History

According to tradition, the church in St Asaph was to be built as early as the sixth century, on the initiative of Saint Kentiger, the bishop of Strathclyde. His successor was to be a bishop, Saint Asaph, from whose the settlement took its name. The present church (nave) was founded in 1143 by the Normans, and about 1239 enlarged by an added chancel. In 1281, the relics of Saint Asaph were moved to the church, which were later the destination of numerous pilgrimages. Between 1284 and 1392, further extensive work was carried out on the development of the temple. During the term of bishop Llywelyn of Bromfield, at the beginning of the fourteenth century, the arcades between the aisles, the intersection of naves and the upper parts of the west façade, in which the new portal was added, were rebuilt. Walls of the aisles were partially rebuilt and new windows were added to the clerestorium. Between 1315 and 1320 a transept was probably erected and the tower was added in 1391-1392, erected under the supervision of master builder Robert Fagan of Chester.

The cathedral was destroyed several times, especially during the Welsh – English wars of the thirteenth century. In 1282, as a result of the support of the Welsh by the then Bishop Anian II, the church was ravaged by English troops. Further destructions took place during the rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr in 1402. The Redman bishop completed reconstruction only in 1482.

The English Civil War of the seventeenth century caused next damages. Perhaps because of them, the strained upper part of the tower collapsed in 1714 during a violent storm. In 1778, the chapter house was demolished and the chancel was rebuilt. Sir George Gilbert Scott carried out a thorough renovation of the building in 1867-1875, during which many changes from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were removed.

Architecture

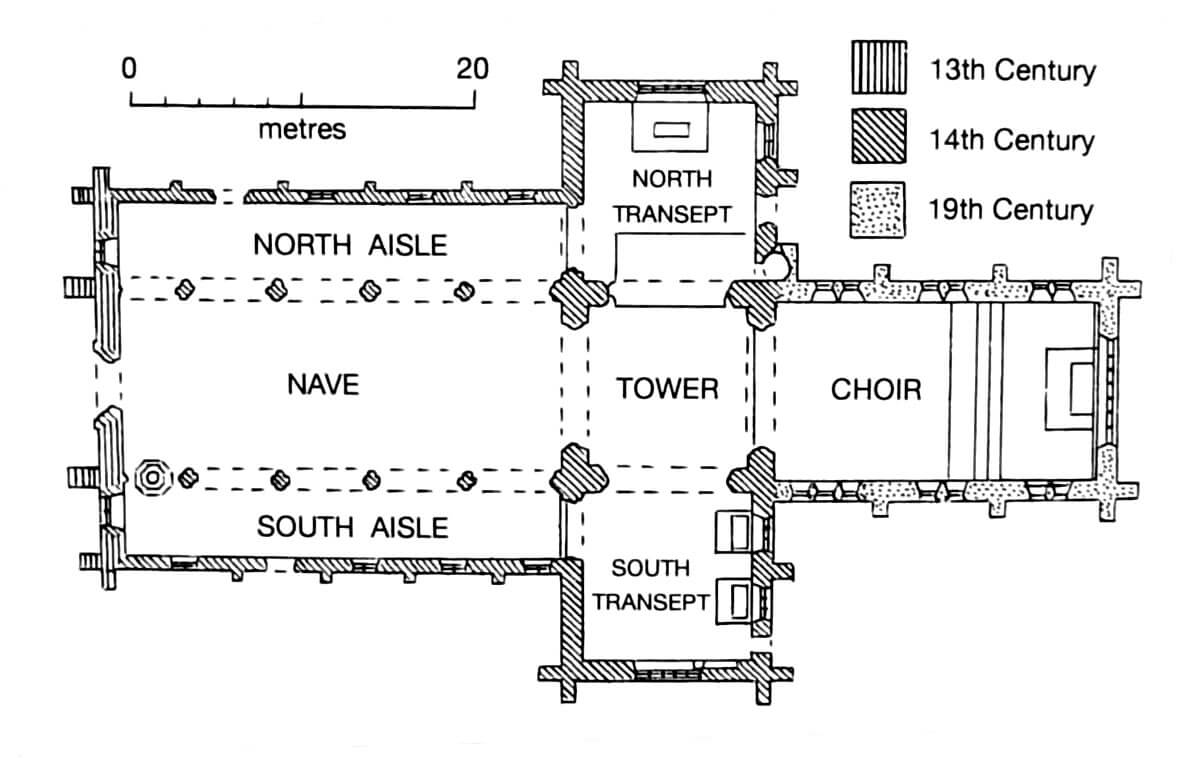

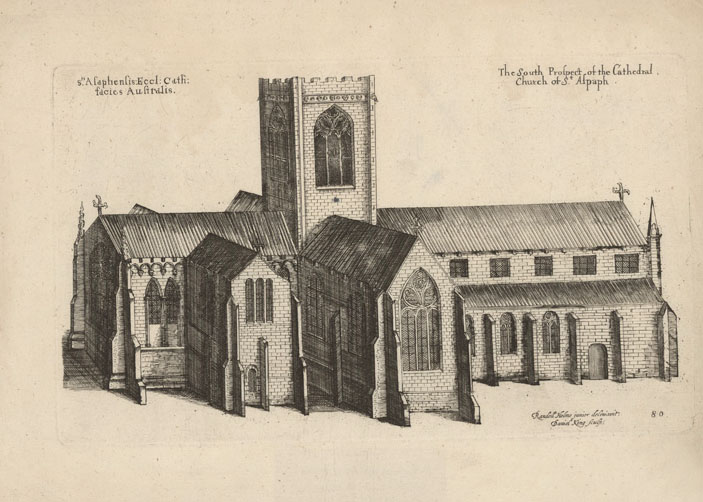

The cathedral was erected on a Latin cross plan. It received a three-aisle, five-bay nave in the form of a basilica, the northern and southern transept arms from 1315-1320, and a rectangular chancel on the eastern side. At the crossing in 1391, a four-sided tower was placed, while from the north, at the height of the central bay of the chancel, there was originally a two-story chapter house.

From the outside, the whole church was surrounded with buttresses, in the corners situated perpendicular to each other, especially massive and high at the west facade, stepped at the transept, chapter house and chancel. Between the buttresses, there were pointed windows. The largest, filled with multi-light tracery, were embedded in the western façade, the northern and southern walls of the transept, and traditionally in the eastern wall of the chancel. The top storey of the tower was also provided on each side with large windows, each with three-light tracery. The windows in the side walls of the chancel could have the form of narrower lancet openings, while the windows in the central nave had small, four-sided, moulded jambs, filled with unusual eight semicircles. The side aisles were illuminated by larger, two-light, pointed windows with archivolts topped with additional pointed shafts mounted on carved corbels.

The interior of the nave was topped with a wooden ceiling from the beginning of the 14th century, with timber ribs imitating the stellar vault. It were set on stone corbels carved in the image of human heads and figures, suspended just below the windows of the multi-foils clerestory windows. The aisles were separated in the nave with pointed, moulded arcades, based on pillars with a quatrefoil cross-section. The first bay from the west was much shorter, and the pillars did not corresponded to the location of the buttresses of the aisles.

Current state

The church has preserved its medieval layout to this day, although the chancel was thoroughly rebuilt in the 18th century and then regothisated in the 19th century (probably some of its lancet window openings repeat the original, medieval ones). The upper part of the tower had to be rebuilt, while no trace of the chapter house remained. Most of the nave windows were renovated, especially in the longitudinal walls of the aisles. The windows of the central nave, transept and west facade have retained their original elements.

Inside the nave you can see a beautiful wooden ceiling from the beginning of the 14th century, and in the presbytery there are unique stalls with canopy from the end of the 15th century, the only ones of the kind that have survived in Wales. They are tall, vaulted, decorated with pinnacles and carved decorations. William Morgan’s first translation of the Bible into Welsh is also stored in the cathedral.

bibliography:

Salter M., Abbeys, priories and cathedrals of Wales, Malvern 2012.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, II County of Flint, London 1912.

Wooding J., Yates N., A Guide to the churches and chapels of Wales, Cardiff 2011.

Website st-asaph.com, The Fourteenth Century.