History

The first church in Rhuddlan was built no later than in the 11th century, as it was recorded in the Domesday Book in 1086, along with the settlement of “Roeland.” The settlement itself was first mentioned in records at the end of the 8th century, in connection with the defeat of the Welsh army by King Offa at the Battle of Morfa. It was next recorded in 921 under the name Cledmutha, reflecting the mouth of the River Clwyd. The name Ruthelan was used in 1191, Rothelan in 1253, and Rundlan a year later.

In the last quarter of the 13th century, King Edward I founded a castle in Rhuddlan, next to which he planned to locate a cathedral from the relocated episcopal seat at St Asaph. The intention to relocate the bishopric ultimately failed, so at the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, a more modest parish church was built on a new site in the newly founded town. The older church had likely been demolished by then to make way for the castle. In the second half of the 15th century, the early Gothic church was enlarged with a second nave, and around 1500, a tower was added to its western side. The expansion likely followed damages caused to the building in the early 15th century during Owain Glyndŵr’s Welsh rebellion.

Until the 19th-century renovations, the church underwent no major alterations. It was not until 1812 that construction work was carried out, unifying the appearance of the nave and chancel. The 14th-century section of the church then began to function as an aisle, while the 15th-century nave took over the functions of the nave and chancel. In 1820, Bodrhyddan’s mausoleum was added to the north side of the church, while a thorough Victorian renovation under the supervision of Sir Gilbert Scott took place between 1868 and 1870.

Architecture

The church from the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, was built on the high, steep banks of the River Clwyd, on the northwest side of Edward I’s castle, near the crossing connecting the chartered town with the route leading south to St Asaph. It was built as a rectangular, aisleless structure. The chancel was likely added somewhat later, but still in the 14th century, as suggested by the shape of the piscina in the south wall. Originally, it was slightly lower and narrower than the nave, covered by a separate gable roof, terminating in a straight wall to the east. The entire structure was situated within a rectangular cemetery, likely planned when the chartered town’s plot grid was created. It was likely surrounded by a stone wall in the Middle Ages, descending to the river level in the south.

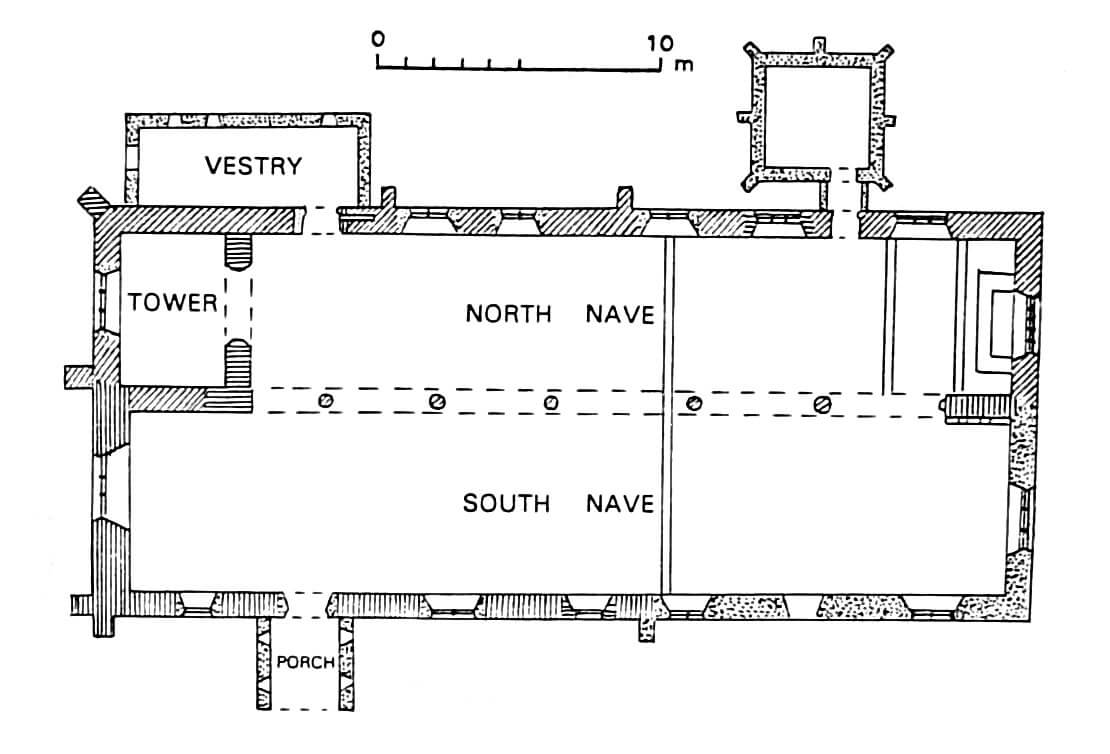

In the second half of the 15th century, a second nave in the English Perpendicular Gothic style was built on the north side, and then a quadrangular tower of the same width, with longer axis running north-south, was overbuilt over its western end. Both parts of the church, the older and the late Gothic ones, were of equal length, forming a strongly elongated rectangle, although the regularity of the layout was disrupted by the slightly narrower 14th-century chancel. The northern nave was covered with a separate gable roof, ended with a triangular gable similar to the chancel one. The spatial layout of the medieval church was complemented in the 15th century, by a small porch in front of the southern entrance to the nave.

The church’s exterior facades were reinforced with buttresses, arranged not at an angle at the corners, but perpendicular and parallel to the building’s axis. Only the northwestern corner of the tower was supported secondarily by a diagonal buttress. The buttresses were stepped and of low height. Only the western buttress was raised after the tower was added, creating a distinctive pilaster on the façade. The second characteristic element of the façade was a pyramidally arranged triad of lancet-shaped openings. Similar narrow and tall early Gothic windows may also have been located in the southern façade of the church and in the eastern wall of the chancel. Late Gothic windows of two-lights and three-lights were already placed in the walls of the northern nave, as well as the largest pointed-arch window with multi-light tracery in the eastern wall. The tower was lit on the top floor by pairs of small openings with trefoil heads.

Inside the church, the northern nave opened to the southern part of the building with six arcades supported by slender octagonal pillars. The three eastern arcades were created higher than the others, while the third, from the east was given an asymmetrical façade, likely due to the addition of a rood screen. In the Middle Ages, this rood screen divided the church space into a western section, accessible to all worshippers, and an eastern section, intended for priests. With the tower being placed in the western part of the northern nave, its ground floor was separated from the rest of the church by a wall with an arcade.

Current state

The church’s present form is significantly transformed since the 19th century, particularly in the 14th-century chancel, whose walls were unified with the south and north naves (the length of the original nave is now defined by the south buttress). Completely modern additions are the sacristy by the tower on the northwest side and the chapel (mausoleum) on the northeast side. On the south side is a 15th-century porch, which was also thoroughly rebuilt in the 19th century. Medieval architectural details have been largely replaced or renewed. Only the north wall of the nave retains late medieval windows from the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries and a relocated blocked portal, while the south wall contains a 14th-century piscina. A triad of lancet windows in the west wall of the nave and the large east window in the north nave may also be original. Inside, the arcades between the naves and several 13th/14th-century tombstones have been preserved.

bibliography:

Hubbard E., Clwyd (Denbighshire and Flintshire), Frome-London 1986.

Martin C.H., Silvester R.J., Watson S.E., Historic settlements in Denbighshire, Welshpool 2014.

Salter M., The old parish churches of North Wales, Malvern 1993.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, II County of Flint, London 1912.