History

The first castle in Neath was built in the 20s of the 12th century as a earth – timber defensive seat (ringwork). It was built by Richard de Glanville, knight of Robert, Earl of Gloucester and commander involved in the conquest of the Ogmore Valley. It owed its name to the Roman fort Nidum, founded in 75 AD. to protect the crossing of the Nedd River. When Richard founded Neath Abbey nearby around 1130, he abandoned the original castle, which was likely used by the monks as a source of building materials. The second castle at Neath was built on the opposite bank of the river, at the end of the second quarter of the 12th century, on the initiative of Robert, Earl of Gloucester, as the westernmost stronghold of the Lords of Glamorgan. It was first recorded in 1183, and its tower, probably of a wooden structure, was mentioned shortly thereafter.

With the death of Robert’s heir, Earl William, in 1183, a Welsh uprising broke out in Glamorgan, led by Lord of Afan, Morgan ap Caradog. The fighting concentrated around Neath, Kenfig and Newcastle, with Neath Castle under a long siege during which the Welshmen were to use siege engines. The blockade of the castle was removed by the relief of Ranulph de Glanville in the summer of 1184. Then William de Cogan, son of Miles de Cogan, was appointed constable of the castle. He brought six boats with supplies and weapons, and paid for a garrison of armed men under the command of William le Sor and Walter de Lageles. After the rebellion was suppressed, no major construction works were carried out in the castle, apart from the necessary repairs. In 1210, Neath was visited by King John on his way to Ireland, and he was also at the castle on his way back. The then constable of the stronghold, Falkes de Breaute, recorded expenses for repairs of the castle in the years 1207 – 1208, and next during the king’s visits.

A brief period of calm in relations between the Welsh and Anglo-Normans ended Earl Richard’s minority. Morgan Gam, Lord of Afan, released from captivity in 1229 after his capture the previous year, allied with Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, king of Gwynedd in North Wales, then in 1231 turned his attention to Castle Neath, which he destroyed in the same year. Once again, Neath was recorded in written sources in 1244, when the surrounding lands were invaded by the Welsh, but they were run away by the castle garrison. In 1246, the bailiff of Neath Castle was instructed in two statutes to ensure that the agreed terms were respected, under which the said Welshmen should compensate Margam Abbey for the damage suffered. Another invasion took place in 1258. This time the troops of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd were to ravage 150 houses in the town, but the castle managed to defend itself. It was probably already then rebuilt into a stone stronghold by Richard de Clare, the 6th Earl of Gloucester. He kept a constable in Neath along with a garrison of about 51 men (including a few servants) and 13 horses.

The Neath Castle managed to avoid Welsh attacks in 1287 and in 1294 – 1295, thanks to which at the time of the death of Earl Gilbert II de Clare in 1295 it was in good condition. At the time of his successor’s minority, the castle’s constable was Sir Peter de Stradling, and from 1297 Walter Hakelute. The death of Earl Gilbert III in 1314 in the war with the Scots caused another Welsh rebellion, but the castle did not fall into the hands of the attackers neither in 1314 nor in 1316 during the rebellion of Llywelyn Bren, although later repairs of the damaged roofs of buildings and towers were needed. The garrison of the castle ranged in this period from 20 to as many as 140 foot archers and several mounted armed men.

In 1321, the castle was captured and destroyed by Humphrey de Bohun, 4th Earl of Hereford, during a revolt against King Edward II and his hated favorite Hugh Despenser. Sir John Iweyn, Lord Loughor and Despenser’s Sheriff in Glamorgan, was captured then and after being transported to Swansea, he was beheaded by John de Tomeaux. The Despensers recaptured Glamorgan in 1322, and two years later Edward II issued a document at the castle in Neath, which would prove the removal of war damages. Probably, the castle was also rebuilt at that time of a new gate complex. In 1226, king and Hugh Despenser, while fleeing opposition took refuge in Neath a few days before being captured in Llantrisant. In Neath, Edward II likely left part of the royal treasury, which was later looted.

The castle was repaired in 1377, when it was under royal custody during the minority of Thomas Despenser. As a result, it was fully functional when the last great Welsh uprising led by Owain Glyndŵr reached its most critical phase in 1402-1404. Its garrison at that time consisted of one hundred archers and eight lancers. The following years, as for other Welsh strongholds, turned out to be calm for the castle, although in 1483 the castle constable Richard Willoughby was murdered. As he was walking from the castle to the church, murderer Thomas Gwyn attacked him on suspicion of having an affair with his wife. Probably in the 16th century, the castle began to decline due to the loss of its military significance, until it turned into a ruin in the 17th century at the latest.

Architecture

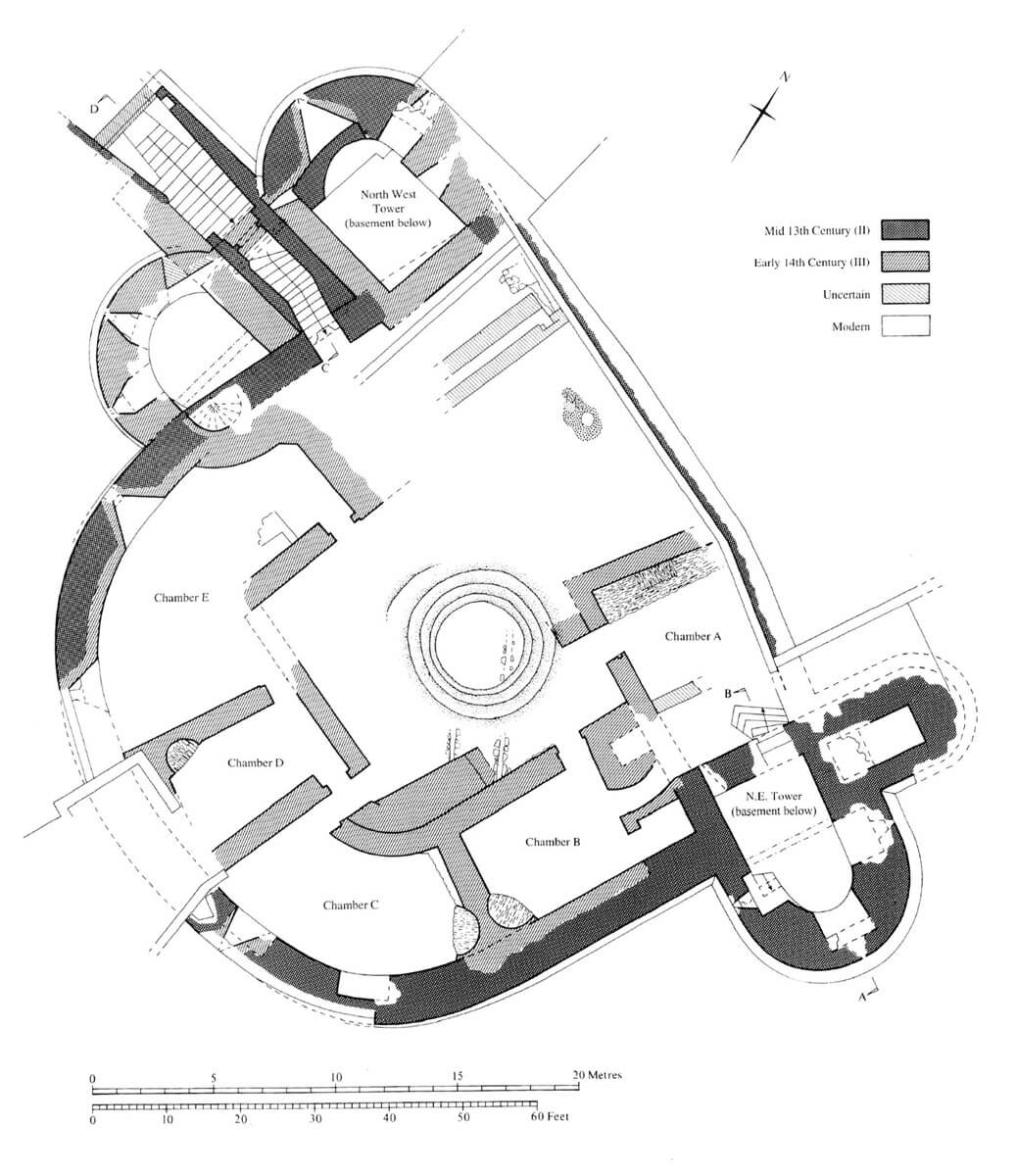

The castle was situated in a gentle bend of the river Neath, on its eastern, high bank, while in the Middle Ages the riverbed ran right at the foot of the slopes of the elevation. Originally, the castle consisted of a wood and earth perimeter of fortifications with a roughly oval plan, about 26 x 27 meters. It was therefore small compared to other early, nearby castles (eg Coity, Ogmore, or Rumney). It probably also had an outer bailey, located on the west or south side, opposite the settlement and the later town, where the descend of the area from the riverside elevation was the mildest. The outer bailey was protected by a ditch 6 meters wide and at least 4 meters deep, with a V-shaped cross-section.

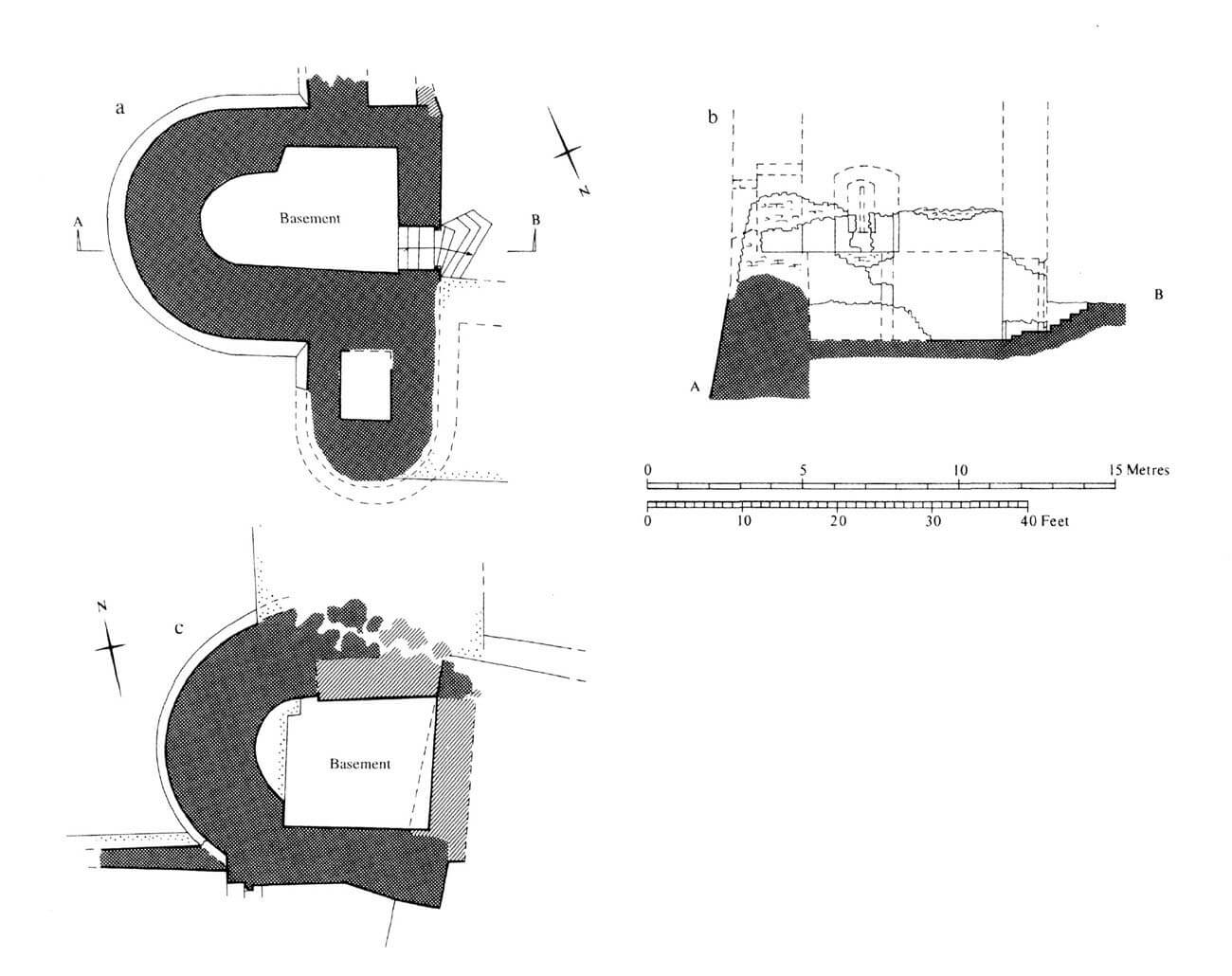

Before the mid-thirteenth century, the timber fortifications of the castle were replaced with a stone defensive wall, roughly repeating the outline of the older fortifications, resembling a horseshoe plan with a relatively straight north-east curtain and a rounded south-west part. Its defense was strengthened by two horseshoe towers, located on the north-west and east sides, at the corners of the straight section of the wall. The eastern tower, 7.5 meters wide and 10 meters long, additionally had a horseshoe-shaped, exceptionally large latrine turret, protruding north-east. The north-west tower protected the postern with a 6-meter long stairs descending towards the river. From the bricked up stairs, the side passage also led to the ditch, and from there to the outer bailey. However, the main gate was located in the southern part of the perimeter, facing the outer bailey and the town.

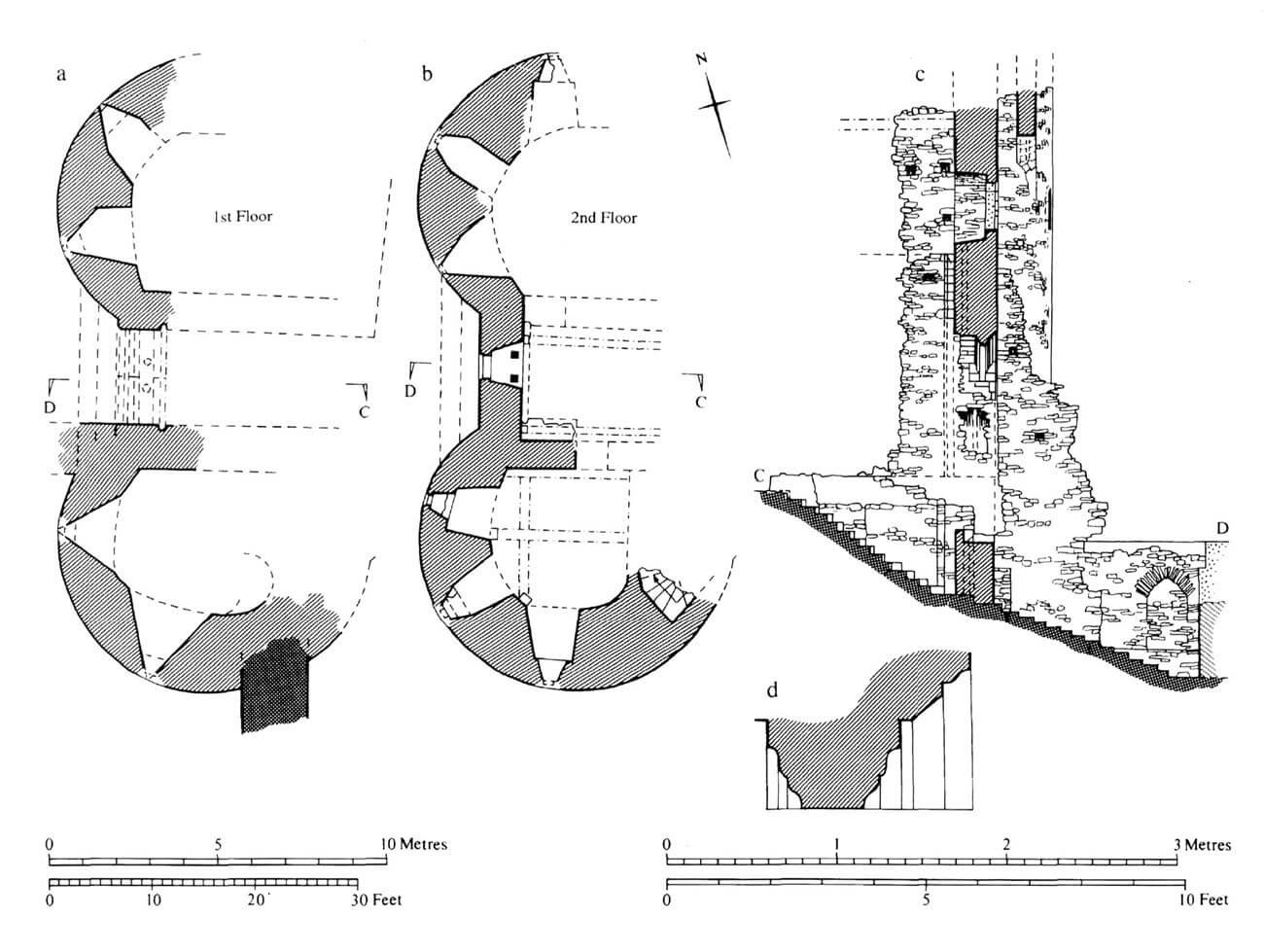

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, on the site of the north-west tower and postern, a massive gate complex was built, consisting of two towers flanking the middle passage (from the ground floor of the former tower, damaged during the fights, a northern gate tower was created, and the southern one was built from the foundations). Each of the towers was about 8 meters wide and 10 meters long. The gate passage after bricking up the old stairs was 2.8 meters wide. It was protected by machicolation stretched in the arcade between the towers, portcullis, doors, and loop holes pierced in the vault (so-called murder holes). Additionally, the passage was closed by a drawbridge over the pit. Both gate towers had three main floors, although the northern ground floor was founded on the buried lowest floor of the old tower. The interior of the ground floor of the southern tower was horseshoe-shaped and the northern one was quadrilateral, the northern one was additionally equipped with a latrine directed towards the ditch. On the first floor there was certainly a mechanism lifting the portcullis, while the second floor of the gatehouse could have a residential function, because, unlike the ground floor and the first floor, it was lit not by arrowslits, but by lancet windows. All of them were placed in segmental topped recesses.

The southern tower of the 14th-century gate complex was connected to the wall, which was probably part of the town fortifications. This wall was 4.6 meters high from the level of the gate passage to the level of the wall-walk. A further 1.7 meters high was the battlemented parapet of the town wall, protecting the wall-walk placed in the crown. The wall-walk was not connected to the gate complex by a portal, probably because of the desire to maintain greater independence of the castle and not to endanger it in the event of the town being captured by attackers.

The residential and economic buildings of the castle were erected in the courtyard next to the inner faces of the defensive walls. In the fourteenth century, it left a free space with only 11 meters long sides, and the wall was not blocked only at the northern curtain and at the gate. On the ground floor, the buildings housed five rooms, three of which were heated with fireplaces. It can be assumed that, in accordance with medieval customs, these lowest-lying chambers played an economic role (pantries, servants’ rooms, warehouses, etc.). Among them, the south-eastern room, connected by the corner with the eastern tower, served as a kitchen. It was equipped with a fireplace – a hearth and a oven next to which there was a passage of unknown purpose and a small pantry. From the adjoining room, nine steps led down to the dark basement of the east tower, well below the level of the courtyard. Only the upper storey of the tower was equipped with three radially arranged arrowslits, embedded in deep recesses in the thickness of the wall. The residential and representative chambers were probably on the upper floors, and the first floor of the western gatehouse,as mentioned, could also be used for this purpose. Additional economic buildings had to function in the outer bailey on the south side of the castle.

Current state

Currently, the best-preserved element of the castle is the outer part of the 14th-century gatehouse, reaching almost the original height, with the exception of the crenellated parapet. In addition, fragments of the defensive walls, relics of the eastern tower with a maximum height of 5 meters and foundations of internal buildings have been preserved. A unique discovery was the excavation of the stairs of the original postern from the 13th century, on the basis of which the 14th-century gate complex was built. The remains of the postern along with the stairs have survived to this day. Admission to the monument is free.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Lindsay E., The castles of Wales, London 1998.

Salter M., The castles of Gwent, Glamorgan & Gower, Malvern 2002.

The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, Glamorgan Later Castles, London 2000.