History

Nevern Castle was founded at the Welsh settlement of Nanhyfer, captured in the early 12th century by the Robert FitzMartin, during the conquest of the Welsh cantref of Cemais, on the site of which an Anglo-Norman barony of the same name was established. Anglo-Norman control of Cemais had already collapsed in 1136, when the Welsh were victorious at the Battle of Crug Mawr. Nevern was probably recaptured by the Welsh, remaining in the hands of Prince Rhys ap Gruffydd from around 1156. Rhys was one of the most successful and powerful Welsh princes in the second half of the 12th century, which was reflected, among other things, in the reconstruction of Nevern Castle using stone.

In 1171-1172, Prince Rhys ap Gruffydd made an agreement with King Henry II, confirming his claim to the lands of Deheubarth, but with the obligation to return some of the lands he had taken to the Anglo-Norman lords. By this time, Robert FitzMartin had died, but his son William around 1176 had married Angharad, Rhys’ daughter, and the castle was probably returned to him at that time. Rhys maintained good relations with the Anglo-Normans until Henry II’s death in 1189. The prince then rebelled against Richard I and, taking advantage of his involvement in the preparations for the Crusade, attacked the lordships surrounding Welsh territory, breaking a series of oaths he had personally sworn on the most precious relics. In 1191, he captured his son-in-law’s castle, taking advantage of William FitzMartin’s absence, travelling to the Holy Land on a Crusade. The reasons for this action were not recorded. They may have been due to family problems, or they may have been caused by Rhys’s fears of the ongoing or planned expansion of the castle, which was very close to his seat in Cardigan.

In 1194 Rhys was imprisoned at Nevern Castle by his sons, following a bitter family dispute. He regained his freedom with the help of one of his descendants, Hywel Sais, who took the castle from his former ally and brother, Maelgwn. A year later Hywel Sais destroyed the castle to prevent it falling to the Anglo-Normans. The decision to abandon Nevern was almost certainly due to the loss of many men in an unsuccessful attempt to defend St Clear from the Anglo-Norman forces. The castle was never rebuilt, nor was it mentioned in records. Its function as the seat of the Barony of Cemais was taken over by a newer castle at Newport, following the occupation of the surrounding lands by the Anglo-Normans around 1204.

Architecture

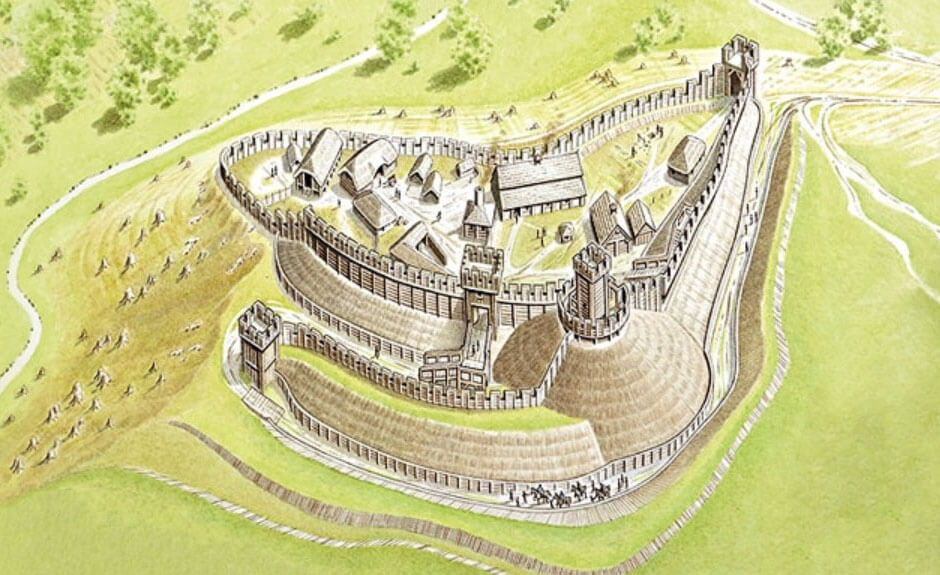

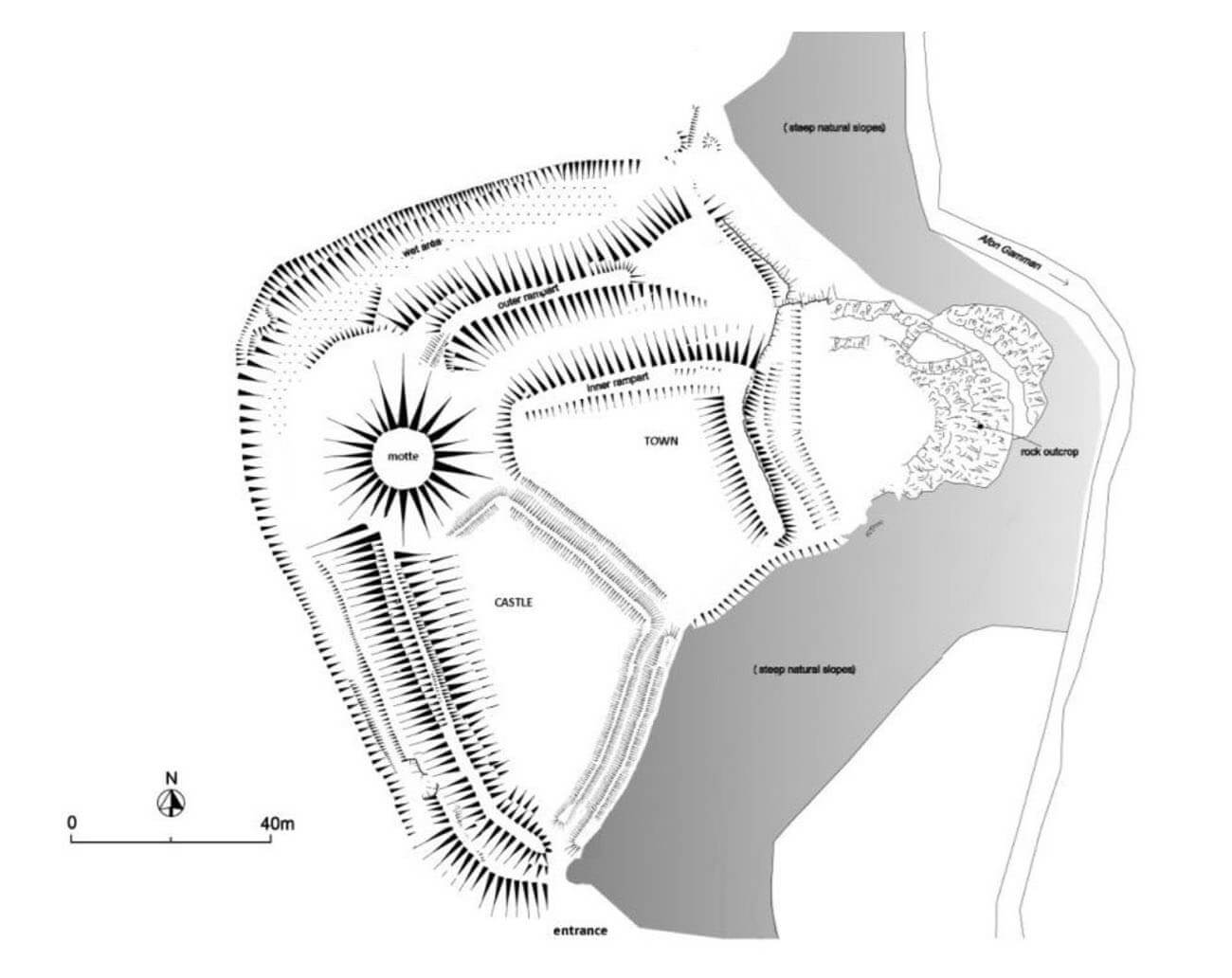

The castle was built on a hill, limited to the east by the valley of the Gamman stream, which flowed into the larger Nevern river to the south. For this reason, the highest slopes, creating a maximum difference in ground levels of about 30 meters, protected the building in the two above directions, with the east in the form of rocky cliffs and the south in the form of steep grassy slopes. The gentler approaches from the north and west had to be secured with earth fortifications in the form of a rampart and a ditch, doubled on the front north-west and north sections. The terrain conditions gave the castle a polygonal shape in plan, somewhat similar to a triangle.

At the beginning of the 12th century, in the north-west corner of the castle, an artificial mound (motte) about 8 meters high was built, on which a wooden tower was erected, with a structure based on four corner posts. It probably did not function as a keep due to its small size and exposed corner position, but was a watchtower and a structure securing the access road. The area to the south and east of the mound was occupied by a vast courtyard with wooden economic and residential buildings. The western and northern sides of the castle were secured by the above-mentioned earth fortifications, around which the road to the gate probably ran, forcing visitors to overcome three bends before reaching the castle. A solid wooden palisade was built at the top of the inner rampart. Wooden fortifications may also have crowned the northern outer rampart.

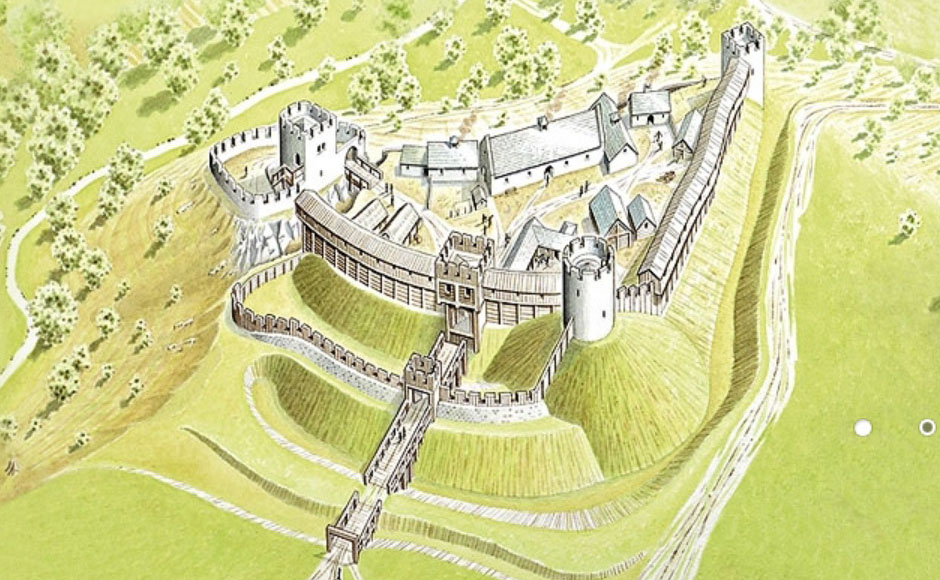

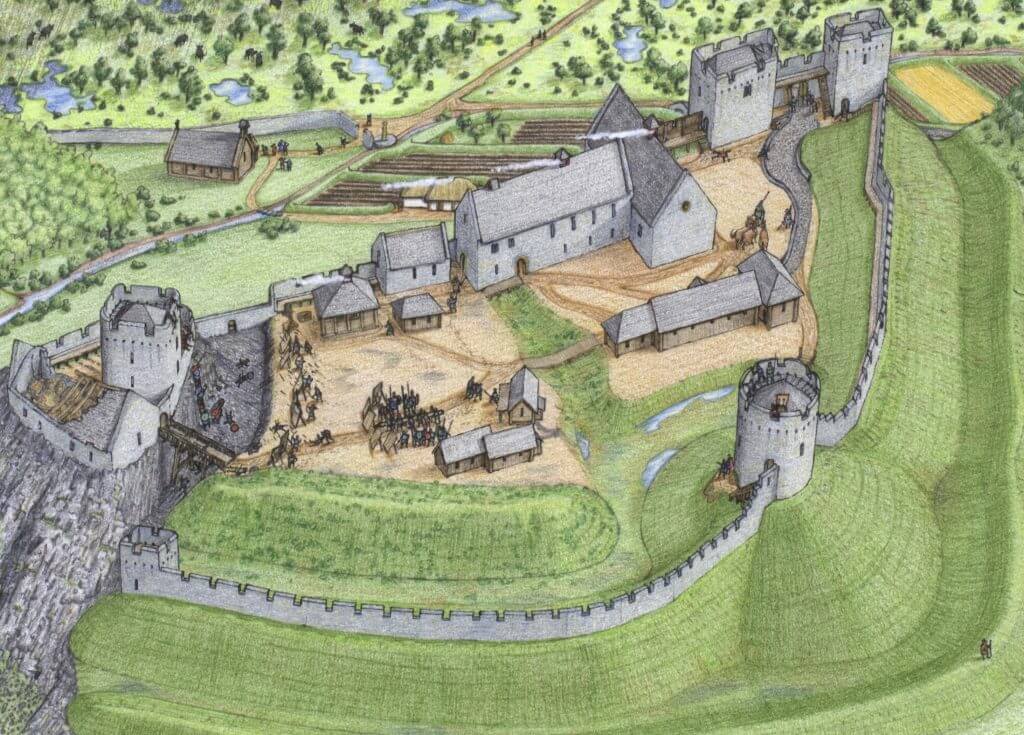

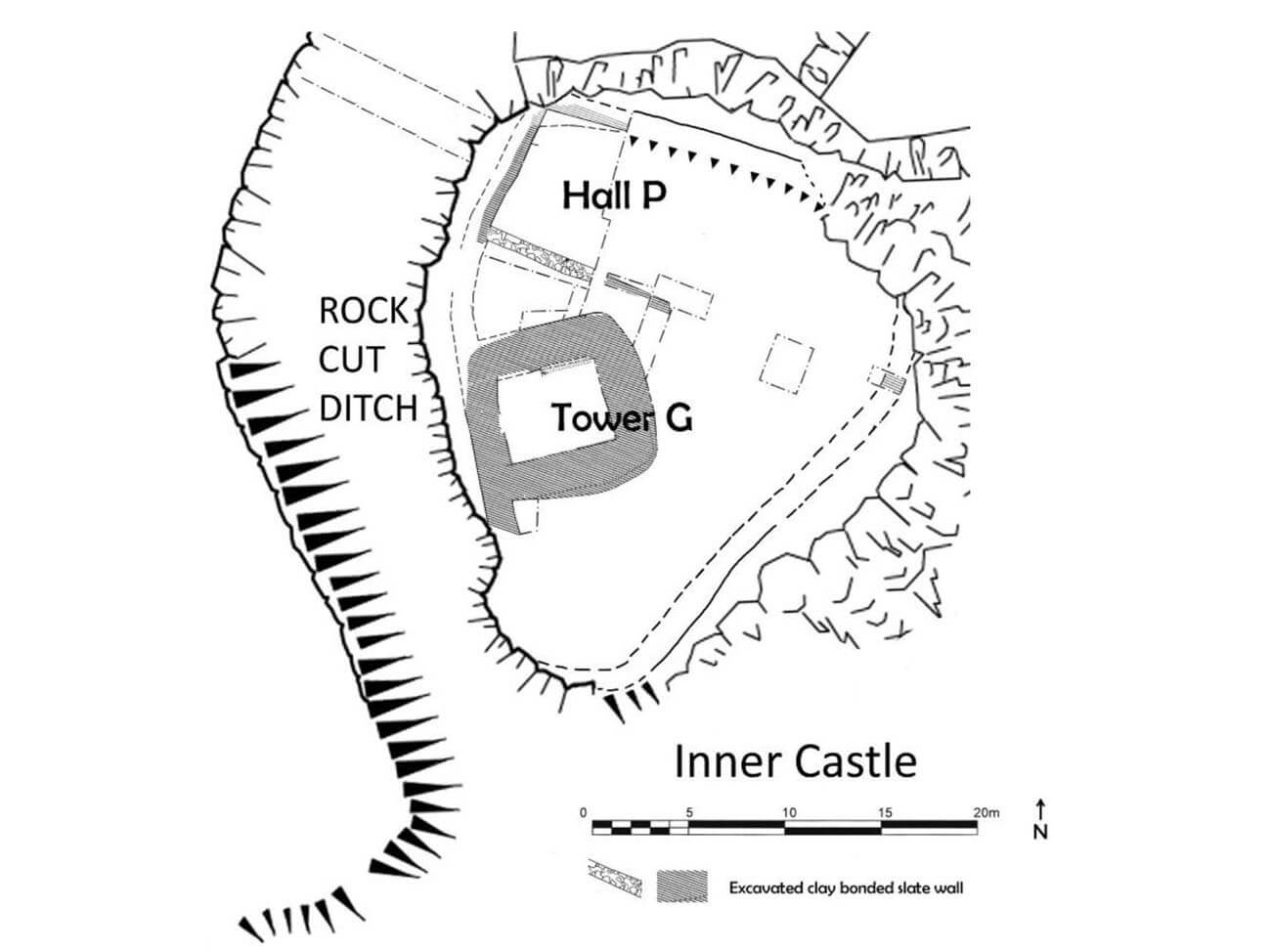

In the second half of the 12th century, Nevern was rebuilt using stone, specifically local slate bonded with mortar from clay. In the north-eastern part, an upper ward was created, separated from the rest of the complex by a ditch carved in the rock, about 8 meters wide and deep, over which a bridge was placed. The new part of the castle consisted of a circuit of walls separating a small, oval courtyard of about 25 x 20 meters and a quadrangular tower with sides about 9 meters long. The tower was characterized by rounded corners, which could have resulted from the use of clay mortar, a weaker binding than lime mortar, or the lack of suitably large stones to strengthen the corners.

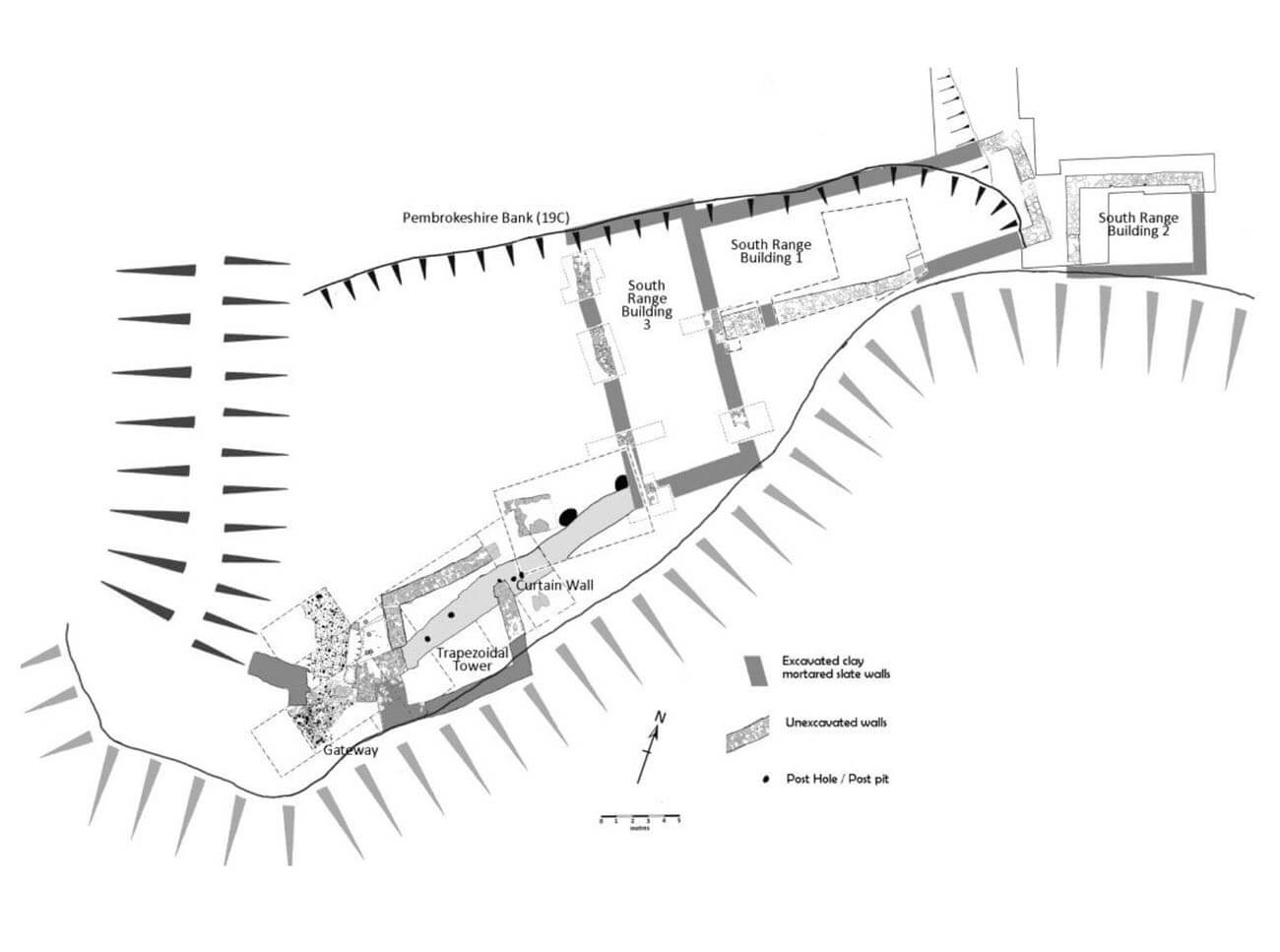

In the second half of the 12th century, the wooden tower on the north-west side was also rebuilt in stone. From then on, a cylindrical tower with a diameter of 9 meters rose at the top of the mound, the height of which was lowered to accommodate the stone structure. It had at least two or three storeys, with an entrance at the level of the second storey, accessible by means of a ladder or wooden stairs. The entrance to the extensive courtyard was still on the eastern side of the tower, and thus in the northern part of the castle, but it no longer had the form of multiple bends, but led straight north, through the wooden gatehouse and the external stone, timber and earth fortifications. The cylindrical tower dominated the entire gate complex due to its height and corner position.

At least three stone buildings were erected in the southern part of the courtyard, built of slate embedded in the clay substrate. The two largest buildings stood perpendicular to each other. The entrances to them were made of well-worked square blocks of hard sandstone. While the precisely hewn ashlars would suggest an Anglo-Norman masons, the technique of building with slate and clay was traditional in Wales. Another feature of Welsh architecture was the inclusion of buildings within the castle’s defensive perimeter. The two large wings could have housed a representative hall and its utility facilities, while the third one, slightly smaller and free-standing building to the east could have served residential purposes. On the western side of the buildings, in the corner of the courtyard, there was a second gate, with a road leading down a steep slope. The adjacent defensive wall was demolished at some point, and then a wooden palisade was built on the same line. It was probably a temporary solution, because soon afterwards a large trapezoidal structure, perhaps in the form of a tower, was erected on the site of the demolished curtain wall.

Current state

The castle did not survive to the present day. Only earthen ramparts and ditches, fragments of stone foundations and an earth mound (motte) are visible, subjected to intensive archaeological work in the 21st century. Among the stone relics, the remains of a cylindrical tower on a mound and a quadrangular tower with rounded corners stand out. The castle grounds are open to visitors. On its south-eastern side is the medieval church of St. Brynach.

bibliography:

Caple C., Nevern Castle 2008-2015; closing in on the first Welsh stone castle?, “Medieval Archaeology”, Vol. 60/2016.

Caple C., Nevern Castle: searching for the first masonry castle in Wales, “Medieval Archaeology”, Vol. 55/2011.

Davis P.R., Castles of the Welsh Princes, Talybont 2011.

Davis P.R., Towers of Defiance. The Castles & Fortifications of the Princes of Wales, Talybont 2021.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.

Turvey R., Nevern Castle: a new interpretation, “Journal of the Pembrokeshire Historical Society”, Vol. 3/1989.