monument in Wales. Its present appearance is the result of construction work carried out during most of the Middle Ages. The oldest walls from the end of the 12th century and the beginning of the 13th century have survived in the nave and transept, as well as in the central part of the chancel, while the eastern part of the church and the north chapel of St. Thomas are the effects of the Gothic expansion, which introduced a new decor also in the Romanesque part. The effect of the early modern reconstruction is the entire west facade, although it imitates the appearance of the facade visible in the oldest preserved iconographic sources. The chapel at the southern transept is also early modern. The most valuable elements of the cathedral include the ceiling of the central nave from the first half of the 16th century, Lady Chapel from the 13th / 14th century (rebuilt in the late Gothic style), it is also worth paying attention to the gate complex leading to the cathedral area.

bibliography:

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, VII County of Pembroke, London 1925.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.

Wyn E., St Davids Cathedral, Andover 2002.