History

Building of St. Brigid’s Church in Skenfrith began at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, during the reign of King John of England. It was consecrated in 1207. Probably in the early 14th century, the church was significantly enlarged by the addition of aisles and embellished with wall murals. At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries a porch was added, and in the following years a small sacristy. The building long escaped Victorian intervention, and only in 1896 did Edward Davies restore the roof trusses of the nave and chancel. Further repairs took place in 1909-1910.

Architecture

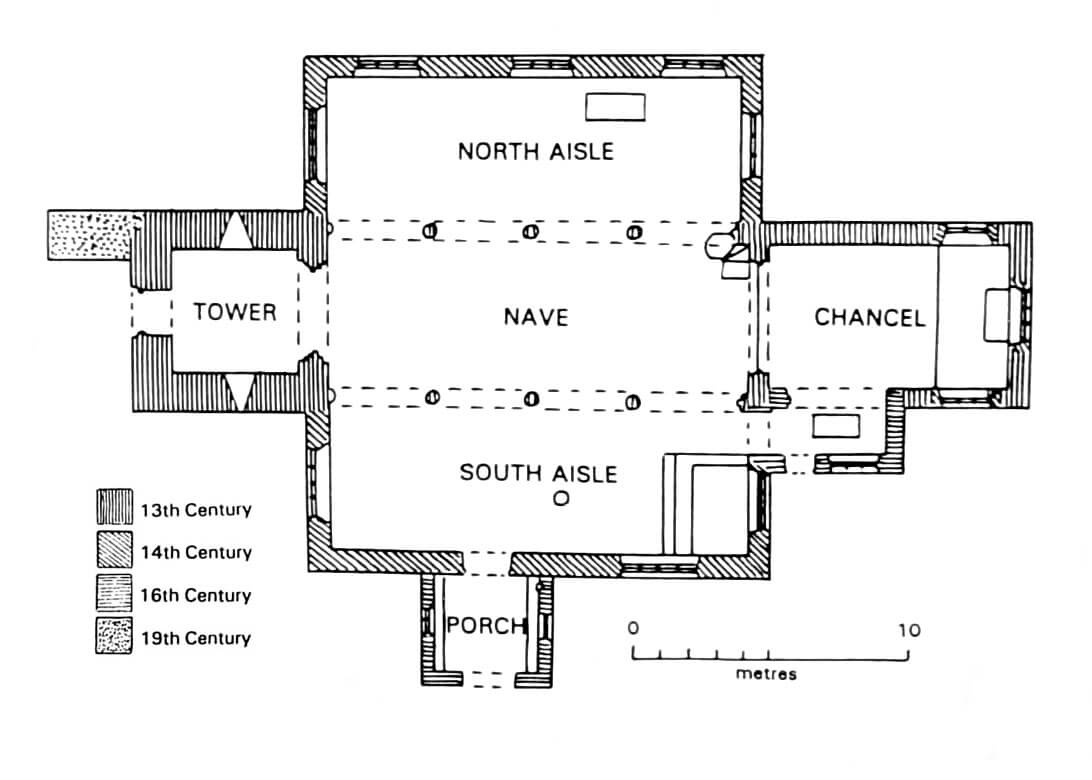

The church was built of red sandstone (Old Red Sandstone), slightly worked on the face and hewn into large squares to reinforce the corners. Initially, in the 13th century, it consisted of a rectangular nave and a similarly wide rectangular chancel. On the west side, a four-sided, squat tower was built, not very high, likely due to the unstable ground, because the church was situated in a valley near the western bank of the Monnow River, right next to a stream flowing into it from the north.

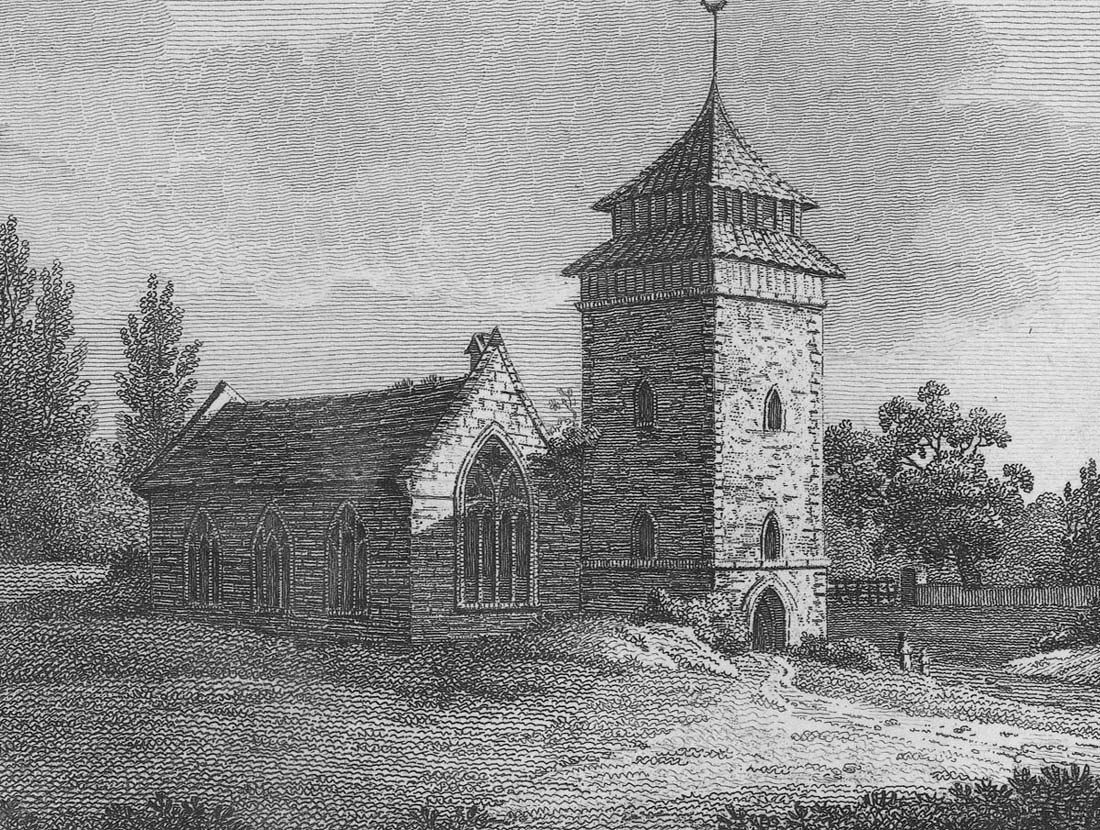

The tower was originally devoid of buttresses. Its walls were almost 1.5 meters thick, and the entire structure, pierced only by narrow, almost slit-like windows, gave the impression of having served a defensive function. On the ground floor, the tower walls were clasped with a massive plinth cornice. Another, somewhat more subtle string cornice ran just above the portal created in the western wall. The portal acquired a pointed, stepped form, with a pointed dripstone supported by two corbels. The tower was illuminated by the aforementioned small lancet windows, chamfered on the outside and splayed towards the inside. The tower’s crown may have initially been a battlemented parapet.

In the early 14th century, aisles were added to the nave on the north and south sides, equal in length and width. Each opened onto the nave with four arcades supported by circular pillars, and each was covered with a separate gable roof. The arcades were set on flat, moulded capitals (not all uniform) and decorated in the style common in the region at the time, with double chamfering on both sides separated by a groove. The chancel arcade was transformed during the Gothic reconstruction. Since than it has had a form similar to the nave arcades, but with polygonal jambs below moulded, minimally projecting capitals. The older, stepped arcade under the tower was crowned by a pointed archivolt supported by imposts.

Since the Gothic reconstruction, the church’s lighting has been provided by large pointed windows, mostly filled with simple but elegant three-light tracery. These divided the openings into three sections, with the center one formed by two vertical mullions and two side lancets created by smoothly extending short lateral shafts. Windows of this type were placed in the north elevation of the aisle, in the east wall of the chancel, and perhaps originally in the south elevation of the aisle. Further three-light windows illuminated the aisles from the east, where they may have been added somewhat later, as they were already equipped with ogee-arch tracery. On the west side the aisles featured more impressive four-light windows, with trefoil tracery inscribed in pointed arches. In the later Middle Ages, the windows on the church’s southern façade were replaced with late Gothic ones, with cinquefoil tracery set in quadrangular frames.

At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the entrance on the south side was preceded by a porch. Due to its large size, it was even equipped with two-light windows on the east and west sides. The entrance to the vestibule was located in a nearly semicircular portal, slightly angular in the archivolt due to the use of large voussoirs with simple moulding. In the later years of the 16th century, a small sacristy was added to the south wall of the chancel, lit by a large quadrangular window with semicircular tracery. The sacristy was built in such a way, that there was no need to remove the eastern window in the aisle or the southern window in the chancel.

Current state

The church luckily avoided major early modern transformations, thanks to which it remains one of the most interesting buildings in the Gwent region today. Only the tower had to be reinforced with a huge buttress, and it was topped with an unusual wooden dovecote. Almost all the windows have retained their medieval jambs and tracery, only the western one in the south aisle has been replaced. Inside, the church’s greatest treasure is a mantle or cape, which probably dates from the end of the 14th century. It is made of red velvet, with an embroidered image of the Virgin Mary and royal lilies. A thirteenth-century piscina and a baptismal font have also been preserved.

bibliography:

Newman J., The buildings of Wales, Gwent/Monmouthshire, London 2000.

Salter M., The old parish churches of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.